CHAPTER 14

Teaching Sign Language to Chimpanzees

How do the principles of ethology and experimental design in this book apply to learning outside of the conditioning chamber? From the point of view of the teacher or the trainer, does it really matter whether a teaching and training technique depends on feed forward or feed backward, on operant conditioning or Pavlovian conditioning, or even on errors in experimental design? The result is the same—or is it? Everything depends on what the teacher aims to teach. If the target behavior resembles obligatory responses evoked by food, then rewarding a hungry learner with food will work as it does in the Skinner box. Otherwise, food will favor the obligatory responses over the target behavior regardless of positive or negative consequences. In that case, the evidence reviewed throughout this book shows that the more rigorous the contingency the poorer the performance. Learners will often appear to be avoiding reward and seeking pain.

Suppose that the learner is a well-fed, free-living being, such as a human child or an infant chimpanzee that is living in a human home like a human child. Suppose that the target behavior is quite unlike lever-pressing or object discrimination, something complex like a human language. What then? We, Allen and Beatrix Gardner, found ourselves in just this situation when we began our sign language studies of chimpanzees.

Our objective was to compare infant chimpanzees with human children. This required a special sort of laboratory. Early in the 20th century, psychologists and biologists taught that all animals develop according to an inexorable species-specific plan. Provided with sufficient food, water, and shelter, each child should develop into a typical child, each chimpanzee into a typical chimpanzee, and so on. It was in those days that B. F. Skinner recommended a small, sterile, climatically controlled chamber as the best place to raise a human infant. Everyone hated Skinner for this proposal, but few questioned its scientific and practical merit.

To this day comparisons betweeen human children and other animals often overlook the contribution of behavioral environments. Experiments compare chimpanzees that live in cages—lucky if they have a rubber tire to play with or a rope to swing from—with children that live in the rich environment of suburban homes. In many so-called “developmental studies” of captive animals, the developmental variable is the number of years that the animal lived under deprived conditions. Most modern psychologists would expect human children to lose rather than develop intelligent behavior under comparable conditions. Indeed, older captives often score lower than younger captives at intelligent tasks (e.g., Tomasello, Davis-Dasilva, Camak, & Bard, 1987).

Experimental comparison requires comparable conditions. In our sign language studies, the chimpanzees had to live like human children. This rich environment provided a stringent test of traditional teaching methods. At about the same time, fresh ethological observations in the operant conditioning chamber revealed more and more flaws in the traditional view of the learning process. The new ethological studies combined with the patterns that we saw in our sign language studies led directly to this book. The next two chapters illustrate the patterns of success and failure and the novel adventures in teaching that tested the feed forward, ethological principles outlined in this book. We begin with a description of our cross-fostering laboratory.

CROSS-FOSTERING

On June 21, 1966, an infant chimpanzee arrived in our laboratory. We named her Washoe, for Washoe County, the home of the University of Nevada. To a casual observer Washoe’s new home may not have looked very much like a laboratory. In fact, it was the Gardner residence in the suburbs of Reno, originally purchased as a home for junior faculty, a small, one-story, brick and wood house with an attached garage and a largish garden in the back. To that same casual observer, Washoe’s daily life may not have looked much like laboratory routine, either. It was more like the daily life of human children of her age in the same suburban neighborhood.

Washoe was about 10 months old when she arrived in Reno, and almost as helpless as a human child of the same age. In the next few years she learned to drink from a cup and to eat at a table with forks and spoons. She also learned to set and clear the table and even to wash the dishes, in a childish way. She learned to dress and undress herself and she learned to use the toilet to the point where she seemed embarrassed when she could not find a toilet on an outing in the woods, eventually using a discarded coffee can that she found on a hike. She had the usual children’s toys and was particularly fond of dolls, kissing them, feeding them, and even bathing them. She was attracted to picture books and magazines almost from the first day and she would look through them by herself or with a friend who would name and explain the pictures and tell stories about them. The objects and activities that most attracted her were those that most engaged the grownups. She was fascinated by household tools, eventually acquiring a creditable level of skill with hammers and screwdrivers.

Washoe lived in a used house trailer, parked in a garden behind the house. With a few minor alterations, it was the same trailer that its previous owners had used as a traveling home. It had the same living-room and bedroom furniture and the same kitchen and toilet facilities. Someone came in to the trailer to check her each night and all through the night, every night, someone listened to her by means of an intercom connected to the Gardner home.

Ethologists use the procedure called cross-fostering to study the interaction between environmental and genetic factors by having parents of one genetic stock rear the young of a different genetic stock. It seems as if no form of behavior is so fundamental or so distinctively species-specific that it is not deeply sensitive to the effects of early experience. Ducklings, goslings, lambs, and many other young animals learn to follow the first moving object that they see, whether it is their own mother, a female of another species, or a shoebox. The mating calls of many birds are so species-specific that an ornithologist can identify them by their calls alone without seeing a single feather. Distinctive and species-specific as these calls may be, they, too, depend upon early experience (Slater & Williams, 1994; West, King, & Freeberg, 1997).

How about our own species? How much does our common humanity depend on our common human genetic heritage and how much on the equally species-specific character of a human childhood? The question is as traditional as the story of Romulus and Remus and so tantalizing that even alleged but unverified cases of human cross-fostering, such as the wolf children of India (Singh & Zingg, 1942) and the monkey boy of Burundi (Lane & Pillard, 1978), attract serious scholarly attention. An experimental case of a human infant cross-fostered by nonhuman parents would require an unlikely level of cooperation from both sets of parents. In a few cases, however, chimpanzees have been cross-fostered by human parents (Kellogg, 1968).

Cross-fostering a chimpanzee is very different from keeping one in a home as a pet. Many people keep pets in their homes. They may treat their pets very well, and they may love them dearly, but they do not treat them like children. True cross-fostering—treating the chimpanzee infant like a human child in all respects, in all living arrangements, 24 hours a day every day of the year—requires a rigorous experimental regime that has rarely been attempted.

SIBLING SPECIES

Chimpanzees are an obvious first choice for cross-fostering. They look and act remarkably like human beings and recent research reveals closer and deeper biological similarities of all kinds (Goodall, 1986). In blood chemistry, for example, the chimpanzee is not only the closest species to the human, but the chimpanzee is closer to the human than the chimpanzee is to the gorilla or to the orangutan (Ruvolo, 1994; Stanyon, Chiarelli, Gottlieb, & Patton, 1986).

