Chapter 7

When to Spend, When to Cut, and When to Scratch Your Head Over the Federal Budget

Putting together a budget may sound easy: you try to balance what you make with what you spend. Then, there is the U.S. budget.

The last time the fiscal affairs of the U.S. government were in the black was 2001. That makes some politicians see red, and they want to cut, cut, cut. Others see the budget as an opportunity to help provide jobs in their districts so the deficit isn't so bad.

In this chapter, we look at the importance of context in determining what to do about government spending. What is the state of the economy when the president sends his version of the budget to Congress? What are the dynamics needed to keep investors interested in buying U.S. Treasury bonds? And how does a government make significant changes if it won't touch entitlement spending such as Medicare, Medicaid, and Social Security?

Every year, government accountants, legislators, and their staffs and analysts pick through the budget, examining its nooks and crannies. But sometimes even the experts don't understand what's going on. As we will see in this chapter, a fog hangs over one of the most critical segments of the U.S. budget—the spending for health care, which represents about 25 percent of federal spending.

Impact of Health Care on the Budget

In the summer of 2013, the government needed Sherlock Holmes to help solve a mystery about one of the largest U.S. government expenses: health care. Something unusual was going on in the doctors' offices, clinics, and hospital wards. The rate of growth of expenditures was starting to slow for Medicare, Medicaid, and even private health plans.

The slowdown was significant. Health care expenditures came down from an annual growth rate of about 7 percent between the years 2000 and 2005 to 3.8 percent between 2007 and 2010.1 In 2012, the growth rate had declined to 3 percent, a rate that was last seen in the 1950s, when doctors made house calls and charged $4 for an office visit.2

Could the change be related to the economic downturn? Were people using less health care because they were out of work? Maybe seniors and others were taking fewer prescription drugs? Was there some obscure change in the federal repayment rates that was giving health care providers less money for their services? The people who study these things were perplexed.

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO), which produces independent analyses of budget and economic issues, put on its detective hat. Two CBO analysts looked at possible changes in Medicare's payment rates and the possibility that seniors were not going to the doctor as much.3 Perhaps seniors felt they couldn't afford health care because their stock portfolios had shrunk or their homes had declined in value.

What they found was a big question mark. Yes, they found that the recession cut into health care use but not substantially. They used complex economic formulae that looked at the data over a long period of time. But even after the economy started to recover and the stock market rose, the lower rate of growth continued.

At the same time, the CBO analysts looked more closely at individual seniors. “They looked at microeconomic data, households who had suffered larger wealth losses or other bad effects of the economic conditions, and those households did not seem to have any different reaction in their Medicare spending,” said Doug Elmendorf, the director of the CBO at a September 17, 2013, press briefing. “That leaves open the question: if it's not the financial crisis and recession, then what is it?” he asked.4

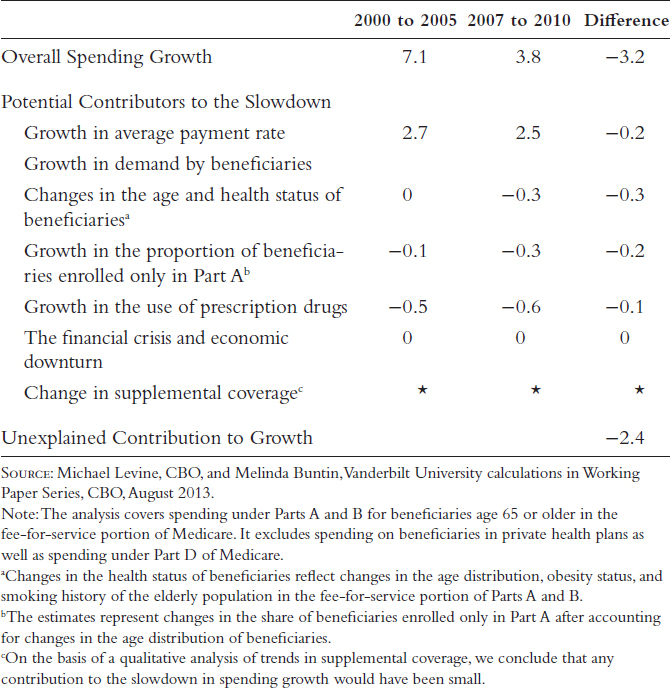

Table 7.1 shows the factors they looked at and the effect on the declining growth rate. At the end of the exercise, the CBO researchers could not account for 2.4 percentage points of the declining growth rate.

Other health care researchers tried to solve the mystery as well. On September 19, 2013, three health care experts, Amitabh Chandra of Harvard University and the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), Jonathan Holmes of Harvard University, and Jonathan Skinner of Dartmouth College and NBER, presented a paper at a Brookings Institution conference asking if the slowdown in health care spending was different from other periods when it slowed down only to soar again.

They agreed with the CBO that the recession itself was not the main reason. They wrote in the paper, “On theoretical grounds we question whether GDP growth itself should have a large impact on health care spending—short run income effects for health care spending are notoriously small (McClellan and Skinner, 2006), and it's not clear why Medicaid or retired Medicare enrollees should seek more (or less) health care when markets are in free-fall.”5 So they started with a hypothesis that only part of the reason for the slowdown was associated with the recession, and they turned to other possible reasons.

