1

E&I Education: An Overview1

This chapter defines the nature of entrepreneurship and innovation, as well as the limits and possibilities for teaching and learning the skills involved. It discusses some of the differences between traditional management education and training versus E&I-focused programs. It briefly argues the eternal question of whether entrepreneurship can be taught. It presents a framework for understanding the E&I education landscape and some of the processes and expected outputs of this educational system. It illustrates this approach with a case of a French University E&I education program. Finally, it presents the Collaborative Interactivity approach to teaching and learning E&I.

This section is designed to help professors to better understand some of the challenges of E&I teaching. It is highly theoretical and should be of little interest to students. If you are a student, we suggest you skip this section entirely and go straight to Chapter 2, about how to develop your entrepreneurship vision.

1.1. Defining entrepreneurship and innovation

The phenomenon of entrepreneurship lacks a single, universally accepted definition (Valerio et al. 2014). Kirzner (1999) defines it as a process of identifying and exploring (frequently unnoticed) profit opportunities. Klapper et al. (2010) describe it simply as the process of creating new wealth. In its narrowest definition, entrepreneurship is the process of converting ideas into products or services and then creating a new venture to market it (Johnson 2001). Innovation, on the other hand, can be simply defined as “the process of turning opportunity into new ideas and of putting these into widely used practice” (Tidd and Bessant 2013, p. 19). As can be seen from the definitions above, E&I are intrinsically correlated. Creating new ventures does not necessarily imply innovating and, conversely, one may be an innovator without creating a new business. Nevertheless, it can be argued that the kind of entrepreneurship that creates most value does involve innovation. As Peter Drucker (1994) suggested, innovation is the main tool of entrepreneurs.

Joseph Schumpeter’s view of this phenomenon is widely accepted as one of the most relevant and comprehensive to date. According to this Austrian economist who pioneered the field, an entrepreneur is someone involved in the creation of innovative and growth-pursuing firms (Schumpeter 1982). He argues that innovative companies grow faster by introducing new goods or new methods of production, by opening new markets, by conquering of new sources of supply and by carrying out a new organization of an industry. These categories are the basis for the standardized types of innovation as defined by the Oslo Manual for Collecting and Interpreting Innovation Data (OECD 2005): product innovation, process innovation, marketing innovation and organizational innovation.

Let us examine each of the Schumpeterian categories below.

- – New products or services. Arguably the most visible part of innovation, this process consists of identifying unmet customer needs and developing solutions that deliver superior value. Superior value can be achieved by designing products and services that offer better quality, more convenience, lower cost or any other differentiation attribute that is valued by the target customer. An example of this kind of innovation would be a more effective toothpaste, a less expensive computer or a better designed customer experience.

- – New methods of production. Also known as process innovation, this approach consists of improving existing methods to lower costs, increase efficiency, lower environmental impact or achieve any other enhancement in the way products and services are created and delivered. Examples of this type of innovation could include improving the quality, reducing the cost or increasing the speed of a project, or reducing the amount of wood used in the manufacturing of furniture.

- – Opening new markets, foreign or domestic. Contrary to widespread belief, an innovation does not have to be “new”. If an existing product, service or process is introduced in a new market segment which was previously unfamiliar with its benefits, this can be considered an innovation in the Schumpeterian perspective. Examples include successfully introducing a gaming console targeting non-gamers or introducing an old product in new country or region.

- – Conquering new sources of supply. This is about working with suppliers to adopt materials or energy source with better performance, lower cost or improved environmental impact. An example would consist of contributing to the transition towards a fossil-fuel-free society.

- – Carrying out a new organization of an industry. This final Schumpeterian category is the most difficult to achieve and most powerful type of innovation. It consists of introducing such innovative products or services or using such revolutionary methods of production that the rules of the game in an entire economic sector are changed. Ford’s use of the assembly line to produce affordable cars in the early 20th Century is another example. So was Toyota’s introduction of its total quality movement in the 1980s. The introduction of personal computers in the 1980s or smartphones in the 2000s are instances of this powerful disruption.

The entrepreneurship definitions by Schumpeter assume that innovation is an intrinsic part of value creation. It does not exclude the phenomenon of “intrapreneurship” (Drucker 1994), that is, a manager who innovates in one of the above categories without necessarily owning shares in the firm. Like Schumpeter and Drucker, we believe that the entrepreneurship spirit could and should be part of any manager’s attributes, and that is the reason why intrapreneurs are the third target of this book.

According to this approach, it is not enough to create a new venture to be considered an entrepreneur. One must innovate. In our understanding, innovation is the process of addressing the unmet needs of a large enough group of people to sustain a business or organization. This definition is compatible with Schumpeter’s view without requiring radical or entirely new products, services or business models. Indeed, being first to market may result in failure to innovate.

