Management Overview

In endeavoring to understand drivers behind the behavior of customers, and predict future behavior, we have moved a great deal in the past 30 years. Beginning with perceptions of rational (and emotional, or relationship, quality), we have moved through satisfaction, retention, loyalty, and more simple, and more sophisticated, analytical approaches. We have now entered a period where the emotional elements of value dominate brand decision making, and understanding the underpinnings of strong behavior and brand bonding is paramount to leveraging, and monetizing, customer insights.

Attitudinal Segmentation Can Be Both Misleading and Potentially Dangerous

Attitudinal research frameworks (sometimes identified as “models”) have been used for decades to help segment customers according to level of attachment to a brand, and potential for response to marketing initiatives and potential for future purchase. However, because they are built on tactical and passive levels of engagement, rather than proven behaviors, they can be superficial, and even misleading, predictors of behavior and response. Similar observations (confirmed by detailed customer research) can be made regarding quasi-behavioral measures, such as single question metrics and loyalty indices. Availability of stronger frameworks, built around customer bonding and brand passion, will provide greater strategic, and predictive, accuracy and reliability.

Getting Serious About Performance Metrics

As the market research industry witnesses a decrease in ad hoc studies, there is increased pressure for actionability. Performance scoring techniques, such as Net Promoter Score (NPS) and Customer Effort Score (CES), while having some value as a decision guide, have serious limitations in terms of granular application. Though positive service differentiators can have an effect on downstream customer behavior, merely reducing effort in receiving the service has questionable impact on value.

Real-World Customer Experience Research

Some practitioners have expressed concern with the objectives, and applications, of quantitative customer research. While some research may fall short, well-designed customer experience studies address both the emotional and the functional drivers of perceived value and behavior. Further, they reflect the contemporary power of informal communication, and examine both the total experience and its value components. Finally, analyses from real-world customer research do not equate correlation with causation, and facilitate behavioral predictive modeling.

A Look into Brand and Customer Research of the Future

The new dynamics of customer decision making are having a profound effect on customer, advertising and communication, and brand positioning research. Research must now focus not only on fully understanding the impact of trust and relationship, but also the proliferation of online and offline information sources. It also places more emphasis on the amount and quality of data which are generated, plus the way such information is analyzed and integrated. Finally, these changes place similar emphasis on researchers as strategic consultants in the conjoined arena of syndicated and ad hoc customer experience, and brand and communication impact studies.

Customer Loyalty Matters—But Is Often Not Enough

For years, marketers have been endeavoring to create high customer loyalty, measuring it, protecting it, and rewarding customers for exhibiting it. Social word-of-mouth, online and offline, has changed the landscape for understanding customer behavior and designing brand positioning. Brand relationships and customer advocacy are now the ultimate attainment of behavior; so, while customer loyalty focuses on retention, cross-selling and upselling, that is, creating macro “barriers to exit,” today it is customer bonding which has become the highest expression of experience-based customer loyalty behavior.

Customer Loyalty Behavior Modeling—What Works and What Doesn’t

Organizations actively model many marketing-related activities, such as customer lifetime value, innovation, business planning—and customer behavior. Until the recent past, these models focused on product quality, satisfaction, or engagement. There are now a number of market research models, or frameworks, which purport to identify drivers of customer behavior and brand selection. In virtually all cases, these models incorporate fairly traditional measures such as satisfaction and loyalty; however, customer bonding models are more contemporary and accurate.

Why Segmentation by Consumer (and Employee) Attitudes Is Yesterday’s News—and Potentially Dangerous for Organizations (October 2, 2013)