Some of the candidate factors included the possibility of patients faced with rising prices, a declining federal reimbursement rate to health care providers, cuts in Medicaid benefits, a reduction in technological advances, and a slowdown in the spread of older technologies.

Table 7.1 Contributions of Various Factors to Annual Growth in Per-Beneficiary Spending for the Elderly in Parts A and B of Medicare (percentage points)

They checked to see if stagnant wages for health care workers might be a factor or maybe people were holding off on going to the doctor in anticipation of Obamacare.

The Brookings analysis also put the drop in spending into the context of what was going on around the globe. Using an Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) report, they found that aggregate health care spending fell even more around the world between 2008 and 2011.

They wrote, “We hypothesize that this more dramatic drop in health care expenditures than in the United States reflects both the larger share of publicly financed non-entitlement spending in other OECD countries, and a sharper drop in GDP for many countries such as Greece and Ireland. . . .”6

The paper's authors also looked at the effect of technology, such as the widespread growth of hip and knee replacements and pharmaceutical advances in treating cancer. In the past, the increased usage of new technologies added to the cost of treating patients.

The Brookings authors wondered if there could be a slowdown in the spread of these leading-edge and expensive technologies. For example, in the 1990s, there was a large increase in the use of stents (tiny devices inserted into a heart's arteries to ensure blood flow). However, as the researchers noted, later trials in the mid-2000s suggested only modest health benefits for the most common types of heart diseases in the use of these procedures.

One new technology that could drive up the cost of health care in the future, they noted, is proton beam therapy, which its maker claims is more accurate for treating early signs of prostate cancer as well as other tumors near important organs. Treatment with the machines can cost as much as $50,000, or double conventional radiation, said the paper. The total number of these expensive machines was expected to double between 2010 and 2014.

However, even this technology was bumping into resistance. In the summer of 2013, Blue Shield of California told doctors in the state that there was no scientific evidence to justify spending tens of thousands of dollars more on the technology than for conventional radiation, and the big insurer said it would limit its payments to certain tumors in children.7

The three Brookings experts also asked whether the slowdown in the rate of health care spending might be temporary. They noted that in the early 1990s health care costs as a percent of gross domestic product (GDP) declined but then resumed growing at a faster rate in the late 1990s.

The CBO's Elmendorf wondered if the slowing growth rate might not last as well. “Previous periods of slower spending growth have been followed by a pick-up in growth again. And in those previous periods, some of the stories one heard, anecdotes, sound like some of the stories heard today. So I think we can't rule out that possibility” said Elmendorf.8

In addition, Elmendorf noted that costs could again start rising just because of the nature of the system. Medicare remains a fee-for-service system in which the incentive to provide more care is built in.

Perhaps because of doubts that the declining growth rate will continue, Elmendorf says CBO remains cautious in quantifying the impact on future expenses. Basically, no one really knows what is happening with health care costs and what the future trends will look like!

Doubts from a Doctor

While medical policy experts try to figure out what's going on with health care spending, pediatrician Dr. David Waters is on the front lines of health care at the 16th Street Community Health Clinic in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. From his perspective of treating children every day, he wonders how anyone could expect the growth rate of medical expenditures to keep slowing.

“I can clearly speak from the 26 years I have been at the clinic that the patient population that we care for is less healthy progressively over the time I have been here,” he says. And that decline in health in the young should be a red flag for the nation and its battle to control health care costs, he says.

In mid-September 2013 he had examined an 11-year-old girl who weighed 197 pounds, up from 169 pounds the year before. In 2012, he had referred the girl and her mother to a program at the clinic that promotes healthy choices for cooking and exercise. But the young girl still gained 28 pounds.

On another day in September, his first patient of the day was a girl who was almost 13 years old. She weighed 204 pounds. “A daily occurrence for me, I'm not even shocked by it anymore,” he said.

Well, not quite. On another day, he had a 14-year-old Latino boy who had ballooned 54 pounds to 256 pounds in 15 months. “Yikes,” he says.

These children are far from alone. He estimates that 40 percent of the pediatric patients at the clinic are overweight, and 25 to 30 percent are obese.

What's happening in that part of Milwaukee is true elsewhere but to a lesser extent. According to data compiled by the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey in 2008, 16.9 percent of all children ages 2 to 19 were obese. Boys were worse, with 19.3 percent obese, compared to 16.8 percent for girls. About 2 percent of children were in the category of extreme obesity.9

Overweight children are especially common in Latino commu-ni ties such as those served by the Milwaukee clinic. Nationally, 26.8 percent of Mexican-American boys and 17.4 percent of Mexican-American girls were obese between 2007 and 2008, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).10

“The obesity epidemic is disproportionately affecting minority communities,” says Dr. Waters, who estimates about 70 percent of the patients at the clinic are Latino. He thinks there are a number of reasons for the larger number of unhealthy people. For example, some urban areas are so-called food deserts, areas where there is a paucity of healthy grocery stores. In addition, he notes the Mexican population has a food culture that cooks with oils and makes fried foods. “And there is just a higher incidence of diabetes among Mexican-Americans,” he says.

