The Customer-Centric Enterprise

Management Overview

Creating, and sustaining, a truly customer-centric enterprise requires both focus and dedication in a number of key areas. Some are strategic, and some are tactical. They include process, messaging, and optimizing experiences. This section addresses concepts, priorities, and initiatives that can be applied in several of the most important areas.

Employees and Processes

Beyond employee engagement which, conceptually, is largely about alignment with, and commitment to, both the enterprise’s goals and its value proposition, customer-centric organizations will want to focus on commitment to customers (understanding their needs, and performing in a manner which provides optimal experiences and relationships). So, with respect to hiring, training, and evaluating for motivation, cohesion, and productivity, the forward-looking and customer-centric enterprise will want to focus on employee ambassadorship. Ambassadorship has proven to leverage stronger staff loyalty and customer value. In addition, the benefit of employee research will be operationally enhanced by not only identifying drivers of employee satisfaction and engagement, but also determining what will create stronger and deeper levels of ambassadorship. As one critical product of ambassadorship, it has been proven that employee advocates have higher levels of loyalty to their organizations.

Strategic Customer Focus and “Roadmap”

Paraphrasing Lewis Carroll’s Cheshire Cat in his advice to Alice, that is, “If you don’t know where you’re going, any road will get you there,” the lesson for organizations is that a strategic orientation is needed in the design and execution of customer experiences. Additionally, value propositions should be well defined, and communication and marketing should be consistent. Finally, the customer-centric organization will have definite focus in product and service programs. In following this strategic customer-centric “roadmap,” the organization must be able to have a tangible and emotional value proposition for customers. It must understand what customers want and identify how customers “learn” and make product and brand decisions. It must involve customers in product and service design, and also in development and messaging. It must have the culture, structure, and processes for truly valuing customers; and, as part of this orientation, employees must become ambassadors for the customers and the company’s value proposition.

Role of the Chief Customer Officer

Companies endeavoring to become more customer-centric, or to sustain a customer-centric culture have, increasingly, entrusted the execution of optimal customer experience and relationships to a Chief Customer Officer, or CCO. Functioning at a senior corporate level, the CCO role is to define and lead delivery of the value proposition across the array of communication and transactional touchpoints. There are, arguably, five core areas of responsibility for the CCO:

• Customer experience and value optimization

• Customer insight, data, and action generation

• Customer relationship-building

• Customer journey management and life cycle strategic consultation

• Customer-centric culture leadership and liaison

CCOs will have backgrounds that include sales, service, strategy/innovation, customer experience, product development, and customer and brand research.

Building Trust for Stakeholders Within the Enterprise

Trust has become essential for organizations, both at the individual employee level and at the enterprise level. Trust is about being honest, keeping promises, building stakeholder partnerships, and creating a positive and memorable customer experience. It is shaped by executives and managers, who, hopefully, also contribute to its continuity as a living force within the organization. It is a foundation element in building and sustaining customer relationships, and in leveraging customer behavior.

Customer Partnering

Partnering is, as noted above, building stronger relationships between customers and the enterprise. It facilitates a deeper knowledge and understanding of customer needs, and is essential to building value for them and cementing the relationship. The concept of partnering has been practiced by organizations for hundreds of years, and has received much more emphasis since the beginning of the Total Quality movement. Bringing customers and channel partners into the center of the enterprise enables first-hand sharing of ideas, leading to innovation and stronger product and service value.

There are many variations to the concept of customer partnering. One actively cited in this section is Intuit, where “listening posts” have been set up around the company; and, customer interaction touchpoints represent opportunities for problem resolution and new product development. Intuit works with major financial institutions on a team basis.

In generating stronger customer partnerships, organizations should ask if they understand how their customers perceive advantage, solution, and benefit, how customers do business with them, what is known about competitive offerings, and what is unique (or can become unique) about the organization.

Addressing Customer Complaints, Part 1: Using Social Media to Protect Brand Equity and Customer Loyalty

Identifying the full range, or inventory, of customer complaints—and proactively, and positively, addressing and resolving them—is an extremely important element of managing value in the overall experience. However, utilizing “complainer personas” for those posting negatives about their supplier transactions or relationships does not recognize the fact that online complaints are not representative of the overall customer base. Acknowledging that, though representing a small percentage of the customers, these negative postings can do a lot of reputation and purchase damage; identifying types of complainers and how to respond to them will have limited effectiveness. Resources should be deployed to address and mitigate the individual and collective impact of customer complaints.

Managing Customer Experiences

Executives believe, overwhelmingly, that improving customer experience is a major priority; however, only about one-third had begun customer experience initiatives, and fewer still considered their programs well along. Further, though these executives felt that having strong social media leverage was important for building relationships, a high percentage have no social or mobile programs to support sales or service. Though it is recognized that better customer experiences will build loyalty, much of the investment by organizations goes into advanced technologies rather than enhanced value through more personalization, omnichannel service access, and social media integration. A customer experience success model identified as superior is that of Metro Bank in London, where optimizing customer experience is embedded into the corporate DNA.

Addressing Customer Complaints, Part 2: Getting the Whole Picture

Even though product and service loyalty levels continue to decline, for an array of reasons unhappy customers will often take their business elsewhere rather than complain to a supplier. Because such a small percentage of customers with complaints actually express them, even in business-to-business (B2B), it’s essential that organizations have a research and contact program to identify unexpressed complaints, as well as discern the level of perception with complaints addressed and resolved. Poorly resolved complaints are creators of risk and potential churn. Customers should be encouraged to make contact with questions or complaints, and they should be given sufficient contact channels. Root causes of all complaints, expressed and unexpressed, should be addressed and corrected. Having a full database of complaints facilitates both correction and stronger customer relationships.

Stakeholder Disengagement and Negativism

Organizational culture has the power to create both stakeholder advocacy and alienation, that is, positive and negative behavior, on its behalf. In the 1999 movie Office Space, clerk Milton Waddams is portrayed both as a disgruntled employee and a disgruntled customer. This reminds us that all stakeholders should be treated with fairness, inclusion, and respect—otherwise they can (and, as in Milton’s case, absolutely will) burn down the company—figuratively and literally.