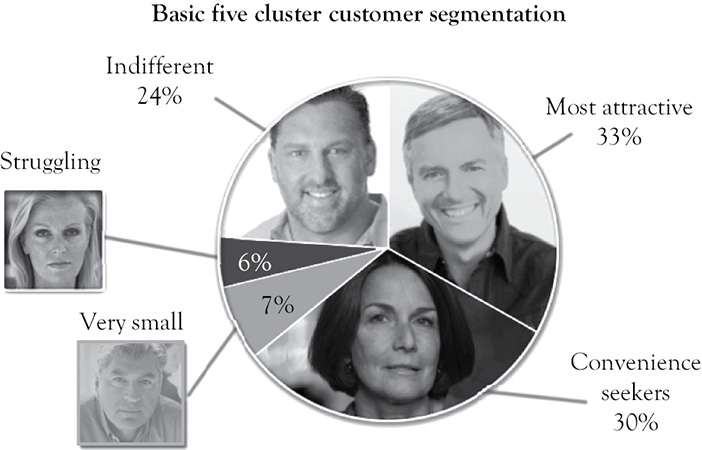

For years, B2B and B2C marketers have relied on attitudinal segmentation research to help them group their current customer base, and potential customers as well, for communication, promotion, marketing, and experience initiatives. The thesis has been that, by asking a small, but meaningful, set of attitudinal questions, they would be able to develop an index, algorithm, or framework equation that ranked these consumers by propensity to buy, both near term and long term.

These frameworks—they’re arithmetic, so we can’t rightly call them models—typically include questions regarding the importance of elements like value for money, acting with the consumer’s interests in mind, credit and payment terms, having knowledgeable employees, offering products which will meet the consumer’s needs, and the like. From these questions, basic segment categorization can be determined; and, once these three, four, or five segments are established, we’ve often seen marketers go on to build assumptive plans, and conduct further, more detailed, research around them.

The goal of these approaches is to produce attitudinal segments which the questions can predict with high accuracy, often in the 80% or 90% range. This creates what economists would call a “post hoc ergo propter hoc” situation, Latin for “after this, therefore because of this.” It is a classical logic fallacy, essentially saying that A occurred (the responses to the attitudinal questions), and then B occurred (the cuts, or segments, of consumers). Thus, the fallacy concludes, A caused B. So, for our example, once the B, or segment creation, stage has been established, further fallacies, such as creating reliable marketing, operational, and experiential strategies around these supposed propensities, can be built. It’s a classic situation, where correlation is thought to be the same as causation. As your economics or statistics professors should have told you, correlation and causation are far from being identical concepts.

As a consultant and analyst, I’ve seen the unfortunate result of this application of research and analytics play out on a first hand basis on multiple occasions. Here’s a recent one, reflective of negative outcomes which can occur. A client in the retail office products market had been using an attitudinally derived element importance question framework for small business market segmentation purposes. The attitudinal segment assumptions went unquestioned until follow-up qualitative research was conducted to better shape and target their planned marketing and operational initiatives. Importance of certain products and reliable service was identified in the research as key areas of focus and opportunity for the office products retailer; but, in the qualitative research, power of both focus areas appeared, anecdotally, to be consistent across all segments. And, even though implied supplier roles were suggested to build purchases, this was much more “leap of faith” based on the established quantitative research segment personas than actual qualitative research findings.

Figure 3.1. Customer segmentation example.

There are related issues with what we can describe as quasi-behavioral measures, such as single question metrics (likelihood to recommend to a friend or colleague or the amount of service effort required on the part of a consumer), or traditional customer loyalty indices (where not only future purchase intent is included, but also attitudinal questions such as overall satisfaction). It’s not that they don’t offer some segmentation guidance. They do—on a macro or global level; but they tend to be less effective on a granular level, especially where elements of customer touchpoint experience are involved.1,2

And, they tend to have limitations as predictors of segment behavior, a key business outcome for marketers and operations management. When compared to research and analysis techniques such as customer–brand bonding, which is a contemporary, real-world framework built on actual customer experience, high satisfaction scores, high index scores, and high net recommendation scores produced likely future purchase results (in studies across multiple industries) which were often 50%–75% lower than brand-bonding frameworks.

So, that’s the scenario. The challenge, and potential danger, for marketers and those responsible for optimizing customer experience is that these attitudinal and quasi-behavioral questions are just that—attitudes and quasi-behaviors. Attitudes are fairly superficial feelings, and tend to be both tactical and reactive. And, because they are so transitory, their predictive value is often unstable and unreliable. Quasi-behaviors are also open to many similar challenges. More importantly, attitudes and quasi-behaviors are not behaviors, such as high probability downstream purchase intent based on actual previous purchase, evidence of positive and negative word-of-mouth about a brand based on prior personal experience, and brand favorability level based on experience. These are especially valuable in understanding competitive set, and they have real, and very stable, predictive and analytical value for marketers.

