7

DETAILED HISTORY AND PERFORMANCE MEASURES MODELS

The detailed history and performance measures modeb are created to make sense of results being achieved. The detailed history model does this by drilling down into a particular result to reveal the detail behind the numbers. The performance measures model takes a high-level view by combining summaries of internal performance with external data to create industry related comparisons.

REPORTING PAST AND FUTURE PERFORMANCE

Relevance

Field Marshal Arthur Wellesley, otherwise known as the Duke of Wellington, was one of the leading military and political figures of the 19th century. He was commissioned into the British Army in 1787 and rose to the rank of general. One of his more prominent campaigns resulted in the defeat of Napoleon in the Battle of Waterloo in 1815. He is famous for his extensive planning before battles, which left him able to score victories against larger superior forces at minimum cost to his own troops.

According to various online encyclopaedias, the Duke of Wellington is regarded as one of the greatest defensive commanders of all time, with many of his tactics and battle plans studied in military academies around the world. He is also known for his disregard of ineffective and inefficient bureaucracy, as can be seen from the following letter he is said to have written in 1812 while leading an army in Spain:

Gentlemen

Whilst marching from Portugal to a position which commands the approach to Madrid and the French forces, my officers have been diligently complying with your requests, which have been sent by HM ship from London to Lisbon and thence by dispatch rider to our Headquarters.

We have enumerated our saddles, bridles, tents and tent poles and all manner of sundry items for which His Majesty’s Government holds me accountable. I have dispatched reports on the character, wit and spleen of every officer. Each item and every farthing has been accounted for, with two regrettable exceptions for which I beg your indulgence.

Unfortunately the sum of one shilling and nine-pence remains unaccounted for in one infantry battalion’s petty cash and there has been hideous confusion as to the number of jars of raspberry jam issued to one cavalry regiment during a sandstorm in Western Spain. This reprehensible carelessness may be related to the pressure of circumstances, since we are at war with France, a fact which may come as a bit of a surprise to you gentlemen in Whitehall.

This brings me to my present purpose, which is to request elucidation of my instructions from His Majesty’s Government so that I may better understand why I am dragging an army over these barren plains. I construe that perforce it must be one of two alternative duties, as given below. I shall pursue either one with my best ability, but I cannot do both:

To train an army of uninformed British Clerks in Spain for the benefit of the accountants and copy-boys in 1. London, or perchance

To see to it that the forces of Napoleon are driven out of Spain 2.

Your most obedient servant

Wellington

Whether Wellington actually wrote the letter or not does not concern us here, but as this book’s authors, we suspect that many of you have wanted to write something similar to your boss. It seems that the focus of management reporting is often on the insignificant, and the real issue of achieving the organisation’s purpose is forgotten. What is more important: being over budget on stationery by 10 percent this month or beating the competition? It is an issue of materiality versus relevance.

You can tell a lot about an organisation’s priorities by looking at the management reports through which people and departments are judged.

Context

A natural consequence of any kind of plan is the variances that arise when monitoring what actually happened. The more detail kept within a plan, the more variances that will be generated. The more variances there are, the more management time and effort will be required to analyse and interpret what they mean.

Herein lies the problem. Technology has allowed vast amounts of detail to be planned and tracked. Computer systems can quickly and effortlessly go through a sea of data, spitting out variances and trends. They can then sort, rank, and chart that data in many weird and wonderful ways. But systems typically require management skills to assess what is relevant and what is not. To determine relevance requires results to be placed in context of what really matters.

As an example, take a report that shows we are over budget on travel expenses by 15 percent. Is this a good or bad performance? Well, it depends. If that overspend was due to visiting 20 key customers in trying to secure future sales orders, then it was probably well worth the cost. But if it was spent attending a range of internal meetings, then who knows?

The trouble is that quite a lot of management decisions are made on variance reports that have no context. How many readers have had their expenses cut (or expected revenues increased) simply because actual results disagreed with budgets? Indiscriminate cost cutting can easily result in key initiatives that are crucial for future growth to be starved of essential resources. Or how about a report that shows that a department is 20 percent under on costs? It is easy to assume that there is nothing to worry about, and so no action is required. The result of this decision (deciding to do nothing is still a decision) means that allocated resources that could be better used elsewhere are wasted. It could also mean that key activities are not being carried out, or not carried out to the level that is required for future goals.

