CHAPTER 12

Risk Appetite Statement

INTRODUCTION

In recent years, many companies have scrambled to meet the stringent post-recession regulatory requirements by instituting new ERM plans or augmenting existing programs. However, regulatory compliance is not enough. In order for ERM to create value, companies must seamlessly integrate risk practices into the organization's day-to-day business processes at every level. A key lever for this is to implement a comprehensive risk policy that establishes metrics, exposure limits, and governance processes to ensure enterprise-wide risks are within acceptable levels.

At the heart of such a policy is the risk appetite statement (RAS). An RAS is a concise document that provides a framework for the board of directors and management to address fundamental questions with respect to strategy, risk management, and operations, including:

- What are the strategies for the overall organization and individual business units? What are the key assumptions underlying those strategies?

- What are the significant risks and aggregate risk levels that the organization is willing to accept in order to achieve its business objectives? How will it establish governance structures and management policies to oversee and control these risks?

- How does the company assess and quantify the key risks so that it can monitor exposures and key trends over time? How does it establish the appropriate risk tolerances given business objectives, profit and growth opportunities, and regulatory requirements?

- How does the organization integrate its risk appetite into strategic and tactical decision making in order to optimize its risk profile?

- How will the company establish an ERM feedback loop and provide effective reporting to the board and senior management?

Corporate directors may well recognize the need for a formal statement of risk appetite, but according to a 2013 National Association of Corporate Directors (NACD) study, only 26% of companies actually have one.1 In this chapter I'll offer a set of guidelines, best practices, and practical examples for developing and implementing an effective RAS framework. Specifically, we'll look at the requirements of a risk appetite framework; the process of developing, implementing, and refining an RAS; and the monitoring and reporting processes that will ensure ongoing observance. We'll conclude with a practical example of an RAS that includes illustrative metrics and tolerance levels for key risks.

REQUIREMENTS OF A RISK APPETITE STATEMENT

A well-developed risk policy in general and an RAS in particular must have the following attributes:

- It is a key element of the overall ERM framework, specifically the governance and policy component.

- It is aligned with the business strategy and expressed with quantitative risk tolerances.

- It reinforces the organization's desired risk culture and is aligned with risk culture levers (e.g., tone from the top, people, training, etc.).

- It produces better risk-adjusted business performance, and thus enhances the organization's reputation with key stakeholders.

Figure 12.1 provides an overview with these key attributes and the linkages between ERM, risk appetite, risk culture, and reputation.

FIGURE 12.1 Key ERM Linkages

A risk appetite statement is a board-approved policy that defines the types and aggregate levels of risk that an organization is willing to accept in pursuit of business objectives. It includes qualitative statements and guidelines as well as quantitative metrics and exposure limits. The RAS is implemented through a risk appetite framework, which includes the common language, policies, processes, systems, and tools used to establish, communicate, and monitor risk appetite. The risk appetite framework should incorporate the following elements:

- Risk capacity (also known as risk-bearing capacity) represents a company's overall ability to absorb potential losses. Risk capacity can be measured in terms of cash and cash equivalents to meet liquidity demands and in terms of capital and reserves to cover potential losses. Companies in highly regulated industries, such as banking, may define their risk capacity conservatively as the capital set aside to absorb potential losses under adverse scenarios. This may be the capital that would permit them, for instance, to pass regulatory stress tests. Other companies, such as technology startups, might have a more aggressive definition of risk capacity that encompasses the capital and resources that could be lost to a point just shy of insolvency in a relatively short timeframe (e.g., until the next round of funding). The commonality among these calculations, however, is that they represent the absolute maximum loss a company is able (not simply willing) to take on. Risk capacity should also take into consideration an organization's skills, tools, and performance track record in managing risks. Consider two companies with similar risk profiles and capital levels: The one with superior risk management would have greater risk capacity.

- Risk profile is a snapshot of an organization's risk portfolio at a specific point in time (past, present, or future). It is crucial for the risk profile to align with the business model and strategy of the organization. For example, one company may choose to be a low-cost provider, in which its risk profile is driven by low profit margin (i.e., weak pricing power) and significant operational risks (e.g., cost control, supply-chain management, and scale economics). Conversely, another company could choose to be a high-quality, value-added provider, where its risk profile is driven by a high profit margin and significant strategic and reputational risks (e.g., product innovation and differentiation, customer experience, and brand management). The current risk profile of an organization is determined by all of the underlying risks embedded in its business activities, whereas the projected or target risk profile would also include business-plan assumptions.

