Chapter 3

Aligning Programs with Business Strategy

Historically, the primary managerial functions and processes of a company have been defined and viewed as independent entities, each with its own purpose and set of activities. For example, executive management normally performs the strategic processes that set the course of action for the organization. Portfolio management and project selection are commonly thought of as senior and middle management responsibilities. Program planning and execution processes are performed by the program manager and program team, while project managers and team leaders are responsible for project planning and execution processes. Each of these functions and processes are executed separately by a different set of people within the organization. At best, the strategic element feeds the portfolio element, the portfolio element feeds the program management element, and the program management element feeds the projects and specialty team execution. In many cases, this results in projects that may not be tied directly to either the business strategy or the organization's portfolio due to the lack of process integration.

Companies have come to realize that the time, money, and human effort invested in refining and improving each of their independent functions and processes have not brought them closer to effectively and efficiently turning their ideas into positive business results. Increasingly, this fact is leading business leaders to the realization that their independent entities can no longer remain independent if they wish to repeatedly achieve their desired business benefits and business value. Rather, they must be transformed into a set of interdependent elements that form a coherent strategy and business benefit realization system.

By taking a systematic approach through an integrated development model, an organization can realize improved business alignment between execution output and business strategy. As we demonstrate in this chapter, the program management discipline plays a pivotal role in the alignment process.

The Integrated Management System

When one looks at an entire business from a systems perspective, a holistic view emerges. Within the enterprise system, key subsystems such as the corporate mission, strategic goals, organizational functions, organizational structure, critical processes, and programs and projects exist to effectively and efficiently convert the resource inputs into the desired strategic outputs, such as corporate growth, increased productivity, or effective organizational transformation. Like any system, the subsystems are highly interdependent upon one another. For example, the mission of the business enterprise influences the strategic business goals defined, and the strategic goals define the business functions needed and how they should be organized and interact.

Additionally, the business enterprise operates within, and is influenced by, a dynamic environment. Examples of environmental factors that have an impact on the mission, structure, operation, and output of the business enterprise system include shareholder expectations, domestic and world economic conditions, technology trends, customer usage models, and competitor actions.

The heart of the enterprise is a system of management functions and critical processes needed to convert inputs into outputs. We refer to this set of functions and critical processes as the integrated management system.1 Illustrated in Figure 3.1, this system is the mechanism from which new products, services, infrastructures, or organizational transformation initiatives are conceived and developed to realize the mission, strategic goals, and business benefits of the enterprise.2

Figure 3.1 The integrated management system.

It is important to view the integrated management system as a coherent end-to-end system from understanding market and environmental conditions, to the development of strategic goals that support a company mission, to the delivery of business value. This end-to-end structure allows for more flexibility and receptivity to changes in the dynamic business environment.

By contrast, taking a noncoherent approach is analogous to actions one may take if an automobile is performing poorly and exhibiting below-par performance symptoms, such as low fuel efficiency or rough idling. By taking an ad hoc approach to the problem, one may try to treat the low fuel efficiency by adding a fuel oxidization additive or replacing the fuel filter. To treat the poor idling problem, one may change the spark plugs or adjust the engine timing. Any or all of these actions may yield an improved performance for a period of time, but they will not solve the root problem if the automobile is in need of an overall tune-up. Only by viewing the engine and ignition functions of the automobile as a system does a holistic approach to diagnosing and resolving the root problems become possible.

With this analogy in mind, we view the integrated management system as being comprised of two primary components: 1) the business engine and 2) the execution engine (Figure 3.2). The business engine consists of the strategic management, portfolio management, and program management element of the business. The execution engine consists of the team execution, project management, and again the program management elements. Program management is the overlap between the business and execution engines of the business and serves as the organizational glue that aligns strategy and action, which is necessary to deliver business value.

Figure 3.2 Business and execution engines of an organization.