For cross-fostering, the most important resemblance is that chimpanzees and humans mature very slowly. Infant chimpanzees are quite helpless: Adults must provide warmth, bodily care, and food (Plooij, 1984). The infants in our cross-fostering laboratory, Moja, Pili, Tatu, and Dar, only began to roll over by themselves when they were 4 to weeks old, to sit at 10 to 15 weeks, and to creep at 12 to 15 weeks. The change from milk teeth to adult dentition begins at about 5 years. Under natural conditions in Africa, infant chimpanzees depend on their mothers’ care almost completely until they are 2 or 3. They cannot survive if their mother dies before they are 3, even when older siblings attempt to care for them. Weaning only begins when they are between 4 and 5. In Africa, young chimpanzees usually live with their mothers until they are 7; and females often stay with their mothers until they are 10 or 11. Menarche occurs when wild females are 10 or 11, and their first infant is born when they are between 12 and 15 (Goodall, 1986, pp. 84–85, 443). Captive chimpanzees have remained vigorously alive, taking tests and solving experimental problems when they were more than 50 verified years old (Maple & Cone, 1981).

Under favorable conditions, their behavioral repertoire continues to expand and develop throughout their long childhood (Goodall, 1967; Hayes & Nissen, 1971; Plooij, 1984). This gives us a detailed scale of comparative development for measuring the progress of cross-fostered chimpanzees.

SIGN LANGUAGE

Perhaps the most prominent feature of a human childhood is the development of two-way communication in a natural human language. Without conversational give and take in a common language, cross-fostering conditions could hardly simulate the environment of a human infant. Before Project Washoe, the human foster parents spoke to their adopted chimpanzees as human parents speak to human children. In contrast to the close parallels in all other aspects of development, the chimpanzees acquired hardly any speech. For decades, the failure of a few cross-fostered chimpanzees to learn to speak supported the traditional doctrine of an absolute, unbridgeable discontinuity between human and nonhuman intelligence. There is another possibility: that speech is an inappropriate medium of communication for chimpanzees. In that case we must find a naturally occurring human language that does not require human speech. This was the innovation of Project Washoe. For the first time, the human foster family used a gestural rather than a vocal language.

American Sign Language (ASL) is the naturally occurring gestural language of the deaf in North America. Word-for-sign translation between English and ASL is about as difficult as word-for-word translation between English and any other spoken language. English has many common words and idiomatic expressions that can only be paraphrased in ASL, and ASL has its own complement of signs and idioms that can only be paraphrased in English. There are also radical differences in grammar. Where English relies heavily on word order, ASL is like the many other human languages that convey most of the same distinctions through inflection. Where English makes heavy use of auxiliary verbs such as the copula, to be, ASL is like the many other human languages that manage without the copula.

The signs of ASL, like the words of English, represent whole concepts. Finger spelling is based on a manual alphabet in which each letter of a written language is represented by a particular configuration of the fingers. It is a code in which messages of a written language can be spelled out in the air. Literate signers mix finger spelling with sign language as a way of referring to seldom-used proper names and technical terms, and we used finger spelling for this purpose in our laboratory. We also used finger spelling from time to time as a code to prevent understanding, the way human parents commonly spell out messages that they want to keep secret from their children. In general, we avoided finger spelling because our still-illiterate subjects could not understand or copy it, and also because too much finger spelling could easily lapse into manual English and defeat the objective of a good adult model of ASL.

Contrary to popular belief, ASL is not an artificial system recently invented by the hearing for use by the deaf. ASL existed in the United States more than 100 years before Project Washoe, and its roots in European sign languages can be traced back for hundreds of years (Stokoe, 1960, pp. 8–19). Outsiders have sometimes invented artificial gestural systems and taught them to their deaf clients. Within the deaf community, however, artificial sign languages have never competed successfully with the indigenous sign languages developed by the deaf, themselves, over the centuries.

Contrary to another popular belief, ASL does not consist of about 50 iconic gestures, understandable to all normal human beings. Instead, ASL is one of many, mutually unintelligible sign languages that have developed among the separate deaf communities around the world. International meetings of the deaf require simultaneous translators (R. A. Gardner & B. T. Gardner, 1989, pp. 56–57).

In ASL, new signs appear and old signs drop out, just as in spoken languages. Historically, the shapes of the signs of ASL have changed continuously, moving toward simplicity and smoothness of articulation in ways that parallel historical trends in the sounds of spoken languages. New signs appear as technical and social needs arise. Fluent signers tend to create the same new coinages for the same concepts, independently, and they tend to agree also on the relative appropriateness of suggested candidates for the same concepts (Kannapell, Hamilton, & Bornstein, 1969). This is what we would expect if there are structural rules for coining new signs.

Sign Language Only

Attempting to speak correct English while simultaneously signing correct ASL is about as difficult as attempting to speak correct English while simultaneously writing correct Russian. Often, teachers and other helping professionals who only learn to sign in order to communicate with deaf clients, attempt to speak and sign simultaneously. They soon find that they are speaking English sentences while adding the signs for a few of the key words in each sentence (Bonvillian, Nelson, & Charrow, 1976). When a native speaker of English practices ASL in this way, the effect is roughly the same as practicing Russian by speaking English sentences and saying some of the key words both in English and in Russian. It is obviously not a good way to master a foreign language.

It was clear from the start of Project Washoe, that the human foster family would provide a poor model of sign language if they spoke and signed at the same time. Signing to the infant chimpanzee and speaking English among ourselves would also be inappropriate. That would lower the status of signs to something suitable for nursery talk, only. In addition, Washoe would lose the opportunity to observe adult models of conversation, and the human newcomers to sign language would lose significant opportunities to practice and to learn from each other.

When the cross-fosterlings were present, all business, all casual conversation was in ASL. Everyone in the foster family had to be fluent enough to make themselves understood under the sometimes hectic conditions of life with these lively youngsters. There were occasional lapses in the rule of sign language only, as when outside workmen or the pediatrician entered the laboratory, but such lapses were brief and rare. Visits from nonsigners were strictly limited. Visitors from the deaf community who were fluent in ASL were always welcome.

The rule of sign language only required some of the isolation of a field expedition. We lived and worked with Washoe on that corner of suburban Reno as if at a lonely outpost in a hostile country. We were always avoiding people who might speak to Washoe. On outings in the woods, we were as stealthy and cautious as Indian scouts. On drives in town, we wove through traffic like undercover agents. We could stop at a Dairy Queen or a McDonald’s fast-food restaurant, but only if they had a secluded parking lot in the back. Then one of Washoe’s companions could buy the treats while another waited with her in the car. If Washoe was spotted, the car drove off to return later for the missing passenger and the treats, when the coast was clear.