- Risk-adjusted return provides the business and economic rationale for determining how much risk an organization should be willing to accept. In fact, an organization should not be willing to accept any risk if it is not compensated appropriately. Conversely, if the market is providing a higher than expected return, then an organization should be willing to increase its risk appetite (while still considering its risk capacity as discussed previously). At the inception of any business transaction, the risk originator must establish an appropriate risk-adjusted price that fully incorporates the cost of production and delivery as well as the cost of risk (i.e., expected loss; unexpected loss or the cost of economic capital; insurance and hedging costs; and administrative costs). I cannot emphasize enough the importance of risk-adjusted pricing! Although every business takes risks, it has only one opportunity to receive compensation for them: in the pricing of its products and services. In addition to pricing, organizations use a range of tools—Economic Value Added (EVA®),2 economic capital (EC), and risk-adjusted return on capital (RAROC)—to measure risk-adjusted profitability, evaluate investment and acquisition opportunities, and allocate capital and other corporate resources. It is important that these tools accurately account for risk.

- Risk appetite represents the types and aggregate levels of risk an organization is willing to take on to actively pursue its strategic objectives. It should fall within the broader umbrella of risk capacity and, in the best possible scenario, will align closely with the organization's current risk profile. A high risk appetite will consume a greater portion of risk capacity, while a low risk appetite will consume a smaller portion, thus providing a greater buffer zone and reducing the vulnerability of the organization's capital and resources. A company's risk profile should closely resemble its risk appetite. In reality, however, it is very challenging for companies to have a clear understanding of their enterprise risk profile, which may be masked by risk assessments created in organizational silos, poorly understood correlations, and inadequate analysis of earnings and value drivers. Gaining a full understanding of a company's risk profile—and, subsequently, its risk appetite—is what makes an RAS particularly valuable. When a company's risk profile is out of sync with its risk appetite, management should make course corrections to bring the two closer in line.

-

Risk tolerance is often used as a synonym for risk appetite, but in practice it is quite different and plays an important role in the risk appetite statement. Risk tolerances are the quantitative thresholds that allocate the organization's risk appetite to specific risk types, business units, product and customer segments, and other levels. Certain risk tolerances are policy limits that should not be exceeded except under extraordinary circumstances (hard limits) while other risk tolerances are guideposts or trigger points for risk reviews and mitigation (soft limits). Whereas risk appetite is a strategic determination based on long-term objectives, risk tolerance can be seen as a tactical readiness to bear a specific risk within established parameters. Enterprise-wide strategic risk appetite is thus translated into specific tactical risk tolerances that constrain risk-acceptance activities at the business level. Risk tolerances are the parameters within which a company (or business unit or function) must operate in order to achieve its risk appetite. Once established, these parameters are communicated downward through the organization to give clear guidelines to executives and managers and also to provide feedback when they are exceeded. For this reason, risk tolerance should always be defined using metrics that are closely aligned with how business performance is measured (i.e., key risk indicators should be closely related to key performance indicators).

Establishing risk tolerance levels is one of the major challenges in developing an RAS framework, but it is essential to its success. There are many ways to determine risk tolerances. It is up to each organization to decide which ones work best. Table 12.1 offers some approaches that an organization may take to determine risk tolerance levels. Please note that these approaches are not mutually exclusive. Sometimes, a blended approach is best. For example, one may initially set a risk tolerance level using statistical analysis (95% confidence level observation) and then adjust it up or down according to management judgment.

Table 12.1 Approaches to Establishing Risk Tolerance Levels

| 1. | Board and management judgment |

| 2. | Percentage of earnings or equity capital |

| 3. | Regulatory requirements or industry benchmarks |

| 4. | Impact on the achievement of business objectives |

| 5. | Stakeholder requirements or expectations |

| 6. | Statistics-based (e.g., 95% confidence level based on historical data) |

| 7. | Model-driven (e.g., economic capital, scenario analysis, stress-testing) |

While the main purpose of an RAS framework is to establish limitations on risk, it also provides other important benefits, including:

- Developing a common understanding and language for discussing risk at the board, management, and business levels.

- Promoting risk awareness and enforcing the desired risk culture throughout the organization.