Connected to this question of relevance is the standard to which performance is compared. In most organisations, this will be against the numbers negotiated when the budget was set. However, is this standard good enough in the real world? Let’s suppose for a moment that the budget was based on an assumed business environment. What if those assumptions turned out to be wrong? For example, if when setting a revenue target an assumption was made that the market growth was 10 percent, but the growth turned out to be 20 percent. It would mean that an on-target performance could be bad, as market share would be lost.

Too often, organisations compare their performance with numbers they established at the start of the year. If these are not presented in the context of what the market is doing, then variances become at best meaningless, and at worst can cause the organisation to make decisions that are wrong.

Data Issues

It is essential for those making decisions based on past performance to recognise that the data being presented may not tell the whole story. Ignoring the issues of relevance and context mentioned previously, the data may also incorporate one or more of the following issues:

• Data accuracy. Actual results are typically held in other systems, such as the general ledger. To transfer these into the planning models for reporting will require values to be summarised, translated, and mapped into the right measures. Depending on the source system and the data acquisition capabilities of the planning technology, this may not be a simple task. Even when the transfer routines have been set up, changes within the source systems (for example, adding new measures or changes to operational structures) could invalidate how results appear within reports.

Then there is the issue that the source data itself may be in error, all of which can lead to data integrity issues. The only way to check is to have some kind of validation procedure that gives confidence that results being reported are of the highest data quality. This will almost certainly mean that a user should be able to interrogate any number in a report to see how it has been translated from its source to the appropriate planning model.

• Timing issues. Variances are calculated at a moment in time. Although data may be correct within a model, because there is a delay between what is held and what may now be the truth, the data can lead to unexpected results. Of course, models could be set up so there is a dynamic link to the source systems, but this leads to another problem: the result someone saw yesterday that sparked a conversation with other managers has mysteriously changed overnight. Assuming that only some people noticed the change, it appears that the data is randomly changing and is therefore unreliable. After all, how can managers be sure it will not change again in the next few minutes and therefore cause people to doubt what the numbers are actually revealing?

A solution to this dilemma is to have a cut-off point in time that everyone agrees to. This assures that reports are made of detailed data that existed within the transaction systems at that point in time. To complement this, comparisons should be allowed between the results that exist now and the cut-off point. This would indicate that any variances between the two versions are either down to errors being corrected or were subject to timing issues when recorded.

• Hidden horrors. Variances may show that a particular measure is on track against plan, but hidden beneath the value may be individual items that mask what is really going on. For example, there may not be a variance on a particular revenue stream, but when looking at the detail there could be some customers or donors whose revenues are way under what was expected and is being offset by other revenue items that are unexpectedly way over. The only time this is discovered is when the good variances become on target, leaving the bad performing results with nowhere to hide.

Of course, you could print out every conceivable variance, but two issues then arise. First, it may not be possible to plan at this level of detail, in which case there will be no variances to calculate. Second, the more variances that are generated, the more time someone has to spend in investigating them. Investigations take time and distract management away from what they should be doing: securing the future. To overcome this, systems should automatically trawl through the detail and look out for abnormal variances that are being covered up at the summary level. These variances should be brought to management’s attention as exceptions to what is being reported.

• Trends. Because of their point-in-time nature, variances cannot show whether there is an on-going trend. Trends are not obligated to fall in line with an organisation’s planning calendar and may span multiple years before they are noticed. This requires data to be assessed at a detailed level over multiple years and with different spans of time. Retailers are typically good at this, and most plan according to the industry’s different seasons, which may or may not fit in with their fiscal calendar.

• Abnormal events. The last issue we will cover here is that, by themselves, variances cannot show whether they were caused by a one-off event or are part of an on-going trend. There are many organisations where an abnormal performance in one month (for example, 20 percent over sales due to an unusual client purchase) generates a target for the following year that has been set by applying an arbitrary growth rate. Assuming for a moment that growth is likely, applying it to a previous abnormal event means we now have a target that is unrealistic.