Ethological Considerations

The exquisite development of the human vocal apparatus is matched by the evolution of peculiarly human vocal habits. Human beings are unusually noisy animals. There is a hubbub of voices at almost every social gathering, a great din at the most peaceful cocktail party or restaurant dining room. It is a mark of discipline and respect when an audience settles down in silence to listen to a single speaker. In the rest of the animal kingdom there are very few creatures—perhaps only whales and dolphins, and some birds—that make nearly so much vocal racket when they are otherwise undisturbed.

Chimpanzees are silent most of the time. A group of ten wild chimpanzees of assorted ages and sexes feeding peacefully in a fig tree at the Gombe stream in Africa may make so little sound that an inexperienced observer passing below can altogether fail to detect them. Since the time of the Tarzan films, chimpanzee movie stars have appeared to chatter incessantly on the screen. The effect is created by harassing the chimpanzees when they are off camera, and then dubbing their cries of distress onto the soundtrack. To those who are familiar with the natural vocal repertoire of chimpanzees the result is irritating and distracting. The distressed voice on the sound track clashes with the facial expressions and the postures on the screen, while it is easy to imagine the unpleasant scenes that evoked those high-pitched, nattering cries. When chimpanzees use their voices, they are usually too excited to engage in casual conversation. Their vocal habits, much more than the design of their vocal apparatus, keep them from learning to speak.

We confirmed these ethological considerations by comparing vocal and gestural behavior under controlled experimental conditions. In one experiment we used ASL to announce emotionally charged events to the cross-fostered chimpanzees, Tatu and Dar. Examples of positively charged events would be going outdoors to play or getting an ice-cream cone from the refrigerator. Examples of negatively charged events would be the departure of a favorite friend or the removal of a favorite toy. The key to this investigation was systematic presentation of planned announcements and events in a balanced experimental design during the course of normal daily activities in the cross-fostering laboratory. Tatu and Dar were more likely to sign than to vocalize under all conditions. But, there was more signing in response to the announcements than to the events that followed, while there was more vocalization in response to the events than to the signed announcements. The further from the exciting event the easier it was to evoke arbitrary gestural responses, and the closer to the source of excitement, the easier it was to evoke obligatory emotional cries (R. A. Gardner et al., 1989).

Because their vocalization is so closely tied to emotional excitement, attempts to teach chimpanzees to speak were probably doomed to failure, even under the most favorable conditions, as in the cross-fostering experiments before Project Washoe. As obvious as this may seem now, in those early days influential followers of B. F. Skinner still claimed that almost anything could be taught to almost any animal by the force of operant conditioning. The earlier research, particularly the 7-year, thoroughgoing, and highly professional, cross-fostering experiment of the Hayeses with Viki, was a necessary preliminary to Project Washoe. Before the definitive work of the Hayeses with Viki (see Hayes & Nissen, 1971), it would have been much more difficult to abandon spoken language in favor of sign language.

CHIMPANZEE SUBJECTS

Washoe was captured wild in Africa. She arrived in Reno on June 21, 1966, when she was about 10 months old and lived as a crossfosterling until October 1, 1970. In the next project, we started newborn chimpanzees at intervals to capitalize on the relationships between older and younger foster siblings. Moja, Pili, Tatu, and Dar, were born in American laboratories and each arrived within a few days of birth. Moja, a female, was born at the Laboratory for Experimental Medicine and Surgery in Primates, New York, on November 18, 1972, and arrived in our laboratory in Reno on the following day. Cross-fostering continued for Moja until late spring 1979. Pili, a male, was born at the Yerkes Regional Primate Research Center, Georgia, on October 30, 1973, and arrived in our laboratory on November 1, 1973. (Pili died of leukemia on October 20, 1975, so that his records cover only the first 2 years.) Tatu, a female, was born at the Institute for Primate Studies, Oklahoma, on December 30, 1975, and arrived in our laboratory on January 2, 1976. Dar, a male, was born at Albany Medical College, Holloman AFB, New Mexico, on August 2, 1976, and arrived in our laboratory on August 6, 1976. Cross-fostering continued for Tatu and Dar until May 1981.

TEACHING METHODS

In teaching sign language to Washoe, Moja, Pili, Tatu, and Dar we imitated human parents teaching young children in a human home. We called attention to everyday events and objects that might interest the young chimpanzees, for example, THAT CHAIR, SEE PRETTY BIRD, MY HAT. We asked probing questions to check on communication, and we always tried to answer questions and to comply with requests. We expanded on fragmentary utterances using the fragments to teach and to probe. We also followed the parents of deaf children by using an especially simple and repetitious register of ASL and by making signs on the youngsters’ bodies to capture their attention (Maestas y Moores, 1980; Marschark, 1993; Schlesinger & Meadow, 1972).

Washoe, Moja, Pili, Tatu, and Dar signed to friends and to strangers. They signed to themselves and to each other, to dogs, cats, toys, tools, even to trees. We did not have to tempt them with treats or ply them with questions to get them to sign to us. Most of the signing was initiated by the young chimpanzees rather than by the human adults. They commonly named objects and pictures of objects in situations in which we were unlikely to reward them.

When Washoe signed to herself in play, she was usually in a private place—high in a tree or alone in her bedroom before going to sleep. All of the cross-fosterlings signed to themselves when leafing through magazines and picture books, but only Washoe resisted our attempts to join in this activity. If we persisted in joining her or if we watched her too closely, she often abandoned the magazine or picked it up and moved away. Washoe not only named pictures to herself in this situation, she also corrected herself. In a typical example, she indicated a certain advertisement, signed THAT FOOD, then looked at her hand closely and changed the phrase to THAT DRINK, which was correct.

The cross-fosterlings also signed to themselves about their own ongoing or impending actions. We sometimes saw Washoe moving stealthily to a forbidden part of the garden signing QUIET to herself, or running pell-mell for the potty chair while signing HURRY.

Contrast With Operant Conditioning

The procedures of operant conditioning were plainly inappropriate. Withholding food or water or any other necessity, administering formal trial by trial training, paying the youngsters with treats for each sign or each sentence, all would have defeated the primary purpose of the cross-fostering laboratory. In fact, we found that most attempts at drill or bribery only interfered with the task at hand (see for example, B. T. Gardner & R. A. Gardner, 1971, pp. 123–140). Skinnerian methods failed whenever attempted with Washoe, Moja, Pili, Tatu, and Dar, just as they failed in other laboratories. The pattern of failure confirms the feed forward principles presented throughout this book.

It is, nevertheless, a tribute to the success of the cross-fostering studies that so many followers of B. F. Skinner have insisted that the results were “established in chimps through rigorous application of conditioning principles” (Schwartz, 1978, p. 374). We began early and explicitly to describe our departures from the prescriptions of operant behaviorism (B. T. Gardner & R. A. Gardner, 1971, pp. 123–140), but the extent of the departure seems to come out more clearly in films and tapes (e.g., R. A. Gardner & B. T. Gardner, 1973). A letter that we received from B. F. Skinner following a public television show, for example, attributes our positive results to operant conditioning and scolds us for our feed forward departures from his operant prescriptions:

I recently saw your Nova program and want to congratulate you. I have done enough of that sort of thing myself to know how difficult it is….

