Chapter 2

Realizing Business Benefits

It's about the business. That is the primary theme running throughout this book, and for program-oriented organizations, the realization of business benefits is the primary purpose of their program management discipline. In our own careers, we have witnessed the power of program management to serve as a coalescing function that focuses the various elements of an organization upon the achievement of its business goals and is the primary reason why we titled this book Program Management for Improved Business Results.

Many others seem to agree. The achievement of business benefits is the center of the program management guides and standards that have emerged and matured over the years, and has been a primary topic of writings from other authors. From our viewpoint, however, there needs to be additional distinction on what is now commonly referred to as business benefits in regard to program management. The business benefits that program management helps to deliver comprise two components: business value and business results. Business value encompasses the synergistic improvements that program management brings to optimize the business functions of an enterprise. Business results are the tangible business outcomes that result from the creation and delivery of new capabilities through the firm's programs.

In this chapter, we explore these two sides of business benefits realization through the implementation of program management within an enterprise.

Realizing Business Value

Benefits realization in the broad sense is closely tied to value management. Ray Venkataraman and Jeffrey Pinto described value management as “a management approach that focuses on motivating people, developing skills, and fostering synergies and innovation with the ultimate goal of optimizing the overall organizational performance.”1 In a sense, they are describing the value that program management brings to an organization, especially to those organizations that implement program management to its full capacity. In this case, business value is accomplished through the optimization of a firm's business functions in a number of ways, including:

- Aligning business strategy and execution

- Integrating business functions

- Navigating business and environmental ambiguity

- Achieving business scalability

- Managing distributed collaboration

- Reducing time-to-benefits

Aligning Business Strategy and Execution

Many organizations engage in yearly strategic planning activities that focus on identifying long-range business goals, as well as high-level plans on how to achieve them. Good strategic management practices identify what an organization wants to achieve (strategic goals) and how they will be achieved (strategies) over a specified time horizon, which is typically three to five years. For product companies, strategy consists primarily of a collection of product ideas that, when turned into tangible products, contribute to the achievement of the strategic business goals. For service-oriented companies, strategy consists of a set of services that collectively contribute to the achievement of the strategic goals, and for change initiatives, strategy consists of new organizational transformation and breakthrough capabilities that will help achieve company strategic goals.

As an organization begins to grow and scale its offerings, maintaining alignment between work output and strategic intent often becomes a challenge. In part this is due to the increased number of offerings in the pipeline, but also the increasing number of cross-organizational groups required to be involved, and in many cases, an increasing layer of middle management. Simply stated, the link between execution output and strategic goals begins to weaken, and in some firms may eventually break.

For many organizations, program management provides value to their business by serving as the organizational glue that can prevent the misalignment between execution and strategy. As detailed in the next chapter, program management creates a critical linkage across strategic goals, program objectives, and project deliverables focused on delivering the business benefits intended. In doing so, one can establish direct traceability between strategic goals, business success factors, and project performance measures.

Integrating Business Functions

Implementation of strategy involves many business functions and processes that need to be coordinated and integrated into synchronized business actions. Traditional project- or functional-oriented approaches possess some of this integration capability. However, they tend to be tactically focused on the triple constraints—time, cost, and scope—and many times fail to serve as the business integrator focused on the implementation of strategy.

Integration efforts require significant collaboration across multiple organizations and functions, which can be hampered by parochial behaviors within traditionally siloed functions. Compounding this problem is that many times, the management personnel involved in strategic planning, portfolio planning, and execution are different with limited overlap, which minimizes effective communication and collaboration. This results in ineffective business integration.

Program management adds business value by serving as the mechanism by which the work of the various operating functions within a company is integrated to create an effective business model. For example, consider the business functions of marketing, engineering, manufacturing, and finance. Each function has its own language and jargon. Marketing language talks about the four Ps (product, price, place, promotion), finance discusses discounted cash flow, engineering discusses technical performance, and manufacturing is interested in production yield and defect rates. To say that experts from different functions often do not understand one another, let alone often do not work well together, is an understatement.

The inclusion of program management in a firm's business model provides value to those organizations seeking to integrate the efforts of their business functions to achieve business results through the development and delivery of new capabilities or transformative change. When program management is properly defined and implemented, it helps to execute business strategies through the collective efforts of the business functions of an enterprise. Figure 2.1 illustrates this point.

Figure 2.1 Integrating business functions.