This also happens with expenses. Many of you will be familiar with the urge to unnecessarily spend your entire budget in the current year, because if you do not you will lose it in the next year. This sort of game-playing is hard to justify unless you look at the detail behind the numbers to highlight what is abnormal and what the real trends are.

The issues covered here apply to both actual results and those being used as forecasts. To tell a more insightful story behind any number requires detail. The level of detail will differ depending on what managers need to know in order to take insightful decisions.

REPORTING PERFORMANCE FROM THE PLANNING FRAMEWORK

Bearing in mind the previous comments, the business planning framework prescribes two logical models whose role is to provide relevance and context and which can be assessed for data issues. These models compliment the operational activity model (OAM) described in chapter 5, ‘Operational Activity Model’. The OAM is designed to answer the following questions:

• what did we achieve against the plan in relation to resources, workload, and outcomes for each business process?

• How are each of these looking for the future? Is performance getting better or worse?

Variances will indicate that some things are not going according to plan and will need to be investigated. Similarly, there will be underlying trends that may not surface in the OAM reports, and so these too will need to be identified and researched. That is the aim of the models described in this chapter, which provide backup to the OAM.

There are two types of models that can be used when reviewing actual and forecast results:

• The detailed history model (DHM) supports investigations into past performance. It focuses on what went on internally within the organisation at a detailed level.

• The performance measures model (PMM) takes a higher, external view of performance that is related to what is going on in the business environment and in comparison to competitors or peers.

These models are now described in more detail.

IDENTIFYING DHMS

Given that the focus of the DHM is in analysing actual results reported in the OAM, the starting point in deciding what models to create are the measures held within that model. As explained in chapter 5 ‘Operational Activity Model’, measures are grouped into those that monitor objectives, business process goals, performance measures, activity measures (that can be split into work done and outcomes), risk, assumptions, income, and resources.

Of these, the ones that can be broken into further detail are those that deal with income and resources, as these will be made up of transactions held within the general ledger. Some of the workload and outcome measures may also have further details, which can be used to analyse business process activity.

It is not desirable to create DHMs for every measure, as this could distract management from what is important. Instead, DHMs should be created for those measures whose values play a significant part in either directly resourcing or monitoring a business process.

When defining a DHM, the question should be asked, ‘What information do I need in order to understand the actual results being presented in the OAM’? The answer to this question determines the level of detail, the analyses that are required, and the type of history model that will meet those needs.

In chapter 4, ‘Business Planning Framework’, we outlined three types of DHM, each of which provides a different type of support:

• Transaction data set. These are tables of data that can be queried and summarised. An example of this type could contain the general ledger transactions behind each account code. These would be loaded from the General Ledger (GL) on a regular basis and could consist of date, department, account code, supplier, and amount. Capabilities within the DHM would summarise this data by department, month, and account codes that are then fed into the appropriate place within the OAM.

The way it would be used would be to support a particular expense query. For example, if there was a variance in the travel budget, the user would be able to drill down into the supporting DHM to see the transactions that made up the actual result. The user could then issue another query that extracts transactions for a prior month to see if any expenses had been held over and hence had caused this months variance.

As with the other types of DHM, the ease of use and capabilities provided to an end user will depend on the technology solution being used. As a minimum, this type of DHM should support the following examples:

○ Filters. List all transactions making up a particular account code.

○ Summaries. Total all transactions for a particular account code and over a selected period.

○ Sorting and ranking. Show the top 10 departments as ranked by travel expenditure. o Secure access. The content held within a DHM should automatically filter out data that the user is not allowed to see.

• Multi-dimensional model. This second type of DHM allows users to produce cross-tabular analyses. Data is stored and referred to by its business dimensions. Users then have free access to the way in which data is presented, which can incorporate charts, additional calculations, and colour-coded exceptions. Examples of this type of model include sales analyses that could include types of customers, products sold, discounts provided, returns, and shipping costs.

Unlike the transaction data set, a multi-dimensional model is able to provide the following:

○ Multiple views of the data. For example, show sales revenue by product and customer, customer profitability, returns by product and location.

○ Trends. For example, calculate a rolling 12-month average and show this by month for the current year versus last year.

○ Exceptions. For example, show all customers whose year-on-year growth has been negative.