Employee Retention, Engagement, and Ambassadorship Go Hand-in-Hand-in-Hand At Successful Companies+ (September 5, 2013)

Nearly all companies are concerned about employee turnover; and, with the worldwide economy in recovery, it has become a priority. In some industries—notably retail, customer service, and hospitality—annual staff churn rates of 30–40% and more are not uncommon, and even—considered acceptable. While this situation may be a reality in many companies, it isn’t a very sound strategy, and from multiple perspectives:

• The value employees can bring to customers is diminished

• The breakdown in customer–staff continuity and trust when employees leave

• The negative cultural effect of turnover on other employees

• The real “total cost” of losing employees, including hiring, training/coaching, productivity

So, retention has become a huge issue today. We should be concerned about it, of course; but we also need to focus on the degree to which employees who stay with a company are directly and indirectly contributing to customer loyalty behavior. Numerous studies have been conducted on elements of employee value, addressing reward and recognition, job fit, career opportunities, work environment, departmental and management relationships, and so forth. It is pretty much conventional wisdom that, during this period where there is great demand for exceptional talent, especially individuals who are diligent, innovative, and customer-focused, successful companies will also have loyal employees.

Twenty years ago, consulting organizations began moving away from employee satisfaction to employee engagement as a focus, on the theory that employees who were well trained, well compensated, aligned with the company’s business goals, and involved in the organization’s direction would be contributory and solid team players (Figure 1.1). That said, much of engagement research has not been able to prove (beyond incidental connection) that, while having happy and aligned staff is sufficient for somewhat higher levels of employee retention and productivity, engagement, in and of itself, only marginally contributes to optimum customer loyalty behavior.

Figure 1.1. Employee engagement.

One of the shortfalls too often seen in engagement, particularly as this type of research applies to optimizing customer experience, is that, even if employees are trained in brand image, this does not mean they will proactively deliver on the product or service value promise to customers or other stakeholders. Image needs to be integrated with building a culture of true, and even passionate, customer focus. In other words, the external brand promise has to be experienced by customers every time they interact with the company, especially its processes and its employees.

Can companies, through employee research and the insights this provides, learn how to prioritize initiatives which will generate optimum staff commitment to the company, to the brand value promise, and to the customers?

If employee satisfaction and employee engagement aren’t specifically designed to meet this critical objective, and only tangentially correlate with customer behavior, can a single technique provide the means to do that? The answer to both questions is: Yes, through employee ambassadorship research. Employee ambassadorship has been specifically designed to both build on employee satisfaction and engagement and bring the customer into the equation, linking employee attitudes and actions to customer loyalty behavior.

Employee ambassadorship, or employee brand ambassadorship, has direct connections to—yet is distinctive from—both employee satisfaction and employee engagement. As a research framework, its overarching objective is to identify the most active and positive (and inactive and negative) level of employee commitment to the company’s product and service value promise, to the company itself, and to optimizing the customer experience.

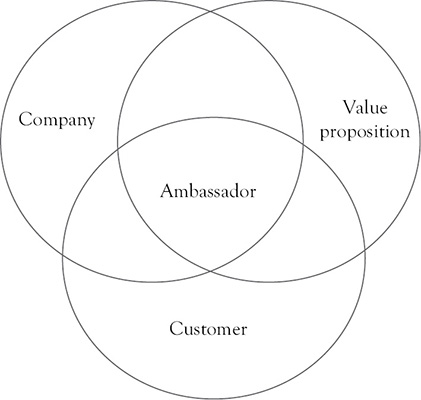

The ambassadorship thesis, with its component elements, can be displayed as in Figure 1.2.

Figure 1.2. Employees who score high on commitment to the company, the value proposition, and the customer are considered ambassadors.

• Commitment to company—Commitment to, and being positive about, the company (through personal satisfaction, fulfillment, and an expression of pride), and to being a contributing, loyal, and fully aligned, member of the culture

• Commitment to value proposition—Commitment to, and alignment with, the mission and goals of the company, as expressed through perceived excellence (benefits and solutions) provided by products, services, or both

• Commitment to customers—Commitment to understanding customer needs, and to performing in a manner which provides customers with optimal experiences and relationships, as well as delivering the highest level of product, service value, or both

Ambassadorship is very definitely linked to the productivity and empowerment elements of employee satisfaction, engagement, and alignment research; however, it more closely parallels achievement of business results and value building because its emphasis is on strengthening customer bonds through direct and indirect employee interaction.

In addition to employee motivation, cohesion, productivity, and alignment with corporate values and culture, Human Resources (HR) is perhaps most interested and focused on learning how to increase staff loyalty.

Staff research (among thousands of adult employees, in almost 20 different industry sectors) identifies employee loyalty level through three specific metrics: rating of the organization as a place to work, likelihood to recommend the organization to friends or family members as a place to work, and level of felt loyalty to the organization. Overall, in a major study of staff ambassadorship, 18% of respondents exhibited high loyalty to their organizations, and 20% exhibited low loyalty; and, importantly, there were strong, almost polar opposite differences in organizational loyalty depending on whether an employee was categorized as an ambassador or saboteur, validating ambassadorship framework results (see Table 1.1).

Table 1.1. Employee Loyalty* by Ambassador Group

|

|

Total |

Ambassador |

Saboteur |

|

Low |

19.8% |

0.0% |

61.0% |

|

Medium |

61.9% |

27.3% |

38.5% |

|

High |

18.3% |

72.7% |

0.5% |

|

Total |

100.0% |

100.0% |

100.0% |

*Comprises the three metrics used to calculate employee loyalty.

These are definite “pay attention” findings for HR. It’s a concern, of course, that almost 20% of employees have low organizational loyalty; however, it’s an even greater challenge that there are three times the level of potential staff turnover among saboteurs, who, before they depart, will undermine the performance and loyalty of other employees. This research provides very specific insights into why this is occurring. At the same time, the organization will be very well served to emulate the behaviors and attitudes of ambassadors through the rest of the culture.

