Understanding AdaptAbility

AdaptAbility Defined

Simply put, AdaptAbility is the ability to adjust to new conditions and situations. Every day, every person experiences changes that impact how we live our lives. Some changes we see as helping us, others we see as hindering us. As we grow and evolve, we realize that seeking AdaptAbility will engage, equip, and empower us to live better lives. Let’s understand AdaptAbility in more detail.

First, AdaptAbility is an Ability. It is a competency or capability that can be developed, grown, and mastered. By understanding how we experience change, we gain confidence and feel better equipped to handle life when new conditions or situations arise. By also understanding how others experience change, we are able to improve our relationships and help our teams and organizations more effectively plan and manage change.

Second, AdaptAbility is a Choice. As humans, we are hardwired for connection. We are also hardwired to initially resist change, especially when that change is the result of someone else’s choices. If we have insights into how we experience change, we can make better choices when shift happens.

In 1994, Desmond Tutu received the Nobel Prize for Peace for his role in the opposition to apartheid in South Africa. Amid national crisis and the dehumanization of his people, he said

“I cannot control what happens to me,

but I can control how I respond to it.”

AdaptAbility is not only a skill we can develop, it is also a conscious choice we can make in response to the changes that occur in our lives and workplaces.

Third, AdaptAbility is a Journey. There is no magic spell or miracle pill that can make a person suddenly handle change effectively. AdaptAbility starts with a willingness to learn and a desire to grow in our own skills and abilities.

If we do not take the time to understand our own experiences with change, it makes it difficult to show understanding, respect, and compassion for others as they experience change. AdaptAbility requires experiences for us to learn from, to journey through, and form the foundation we need to build our skill and competence.

As you read through this book, ask yourself the questions on the following page.

These questions start your journey. And as you move through this book, you are encouraged to not just understand the concepts, but to move beyond the information and apply it to your real life.

Who am I being?

Am I building the skill of AdaptAbility?

Am I choosing to respond to life instead of reacting to happenstance?

Am I effectively managing change, or am I being managed by change in my life?

Underlying Principles and Assumptions

Before we go any further, we need to clarify some underlying principles and assumptions that underpin the ideas, insights, and information presented in the remainder of this book.

AdaptAbility and Change Management

Throughout this book the terms AdaptAbility and Change Management will be frequently used. They are not synonyms. As defined earlier, AdaptAbility is a competency or skill that can be developed. Change Management refers to the processes, practices, and tools used to manage the people side of change to achieve the desired (business) results.

Simply put, Change Management

is a set of theories and tools

that are used to build the

competency and skill

of AdaptAbility.

In the book RelateAbility, the example of a QWERTY keyboard was used. We will use it again, but to describe the difference between AdaptAbility and Change Management. The example states that the keyboard is a fantastic invention and has many uses. However, if one does not learn to type, to build the competency or skill of using the tool, they will not be as effective as they could be. AdaptAbility is like typing, a skill that can be developed. Change Management is like the keyboard, a toolset we can learn to use to make our lives more effective at home and in the workplace.

Change has three primary causes.

Although change can happen in many different ways, there are only three primary causes of change in our lives.

- Crisis – Changes that are the result of crisis are immediately identified as having major impact on multiple areas of our lives, rather than limited to just one area. In most cases, a crisis-based change encompasses sub-changes that each will need to be worked through. For example, a divorce would be considered a change based on crisis as the impact of the change impacts finances, living location, parenting schedules, family relationships, and the personal impact of the termination of a critical relationship. Crisis-based changes are the most complex and often the most stressful of any type of change.

- Chance – Changes that are the result of chance are often seen as luck, fate, or random occurrences. For example, winning the lottery may have included the choice to purchase a ticket, but the change resulting from winning is purely based on chance. A forest fire that closes the freeway you use to get to and from work would also be seen as requiring change because of chance happenings.

- Choice – Changes that are the result of choice are the most common type of change we experience. Choice-based changes include choices we make for ourselves, like changing careers; or choices made by others, like being laid off from your job. Whether we are being impacted by others’ choices or choices we make ourselves, it is important to understand how we experience change and how to manage it most effectively.

When faced with new conditions or situations, it is helpful to be able to identify the primary cause of the change, not as a place of

blame or accountability,

but rather as a starting point to process the change in a purposeful way.

Change is neither “Good” nor “Bad”.

If we look to the guiding systems in our body, we realize that the brain is our central command. Neuroscience has studied the brain and how our central command experiences change – be it from crisis, chance, or choice. Our brain’s neuron network processes over two million bits of information every minute, yet we can only consciously hold five to nine thoughts at one time. This results in most of that information being unconsciously or subconsciously processed. As the brain’s neuron network is made up of electrical impulses, they are not registered as good or bad. As such, our body’s central command makes no differentiation or determination of whether change experience is good or bad for us, it is just information to be processed.

