5

OPERATING MODEL: Making It Work in Practice

Documenting the Future Model

Throughout this book we talk about the elements that allow companies to profit from Procurement. And we believe there is significant scope for this—whether that is through setting the right ambition, getting the right team in place, understanding how to execute high quality Strategic Sourcing, measuring savings, making the right technology decisions, and more. Yet there is one element that is fundamental to all these others. It is the foundation upon which all the others depend. Without this element, you wouldn't be able to achieve your ambition, and you wouldn't get much value from your technology. Your team could not reach its potential, and you certainly would struggle to execute Strategic Sourcing well to continue to bring ever more value to your company.

That element is an operating model, and it is the thing that brings and then holds everything together. If you work in a Procurement function, especially a larger one, then it's quite possible you will have documented your operating model. If so, it was probably the result of a deliberate workstream to improve it from a previous state. Your operating model will describe how your people work and what they should do. It describes how they are organized. And it describes how these people interact with technology, data, and processes.

So far, so standard. This is surely not news to anyone. But this is precisely the problem some organizations have with their documented Procurement operating model. It describes how they should work but not how they actually work.

Before we discuss what is perhaps the hardest part of the operating model, which is how to make the transition from the current to the desired ways of working, we should first talk briefly about the steps behind defining a to-be model. We expect most readers will be familiar with this, but it's worth recapping.

Having a vision is the first step. As we discussed in the second chapter on “Ambition,” this needs to be aligned to the strategy of the business. What are the goals, objectives, and risks of the business and how does the supply chain, and Procurement specifically, contribute to those—positively or negatively? With this as the context, what is the mission of Procurement?

Cost optimization will likely be a key part, as we have discussed elsewhere in the book, but not necessarily the only part. This mission is then ready to be translated into your vision statement for the Procurement function.

Good vision statements are clear and easy to understand for the uninitiated. Free from jargon, they succinctly articulate Procurement's desired and realistic contribution to the business, which aligns perfectly with the business's overall strategy. This last point is crucial because it means there should be no conflict with other functions when setting out to achieve the vision.

Next, CPOs focus on how this vision breaks down across the elements of the Procurement function. There are many models out there that describe the different elements of the Procurement function, but they can almost always be summarized as people, data and processes, and technology. An example of a framework for this that we have seen many companies use in the past is as follows: Strategy and Organization; Demand and Stakeholder Management; Sourcing Process; Settlement Process; Supplier Management; Policies, Controls, and Compliance; Technology and Data; and People Skills and Incentives (see Figure 5.1).

Figure 5.1 Elements of a Procurement Function

For a more in-depth look at how this type of exercise can be used as part of planning the roadmap for your transformation, see Chapter 13: Roadmap.

At this point CPOs will, correctly, ask themselves the following sorts of questions: What is the current status of my function against each of these dimensions, and what are the one-, two- and three-year goals for each based on my vision statement? What objectives does that create for my function in the short-, medium- and long-term? Based on where I am today, what are the gaps and change requirements? How can these be organized into workstreams and sub-initiatives that form an overall plan?

By answering these questions, gaps are identified between the as-is and to-be, and recommendations are deduced. For example, perhaps the team needs to mirror the structure of the business to better serve it, or the team needs some additional skills that can be obtained through training or other learning opportunities. Sometimes a new Procurement policy is necessary with some technology enablement. Finally, the new operating model is sketched out which includes organigrams, roles and responsibility maps (RACI diagrams), skills profiles, and new processes.

It's important to note that, while understanding what the best in the industry are doing in these dimensions is useful as you work to sketch out this to-be model, you need to understand the dimensions on which you want to focus. Understand what Procurement is going to excel at in this business, based on the business priorities and relative strength and weaknesses of other functions, and pick two to three elements at most. Perhaps it's data and technology. Or perhaps it's market expertise. That does not mean you are not going to be good at other elements but functions that try to excel at everything sometimes struggle to excel at anything.