- Aligning business strategy with risk management to provide a balance between financial performance and risk-control requirements.

- Quantifying, monitoring, and reporting risks to ensure that they are within acceptable and manageable levels.

- Embedding risk assessments and risk/return analytics into strategic, business, and operational decisions.

- Integrating risk appetite with other ERM tools, including risk-control self-assessments (RCSAs), key performance indicators (KPIs) and key risk indicators (KRIs), economic capital, and stress-testing.

- Meeting the needs of external stakeholders (e.g., regulators, investors, rating agencies, and business partners) for risk transparency; safety and soundness; and environmental and social sustainability.

DEVELOPING A RISK APPETITE STATEMENT

The development of the RAS is an important early component of ERM program deployment. It provides significant strategic, operational, and risk management benefits because it informs risk-based decision making for the board of directors; executive management; risk control and oversight functions (risk, compliance, and internal audit); and business and operating units. The implementation requirements for an RAS depend on the size and complexity of the organization; the business and regulatory environment in which it operates; and the maturity of its ERM program. The following provides some general guidelines for developing an RAS and for refining it on a continuous basis.

Step 1: Assess Regulatory Requirements and Expectations

As part of a larger ERM effort, an RAS offers far greater value than merely meeting regulatory requirements. Nonetheless, aiding the process of meeting such requirements is a significant benefit. Whether or not it is actually required by specific laws, regulations, or industry standards, an RAS offers a systematic and holistic approach to controlling risk exposures and concentrations. Successful deployment of an RAS can address the requirements of several common regulatory schemes. Consider the following examples from the financial services industry:

- U.S. Securities & Exchange Commission (SEC). As part of a global collaborative effort of 12 supervisory agencies from 10 countries, the SEC issued a report in December 2010 that evaluated how financial institutions have progressed in developing risk appetite frameworks, including IT infrastructures and data aggregation capabilities.3

- U.S. Federal Reserve (Fed). The Fed's Consolidated Supervision Framework for Large Financial Institutions, released in 2012, directs that each firm's board of directors, with support from senior management, should “maintain a clearly articulated corporate strategy and institutional risk appetite.” It further stipulates “that compensation arrangements and other incentives [be] consistent with the corporate culture and institutional risk appetite.”4

- Financial Stability Board (FSB). In November 2013, the FSB enhanced its regulatory guidance on ERM and the RAS framework. This regulatory guidance included key terms and definitions and, more important, established regulatory expectations for the board.5

- U.S. Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC). In 2014, the OCC set forth guidelines for financial institutions that include “a comprehensive written statement that articulates the bank's risk appetite, which serves as a basis for the risk governance framework.”6

- Own Risk and Solvency Assessment (ORSA). Instituted by the National Association of Insurance Commissioners (NAIC) in 2014, ORSA affirms that “a formal risk appetite statement, and associated risk tolerances and limits, are foundational elements of risk management for an insurer; understanding of the risk appetite statement ensures alignment with risk strategy by the board of directors.”7

While these regulations are focused on banks, insurance companies, and other financial institutions, organizations in other industry sectors can benefit from the standards and guidelines they provide. Moreover, all companies should understand the RAS framework expectations established by global stock exchanges, rating agencies, and other organizations such as the National Association of Corporate Directors (NACD), Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission (COSO), and the International Organization for Standardization (ISO).

Step 2: Communicate the Business and Risk Management Benefits of the RAS

Senior management must set the tone at the top and communicate the critical role that the RAS plays in the risk-management process. This communication should come from the CEO, CFO, CRO, and other senior business leaders and be directed at key internal stakeholders. Such communication may take place in town hall meetings, workshops, corporate memos, or e-mails. It should clearly articulate the support from the board and corporate leaders and provide the implementation steps, expected benefits, regulatory requirements, industry standards, and business applications of the RAS for key stakeholders. Additionally, internal stakeholders who are responsible for developing and implementing the RAS framework should receive appropriate training.

Step 3: Organize a Series of Workshops to Develop the RAS

With the appropriate communication and training completed or well underway, the organization is ready to develop the RAS. The executive sponsor (e.g., the CRO or CFO) of the RAS should organize a series of workshops with risk owners (e.g., business and functional leaders) to develop the risk appetite metrics for their organizational units while the CEO and key executive team members develop those for the overall enterprise. The purpose of these workshops is to develop the RAS with input from all of the risk owners by addressing the following questions sequentially:

- Business Strategy: What are the business strategies and objectives for each business unit or function? What are the key assumptions underlying these strategies?