Commitment to the company, in the form of loyalty and related attitudes and behaviors, is a fairly basic requirement for employee ambassadorship. Commitment to the value proposition and to the customer are parallel key elements of ambassadorship (which we will describe in future blogs), and our research has identified equally powerful results in these areas. What actions should companies be taking with insights such as these?

Here are several:

• Employees, at all levels and in all functions need to have a thorough understanding of what’s important to customers so that their actions match customer expectations and requirements.

• Employees’ behavior needs to be aligned around customer experiences.

• Management must build processes, technology, training, and organizational/cultural practices that support employees being able to optimize customer experience.

Perhaps most of all, companies should evaluate the effectiveness of rules and metrics associated with delivering customer value. For instance, how effective is the company, and employees, at unearthing and resolving unexpressed complaints which may be undermining customer loyalty? How are non-financial metrics viewed relative to financial ones? What types of automated support processes exist, and how well are employees trained in them, to make serving customers easier? How does the company balance taking care of existing customers, particularly those who may be at risk of defection, with acquiring new ones? How much cross-functional collaboration exists in support of the customer?

For companies to create and sustain higher levels of employee ambassadorship, it’s necessary to have customer and employee intelligence specifically designed to close gaps between customer experience, outmoded internal beliefs, and rudimentary support and training. It’s also essential that the employee experience, especially vis-à-vis customers, be given as much emphasis as the customer experience. If ambassadorship is to flourish, there must be value, and a sense of shared purpose, for the employee as well as the company and customer—in the form of recognition, reward (financial and training), and career opportunities.

“If You Don’t Know Where You’re Going [with Customers], Any Road Will Get You There,” Wisely Said the Cheshire Cat+ (July 20, 2013)

In paraphrasing Lewis Carroll’s famous conversation between Alice and the Cheshire Cat in “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland,” what I’m principally doing is calling out poorly designed and executed customer experiences, fuzzy value propositions, communication and marketing inconsistencies, unclear or nonexistent strategies, and an overall lack of focus too often evident in product and service programs.

Just as the Cheshire Cat asked Alice some important questions to help guide her way through a strange, unfamiliar land, here are some basic, critical marketing and channel questions for companies to consider in strategizing and managing the customer journey (Figure 1.3):

Figure 1.3. Companies should consider some basic, critical marketing and channel questions in strategizing and managing the customer journey.

1. Can your essential tangible and emotional business, or value, proposition for customers (expressed in the customer’s terms) be easily stated, that is, “Do you have a ‘why’ as well as a ‘what’?”

2. Who are your customers, who are your best customers, and do they want what you make available, that is, “Do you have a process for identifying, and analyzing, the reasons customers buy, or don’t buy, what you offer?”

3. How do your customers “learn” and make decisions, that is, “Where do they get product and brand information, how do they process and share it, and is it personalized for their specific requirements and needs?”

4. Are your customers involved in all phases of product, service, brand, communication, and marketing development, that is, “How much, and how well, do customers participate in the conversation, and partner and co-create on all elements of value and messaging?”

5. Do employees, irrespective of level or function within the enterprise, help you deliver perceived brand, product, and service benefit, that is, “Do customers see employees as ambassadors or saboteurs?”

6. Does the business—and everyone in it—have a passion, and sets of processes, for truly valuing, respecting, and cherishing its customers (and employees), that is, “Do you have a customer-centric culture?”

As a strategic, customer-focused marketer, the Cheshire Cat is a pretty reasonable and fundamentally logical character, even if the customer behavior realm in which he exists often is not: “You just go where your high-top sneakers sneak, and don’t forget to use your head.” Living in Wonderland, the Cheshire Cat understands the value of good planning, and getting intelligent answers to essential value proposition and brand equity questions; and he also appreciates the beneficial, and often elusive, forming and executing of customer strategies. As he notes: “Only a few find the way, some don’t recognize it when they do—some...don’t ever want to.”

Occasionally, just like in the Cheshire Cat’s mythical world, marketing, brand building, and experience programs can seem to vanish altogether, at least insofar as customers are concerned. The challenge for enterprises is to make sure that there is an end goal, or strategic set of value objectives, always in sight and mind for all stakeholders, and that everyone understands it. Remember how easy it is to stray off the right path, recognizing, as the Cheshire Cat sagely quoted: “Oh, you can’t help that. We’re all mad here.”

The Evolving Chief Customer Officer: Identifying Value, Authority, Scope, Responsibilities, and Strategic Direction Within the Enterprise+ (July 13, 2013)

In the past decade, we’ve seen the number of companies with an individual in the role of CCO—nicely defined by Wikipedia as “the executive responsible for the total relationship with an organization’s customers”—grow from under 100 to thousands today. Reflective of the escalating focus on customer data, experiences, and relationships across all methods of communication and access, the role is rapidly evolving and morphing; however, there is general agreement regarding its significance in building and sustaining true enterprise customer centricity.

The Chief Customer Officer Council has determined that the CCO role, in part because its requirements, authority, and scope are being constantly reworked almost in real time, has the shortest life span of any senior executive, with an average tenure of less than 29 months. While colleagues such as Jeanne Bliss, Tony Zambito, Maz Iqbal, and Bob Thompson, and consulting organizations such as Forrester, Aberdeen, and Strativity, have done much to flesh out the customer-centric contributions and responsibilities of a corporate CCO, what is becoming recognized is that the function requires greater education, understanding, and awareness of its benefits among C-suite executives.

In studies, articles and reports addressing how organizations build customer focus and customer passion, Forrester has identified that the CCO, serving at a senior corporate level, has (as reported by Paul Hagen of Forrester on the HBR Blog Network) “…the mandate and power to design, orchestrate, and improve customer experiences across the ever-more-complex range of customer interactions.” The function now exists in companies as varied as Dunkin’ Brands, USAA, Philips Electronics, FedEx, The Cleveland Clinic, Allstate, and SAP. And, where there is a CCO in place and working with other C-suite executives, the authority and scope associated with the position has direct influence over corporate customer experience priorities and application of resources.