[However] I was quite unhappy about your new recruits—the young people working with the new chimps. They were not arranging effective contingencies of reinforcement. Indeed, they were treating the subjects very much like spoiled children. A first course in behavior modification might save a good deal of time and lead more directly to results. (B. F. Skinner, personal communication, May 24, 1974)

Eventually, a prominent student of B. F. Skinner fielded a rigorously operant version of Project Washoe, with the chimpanzee Nim (Terrace, 1979). This was carried to the point where research assistants were forbidden to treat Nim like a child (p. 118). They were even forbidden to comfort him if he cried out in the night (p. 71). Training sessions took place in a small room designed to simulate an operant conditioning chamber (p. 49). Mostly, training sessions consisted of demonstrating signs for Nim to imitate and showing him things to name, then rewarding correct responses promptly with the requested object or with some other treat (see Terrace, Petitto, Sanders, & Bever, 1980, pp. 377–378 for detailed descriptions). It is hardly surprising that videotape records of these training sessions showed Nim mostly imitating the trainer’s signs and begging for treats (Sanders, 1985; Terrace, 1979).

Terrace concluded that Nim lacked

the motivation needed to sign about things other than requests…. Can one instill a greater motivation to sign than we managed to instill in Nim? …

The ease with which a child learns language may be less a consequence of superior intellectual machinery than of a child’s willingness to inhibit its impulses to grab and to use words instead. In contrast to a child, a chimpanzee seems less disposed to inhibit its impulses, preferring to operate upon the world in a physical, as opposed to a verbal, manner. To get a chimpanzee into the habit of signing, it would help to begin instruction in sign language at an age at which its physical coordination is limited. During the chimpanzee’s first year, it is essentially as helpless as a human infant: its locomotion is rather limited, and it is quite uncoordinated in its attempts to grasp things…. While Nim was quite helpless, I should have required him to sign, or at least attempt to sign, for anything he wanted. (Terrace, 1979, p. 223)

From an ethological, feed forward point of view, however, it is easy to see that Nim grabbed so much because his trainers provided conditions that evoked grabbing rather than communication. Nim’s signs were usually requests because his trainers taught him to use signs for requests rather than for communication. The relentless application of extrinsic incentives evoked extrinsic responses that stifled communication. If Terrace had the opportunity to try the more extreme operant procedure that he describes in the quoted passage, he would only find, as the Brelands found, more “misbehavior” (chap. 8) and less communication. Human children are not born with some mysterious “willingness to inhibit impulses to grab”; they are, instead, reared in an environment that evokes communication rather than grabbing.

Approaching the problem in much the same way as Terrace, Rumbaugh and his associates taught the chimpanzee, Lana, to use a multiple-choice response panel to obtain a variety of goods and services (mostly foods and drinks) with strict Skinnerian schedules of reinforcement. “With regard to the intensity of training, it was decided that Lana would live in the language environment 24 hours a day. There, her linguistic expressions would provide repeated, reinforcing engagement with the system, since she would have to obtain all of her necessities and social interactions by making appropriate requests of it” (Gill & Rumbaugh, 1977, p. 158).

After this intensive overtraining, it was very difficult for Lana to transfer from one problem to the next. She often required extensive retraining to master simple variants of sequences of responses even though she had used the same responses correctly for tens of thousands of trials in other sequences (Gill & Rumbaugh, 1974). Overtraining, the hallmark of the Rumbaugh laboratory, had the negative effects on intelligent behavior we would expect from the evidence reviewed in chapter 13.

Later, Savage-Rumbaugh and her associates used a similar multiple-choice response panel with the chimpanzees Sherman and Austin. The second project concentrated on naming rather than pressing keys in specific sequences, and trainers handed rewards to the chimpanzees directly rather than relying on automatic dispensers. The greater social interaction between experimenters and chimpanzees and the relaxation of some of the operant rigor of reward delivery seemed to help Sherman and Austin. But the Rumbaughs taught Sherman and Austin to use the panel step by step according to the same Skinnerian model of language learning as before. Each step in the conditioning program consisted of a still more elaborate way to get food rewards (Savage-Rumbaugh, 1984, pp. 230–247).

Failure of Extrinsic Incentives

Lepper, Greene, and Nisbett (1973) studied the effect of extrinsic incentives on toddlers in a nursery school. Ordinarily, freehand drawing is a very popular activity in nursery school. Lepper et al. measured the amount of freehand drawing when they left toddlers by themselves with drawing materials. Next, the experimenters told half the children that they would reward them for drawing more and the more the drawing the more the reward. The other half were treated the same and received the same amount of reward, but the amount of reward was independent of the amount of drawing, and the experimenters never told the control children that rewards would depend on amount of drawing. The result was a dramatic decline in the amount of drawing by the contingent group. Extrinsic incentives actually suppressed the otherwise attractive activity of freehand drawing.

Freehand drawing is also a popular activity for young chimpanzees and extrinsic incentives have the same depressing effect on their art. In his study of a young captive named Congo, Morris (1962) made food contingent on freehand drawing and described his results as follows:

The outcome of this experiment was most revealing. The ape quickly learnt to associate drawing with getting the reward but as soon as this condition had been established the animal took less and less interest in the lines it was drawing. Any old scribble would do and then it would immediately hold out its hand for the reward. The careful attention the animal had paid previously to design, rhythm, balance and composition was gone and the worst kind of commercial art was born! (pp. 158–159)

To take an example that is directly relevant to communication, consider Hayes and Nissen’s (1971) report of the cross-fostered chimpanzee Viki:

… one hot summer day [Viki] brought a magazine illustration of a glass of iced tea to a human friend. Tapping it, she said “Cup! Cup!” and ran to the refrigerator, pulling him along with her. It occurred to us that pictures might be used to signify needs more explicitly than words….

A set of cards was prepared showing magazine illustrations in natural color of those things she solicited most frequently. [For 4 days Viki consistently used the picture-cards for requests, but on the 5th day] … suddenly she acted as if imposed upon. She had to be coaxed to cooperate and then used the pictures in a completely random way.