- Performance Metrics: What are the KPIs that best quantify the achievement of these business or process objectives? What are the performance targets or triggers for these KPIs?

- Risk Assessment: What are the key risks that can drive variability in actual vs. expected performance?8

- Risk Appetite: What is the company's appetite for each of these key risks? What are the KRIs that quantify the exposure levels and/or potential loss? What are the limits or range of tolerances for these KRIs?

Figure 12.2 provides a diagram of the logical flow of these questions in the context of a risk/return bell curve. Unfortunately, many companies break down this logical flow by separating the strategy and ERM components. These companies generally define strategic objectives and KPIs as part of strategic planning (Steps 1 and 2 in Figure 12.2) and provide reporting to the executive committee and the full board. Separately, they perform risk assessments and develop KRIs as part of ERM (Steps 3 and 4) and provide reporting to the ERM committee and the risk or audit committee of the board. The integration of strategy and ERM (integrating Steps 1 through 4) provides much better analysis, insights, and decision-making, including the alignment of KPIs and KRIs for the RAS framework. In other words, don't dissect the bell curve and look at return and risk separately!

FIGURE 12.2 Distribution of Outcomes

These workshops might take place over the course of a few months. By the end of this step, the executive sponsor should be satisfied with the quality of the initial risk-appetite metrics and risk tolerance levels. The key objective of these workshops is to develop an initial set of KPIs and KRIs with their performance targets and risk tolerances, respectively. Some of the proposed metrics might be aspirational, and the risk owners will need time to flesh them out with real-world data. A subset of available metrics will be the basis of a prototype RAS and dashboard report in the next step.

Step 4: Develop and Socialize a Prototype RAS and Dashboard Report; Produce a Final RAS Based on Board and Business Feedback

Based on the output from Step 3, the team can produce a prototype document for the RAS to generate discussion and kick off what will become an iterative process. This document should include the RAS framework, a dashboard report with risk appetite metrics, and the RAS itself with qualitative statements and quantitative risk tolerances. (For more, see “Examples of Risk Appetite Statements and Metrics,” below.)

The executive sponsor can use this prototype document to socialize the prototype RAS and obtain input from corporate and business executives as well as select members of the board of directors (e.g., chairs of the risk and audit committees). Based on management and board feedback, the team can then produce a final RAS framework and dashboard report.

Step 5: Obtain Executive Management Approval

At this stage, the RAS is ready for management consideration. The executive team should take the time to discuss and vet the RAS thoroughly. This discussion may lead to changes in the risk appetite statement, metrics, and/or risk tolerance levels. Once this is complete, the executive committee or ERM committee would issue final approval.

Step 6: Obtain Board Approval

The RAS should next be reviewed by the full board of directors, who will similarly discuss and challenge it. A key objective in this step is to establish a concise set of risk-appetite metrics and risk tolerance levels that are appropriate for board-level oversight and reporting. Final approval may come from the risk committee, audit committee, or the full board. Nonetheless, the full board should review the RAS in the context of the overall corporate strategy.

Step 7: Communicate the RAS, including Roles and Responsibilities

After management and the board approve the RAS, management should communicate it to all employees. This is because everyone plays a role in risk management and should understand the organization's overall risk appetite and tolerances. This communication should define risk ownership as well as the roles and responsibilities for implementing the RAS framework. (See “Roles and Responsibilities” for details.)

Step 8: Review and Update Current Business Plans and Risk Policies

Ideally, the RAS would be closely aligned with the development of business plans and risk policies. The business world is dynamic and fluid, and the RAS must be responsive to significant changes in the competitive environment, regulatory guidance, risk-adjusted return opportunities, and the organization's risk profile and risk capacity. As such, the RAS, business plans, and risk policies should be “living documents” that are regularly reviewed and updated given key changes in the organization's business environment.

Step 9: Provide Ongoing Monitoring and Reporting

In order for the board and executive management to provide effective governance and oversight of the RAS framework, including the key risk exposures and concentrations of the organization, the ERM team must establish risk dashboard reports and monitoring processes. (See “Monitoring and Reporting” below for an example of an RAS dashboard report.)