Dr. Waters says people who use the clinic now expect their children to be fat. “One thing I have noticed just anecdotally is I get women who bring in their 15-year-old son to see me because they are being told by the family that he's too skinny. By comparison to everyone else in their community or school, they look too thin, so that's what people are sort of judging by,” he observes.

The children are not only having weight problems, but a rising number are developing diseases related to the excess weight such as type 2 diabetes, which used to be mostly an adult disease. “The prevalence of diabetes is creeping down into the pediatric population because people are getting obese at such a young age,” he says. “I think by early teenage years more and more people are going to end up with diabetes, insulin resistance. I know I see anecdotally more type 2 diabetes than I ever saw. The fact that it is in the pediatric population at all is a very scary thing.”

Once the children become adults, they have an even higher chance of becoming too heavy. Waters estimates that 77 percent of the adults the clinic sees are overweight or obese. This is higher than the national average, which is closer to 69 percent, according to the CDC.11

There will be future cost implications for so many overweight or obese people. The overly fat are more likely to end up with blocked arteries, which could result in a heart attack or a stroke, he says. “And those with diabetes may end up with kidney disease, eye disease, and vascular disease, and caring for those people is going to be a big expenditure for our country,” says Waters. “Obviously, the care that goes into that cardiac intervention with potential surgeries, coronary artery transplants, bypasses, and stuff like that is costly.”

Waters's clinic has not been just a passive observer of the obesity epidemic among their patients. In 2012, the health care facility held a “South Side Bicycle Day” in a nearby park. One hundred people came, and the clinic gave away 50 bicycle helmets, made up T-shirts, had bicycle mechanics to repair bikes, and provided salads and other healthy food. In 2013, 400 people showed up. The police donated 45 bikes that were auctioned off, and the clinic gave away 150 helmets.

“We had Zumba classes and we just had a really fun day,” recalls the doctor. “Next year (2014) we want to do it even bigger.”

If Waters and the clinic can start to change the mind-set and waist-line of his patients, he has plans. Waters, who rides his bicycle 7 miles to work every day, wants to give up his practice by 2017 and promote walking and bicycling in Latino communities across the nation.

Waters may have dreams, but he does not have illusions, which is one of the reasons he is skeptical about the slowing rate of growth on health care spending. To him, the key factor is the growing health problems of the country's population. “They seem to be considering people's health status as a static thing,” he says. “But it's not.”

What If Lower Health Care Spending Continues?

What does the falling spending growth rate mean? Despite lots of skepticism that the growth rate of health care expenditures will continue to shrink, there are huge implications if it does.

In 2013, the CBO decided to incorporate lower growth rates into its forecast for future health care spending.12 The nonpartisan agency reduced the estimate of how much Medicare and Medicaid will cost between 2010 and 2020 by about 11 percent compared to an earlier estimate in August 2010. By 2020, Medicare will cost $137 billion less than previously expected and Medicaid will cost $85 billion less. The total savings over the decade could be as much as $785 billion.13

There are two dynamics taking place that have an effect on this estimate, according to Elmendorf. First, the overall level of health care spending is coming down. A lower historical level reduces estimates of future costs.

“In fact, over the past three years, we have reduced federal spending for Medicare and Medicaid in 2020 by about 15 percent,” said Elmendorf. This downward revision matters even as much as 25 years down the road.14

“But in addition to the downward revision of the first 10 years, we have taken on more data in terms of the slowdown in health costs,” he explained. “Our estimate of the underlying rate of growth of health spending, which comes from a historical average, is lower than it was, so we have a lower level of health care spending to jump off from and a lower rate of growth beyond that. A combination of those factors is to reduce the federal health care spending by 0.6 percent of gross domestic product in 2038, which is a significant difference.”15

The slower rate of federal expenditures for senior health care, a program that affects 49.4 million Americans or about 15.1 percent of the population, could have significant ramifications if it were to continue for the next several years.16 The U.S. budget deficit could be lower. If the deficit were to fall, this could take some pressure off Congress to cut programs.

In part because of health care spending growing at a slower pace combined with the congressional mandated cuts through the sequestration process, the CBO expects the budget deficit to decline to 4 percent of GDP in 2013, down from 10.1 percent in 2009. The agency estimates that by 2015 it could be as low as 2.1 percent of GDP and remain below 3 percent for the following four years. That's all good news for those worried over the amount of red ink in the budget.17

But, as Elmendorf was quick to point out, it does not mean that spending on health care will be lower—just the rate of growth. Spending on health care in pure dollar terms will continue to rise, he says, for at least three reasons.

First, there will be a large number of Baby Boomers retiring and enrolling in Medicare. As a share of GDP, health care spending for the aging population accounts for 35 percent of the growth. The CBO estimates by 2023, about 60 percent of all health care spending will go toward people 65 or older.18

Second, there is the specter of a rising rate of health care per person. This is related to the possibility of advanced technology, such as new ways of fighting cancer or improved heart-related devices. The CBO estimates the fast growth per person segment represents about 40 percent of the growth of health care spending.19

Third, under the Affordable Care Act (ACA), also known as Obamacare, there will be an expansion of federal support for health insurance for low-income people, especially in the form of expanded Medicaid coverage and the creation of subsidies for insurance exchanges. This will represent about 26 percent of the growth, the CBO estimates.20

All these increases will mean that health care as a percentage of GDP will continue to climb. Between 1973 and 2012, health care was 2.7 percent of GDP; by 2013 it had grown to 4.6 percent; and the CBO expects that by 2038 the ratio will rise to 8 percent.21

The declining growth rate, even if it's only for a number of years, has its own implications. In an analysis in July 2013, Moody's Investors Service cited it as one of the reasons the rating agency decided to upgrade U.S. Treasury securities from a “negative outlook” to a “stable outlook.”22

But as of the fall of 2013, the mystery remained over the slower growth rate of health care.

