two

light and geography

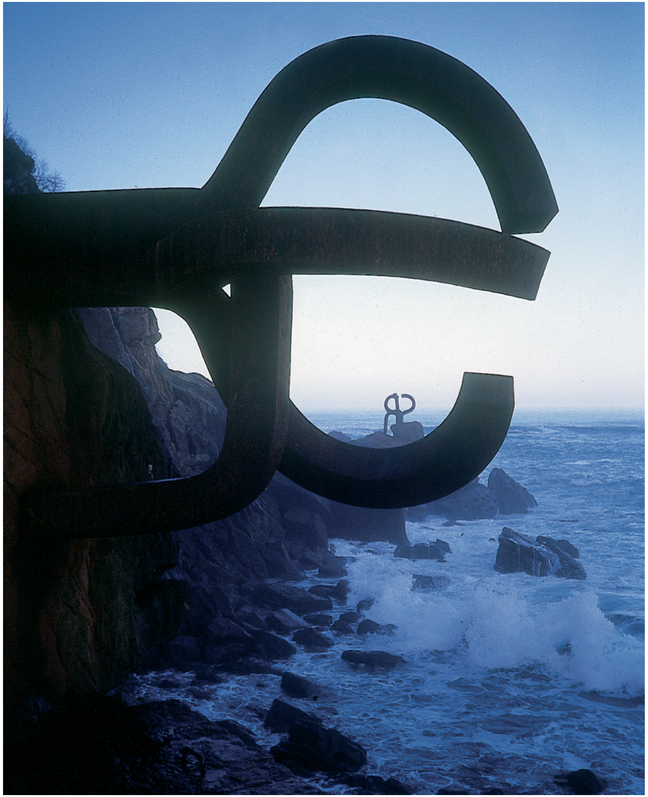

Opposite pagePeine de los vientos (The Wind Comb), sculpture, San Sebastián, 1977, by Eduardo Chillida.

Architecture and Orientation

From the Neolithic stone rings at Stonehenge on Wiltshire’s Salisbury Plain to the great pre-Columbian structures at Teotihuacán in Mexico, from the Temple of Amun-Ra at Karnak in Egypt to the 15th-century caves at Sacromonte in Spain, architecture has always been oriented around the light of the sun. The English words “orient” and “orientation” are, in fact, derived from the Latin for “east”. Traditionally, Christian churches were built facing east. In many cultures, east, where the sun rises, is the source of life; west, where the sun sets, symbolises all the terrors of death.

Natural light is the energy that makes life on Earth possible; it conditions life, and it is one of the main factors influencing architecture. This means that light is key to understanding what architecture should be – the “third skin”, outside our own skin and our layer of clothing, which protects us from the aggression of the world around us. In climates with excessive sunlight, houses can be built so as to contain a “pool” of controlled light, an inner courtyard or patio. At latitudes where natural light is insufficient, the fireplace becomes the centre of the house. Life flows around light as the Earth revolves around the sun.

Figure 2.1 The direction of the daylight is never perpendicular to the Earth’s surface giving the light a uniquely Nordic quality. Skylight, Dipoli Conference Centre, Espoo, Finland, 1966, by Reima and Raili Pietilä.

Nordic Light: Working with Reflection

As the Earth orbits the sun it tilts on its axis, giving rise to the various seasons of the year. That simple fact has a determining effect on life on earth. It also means that at the north and south poles the sun never sets during the summer, while it never rises above the horizon during the winter. In extreme northerly regions, survival depends on adapting to and managing this scarcity of natural light.

Life in Scandinavian countries is constantly overshadowed by the climate. For months, the sky is grey, and the land sleeps beneath a blanket of snow that hides every colour. Conversely, this same snow reflects the scarce winter light – a precious resource not to be wasted. The silence and inward reflection of these long months, during which time outdoors is reduced to a minimum, result in what we might term an “architecture of renunciation”.

In summer, the Nordic light varies in intensity. The direction of the daylight moves – although it is never perpendicular to the Earth’s surface, as when the sun “beats down” in hotter climes. Rather, the daylight slants down through the atmosphere, which acts as a concave lens. Dusk has a different quality: this could be expressed by saying that night “brushes” the horizon at a tangent but that total darkness never actually falls. The most aggressive light at these latitudes is experienced when the winter sun is shining almost horizontally – as will be clear to anyone who has ever driven westwards into a setting sun. Sunset in regions near the equator is sudden and quick, but in Scandinavia, and other northern regions, it can last for several hours. With respect to buildings, this particular light has to be treated with care: “captured”, measured out in doses, managed and tamed, before being brought into the domestic sphere.