Step 10: Provide Annual Review and Continuous Improvement

In addition to off-cycle reviews that ensure the company's risk appetite is responsive to significant changes in the business environment, the company should conduct a formal review of the RAS at least once a year. This formal annual review includes proposed changes to the RAS framework and risk tolerance levels, alignment with business plans and risk policies, and management and board approvals.

Moreover, the organization should look for opportunities to improve the RAS framework on a continuous basis. These enhancements may include economic capital models, stress-testing and scenario analysis, technology solutions and reporting tools, broader coverage of risk, exception management plans, and integration into strategic and business decisions.

ROLES AND RESPONSIBILITIES

The process of developing, implementing, and renewing a comprehensive RAS framework should involve key stakeholders from every level of the organization. Figure 12.3 provides a summary of the main roles and responsibilities for the business units, executive management, and the board. The RAS itself should document specific roles and responsibilities for carrying out the risk policy, including reporting and exception-management processes.

FIGURE 12.3 Key Roles

The “three lines of defense” model described in Chapter 8 offers a lens through which to view the risk governance structure and roles defined in the RAS:

- Business units (first line of defense) are ultimately responsible for measuring and managing the underlying risks in their area of business (i.e., profit centers) or functional units (i.e., support functions such as HR or IT). In effect, they are the “risk owners.” Business units represent the first line of defense because they are closest to risk acceptance and mitigation activities. They also have first-hand knowledge and experience in managing the risks that they face, including potential business impacts.

As active participants in the workshop meetings discussed previously in Step 3, the business and functional leaders are also responsible for defining their strategies and aligning them with the appropriate risk appetite and tolerance levels. Once the RAS is established, they must report policy exceptions to the CRO and/or executive management. The business and functional units are ultimately accountable for how well their businesses and operations perform vis-à-vis the risk tolerances established in the RAS.

- Executive management with the support of risk and compliance functions (second line of defense) is responsible for developing and communicating the RAS framework. The CRO (or equivalent) should lead this effort. The CEO, with the support of the executive management team, establishes the overall corporate strategy and ensures that business-unit strategies are aligned. Executive management is also responsible for defining the risk appetite and risk tolerances at the enterprise level and providing ongoing reporting to the board and other key stakeholders (e.g., regulators, rating agencies, institutional investors).

The CRO and the ERM team are responsible for developing analytical and reporting tools to measure and monitor aggregate risk exposures against risk tolerances. They also must provide business context, expert analyses, and root causes for any risk tolerance breaches. Executive management is ultimately accountable for how well it optimizes the risk/return profile of the organization and for the strength of its risk culture.

- The board with the support of internal audit (third line of defense) is responsible for reviewing, challenging, and approving the RAS framework. Once the framework is in place, the role of the board shifts to providing independent oversight. The risk or audit committee may take the lead in this ongoing process. It is also the responsibility of the risk or audit committee to step in when it sees exposures that are consistently above risk tolerances or if a business or functional unit does not demonstrate a strong risk culture. These failures may require a “deep dive” to investigate and correct. On the other hand, if risk limits and tolerances are never exceeded (i.e., no policy exceptions over an extended period of time), then the board may reasonably question whether the RAS tolerances are too high or lax to be effective.

The board is ultimately responsible for ensuring that an effective ERM program is in place, including a robust RAS framework. To fulfill this critical fiduciary responsibility, the board must receive timely, concise, and effective risk reporting from management, usually in the form of an RAS dashboard. This dashboard should clearly highlight any risk metric that falls outside its associated tolerance (e.g., by showing it in a “red zone”) and include commentary that explains the root causes for the policy exception along with management's plans and timeframe for remediation. We'll give a fuller introduction to the RAS dashboard below, with a complete discussion to follow in Chapter 19.

MONITORING AND REPORTING

The venue and timeframe for RAS monitoring will vary based on the business, function, and organizational level. For example, IT may monitor tactical risk metrics and warnings on a real-time basis in its data center “war room” where performance and risk indicators are displayed across multiple interactive screens. A business unit, and the ERM function, may monitor key business and risk metrics on a weekly basis, with more formal monthly or quarterly reviews. Executive management and the board would monitor the RAS based on their committee schedules.