The Business Engine

The business engine of the integrated management system is composed of three primary functions: strategic management, portfolio management, and program management. Strategic management involves definition of the company mission, identification of strategic goals, and creation of strategies to achieve the goals. Portfolio management includes the review and selection of the strategic options (programs) to be implemented, evaluation of the success of the strategic process in achieving the organizational objectives, and alignment of the organization's funding and resources to the most strategically important programs. The program management element of the business engine involves translating strategic goals into solution possibilities and execution requirements, developing and validating a business case, and delivering the business benefits through creation of new capabilities.

Strategic Management

Strategic management is defined as a set of decisions and actions that result in the formation and implementation of plans designed to achieve a company's objectives.3 The mission statement is a broadly framed statement of intent that describes why the company exists in terms of its purpose, philosophy, and goals. Strategic goals define what the business wants to achieve over the strategic time horizon, which is typically three to five years. Strategy is the business' game plan that reflects how it will accomplish the strategic goals and mission. It is imperative that all three elements of strategic management be in place to properly set the direction of the organization. Figure 3.3 shows a generic strategic management process flow.

Figure 3.3 The strategic management process flow.

Mission

Some have argued that a company's mission is of little use because big, lofty visions are rarely realized.4 However, without a mission, a company lacks the overriding statement of purpose for the business (its philosophy toward its customers, employees, and competitors), and its goals such as growth, profitability, or service to the community. Most importantly, without a mission, it becomes difficult to judge the relevance of opportunities, threats, and program options presented to a company's management team.

In our view, defining the company's mission is perhaps one of the most important responsibilities of the senior management team. The mission statement defines why the business exists, what the strategic intent of the company is, what its core values are, and how the management team measures success. It should describe the company's products or services, markets or customers, and specialty areas of emphasis in a way that demonstrates the values, priorities, and goals of the management team.5

Financial and economic goals may influence the mission and strategic direction of the enterprise and may be either explicitly or implicitly stated in the company mission statement. Take, for example, the following mission statement from Proctor & Gamble, which explicitly includes sales and profits as part of its mission statement:

We will provide branded products and services of superior quality and value that improve the lives of the world's consumers. As a result, consumers will reward us with leadership sales, profit, and value creation, allowing our people, our shareholders, and the communities in which we live and work to prosper.6

A mission statement for nonprofit organizations is equally important, as they describe why the organization exists, defines the services they perform, and what is driving the passion for human good by the people providing the services. The mission statement for Bella Energy is a good example.

The Bella Energy mission is to provide the highest quality solar energy solutions to empower communities with opportunities to contribute to a sustainable future and clean energy economy.7

A good mission statement promotes a sense of shared expectations among all members of the organization, provides common purpose, and direction for the company, and defines a company's intent for shareholders, donors, employees, customers, suppliers, and the community in which it operates.

Strategic Goals

As stated earlier, the strategic goals define what the company wants to achieve within a multiyear period. To achieve long-term prosperity, management teams commonly establish strategic goals in the following seven areas:8

- Profitability

- Competitive Position

- Employee Relations

- Technological Leadership

- Productivity

- Employee Development

- Public Responsibility

In order to accomplish its mission, an enterprise will develop a set of short-, medium-, and long-term goals to focus the effort and outcomes of its workforce. These strategic goals are normally found at two levels: corporate strategic goals and business unit strategic goals.

The purpose of corporate-level strategic goals is to align the various business units toward a common purpose and direction, while business unit strategic goals serve to focus the functional departments and outcomes of the people within a business unit.9 Every enterprise is unique, and therefore every enterprise will have its own set of strategic goals. It is common, however, to find strategic goals centered in a number of areas, including:10

Financial: The ability of an enterprise to achieve its other strategic goals depends greatly on its ability to achieve its financial goals. These goals aim to increase return on assets invested and may include increasing return on investment, increasing profitability or operating budgets, increasing revenue or funding received, or lowering the cost of doing business.

Productivity: Productivity goals normally focus on how efficient an organization is in creating output from input, and may focus on decreasing cost of goods produced, reducing cycle time in creating solutions, or increasing reuse.