How the Budget Interacts with the Economy

Any discussion about government spending needs to start with the basic idea that a budget is fundamentally a political document that has implications for both short-term and long-term economic growth. As we pointed out in the business sector, companies need to invest in order to increase output. Well, the same can be said for governments. The more that is invested in building the future economy, what economists call infrastructure, the greater potential future growth will be.

But the government doesn't just spend money on things such as roadways, schools, water, sewer, or electrical capacity. It doesn't just invest in health care research or support technology incubators. All of these are critical to building a bigger and better economy. What it also does is provide a variety of social programs.

When government does things such as fund unemployment insurance, food stamps, and welfare payments—to both individuals and corporations—pensions and other transfer payments from one group to another, it is spending money on concerns that are not necessarily considered to be investing in the future, as it is sustaining present economic activity.

The first question is: how should we, or even should we, balance the budget? It may surprise many, but the answer could just be: don't bother.

How you resolve the problem of revenues and expenditures being out of whack is not as simple as it may appear to the casual or even professional observer. The standard but way too simplistic view is that all you have to do is cut spending or raise taxes. While that may be the case initially, there are real economic impacts from any of those decisions that complicate the ultimate effectiveness of the actions. No matter what you do, some people gain while others lose.

Let's face it—the Congress and the president have not done a very good job in balancing the national budget. Indeed, the U.S. federal government has run budget deficits every year except for four during the past 40 years. The only time there were budget surpluses was during the fiscal years 1998 through 2001. (The U.S. fiscal year runs from October 1 through September 30.) For the rest of the time, revenues didn't come close to matching expenditures.

Looking at the size of the deficits, you see that they differ over time dramatically. It is hard to simply compare dollar values, as things such as the size of the economy, the size of the budget itself, and inflation all factor in. For example, in 1983, the government ran a $208 billion deficit. That was about 6 percent of the GDP at that time. In contrast, the $203 billion deficit in 1994 was only 2.9 percent of the entire economy, while the $248 billion deficit posted in 2006 was a mere 1.9 percent of all the goods and services produced.23 Clearly, it is not enough to simply say that the federal government is running a deficit. You have to put it into perspective.

And that raises the first issue that must be considered: should we ever run budget deficits, or should we always balance the budget or maybe even run surpluses? This is really the heart of the matter because there may be reasons to run deficits, or even more critically, deficits may be inevitable. Let's explain.

A budget is essentially a political document that has economic implications. The president presents a budget, and then the 535 members of Congress get together and in ways that are largely mysterious to even those in the know, pass a series of bills that ultimately create the means to spend a huge amount of our money and collect usually less than that total.

Of course, the passage of all the budget bills is just the beginning of the spending process. Emergencies occur during the year, so there are special spending bills. And the economy matters as well. If there is a recession, a lot of workers wind up on the unemployment and welfare rolls, so spending can surge. In good times, people find jobs and stop receiving government payments, so spending might even be less than expected. Sometimes war breaks out, and that raises spending. So the budget is just the first attempt at describing what the government will spend. What it actually does is determined by the course of events during the year.

And then there are taxes. In times of economic troubles, taxes may be cut after the budget is passed so that people can keep more of their hard-earned income and hopefully spend it. But that reduces government revenues, at least in the first few years after a tax cut occurs. However, if the deficit is getting out of hand or the politicians want more spending, they sometimes raise taxes to increase revenues.

That the budget passed is just a guide to spending and taxation may be troubling, but it also points out that coming up with a balanced budget is no easy task. Indeed, it is likely to be impossible since there are so many moving parts during the year. The reality is that only by accident will spending and revenues wind up at the end of the fiscal year to be in balance.

Let's skip the idea that we should have a balanced budget and instead ask: why should we ever run a deficit? The answer is actually straightforward: you want to run a deficit when the economy needs to be kick-started.

A classic example of when lots of additional government spending made sense occurred in the spring of 2009. The financial markets had crashed in the fall of 2008, and the economy was rapidly following suit. With consumers fearing a depression and spending disappearing, corporations were facing an economic meltdown. Instead of looking to grow, firms assumed the turtle position and hunkered down. They adopted a simply strategy: survive until the end of the year. Hiring turned into firing, and payrolls were being reduced by 700,000 a month.24 Near panic was taking hold.

Under those circumstances, the major worry was how to stop the free-fall before it snowballed into another Great Depression. Obviously, with the economy spiraling downward, neither businesses nor households were going to go out and spend money. Thus, the burden fell entirely on the government.

If the economy was going to break its fall, either it had to hit rock bottom or the government had to become the spender of last resort. Would tax cuts help? Not really. Since people and businesses were looking to hoard money, most tax cuts went into savings. Though about 30 percent of the stimulus bill that was passed was for tax cuts, at least during the first half of 2009, little was turned into spending on the part of households or companies. Therefore, the government had to spend money.