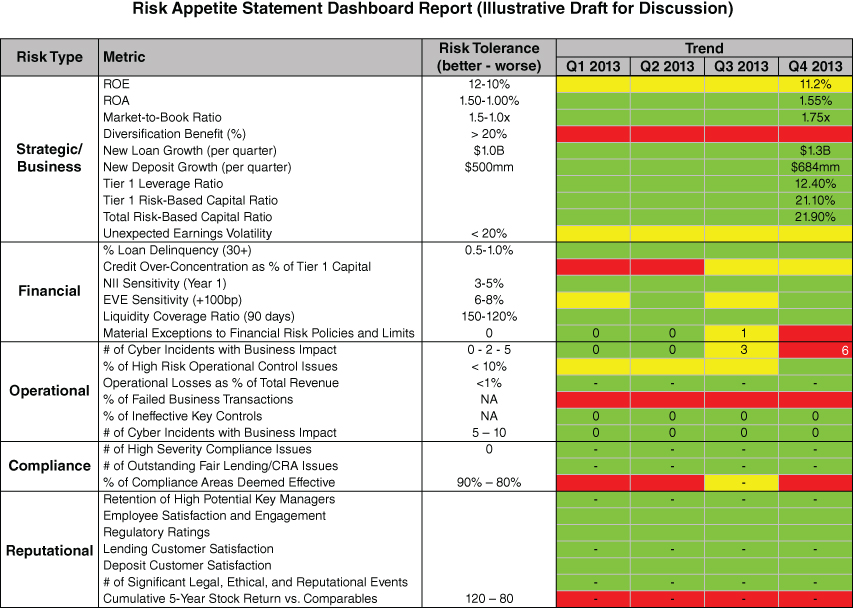

An effective RAS dashboard reporting process should be structured to produce consistent reports at various levels of the organization. Bear in mind that the number and types of metrics would likely vary with the target audience. Figure 12.4 provides an illustrative example of an RAS dashboard reporting structure. The report is organized into five primary risk categories: strategic/business, financial, operational, compliance, and reputational. Each risk category has a set of risk metrics assigned with tolerances or ranges that act as limits or guidelines for acceptable risk exposures. In this example, these metrics are tracked over the previous four quarters.

FIGURE 12.4 Risk Appetite Structure

Figure 12.5 shows an illustrative RAS dashboard report with specific metrics and tolerance levels for each major risk type. It is important to note that the RAS is meant to capture only the most critical risks. Otherwise, it would be far too unwieldy to be effective. By pinpointing the most useful risk metrics, the RAS aims to provide an overall, holistic view of the company's risk profile. For instance, it should identify key risk indicators (KRIs) that link to the main drivers of short- and long-term performance. These KRIs can alert management to the potential for unacceptable business outcomes and trigger corrective actions.

FIGURE 12.5 Risk Appetite Structure, Key Metrics

As an alternative or complement, the RAS metrics can be organized into separate reports by major risk type. This way, the risk executive responsible for that area can provide business context and expert commentary along with the RAS metrics. This reporting structure integrates qualitative and quantitative information, as well as allows for a greater number of RAS metrics.

An effective RAS should provide a “cascading” structure of risk exposures and limits at the board, executive-management, and business-unit levels. This structure allows users to drill down to underlying exposures to answer specific questions and issues (e.g., “What business activities make up our strategic risk exposure to China?”). Similarly, it aggregates business-level exposures upward to the enterprise level (e.g., “What is our total net credit exposure to Goldman Sachs across the entire enterprise?”). The level of detail visible for each metric depends on the needs of the specific audience (i.e., board, corporate management, or business unit). Figure 12.6 provides an illustration of cascading risk appetite statements at the three levels of the organization. As shown, the RAS would be at its most dynamic at the business level, where managers may choose to make changes based on risk/return opportunities while respecting board- and management-level risk tolerances.

FIGURE 12.6 Cascading and Dynamic RASs

Certain types of risk metrics will naturally aggregate across the organization while others are unique to specific business and operational units. Since the board and executive management RAS reports are focused on strategic and enterprise-wide risks, they should focus on aggregate risk metrics, such as:

- Earnings, including earnings-at-risk and unexpected earnings variance.

- Value, including shareholder value-added and market/book ratios.

- Loss, such as actual losses, operational loss-to-revenue ratios, stress-testing, or scenario-based losses.

- Cash flow, such as cash-flow-at-risk and liquidity-coverage ratios.

- Financial risk, including aggregate market risk and credit/counterparty risk exposures.

- Number of incidents, such as policy exceptions, cyberattacks with material business impact, and legal and regulatory issues.