Competitive positioning: This refers to a business's relative rank in the marketplace as compared to others that it competes against. This is usually measured in total sales, total revenue, or percentage of total market share.

Customer or user adoption: Adoption refers to the number of customers or users who regularly use a company's offering. These goals center upon increasing the number of people who buy or use an offering.

Improving human condition: Human condition goals are normally focused on creating a positive change in the lives of a select population. Some examples include decreasing incidents of diseases, increasing the use of social services, and changing human rights policies within a region.

It should be pointed out that a business normally does not strive to identify strategic goals in all areas presented above, but rather only in those areas that align with and fully support attainment of the corporate mission. Additionally, a strategic goal should be specific in nature by stating what will be achieved, when it will be achieved, and how it will be measured. A goal must be challenging enough to raise the bar on corporate performance, but attainable to prevent employee frustration and lack of motivation.

Strategies

Strategy defines how a business will achieve the strategic goals it has established and consists of the portfolio of ideas that, when fully developed, will contribute to the attainment of those strategic goals.11 In a program-oriented company, programs constitute the primary strategies that produce superior products, services, infrastructure solutions, and transformative change. The sum of the outputs of the programs within a portfolio will provide the combined means to achieve the desired strategic business goals.

Portfolio Management

A firm's portfolio management process constitutes the second element of the business engine of an enterprise. Portfolio management is defined as “a dynamic decision process, whereby a business' list of active [programs] is constantly updated and revised.”12 As is usually the case, organizations have many more product, service, infrastructure solution, or organizational change ideas than available resources to execute them. As a result, resources can become overcommitted, and the organization must find a way to broker competing demands for its limited resources. Portfolio management is an effective process for identifying and prioritizing programs that best support attainment of the strategic goals. Programs are ranked and prioritized based upon a set of criteria that represents business value to the organization. Senior management can then allocate available resources to the highest value and most strategically significant programs.

According to the model developed by Robert Cooper, Scott Edgett, and Elko Kleinschmidt, the three fundamental principles of portfolio management are: 1) establishing a strong link between the portfolio and organizational strategy, 2) achieving a balance of programs based upon investment priority, and 3) maximizing the value of the portfolio of programs in terms of company goals. We would add that accomplishing these principles should result in matching the number of selected programs with the available resources. This is sometimes referred to as resource capacity planning.

Establishing a Strong Link to Strategy

Through the alignment of an organization's investment funding and resources to the work that is the most strategically important, portfolio management maximizes strategic return on investment. As Cooper and his colleagues so eloquently explain, “Well-meaning words on a strategy document or mission statement are meaningless without the funding and resource commitments to back them up.”13

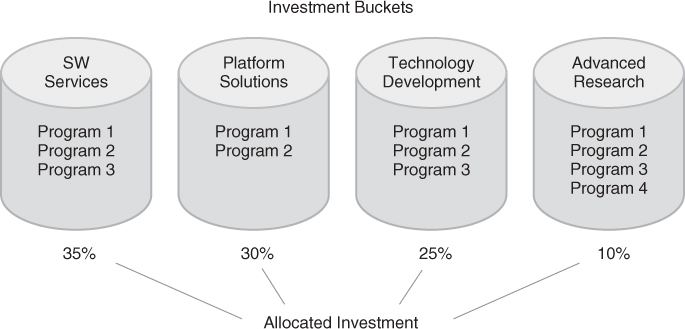

Ensuring strategic intent can be accomplished through a couple of means. First, the portfolio structure should support the strategic goals established, and second, strategic elements must be included in the portfolio prioritization criteria. Strategically structuring a portfolio can be accomplished by using an investment bucket approach. The selection and structure of the investment buckets are unique to each business, and are highly influenced by a company's strategic goals, market segmentation, and product, service, or infrastructure types.

For example, a financial industry software company we worked with defines its portfolio structure on the basis of funding its strategic goals. The strategy statement is as follows: Drive material impact on (our) margin, growth, and industry influence by bringing to market software solutions and services, and delivering new technologies that enhance the value of (our) solution platforms.