To illustrate this underlying principle, let us take the case of one of the most innovative companies of the last decades: Apple. They have created what can be arguably considered one of the largest value-yielding empires in the history of mankind without ever having been “first to market”. They did not launch the first personal computer, the first portable music player, the first smartphone, the first tablet or the first smartwatch. But when they did launch each one of these groundbreaking product categories, they took deep care to address the unmet needs of a large audience, whether that need was user-friendliness, integration or elegant design.

Therefore, for the purposes of this book, innovation and entrepreneurship are profoundly intertwined. True entrepreneurship in the Schumpeterian sense requires more than simply creating a business: we must constantly try to understand and serve the ever-evolving needs of customers by launching better products or services, by improving our processes and by opening up new markets or segments. On the other hand, innovating in a well-established business is as important as creating new ones. Thus, the tools and insights offered in this book are also valuable to intrapreneurs.

1.2. Innovation and entrepreneurship education

Valerio et al. (2014) make a distinction between entrepreneurship and business management education. Typically, in a European business school, business management focuses on two key competencies: corporate management and enterprise development. In their first year of management, students are often exposed to the principles of organizational theory and its foundational sciences (psychology and sociology) while developing hard skills associated with corporate finance (based on financial mathematics) and accounting, risk management (including notions of statistics and probability), macro- and micro-economics. As this underlying knowledge is acquired, students are better prepared to understand organizational development, having disciplines such as strategic planning, innovation management, sales, marketing and accounting later in the program. Entrepreneurship education builds upon these competencies of enterprise development while adding specific disciplines about softer, “socio-emotional” skills, such as creativity, entrepreneurial vision, business model design, product management and business planning (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1. Business management versus entrepreneurship education (adapted from Valerio et al. 2014). For a color version of the figure, see http://www.iste.co.uk/lima/entrepreneurship.zip

Valerio et al. (2014) make a further distinction between entrepreneurship education (within the context of secondary and higher education institutions) and entrepreneurship training (for people outside the regular education system). Training programs are often offered by European governments to vulnerable, unemployed individuals in the hope of helping them create a self-employment business. Businesses created by these individuals are seldom innovative in nature. However, a second type of individual often seeks entrepreneurship training programs: inspired professionals who come across an opportunity to innovate. Training programs are also offered to active small business owners who wish to hone their entrepreneurship skills. Government-funded training programs hope to transform uninspired individuals into active innovators and regular SMB owners into developers of high-growth businesses (see Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2. Differences between entrepreneurship education and training (adapted from Valerio et al. 2014). For a color version of the figure, see http://www.iste.co.uk/lima/entrepreneurship.zip

These definitions and examples illustrate the main challenges involved in teaching entrepreneurship and innovation in the 21st Century. The speed of digital transformation has multiplied the tools to prototype product and service design, to create more efficient processes, to reach new markets beyond the barriers of time and space and to create entirely new business models, as the examples of Uber and AirBnB illustrate. In order to keep up with this transformation, students must experiment with in-class digital tools that facilitate self-learning, collaborating and sharing projects in a real-world setting.

There is a European consensus about the importance of teaching E&I. According to Fayolle and Gailly (2008, p. 572),

A recent work conducted by a European group of experts representing all EU member countries proposed a common definition [of entrepreneurship education]. The consensus reached led to the inclusion of two distinct elements: (1) A broader concept of entrepreneurship education which should include the development of entrepreneurial attitudes and skills as well as personal qualities and which should not be directly focused on the creation of new ventures; and (2) A more specific concept of new venture creation-oriented training (European Commission 2002).

We argue that in order to foster relevant “attitudes and skills” mentioned in the first part of this definition, we should include a series of digital tools and project-based learning approaches explored in this book. Rather than simply consider this as a process of “knowledge transfer” concerning opportunities to created new products and services (Hindle 2007), we propose a constructivist approach in which future entrepreneurs, intrapreneurs and innovators build their own knowledge from the practice of project-based activities. Indeed, the word “teaching” hardly seems appropriate in this process. As Fayolle and Gailly (2008, p. 574) further argue:

Given that entrepreneurship refers rather to individual initiative, creativity and sometimes innovation, it appears inadequate to favor the emergence of entrepreneurs or make a society more entrepreneurial by only giving lessons or “imparting knowledge”. In the definition proposed above, teaching appears to imply a degree of passivity from the learner. The word “educate” seems therefore more appropriate. Indeed, entrepreneurship education relates to the evolution of learning processes and methods from a didactical mode towards an entrepreneurial mode.