Once you've got this to-be picture and a plan to get there from your current state, it's important to socialize it and test it with other key departments to see how their vision, plan, and objectives align or conflict with yours, tweaking if necessary. The most important thing about a to-be model is that it supports the overall corporate strategy and that of peer functions.

The Center-Led Approach

The foundational layer

One of the key questions you will need to answer when designing and documenting your model is how much to centralize your Procurement function. This is the foundational layer. While a purely centralized function is suitable for some organizations, and many organizations have decentralized functions following years of acquisition and lack of integration across companies, a more balanced center-led function has become the most common practice in recent years for companies wanting to get ahead. And this is true not only of the Procurement function. Center-led functions for HR, IT, and other functions that have traditionally played a supporting role in business, have become common.

In the center-led model, each of the dimensions of the framework we have just touched on are centralized (which means ways of working defined by the center), but there is an element of freedom at a local level, be it geographic or business unit, to apply those standards and practices. For example, in the center-led function the sourcing and supplier management processes become standardized but may contain additional steps that can be applied locally.

The benefits of the center-led model are numerous. Firstly, it allows a company to properly leverage its spend. By centralizing demand, it is able to leverage spend and take advantage of economies of scale. It also enables the leveraging of talent across the business. With a central oversight of people in the organization sitting both centrally and locally, ensuring the right skills exist in the right places and sharing knowledge between otherwise disparate resources is much easier.

Centralized processes ensure consistency of approach and a familiar customer experience each time someone from the business interacts with Procurement. This is especially important in elevating the Procurement function and building credibility with stakeholders. And with centralized systems, there is a common language and one version of the truth—particularly in relation to spend, contract, and supplier performance data. Without this one version of the truth and solid master data that underpins it, your ability to be a reliable provider of insight that can drive decision making is severely limited, as we discuss in more detail in Chapter 10: Technology.

But by allowing a level of freedom to local geographies and business units to interpret and apply some of these standards to suit their needs, you retain some agility which is required to keep those geographies and business units operating effectively. Too much dictating from the center can be inappropriate.

Which leads us on to how you go about grounding the above theory in reality to make the model work. This is where the art really lies, in knowing how much to centralize to drive economies of scale and optimize ways of working while maintaining flexibility to accommodate local requirements and nuances. There are a number of things to consider.

Firstly, you should look at how the other functions are set up. Remember we spoke about HR and IT earlier in the chapter? Well, are they center-led? Perhaps they are completely decentralized. Knowing how they are set up is important because there might be a reason why that is so, and it's quite possible that could be what works best in the company. Understanding the reasons behind their current setup will be useful to you in deciding what to do with your Procurement function.

Secondly, are you master of your Procurement universe? Many CPOs are not. Maybe IT has its own Procurement and vendor management team. Perhaps there are global process owners for some of your Procurement processes who don't even sit in Procurement. Or maybe Marketing has refused to engage with Procurement for the last few years. Depending on the answers to some of these questions, you will need to pick your battles when deciding how much to control and then centralize each element. It's also important to note at this point the readiness of your company to move to the model you want. Maybe you can identify the end state, but if the company is not ready for that end state then considering a phased approach is best.

And finally, what are the structures of the supply markets and commonality of business needs? Where regional or global supply bases are mature and can serve approximately 80% of business requirements, then the opportunity exists to leverage the full category spend in a more efficient manner by directing category strategies and supplier selection centrally. Similarly, if business needs are common, or can be harmonized, this provides the opportunity to drive efficiency and create a larger common volume to be leveraged.

So, given this, what are the implications for the organization design? Effective global Procurement always needs an element of central leadership as we have discussed so far to shape the direction and drive the program. Two models are common. A “thin” model with a small central leadership function directing and coordinating policy, strategy, and direction—but with the actual sourcing activity led by local teams on a delegated basis, with lead-buyers appointed in the regions—is usually the one with the largest spend concentration.

This is a commonly adopted model for confederated global businesses, but getting it right is not easy, as a common risk is the delegated regional category lead not having the effective remit or incentive to deliver value for business outside their own region. It is therefore common in this model to change reporting lines for these staff into the central CPO to help coordinate and drive action.