- Key stakeholder metrics, such as retention of high-performance employees or levels of customer engagement and satisfaction.

Finally, the RAS should provide a “common language” for the ERM program. This would consist of a glossary of relevant business or technical terms and acronyms as well as a data dictionary that describes each risk metric, how it is calculated, where the underlying data is generated, and why it is included.

Examples of Risk Appetite Statements and Metrics

The following sections provide examples of risk appetite statements, performance and risk metrics, and risk tolerance levels for the following risk categories: enterprise-wide risk, strategic risk, financial risk, operational risk, legal/compliance risk, and reputational risk. For simplicity, each risk appetite statement is paired with one or two example metric(s) and risk tolerance level(s). In practice, there may be a number of risk metrics and risk tolerances for each risk appetite statement.

Enterprise-Wide Risk Management

The objective of our ERM program is to minimize unexpected earnings volatility and maximize shareholder value. The following risk appetite statements, metrics, and risk tolerances are in support of this overarching objective:

- Business Objectives: We will integrate our ERM program into our business decision-making, and design our risk-mitigation and management strategies to enhance the likelihood of achieving our business objectives. Metric: Any shortfall between actual vs. expected performance of our top strategic objectives will be less than 10%.

- Investment-Grade Debt Rating: We will maintain our capital adequacy and debt coverage to achieve an investment-grade rating from all major rating agencies. Moreover, we will maintain surplus capital and liquidity reserves to support future growth and buffer against economic uncertainties. Metric: Debt ratings from the major rating agencies will be at least investment grade; surplus capital and liquidity will exceed 15% of total requirements.

- Unexpected Earnings Volatility: We will perform earnings-at-risk (ex-ante) and earnings attribution (ex-post) analyses and target unexpected earnings variance to be a reasonable portion of total earnings variance. Metric: Monthly unexpected earnings variance (i.e., earnings variances from unexpected sources) will be less than 20% of total earnings variance.

- ERM Maturity: We will continue to develop our ERM capabilities to ensure that our program remains best-in-class. Based on the size and complexity of our business, we will achieve an “excellent ERM” assessment from independent third parties within three years. Metric: Completion of the three-year ERM roadmap initiatives and milestones will be at least 90% in the monthly tracking report.

- Risk Culture. All employees are expected to understand the risks associated with the business activities in which they are engaged. Every employee is accountable for operating within risk appetite standards and tolerances. Metric: Annual risk culture surveys will exceed defined target levels.

Strategic Risk Management

We strive to diversify our business portfolio to mitigate exposures to macroeconomic changes. Our business units will only pursue investment opportunities and business transactions that are consistent with the overall corporate strategy and our defined core competencies. We will focus our marketing efforts and technology initiatives to enhance significantly customer experience.

- Corporate Diversification: Our growth strategies (organic growth and M&A) will be formulated to create economic value and diversification benefit. Metric: Diversification benefit will exceed 30%.9

- Strategic Alignment and Core Competence Focus: We will focus on business investments that are consistent with our overall strategy and core competencies. Metric: Investment capital to support noncore businesses will be less than 10%.

- Customer Experience: We strive to offer a superior customer experience both online and in service centers. Metric: Customer satisfaction will exceed 80% in both channels.

- Risk-Adjusted Profitability: We will achieve an overall risk-adjusted return on capital (RAROC) that exceeds our cost of equity capital (Ke), resulting in a positive economic profit for the aggregate business and our shareholders. Metric: Enterprise RAROC will exceed Ke by at least 2%.

Financial Risk Management

We take financial risks in order to support our core business activities. We cannot predict the direction of financial markets and therefore do not speculate on markets to generate income. We manage our liquidity position in a conservative manner for both expected and stressed business conditions.

- Interest Rate Risk: Our treasury department aims to manage interest rate risk within board-approved limits. Metric: Maximum impact on income given a 100bp parallel shift in rates is 7%.

- Credit Risk: Our lending activities are based on strong underwriting standards and “know your customer” principles. Metric: Net credit losses will be less than 1% of average loan balances.

- Liquidity Risk: We manage our liquidity position to ensure that we can meet our cash obligations even under liquidity stress tests. Metric: Maintain a liquidity coverage ratio of at least 200% under the likely scenario and at least 110% under the stressed scenario.