The federal government was the only economic actor who had the ability to spend more money even if they didn't have the revenue coming in. All it had to do was borrow it from people either in the United States or around the world. And that is precisely what happened.

Did the stimulus, as it was called, make a difference? That will be debated for years to come, but the massive collapse in the economy came to a halt in June 1999.25 Did that happen by magic? Did Harry Potter wave his wand and the recession ended? I seriously don't think that was the case. The huge inflow of government funds into the economy had to play a role in turning things around.

When it comes to the budget, whether the government spends more money itself or reduces taxes and lets businesses and consumers shop till they drop, the deficit is going to rise. Tax cuts reduce revenues in the short term since it takes time for the funds to be spent and growth to accelerate that ultimately causes some of those tax losses to disappear.

However, government expenditures directly add to the deficit. That is true whether new projects are being funded or there are greater demands for safety-net programs. When the Great Recession hit, all those people who were out of work, as well as all the members of their families, were in need of support, and that meant even more spending on social programs and unemployment compensation. In times of major trouble, the only course of action, if action is to be taken, is for the government to run a deficit.

If deficits get run during bad times, when should the government actually start paying down the debt by accumulating surpluses? That, too, is fairly straightforward: when the economy is running full out. During boom times, revenues are rising sharply, and as long as spending is kept under control, government revenues might actually exceed outlays. That happened at the end of the 1990s when strong growth and a surging stock market created rivers of revenues for the government. Huge surpluses followed that actually could have continued if events and politics had not intervened.

Alas, anyone who understood Washington, D.C., knew that budget surpluses would never last, and they didn't. But at least for a few years, the nation's debt load was being paid down a little. The point is that it is good to run surpluses when the economy is strong, and if some money is taken out of spending and put into debt reduction, the economy can handle it.

The lesson is that there is nothing special about a budget deficit or surplus. Whether a deficit or a surplus is run depends on where we are in the business cycle and how the government reacts. It is all about context and the condition of the economy, income growth, and gains in equity. All those combine to create a revenue flow that may or may not balance out with the wants and needs specified in the spending portion of the budget.

It is economic reality that causes the government to run deficits or surpluses, and no policy can possibly stop that. Indeed, a balanced budget requirement would exacerbate problems. We have seen that a spiral into recession, which causes income and tax revenues to fall quickly, will create a deficit. If there were a balanced budget requirement, either taxes would have to be raised or spending cut. That would result in the economy's faltering even more, further depressing revenues. A never-ending negative cycle of higher taxes, lower spending, and slower growth would be initiated.

The only way out of the crises that would be caused by a balance budget amendment would be for the requirement to be flexible. When the economy was faltering, a deficit would be allowed. But by how much? If it is not enough, and few would have expected the huge decline that occurred after the financial sector's near collapse, then the negative cycle would be set off.

Even if politicians wanted to, spending could not be cut quickly and the social safety net would ensure that spending would jump. If you are unemployed, you get unemployment insurance. It is not easy or frequently not possible to control costs when the economy cycles downward. You can try, but it is doubtful you will succeed.

Similarly, long periods of strong growth generate rising household spending and income, which leads to improving corporate profits and stock values. Ultimately, that creates much stronger flows of revenues into government coffers, and surpluses become possible.

In good times, it might make sense to either spend more or tax less. But we already know how that ends. In the spring of 2001, when we had already benefitted from a string of surpluses, Congress decided to cut taxes. At the time, the forecasts were for budget surpluses in the $650 billion range for years to come. Within a few years, we were running $650 billion deficits. So much for managing the budget when the coffers are flush.

When asked the question, “Are deficits or surpluses good or bad,” the answer will be: it depends on the condition of the economy.”

It's Not the Deficit but the Interest That Matters

When you run a surplus only four times in 40 years, you can basically conclude that Congress and the president are not too worried about deficits. It is a lot easier to simply spend more than you take in and borrow to make up the shortfall.

Should we be worried about deficits? The answer is, of course, it depends. First, understand the difference between a deficit and the national debt. The deficit is the annual shortfall between revenue and expenditures. For example, in the fiscal year that ended September 2013, the government ran a deficit of about $680 billion.26

Now $600 billion is a lot of money, to say the least. But that was the shortfall that was run in just one 12-month period. To get the national debt, you have to add that to the deficits that have been run since we became a nation. At the end of 2013, that had reached $16.5 trillion. And that is an extraordinarily large number.

Indeed, if you think that we can pay off that debt, forget about it. The debt is about the same size as the GDP and about four times the entire budget. Even with revenues running about $3 trillion a year, if we saved 5 percent of the revenues, that would not be much more than $150 billion a year. It would take us 110 years to pay off the debt—and that assumes we don't run anymore deficits! Gulp!

So if national debt is a perpetual burden, is it really possible to afford to run additional deficits? Yes! You do that by paying only the interest on the debt and then borrowing more money for the next year's deficit. It is the interest on the debt that is the true burden of the debt since those payments must be made every year, by all of us, forever! In other words, when we don't balance the budget this year, every generation that comes after us has to pay something for that inability to keep our fiscal house in order.