If Europe wishes to catch up with the USA in terms of entrepreneurship and innovation dynamics, it must start by appreciating the difference between E&I teaching and education. The latter implicates developing critical and creative thinking in the learner’s minds, whereas the former is based on lecture-centric approach that is less and less relevant as students can find information and tools by their own resources given the wealth of Internet media (massive open online courses or MOOCs, YouTube tutorials, social media discussion forums and the plethora of websites dedicated to the theme). That is not to say that instructional lectures are completely irrelevant. If operational “know-how” and higher-level “know-how-to-think critically and creatively” are the ultimate goals, it is also important to assure declarative knowledge (“know what” and “know why”) as a basis for intellectual autonomy. Thus, we do not suggest eliminating traditional teaching altogether but enriching it with more participative, bottom-up learning processes. Overall, we must not confuse ideal methods for teaching entrepreneurship and innovation with those traditionally used for management education, both in terms of contents and form (Johnson et al, 2006). When teaching entrepreneurship, professors must adopt the role and attitude of a facilitator and advisor rather than that of an instructor (Lautenschläger and Haase 2011). As Hills (1988) suggested (after looking into the attitudes of 15 of the most recognized American entrepreneurship teachers), entrepreneurship mentors must act and feel “entrepreneurial”. This has not always been the case: Bennett (2006) conducted a study of 141 teachers in entrepreneurship in England, concluding that many of them lacked entrepreneurship experience, reflecting on their traditional approaches to teaching the subject. These deficiencies can and should be compensated by specific teacher training programs aimed at giving them more direct involvement with the process of new venture creation.

1.3. Can entrepreneurship be taught? Towards a framework of E&I education

Since the first entrepreneurship courses were introduced in Harvard Business School in the 1940s, there has been a longstanding debate on whether entrepreneurship can be taught. Akola and Heinonen (2006) distinguish between the “art” and the “science” of entrepreneurship. According to them, the soft skills involved (e.g. creativity, innovative thinking) cannot be learned in school, they require practical experience. The “scientific knowledge”, however (e.g. business and management skills), can be taught.

This distinction seems rather artificial in our experience. Tacit knowledge involved in soft skills are indeed harder to teach, but active learning pedagogical approaches discussed in this book could help students experience “real-life” scenarios in the classroom. By applying concepts and frameworks to relevant situations and collaborating in small groups, we have experienced how students can become more creative, critical thinkers while developing better communication, negotiation and leadership skills. Thus, we fully agree with Peter Drucker (1994) that E&I can be presented as a discipline, which can both be learned and practiced. The issue therefore is not “whether” E&I can be taught or learned, but “how”.

Lautenshläger and Haase (2011) list a series of barriers to entrepreneurship and innovation education, such as the lack of uniform objectives and pedagogical content, overemphasis on the “traits of successful entrepreneurs” and the difficulty to measure impact on students. Fiet (2001) further argues that it is unlikely that students will face the same scenarios that teachers use in class to contextualize their concepts and that ideal entrepreneurial behavior examples from great innovators could actually have a “demoralizing” effect on aspiring students (who may feel they are “no Steve Jobs”).

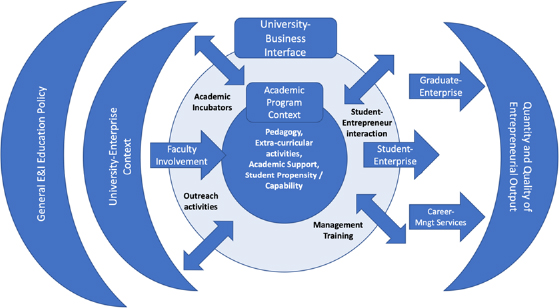

While all of these are real difficulties faced by entrepreneurship and innovation educators, we argue in this book that with an appropriate E&I educational framework, most of these barriers can be minimized or overcome. In this sense, Pittaway and Cope (2007) propose a general overview of the fundamental elements that must be present in a healthy relationship between entrepreneurship education institutions and the overall business ecosystem (Figure 1.3).

Figure 1.3. University–enterprise interface and the entrepreneurial ecosystem (adapted from Pittaway and Cope 2007). For a color version of the figure, see http://www.iste.co.uk/lima/entrepreneurship.zip

Pittaway and Cope’s framework can be read from left to right in terms of a basic input–process–output system. The starting point and one of the key elements of the European entrepreneurship ecosystem are the general E&I education policies from the regional and national governments. According to the “Entrepreneurship 2020 Action Plan”2 by the European Commission (published in 2012), the following topics were considered a priority expectation of European governments by entrepreneurs and business support organizations in the ecosystem:

- – Streamline new venture creation processes – reduce the number of administrative procedures, avoid duplication of tasks, speed up and simplify licensing and permits, optimize tax systems, increase social protection for entrepreneurs, raise awareness of government administrations about SME challenges, improve the quality and variety of government services for startups.

- – Facilitate transfers of business – improve legal and tax provisions for business transfers, improve information services for potential business transfer stakeholders, develop marketplaces to facilitate business transfers.

- – Develop more efficient bankruptcy procedures – give honest bankruptcies a second chance, develop or expand mentor programs to second starters, create more affordable procedures for business failure procedures, raise awareness against the stigmatization of failure, create specific financial incentives for second starters.

- – Support new entrepreneurs – improve business support services, facilitate ecological transition for existing SMEs, increase training, finance and internationalization support for high growth SMEs, offer better support to business innovation.

- – Improve access to finance – reinforce venture capital initiatives and loan guarantee, improve financial advisory of Enterprise Europe Network, reduce taxation for early stage ventures.