[After 7 months of erratic performance] … the technique which had seemed so promising was dropped, pending revision. Spring weather, plus a new car, gave Viki a wanderlust so that no matter what situation sent her to the picture-communication pack, when she came upon a car picture she made happy noises and prepared to go for a ride. We eliminated all car pictures from the pack, but it was too late. Long afterwards Viki was tearing pictures of automobiles from magazines and offering them as tickets for rides. (pp. 107–108)

Viewed from this perspective, the positive results of the cross-fostering studies with Washoe, Moja, Pili, Tatu, and Dar and the disappointing results of the operant conditioning studies that followed in other laboratories should be easier to understand. Terrace (1979) in his studies of Nim, Rumbaugh and his associates (see Gill & Rumbaugh, 1977) in their studies of Lana, and Savage-Rumbaugh (1984) in her studies of Sherman and Austin, all insisted on operant rigor in their laboratories and all obtained relatively negative results.

Modern psychobiologists recognize many primary motives rather than a few basic ones, such as hunger and thirst. Other motives, such as contact comfort (chap. 9), can be more powerful determinants of behavior than hunger and thirst. Human children learn to speak as if they were born with a powerful motive to communicate; extrinsic incentives are unnecessary. Many other animals behave as if they, too, were born with a powerful motive to communicate. Contact comfort and communication have obvious selective advantages, and the existence of many such basic motives is clearly more compatible with Darwinism than the elaborate process of conditioning based on hunger and thirst so often proposed in traditional theories.

There are important lessons to be learned here for those who teach children with special speech and language problems. There is much to be gained by assuming a motive to communicate and much to be lost by imposing ethologically irrelevant, extrinsic incentives (see also F. Levine & Fasnacht, 1974).

USES OF THE SIGNS

When teaching a new sign, we usually began with a particular exemplar—a particular toy for BALL, a particular shoe for SHOE. At first, especially with very young subjects, there would be very few balls and very few shoes. Early in Project Washoe we worried that the signs might become too closely associated with their initial referents. It turned out that this was no more a problem for Washoe or for any of the other cross-fosterlings than it is for human children. The chimpanzees easily transferred the signs they had learned for a few balls, shoes, flowers, or cats to the full range of the concepts wherever found and however represented, as if they divided the world into the same conceptual categories that human beings use.

The human members of the foster families observed the cross-fostered chimpanzees constantly throughout the day and attempted to record all of the significant activities of the day, but particularly the sign language and its verbal and nonverbal contexts. We grouped the signs of Washoe, Moja, Tatu, and Dar at 5 years of age into functional categories according the contexts in which they were used, such as names (DAR, ROGER), pronouns (ME, YOU), animates (BABY, DOG), inanimate objects (BALL, TREE), noun/verbs (BRUSH, DRINK), verbs (GO, OPEN), locatives (DOWN, OUT), colors (BLACK, RED), possessives (MINE, YOURS), material (GLASS, WOOD), numbers (ONE, TWO), comparatives (BIG, DIFFERENT), qualities (HOT, SWEET), markers (AGAIN, CAN’T), and traits (SORRY, GOOD).

Table 14.1 shows examples of context descriptions from the daily field records of Washoe, Moja, Tatu, and Dar grouped according to functional categories. For one representative sign from each category, Table 14.1 shows a summary description of contexts together with typical questions that evoked that sign and examples of verbal exchanges and phrases in which it appeared. Table 14.1 lists separately each of the signs in the category that we have called markers and traits, because these cases are both more complex and more significant. The examples and the summaries were all taken from the formal field records described in B. T. Gardner, R. A. Gardner, and Nichols (1989).

Functional categories such as those in Table 14.1 are called sentence constituents because they seem to serve constituent functions in the early fragmentary utterances of human children. One way to demonstrate the functional roles of these categories is to ask a series of questions about the same object. When Greg asked Washoe a series of questions about her red boot, her reply to WHAT THAT? was SHOE, to WHAT COLOR THAT? was RED, and to WHOSE THAT? was MINE. Replies to questions can establish the functional character of lexical categories. At the time of this example (filmed in R. A. Gardner & B. T. Gardner, 1973), Washoe had four color signs in her vocabulary: RED, GREEN, WHITE, and BLACK. If her only color sign had been RED, then all she would have had to do was to reply RED whenever anyone asked WHAT COLOR? With a group of color signs in the vocabulary, she could reply at different levels of correctness. If she had replied GREEN when asked WHAT COLOR THAT? of the red boot, it would have been an error, but a different sort of error from a reply such as SHOE or HAT or MINE. A reply can be functionally appropriate without being factually correct.

TABLE 14.1

Contexts and Uses of the Signs in the Vocabularies of Washoe, Moja, Tatu, and Dar at 5 Years of Age

R. Brown (1968) and others reviewed by Van Cantfort, B. T. Gardner, and R. A. Gardner (1989) used the replies of human children to WH questions of this sort to show that children use different functional categories of words as sentence constituents, even when the children are still so immature that they cannot frame WH questions on their own. Washoe, Moja, Tatu, and Dar also used appropriate sentence constituents in their replies to WH questions. As an additional parallel, longitudinal samples of the replies of the chimpanzees show the same developmental pattern that has been found in human children. Children and cross-fostered chimpanzees reply to WHAT questions with nominals and to WHERE questions with locatives before they reply to WHAT DO questions with verbs and to WHO questions with proper names and pronouns, while reliably appropriate replies to HOW questions appear even later (Van Cantfort et al., 1989).

PHRASES

As soon as Washoe had 8 or 10 signs in her vocabulary, she began to construct phrases of 2 or more signs. Before long, multiple-sign constructions were common. The last column of Table 14.1 shows typical examples of phrases. The individual terms within these phrases and sentences formed basic meaningful patterns such as agent-action (SUSAN BRUSH, YOU BLOW), action-object (CHASE DAR, OPEN BLANKET), action-location (GO UP, TICKLE THERE), possession (BIB MINE, HAT YOURS), nomination (THAT CAT, THAT SHOE), and recurrence (MORE COOKIE, MORE GO). Longer constructions could specify more than one agent of an action (YOU ME IN, YOU ME GREG GO), or specify agents, actions, and locations (YOU ME DRINK GO, YOU ME OUT SEE), or specify agents, actions, and objects of action (YOU GIVE GUM MOJA, YOU TICKLE ME WASHOE).

Table 14.1 may seem a little formidable at first, but we heartily recommend it as a realistic sample of the way sign language appeared in the casual conversations of the cross-fosterlings.

Word-for-Sign Translation

In our reports, the English glosses of ASL signs appear in captial letters and transcribe signed utterances into word-for-sign English. More liberal translations must add words and word endings that are without signed equivalents either in the vocabularies of the chimpanzees or in ASL. Literal word-for-sign transcription makes the utterances appear to be in a crude or pidgin dialect, but the reader should understand that equally literal word-for-word transcriptions between Russian or Japanese and English appear equally crude.