The portfolio investment buckets for this organization are shown in Figure 3.4. Notice the direct correlation between the strategic intent of the organization and the structure of its portfolio of programs. Also shown in this illustration is the fact that each portfolio bucket consists of a set of programs that become the means to deliver the strategic goals.

Figure 3.4 Aligning portfolio structure with strategic intent.

Achieving a Balanced Portfolio

Creating a balanced portfolio involves making thoughtful decisions at the macro level on what types of programs the company chooses to invest in, and what level of investment will be provided for each type. This is analogous to the decisions one makes concerning personal financial portfolios. One decides which types of investment vehicles to invest in (stocks, bond, mutual funds, cash, etc.), and what percentage is allocated to each type based on risk tolerance and short-, medium-, and long-term goals.

For the software company discussed previously, a decision had to be made about the priority of funding and resources to be applied to each of the investment buckets within the portfolio. As shown in Figure 3.4, 35 percent was allocated to software services programs, 30 percent was allocated to platform solution programs, 25 percent was allocated to technology development, and 10 percent was allocated to research.

Balancing the portfolio achieves two critical elements for a business. First, it allocates funding based upon strategic intent and priority. Second, it dedicates funding and resources to specific programs that constitute the portfolio.

Maximizing the Value of the Portfolio

The foundation for an effective portfolio management process is the ability of the management team to determine the factors that constitute program value for their organization. The team must establish a prioritization system to evaluate one program against the others within a portfolio. Once it gets beyond this hurdle the organization will have accomplished the following two things: 1) a real understanding of how value is defined, and 2) a prioritized portfolio of programs that clearly differentiates between those that provide the most and the least value to the business. Once these two are accomplished, maximization of the portfolio has been achieved.

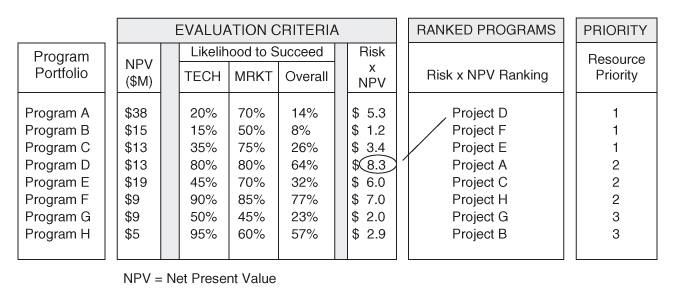

Figure 3.5 is an example of a prioritized portfolio of programs from a manufacturer of Internet communication products. Prioritization of the portfolio is accomplished through the use of two evaluation criteria: 1) net present value of each program, and 2) the combination of technology and market adoption risk. Each program within the portfolio was first ranked based on net present value. The net present value of each program was then multiplied by the overall risk (technology risk × market risk = overall risk) associated with each program. The programs were again ranked based upon the risk multiplied by NPV. Notice how the prioritization changed with the use of a second criterion.

Figure 3.5 A portfolio of programs ranked by value and risk.

Once the ranking was known, allocation of resources then occurred in priority order, with priority one programs receiving full allocation of resources, priority two programs receiving full allocation of resources once priority one programs were fully staffed, and priority three programs receiving full resources once priorities one and two programs were fully staffed.

With programs ranked and resource prioritization complete, the management team of the organization was able to allocate its resources to the programs that provide the most business value to the organization, therefore achieving maximum output from a limited input.

Executing good decisions that give the portfolio a robust set of programs that reinforce the strategic goals of the business requires strong leadership from executive management. Executives must ensure that the process is effective and that the tough choices are objectively made through quantitative and qualitative analysis, dialogue, and debate. Without strong leadership, an organization will continue to overcommit its resources and underachieve attainment of its strategic goals. The example entitled “Do You Agree with This Portfolio Verdict?” demonstrates one such scenario.