• Unstructured model. This final type of model is for providing non-numeric support, such as links to news reports, social media discussions, and competitor product videos. By linking these into the OAM, qualitative information can be provided that can make a substantial difference in the way results are perceived.

CASE STUDY—DHMS

In our XYZ, Inc. case study, the following three DHMs have been defined: sales analysis, human resources (HR), and general expenses.

Sales Analysis

This is a multi-dimensional model that is used to review past sales and spot trends in product groups. The dimensions and members of the model were set as follows:

• Region Members are the sales region of the United States, Europe, and Asia.

• Customer. Members are customers whose revenue exceeds $50,000 in a year. Customers with smaller revenues are summarised as ‘other’ for analysis purposes.

• Product. Members are the product lines offered.

• Channel. Members are ‘direct’ and ‘on-line’ to distinguish between how the product was purchased.

• Year. Members are the past three years.

• Period. This is set at weeks within a year.

• Measures. The members include the following:

○ Volume. The quantity of each product ordered.

○ Gross revenue. The total amount charged for each product.

○ Discount. The amount of any discount given on each product.

○ Net revenue. The amount invoiced.

From this DHM, users can produce analy ses regarding the products being sold, through which channels, in what areas, and the profit margins being achieved. This is calculated from the detailed sales data by product and customer. Figure 7-1 is an example of the kind of report that can be produced.

Figure 7-1A: Sample Sales Analysis Report to Back Up Results Stored in the Operational Activity Model

Figure 7-1B: Sample Sales Analysis Report to Back Up Results Stored in the Operational Activity Model

HR

This is a transaction data set used to monitor staff and welfare entitlements. The fields defined for each record are as follow s:

• Period (that is, the period to which this record belongs)

• Employee name

• Title

• Salary grade

• Department

• Status (for example, full-time, part-time, no longer working)

• Basic salary paid

• Overtime amount paid

• Pension contribution paid

• Hours worked in period

The table is updated each period with records being appended to build up a history of employee costs. These records can then be selected and summarised via queries to provide a picture of how costs change by grade over time. Table 7-1 depicts a sample table of a history of employee-related costs.

Table 7-1: Sample Employee Table to Back Up Costs Reported in the Operational Activity Model

General Expenses

This last transaction data set holds transactions for all expenses except those relating to HR. It is used to provide detailed reports behind every expense item as recorded in the general ledger. The fields in the table have been set as follows:

• Date of transaction

• Account code

• Department

• Supplier

• Invoice number

• Detail

• Amount

• Partial or full payment

Table 7-2 presents a sample expenses table.

Table 7-2: Sample Expenses Table With Detailed Transactions, as Recorded in the General Ledger

DEFINING THE PMM

PMM Content

As mentioned earlier, while the DHM looks at past performance in light of what happened internally, the PMM in contrast takes an outward view that looks at past and future performance in light of what is going on in the market.

In order to do this, the PMM has a number of industry-recognised measures, which require a range of additional data to be collected that may not exist within the OAM. It is not the purpose of this book to recommend what those measures should be, as they are not necessarily applicable to all industries. Some will be dependent on the management methodology being used to manage the company. For example, if the organisation subscribes to total quality management practices, then a range of measures will have already been defined, as would those whose practices support economic value added principles. What is important is that the measures cover a range of business areas that can be related to the organisation’s business processes.

Bernard Marr, a leading authority on organisational performance, has produced a book on measures. Key Performance Indicators: The 75 Measures Every Manager Needs to Know has a great selection of key performance indicators that has been grouped into the topics typically found in the perspectives of a balanced scorecard.

The book answers key questions on why the measure is useful, how to calculate and interpret the measure (with examples), what its limitations are, and where to find out more information. It also includes measures on the impact of social media and how to calculate an organisation’s social networking footprint. If you are challenged with identifying and selecting what you should be measuring, then this book is worth reading.

PMM Business Dimensions

For the XYZ, Inc. case study, the PMM consists of the following dimensions and members:

• Organisational departments.

• Versions that include current year actual, current forecast, target, and benchmark. The latter is used to hold industry standard values where available. This dimension could also be extended to hold comparatives to major competitors.

• Time is held as quarterly totals, as this is seen to be sufficient for management purposes.