The concern about the interest payment burden of the debt is something that cannot be dismissed or even taken lightly. Low interest rates make it relatively easy to fund the debt. When you can borrow money at close to zero percent for short-term funds, that is a great way to fly. The interest payments are really low. But the real issue for the U.S. economy is what will happen as the debt rises and so do interest rates?

Consider the projections made by the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office. Interest payments could double over the next five years, from about $225 billion to about $460 billion.27 That is based on the fairly realistic assumption that the deficit will be cut in half over the next five years. Indeed, the deficit has been basically cut in half since its peak.

Nevertheless, even as the deficit shrinks, debt payments are likely to become a major problem because we have to make those payments before we spend money on anything else. We have to maintain our credit rating to keep those rates low, so we cannot miss a payment. Default is not an option.

But if the required interest payment doubles, it ultimately means there is less money for other purposes. In essence, the interest payments crowd out funds that could be used for other programs. The fear that the debt will become the beast that devoured the budget means that you cannot run large deficits for extended periods of time.

If the deficits must be reduced, how should that be done? That is, of course, a political decision since Congress and the president must come up with a budget that has smaller shortfalls.

To reduce the amount flowing into the debt load every year, either taxes will have to increase or spending will have to be reduced. Both of those actions, however, have significant implications since there is no such thing as a free tax increase or budget cut.

Consider spending cuts. First, you have to realize that even with a budget that is closing in on $4 trillion, there is not a lot of flexibility. Mandatory spending accounts for about 60 percent of the entire spending. This includes programs that we know as entitlements such as Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid. When you add in interest payments, the total approaches two-thirds of the entire budget, and when the Defense allocation and Homeland Security are included, you are looking at about 90 percent of the budget. In other words, if you don't cut entitlements or security spending, you cannot make any major dent in the deficit.

If you have decided that budget cuts are the way to go to reduce the deficit, what do you do, and what of the implications of those actions? Here you have to always keep in mind that when you cut the budget, you are making winner versus loser decisions. That is, someone will no longer receive the spending, while others continue to drink at the government's trough.

For example, let's say it makes sense to reduce spending on education but not on defense. Who are the winners? Clearly, if you do manage to buy more security with the higher defense outlays, then all of us win. But as we all know, not all the money that goes to the Pentagon buys us more security. It is not as if there isn't any waste in the defense budget. Actually, there is a lot of unnecessary defense spending, especially when it comes to creating real security.

And that gets us to the issue of pork. One of the biggest reasons it is so hard to cut the defense budget is that over the years, the Defense Department has managed to embed itself into large numbers of House districts. Cutting spending, then, might require a congressperson to vote for a cut in spending in his or her district. That is rarely good politics and tends to lead to a member of Congress becoming a former member of Congress.

Basically, everyone in Washington would like to tighten the government's belt, but only if someone else's belt is tightened. That is because pork is in the eye of the beholder. Rebuilding the Jersey shore after Hurricane Sandy devastated it seemed like a no-brainer, at least for those in the region. But for those in the heartland, it was nothing but wasteful spending. Meanwhile, northeastern politicians view farm subsidies as nothing but a waste of money, while farm-belt Congressmen think it is the linchpin upon which the nation's economy runs. It only matters if it matters to you.

Regardless, the winners of keeping defense spending up and reducing other outlays are all those firms that supply goods and services to the military.

Who loses when you cut education spending? Just as it is not clear that you buy more security with more defense spending, it is not clear that you have lower-quality education with less spending. It depends on where the cuts are made. If the government funds student loans at a lower level, the educational system is not affected, but some students simply will not be able to afford higher education and they may have to drop out of school.

If funds for school districts are cut, then it is likely that teachers or programs will have to be reduced. Those students who no longer have music, art, or advanced placement courses will be paying the price of reduced funding. Those students who are in larger classes but have trouble learning in those settings also are affected. However, those students who don't take art, music, or advanced placement courses or who can learn just as well in the larger classes suffer no loss. Even the losses are not evenly distributed.

Clearly, the trade-offs that must be made when cutting the budget are not simple or even obvious. In this example, if defense expenditures that don't add to security are continued but activities are cut that reduces educational attainment, there is a clear loss to the nation. However, it is also very possible that there is little change in educational attainment. It might even be possible to cut defense spending and not change our level of security.

The uncertainty about outcomes of budget cuts doesn't mean they cannot be made. They can and have to be. But there should be a clear-cut principle that determines what spending is reduced and what is sustained. Essentially, cut those programs or spending activities that create the least loss to society. Of course, since so much of that is judgment, and that determination is made in a political arena, it is likely that favored programs are saved, even if they add little to the economy, while those that have political enemies or little political backing will be reduced.

Keep in mind one last thing: The spending cuts do affect economic activity. If you cut the budget, you reduce government spending, and the demand for goods and services has to decline. That is simple math. That slows the economy, and an economy growing at a slower pace than expected will produce lower tax revenues than projected. That is also simple math. In the year that spending is cut, there is less demand. Period. That winds up offsetting, at least to some extent, the deficit reduction effects of spending reductions.

If you think that spending cuts are difficult, consider the alternative: tax increases. What taxes should be increased? Should we raise corporate taxes or income taxes? What about fees, which are really just taxes in disguise? The first question that has to be answered is who should be taxed.