Program Management as Part of the Business Engine

The role of program management in a firm's business engine is to be the delivery mechanism of the strategic goals established during the strategic management process and for achieving the business benefits identified during the portfolio management process.

An organization's program managers do not create the mission or strategic goals; this is the role of senior management. The program managers do not plan and execute the project deliverables; this is the role of the project teams. The program managers do ensure the attainment of the value proposition of a program by delivering an integrated solution through the collaboration and coordination of multiple interdependent projects and business functions. This ensures alignment between business strategy and project execution is established.

But what is alignment? Alignment refers to the degree to which a program mirrors and supports the priorities of the organization's business strategy. Additionally, it is the degree to which the business strategy is used to guide objectives and work outcomes of the execution team. The program vision is the keystone element that provides this alignment. It establishes the end state that defines success for the program and provides guidelines for what to do and how to do it. The program vision is composed of three critical elements: 1) the program objectives, 2) the whole solution, and 3) the program business case.

Program Objectives

Remember, each program delivers a portion of the overall strategic goals for a firm. It is rare that the successful execution of a single program results in the attainment of all strategic goals. Rather, it takes the successful execution of a number of programs within the portfolio.

Each program then carries a set of program objectives that are designed to achieve specific strategic goals. As Figure 3.6 illustrates, the program objectives result from a combination of the various strategic goals of the organization.

Figure 3.6 From strategic goals to program objectives.

The program objectives provide the translation from strategic business goals to actionable execution objectives specific to a program. For example, a strategic business goal to achieve increased market growth could be translated into a program objective to reach a specific number of orders in the first year following capability introduction. Similarly, a strategic business goal to provide lowest-price offerings could be translated into a well-defined cost objective for a program.

The Whole Solution

When we are working with program teams to establish a strong program vision, we use the term whole solution to describe the product, service, infrastructure solution, or transition that the program team will create and introduce into the market or organization. As we explain in more detail in Chapter 4, the whole solution includes the conceptual architecture of the solution and all other components that have to be created or enabled to completely meet the expectation of the customers and users.

This tends to be one of the most difficult tasks in creating the program vision, as it requires a team to visually represent the whole solution that they and their partners will provide. The level of difficulty is matched only by its level of importance as it is the whole solution that defines the program architecture and structure of the program team and demonstrates the level of cross-project integration that needs to occur to achieve the business goals driving the program. When completed effectively, the whole solution shows that success cannot be fulfilled by any one specialist or set of specialists on the team. Rather, success comes when meeting customer expectations is a shared responsibility between the members of the project teams, with their work tightly interwoven and driven toward the integrated solution.14

The Program Business Case

The purpose of the program business case is to demonstrate that a program supports the strategic goals of the organization and is used to determine if the organization should invest the financial, human, and capital resources to fully execute the program (Chapter 6). Portions of the program business case are vital in establishing the program vision by describing the business opportunity available and how the program will achieve the opportunity and business strategy.

To do this, the program business case spells out the business benefits of the program and the rationale as to why the program outcome is desired by the customers, users, or the organization, and why it is better than other alternatives. It is core to the establishment and execution of the program vision because it is the means to securing the funding and resources necessary to execute the program and for continually evaluating the progress of the program toward achieving the strategic business goals intended.

In program-oriented organizations, development of the program business case is led by a program manager and provides the direct link between the program and the firm's portfolio process. In these organizations, the approval of a program business case is the means for a program to enter the portfolio. As explained earlier, the program is then evaluated against other programs vying for organizational funding and resources. Clearly, the stronger the business case, the higher the probability a program will receive the investment needed.

The Execution Engine

The execution engine of a company is responsible for turning ideas into reality, turning architectures into solutions, and turning strategy into action. It is widely recognized that strong and healthy companies have strong execution engines, as this is where the means for generating growth and positive change resides. The execution engine of the integrated management system comprises three primary functions: 1) team execution, 2) project management, and 3) program management.