The second is a “thick” model, more common in companies with higher correlations of global oligopoly supply markets and very similar business needs. In this model, certain spend categories are designated as global, and the full category management accountability sits with a central team, managing specific categories on behalf of regional business units. This model is common in global Manufacturing and fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG) companies, and can drive significant efficiency as well as provide stronger coordination in supply base investment, innovation, and product development.

The category layer

Once you have decided on the extent to which to centralize your function, it is important to decide how you are going to set up your major spend categories. And just because you have a centralized function, it doesn't mean that central Procurement is going to manage all of your spend categories. For some categories that might be appropriate; but for others you might, for example, have a central strategy but allow the local geographies and business units to apply it locally. Or you might have categories that will be set up in a more decentralized manner and are managed by the business.

One of the most effective approaches we have seen to getting to the right model for each category is to set up a category council that consists of all the key people (for example, budget holders, Engineering, Procurement, end users, and divisional managers, or their equivalents) deciding on the overall strategy, supplier roster, and supplier management program, including defined roles and responsibilities in a fully integrated and aligned way.

For an indirect category it is likely that Procurement will be in the lead with input from the rest, but for other categories Procurement has a more supporting role and embeds itself in the relevant operations function with a dotted reporting line from the function to Procurement. This way, the Procurement model provides the advantages of centralization and standardization, while safeguarding the specific requirement of category characteristics by applying a flexible, integrated and custom-built way of working with business partners.

Another organizational aspect to consider, when setting up categories of spend, is how to staff them. For many years, there was a trend to put in place a category manager model, where it was the category manager's responsibility to address the category spend only—which often meant working across many different stakeholders who shared that category spend.

More recently, organizations have deployed a business partnering model where the Procurement organization mirrors the business functions, essentially allowing Procurement to better man-mark its internal customers. This latter model involves having a roving pool of sourcing managers beneath these business partners that harness the synergies from the different business areas. We talk more about our recommendations in this area in Chapter 4: People.

Ultimately though, these are all just org charts. What's more important is how it actually works.

Shifting from Reactive to Proactive

Building your to-be model and working out how to organize yourself globally is all well and good. But at this point it is vital not to fall into the trap of expecting a Procurement organization to make a huge leap from as-is to to-be almost overnight, because this won't happen. Not only is it far too much change at once, but it assumes people can start working on very different activities almost immediately, with a different focus, without finding a solution for all the stuff they are busy with today, however non-value adding that stuff may be.

No new org chart on a PowerPoint document by itself has changed how people work. Done only in this way, as it sometimes is, the new documented Procurement operating model will lie in a cupboard and gather dust. And people will carry on largely as before. The biggest and most common mistake people make is not paying any attention to the next step, which is how to operationalize your new model. How are you going to get to where you've identified that you need to go? The answer is that you need to organically grow into your to-be model from where you are today.

One big reason the transition to to-be can be so hard is that Procurement can sometimes be a very reactive function. And when it creates a new model to work to, the implementation of that model involves Procurement doing a lot of things differently. But to do things differently it needs to have the time and space to be proactive, otherwise it won't be able to stop reacting to the same less value-adding activity that keeps coming from the business in the as-is model.

The business is not going to suddenly start treating Procurement differently on its own. This less value-adding activity could be new supplier requests from the business, urgent contract renewals, operational supplier management (part A has not arrived in warehouse B from supplier C—call Procurement pronto!), being brought into a supplier negotiation at the eleventh hour when it's almost impossible to affect the outcome, and a whole host of other activities. I'm sure at this point any seasoned CPO could come up with a list of 20 or more reactive activities his or her function has got stuck doing in the past.

Just how reactive is Procurement in general today? Well, we have seen studies across a number of industries and sectors that revealed Procurement self-scored that approximately 30% of its work was proactive and strategic versus 70% reactive and minimally value-adding. But if you scratch beneath the surface the true picture is likely to be a lot worse. This is, in fact, the best-case scenario since it was based on the number of strategic roles versus operational roles that exist in Procurement today, amongst those surveyed, and assumes that everyone in an operational role is reacting to business demands and that everyone in strategic roles is being proactive and strategic, all of the time.

