Innovation Through Investment in People: The Consideration of Creative Styles

The formation of a problem is often more important than its solution, which may be merely a matter of mathematical or experimental skill. To raise new questions, new possibilities, to regard old problems from a new angle, requires imagination and marks real advance in science. (Einstein & Infeld, 1938)

Progressive companies are generally interested in increasing the number of “good” ideas coming from their staff. This has traditionally been done by training individuals in idea-generation methods rather than by providing direct support for those individuals who have demonstrated a capability of generating ideas. The assumption has been that with an increase in the number of ideas generated, a concomitant increase in “good” ideas would result. Thus, companies have placed their emphasis on idea generation, and problem-solving sessions have most frequently been conducted with managers and those professionals who interface well with management. This is a natural tendency, as people tend to affiliate with those individuals who are similar to themselves in outlook and orientation. However, this may not be the best approach. An alternative might be to target those individuals who are creative and nurture their development. Instruments such as the Kirton Adaption-Innovation Inventory (KAI) may offer assistance in this endeavor (see Kirton, 1976, 1989; see also Kirton’s article, “Adaptors and Innovators: Problem-solvers in Organizations,” in the present volume).

The KAI was designed to measure a person’s creative style. The instrument does not measure one’s intellect or creative capacity but one’s creative style. Creative capacity and potential are most commonly measured in terms of one’s past performance. “Creative style,” on the other hand, is defined as the manner in which a person interacts with his or her environment when solving problems. Kirton’s model for creative style places people on a continuum between “adaption” and “innovation.”

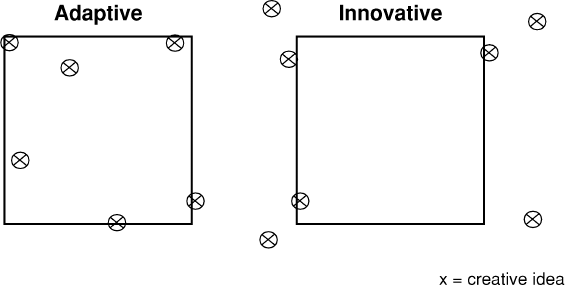

Adaptively creative people “operate cognitively within the confines of the pattern in which a problem is initially perceived. Their creativity is less likely to challenge existing frameworks” (Gryskiewicz, 1982). By contrast, innovatively creative people approach problems in a different fashion. These individuals are “more likely to treat patterns as part of the problem. The problem is redefined and results in a creativity style that goes outside of the original problem definition” (Gryskiewicz, 1982). These two styles are visually illustrated in Figure 1. The box symbolizes an original problem or the confines of a company. An innovatively creative individual is predisposed to look for solutions to problems or new directions for his company predominantly outside the confines of the box, whereas an adaptively creative individual will generally create within the confines of the box. Both individuals are creative. The Inventory describes one’s predisposition to a style of problem solving.

In other studies and workshops conducted by Kirton (1981), people have discussed the implications of their style in the workplace. For example, individuals with scores high on the innovative end of the continuum expressed the following views. They felt that: (1) They didn’t fit in; (2) they had their own personal agenda which may not appear relevant to the organization; (3) they had a low tolerance for adaptors; (4) it was hard to get positive recognition in big organizations; (5) ideas were stolen by bosses; (6) they needed a translator so others could understand them; (7) they hated to write; (8) they found it hard to get along with people above; and (9) they lost interest in working on a project once the end is seen.

Kirton (1977) also examined the view of adaptively creative individuals towards the innovatively creative individuals and the reverse. Adaptors perceived innovators as being neurotic, extraverted, extrapunitive, and inner-directed, whereas innovators perceived adaptors as being stodgy, timid, or compliant.

Both the innovatively creative and the adaptively creative individuals serve important functions. It would be wrong to assume that only innovatively creative individuals should be valued. Both groups have specific and necessary functions in large corporations.

The work summarized above led us at the Research Laboratories of Eastman Kodak Company to hypothesize that those individuals who submit idea memorandums (IMs)1 to the Photographic Divisions’ Office of Innovation2 would have an innovatively creative style, as measured by the Kirton Inventory. It was also hypothesized that the styles of submitters and their management would differ, with management being more adaptive given the nature of their role within the organization. We decided to examine the validity of these hypotheses.