Team Execution

At the foundation of the execution engine are the teams of functional specialists whose knowledge, skills, and expertise are honed for creating new capabilities for the enterprise, its customers, and its stakeholders. Specialization of labor has long been recognized as the keystone to advancements gained during the industrial and modern ages.15 Because programs tend to be complex in nature, the solutions that are created from the work performed on the program need to be systematically organized into functional specialties. This is core to a systems approach.

It is common for execution specialists to report to and be part of functional departments within a company that serves the purpose of maximizing the competency of the specialty. The functional departments then assign their specialists to the programs as needed. Within program-oriented organizations, the functional specialists become part of the functional- or discipline-specific project teams where the charter of the project is to create and deliver the subsystems that make up the whole solution. Their work therefore is guided by the objectives of the program as a whole, but through the execution of the projects within the program.

When the integrated management system is operating effectively, each member of an execution team should understand how their work contributes to both the creation of the integrated solution and achievement of the business goals desired. If done correctly, a software engineer, for example, will be thinking about business value as well as about the performance of the code he or she is creating.

Project Management

The strength of a company's execution engine is its ability to become highly efficient. This is accomplished through repeatability and predictability of every process, every task, and every activity—this is the charter of the project management function within program-oriented organizations.

The Project Management Institute's PMBOK® provides a masterful guide of effective methods for driving projects to success in the modern world. The project management knowledge areas and processes contained in the PMBOK® are designed to complete work in the most efficient, repeatable, and predictable means possible. The application of these practices is as relevant on a program as they are on an independent project. However, management of a project within a program involves some significant differences.

The first, and debatably the most important, is a difference in mindset. The overall focus for a project team must shift from one of my project, to a mindset of our program. Thus, a duality is introduced on projects within a program where a project manager must maintain command and control of a project, while collaborating with all other actors on a program to achieve program-level success. This is due to the highly interdependent nature of the projects on a program.

Since projects are evaluated on program-specific success factors, project managers must define, scope, and plan their projects in relationship to the overall program. Project scope is not defined entirely by a project's outcomes and deliverables, but rather also by its contribution to the program objectives and business benefits intended. This requires that the project managers within a program directly link their project deliverables to the stated program objectives. One must be able to trace deliverables to project success criteria, to program objectives, and to business benefits.

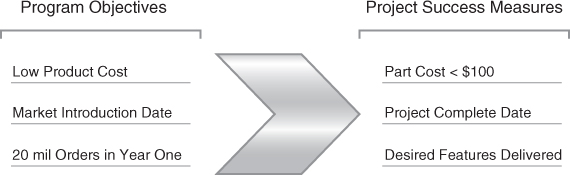

Just as a program delivers a portion of the overall strategic goals for a firm, each project on a program delivers a portion of the program objectives. As the example in Figure 3.7 illustrates, the project performance measures are driven by the various program objectives.

Figure 3.7 From program objectives to project success measures.

For example, a program objective of low product cost could be translated into project success criteria such as part cost < $100 as well as total budget at completion for a number of the projects on a program. Likewise, a market introduction date program objective will likely translate into project completion date success criteria for each of the projects.

The alignment of project success criteria to program objectives requires project managers within program-oriented organizations to evolve from being strictly command-and-control execution managers to also performing certain aspects of the role of a first-level business manager. This is necessary to help ensure that the project outcomes from the execution engine of a firm are driving toward business benefit achievement.

Project managers on a program have to define their projects in terms of business benefits and as a single component of the whole solution. Project managers therefore have to be able to think systematically and holistically about their outcomes and deliverables, and be able to tailor their project performance indicators toward achievement of program objectives, not toward project performance entirely.

This evolution requires some change to the traditional project manager role. Seasoned project managers have years of experience being held accountable for the success of their own independent projects. As a result they have honed their philosophies, knowledge, and skills toward becoming masters at managing to baselines, completion of project-focused tasks, deliverables, and milestones. Moving from a philosophy of individual accountability in managing an independent project to a team accountability philosophy necessary on a program can be a challenging transition for some organizations and will take some time and diligence.