The first assumption is fair, the second less so. How many strategic Procurement managers in your business can say they never get dragged into reactive, operational-type work? Or work where no particular skill was required? How many can say it doesn't even happen 50% of the time? Not many, I'd guess!

I was speaking to a client recently, discussing this exact point. He has five strategic Procurement managers in his team that he described as all doing strategic activity 100% of the time. But it turns out that all of them do contract renewals as part of their roles. And some of these renewals are entering the third or fourth renewal in a mature relationship where value is harder to come by at the renewal stage. It was actually someone in his team who piped up during our conversation with this point! This type of contract renewal is not really that strategic at all.

The true average percentage across industries is likely to be 10–20% of Procurement's time spent doing proactive, strategic activity today—activity it wants to do in order to change its operating model and significantly increase value proposition to the company and then maintain it. And that's not a lot of time!

Just to be clear, being proactive is not just a nice-to-have to help Procurement feel good about itself. It is absolutely critical to the survival of the function itself! This is because sooner or later this reactive and lower value-adding activity will be automated or done elsewhere in the business if Procurement is perceived as a bottleneck, which it can sometimes be. Procurement cannot afford to wait for this to happen. It needs to orchestrate the change and reposition itself before this is something that happens to Procurement. See Chapter 10: Technology, for how we think Procurement must learn from the plight of high street real estate agents in this regard!

Given this prognosis, how much activity that a Procurement function does should be proactive and strategic? Well, even if we assume that we are around the 15–20% mark today, we should aspire to 100%. But to get there requires you to take your function on a journey to its new to-be operating model. Below are the necessary steps.

Organic Growth to a Proactive Focus

Step 1: Visibility of work

Once your to-be model is designed, agreed, and signed-off, the first critical step is to get visibility of the work of your current team. Do you really know how each of them spends their day? Even the best CPOs might not at a granular level. Yes, Jessica might be running three strategic projects, but does she only spend her time doing that? Or are there other activities that keep her from focusing on what you'd like her to do? And the six tenders that Dermot has on the go—why are they taking so long? Is all that activity really strategic? Or is he spending large swaths of his time dealing with ad hoc requests from the business to contract suppliers with whom they have already negotiated?

A time study of your team is a valuable approach to understanding, at a granular level, what your team spends its time doing. By asking them to log their activities at frequent time intervals over a period you can aggregate the data and categorize it by activity type.

With this analysis—which is likely to surprise you—you can identify the work they are doing that you would like them to do (which helps move you towards your to-be model) and that which you would prefer they didn't. The latter being all the ad hoc and less value-adding work, or work you didn't even know about.

You will also be able to get a picture of the true scope of your function, which has probably not been visible to anyone in the business until now—at least not outside of Procurement. Of course, there will be a documented scope somewhere, but that is worth little if the reality is different.

I once worked with a Procurement function in which the consensus amongst people outside the function was that the vast majority of time was spent doing contract renewals and negotiating deals with some of the largest strategic vendors. But, while they did indeed do these things, a time study revealed some of the supposed key workers spent less than 20% of their time on these tasks and the remainder of their time: enforcing the company's mobile device and travel policies, maintaining an insurance tracker for the business and its plethora of business units to ensure each had the right cover, maintaining a large central register of office locations across the group for the many buildings it owned and leased, chasing the business for contracts to ensure compliance to regulation, coordinating the onboarding of suppliers with the business to ensure they met the relevant information security requirements, and chasing current and former suppliers to check adherence to the new General Data Protection Regulation that had just been brought in.

This sort of scope is more obviously less value-adding. But going back to our earlier example, on something like contract renewals, even part of supposedly strategic work can itself be less value-adding. Particularly if poor data and systems exist that call for hours of manual data manipulation.