Method

Letters were sent to all individuals (professionals, technicians, and managers) who had submitted IMs prior to and including 1981. Accompanying the letter was a copy of the KAI and a request that individuals complete and return it to the Office of Innovation. In exchange for completing the inventory, their scores were returned to them with a complete explanation. For purposes of this study, managers were defined as individuals who supervised five or more professionals within the selected divisions. Also included were managers who had not submitted IMs. Four groups were thus included: (1) professionals submitting IMs, (2) technicians submitting IMs, (3) management submitting IMs, and (4) management not submitting IMs. As this was a limited study, not all possible groups were included (i.e., professionals and technicians not submitting IMs were excluded).

Instrument

The KAI contains thirty-three items derived from observations and intensive interviews with managers, as well as from a literature review on creativity. The respondents use a five-point rating scale to indicate how easy or difficult they would find it to present themselves in this manner for prolonged periods of time. In scoring the KAI, scores may vary between 32 and 160 (see Figure 2, p. 82). The mean score for the normal population is 96.

Results

Table 1 indicates the population size and corresponding return rates of individuals on the KAI by company position and IM submission rate. Eighty-two percent of those individuals submitting IMs responded to the KAI, as did over ninety percent of those individuals submitting three or more IMs. It should be noted that there was great variability in population size. For example, the population of managers not submitting IMs contained thirty-four individuals, whereas the population of managers submitting IMs contained only eight. The subset of managers submitting three or more IMs contained two individuals. As would be expected, there was a larger group of professionals (111) and technicians (18) submitting IMs.

Table 2 contains summary data classified by position and IM submission rate. The numbers in the table indicate raw scores on the KAI. A quick glance at this table indicates that: (1) The mean score of managers and professionals submitting IMs was quite comparable (114 for managers and 115 for professionals). (2) The mean score for managers not submitting IMs was more adaptive, as indicated by the score 103. (3) The mean score for technicians submitting IMs was also more adaptive (105).

Table 1. KAI: Population Sampled and Return Rates by Position and IM Submission Rate

Table 2. KAI: Summary Data by Company Position and IM Submission Rate

These data are represented graphically in Figure 3. As would be expected in a research lab environment, the distribution was skewed to the innovatively creative side of the Kirton continuum with a mean score of 113 and a standard deviation of ±16.

Testing the assumption that individuals who submit a large number of IMs were more innovatively creative in style than their direct management, the data on individuals who had submitted three or more IMs were examined. Managers and professionals submitting three or more IMs both had a score of 124. Technicians submitting three or more IMs had a mean score of 122. Graphic representation of these data is shown in Figure 4. The mean KAI scores for managers not submitting IMs was 103 (see Figure 5). This was significantly more adaptive than the mean scores of the total group of individuals submitting IMs.

The use of the KAI indicates that the styles of those individuals submitting IMs, both managers and professionals, were quite comparable. This implies that individuals with innovatively creative styles assume many different roles at Kodak. These results also indicate that the KAI score of managers not submitting IMs was more adaptive than those submitting them. The KAI test scores for the managers (IM and non-IM submitters, mean score = 106) are not unique to Kodak and can be cross-validated by a data base described by Kirton (personal communication, 1982). In a random sample of 256 R&D personnel (Keller & Holland, 1978) and 90 R&D managers (Gryskiewicz, 1982), the KAI mean scores were 101 and 104, respectively. Taken at face value, the comparison of the Keller and Holland (general R&D personnel) and the Gryskiewicz (R&D managers) data suggests that managers have a more “creative style” than their staff. The Keller and Holland R&D personnel sample cannot, however, be compared to the Kodak sample because the professionals and technical personnel in our study represent a selected subset of Kodak R&D personnel (i.e., IM submitters only). Within the Photographic Divisions of Kodak Research Laboratories those individuals submitting three or more IMs had an average KAI score of 124, which suggests an operating style that is very different (i.e., more innovatively creative) from that of the majority of management tested.

Conflicts

Many adaptively creative managers and those IM submitters with high “I” scores may have conflicts with one another. Those things which adaptively creative individuals value (such as structure, continuity and predictability) may be at odds with the variation, extra energy, and desire for change which the more innovatively creative individuals need. When such an individual generates an idea outside his assigned line of work and brings it to his more adaptive management, it is often viewed as an annoyance. It does not fit into the structure within which the manager operates. In turn, the manager’s response leads to frustration on the part of the innovator.