Five Core Areas of Functional Responsibility

From my perspective, there are five core areas that identify the operating functional landscape, and contribution potential, represented by an effective CCO. They are as follows:

Customer Experience and Value Optimization

Studies by Strativity, and other consulting organizations, among corporate executives have identified the financial benefits of increasing customer experience management (CEM) related resources. For many companies, the brand-appropriate customer experience spans across multiple channels and touchpoints, and it can involve internal groups such as information technology (IT), sales, marketing, operations, customer support, new product or service development, and product management. Corporate reputation and image, and brand equity, also come into play; but, it is experience, and the resulting perceived value, which is the single biggest driving component of customer behavior.

For the CCO, broad background in customer experience optimization transcends the brand-building focus of marketing (the Chief Marketing Officer’s [CMO’s] role) or IT/operations (frequently the Chief Information Officer’s [CIO’s] role). CCOs must understand marketing, brand perceptions, and operations, of course, but their principal goal should be to deepen relationships, establish greater levels of trust, and build stronger customer loyalty behavior.

Customer Insight, Data, and Action Generation

Today, businesses are able to measure their activities, impact of customer experiences, and customer relationship with unprecedented precision. Many are actively collecting Voice of Customer (VOC) data through surveys, feedback management, analytics, and market research relating to customer retention, loyalty, brand equity, and satisfaction. As a result, they are able to create enormous streams and bases of data—known, collectively, as “big data.”

With the growth of the digital economy, where clickstream data and content are available through mobile communication channels, real-time insights into consumer behavior (through semi-structured and unstructured information) can be readily provided; and information management software and predictive analytics are available for virtually any enterprise. This is then combined, or integrated, with qualitative and quantitative customer research (in other words, it is not possible to gain a complete MRI of customer behavior without tactical and strategic research), especially in areas of customer need and behavioral segmentation.

Customer-related decision making is now knowledge-based, replacing intuition and guesswork. It is the CCO who leads, and is the focal point, in collecting information from inside and outside of the company, integrating and analyzing it for trends and clues, developing actionable results (such as identifying patterns of customer behavior), and, in a collaborative way, leveraging this material to improve experience performance and customer value.

Building insight, supportive data, and action which impacts customer behavior also involves inclusion and periodic debriefing of employees, for alignment and support of corporate customer-related initiatives.1

Customer Relationship Building

In this omnichannel world, maintaining proactive and positive relationships with customers, throughout the life cycle, is a key component of the CCO’s role within the enterprise. CCOs, in other words, need to be able to align and innovate engagement and relationship strategies. This requires a knowledge of, and facility with, the insights and metrics associated with perceived brand equity, and customer communication and experience as well. As noted, building and reinforcing trust, which leads to integrity and a strong relationship, is the goal here.

Relationship building, incidentally, also includes active involvement of employees in all customer-related initiatives, building the level of ambassadorship and contribution.2 There’s proven strong financial linkage between customer behavior and employee interaction and loyalty. Beyond just understanding employee satisfaction and what employees value and desire in their jobs, it is essential that companies have a research and analysis method which correlates staff performance to customer actions so that they can create project teams, and hire, train, recognize, and reward employees for how they contribute to customer value.

Employees are at least as important as other aspects of customer management in optimizing benefits for customers, and they frequently represent the difference between positive experiences or negative experiences, and whether customers stay or go. As research into this effect concludes with regularity, employee attitudes and actions, especially around customer commitment and engagement, and championing a company’s products or services, can’t be separated from the effective delivery of customer value. So, another skill set component of the CCO should be to both engage employees in customer-related programs, and effectively form and lead cross-functional project teams.

Customer Journey Management and Life Cycle Strategic Consultation

Organizations need to understand how elements of the customer experience journey, and the journey in totality, impact downstream customer behavior (including informal word-of-mouth). This is another key role and function of the CCO.

Further, the CCO’s operating parameters will include the complete span of a customer’s life. Just as relatively few companies have developed algorithms and processes for estimating lifetime customer revenue value, so also few companies truly comprehend how experience management programs have to be modified depending on the customer’s life stage. In their role, CCOs will see experience management as never-ending processes that embrace mutually beneficial and value-producing relationships for all customers, that is, past, present, and potential, and internal, intermediate, and external, creating not only enticements to become customers, but also barriers to exit or churn.

As we see them (and as fully described in Customer WinBack, a book co-authored with my colleague Jill Griffin), there are three major phases of a complete customer life cycle: Targeting/Acquisition, Retention/Loyalty, and Lost/Won-Back. And, though there is a great deal of flex in these phases (depending upon the type of business involved), adeptly managing customer value over the life cycle is a major responsibility of the CCO. The customer, and the customer’s loyalty, can never be taken for granted—a fact well understood, and driven into the organizational DNA, by the CCO.

Customer-Centric Culture Leadership and Liaison

The cultural role and senior-level influence of the CCO is continuing to crystallize, but is already extremely important. If an enterprise is going to have the right message to the right customer in the right medium at the right time, then for creating a top level of touchpoint experiences—and doing it profitably with the right organizational structure, with the right mindset—everything begins with data and ends with insight and action.

The continuing goal is to build and sustain (and repair, when needed) rock-solid relationships with customers and to make employees, at all levels and in all functions, ambassadors for delivering value. And, it needs to be accomplished in a financially feasible and responsible way. All of this is planned and directed by the CCO.

The Emerging CCO Skill Set

According to Forrester research (as recently reported by Bob Thompson), holders of the CCO position have rather diverse, and even fairly eclectic, backgrounds (Figure 1.4). Almost 90% come, in a pretty evenly distributed way, from operations/quality/process improvement, divisional senior leadership, or marketing; however, experience in sales, service, strategy/innovation, customer experience, product development, customer and brand research, and IT is also well represented. Ideally, the successful CCO can bring, and synergistically blend, many of the capabilities inherent in these varied functions.

Figure 1.4. Chief Customer Officers have diverse backgrounds.