Program management integrates the collective efforts by focusing the various functions on a common purpose: achievement of improved business results. Even though they may speak in differing jargon, commonality is established through a collective purpose and goal. The integration of cross-organizational efforts increases the probability of successfully achieving the intended business results in a repeatable manner.

Navigating Business and Environmental Ambiguity

Management teams in successful and innovative companies fully understand that some of the greatest opportunities reside in the fuzzy front end of a program.2 The ability to accurately forecast future customer, user, and market needs and then integrate those needs with leading edge capabilities is critical for companies to survive in their respective industries.3 This work is never simple and high levels of ambiguity have served as a test in frustration and a lesson in patience for many.4

However, the presence of ambiguity is a characteristic of many capability development efforts, and the ability to manage it effectively can provide great business opportunity and competitive gain. Program management can provide business value for companies looking to successfully produce competitive capabilities on a consistent basis by providing the means to effectively navigate ambiguity and harness the innovation engines of their firms.

The key to realizing these opportunities is the ability to contain the fluid and ambiguous nature of a program. This can be accomplished by establishing a framework and well-defined targets to provide focus and by employing effective leadership to cut through the ambiguity and competing agendas of stakeholders that often characterize a program.5

Richard Vander Meer, Vice President of Global Program Management, described the role of program management in containing ambiguity at Frog:

I see program management as the backbone of the company. We have to maintain stability in the middle of a very creative and often chaotic design-driven environment. This involves establishing and maintaining integrity of work, ensuring financial responsibility, and providing stability for the team and the client.

Containing ambiguity through a framework involves creating a system of objectives that focus and motivate the efforts of the program team. The objectives must be both time- and business-focused. Time-focused targets consist of regularly scheduled review meetings with senior management to demonstrate continued convergence progress in the development of a capability concept. Business-focused targets include the relevant objectives that drive the need for the capability (for example, increased revenue, lower operating costs, or market transformation).

By employing program management principles to contain ambiguity, an organization will realize the following three key benefits: 1) the leadership necessary to effectively coalesce multiple perspectives and agendas; 2) a framework to enable flexible management of change; and 3) a business champion to ensure that the strategic goals set forth by senior management are achieved.

Achieving Business Scalability

As an organization grows, its ability to effectively scale its business processes and consistently deliver positive return on investment becomes increasingly challenging. The challenge normally falls upon the business manager charged with investing in new capabilities. When an organization is small, the business manager is able to manage both the investment in new capabilities as well as manage the return of the investment through the creation of new capabilities. When higher levels of growth occur, however, the business manager often finds that he or she is not able to perform both management functions as effectively as needed.

Program management offers business value by providing the organization a pathway to effectively scale the business by assuming the management of return on investment duties for the development of each new capability.

As illustrated in Figure 2.2, a business manager's ability to scale a business becomes constrained by his or her ability to personally scale. The addition of the program management discipline and skilled program managers removes this constraint and allows for business scalability.

Figure 2.2 Achieving scalability with program management.

The business manager still maintains total investment responsibilities for his or her business and for each program, as well as accountability for total return on investment. However, the business manager allocates portions of his or her investment to the various programs within the portfolio and to the program managers responsible for managing the investment through execution of a program. The program managers become accountable for delivering the return on investment (business results) for each of their respective programs. In effect the program manager serves as the business manager proxy.

A prerequisite for business scalability through program management, however, is the level of business acumen of the program managers. To achieve scalability, the business manager must be able to hand over the management of return on investment with confidence. Therefore, the program manager must possess the skills and competencies to fully manage the business aspects of a program (Chapter 11).

Managing Distributed Collaboration

Due to the amount of complexity required to meet customer and user demands for performance, features, and customized capabilities, today's work efforts are often beyond the scope of a single project.6

Effectiveness requires an integration of work efforts and outcomes to satisfy the growing complexity of business. However, another modern phenomenon—distributed teams—has added an additional layer of complexity and difficulty to the integration of multiple work outcomes.

The world is getting flatter. This is how Thomas L. Friedman, in his book titled The World Is Flat, describes the phenomenon that began in the 1990s and continues today, whereby knowledge work can be digitized, disaggregated, distributed, produced, and reassembled across the globe.7 The flattening of the world has enabled people in countries like China, Russia, India, and many others to participate in capability development efforts in the west. This has created a new business model where highly distributed collaboration is required.