No one is saying that you can just give up this sort of less valuable scope right away, but it is important to know your starting point accurately before piling more and different scope onto an already stretched team to get to a new to-be model. That is how the operating model initiative will fail.

The granular time study can be a one-off exercise, but another key outcome of this Step 1 on creating visibility of work is a dynamic view of what people are working on, at a slightly higher level, refreshed regularly. What initiatives are they working on? What is the expected benefit of those initiatives, and what are the expected timelines? You want to be able to review this regularly, as things change. Because without that, you can't take the next step.

Step 2: Start prioritizing

And that next step is prioritization. Really effective prioritization. To illustrate this, let's assume your Procurement team is maxed out doing unproductive work. Even if it is not, and it does some strategic tasks already, this methodology will still help you to reduce less value-adding work irrespective of how much is being done today by your team. Such work represents an opportunity to focus on more strategic and proactive Procurement activity that will help you progress to your to-be model.

To prioritize effectively, you need to ask probing questions of the current team and to get under the skin of what they are doing and why they are doing it. This requires a critical and questioning mindset towards current work mix. The types of questions to ask are:

- Are we triaging new requests effectively?

- Is the Procurement team working outside its remit and expectation?

- Can we enable the business to do more themselves?

- Are other teams a bottleneck (maybe Legal?)?

- Are we constantly reinventing the wheel?

- Are we using support teams effectively, if they exist?

With visibility of work created in Step 1, you can begin answering these questions.

And with these answers you can start to make some small tweaks to how things work and deploy some enablers. These enablers should help to provide some of the solutions to the issues thrown up by answering the previous questions.

Enablers can come in many forms: knowledge injection, specific skills, potentially even a new tool to automate or facilitate a task, if done correctly. For example, maybe we found in Step 1 that analysis of supplier bids saps time from the team due to manual reconciliation of bid sheets and then needing to build and run formulae to calculate possible supplier award scenarios. If that is the case, one enabler could be to create a standard approach to this analysis and build a template with a level of automation. Or let's suppose that three sourcing initiatives don't seem to be moving past the strategy phase because the business can't decide what commercial model it wants, creating a huge drag on three people's time in the team. We could buy in some external expertise to help run through options with the business in a day-long workshop to unblock this impasse.

If your team is maxed out—which it almost certainly will be whatever it is doing—then it's entirely possible you might need to find a short-term solution outside of your immediate team to do the prioritization task…a person able to find answers to the critical questions we discussed earlier. This is not a long- or even medium-term solution.

The principle should be build, transfer, operate; and then those tasks should be conducted within your own team as soon as possible once the first bit of time is freed up for it. Enablers should also be brought into your current team where possible but, in reality, there is likely to be a mix of internal and external enablers. For example, you may choose to outsource market research to support your sourcing strategies rather than have your team all try to do market research themselves in different ways. Or you might engage with an expert network that gives you access to category insight that allows you to unblock category strategies in the way we described earlier.