Source: Forrester research interviews, news announcements, Google searches, and Hoover’s searches.

One survival factor that is, or will become, common to the continuity, scope, and authority of the CCO is the ability to demonstrate direct impact on revenue—acquiring attractive new customers, driving customer loyalty behavior throughout the life cycle (including reduced churn and more proactive complaint management), and lowering customer management costs. From the organizational side, and again quoting Paul Hagen, what C-suite executives should do to make the CCO position optimally effective is establish “…a strategic mandate to differentiate based on customer experience, a portfolio of successful projects that create buy-in and a cultural maturity in the organization, and a uniform understanding on the executive management team for what the position can accomplish.”

The Behavioral Impact of Trust: Peppers and Rogers on Trustable Companies, via Charles H. Green (June 30, 2013)

In my recent blog discussing the importance and leveraging value of trust, between individual stakeholders, between stakeholder groups within organizations, and between enterprises and stakeholders,3 I cited content I’ve seen on this subject by Don Peppers. I thought it would be useful to expand on that reference. For those who are interested (and I hope that is a lot of CustomerThink blog readers), please take a look at this 2010 interview by my colleague, Charles H. Green, noted consultant on enterprise and individual trust building and co-author of The Trust Advisor.4

Jeanne Bliss has also written frequently about various elements of enterprise trust-keeping promises, building partnerships among stakeholders, minimizing “rules,” creating a positive, holistic, memorable customer experience, proactively apologizing for mistakes, and so forth.5

My perspective on trust is pretty straightforward: Technology has created a world where we are witnessing, in real time, both the amount, and impact, of offline and online informal brand-related communication. Negativism in this context has the power to impair, even cripple, any brand or enterprise, both tactically and in strategic ways.

In trust research conducted by public relations (PR) firm Weber Shandwick, under the direction of Leslie Gaines-Ross, Chief Reputation Strategist, it was found that 70% of consumers surveyed avoid buying an organization’s product if they do not like the company making or selling it. For the financial and reputation realities of trust, just look at Global Crossing, Enron, British Petroleum, Toyota, Carnival Cruise Line—and, more recently, public figures like Lance Armstrong, David Petraeus, and Paula Deen, who have seen lucrative endorsements vanish.6

What Jeanne, Don, Martha, and Charles Green are addressing is how an enterprise, or an individual representing an enterprise, needs to be trustable in the extreme, that is, customer-focused, proactive, transparent, fair, and honest. Trust is a foundation element in building and sustaining customer relationships, and in driving strategic customer loyalty behavior.

In 2010, Peppers and Rogers saw creating trustability as the “next big thing.” It was, is, and will continue to be.

Customer Partnering: Proactive, Vital, Winning CEM (May 31, 2013)

In his thoughtful and incisive 1996 book, Customers Mean Business,7 James Unruh, former chairman and Chief Executive Officer (CEO) of Unisys Corporation, said: “…partnering with customers promotes a deeper understanding of customer concerns and of areas for improvement. Partnering relationships can create a seamless interface between an organization and its customers.”

Those are profound words; and, almost 20 years after the book was published, this continues to be a significant, and even basic, concept for any company endeavoring to create an optimal level of customer loyalty behavior for itself. Smart and evolved companies create value in partnership with customers (Figure 1.5), and value is as likely to come from people and information/content as it is from products and services. If companies practice new ideas, such as “creating interdependence” and “building equity” with their customers, they are strategically differentiating themselves from competitors. They are also creating “barriers to exit,” making it more difficult for their customers to leave and begin a relationship with a new supplier.

Figure 1.5. Smart and evolved companies create value in partnership with customers.

The idea of customer partnership is not new. Japanese businesses have used similar techniques for decades in process design and redesign. With the increase in customer focus, partnering has taken on added dimension in recent years. Companies like Chrysler actively use customers to help in the design of new vehicles. Southwest Airlines includes customers on teams involved in staff hiring. Preston Trucking, headquartered in Maryland’s eastern shore, has a Quality College, adapted from Japanese concepts, where customers, non-customers, and Preston staff have a forum to evaluate operating methods. Companies like John Deere send staff to customers’ sites to learn, first-hand, how their products are being used and where better support can be provided. They return from these visits with customer-sensitized insight which is applied to many areas of process improvement.

Some sales types may view partnering as just another word for bonding, or establishing closer relationships with customers. It’s considerably more than that. In many customer–supplier relationships, the interactions can be somewhat adversarial, with one side winning or losing the bargaining war to get the best deal for themselves. Partnering requires rethinking this type of relationship, and focusing on mutual investment and the potential for mutual benefit, in other words, creating “win–win” situations.

Several years ago, the new vice president of AT&T’s NCS group saw significant declines in their business. NCS is the division that services all of AT&T’s computers and local area networks. This is not a captive service business, because the NCS customers have the right to go outside, self-maintain their equipment, or use NCS. NCS had been conducting customer satisfaction research, but the vice president discovered that almost one-third of the customers who reported being satisfied were potential defectors.

The vice president saw that he would have to go beyond understanding the customers’ needs and hoping that that level of insight would help create loyalty to NCS. Out of this recognition came a unique approach to customers, where they were encouraged to accept part of the responsibility for creating value and benefit for themselves while NCS accepted the remainder of the responsibility. Having created it, NCS then set about training its management and customer service staff to execute partnership arrangements and affiliations with customers. This new approach was a very different, unique, form of customer–supplier relationship for many of NCS’s customers, and it helped to strategically differentiate NCS.

After the first 6 months of applying partnership agreements to its customer relationships, the division’s revenues were up 20% and its profits were up 35%. Over the next 6 months, revenues increased to 26%, positive staff perception of dedication and customer focus increased to 85%, and new business soared by 600%.

Another excellent example of customer partnering by an American company is Intuit, Inc., creator of Quicken software for personal financial management, QuickBooks for business financial management, and TurboTax for tax computation. Several years ago, Scott Cook, Intuit’s founder, said:

Unwavering customer focus, that is exactly what we do at Intuit. We have well over 5 million customer contacts per year, whether on customer support phone calls or through our web site. Our research programs, beta tests, and usability labs put us in touch with thousands more every year to get their input and make our products better.