The natural refuge for ancient peoples in these northern regions was the forest clearing and the fire. The great Danish architect Steen Eiler Rasmussen wrote: “a campfire on a dark night forms a cave of light, circumscribed by a wall of darkness. Those who are within the circle of light have the secure feeling of being together in the same room.”1 In such cases, the firelight alone generated the walls of Rasmussen’s “room”. Later in the history of the Nordic peoples, that “wall” would be built, materially, with structures enclosing the “clearing”. Here we can see the origin of Alvar Aalto’s experimental house on the island of Muuratsalo. The Finnish master’s description echoes that of Rasmussen:

Figure 2.2 The strength of Mediterranean light; vernacular architecture, Sagres.

The whole complex of buildings is dominated by the fire that burns at the centre of the patio and that, from the point of view of practicality and comfort, serves the same purpose as the campfire in a winter camp, where the glow from the fire and its reflections from the surrounding snow-banks create a pleasant, almost mystical feeling of warmth.2

In northern countries more than anywhere else, orientation towards sunlight is decisive for the shape of buildings. Architecture adapts like sunflowers rotating to follow the arc of brightest light. Skylights and high windows prevent the light from entering horizontally during long-drawn-out sunsets, diverting it so as to let it in at the convenience of occupants – as can be experienced at Sigurd Lewerentz’s St Peter’s Church in Klippan, western Sweden. Light comes in indirectly from skylights hidden in the artificial cloudy sky ceiling.

Lewerentz’s approach relies on a very precise way of managing light, one that demands technical expertise as well as familiarity with the effects of natural light. If architecture is to rise to the challenge of achieving precision, the architect needs to get to know nature so as to find in it the key to each location’s particular problems. Light in northern countries, like water in southern deserts, is a precious commodity to be treasured, measured out and worked on by a master hand.

Mediterranean Light: Drawing with Shadows

In Mediterranean countries, the situation is very different. Here, the constantly changing light confers unity on the diversity of cultures, languages, ethnicities and landscapes that make up the Mediterranean region – from the megaliths in Malta to the temples of Greece or the Arabic buildings in Morocco. Sunlight and sea provide a framework for the evocative Mediterranean myth of an eternal return to the past in the present. Here, more than ever, art works to the same rhythm as nature and builds forms that harmonise with it. Under such strong light, architecture becomes, in the words of author Benedetto Gravagnuolo, “pure Euclidean volumes, as symbolic expression of the arithmetic canons of ‘divine proportion’, as a shade of Apollonian beauty”.3

If there is indeed a cross-cultural Mediterranean tradition of dwelling places, then it is not connected with academic or “polite” architecture but with the vernacular; it is not driven by politics, ideology or religion, but is simply a way of positioning oneself beneath

Figure 2.3 Clear, ordered forms for the modern age: Villa Shodhan, Ahmedabad, India, by Le Corbusier.

the strong light. This is evident in its austere forms and pure, geometric shapes, defined by the sun that cuts along their sharp edges and by the shadows that outline them. In 1905, a trio of young and still unknown artists – Henri Matisse and André Derain, who had spent the summer painting in a little French fishing village on the Mediterranean called Collioure, and their friend Maurice de Vlaminck – discovered, as Vincent van Gogh had done years before them, that colours were heightened and became much brighter in contact with the strong luminosity of the Mediterranean sun. When they finished painting, they exhibited their canvases at the Salon d’Automne in the Grand Palais in Paris.

This marked the birth of fauvism as the fruit of an encounter with light. Along with that other vanguard of the 20th century, architectural modernism, fauvism had a desire to get to the essence of things, to discard everything superfluous. Central to both movements was a belief that an accumulation of details robs objects of their strength and truth, and makes them lose their essential reality. As these ideas developed they gave birth in turn to purism, a variant of cubism created by Le Corbusier and Ozenfant which proposed that art needed to reflect the ‘spirit of the age’, exclude emotionalism and expression and learn lessons inherent in the precision of machinery. It stripped back the detail, favouring a return to clear, ordered forms suitable for the modern age.