This is important for us to realize up front, because it gives us a better understanding why we will respond with the same levels of stress and emotions when dealing with a newborn baby not sleeping at night (which many would say is part of a “good” change) and the experience of losing a job and having to look for a new one (which many would say is part of a “bad” change). In a nutshell, change is what it is – a new condition or situation in which we can choose to either adapt or to resist.

Our experiences with change are predictable and sequential.

Research on personality and human behavior has shown that human beings are, for the most part, predictable in many of our behaviors.

Everyone needs to eat and sleep, we all have thoughts and feelings, and there are patterns in how we communicate and relate with others. Research on change has shown that human beings experience change in ways that are predictable and sequential.

Not only do we go through six stages of change, each with a specific set of feelings, thoughts, and behaviors, but also that we go through these stages in a predictable order.

Understanding that people handle change similarly, but also sequentially, will help us be more aware and mindful of our own stages of change as well as better support others going through change experiences.

There are some characteristics of change that are unpredictable.

Although experiences with change are predictable and sequential, this does not mean that everyone will respond identically. There are some characteristics of experiencing change that are not as predictable and may even be considered unpredictable.

Although everyone will go through the six stages of change, how we respond in each stage will be different based on the value we place on the change and the impact that change has on our well-being.

Even though we will each experience predictable types of thoughts, feelings, and behaviors in each stage, the intensity and duration of each person’s experience will be based upon the situation itself.

Some people will stay in a stage longer than others (duration) and some will experience the change with far more intensity. It is these characteristics, intensity and duration, that are most unpredictable.

So, one may ask, what basis do you make these assumptions about how people handle change?

Great question! The next section will go further in depth on the established psychological theory that we build our assumptions, beliefs, and competency development tools related to change management.

AdaptAbility and Established Psychological Theory

At the core of AdaptAbility is a model called the Change Curve. It is an applied model for better understanding the stages people go through when experiencing change. It is important that we understand the academic and scholarly research that has been conducted and that validates this model as we seek to build our AdaptAbility.

Change research has been conducted for decades. The earliest psychological model for change was introduced by Lewin in 1947 where he published a model that showed three stages of change – unfreezing, changing, and refreezing. In 1954, Maslow published his research known as the Hierarchy of Needs, providing insight to how people transition through predictable and sequential levels based on meeting specific motivational factors. McGregor’s Theory X and Theory Y were published in 1960 and shed light on the importance of attitudes and cognitive framing of new situations based on personal mindset. This early research, however, did not provide a practical and tactical model that could be applied in the practice of managing personal and organizational change.

In 1969, the Change Curve was introduced as a model that had far reaching effects on our understanding of change and the ability to effectively manage change. The Change Curve was developed by Elisabeth Kubler-Ross in papers published in 1969 and 1970 in the “Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine”. The initial model described the stages of grief and tracked the experiences we have in dealing with death and bereavement counseling, personal change, and trauma.

Between 1963 and 1971, Dr. Walter Menninger was conducting parallel research looking at how Peace Corps volunteers handled the change of being deployed to other countries. As a senior psychiatric consultant, he published the study in 1975 that presented a model that effectively mirrored Kubler-Ross’ Change Curve.

In 1976, “Transitions: Understanding and Managing Personal Change” was published by three British Researchers. Adams, Hays and Hobson analyzed how people were affected by different types of change. Their research showed similar reactions, behaviors, and experiences to the Change Curve research by Dr. Kubler-Ross and the findings of Dr. Menniger.

In 1980, Dr. William Bridges published “Transitions: Making Sense of Life’s Changes” and his research further supported the Change Curve. Additionally, his research went on to elaborate the methods of identifying which stage a person is experiencing and specific strategies for people in each stage to move forward most effectively.

In 1986, Dr. David Cooperrider of Case Western Reserve University published his doctoral dissertation entitled “Appreciative Inquiry: Toward a Methodology for Understanding and Enhancing Organizational Innovation.” In his research, he argued that the scientific base of positive psychology offers organizations an understanding of human growth and change that challenges the prevailing view of people as ‘resistant to change’.

In 1990, researchers Dottie Perlman and George Takacs conducted studies on personal reactions of nurses during organizational change in the healthcare industry. Their findings noted close alignment with the Change Curve and validated the application of Kubler-Ross’ and Menniger’s work to the organizational setting.

In 1990, Dr. Cooperrider published further details on the application of Appreciative Inquiry as it related to organizational change. In 1995, he published his “Introduction to Appreciative Inquiry” in the textbook Organization Development (5th ed), making Appreciative Inquiry an established methodology for using positive psychology in the management of change.

In 1998, Schneider and Goldwasser furthered the research relating to leadership and change management. They published the modern graphic of the Change Curve that is most widely used in current Change Management toolkits and training.

In 1999, researchers Elrod and Tippett from the University of Alabama conducted a series of studies to validate the initial “performance dip” by teams experiencing change in organizations. Their empirical study of the relationship between team performance and team maturity was published in the Engineering Management Journal.

In 2002, Elrod and Tippet published a comprehensive study entitled “The Death Valley of Change” in the Journal of Organizational Change Management. Their research concluded that the Change Curve was scientifically valid. Additionally, they found that 13 of 15 previous studies had also found valid evidence for all the elements of the Change Curve.