As Jaggers, the lawyer, said to Pip in Charles Dickens’ Great Expectations, “take nothing on its looks; take everything on evidence. There’s no better rule.” For marketers, that’s excellent shorthand for taking everything on behavior, and perceptions based on documented personal experience, rather than attitudes and quasi-behaviors.

It’s Time to Get (Really) Serious About Performance Metrics: What (Really) Works and What (Really) Has Actionability Challenges... + (June 18, 2013)

The recently published 2013 Honomichl Top 50 Report, chronicling business performance of major, U.S.-based marketing/advertising/public opinion research firms, shows an overall decline. Taking out the effect of reduced government spending on market research, and a sluggish economy, there has been a major investment pullback in ad hoc survey studies, as clients experience increasing pressure on their marketing and communication budgets.

This is not yet a doomsday situation, but it does bring front-and-center the requirement that companies, and especially researchers and marketing planners, should be getting much more serious about having, and leveraging, actionable performance metrics. These metrics need to both reflect (i.e., show causation rather than just correlate with) and help build the most monetizing customer marketplace behavior. Two of the more recent, and actively adopted, approaches for doing this—NPS and CES—each carry some significant interpretation and actionability challenges; and there has been much useful (and sometimes heated) back-and-forth among practitioners about the relative merits of various customer experience and marketing metrics and models now being applied, and how granular their results can, or can’t, be.

Jim Tincher recently posted a CustomerThink blog on CES. Thoughtfully, what he has done to build interpretation value into the effort question is to add a follow-on question addressing effort expectations, a surrogate for degree of importance. This offers some dimensionality to the issue of effort. Here’s how I responded to Jim’s blog, also providing a link to perspectives on NPS: As an overall response to your blog, I’m not a strong supporter of CES, for the reasons I’ll enumerate; however, that said, your add-on expectations question provides a critical measure for assessing the level of importance attached to the level of effort. You and I also agree on challenges associated with endeavoring to use NPS for anything more granular than aggregated performance interpretation.

CES, for those who may be unfamiliar with the term and concept, was originally introduced in mid-2009 by the Customer Contact Council (CCC) of the Corporate Executive Board, in a presentation titled “Shifting The Loyalty Curve: Mitigating Disloyalty by Reducing Effort.” A client asked me to review it at the time (when I was a Senior Vice President and Senior Consultant in Stakeholder Relationship Management at Harris Interactive); and, among my three pages of comment were

There is no holistic view of customer experience in CCC’s conclusions represented in the CES or effort reduction/mitigation focus. With specific respect to the multiple CES methodological challenges, we (Harris senior methodologists and I) feel that a customer effort score is too one dimensional to capture the overall customer experience or, more narrowly, the customer service experience. Again, customer experience means looking at the overall perception of value through use or contact. It involves the entire system. CCC, for instance, is using callback tracking as a “standard proxy for customer-exerted effort’; and very much like NPS, building their case on a single question (“How much effort did you personally have to put forth to handle your request?,” on p. 71 of the presentation), and then taking it to the next level by having a CES Starter Kit (p. 73). Our approach is to validate the impact of customer service within the overall experience and, as well, more around actual behavior than anticipated behavior.

If we’ve learned anything from the Kano Model since the 1980s and early 1990s, it’s a recognition that dissatisfiers can hurt loyalty behavior and enhancers can help drive more positive downstream customer action. Those receiving customer service will not be particularly energized by having their problem solved or questions answered, because these are table stakes and basic expectations resulting from contact. Positive service differentiators, though, can have a beneficial impact on customer experience and brand perception, informal peer-to-peer communication (offline and online word-of-mouth), share of wallet, etc.

To paraphrase some of Bob Thompson’s thoughts on CES, the measure principally gets at how well customers are placated and mollified, not the degree to which proactive, or value-added, benefits provided have leveraged their behavior, especially delight. Extensive measurement of neutral, reactive customer value delivery shows little effect on loyalty or advocacy. Expectations, from the vantage of customers, must be exceeded—and in ways that add to perceived value.