A Relay Team Approach

The data in addition indicate that many individuals with innovatively creative styles like to start projects but do not necessarily carry them through to completion. Individuals with scores in the 126–137 range stated that “if there are too many of us, nothing gets done,” they “stop once the end is seen,” and they “hate to translate thoughts into written words.” On the other hand, individuals with more adaptively creative styles expressed continuity, dependability, and stability as advantages of their style. Again, conflicts may arise due to these differences. What compounds this problem even more is that individuals in the 106–116 range say they “see both points of view.” Therefore, they may not understand why others with more innovative scores cannot follow through. What is recommended is a team approach which combines the skills of innovatively creative individuals generating ideas with the follow-through skills of those with more adaptively creative styles.

Suggested Changes

Several structural and procedural changes are suggested by an acknowledgement of differences in creative style.

Team building can be conducted, taking into account both style differences of the individuals and the kind of outcome desired of the team by the organization. If a radical outcome or solution is needed, the adaptive-innovative mix and interplay can be different than if the outcome sought is to be an incremental improvement.

Ideas from innovatively creative individuals can be bubbled up to management. Adaptively creative individuals have an outlet for their style; they form the mainstay of the present organizational structure and are predominantly responsible for the present and near future income of the company. Innovatively creative individuals, however, lack an outlet. Both the innovator and the company suffer if one is not found.

An environment filled only with adaptors may result in stagnation, whereas one consisting solely of innovators may result in lack of visible productivity. In a large corporation it is necessary to utilize those individuals that see into the future in order to explore areas for potential diversification.

Management has an obligation to grow and, therefore, needs to put in place the means whereby the creative talent of their people is tapped for the kind of ideas that will allow growth: You’re betting on people to provide the spark that will ignite tomorrow’s fire, which in turn will have to be managed if it is to get anywhere.

In a small company a special conduit for ideas is usually not necessary because the entrepreneur is frequently both a manager and an innovator. Also, in a small company the entrepreneur is not far removed physically from those employees generating ideas. Another characteristic of small companies that affects innovation is the lack of a large middle management “filter.” Large companies have several levels of filter which make it difficult for ideas to get to the decision level of the corporate structure. In large companies it is generally not a prerequisite for a middle manager to be an innovator. What makes sense in larger, more bureaucratic organizations is an innovation system which provides a legitimate channel for ideas to bypass many of the unnecessary filters. The system also decreases the amount of time it takes for an idea to reach the proper decision-making body.

As technological trends develop, management can use channels such as an Office of Innovation to elicit related ideas from innovatively creative individuals. Since a difference in style exists between IM submitters and those managers who do not submit IMs, an innovation system must be designed to meet the needs of both. A facilitator of an innovation system needs to be able to relate to the range of creative styles (from adaptive to innovative). The facilitator thus becomes a bridge between the innovatively creative group and its usually more adaptive management. This would improve the flow and implementation of ideas, without style acting as an impediment. Management could use “idea ticklers” (i.e., a newsletter indicating areas in which upper management is interested in soliciting inventions) to inform potential inventors of current interest. As inventors become actively involved in the growth of the company, they will feel that they have a greater share in the company’s future. This should reflect itself positively in increased productivity.

Invest in people, not ideas. There are many possible ways to “invest” in creative people. These include eliciting their ideas in a personal fashion, helping idea-originators to develop and evaluate their ideas, and educating them as to how to get their ideas implemented (i.e., become product champions). What is needed is a program which identifies and invests in those creative, innovative individuals within a company irrespective of their personality traits and work styles. A final and difficult way for managers to demonstrate such investment is to sustain the commitment to individuals when a specific idea doesn’t happen to pan out. The organization must keep in mind that some day one or more of these individuals may come up with the big idea that becomes the backbone of the company’s profitability for years to come. By investing in these individuals, management is also creating and maintaining a climate for creativity. People will then more freely offer their ideas. Out of these, the so-called good ideas will emerge.