- – Develop youth entrepreneurial training and education – create a European hub or platform for entrepreneurship learning and share best practices for content development, implementation and measurement, embed entrepreneurial attitudes and skills at all educational levels (primary, secondary, vocational, higher education networks), incentivize youth to have at least one entrepreneurial experience at secondary education stage, develop and share a common guiding framework to support the development of entrepreneurship education institutions, increase funding to entrepreneurial education via European education funding programs, increase entrepreneurial training.

Specific actions were also aimed at increasing entrepreneurship and innovation rates among women, seniors and minorities.

The second level of Pittaway and Cope’s input phase is the “university-enterprise” context. We could “zoom into” this element using the Quadruple/Quintuple Helix frameworks developed by Carayannis et al. (2012) based on Etzkowitz and Leydesdorff’s original Triple Helix model (2000). In their original work, Etkowitz and Leydesdorff argued that university-enterprise relations could not be understood outside of the ecosystem in which they take place. Such ecosystem consists, as we have seen, not only of companies and higher education institutions but also of government policies that foster entrepreneurship and innovation. Carayannis et al. (2012) develop this ecosystem even further, as depicted in Figure 1.4.

Figure 1.4. The Quadruple/Quintuple Helix models (adapted from Carayannis et al. 2012).

According to this perspective, technology and knowledge are created both in universities (education system producing human capital) and in companies (economic system investing private capital, which in this chapter we designate as “entrepreneurship capital”). These, however, heavily rely on the incentives, disincentives and knowledge flows created not only by the government (political system with its policies, regulations and development programs) but also by the pressures of the public (media, NGOs, social institutions which provide legitimacy and trust through social capital) and the constraints from the natural environment (with increasing sustainability requirements).

Pittaway and Cope’s framework captures well the political, human and entrepreneurial capital elements of the Quintuple Helix model but fails to mention the importance of civil society (social capital emanating from the institutions mentioned above) and the increasingly important natural capital. Indeed, one of the constraints of innovation and entrepreneurship in Europe in the 21st Century is the conciliation of economic development with sustainability.

At the heart of Pittaway and Cope’s framework is the university–business interface. Leading into this process is the key factor of “faculty involvement” in outreach activities, development of academic incubation programs, student–entrepreneur interaction and basic managerial skills development. These efforts must be actively supported by the active pedagogy principles discussed in this book, as well as extracurricular activities, academic support programs and the identification of students with a high propensity/capacity to innovate. An alternative depiction of this core element in the framework is offered by Fayolle and Gailly (2008), as illustrated in Figure 1.5.

The authors differentiate between the ontological and educational levels of the problem. At the ontological level, before designing E&I programs, faculty members and other stakeholders (partners, government support agencies) should make sure they all agree on the meaning of entrepreneurship education, the adaptations that are necessary to the traditional education tools and the roles that each of them will play in this ecosystem. Then, at the educational level, we must understand the target audience, develop contents and methods adapted to that audience and establish clear metrics for assessment of skill acquisition by students.

Figure 1.5. Key questions in entrepreneurship education (adapted from Fayolle and Gailly 2008). For a color version of the figure, see http://www.iste.co.uk/lima/entrepreneurship.zip

Concerning these skills, Valerio et al. (2014) argue that any E&I program should focus on developing self-confidence, leadership, creativity, risk propensity, motivation, resilience and self-efficacy. Students must be led to become aware of their affinity with E&I mindsets and competences, and they need to understand how their business knowledge and skills must be adapted to the process of new venture creation.

In a literature review of 108 articles about entrepreneurship education methods, Mwasalwiba (2010) found that the most common approach remains the use of presentations, videos and lectures (26 articles). However, more active learning methods were also very popular, such as (by decreasing frequency in the literature): case studies (12), group work (10), business simulations (10), business plan creation (8), real venture creation (6), games and competitions (6), project-based learning, workshops (6) and study visits (4).

This abundance and variety of active learning methods in E&I learning is a sign that most teachers in this domain realize the limitations of traditional lectures when trying to develop the necessary attitudes and skills in this domain. In our article with Albertini et al. (2019), we have categorized three main objectives of E&I education initiatives in France (Table 1.1). This chapter will particularly focus on the second objective of the framework (develop skills and competencies).