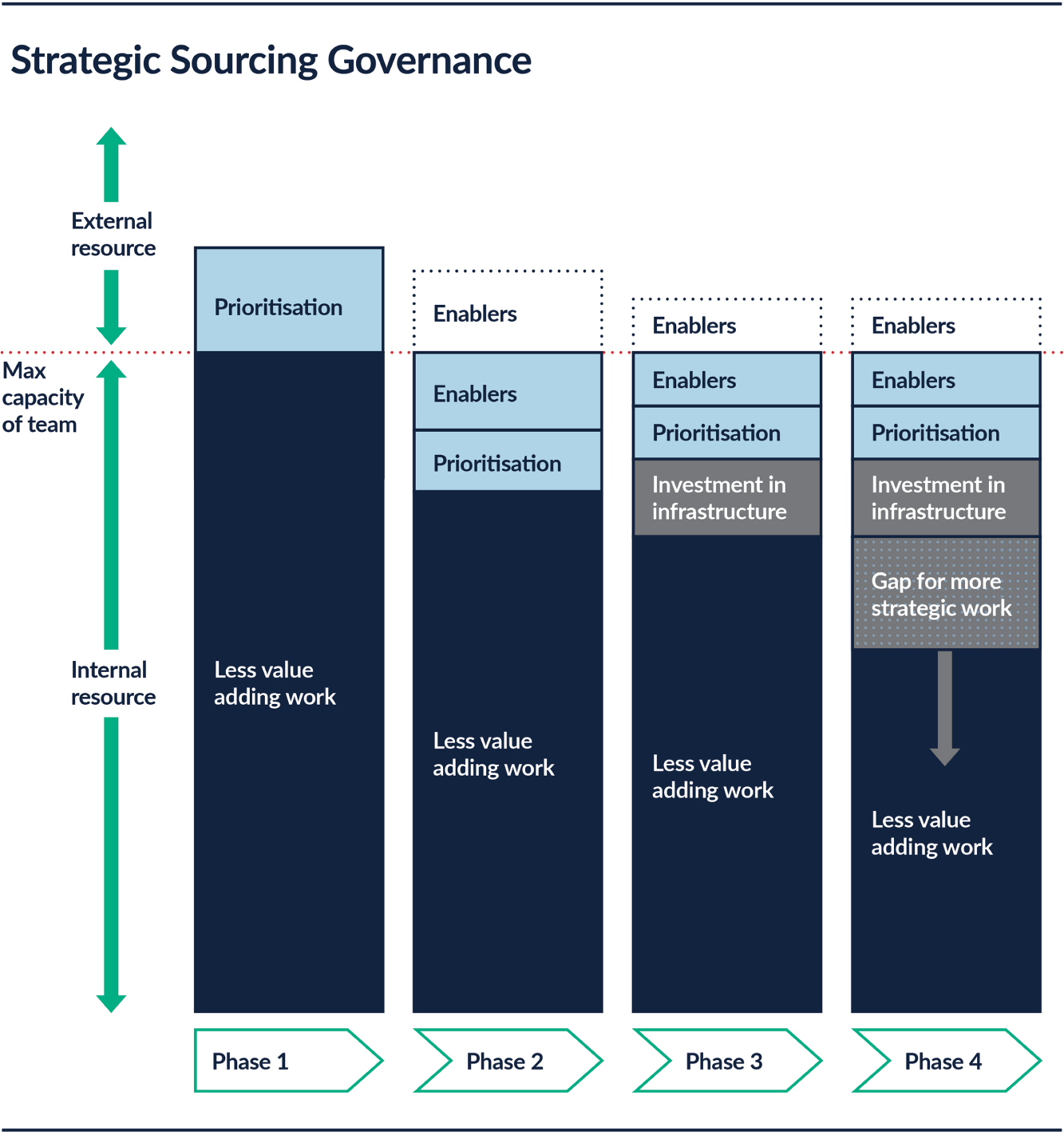

Figure 5.2 illustrates this process. And we have just spoken about moving from Phase 1 to Phase 2.

Figure 5.2 Strategic Sourcing Governance

The aim of this prioritization step is to get to Phase 4, which is where a gap in your team's capacity starts to appear—a gap that you can fill with new, more strategic activity and help you get to your to-be operating model!

But before we move to that, how to get from Phase 2 to Phase 3? The answer is, as soon as your inhouse Project Management Office (PMO) and enablers help you to free up capacity in your team, you should resist filling it with strategic activity straightaway. If you do, then that will be the limit of the strategic activity you will be able to manage going forward. Better is to use that freed up time to find ways of freeing up yet more time. We are calling this an investment in infrastructure, but what does this mean?

Well, it's similar to how we got from Phase 1 to Phase 2, but these are probably the first workstreams on your to-be implementation plan. For example, building a library of templates for people to help them do Strategic Sourcing more effectively in the future or building a knowledge management capability to ensure there is less reinvention of the wheel. When someone has strategically sourced the Chemicals category, how do we ensure that the prices, the suppliers, the strategies, and tender documents are all easily accessible and useable next time? By investing in this infrastructure, you are going to make further capacity gains going forward as you're helping your team be more effective.