Program Management as Part of the Execution Engine

It is important to remember that there are two parts to successfully achieving one's strategic goals: setting the strategy and executing the strategy. Many times organizations fail to put adequate emphasis on the execution of strategy, and what they end up with is nothing more than an unfulfilled strategy statement.

The role of program management in a firm's execution engine is to provide translation of business activities to execution activities, perform the integration and synchronization of outcomes from multiple projects, and help the project execution teams effectively and efficiently navigate market and organizational change.

Business to Execution Translation

When gaps occur between a firm's execution activities and business activities, many times it is due to ineffective translation between the two types of activities. Program management provides this critical role. For example, program management translates strategic business goals to program objectives as described previously. As part of execution, the translation must continue by translating program objectives to key project performance and success measures. This ensures that the direction, command, and control of each project is aligned to and supports the strategic goals driving the program as a whole by creating traceability from strategic goals, to program objectives, to project performance.

Additionally, the program management function provides the translation of the whole solution to the program architecture that defines the projects and other components that are needed to create and deliver the whole solution. Additional translation is needed for the execution teams to convert program components to project outcomes or deliverables. This is normally accomplished through the development of a program-level work breakdown structure (Chapters 6 and 9).

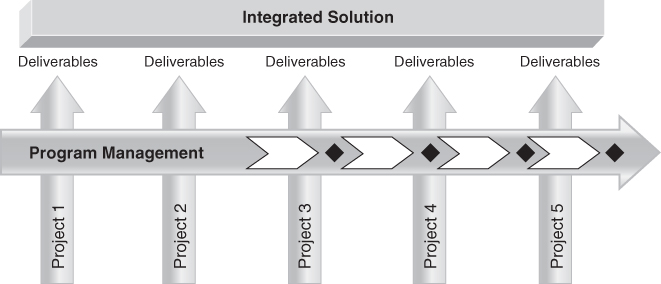

Cross-Project Integration and Synchronization

The second critical role that program management fulfills for the execution engine is that of integrating the outcomes of each of the projects within the program to create and deliver an integrated solution. Figure 3.8 illustrates how program management provides the systems-level synchronization, management, and integration needed to tie the components of a solution together to create a holistic outcome. In doing so, program managers works horizontally to drive collaboration across the project specialties.

Figure 3.8 Cross-project synchronization and integration.

Integration of project outcomes and deliverables is impossible if the work within the projects is not occurring at a synchronous cadence at the program level. In this regard, a program manager is much like an orchestra conductor. Even though each of the instrument sections of an orchestra has their own music to produce, the conductor ensures each of the sections steps through the musical composition at a consistent tempo and in concert with each of the other sections. This ensures that an integrated, blended, and harmonious musical piece is produced.

Much is the same on a program. Since the responsibility for managing the interdependencies between projects on a program falls upon the program manager, he or she must work to ensure that the workflow within each project is occurring at an integrated and harmonious pace. Synchronization, therefore, involves ensuring that project timelines are aligned, that cross-project deliverables are planned appropriately, and that the work within each project is occurring at the appropriate pace.

Navigating Change

Execution teams by nature and by design resist change. Project success is determined by evaluation of the amount of variation from a preset baseline. Change inherently introduces variation from the baseline, and therefore introduces risk to execution success.

Programs, however, are ambiguous and uncertain by nature, which brings with it a high probability of change. Often, a program can be as much about learning as it is about producing an outcome. Therefore, change must be expected and embraced. This of course creates a problem for the execution engine of an organization.

The program manager has a complicated duality to contend with in regard to change. He or she must protect the project execution teams from unnecessary change that will disrupt their performance, while at the same time be the advocate for change on a program when the change brings improvement to the business benefits or protects the program from risk.

Change at the program level is a navigation process, not a control process. Since a program is ambiguous and uncertain, project execution—and the program in its entirety—cannot be planned and executed to a strict baseline and set of targets. This is a hard lesson learned that we have witnessed many organizations struggle to comprehend, especially those early in the process of transitioning from a predominately project-oriented organization to being more program-oriented.