Table 1.1. Examples of studies on the roles of entrepreneurship education in developing entrepreneurial intent (Albertini et al. 2019)

| Objectives | Examples | Academic studies | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Raise awareness | Competitions and challenges to foster the entrepreneurial spirit | Arlotto et al. (2012) | |

| Diagnosis tools to develop self-awareness and entrepreneurial vocation | Chené et al. (2011) | ||

| Junior enterprise – gateway to entrepreneurship | Barès et al. (2011) | ||

| Using guest lectures by star entrepreneurs in order to impact entrepreneurial intention among students | Boissin et al. (2007) | ||

| 2. Develop skills and competencies | Pedagogical approaches | Action-based pedagogy designed to construct credible scenarios based on simple ideas | Filion et al. (2012) |

| Hybrid programs with both academic and professional courses | Verzat and Granger (2012) | ||

| Building an entrepreneurial pedagogy, based on four principles: empowering learners, providing first-hand experience, cooperative learning and reflective learning | Fayolle and Verzat (2009); Surlemont and Kearney (2009); Lima et al. (2004); Toutain (2011); Lima and Fabiani (2015) | ||

| Implement active teaching: the case method, problem-based learning and project-based teaching | |||

| Content | Adapt contents to student needs; highlight the generic objectives, targets, methods/teaching content and impact indicators | Bechard and Gregoire (2009); Mwasalwiba (2010) | |

| Adopt a transversal, multidisciplinary and innovative approach; use creative methods to promote entrepreneurship | Sarow and Stuart (2013) | ||

| Teach ethical principles for socially responsible entrepreneurship | Fayolle and Toutain (2013) | ||

| Methods/means | Focus training on the learner’s ability to develop “know how”; using real-world situations to develop entrepreneurial competencies | Sarasvathy (2001); Aouni (2011) | |

| Substitute causal approaches (means to an end) by effectuation approaches (determining the possible effects based on the available means); relativize the power of predictive approaches and other myths about entrepreneur. | |||

| Stimulate taking risks in entrepreneurial situations (“situationist drift”) | Dervaux (2011); Bureau and Fendt (2012) | ||

| Bridging education and business worlds with experimental role-switching approaches such as “live my life” | |||

| Consider using innovative educational tools (use of videos, life stories, role plays, etc.) | Carrier (2009) | ||

| Introductory classes to initiate students in the world of entrepreneurship and innovation | Toutain and Salgado (2015) | ||

| 3. Provide support | Create a physical environment for developing entrepreneurial skills – incubator | Loué et al. (2008) | |

| Develop an entrepreneurial culture through networks: entrepreneurship hub, innovation support programs | Boissin and Schieb-Bienfait (2011) | ||

| Establish a network of financial support (venture capitalists, angel investment programs, training on the use of crowdfunding platforms) | Lam (2010) | ||

The pedagogical approaches listed in Table 1.1 are supposed to raise awareness, develop student vocation and improve their attitudes towards entrepreneurship (Boissin et al. 2007; Arlotto et al. 2012; Fayolle 2012). However, these initiatives often are fragmented (Verzat 2011) and confined within university walls, poorly connected with the entrepreneurial ecosystem (Verzat and Garant 2010). There have been attempts to integrate these initiatives in the main curriculum across European countries, creating a coherent approach to the content structure and how it is evaluated. The ultimate objective is to create a common background for evaluating and improving the quality of international entrepreneurial programs (Loué et al. 2008; Roeggiers 2012). Despite these attempts, a unified approach to evaluating the effectiveness of entrepreneurship programs remains an elusive ideal (Verzat and Granger 2012).

Some of these pedagogical approaches may seem confusing to both learners and teachers. Educational innovations often require a fresh mentality about the way we learn and teach, and resistances may appear from both sides of the fence (Verzat 2011). This resistance to change has several causes (Fayolle 2012): habit or inertia, fear of the unknown, perceived threats while facing new situations, denial, psychological stress, additional financial costs, hostility and perceived barriers from stakeholders. Indeed, entrepreneurship education should have a deep impact on attitudes if it is expected to change behavior; as such, it has sometimes been compared to a “cultural revolution” in teaching and learning (Chambard 2013). Furthermore, it must be noted that a good entrepreneurship program often may have the opposite effect on entrepreneurial intention: better knowledge of one’s self, one’s competencies and aptitudes may convince participants that they are not well suited to the entrepreneurship journey (Oosterbeek et al. 2010; Alis et al., 2014).

Other factors may affect entrepreneurial intention. Timing, for instance: students who are closest to graduation (and who are therefore more clearly confronted with the prospect of a steady job) are more prone to cite obstacles to creating a new venture of their own (Boissin et al. 2009; Hallam et al. 2016). Another factor is the initial level of entrepreneurial intention before being exposed to a formal training (Fayolle and Gailly 2009). Hence, in order to develop a common framework about the efficacy of entrepreneurial programs, we must consider learning objectives, assessment methods, skills and attitudes (Hofer 2010; Verzat 2011). We must also take into account cultural implications, institutional and contextual variables – political, economic and social (Fayolle 2012). Universities must make the teaching of entrepreneurship relevant by emphasizing success stories of local SMEs; this requires close interaction with its territory, in particular through partnerships with local businesses. Such university–enterprise interactions are mutually beneficial and reinforce the role of universities as agents of regional development (Kitagawa 2005). In brief, we must build an “entrepreneurial education ecosystem” (Toutain et al. 2014).

Whereas traditional lectures are necessary to impart “know what”, “know where” and “know who” and even “know why”, constructivist methods are more adapted to develop “know how” competencies. In Mwasalwiba’s survey (2010), the nine most frequent subjects in E&I were largely in this procedural knowledge domain: idea generation and opportunity discovery, business plan development, new venture creation process, risk management, marketing strategies, organization development, managing growth, finance and operational SME management.