However, many companies have historically operated under a traditional structure characterized by strong siloed departments or groups where horizontal collaboration across these departments is difficult, let alone collaboration across the globe. One by one these companies are realizing the need to adopt a distributed model not only to compete, but in many cases to survive.

Many companies that are succeeding in management in these increasingly distributed environments are doing two key things: 1) adopting a systems approach to developing their capabilities, and 2) adopting program management to effectively integrate their solutions. Early adopter companies in the automotive, aerospace, and defense industries continue to utilize this approach. More recently, companies such as Apple, salesforce.com, Intel, and Kaizer Permanente among others have found great success in utilizing systems and platform concepts coupled with program management to develop their new capabilities. Not surprisingly, these companies are consistently succeeding in the management of distributed efforts that employ outsourcing, open-sourcing, in-sourcing, and off-shoring techniques.

Reducing Time-to-Benefits

Besides demanding increasingly complex solutions, consumers also want accelerated delivery of new capabilities. It is a well-known fact that in today's highly competitive world, time-to-benefits is a critical factor in gaining an advantage. For most companies, gaining time-to-benefit advantage means decreasing the cycle time required for delivering a new capability. Historically, the two most dominant approaches were the project hand-off and concurrent development methods. While each of these approaches has merit in simple synchronous efforts, most organizations today are challenged when using these approaches due to their inherent limitations and constraints relative to complexity.

In the project hand-off approach, each functional team sequentially works on their element of the project, then hands both the work output and project ownership over to the next functional team in line. This approach is illustrated in Figure 2.3.

Figure 2.3 Project hand-off approach.

The limitations of such work are explained in the example entitled “The Perils of the Project Hand-off Approach,” the primary problem of which is that the work accomplished at each hand-off occurs within a single function. Errors introduced upstream can only be reconciled downstream, resulting in multiple rework cycles that consume time-to-benefit advantage.

The concurrent development approach originated to decrease cycle time over the project hand-off approach.8 It involves the various functional teams working simultaneously to deliver their elements of the capability under development (Figure 2.4). The concurrent development approach, however, has been found to be less than optimal in reducing development cycle time due to the big bang event that inevitably has to occur in concurrent development.

Figure 2.4 Concurrent development approach.

The big bang occurs when the concurrently developed work is integrated. Great inefficiencies can occur due to rework caused by poor requirements definition, lack of change management in the functional development efforts, and poor communication between the concurrent development teams. As a result, development teams may spend considerable time performing integration, testing, and rework due to these inefficiencies caused in an earlier cycle. Depending on the extent of any misalignment of the functional outputs being integrated, the concurrent method may actually lead to an increase in cycle time over a project hand-off approach.

Having now outlined two historic approaches and their limitations, a logical question is, “How do companies achieve a significant reduction in cycle time?” The best-in-class companies that we have observed, researched, or have worked for accomplish reduced cycle times through an integrated approach.

In the integrated approach, the cross-discipline teams work shoulder to shoulder during the work effort, from conception through end of life. To increase the probability of time-to-benefit efficiencies, the historically back-end functional activities such as manufacturing, validation, and testing are pulled forward in the work flow. Additionally, the front-end activities such as design and marketing are involved longer to ensure seamless integration. The big bang phenomenon is replaced by continuous, iterative-design, develop, and integrate cycles (Figure 2.5).

Figure 2.5 The integrated approach.

In order for the integrated approach to achieve its full potential, the cross-project, multi-discipline team is led by a program manager who can span the disciplines to ensure their work is indeed fully integrated for each cycle of work. Achieving time-to-benefit advantage requires tight management of the interfaces, shared risks, and open communication channels between the teams. This involves orchestrating, coordinating, and directing the work of the various specialty teams (see “Getting on the Fast Track”). The program manager brings the general management, business, and leadership skills required to effectively lead the integrated, cross-project team. By using an integrated approach, an organization has a higher probability for achieving time-to-benefit goals.

One company leader, Gary Rosen, Vice President of Engineering for Applied Materials Corporation, agreed with this assessment and described the role of program management in accelerating time-to-benefits:

If you have a strong program management function, products are closer to what the customers want and the team spends less time iterating late in the program to meet customer expectations. A program manager adds clarity for the engineering team by balancing market requests with engineering capabilities, therefore setting realistic customer targets. This results in more efficient use of resources which allows a program team to deliver what the customer wants the first time.