• Measures are those that are used to calculate performance as viewed from a market perspective, some of which already exist within the OAM.

Case Study Measures for XYZ, Inc.

The following measures, which monitor performance across a range of business areas, have been defined within the PM M.

Financial Performance

These measures are the familiar ones of the following:

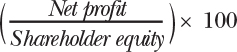

• Return on equity. This has been set as one of XYZ’s corporate goals. It is measured using the following formula:

Net profit and shareholder equity come from the OAM and are included within the PMM.

• Working capital ratio. This measure helps XYZ to compare the working capital employed with competitors in the same industry. It is calculated by the following formula:

Values for these measures come from the OAM.

Customer Performance

Retaining customers is vital to XYZ’s future success. To help them monitor performance in this area, they use the following measures:

• Customer retention rate. This is calculated by the following formula:

Number of customers at start of year/Number of customers at end of year

XYZ’s management would always want to see this rising. The number of customers is not held in any planning model, so these are loaded directly into the PMM from the internal customer relationship management system.

• Customer complaints. This is a straightforward statistic that is collected directly from XYZ’s support system.

Marketing Performance

Given the potential growth of online ordering, the performance of Web-based marketing activities is crucial to future success. To grow, XYZ must be able to utilise the power of search engines and social media sites. To monitor performance in this area, two measures are used that only appear within the PM M:

• Search engine ranking. This is measured by keyword, and results are provided directly from the relevant search engines. The aim is to see which keywords provide the best value in terms of how XYZ is ranked and the cost involved. To calculate this, the PMM reports 20 selected keywords in terms of rank, click-through rate, and the marketing amount spent on each one.

• Klout score. The values for this measure are provided directly by the third-party organisation of the same name. Klout uses around 35 variables on Facebook and Twitter to come up with a score of between 0 and 100. Zero indicates that XYZ’s social media activity is having no influence on users, but a score of 100 indicates that XYZ is having total influence on what is being discussed. Klout scores are free and provide an interesting way of monitoring social networks.

Operational Processes

Operational process measures allow management to assess how well its production facility is performing. The measures in this area include the following:

• Capacity utilisation rate. This is measured by the following formula:

The result indicates whether there are efficiencies to be gained and whether there are any issues with the production process. If these measures were to be set as business process goals, then they would be stored within the OAM. As it is, they are being kept just within the PMM.

• Quality index. This measure indicates whether the products being sold are fit for purpose, which directly impacts customer satisfaction and hence any reorder rate. There are many ways in which this can be measured, with most organisations tracking several quality measures. For XYZ, they monitor product returns, which are loaded directly into the PMM from the sales order system.

Employee Performance

This set of performance measures looks at employee relationships. Two measures are deemed important to XYZ:

Revenue per employee. This measure looks at how much revenue is generated for each person employed. Because employee costs form a significant proportion of overall costs, it is essential that this does not increase as online sales cause prices to drop. Both parts of this measure come from the OAM.

Employee churn rate. This measure reports staff turnover and is generated from values loaded directly from the internal HR system.

Social Responsibility

This last set of measures are seen by management as crucial to the way XYZ is viewed. Social responsibility is an increasingly important discussion point on social media sites, so XYZ is keen to promote its ‘green’ credentials. The chosen measures only exist within the PMM and consist of the following:

• Carbon footprint. This measure expresses the amount of carbon dioxide emitted as part of the production process. Values are reported as the number of units per ton, with a target level set at 18 tons per year. The industry average is around 20 tons per year.

• Energy consumption. This measure is related to the last in that it provides management with a way to promote XYZ as being more socially advanced. The value is calculated as the amount of energy purchased in a quarter, which can then be related back to the energy consumption used to produce each unit of product.

Reporting From the PMM

There are many ways in which measures stored within the PMM can be reported. One of the better ways is as a dashboard that uses dials that compare actuals to targets for the purpose of monitoring how the organisation is performing in each category. These dials can be set to display variances from target, from plan, and from an industry benchmark.

Where performance is lacking, management can develop initiatives within the strategy improvement model to bring the organisation back into line with the targets set.

This completes our description of the models that provide insight into past performance. The next chapter looks at the OAM support models that are used to predict the future.