Intuit has set up “listening posts” around their company, wherever there is a customer interaction touchpoint—engineering, customer service, and technical support—to capture the voice of the customer. They use these contact points to learn about what customers want and then they apply the information to problem resolution and new product development. This may not seem innovative to some companies, but Intuit has raised partnering to a high art.

For Intuit, partnering doesn’t stop with customers. It extends to employees and strategic allies, as well. Their corporate culture is highly entrepreneurial, enabling staff to be creative and spontaneous, and highly mobile. They feel it’s important that senior managers be flexible and understand the entire business, so training and cross-functionalism are actively practiced. Scott Cook tells the story about suggestions for Quicken a prospective product manager made during the interview process. Two hours later, the prospect stopped back to visit the interviewer. He saw that his ideas were already being applied to a prototype on the computer screen. It’s an example of how Intuit listens to, and actively involves, its employees.

Intuit maintains partnership relations with financial institutions around the world: American Express, Chase Manhattan, Citibank, J. P. Morgan, Banque Nationale du Canada, Wells Fargo, E*Trade, Charles Schwab, Fidelity, and American Century, to name just a few. Intuit works with its business partners on a team basis, seeking solutions where its partners, customers, and Intuit all benefit. One example of this has been the Quicken Tax Freedom Project, which enables millions of lower income Americans to do online tax preparation and electronic filing with the Internal Revenue Service, a benefit to all parties involved.

Another partnership development has been to connect banking partners with their customers, giving bank customers the ability to conduct their banking and pay bills online using Intuit products. When this was originally written, Intuit had over one million customers using their products online; and they were working with 80% of the largest financial institutions in the United States of America, representing over 50% of our country’s checking accounts.

A company, in seeking to develop stronger partnership with its customers, should ask several questions:

• How do my customers perceive advantage, solution, and benefit—in other words, value—when selecting a supplier? What are the tangible and intangible elements of that value? These can include technical capability, customer service, prices, product/service variety, integrity and reputation, geographical location, delivery timeliness, product conformance and quality, and many other factors. Also, what are my strengths and weaknesses regarding processes, staff, structure, strategy, culture, and so forth?

• How do my customers do business with me? What are the dynamics of their supplier decision-making process? Do I understand how choices, such as share of dollar allocations, are made? What complaints, expressed and hidden, do my customers have about my company?

• What do I know about the competition—who they are, the benefits my customers perceive from them, their ability to partner with my customers more effectively than I can? How can I position my company, and communicate and provide benefit, in a non-copycat manner?

• What is unique and special about my company? What original positioning do I have, or can I create, that would make my best customers want to partner with me? What, if any, operational and relationship modifications do I have to make to achieve partnership?

Partnership is a beginning and basic strategy, and perhaps a new (but fundamental) strategic approach for many companies with their customers. Like any effective loyalty behavior program, it will work best if enacted for the long term.

Addressing Customer Complaints: Truth—or Consequences—of Using Social Media to Help Protect Brand Equity and Customer Loyalty (March 20, 2013)

A recent MarketingProfs article by Susan Marshall8 did a nice job of bringing to light the serious issue of expressed and unexpressed complaints. But, though building on the reality that more business-to-business (B2B) and business-to-consumer (B2C) customers are now using social media to voice their experience complaints, the article seems to suggest that the road to protecting brands and customer behavior lies largely in how responses to these online negative posts are addressed with the individual complainer.

The “complainer personas” (Figure 1.6) identified in the blog post are interesting, as are the suggestions for social response. However, the article, having identified the fact that few B2B and even fewer B2C customers will ever complain after a negative transaction or experience, misses the real world of online positive and negative informal content.

Figure 1.6. Complainer personas.

First, recent research indicates that the Huba and McConnell online “90–9–1” rule (90% lurkers, 9% commenters, 1% active bloggers) among those using online social media, identified several years ago, has now morphed into statistics more like 70%, 20%, and 10%. So, in actuality, online complaints are still being expressed by very few negative customers (though it is well understood that, though representing relatively low numbers, they can do a lot of reputation and purchase damage). Also, consistent with ongoing research by KellerFay, the vast majority of informal peer-to-peer communication continues to take place offline, that is, face-to-face and via mobile devices.

Bottom line

While there is definite value in identifying types of complainers and how best to respond to their issues, companies wishing to protect brand equity and customer loyalty behavior should make it a priority to gather a complete, and prioritized, inventory of negative customer issues.9 This will facilitate a strategic deployment of communication and resources to address, and mitigate, the individual and collective impact of complaints.

Are Corporate Customer Experience Intentions Overwhelmed by Senior Executive Risk Aversion and Other Roadblocks? Can That Be Changed? (February 13, 2013)

In developing plans and executing processes for optimizing customer experiences, and the parallel goal of increasing customer loyalty behavior, we often see the admonition “hope is not a strategy” at play within organizations. A recent Oracle study illustrates how wide the gulf is between corporate intention and corporate reality.

A key finding of this research, conducted among more than 1,300 global senior executives, was that over 90% of executives said that improving customer experience is a top priority over the next 2 years, in part because of the recognized risk to the customer base and to sales if they don’t; and a similar percentage said that their companies want to be customer experience leaders. However, just over one-third were only now beginning with formal customer experience initiatives, and only one-fifth considered their customer experience program advanced.

Another major disconnect was that, while four-fifths of the companies surveyed identified social media leverage as central to building stronger customer experiences, over one-third have no social or mobile approaches to support either sales or service. Reasons identified for not moving forward on these initiatives include inflexible technology, siloed organizational structures and systems, low investment, and inability to measure initiative results. This slow adoption, or non-adoption, seems to be not so much a reflection of stagnant international economy as it is of significant, historic corporate conservatism and risk aversion.