Let's assume that you want to raise business taxes. There are dozens of ways of doing that. How it is done determines who is affected the most. Some taxes fall largely on large corporations, some on smaller ones.

How the tax is raised then will affect different types of companies in different industries. It is important to understand the negative impacts on businesses of any tax change. For example, if you implement a tax that falls heavily on small rather than large companies, will that accelerate the demise of the small business sector, which creates so many jobs?

According to the Small Business Administration, one-quarter of all small businesses fail in their first year, and that is a low estimate.28 Other studies have shown that rate rising to as much as 50 percent. Regardless, less than half the businesses make it to the five-year mark, showing how fragile that segment is. While larger businesses will also be hurt by tax increases, they might have greater capacity to withstand an increased burden. Who gets taxed matters, and thus the negative impacts depend on the type and the level of tax.

But most of all, the tax has to be able to raise the revenue that is needed to cut the budget deficit. That means it cannot be avoided. There are many ways to avoid a tax, but one way you don't want firms to react is by deciding to take their activities to another country. If a tax leads to a reduction in production in the United States, you wind up slowing economic growth, and that ultimately cuts the revenues from the higher tax.

Similar issues arise if you want to raise taxes on individuals. Should the taxes fall on all levels of income or just the wealthy or the middle class or even lower-income families? What you don't want to happen is for the tax increase to reduce demand. Why? Because if households cut back their purchases, the economy slows, and just like the problem with higher business taxes, the amount of taxes raised is not likely to be anything close to what is projected.

What is a good deficit-cutting person to do? Does all this mean taxes should not be increased? Hardly. Indeed, there are plenty of business and personal tax breaks that don't create any additional economic activity at all. What that means is that the tax break can be modified or even eliminated without reducing either business activity or household spending very much. That is where tax changes must be directed.

In other words, if the budget deficit is to be narrowed, you can cut spending, but only in certain ways, or you can raise taxes, but only in certain ways. There are no easy or simple answers to the question: “How do you reduce the deficit?” It depends on the context of the tax changes: who, what, when, and how.

Deficits continue to be run and the debt continues to grow. And that brings us to the little issue called the debt ceiling. The debt ceiling is the maximum amount of debt the U.S. Treasury may issue.

Interestingly, until 1917, the United States had no debt ceiling. Congress made its spending and tax decisions, and what could not be covered by revenues was simply borrowed. But the Second Liberty Bond Act of 1917 subjected the Treasury borrowing to a limit that could be changed only by an act of Congress. While the Treasury has basically free rein to decide how to manage the debt, it cannot just issue as much as it wants to.

While the Second Liberty Bond Act seemed to be a logical way for Congress to oversee domestic borrowing, chaos, not oversight, was introduced into the basic act of paying U.S. debts. Remember, the borrowing is being used to pay for spending that Congress already authorized. This is not new expenditures or outlays the president decided to make unilaterally. The new debt is used to pay for IOUs, including interest on the debt, which the government has already run up.

As benign as that act might have appeared when first passed, in Washington, no good deed goes unpunished. Instead of simply saying, “We bought it, we should pay for it,” some in Congress like to threaten not to raise the debt ceiling.

If Congress ever decided not to raise the debt ceiling, chaos would reign. While some bills could be paid as there was money coming in, there is no authority for the president to pick and choose what to spend those funds on. Indeed, it is not even clear the president could spend any money.

Though it is generally accepted that certain things such as defense and health care are essential functions that would be funded, what other bills would be paid are unclear. Either Congress would have to pass a bill stipulating the spending priorities in detail, or it would have to give the president carte blanche to determine how to spend the money. Could you imagine any Congress giving any president that kind of control?

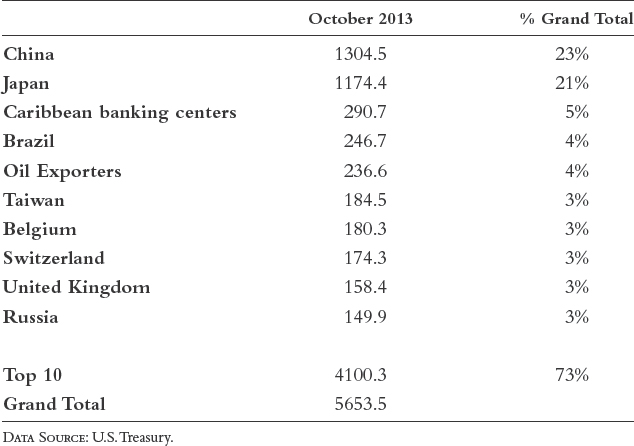

But the real risk is that interest on the national debt might not be paid in a timely manner. That could be catastrophic to the economy. The United States is considered to be the safe haven for world investors (see Table 7.2), and Treasury rates are viewed as riskless. Thus, there is tremendous demand for our securities, and that raises prices and lowers the interest rates we pay. Being a riskless security means investors don't need a little extra money to hedge against a potential default, and that also means our interest rates are lower.

Table 7.2 Major Foreign Holders of Treasury Securities (in billions of dollars)

Defaulting on an interest payment would change all that. Investors would pull money out of the United States and start demanding a higher rate to accept what is now a risky asset. Those factors would lead to a surge in interest rates and a major slowdown in the economy.