- Hedging Effectiveness: We use derivatives for hedging purposes and never to speculate. We use only permitted derivative products, and each hedge transaction must decrease the earnings sensitivity of the overall risk position. Metric: Hedge effectiveness ratio will exceed 80%.

Operational Risk Management

We establish and test internal control systems to prevent, detect, and mitigate operational risk exposures. Each business unit is required to identify and assess its operational risks and ensure that they are measured and managed effectively.

- Operational Losses: We measure and track operational losses and incidents across the organization to identify root causes, mitigate risks, and ensure that losses are within acceptable levels. Metric: Operational loss/revenue ratios should be less than 1% for all business units.

- Talent Management: We strive to establish and maintain a talented workforce, especially through the professional development and retention of high-potential employees. Metric: Retention rate of high-potential employees will be at least 90%.

- Third-Party Vendor Management: We rely on business partners and third-party vendors to provide critical services. For that reason, we seek to minimize high-risk third-party vendor relationships. Metric: High-risk third-party vendor relationships must be exited within one year, or a viable, fully tested contingency plan must be in place.

- IT/Cyber-Risk. We manage our IT infrastructure to ensure system availability and capacity to meet business requirements as well as to protect against natural and manmade threats, including cyberattacks. Metric: Number of IT events with material business impact will not exceed two per month. Recovery time for critical-system failures will be within one hour. Automated patching program should exceed 90% of known vulnerabilities.

Legal/Compliance Risk Management

We will conduct our business within the confines of all laws and regulations. Every employee is held accountable for maintaining the highest ethical standards.

- Ethics Policy: We have zero tolerance for violations of our corporate ethics policy. We will respond to all exceptions to our corporate ethics policy based on the severity of the violation, including termination, bonus clawback, and legal actions. Metric: An action plan will be established for all significant ethical violations within 30 days.

- Open Regulatory Findings: The number of open regulatory findings will be maintained within an acceptable level. Metric: Active regulatory findings will be fewer than 15.

- New Legal Matters Opened: The number of new legal matters opened will be maintained within an acceptable level. Metric: New legal matters opened each month will be fewer than five.

- Legal and Compliance Cost: We will control the direct cost for resolving legal and compliance issues, including fines, settlements, penalties, and outside legal and regulatory advisory expenses. Metric: Total legal and compliance cost in the last 12 months will be less than $10 million.

Reputational Risk Management

Our reputation is extremely valuable, and it is every employee's responsibility to safeguard and enhance it. The board, CEO, and senior management will ensure that the level of reputational risk the company assumes is managed effectively.

- Customer Perspective: We will enhance our customers' experience when doing business with us and address any issues in a timely and effective manner. Metric: Acknowledge customer complaints within 24 hours, and resolve legitimate complaints within five business days.

- Employee Perspective: We will strive to be the employer of choice in our industry and maintain a high level of employee satisfaction. Metric: Annual survey of employee satisfaction will be greater than 90%.

- Shareholder Perspective: We will deliver superior shareholder returns and create significant shareholder value by allocating capital to the highest risk-adjusted return opportunities. Metric: Stock performance will be in the top quintile against our peer group.

- General Public and Media Coverage. We will closely follow coverage of our company in the press, social media, and other public forums to monitor reputational risk levels. Metric: We have zero tolerance for headline risk associated with unacceptable business practices, privacy breaches, and internal fraud.

The risk appetite statement is a foundational component of an effective ERM program. It establishes a board-approved policy that aligns the organization's risk tolerances with strategic objectives, risk profile, and risk-management capabilities. For the board, executive management, and business and operational staff, the RAS addresses a central question: “How much risk are we willing to accept to pursue our business objectives?” A risk appetite framework defines what key types of risk a company faces and sets tolerance levels to serve as guides and limits for decision-making at every level. To develop an RAS, a company must begin by assessing regulatory requirements before developing and socializing a prototype, obtaining management and board approval, and finally communicating the policy throughout the organization. A well-developed RAS framework will have a cascading structure based on the three lines of defense (business unit, management, board) so that each organizational level understands its responsibility and so that risks can be properly aggregated across the company.

The only thing certain in business is uncertainty. The RAS is an essential tool for any organization that strives to pursue its business strategy while managing all of its significant risks. By establishing strategic priorities and risk boundaries for all employees, a robust RAS that is communicated effectively can also have a profound impact on an organization's risk culture.