Customer experience and behavior studies have, for years, concluded that the vast majority (90% or more) of customers would switch suppliers because of poor customer service, and might even pay a premium for proactive service. In the Oracle study, fewer than half of all executives surveyed thought that customers would defect due to negative experiences (Figure 1.7), nor did they think that customers would pay for great experiences. That finding is yet another huge divide between “conventional wisdom” of executives and the realities of customer behavior.

Figure 1.7. Customers defect due to negative experiences.

In the Oracle study, it was found that company executives often believe that increasing spend on advanced technologies will help create more positive experiences for their customers; and many reported planning to do so. These investments, however, haven’t delivered the value that customers want, such as more personalized communication, omnichannel self-help, service and support through mobile and other channel devices, and integrating social media with service processes. This is further evidence of averting the real, but decidedly more effective, risks associated with improved customer experiences, namely,

1. moving to a more customer-centric, responsive, and participatory culture;

2. the removal of internal structural and functional barriers;

3. customer goals that are stated, restated, and restated again, consistently by senior executives across the enterprise; and

4. visible, real-world performance metrics, and reward and recognition for specific customer experience achievement.

There are lots of customer experience success models which can help to overcome risk aversion, and make worthy corporate intentions a reality. One particularly effective model is that articulated by Vernon Hill, the Chairman of Metro Bank in London, and the retail-oriented entrepreneurial executive who made Commerce Bank a regional marketing force in U.S. banking for several decades (Figure 1.8).

Figure 1.8. Metro Bank is a customer experience success model.

In his recent book, Fans! Not Customers (Profile Books, London, 2012), Hill stated:

We want our customers to be passionate about doing business with Metro Bank, to become Metro fans. Our philosophy is more than just a corporate mission statement: it’s a way of life. Our corporate spirit – something we’ve made a unique part of our social fabric – enables us to succeed. We are fanatically focused on delivering a unique customer experience. Over-investment in facilities, training and people, a focused geographic management, and countless mystery shops a year ensure that we always exceed our customer’s expectations.

As Hill observed:

You don’t have to be 100 percent better than the competition in order to beat them. You have to be 15 percent better, and you have to get better all the time. It’s all about standing out from the competition...

Customer Complaints: The Valuable Gift of Getting the Whole Picture+ (December 21, 2012)

Along with performance and loyalty metrics gathered through research, complaints are one of the best sources of customer data a supplier can have, yet most companies are getting half, or much less, of the complaint picture. Their portion of the enchilada is the complaints customers post via telephone, mail, fax, mobile, and Internet. Suppliers need to have the whole picture, available through good research and analysis.

Nothing can be as effective as complaints at either sinking a sales, marketing, customer loyalty, or service program or giving it new life. Complaints can be a positive or negative influence on customer’s word-of-mouth, as well as intention to remain loyal or to defect.

At a time when product and service loyalty continues to decline, consumer advocacy groups report that more than 50% of the buying public have problems or complaints with the products and services they purchase. Yet, it has been estimated that only about 2–10% of customers actually air their grievances to the supplier. Some industries experience notably high levels of customer complaint silence: financial services, food and beverages, pharmaceuticals, and high-tech. It’s been extremely well documented why their customers won’t complain:

• They’re busy, and they can’t or don’t want to take the time.

• They consider the complaint interaction a hassle and an annoyance.

• They see no direct value or benefit to them in making the complaint.

• They don’t think the supplier will do anything about the complaint.

• They can get what they want from an alternate supplier, so they switch.

Research by one company has found that over 40% of the companies in their B2B database who had a problem or complaint never informed the supplier about it. Their reasons for not expressing their complaints were remarkably similar to those given by consumers. We’ve seen other studies suggesting that, depending on the industry, unexpressed B2B complaints may range as high as 80%–90%, so this is hardly an exclusive B2C issue.

Even though the rate of expressed complaints is higher in the B2B world, the lost revenue potential of unexpressed complaints is significantly greater there because of the lifetime value of each customer.

In the 1990s, Banc One conducted a study of the loyalty-leveraging effect of expressed and unexpressed complaints on its retail business customers. The bank found that about half of these customers had service complaints. Of those with a complaint, only about half had actually expressed them to bank employees. In other words, fully one-quarter of the complaint picture was missing. Further, those who had not expressed their complaints were far less likely to continue their relationship with the bank than those who had registered a complaint and had it positively resolved.

When customers do complain—through customer service operations like the Campbell Soup Company’s Consumer Response and Information Center (which takes more than 300,000 calls a year), or the General Electric Answer Center, which is open all day, every day, or by other means such as e-mail, faxes, or letters, or outbound customer complaint solicitation—as noted above, how the complaints are received and acted upon makes all the difference in their effect on customer perceptions and behavior.

The potential for complaints to negatively impact customers’ future purchase intent and recommendation should never be overlooked. In loyalty research for a B2B client, a major manufacturer of paper and related products, it was determined that close to 40% of their high volume accounts had serious performance complaints. These complaining customers were 15% less likely to be positive about continuing to purchase from the client than those without a complaint. Other studies show similar negative loyalty effects of complaints.

Customers experiencing inefficient or insufficient resolution to complaints are not only less likely to repurchase or recommend from that supplier, they will spread their negativism—telling anywhere from 2 to 20 people about their experience in direct word-of-mouth, and significantly more via mobile devices and the Internet. And, as we’ve learned, the “long tail” represented by negative online postings means that consumers will see opinions of “badvocates” for a considerable period of time.

With numbers and results like these, it’s little wonder that, left poorly handled or totally unresolved, complaining customers can sabotage even the most carefully crafted marketing or customer loyalty program. The incidence of poor customer service demonstrated by many e-commerce Web sites has been actively reported in the media. Patrons will even set up their own Web sites so that other upset and former customers have a forum for their negative experiences.

So, having seen how complaints can hurt, how can complaints complement, and even enhance, a company’s customer loyalty, customer service, or CEM program? There are three ways:

• First, encourage customers to contact the company with questions, comments, problems, or complaints; and, make this as easy as possible.

• Second, identify the root causes of all complaints, registered and unregistered, so that their sources can be addressed and corrected.