Once we're at Phase 3, we will start to see those capacity gains grow, and we'll get to Phase 4. How we use that gap is now critical. And we need to be realistic here as well. If we have the same team with the same skills as before, then parts of the team might get exposed with the new demands for more strategic work. This is where the people part of your operating model comes in, and we discuss that in detail in Chapter 4: People. Ensuring you have the skills in your team to handle and excel at the new type of work you want it to do is, of course, just as critical as freeing up your team to do it.

Step 3: Build and maintain a hopper of opportunities

To ensure we use the extra capacity productively, we need to know what we are going to do with it. This means building a hopper of opportunities—a hopper of strategic activity for which there is a strong value proposition. These opportunities can vary in nature. They may be Strategic Sourcing opportunities; they may be opportunities for better supplier management. Perhaps opportunities for further bettering the infrastructure that exists to make the Procurement function yet more efficient and its people yet more effective. But before getting onto the hopper, let's clarify what is happening to the less value-adding work in this methodology.

Some of this less valuable work disappears, due to people being able to work more effectively through the enablers of technology, knowledge management, and better prioritization, as we have described here. But as Procurement starts to move towards its new model, it will also be able to better segment its workforce into those who do strategic work and those who don't. The diagram and this methodology become important for the team that is left doing the strategic work, and the less value-adding work can be passed to a more dedicated administrative sub-team or, in other cases, pushed back to the business.

Back to the hopper. The hopper is critical because it also allows Procurement to be flexible and agile—and especially in the face of a crisis such as COVID-19. With time freed up and a portfolio of strategic tasks ready to deploy that are proactive, Procurement can decide what it needs to work on to best serve the business. But, critically, with this visibility it also understands the opportunity cost of not doing certain activities.

When I was working with a UK-based client in the Leisure and Tourism industry in 2020, we had been able to transform its operating model during the previous 18 months to focus on more value-adding and strategic tasks, such as getting more value from critical suppliers and reducing supply chain risk. We were also doing a number of Strategic Sourcing activities. When the COVID-19 crisis hit, the business was impacted severely. All its locations had to close for months, due to government restrictions on staying away from home, and some of the longer sourcing activities the company had been doing were no longer a priority. What was important now was cash preservation. With no revenue to speak of for the foreseeable future, strategically sourcing consumer type categories was a complete irrelevance.

But, because there was a hopper of opportunities, it was able to delve into that during a time of crisis and act quickly in the interests of the company. Pushing out supplier payment terms without putting those businesses in danger became a number one priority. But, because we had an opportunity long-list, some pre-crisis activities continued. In short, the team was able to quickly pivot to the most value-adding portfolio of initiatives for the time because it had a holistic view of all opportunities and benefits.

Isn't This Just Agile?

Well, isn't it? I suppose the answer is, “Yes.” The moral of this chapter is not to simply identify where you are and where you want to go and document then the entire, long path to get there. That is the classic approach that can end in Procurement functions never really changing what they do, because you can't possibly predict that path.

If you want to ensure you successfully achieve a new Procurement operating model, you need to identify where you are and where you want to go, but then start to feel your way there, organically. You need to be comfortable stepping out on your journey to the to-be model, able to see the destination but not the whole path. If we jump back to Step 2 of this chapter's three-step methodology, the key is not to ask your people to start “doing more Strategic Sourcing” or “executing better supplier relationship management” to achieve a new operating model, but rather to figure out how to give them the time to do these new activities. Work together to figure out the path.

An absolutely key element of agile in Procurement is having the flexibility to chop and change what you are working on. And that is why a fundamental principle of designing a new Procurement operating model is to ensure you have a team that can be versatile, just like we discussed in Chapter 4: People. Any new, to-be model needs to avoid fixed roles, if at all possible—which is to say, a role in which the person only focuses on one type of activity or category. That is a thing of the past. An agile, and therefore successful, Procurement function needs people who can work across activities—people who can move from one opportunity in the hopper to the other as the business need dictates. That is how you will achieve your to-be model.