Le Corbusier’s magnificent definition of architecture as “the wise […] play of volumes under light” (le jeu, savant, correct et magnifique des volumes sous la lumière) sprang from both an experience of and an attitude towards light that saw forms as “playing” not with light but under it – meaning the strong, overarching light of the Mediterranean. The Swiss master added, in an address given to CIAM (the Congrès internationaux d’architecture moderne):

Le Corbusier’s discovery of the light of the Mediterranean in his 1911 travels across Turkey, the Balkans and southern Europe left a permanent mark on all his subsequent work. Everywhere on what he called his voyage utile (“useful journey”) he visited, he discovered this remarkable light, and from this experience he derived architectural motifs that would recur throughout his career. A defining note of his architecture, and an inescapable part of his legacy, is strong light throwing clear-cut shadows.

This Mediterranean light fits in with modern, purist architecture’s search for simplicity, harmony of volumes and functionality. The architecture that emerged at the beginning of the 20th century aimed to get rid of all gratuitous ornamentation and find beauty in sheer form, giving material expression to the essence of any design. This ideal is what Austrian designer and theorist Adolf Loos expressed in his writings from the time of his first journey to Italy in 1906. It is expressed in Italian architect Adalberto Libera’s Villa Malaparte on the island of Capri, and is apparent in the villa-studio for an artist presented by Luigi Figini and Gino Pollini at the Mostra dell’abitazione (Exhibition of Modern Housing and Living) of the Fifth Triennale in Milan in 1933. It also underlies Giuseppe Terragni’s Casa del Fascio in Como, and Alberto Campo Baeza’s light-filled impluvium at Granada.

The Baltic–Mediterranean Hinge

Italian architect Bruno Zevi, in his “materialist interpretations” of architecture, suggests a direct relationship between the light of a particular geographical region and that region’s architectural form. In southern climates the sun’s rays fall almost perpendicularly on the Earth’s surface, and so greater shadow contrasts are obtained with cornices and other horizontal projections on buildings. In northern countries, however, where the sun is lower and its rays more tangential to the Earth, vertical building elements are more effective at using light as an architectural instrument. Zevi commented further, in detail:

German art historian Wilhelm Worringer showed his understanding of this same point when, in his doctoral thesis, he traced a connection between the empathetic relationship of the Mediterranean regions with nature and their development of an art that was the exact opposite of the tormented anguish of the cloudy northern regions. Once again, it is light that dictates the “rules of the game” since it is light that is its ultimate cause.6

By virtue of its being “grounded”, architecture automatically belongs to the place in which it sits, and good architects are more influenced by the location for which they are designing than by their own cultural origins. Such designers, working in other countries with a different kind of light to their own, adapt their work to it. This may be observed in what could be called the “Baltic-Mediterranean hinge”, the mutual attraction felt by these two different cultures – like that of two magnetic poles. This special fascination has recurred throughout history: architects from the northern countries have gone to learn in the light of the Mediterranean, while the work of great Nordic masters like Alvar Aalto, Arne Jacobsen, Erik Gunnar Asplund and Jørn Utzon has had a notable influence on architects from the south. In all cases, the resulting works have displayed an adaptation to local conditions and have never been a simple transplanting of ideas.

In autumn 1913, Swedish modernist Erik Gunnar Asplund travelled south from Stockholm to study the sources of Mediterranean architectural culture, as Le Corbusier had a couple of years earlier. The lessons learned during Asplund’s six-month trip would stay with him for the rest of his life; the notebook that he wrote as he travelled abounds with remarks about light and colour. The luminous spaces and rooms surmounted by cupolas, which Asplund would later incorporate into his public buildings, are stamped with the classicism that he discovered on his journey “to the light”.

Figure 2.4 School of Science and Technology, Otaniemi, Finland, 1964, by Alvar Aalto.