Creativity

Without deliberately teaching the chimpanzees to construct multiple-sign utterances, the human signers normally modeled simple phrases and sentences in their daily conversation. Washoe, Moja, Pili, Tatu, and Dar could all invent novel combinations for themselves. Washoe called her refrigerator the OPEN FOOD DRINK and her toilet the DIRTY GOOD even though her human companions referred to these as the COLD BOX and the POTTY CHAIR. When asked WHAT THAT? of assorted unnamed objects, Moja described a cigarette lighter as a METAL HOT, a Thermos flask as a METAL CUP DRINK COFFEE, and a glass of Alkaseltzer as a LISTEN DRINK (B. T. Gardner et al., 1989; R. A. Gardner & B. T. Gardner, 1991).

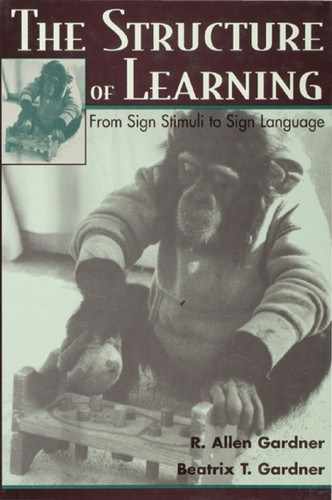

FIG. 14.1. Moja (30 months) at brunch with Allen and Beatrix Gardner. Moja is signing APPLE. Copyright © 1997 by R. Allen Gardner.

FIG. 14.2. Moja (33 months) signed TICKLE on (21-month-old) Pili’s hand, equivalent in a sign language to inflection for agent as in you/TICKLE/me (see Rimpau, Gardner, & Gardner, 1989). Pili affirms (see Gardner, Gardner, & Drumm, 1989) by signing TICKLE on his own hand. Copyright © 1997 by R. Allen Gardner.

In Oklahoma, Washoe frequently called the swans in the moat around her island WATER BIRD even though Roger Fouts called the swans DUCK. Fouts (1975) reported a systematic study of the chimpanzee Lucy in Oklahoma in which he asked Lucy to name a series of fruits and vegetables that no one had ever named for her in ASL. Among the objects that Lucy had to name for herself were radishes, which she called CRY HURT FOOD, and watermelon, which she called CANDY DRINK. Perhaps the clearest evidence that the chimpanzees learned signs as meaningful parts of meaningful phrases is the frequency and variety of new, chimpanzee-invented terms.

Development

Exciting as they are, first steps are only the beginning of walking and first words are only the beginning of talking. If the earliest utterances of human infants represent language, then they are best described as primitive, childish language. Gradually and piecemeal, but in an orderly sequence, the language of toddlers develops into the language of their parents. The well-documented record of human development provides a scale for measuring the progress of cross-fostered chimpanzees.

In a cross-fostering laboratory, the sign language of chimpanzees grows and develops. B. T. Gardner and R. A. Gardner (1994) studied the growth and development of phrases in the sign language of Moja, Tatu, and Dar, who were cross-fostered from birth for about 5 years. Size of vocabulary, appropriate use of sentence constituents, number of utterances, proportion of phrases, inflection, all grew robustly throughout 5 years of cross-fostering. The growth was patterned growth and the patterns were consistent across chimpanzees. Wherever there are comparable measurements, the patterns of growth for cross-fostered chimpanzees paralleled the characteristic patterns reported for human infants.

More advanced developments appeared with each succeeding year of cross-fostering. The proof that Moja, Tatu, and Dar had not yet reached any limit at 3 years is their growth during the 4th year, and the proof that they had not yet reached a limit at 4 years is the growth during the 5th year. Nevertheless, after 3 years of cross-fostering, they had clearly fallen behind human 3-year-olds, and they fell further behind after 4 years, and still further behind after 5 years. Chimpanzees should be even further behind human children after 6 years of cross-fostering, but by the same token, they should continue to advance and at 6 years they should be ahead of themselves at 5 years.

Sign language studies of cross-fostered chimpanzees reveal robust growth and development. Further intellectual development should continue until sexual maturity, which takes more than 12 years. Much more can be accomplished in future studies with long-term support.

MODULAR APPROACHES

Traditionally, comparative psychologists have analyzed language into theoretically defined components, such as concept formation or rules of order, and then studied each component separately. In this modular tradition scientists train, or attempt to train, nonhuman animals to perform arbitrary tasks that theory relates to hypothetical cognitive functions. Success at an experimentally isolated, concrete task is evidence that this or that nonhuman being possesses this or that abstract, cognitive function. The conclusions depend entirely on the theoretical reasoning that ties the task to the cognitive target.

In this modular spirit, Harlow used his learning set procedure (chap. 13) to train rhesus monkeys to solve oddity problems. In oddity problems the monkeys had to choose the correct object from among three alternatives. Presented with two circles and a triangle, the monkey had to choose the triangle. Presented with two green squares and one red square, the monkey had to choose the red square. Harlow (1958) argued that, “We would be very much surprised if there is any fundamental difference in the learning of the oddity problem and the learning of differential equations—other than that of complexity” (p. 288).

The success of Project Washoe stimulated modular studies of a variety of nonhuman animals (e.g., Herman, Richards, & Wolz, 1984; Matsuzawa, 1985; Pepperberg, 1990; Premack, 1971; Rumbaugh, 1977; Savage-Rumbaugh, 1984; Schusterman & Gisiner, 1988; Terrace et al., 1980), each study with its own theoretically defined components, highly specific tasks, and relentless application of operant conditioning. In modular studies, of course, it would be pointless to avoid operant conditioning or any other training techniques, regardless of how foreign these techniques would be in a human nursery. The entire performance usually consists of requests for goods and services or answers to questions with goods or services as reward.

Appropriately, the “symbol systems” of modular studies are usually synthetic and deliberately designed to be different from any naturally occurring human language. The more arbitrary the task, the stronger the argument that mastery depends on some abstract, cognitive function. In the typical “language-training” experiment, animals only have access to their apparatus-based symbols during formal testing sessions and formal tests usually represent the entire population of relevant responses. Conversation and communication are irrelevant. Comparisons with what human beings actually do or say are equally irrelevant. Growth and development is also irrelevant because investigators test only one module, or only one module at a time in an arbitrary sequence. The modular approach is very different from the developmental approach of cross-fostering.

Modular studies often make grand theoretical claims like Harlow’s claim about oddity problems and differential equations, but they are always claims about aptitudes and capacities. Both investigators and commentators find it easy to label them as studies of “ape language” or “animal language,” hence set apart from language proper.