In 2004, Dr. Clark reviewed the research conducted on the neuropsychology of decision-making and the performance dip experienced during the process known as “reversal learning” or “unlearning”. Clark’s research published in the Journal of Brain and Cognition reinforced the importance of reorientation, developing new skills, ways of working, and relearning when experiencing change-related performance dips. Also in 2004, Losada and Heaphy offered further evidence of the benefits of positive psychology and appreciative inquiry, and particularly positive emotion, to organizational life. When people are being asked to do new things, or to work in an unfamiliar way, often working closely together, then these are exactly the resources they need to enable them to succeed in changing environments.

In 2005, Fredrickson and Branigan published empirical support for Appreciative Inquiry and of positive affect, demonstrating that positive emotional states are associated with more socially-oriented behavior, greater curiosity and exploration, and greater willingness to accommodate ambiguity or uncertainty.

In 2010, research was conducted on the application of the Change Curve on software technology change projects. Nikula, Jurvanen, Gotel, and Gause of Finland published their results in the Journal of Information and Software Technology concluding that change in IT change projects aligns with elements of the Change Curve.

In 2015, Leopold and Kaltenecker further enhanced the Change Curve in their research of change in culture and the impacts of change leadership in creating a culture of continuous improvement. Their work was published in the Journal of Organizational and Personal Change.

Overall there is an immense set of established psychological theory and research to support not only the predictable and sequential stages of change, the change curve, but also the value of incorporating positive psychology and appreciative inquiry in the toolsets of change management.

Multiple Points of View

Before we dive into the Change Curve, the Stages of Change, and Appreciative Inquiry, let’s talk about the POV – or Point of View.

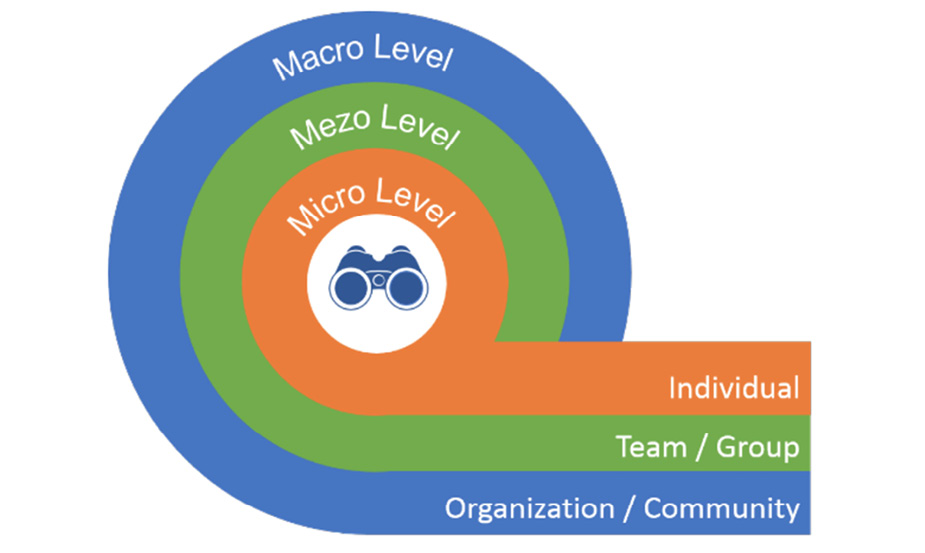

Change occurs on three levels and can be managed using the following three Points of View:

- Micro – This level refers to the level of individuals going through change. Here we will learn about how individuals think, feel, and how they behave when experiencing new conditions and situations. This is where we are able to better understand ourselves, and in doing so, better understand others. It is in this POV that we also realize that every team and every organization or community is really just the sum of the individuals within it. As such, we need to always keep this Micro point of view in mind as we seek to lead and manage change at any level. We will further explore this Point of View in Chapter 3: Personal AdaptAbility.

- Mesa – This level refers to the level of groups and teams. We will not dive into the individual definition of groups versus teams, other than to say that each are composed of two or more individuals working together. When these groups or teams experience change, they not only experience it as individuals (Micro POV) but also as a unit (Mesa POV). As we seek to lead and manage change, it is important that we understand how groups and teams experience development and change. We will further explore this Point of View in Chapter 4: Team AdaptAbility.

- Macro – This level refers to units consisting of smaller groups, organizations, and communities. In change management, this is often referred to as Organizational Change, although the practices used are not limited to just organizations. At this level, we must be aware that every Macro unit is made of groups/teams, and ultimately is the sum of the individuals that identify with that unit. There are specific practices unique to this level, but they must be integrated with the practices of the Micro/Individual and the Mesa/Team levels. We will further explore this Point of View in Chapter 5: Organizational AdaptAbility.

It is essential that we take into consideration each Point of View when implementing practices from the Change Management toolset.

For effective change to occur,

we must build AdaptAbility at each level: individually,

groups and teams,

and organizationally.