1.3.1. The French case

According to the annual Global Entrepreneurship Monitor survey (GEM 2014), the “early-stage entrepreneurial activity” rate in France is relatively low (5.3%), even though according to the same source one French person out of three (28.26%) was aware of entrepreneurial opportunities around them. Several reasons are cited for this gap, such as the fear of failure, the economic crisis, a hostile environment, lack of entrepreneurial spirit and competencies. In order to overcome these obstacles, the French Ministry of Higher Education and Research has encouraged universities to develop a kind of “entrepreneurship campaign” aimed at promoting entrepreneurial activities. In recent years, as a result, many programs have been created in business or engineering schools as well as in other domains of higher education (Arlotto et al. 2011).

In 2014, the Ministry of Higher Education created 29 entrepreneurship networks all across the French territory. Called PEPITE (a French acronym that means both “seed” or “Pole For Student Innovation, Technology Transfer and Entrepreneurship”), these networks of higher education institutions are supported by the creation of the “entrepreneurial student” status, which extends social security and training benefits for French graduates below the age of 28. This was an important step towards the idea of building “entrepreneurial universities” as evoked by Clark (1998); according to this ideal, universities should have an entrepreneurial-centric culture as the basis for research and teaching, should be administratively more independent and financially more accountable, relying less on public funds. They must thus find a balance between the traditional academic values and a more market-oriented culture (Rinne and Koivula 2005; Shattock 2005). The Bill on Univeristy Liberty and Responsibility, which was voted in 2007 by French lawmakers, is part of the same trend. In this context, to foster entrepreneurship, vocations became one of the ambitions of the French university system in recent years.

Table 1.2. Examples of entrepreneurial initiatives in French universities encouraged by the PEPITE program

| Objectives | Examples | French university initiatives |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Raise awareness | Meetings with business leaders in various forms (conferences, forums, congresses, etc.) | Guest lecturers Vocational service Apprenticeship service Junior enterprise (student-run business consulting bureau) |

| Startup weekend | ||

| Organization of competitions | ||

| 2. Develop competencies | Entrepreneurial training; Course on new venture creation/SMB acquisition; business games, business model and business plan development tools | Undergraduate curriculum, continuing education programs |

| 3. Provide support | Mentoring new venture creation projects Mentoring SMB acquisition projects | Pre-incubators, incubators, accelerators, FabLabs, co-working spaces, enterprising student status, e-learning resources (entrepreneurial student degree) |

1.3.2. Enablers of entrepreneurship and innovation education

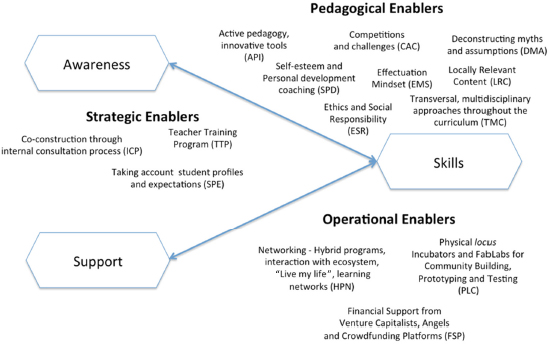

Figure 1.6 presents the framework derived from our conceptual and empirical investigation. The three key roles of the university are presented as a triangle (raising awareness, developing skills and providing support). Elements that impact all three dimensions are clustered under the “strategic enablers” tag. Those that have an impact on “awareness” and “skills” were dubbed “pedagogical enablers”. Finally, those in the intersection between “skills” and “support” were called “operational enablers”.

Foremost among the strategic enablers stands the notion of collaborative or consultative conception and development of entrepreneurship programs. Involving all stakeholders (internal and external) is necessary in order to ensure that the program will reflect a shared vision; at the heart of this consultation process is of course a debate with the students themselves, whose specific needs and expectations must be taken into account in order to better impact their attitudes and behaviors. Based on this diagnosis, a teacher-training program must be designed not only to update instructors on entrepreneurship best practices but also to help them better understand entrepreneurial attitudes and values, as well as project-based pedagogy and active learning resources. This process can be enriched by encouraging teacher engagement in the entrepreneurial ecosystem, visiting incubators and technology parks and exchanging their role with real-life entrepreneurs for one day (“live my life” approach).

Among the operational enablers, formal partnerships between the university and the innovation clusters should help consolidate these learning networks. Furthermore, the university should create at least one physical locus to facilitate face-to-face interactions among students and members of the entrepreneurial ecosystem. Ideally, this place should be a multi-purpose environment suitable for informal meetings, coaching sessions and workshops, and animated by weekly activities such as seminars, breakfasts with entrepreneurs and community building programs. It should be decorated in bright colors and mobile furniture, drawing inspiration from Silicon Valley open spaces that are designed to encourage creativity and well-being. It should also incentivize the “FabLab” culture, with prototyping tools such as 3D printers and sketching software. Finally, attention should be paid to the financial mechanisms available. If private investors and angels are not locally available, then the university could create an institutional program to award seed money to the best startups. At the bare minimum, there should be training programs on how to prepare a crowdfunding campaign using platforms such as Kickstarter or Indiegogo.