Largely irrespective of how much customers’ touchpoint effort level is mitigated, without meaningful value overdelivery there is little opportunity to have a positive impact on loyalty. Becoming (really) serious about leveraging performance metrics means that users must get past the marketing hype and puff represented by some measures and models and focus only on what reliably helps move the customer behavior needle.

What’s Positive, Real-World, and Actionable In Customer Experience and Brand Research (March 21, 2013)

This is a statement, and not a question. It is a partial response to Steven Walden’s blog about what’s wrong with quantitative marketing research.3

My perspective is that there are some truths in the content he presents, but there are also differing points of view on what works and what doesn’t. Namely, the bottom-line objective of most research, especially brand equity and customer experience research, should be to help optimize (through actionability) an enterprise’s, product’s, or service’s strategically differentiated value proposition. And, in reviewing many B2C and B2B customer experience questionnaires and reports over the years, some researchers and some studies, to their detriment, miss the forest for the trees; and there can also be a tendency to miss the story line and “boil the ocean.” Most quantitative customer experience research, however, contributes effectively to enterprise marketing resource allocation.

To a degree representing my many research colleagues around the world, I offer several examples of what those of us responsible for well-designed, contemporary quantitative customer experience studies get right:

1. We understand that consumer decision making is not, and has never been, linear; and, for both B2B and B2C, has always been about both the functional and emotional.

2. We understand that such metrics as are applied must reflect the real world of informal communication and influence.

3. We understand that to equate causation with correlation is folly.4

4. We understand that total experience is key to value perception and loyalty behavior, but there are also significant, leveraging, components of the experience.5

In my response, it was also noted that there is little doubt that the world of qualitative and quantitative market, brand positioning and messaging, and customer experience research has been changing. It was Pasteur who said “Chance favors the prepared mind,” and prepared researchers will have less chance to be caught off-guard by the array of challenges Walden cited.6

We end with what should be regarded as a key point in his piece: Most customer experience research models, indeed most research studies, tend to back-cast rather than help forecast behavior (through simulation), but models based on how decisions are really made can generate research results and insights that are considerably more predictive, more relevant, and more monetizing.

Gathering and Leveraging Customer Decision Insights: A Look into the Brand Impact, Communication, and CX Research Future (December 10, 2012)

There are strong currents of change in the worlds of customer, advertising and communication, and brand positioning and behavior impact research. These new dynamics of customer decision making will impact the levels of innovation, insight, and action for everyone applying any form of syndicated or custom research for making experience, brand equity, advertising, and communication plans. We’re not just speaking of the tools for collection—such as the declining use of telephone surveys, except for some targets and regions, in favor of online and other methods. Sea changes are taking place in research.

In studies among research practitioners, on both the corporate and vendor sides of the desk, there is strong belief that innovative and creative methodological advances—such as fully understanding the level of trust and relationship value that customers want with brands and suppliers—must move to reflect the explosion of online and offline data sources. As well, practitioners understand the need to integrate all of this information, produce more actionable insights, and drive better business decision making and more positive outcomes.

Perhaps the biggest challenge can be boiled down to one word and concept: DATA. Simply stated, the sheer volume of information which can be generated through online informal brand-related content, as well as customer profile data (from public and corporate databases), and syndicated and custom research must be effectively integrated. Further, there must be requisite methodological and analytic capability exhibited by professionals, and the systems they utilize, to take these integrated data and generate actionable, meaningful insights. In the face of this complexity, customer, advertising, and brand marketing researchers must become consultative and strategic professionals to keep from becoming commoditized and marginalized.

From my perspective, this is a significant opportunity for the marketing research community rather than a threat. Studies have found that some elements of research—brand strategy, customer and shopper behavior, advertising and promotional effectiveness, cultural/multicultural monitoring, media mix planning, and so forth—will endure over time.

Figure 3.2. Many ways to think about customer behavior.

Text analytics (sentiment/semantic analysis), and data generated through digital and mobile marketing, are emerging trends receiving research attention, and new methods must align with what is evolving here. The same is true of touchpoint effectiveness (modes of consumer contact, such as advertising, customer service, PR, promotion through sponsorship, and so forth), social networking, and even the potential of neuroscience, which are all becoming more important and receiving more attention as emerging marketing elements.