In addition, the dollar is considered to be the reserve currency of the world economy. Individuals, companies, and governments around the world hold dollars for transaction purposes. That is based in part on the safety of U.S. assets. A default would also end that status. The dollar would become a risky asset, it would be held less, and that would lead to a fall in its value.

What happens if the dollar falls sharply? The cost of imported products would rise rapidly. They would trigger rising inflation, further increasing interest rates. Rising prices would reduce consumer spending, and in conjunction with the higher interest rates, it would be very likely the economy would wind up in a recession.

If you doubt that a default would be a disaster, just ask the Greeks. When that country found it could no longer pay its debts, it had to be bailed out. Government spending was slashed; the economy crashed and unemployment rates soared, rising by 10 percentage points in a little over one year. Need we say more?

Ultimately, if Congress failed to raise the debt ceiling, the president might have to break the law by spending money as he pleased or act unconstitutionally by issuing bonds that Congress did not authorize. In other words, the president, the nation, and the economy would be in a pickle—or a constitutional crisis at the least.

Why would anyone think it is a good idea not to raise the debt ceiling and risk a default? Good question that seems to have no rational answer.

It is nice to think that fiscal responsibility means only balancing the budget and controlling taxes and spending. And even if you could pick and choose how to spend and tax, you have to recognize that you are also determining winners and losers. Deciding who are worthy to be the beneficiaries and who should be gored is something that only Solomon could determine.

Even if your wisdom were unlimited, you would still be at risk as projected levels of government expenditures and tax revenues ebb and flow with the business cycle. In other words, failing to recognize the context in which a budget decision is made is to make a failing budget decision. Context matters and, unfortunately, our politicians don't recognize that. We must.

Integral to budget decisions is the issue of taxes. In the next chapter, we look at how context does—or more often does not—affect how government decides to tax.

Notes

1. Michael Levine, Congressional Budget Office and Melinda Buntin, “Why Has Growth in Spending for Fee-for-Service Medicare Slowed?” CBO Working Paper Series, Vanderbilt University. August, 2013. www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/cbofiles/attachments/44513_MedicareSpendingGrowth-8-22.pdf.

2. Amitabh Chandra, Jonathan Holmes, and Jonathan Skinner, “Is This Time Different? The Slowdown in Healthcare Spending,” Presented at the fall 2013 Brookings Panel on Economic Activity, p. 6. www.brookings.edu/~/media/Projects/BPEA/Fall%202013/2013b%20chandra%20healthcare%20spending.pdf.

3. Levine et al.

4. Doug Elmendorf, director of the Congressional Budget Office, press briefing, September 17, 2013.

5. Chandra et al., p. 2.

6. Chandra et al., p. 5

7. California Healthline daily digest, August 29, 2013. www.californiahealthline.org/articles/2013/8/29/blue-shield-reduces-coverage-for-proton-beam-cancer-treatment.

8. Elmendorf press conference.

9. Cynthia Ogden, PhD, and Margaret Carroll, MSPH, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, study of the prevalence of obesity among children and adolescents by Division of Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys, June 2010. www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hestat/obesity_child_07_08/obesity_/hestat/obesity_child_07_08/obesity_child_07_08.htm#table1.

10. Ogden et al.

11. CDC Faststats. www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/overwt.htm.

12. CBO, 2013 Long-Term Budget Outlook, p. 27.

13. Elmendorf presentation at Brookings. Table: “Changes in Projected Medicare and Medicaid Spending between 2010 and 2020,” citing technical revisions that add up to $785 billion. September 19, 2013. www.brookings.edu/~/media/Projects/BPEA/Fall%202013/Fall%202013%20BPEA%20elemendorf %20presentation.pdf

14. Elmendorf press conference.

15. Ibid.

16. Medicare estimate from the Henry J. Kaiser Foundation. Population from U.S. Bureau of the Census. http://kff.org/medicare/state-indicator/total-medicare-beneficiaries/; www.census.gov/popclock/.

17. Elmendorf press conference.

18. Ibid.

19. Ibid.

20. Ibid.

21. Elmendorf, Brookings presentation, chart. www.brookings.edu/~/media/Projects/BPEA/Fall%202013/Fall%202013%20BPEA%20elemendorf%20presentation.pdf.

22. Moody's Investors Service, Analysis, United States of America, July 18, 2013.

23. U.S. Department of Treasury, Financial Management Service, Bureau of Economic Analysis data, Naroff Economic Advisors, Inc. analysis.

24. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Current Employment Statistics data, Naroff Economic Advisors, Inc. analysis.

25. National Bureau of Economic Research, “Business Cycle Expansions and Contractions.”

26. U.S. Department of Treasury. Joint Statement of Secretary Lew and OMB Director Burwell on Budget Results for Fiscal Year 2013, October 30, 2013.

27. CBO, Updated Budget Projections: Fiscal Years 2013 to 2023. July 2013 update.

28. Small Business Administration, Office of Advocacy, “Frequently Asked Questions.” September 2012 from Bureau of Labor Statistics, Business Employment Dynamics table on Entrepreneurship and the U.S. Economy.”