Figure 1.6. Framework for evaluating effectiveness of entrepreneurship education (Albertini et al. 2019). For a color version of the figure, see http://www.iste.co.uk/lima/entrepreneurship.zip

Among the pedagogical enablers, the use of innovative tools based on active learning and real-life projects should be a priority. Rather than having only traditional lectures based on slides, students should also be immersed in simulations, role-playing games, competitions and challenges. Myths and false assumptions about entrepreneurship must be deconstructed; lectures by former students who have created successful local businesses should dispel common misconceptions and demonstrate how any “normal” person can become an entrepreneur. This approach must be reinforced by group dynamics and coaching sessions aimed at developing the sense of self-worth concerning the student’s abilities to lead in an innovative environment. Due to the Cartesian training of students, they tend to reason in terms of cause-and-effect patterns that seldom match the complex reality of consumer needs and aspirations. They need therefore to understand the logic of effectuation inherent in principles such as Design Thinking and the Lean Startup approach in order to test their ideas sooner and let the market decide how products and services should be developed. They need to understand their role as “movers and shakers” of societal status quo and the ethical responsibilities that this implies. Finally, all of these initiatives must be transversal and multidisciplinary, involving diverse faculty members who clearly understand their role in creating an entrepreneurial environment throughout the curriculum.

We propose a diagnostic tool in the form of an online questionnaire (Appendix 2). The questionnaire uses a five-point Likert scale to determine the gap between ideal practices and the current perceived reality of Universities (which will be an average of the perceptions of the experts involved and may vary from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 5 (“strongly agree”). Figure 1.7 illustrates the evaluation of the University of Corsica entrepreneurship program by the same experts who participated in the qualitative study.

Figure 1.7. Enablers of the entrepreneurial environment at University of Corsica (Albertini et al. 2019). For a color version of the figure, see http://www.iste.co.uk/lima/entrepreneurship.zip

A quantitative analysis of the survey results indicates that Corsica’s greatest perceived weakness among the strategic enablers is the teacher training program or TTP (3.2 on the five-point scale). Among the pedagogical enablers, the effectuation mindset (EMS = 3.8) and ethics and social responsibility (ESR = 3.7) are the weakest spots. Among the operational enablers, finance support is the greatest perceived vulnerability (FSP = 3.5). This quick analysis suggests that in order to improve entrepreneurial intent among students, Corsican policy makers should focus their attention on improving teacher education programs that not only emphasize the tools and techniques for creating new ventures but also promote behavioral changes concerning effectuation and risk-taking attitudes. Moreover, these training programs need to underscore the importance of ethical behavior and the potential of social entrepreneurship as an opportunity to improve society. Finally, it seems clear from the data that Corsica’s entrepreneurship environment lacks financial support mechanisms, venture capitalists and angel investors. Attracting those stakeholders or creating state-sponsored programs would likely stimulate students to create new businesses.

1.3.3. Perspectives for the European ecosystem

The ultimate output of Pittaway and Cope’s framework (2007) is the quantity and quality of interactions in the entrepreneurship and innovation ecosystem, resulting in sustainable economic growth. As discussed in detail in this chapter, the European Commission has identified the right “input” elements in this framework: support E&I education, simplify the legal barriers to create and dissolve startups, strengthen the financial mechanisms that foster entrepreneurial activities and promote a culture of risk taking among first-time entrepreneurs and veteran venture creators, among other measures. According to Carayannis et al. (2012), this political/legal capital must be combined with social capital from the civil society. In that sense, media, non-governmental organizations and citizens must be made aware of the value of entrepreneurship and innovation to society. This will increase the social status of entrepreneurs and value-creating individuals, awakening vocations among not only the youth entering the higher education system but also unemployed or inactive people. It will also make current small business owners more aware of the importance of innovation in order to achieve sustainable growth.

Besides political and social capital as inputs, the higher education process must develop adapted programs to create human capital with the right mindset and skills. As seen in this chapter, this involves identifying the ontological specificities of E&I education before asking who, what, how and how-to-evaluate questions, as suggested by Fayolle and Gailly (2008). Concerning the central “how” question, we offer a set of pedagogical, strategic and operational enablers that, taken together, could help raise awareness, develop entrepreneurial hard and soft competencies and provide support to the development of E&I activities by venture-creating students (Albertini et al. 2019). One important element that is often forgotten in E&I programs is the fifth dimension of the Carayannis’ Quintuple Helix: sustainable development. In order to achieve sustainability (not only ecologically speaking but also in terms of long-term economic development perspectives), it is not only enough to understand the constraints of a fragile ecological environment but also to internalize deep ethical and moral principles that should be associated with the power of value creation.