School of Science and Technology, Otaniemi

Finnish architect Alvar Aalto was likewise deeply influenced by his journey to Greece in the 1950s. The theatre at Delphi, a model of open public space, is clearly echoed in his works such as the School of Science and Technology at Otaniemi, just outside Helsinki, where the amphitheatre trope is used twice over. Externally, the roof is the main focus of attention, emulating in form and function as a public space; internally the auditorium too is a powerful fixed point in the composition. The ordering and separation of the different parts in the overall arrangement of this building complex display great sensitivity to the landscape. But because of the Finnish climate, the open-air layout is covered over; the outdoor space becomes an internal one, but, thanks to Aalto’s genius, without robbing it of natural light.

Utzon's House at Porto Petro

Jørn Utzon worked with the Danish master Rasmussen at the Copenhagen Academy of Art. He subsequently travelled to Mexico, the Far East and North Africa, filling his notebooks with ideas and impressions as he went. Utzon drank in the southern light, and studied it as an architectural instrument for creating space. Of particular note in this regard is his house at Porto Petro, Mallorca. From the sea, the dwelling looks like just another ruin on the coastline – reminiscent, perhaps, of the Temple of Athena on the Acropolis of Athens. Stone slabs with the deliberate bareness of a ruined Greek shrine – unornamented, devoid even of timberwork – offer their lines to the movement of the sun and shadows. The layout of the linked buildings also recalls the Acropolis in its freedom of disposition, its integration into its natural surroundings and its appropriation of the terrain. Such architecture lies “outside time”: despite its southern setting, it gives the impression of renunciation and great silence. Here, Utzon adapted himself completely to the essence of the Mediterranean tradition: he understood the light, and built accordingly.

Stockholm Museum of Modern Art

Finally, we shall look at the other side of the “hinge”. A Spanish architect, Rafael Moneo, working in Stockholm, shows us how good architecture has the flexibility to adapt itself to the medium. The architecture belongs to the place, and the place is characterised by its particular light – in this case, the more solemn, northern variety; that is one of the essential elements for understanding the architectural approach taken here. In the case of Moneo’s Museum of Modern Art on the island of Skeppsholmen in Stockholm (1998), light becomes the key to resolving the question of space. The Swedish architectural

Figure 2.5 Light and shadow on the patio of Jørn Utzon’s house at Porto Petro, Mallorca.

tradition reflects the changing, irregular Scandinavian landscape, developing a special sensitivity towards subtly graded connections in close relationship with the quality of the northern light – a light that does not reveal a single, unified space as in southern countries, but a world made up of a multitude of different places. Consciously resisting the temptation of the monumental, Moneo offers a discontinuous, articulated architecture that respects its surroundings, and which is characterised by fragmentation and lightness of touch.

His solution is a compromise between southern rationality and northern organicism. The irregular profile created by the museum’s multiple roofs blends into its island setting (as, incidentally, does the winding outline drawn by the ceiling of the lecture room in Aalto’s 1935 library in Vyborg – now Russia – on the room’s glass outer wall). The rigorous quality of the Skeppsholmen project was the result of careful lighting and acoustic trials. Moneo spent a year measuring and defining the characteristics of the natural light, and the effect of this light on the interior of the rooms, and used this to determine the exact angle of each ceiling with regard to the skylights, which differ from one another by irregular degrees in the different rooms. His light testing was of fundamental importance in situating the works of art themselves. The skylights possess an intriguing ambivalence, being both picturesque architectural features and precision instruments.

Moneo’s response to the lighting problem – how to capture and maximise the northern light – uses the same traditional technique that Sir John Soane employed in his 1813 Dulwich Picture Gallery and in his own house in Lincoln’s Inn Fields (1824). The latter comprised an adaptation of the Roman domus (city dwelling) to the light of London, with a vestibule like an impluvium (sunken atrium floor) and Pompeiian frescoes in the dining room. Skylights are used to leave the maximum amount of wall space for displaying works of art, but Soane manipulated the direction taken by the light, “leading” it into the gallery and the adjoining mausoleum. It is similar to the experiments by baroque architects Filippo Juvarra and Gian Lorenzo Bernini in illuminating a main space through complex light chambers, introducing the light through the vaults of apses. The baroque architects had taken this idea in turn from Byzantine and late Roman architecture, creating genuine teatrini sacri (sacred theatres) by their management of light in secondary spaces. Aalto also used it in his celebrated church at Imatra, near the Finno–Russian border, and Moneo – as we have seen, in Stockholm – testimonies to the potency of light and geography in all great architecture.