For researchers to become strategic consultants in this arena, the name of the game will be adaptation to the growing complexity of marketing in a digital world and the explosion of data streams from it. Another key trend, leveraged by marketing, communication, brand and research budget shrinkage, and corporate desire for more integrated insights, is the movement seen in an increasing number of companies: the blending of these functions into a single, overarching discipline, which also drives customer-centric corporate culture. Innovation, whether in syndicated or custom research, or in the application of customer, brand, and communication impact data, will help make this happen.

Why Customer Loyalty Matters (and It Absolutely Does!), But Is Often Not Enough+ (September 19, 2012)

Businesses, hoping to capitalize on the explosive, potential power of word-of-mouth in their marketing programs, have come to something of an epiphany. The seemingly simple process of people talking to one another about a product or service, a behavior that has been around for as long as humans have lived in civilized communities, is not as easy to manage as they once believed nor, in most cases, has it generated the lofty and consistent results they had expected.

Over the past decade, the concept, and effective execution, of offline and online social (and business-related) word-of-mouth has become extremely important to marketers as, increasingly, B2C and B2B customers have shown distrust, disinterest, and disdain for most supplier messages conveyed through traditional media. This has also caused companies to reconsider the role of brand in driving relationships.

Several books have served to raise awareness of such new-age social word-of-mouth marketing components as influencer relations, buzz, viral communication, neural networks, online community, collaboration, consumer-generated media (blogs, boards, user forums, online reviews, and direct supplier feedback), and other peer-to-peer dialogue. However, given the availability of techniques such as text mining, analytics, electronic (consumer-generated) content monitoring and harvesting, and downstream behavior analysis, they have barely scratched the surface in defining how to use these techniques, and assess their effectiveness, to achieve and sustain success.

Today, we are witnessing customer-driven marketing through empowerment and self-management; and companies have often found themselves in the backseat of the new customer–supplier relationships. They are forced to modify existing communication techniques, create new ones, or do both, so that they can be positioned to generate brand advocates (and avoid or minimize indifference and sabotage) among their customer bases. How they use, or misuse, these new-age relationships and techniques, how they leverage brand passion and engagement, and how they assess the return-on-customer effectiveness, and level of monetization, of their initiatives will change how social word-of-mouth is pursued by both small and large enterprises.

The false sense of simplicity surrounding the early application of social word-of-mouth techniques has given way to real challenges that businesses must address:

What is true word-of-mouth versus artificial word-of-mouth, and why is it essential for marketers to distinguish between the real and engineered version?

How do marketers actually build plans and position their brands around social word-of-mouth, run an effective word-of-mouth program, and track its success?

Is social word-of-mouth the same in every market or geographic situation; and, if not, what are the key differences for marketers to understand?

Why is brand relationship, composed of brand passion and customer advocacy, the ultimate attainment of behavior on behalf of a brand or supplier; and, what is customer sabotage and how can it be avoided?

What kinds of research and metrics are available to monitor the revenue impact of social word-of-mouth and conjoined brand passion and advocacy behavior among customers?

How does word-of-mouth compare to recommendation as a downstream behavior lever; and why is the act of recommendation both considerably more complex and less leveraging of customer behavior than originally believed?

What is necessary to get staff buy-in, and what is the role and effect of employee advocacy and sabotage in word-of-mouth?

What is the real, likely future of social word-of-mouth marketing?

For many years, marketing practitioners have been focused on creating high customer loyalty. How do you measure it, how do you protect it, and how do you reward customers for their loyal behavior?

What we are coming to understand now is that creating a loyal customer may not be enough to prevent risk and even loss. Customers may say that they are loyal to the brand and say that they will use the brand again; but, given the opportunity, they will often switch with little or no hesitation. We have seen this in industries such as retail, wireless telecom, credit cards, and travel, each of which has spent more than almost any other industry on loyalty tools; however, the switching virus has spread to many other B2B and B2C sectors to the point where it is at pandemic levels.