To be successful in a changing environment, the program as a whole and the execution team specifically must be given a set of thresholds that act as guard rails around their baselines. Additionally, buffers must be established for time and cost—like upper and lower control limits or parameters of acceptable performance. This will allow the program team latitude to navigate change successfully instead of attempting to control change which is nearly impossible.

Aligning Execution with Strategy

For program-oriented companies, it is not by coincidence that program management is at the heart of both the business and execution engines of the enterprise—it is by design. This is not to say, however, that program management is the most critical of a company's management systems. All are important and each has its function to serve. For program management that function largely is to create and maintain alignment between execution work outcomes and what the company is trying to achieve strategically.

As we stated earlier, many companies perform exceptionally well without adopting program management. Many times the existence of an effective portfolio management process is sufficient to align a set of independent projects to the strategic goals of an organization. However, the need for transition to something different is triggered when the organization begins to experience a rise in complexity. This may include complexity of the solutions under development, complexity associated with the number of business functions required to be involved in creating solutions, complexity associated with the geographical distribution of work, and complexity associated with strategic alliance and co-development partnership arrangements.

The result of this rise in complexity is often realized in a misalignment between project deliverables and the business strategies within the organization. This misalignment eventually causes disruption in business results. In working with a number of firms, we have witnessed a threshold of complexity that, once reached, triggers the beginning of the disruption. For project-oriented organizations, disruption may occur because of a non-incremental increase in the number of projects required to manage the complexity, and the need to manage a large number of cross-project interdependencies.

For a number of years, some authors were advocating the need for strategic project management, where they stressed the importance for project managers to develop strategic business skills in order to fill the gap that was arising. While good in theory, in practice this makes little sense. As stated earlier, strategy has two sides, development of strategy and execution of strategy. Project management is best when hyper-focused on effective and efficient execution of the strategy. Becoming more “strategic” does little more than serve to dilute the value of project management for an organization.

Rather, we have found that senior leaders of organizations begin to look for a more systematic and integrative approach to solve the disruption problem caused by increased complexity, and begin to explore the principles of program management as a solution. Here is what one such leader, David Churchill, a former Vice-President for Agilent Technologies, said about the role of program management:

Most firms have the right product ideas, technical talent and marketing capability to support their business strategies. Organizations many times have difficulty performing to expectations when they cannot turn their strategies into successful execution. Program management is strategic to the firm because it provides the ability to convert business plans into actions that will achieve the intended objectives; it helps bridge the gap between strategy and execution.

With this, however, is the challenge to establish program management correctly within an organization, and to focus on the critical aspects of program management that creates the strategy-execution alignment. The critical aspects that are presented in this chapter are a strong program vision and documented traceability between strategy, program, and project success measures. Table 3.1 illustrates a number of examples that demonstrate the alignment between strategic goals, program objectives, and project success measures.

Table 3.1 Strategy, program, and project alignment examples

| Strategic Goals | Program Objectives | Project Measures |

| Be first to market with a new web-based service |

|

|

| Provide the lowest priced product on the market |

|

|

| Increase throughput by decreasing time of customer transaction and quality of service |

|

|

| Meet demand for a 25% increase in services by 2017 |

|

|

It is critical to remember that alignment is not static and should not be treated as a one-time activity. Aligning strategic goals, program objectives, and project performance measures are normally performed early in the program cycle, at a time when much is still unknown and many assumptions are made about the environment in which the program is operating. The likelihood of change is therefore high and should be planned for accordingly.

The program manager has the responsibility for periodically validating and, if necessary, adjusting the alignment parameters to match market or business changes. Occasionally, this may lead to a discussion with the senior leaders of an organization about the validity of the strategic goals driving a program. This process provides strategic feedback and helps to keep a company strategically aligned to changes in their environment.16 An example of what can happen when the strategic feedback sensors are not in place is provided in the story entitled “Asleep at the Wheel.”