Modular Semantics

In a typical modular study, Premack invented an artificial system of plastic tokens to test his chimpanzee Sarah. Figure 14.3 illustrates Premack’s “features analysis of apple” (Premack, 1971, pp. 224–226). At the top of Fig. 14.3, the object on the left represents an actual example of an apple and the object on the right represents the flat plastic token, colored blue and shaped like a triangle, that represented “apple” in Premack’s token language. The first pair of columns in the figure represent a series of tests in which Sarah had to choose between the following alternatives: (a) a red-colored patch versus a green-colored patch, (b) a round shape versus a square shape, (c) a square shape with a stemlike protuberance at the top versus a plain square shape, and finally, (d) a square shape with a stemlike protuberance at the top versus a round shape. The second pair of columns represents the choices that Sarah made when an actual apple was present, and the third pair of columns represents the choices that Sarah made when the apple object was removed and replaced by the apple token. She made the same choices for both, proving to Premack that the object and the token were equivalent for her.

FIG. 14.3. Features analysis of “apple” (after Premack, 1971). Copyright © 1997 by R. Allen Gardner.

What would happen if someone presented a 3-year-old human child with the same series of choices? In the experience of most toddlers only some apples are red. Apples also come in green, yellow, and many shades in between. Some apples are more than one color at the same time. Peeled or sliced apples are white until they sit for a while and become brownish. Apples also come in many shapes, particularly when cut up for eating. Only some apples have stems, and so on. Premack’s feature analysis of apple may appeal to traditional Aristotelian philosophers, but it has little to do with the experience of a human child or a cross-fostered chimpanzee growing up in a human world.

Outside of certain special laboratory conditions, the natural world resists Aristotelian attempts to divide it into true and false, red and nonred, apple and nonapple, fruit and nonfruit, and so on. For certain natural philosophers, this only means that the modular approach is more faithful to the underlying truths of philosophy. Yet the terms of natural languages mostly represent fuzzy categories that are faithful to the variegated, overlapping categories of the natural world (Zadeh & Kacprzyk, 1992). Moreover, human speakers and signers of natural languages use these fuzzy terms with great ease, beginning in infancy. This prominent characteristic of the human use of natural language is, perhaps, the clearest evidence that traditional Aristotelian logic is irrelevant to human language.

As early as 1923, Bertrand Russell said:

Let us consider the various ways in which common words are vague…. [Aristotle’s] law of the excluded middle is true when precise symbols are employed, but it is not true when symbols are vague, as, in fact, all symbols are. All words describing sensible qualities have the same kind of vagueness which belongs to the word ‘red’. This vagueness exists also, though in a lesser degree, in the quantitative words which science has tried hardest to make precise, such as metre or second…. (pp. 84–92)

Modular Conversation

Savage-Rumbaugh and her associates (Greenfield & Savage-Rumbaugh, 1990; Savage-Rumbaugh, McDonald, Sevcik, Hopkins, & Rubert, 1986) have made particularly strong claims for their modular studies of the bonobo, Kanzi. Bonobo is the common name of an animal that seemed at one time to be a pygmy variety of chimpanzee. Modern taxonomists distinguish two separate species, the bonobo (Pan paniscus) and the true chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes). Genetically and physiologically, bonobos are more specialized and further removed than chimpanzees from the main hominid line, though not so far removed as gorillas and orangutans (Stanyon et al., 1986).

Kanzi communicated with human beings by pointing at abstract forms displayed on a large response panel. Savage-Rumbaugh and her associates called these forms “lexigrams,” “words,” “elements,” and “symbols,” interchangeably. When Kanzi pointed at someone or touched someone present, this was transcribed as if he had pointed at a lexigram for “person.” Nearly all Kanzi’s lexigrams stand for different kinds of foods, drinks, destinations, or services (Savage-Rumbaugh et al., 1986, Table 1) in contrast to the varied vocabularies of Washoe, Moja, Tatu, and Dar (B. T. Gardner et al., 1989, Table 3.2).

Earlier work in the Rumbaugh laboratory with chimpanzees used a computer-assisted device that recorded all responses, automatically (Rumbaugh, Gill, & von Glasersfeld, 1973). Because the computer-assisted device became too cumbersome for use outside of a cage, it was mostly replaced by a folding panel with painted patches representing the array of lexigrams. When Kanzi moved from place to place, his trainers folded the response panel for portability and opened it up and spread it out again when they were ready to receive Kanzi’s next utterance.

Without automatic recording, records of Kanzi’s lexigram utterances depended on observer reports like the records of the signed utterances of Washoe, Moja, Pili, Tatu, and Dar. Like other serious investigators, Savage-Rumbaugh et al. (1986) saw that this procedure requires some evaluation of observer reliability. Accordingly, they videotaped a sample of Kanzi’s sessions with the response panel when he was in his 4th year. Independent transcriptions of the videotape agreed with the written reports of observers on the scene for 80% of individual lexigrams (Savage-Rumbaugh et al., 1986, p. 217).

When they were also 4 years old, very similar videotaped samples of Dar and Tatu yielded interobserver agreement of 84% and 81% for individual signs (R. A. Gardner & B. T. Gardner, 1994, pp. 217–218). This makes three comparable videotape records, two for cross-fostered chimpanzees using sign language, and one for a laboratory bonobo touching lexigrams on a panel. All three were made under comparable conditions with comparable interobserver reliability when the subjects were at comparable ages. In their taped records, Tatu averaged 441 signed utterances per hour and Dar averaged 479 signed utterances per hour. In his tapes Kanzi averaged 10.2 lexigram utterances per hour.

In Tatu’s tapes 35% of her utterances consisted of combinations of two or more signs, and in Dar’s tapes 49% of his utterances consisted of combinations of two or more signs. Savage-Rumbaugh has not yet published the proportion of phrases in Kanzi’s videotaped sample, but Greenfield and Savage-Rumbaugh (1990) described a sample of Kanzi’s utterances written down by observers on the scene when he was 60–69 months old. In this larger and later sample, Kanzi averaged 10.1 utterances per hour and 10.4% of these contained two or more elements.

There are several differences that could explain why Dar and Tatu were so much more fluent than Kanzi. First, bonobos are further removed from the hominid line than chimpanzees (Stanyon et al., 1986). Perhaps they have less aptitude for conversation. Second, the lexigram panel impedes the communication of any species. Greenfield and Savage-Rumbaugh (1990) report that Kanzi’s human trainers, themselves, “most frequently inserted only one or two lexigrams per sentence, reflecting the mechanical difficulty of the lexigram mode” (p. 568). Third, the laboratory regimen of modular training and testing, itself, probably depresses spontaneous communication.