This approach reflects a subtle difference in emphasis but one which may make the difference between future success and failure in a quickly changing economy. Garnering good ideas can be accomplished in various ways. One way is through the use of a suggestion system. This approach can be likened to searching for rose blossoms in a field. The wild rose bush has many prickly branches and very few perfect blossoms. Investing more directly in creative people is like domesticating and cultivating roses in a garden. By carefully tending the garden one produces the best flowers, and by picking the plant frequently, one gets more flowers of higher quality. As with the garden, if creative people are carefully tended, they will develop. If their ideas are not evaluated properly, innovatively creative people will decrease the production and quality of their novel ideas. It is not the plant’s responsibility to cultivate itself; it is the responsibility of the gardener.

Develop acceptance of the diversity of creative styles. A vehicle such as an educational program is needed to enable both groups to see their value to the company and to each other. A useful way of visualizing the relationship between innovatively creative and adaptively creative styles is “contained disorder.” It’s like the core of a nuclear reactor. If the internal disorder is allowed to run rampant it will destroy the reactor. Its containment, however, allows one to harness its energy and produce a balance. Adaptively creative individuals, which form the bulk of an organization, are like the reactor, and innovatively creative individuals are like the reaction within it. They need to work in harmony for the benefit of the organization.

Notes

1An IM is a written submission of an idea. An IM may be revolutionary or evolutionary. In either case, the idea is submitted to the Office of Innovation because it is outside the submitter’s assigned work.

2For more information on PDOI’s system and the role of the facilitator, see Rosenfeld (1981).

Acknowledgment

I thank Tom Whiteley, Director of the Emulsion Research Division (KRL), for allowing me to run this study and being supportive of the PDOI operation. I also thank Robert Bacon, my collaborator in setting up PDOI, for sharing his insightful approaches to people, and for inspiring me with his strong, long-term commitment to creativity and innovation. I am also grateful to Michael Kirton and Stan Gryskiewicz for being very cooperative in supplying the necessary data and allowing me to use the inventory. I am most grateful to Jenny Covill-Servo for her patience and time spent in putting together this paper and for sharing her statistical expertise and her understanding of different cultural interactions which supplied additional insight in looking at the creative style of individuals.

Finally, credit is due to those creative individuals for their trust, for their patience in working with PDOI, and most of all for sharing themselves.

Bibliography

Einstein, A., & Infeld, L. (1938). The evolution of physics; the growth of ideas from early concepts to relativity to quanta. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Gryskiewicz, S. (1982). Creative leadership development and the Kirton Adaption-Innovation Inventory. Paper presented at the Occupational Psychology Conference of the British Psychological Society, Sussex University, Brighton, England, January 6, 1982.

Keller, R. T., & Holland, W. E. (1978). Individual characteristics of innovativeness and communication in research and development organizations. Journal of Applied Psychology, 63, 759–762.

Kirton, M. J. (1976). Adaptors and innovators: A description and measure. Journal of Applied Psychology, 61, 622–629.

Kirton, M. J. (1977). Kirton Adaption-Inmvation Inventory (KAI)—Research Education. Winsor, UK: NFER Publishing Company, Ltd.

Kirton, M. J. (1981). Workshop conducted at Creativity Week IV. Center for Creative Leadership, Greensboro, North Carolina.

Kirton, M. J. (Ed.). (1989). Adaptors and innovators: Styles of creativity and problem-solving. Routledge: London and New York.

Rosenfeld, R. B. (1981). The development and philosophy of the Photographic Divisions’ Office of Innovation (PDOI) System. In S. S. Gryskiewicz & J. T. Shields (Eds.), Creativity Week IV, 1981 (pp. 105–139). Greensboro, NC: Center for Creative Leadership.

~~~

I first met Bob Rosenfeld more than fourteen years ago, when he was beginning to wrestle with the problem of bureaucracy and organizations. He continues to confront the difficult issue of growing and connecting ideas inside organizations, and he has formed a company called Idea Connections Systems, Inc., through which he takes the skills he developed at Kodak into a variety of organizations. Always a champion of the individual, Bob is especially interested in exploring systems that generate trust among co-workers and nurture the development and implementation of the ideas of these individuals. Bob’s interests have also taken him into the international arena through the United Nations. In this work he tries to alleviate racist attitudes toward minorities. Ever the optimist, he continues to do what it takes to live a life driven by his values. SSG.