• Third, enhance the effectiveness of problem and complaint resolution processes so that customers are provided sufficient contact venues.

There is a fourth method to consider when approaching complaint generation and management. And it may be the simplest, and most effective of all. Over the years, we’ve found that most companies, in their customer value/performance (transactional and relationship) research, fail to ask about complaints, either those that have been registered or those that haven’t.

We strongly advocate doing this. Complaints, after all, are a different category of involvement with a supplier than just low performance ratings. They’re stronger. They’re certainly more consequential. If we can identify those complaints that have been registered and how they have/haven’t been resolved, and those complaints that haven’t been registered (and the reasons for non-registration), this represents a complete inventory and landscape of customer complaints. It sheds new light on the complaint process. Their specific potential effect on customer loyalty can then be modeled for prioritized action.

The lesson here, as has been proven again and again, is that when customers are encouraged to dialogue with suppliers if there are performance delivery problems or concerns, that opportunity for enhanced value provision actually creates stronger, more bonded and productive relationships between them.

Having a comprehensive database of the registered and unregistered complaints gives a supplier the entire spectrum of customer negativity, enabling corrective action to be much more focused and relevant. When this is combined with customer profile and contact data, and assessments of key elements of performance delivery, and metrics about intended behavior (advocacy level, brand bonding, likelihood of future purchase, likelihood to recommend, and so forth) through targeted loyalty and winback research, companies can be far more effective in optimizing customer loyalty behavior. That’s the clarity represented by the whole picture.

As Janelle Barlow famously wrote almost 20 years ago, a complaint is a gift. So, an unregistered complaint is an unopened gift. Is it a gold watch or a holiday fruitcake?

Milton Waddams: Valuable Lessons from the World’s Most Alienated Employee and Customer (December 18, 2012)

Does anybody (besides me) remember Milton Waddams (see Figure 1.9), the disgruntled, slightly off-kilter employee from the amusing, now almost cult-like, 1999 movie, Office Space, Milton’s role was pivotal to the final outcome of the plot; and he represents, admittedly in an over-the-top way played for entertainment, what can potentially go wrong with disaffected, ignored employees, and also angry, ignored customers.

Figure 1.9. Milton Waddams in the movie Office Space.

For example, as the movie plot unfolded, Bill Lumburgh, an uptight company vice president who was the office’s senior executive, made Milton’s working life a growing nightmare. As Milton’s distress over his increasingly bad treatment grew, Bill said: “Milt, we’re gonna need to go ahead and move you downstairs into storage B. We have some new people coming in, and we need all the space we can get. So if you could just go ahead and pack up your stuff and move it down there, that would be terrific, OK?” Milton’s response: “Excuse me, I believe you have my stapler...”

Later, Milton, seemingly talking on the phone, said to no one in particular, “And I said, I don’t care if they lay me off either, because I told, I told Bill that if they move my desk one more time, then, then I’m, I’m quitting, I’m going to quit. And, and I told Don too, because they’ve moved my desk four times already this year, and I used to be over by the window, and I could see the squirrels, and they were married, but then, they switched from the Swingline to the Boston stapler, but I kept my Swingline stapler because it didn’t bind up as much, and I kept the staples for the Swingline stapler and it’s not okay because if they take my stapler then I’ll set the building on fire...”

Near the film’s finale, the alienated Milton carried out his threat and set the building on fire. First, however, Milton reclaimed his Swingline stapler from Bill’s office; and, at the same time, he also stole some money left for the boss by another employee, Peter Gibbons, the movie’s hero (who’d earlier embezzled it, but, suffering from remorse, returned it). At the end of Office Space, Milton becomes the quintessential picky customer, while using the money he pilfered for vacationing at a Mexican beach resort. The last lines of the movie go like this, as Milton speaks to a waiter about his botched drink order:

Milton Waddams: |

“Excuse me? Excuse me, senor? May I speak to you please? I asked for a mai tai, and they brought me a pina colada, and I said no salt, NO salt for the margarita, but it had salt on it, big grains of salt, floating in the glass...” |

Mexican Waiter: |

“Lo siento mucho, senor,” i.e. “I’m very sorry, sir.” and [under his breath] “Pinche gringo,” i.e. “Old, stupid, worthless, f______ American” |

Milton Waddams: |

[as the waiter walks away] “And yes, I won’t be leaving a tip, ’cause I could...I could shut this whole resort down. Sir? I’ll take my traveler’s checks to a competing resort. I could write a letter to your board of tourism and I could have this place condemned. I could put...I could put...strychnine in the guacamole. There was salt on the glass, BIG grains of salt.” |

The customer-centricity lessons: Listen, and pay attention, to employees. Listen, and pay attention, to customers, even the Miltons of the world.

Section Summary and Perspective

Many companies are actively product-centric. They believe that strategic advantage is based on the product and the expertise behind the product. The organizational structure (divisions, groups, and teams) is set up around products and projects, employees are rewarded based on their ability to sell existing products or create new products, and brand equity is seen as having greater value than the customer. In these companies, all customers are often treated the same, irrespective of current or potential value to the enterprise. There are, however, cracks in this concept, due principally to globalization, speed of new technologies, deregulation, and the rising power of consumers (to get what they want, when they want it, and from whomever they select to provide it). Product centricity can put these organizations at risk relative to companies that are customer-centric.

Customer centricity is a strategy to fundamentally align a company’s products and services with the wants and needs of its best customers and those which can readily be bootstrapped (through research segmentation tools such as advocacy level) to become more financially attractive. It is about identifying the most valuable customers and then doing everything possible to bring their (positive and negative) ideas into the center of the enterprise, create value for them, generate revenue from them, and to find more customers like them. That strategy has a specific business outcome goal: more profits for the long term. This objective is one that every enterprise would like to achieve; and, it can be attained if an organization is willing to move past outdated ideas about customer–company relations and rethink organizational culture, processes, and value.

It will require installation and support of a function such as the CCO, the embracing of customers as partners and collaborators, the movement from such conventional employee concepts as engagement, to ambassadorship, and the active acceptance of the need for customer proaction.