A ROBUST PHENOMENON

In October 1970, after 51 months in Reno, when Washoe was about 5 years old, she went to the University of Oklahoma with Roger Fouts (R. S. Fouts & D. H. Fouts, 1989). In November 1972, we began a second venture in cross-fostering. The objectives were essentially the same, but there were several improvements in method. For example, Washoe was nearly 1 year old when she arrived in Reno. A newborn subject would have been more appropriate, but newborn chimpanzees are very scarce and none were offered to us at the time. After Project Washoe, it was easier for us to obtain newborn chimpanzees from laboratories.

Replication

For the scientific objectives of cross-fostering, the replication with Moja, Pili, Tatu, and Dar was essential to verify the original discoveries with Washoe. The second project also included many improvements over Project Washoe.

The chimpanzees of the second project interacted with each other and this, in itself, added a new dimension to the cross-fostering. In a human household, children help in the care of their younger siblings who, in their turn, learn a great deal from older siblings. Sibling relationships are also a common feature of the family life of wild chimpanzees. In the wild, older offspring stay with their mothers while their younger siblings are growing up and they share in the care of their little brothers and sisters. Close bonds are established among the older and younger members of the same family who remain allies for life. Equally significant for cross-fostering, the younger siblings follow and imitate their big sisters and big brothers (Goodall, 1986).

Seven-year-old Flint for example, followed and imitated his young adult brother, Faben, in a way that would certainly be described as hero worship if they had been human brothers. Faben was partially paralyzed as an aftereffect of polio and had a peculiar and striking way of supporting his lame arm with one foot while he scratched the lame arm with the good arm. During our 1971 visit to Gombe, we Gardners observed how Flint copied even this peculiar scratching posture of his brother Faben.

In order to capitalize on the relationships between older and younger foster siblings, we started them newborn, but at intervals, so that there would be age differences. Starting the subjects at intervals in this way also had the practical advantage of allowing us to add human participants to the project more gradually. In each family group, there was always a core of experienced human participants for the new recruits to consult as well as a stock of records and films to study. This helped us achieve the necessary stability and continuity in the foster families. Fifteen years after the start of Project Washoe there were still five human participants who had been long-term members of Washoe’s original foster family.

The second project became a fairly extensive enterprise by the time that there were three chimpanzee subjects. At that point, the laboratory moved from the original suburban home to a secluded site that used to be a guest ranch. The chimpanzees lived in the cabins that formerly housed ranch hands. Some members of the human families lived in the guest apartments and the rancher’s quarters. The human bedrooms were wired to intercoms in the chimpanzee cabins so that at least one human adult monitored each cross-fosterling throughout each night. There were great old trees and pastures, corrals and barns, to play in. There were also special rooms for observation and testing as well as office and shop facilities. The place was designed to keep the subjects under cross-fostering conditions until they were nearly grown up, perhaps long enough for them to begin to care for their own offspring.

Throughout the second project, several human members of the family were deaf themselves, or were the offspring of deaf parents. Others had already learned ASL and had used it extensively with members of the deaf community. With the deaf participants it was always sign language only, whether or not there were chimpanzees present. The native signers were the best models of ASL, for the human participants who were learning ASL as a second language as well as for the chimpanzees who were learning it as a first language. The native signers were also better observers because it was easier for them to recognize babyish forms of ASL. Along with their own fluency they had a background of experience with human infants who were learning their first signs of ASL.

Loulis

After she left Reno, Washoe continued to sign, not only to humans but to other chimpanzees whether or not there were any human beings in sight (R. S. Fouts & D. H. Fouts, 1989). This is more remarkable when we consider the procedure of Project Loulis. When Loulis was 10 months old he was adopted by 14-year-old Washoe, shortly after she lost her own newborn infant. To show that Washoe could teach signs to an infant without human intervention, Roger Fouts introduced a drastic procedure. All human signing was forbidden when Loulis was present. Because Loulis and Washoe were almost inseparable for the first few years, this meant that Washoe lost almost all her input from human signers. It was a deprivation procedure for Washoe. Later, Moja joined the group in Oklahoma, and still later Tatu and Dar joined the group in Ellensburg, Washington. The cross-fostered chimpanzees were allowed to sign to each other; indeed there was no way to stop them. They became part of Project Loulis.

Washoe taught signs to Loulis the way we taught her when she was an infant. During the first few days after Loulis arrived, Washoe often turned toward him signing COME, approaching him, and finally grasping his arm and drawing him close. During the next 5 days she signed COME and only approached without touching him. After about a week, Washoe only signed COME as she turned toward Loulis and faced him until he came to her. Washoe also molded Loulis’ hands to form signs. In one observation, as a human friend was bringing candy, Washoe repeated the FOOD sign, jiggling about and grunting with excitement. Loulis was watching her. Abruptly, Washoe stopped signing, molded Loulis’ hand into a FOOD sign and moved his molded hand to his lips. Washoe formed the GUM sign with her hands, but placed it on Loulis’ cheek. She also formed DRINK with her own hand and brought it to Loulis’ lips, and formed HAT with her own hands and brought it to Loulis’ head. In still another observation, Washoe placed a small chair in front of Loulis and repeated the CHAIR sign while watching him intently. Notice that Washoe always used feed forward rather than feed backward methods. Loulis learned more than 50 signs from the cross-fostered chimpanzees during the 5 years in which they were his only models and tutors. Meanwhile, Washoe, herself, learned some new signs from Moja, Tatu, and Dar (R. S. Fouts, D. H. Fouts, & Van Cantfort, 1989).

As Loulis grew older and moved freely by himself from room to room in the laboratory, there were more opportunities for the human beings to sign to the other chimpanzees when Loulis was not in sight. As expected, however, the rule against signing to Loulis had a generally negative effect on all human signing. There was little incentive for the research assistants to become fluent in ASL, and only a few of the most senior personnel acquired any signing facility. Thus, whether or not Loulis was in sight, there was little human signing to be seen in the laboratory. Human signing was almost completely withdrawn for 5 years.

Washoe, Moja, Tatu, and Dar continued to sign to each other and also attempted to engage human beings in conversation throughout the period of deprivation. The cross-fostered chimpanzees signed among themselves, even when there was no human being present and the conversations were recorded with remotely controlled cameras. Mainly the cross-fosterlings signed to each other about activities such as play, grooming, and moving together from room to room (R. S. Fouts & D. H. Fouts, 1989).

Once introduced and integrated into daily life, sign language was robust and self-supporting. The regimen that the Foutses enforced to demonstrate that the infant Loulis could learn signs from Washoe, Moja, Tatu, and Dar, was a drastic procedure for the cross-fosterlings. It slowed the growth of their sign language, but it proved that sign language, once acquired by cross-fostered chimpanzees, becomes a permanent and robust aspect of their behavior.