At the same time, we are seeing a group of brands such as Google, Red Bull, Zappos, Apple, Umpqua Bank, Wegman’s Markets, Amazon, IKEA, and Harley-Davidson, each having a dedicated and enthusiastic group of customers who are more than just loyal—they are bonded to the brand. Once these select companies have built a critical mass of customers who have bonding behavior, they enjoy benefits which most brands could only dream of. They get massive social word-of-mouth exposure, they have lower customer acquisition costs and marketing budgets, have lower customer service (CS) costs (or none in the case of Google), they can enter new market areas, and so forth. The most remarkable example of brand bonding may be Google, which not only doesn’t do any marketing (in the traditional sense) but also doesn’t have any customer service; and, yet, Google still has a large cadre of users who are passionate about their value proposition and have a powerful brand relationship.

Bonding, the highest expression of customer loyalty behavior based on experience, will be the standard for successful brand and corporate performance going forward. And brand relationships, the intersection of brand passion and positive customer behavior, have the potential to be even more connected to significant business outcomes.

Business and academic thought leaders have discovered the powerful leverage and impact on marketplace behavior of customer bonding and brand relationships. Major consulting organizations have led the way regarding application and business outcome of bonding. In this time of the requirement for extreme marketing budget accountability, groundbreaking research and analysis has been conducted, in multiple business sectors, which absolutely makes the monetizing outcome case for customer bonding, brand passion, and the linkage which exists between them.

Customer Loyalty Behavior Modeling: What Works in the Real World, What Doesn’t, and Why (August 8, 2012)

It seems that there’s a model, or a framework, for just about everything in business these days. Organizations and management have been guided by evolving models for over 100 years. They are used for corporate architecture, overall business planning, decision-making guidance (such as strength/weakness/opportunity/threat [SWOT]) analysis), customer lifetime value, innovation, and financial resource allocation.

There have been models for understanding, or endeavoring to understand, human behavior, dating back to Freud, Jung, and, classically, Abraham Maslow (Hierarchy of Needs) and Herbert Simon (Utility Theory).

Formal research on customer opinions has been going on since the 1950s. Much of it had to do with perceptions of product/service quality and satisfaction, engagement, and eventually loyalty and recommendation. For decades, data on these attitudes and feelings was sufficient to provide companies with general insight and direction, and models of customer behavior reflected the focus on perceived emotional and rational elements of value. Customer research has seen its share of models over the past 20 years or so. Without naming names, some of the more prominent ones include the following:

• Model C—an 11-element model which identifies strength of customer relationship with a brand or company based on levels of engagement. In this model, customers can be considered to be in states ranging from full engagement to active disengagement.

• Model I—a model containing questions which identify components of attitudinal loyalty, behavioral loyalty, and customer value

• Model N—a “one number,” or single question, metric which hypothesizes that revenue growth can be achieved by understanding, on an aggregated basis, the level of recommendation customers give to a brand, product, or company

• Model M—a complex model which contains loyalty “ingredients,” such as marketplace factors (availability, price, and so forth), individual customer differences (risk aversion, variety-seeking, and so forth), experience attributes (sales channel, service), and measures of intention and past behavior

• Model W—a model based on 1994 academic research which identifies attachment driven by the degree of customer conviction about the product or service, and perceived product or service differentiation. The model segments customers based on multiple states of attachment and purchase.

• Model S—a model which considers customer behavior from the perspective of the competition in the marketplace, based on opportunities and barriers that the competitors present to customers

By the early 1990s, control of brand and supplier selection had shifted away from companies and moved to consumers, a result of several pivotal, converging factors:

1. Growing Internet penetration and mobile device usage, as communications enablers.

2. Oversaturation of “push” advertising and promotional messaging through traditional mass electronic and print media.

3. Heightened public distrust in the honesty and authenticity of corporations, in both B2B and B2C business sectors.

This was a major, seismic change in the way businesses regarded customers, and the nature of information needed from them. Significantly, none of the models cited above took these changes into consideration. Instead, they continued to view the customer through a lens where the company controlled, or at least managed, customer decision making rather than the other way around. These models did not incorporate the customers’ ownership of company and brand selection, or what elements contributed to both choice and loyalty behavior.