Delivering Business Results

Delivery of business results is the second aspect of business benefit realization attained by the implementation and use of program management. To reiterate, business results are the tangible business outcomes that result from the creation and delivery of new capabilities through the use of program management.

PMI identifies a benefit as an outcome of actions and behaviors that provides utility to an organization,9 while the OGC sees benefits as the tangible business improvements that support a firm's strategic objectives.10 Both organizations therefore recognize that programs and projects deliver benefits by enhancing current capabilities or developing new capabilities that support the sponsoring organization's strategic goals. A benefit is therefore a contribution to a strategic goal of a firm and in many cases cannot be fully realized until after the completion of the program. An important distinction being made here is that new or improved capabilities as the output of a program are the means to an end, and the anticipated business results define the end state.

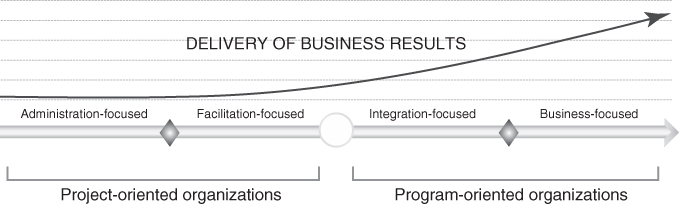

There is a direct correlation, however, between how program management is implemented within an organization and the amount of business benefit realized through the discipline.

We discussed in Chapter 1 that companies using program management apply it over a range of implementations based upon their company culture and program management philosophy and maturity.

Figure 2.6 illustrates that for organizations that are more project-oriented, the potential for business results being driven from the program management discipline normally is relatively low. Rather, the business results are often the responsibility of the business unit manager or of a department manager.

Figure 2.6 Delivering increased business results.

As a business makes a conscious decision to become more program-oriented, the responsibility for delivering business results begins to fall upon the program manager.

This has much to do with the different types of programs found within project- and program-oriented organizations and the difference in how they are created.

Generally, project-oriented organizations utilize formulated programs that are formed from the combination of preexisting projects and other work activities into a single entity. In this program type, a realization that the projects may be more effectively managed under a single program occurs. This realization is many times driven by a desire on the part of a firm's executive team to take a more strategic approach to the work that gets accomplished within their organization.

Critical to the formulated program type is the establishment of a common purpose or goal that ties the various project and work activities together. If this does not exist, it should be recognized that the organization most likely has a portfolio of projects rather than a true program composed of interdependent projects and the projects therefore should continue to be managed independently or consolidated in some other way.

Formulated programs require a clear vision be established early on to precipitate the identification of which projects should fall within the program, thus defining the scope of the program. Along with a clear program vision, direct linkage of the program to the appropriate strategic goals of the business is required. This enables the program team to map their project outcomes and deliverables to the desired business results.

In the case of formulated programs, it is common that investment in the various individual projects is made before the decision to invest in the program as a whole. This causes investment reconciliation to occur once the program is formulated since these types of programs are not originally spawned from strategic business goals of an enterprise.

In program-oriented organizations, by contrast, programs are most often driven from the strategic goals of an organization. Strategic programs are defined by strategic objectives, and therefore it is more straightforward to define the business results desired from the creation and delivery of the program output. The qualifier to this statement is that the level of ease is dependent upon how well the firm's senior managers define their strategic goals.

In most cases, an investment is made in a strategic program before the projects are fully scoped and planned. Based on this distinction, strategic programs are not defined from the bottom up by the scope of their constituent projects, as some definitions of a program suggest. Rather, they are defined by a top-down view of the whole solution that will enable achievement of the strategic goals.

Benefits Delivery and the Program Manager

Program-oriented organizations view the program manager as the business unit manager's proxy for managing the return on investment by delivering the business results anticipated. Some even go so far as viewing the program manager as the CEO (Chief Executive Officer) of a specific program. Few would argue that one of the main responsibilities of any CEO is the realization of improved business results.

To be effective, the program manager will need to keep the focus of a program on the business results, not solely on the delivery of a new or improved capability. This is an important distinction. Often a program manager gets so focused on the creation and delivery of a new product, service, or change transformation capability that they lose sight of the fact that these are the means to the end as discussed previously. This is not to say that the creation and delivery of a capability is not important. In fact, it is critically important. Without the capability there is no means to achieving improved business results. Our point, however, is that the capability in itself is not the primary goal. The goal is the business result that the new capability enables.