Beginning around 2000, major consulting organizations began to recognize that these critical changes were likely to have a profound impact on businesses. Instead of relying solely on such historic measures as satisfaction, loyalty, engagement, and recommendation, companies would need to identify and focus on something more contemporary, more actionable, and more predictive of key monetizing business outcomes, such as share of wallet. That “something” was ultimately defined as customer bonding, that is, behavior driven by a strong relationship and bond with the preferred brand and active, voluntary online and offline word-of-mouth on behalf of that brand.

The consulting companies conducted many insightful bonding studies, issuing statements such as the following:

Advocacy is a deeply-rooted, emotional connection which relies on trusted, effective non-traditional communication and engagement channels.

Word-of-mouth is the primary factor behind 20 to 50% of all purchasing decisions. And its influence will probably grow.

Leading companies want to build strong bases of loyal profitable customers who are also advocates for the organization. Advocates spend more, remain customers longer, and refer family and friends, thus increasing the quality of the existing customer base and new acquisitions.

We predict that customer advocacy will be the new focus for business leaders. Customer advocacy will become the single most important initiative that cutting-edge, forward thinking companies will adopt.

Having identified the power of customer bonding to influence the customer’s own behavior and the behavior of others, the next challenge was to create, and prove the effectiveness of, a state-of-the-art research metric, or framework, for measuring and leveraging it.

So, customer bonding, as identified by these consulting companies, could now provide organizations with many valuable business outcome benefits. This new consumer influence also meant that market research companies would need to evolve beyond historic methods of interpreting customer attitudes, and determining how those attitudes could impact behavior, to incorporate drivers of customer bonding. Some new models were created, principally to evaluate emotional connection; however, in general, the risk-averse market research industry has been slow to awaken to the new realities of customer decision making represented by customer bonding. Or, they have applied more benign behavioral definitions, such as “customer engagement.”

Bonding, principally based on customer word-of-mouth and impression of the brand or vendor, has tremendous power and potential to create desired high-end customer behavior. Word-of-mouth, however, is a double-edged sword; and customers’ negative communication, as much as praise, can have a damaging effect on other customers and non-customers, as well as the communicating customer himself or herself.

Bonding segmentation research and analysis offers a number of value-added benefits:

1. Based on actual past behavior, it is perhaps the most reliable barometer and predictor of customer behavior available.

2. The ability to blend attitudes with positive and negative word-of-mouth and emotional brand connection, creating customer groups whose behavior has direct linkage to business outcomes.

3. Enables action prioritization of image, performance, and messaging factors to optimize advocacy and loyalty, and to minimize alienation.

4. Application to any customer segment (demographic, dollar value, product, usage frequency, and so forth) in virtually any industry, and any value or experience delivery component (such as customer service). Can be applied to transactional, brand and communication, and strategic relationship studies, offering both independent topic and conjoined research.

5. Identifies strength of brand franchise in the marketplace, especially in monetizing factors, relative to competitors.

As concluded in a Peppers and Rogers 2011 white paper (Cultivating Customer Advocates: More Than Satisfaction and Loyalty): The benefits of building advocacy can’t be ignored. Satisfaction and loyalty are important, but they’re old news. It’s a new dawn in customer experience strategy, where the customer controls over 50 percent of the brand message. Forward thinking companies will be the ones that identify and work with their customer advocates to genuinely build trust in the brand, the customer base, and the bottom line.

Section Summary and Perspective

Few elements of customer experience and behavior management have received so much scrutiny, or created more controversy, than performance measurement and metrics. Fairly recent models, and metrics like NPS and CES, have entered the research market positioned as contributors to, or surrogates for, level of brand and value performance, each having significant challenges in terms of granular actionability. Further, these don’t adequately represent the presence or power of informal offline and online content in the lives, and decision making, of consumers.

Behavior measurement must, as well, take into account the impact of emotions and relationships on brand favorability and customer loyalty. And, it must also move beyond traditional approaches to research which focus on attitudes, and then infer downstream marketplace action based on these tactical and superficial opinions.

Finally, the end goal of performance research must move beyond satisfaction, retention, loyalty, engagement, and recommendation. To do so means accepting customer–brand bonding as representative of the new dynamics of consumer behavior.