If all the elements of these nested frameworks are considered, then we believe that the answer to the age-old question “can entrepreneurship be taught” is a resounding YES. Contrary to what Akola and Heinonen (2006) suggest, we have experienced how active learning pedagogy combined with the right academic and business environment and supported by relevant public policies can lead to the development of soft skills such as creativity, innovative thinking, communication and negotiation and leadership. The rest of this book will discuss such pedagogical approaches in depth.

1.4. Collaborative Interactivity learning principles3

Most modern educators would agree that students learn very little merely from listening to a teacher or watching his or her slides. According to Spencer (1991), people generally remember only 10% of what they read, 20% of what they hear, 30% of what they see, 50% of what they see and hear, 70% of what they say during a discussion and 90% of what they say while performing actions related to the speech content. This realization has inspired a century-old educational movement originally based on the cognitive development theories of Jean Piaget and Lev Vygotsky (Jonassen et al. 1999). Piaget found that humans create meaning by establishing an interaction between their experiences and their ideas. Vygotsky gave birth to the notion of “social constructivism” by emphasizing that learning is inherently a sociocultural process. These founders have inspired the notion of situated cognition, which postulates that knowledge is an inter-subjective construction mediated by social interactions and technological tools in communities of practice.

In my PhD thesis (Lima 2003), I have synthesized these theoretical foundations in a principle I called “Collaborative Interactivity” to express the two fundamental elements of social constructivism (interaction and collaboration). This approach has the following premises: (a) knowledge is mostly self-constructed, which means that it is not entirely transmissible; (b) the construction of knowledge results largely from symbolic action and manipulation, so learning is embedded in proactive interaction between the learners and the objects surrounding them (both conceptual and empirical); (c) knowledge is deeply linked to the context in which the action takes place; and (d) meaning is intrinsic to the mind of the knower, not only available externally. Corollaries of this definition are (d1) there are multiple world perspectives; (d2) learning is driven by problem situations of high significance for the learner; (d3) knowledge requires articulation, expression and representation of what is learned; (d4) meaning must be shareable and socially negotiated; and (d5) learning tools can increase the potential for reflection learning (Jonassen et al. 1999).

According to these premises, we must satisfy three interdependent conditions for the student to “make sense” of what he or she is learning or “construct” meaning: he or she must have some degree of active control of the learning process (it must be interactive), he or she must be led to articulate concepts around his or her experience (situated reflection) and he or she must be able to discuss his or her insights with others (collaboration). Furthermore, the context of learning must involve authentic, relevant scenarios he or she can clearly identify with. The concept of “Collaborative Interactivity”, as illustrated in Figure 1.8, aims at incorporating these three elements: interaction, reflection and collaboration in an authentic learning environment.

Figure 1.8. Concept of Collaborative Interactivity (adapted from Lima 2003). For a color version of the figure, see http://www.iste.co.uk/lima/entrepreneurship.zip

These elements of Collaborative Interactivity are consensually viewed by socio-constructivists as essential to the process of meaningful learning (Jonassen et al. 1999). According to this model, individual reflection must be accompanied by collaboration, or the inter-subjective negotiation of meaning. Social constructivists believe that group work offers a privileged space for exchanging experiences and creating a better understanding of reality. Lucena and Fuks (2000, p. 109) suggest that collaboration makes it possible to share a wide variety of learning and problem-solving strategies. This happens because collaboration puts individuals in a position to explain and convince others about their own cognitive processes, which facilitates metacognition or “learning about how I think” (Greer et al. 2000). According to Berlo (1999), a fundamental aspect of collaboration is the gain of multiple perspectives on the problems addressed. When two people interact, they put themselves in each other’s place, trying to perceive the world from each other’s perspective. As already discussed, particularly in poorly structured knowledge domains, such as social sciences, using different points of view is an adequate strategy to compose the inter-subjective reality.

The second dimension consists of stimulating the interaction between the learner, the learning objects and the facilitator as an effective way to construct knowledge. The expression “learning-by-doing” has become commonplace beyond pedagogical circles due to the fact that, as already discussed, much of the knowledge required to do analytical work is tacit, requiring experimentation and socialization to be internalized (Nonaka and Takeushi 1995). Information and communication technologies (ICT) can provide effective ways of interacting with concepts and empirical data. Business simulation games, interactive case studies and distance learning tools are just a few examples of how ICT can make the learning experience more interactive, even when dealing with a large number of participants. Other examples will be given at the end of each chapter.

Collaboration and interaction lead to individual reflection. In order to learn from their reflections, students need a certain structure or model of spatial information and establishing relationships between them. In addition to making the experiences more meaningful, Jonassen and his co-authors (1999) suggest that instigating students to systematize their own information in order to produce hypotheses makes them more involved with the resulting knowledge. When they simply receive and reprocess information given by third parties, they are far less committed. For this reason, the main objective of teachers in business schools should be to give students “thinking tools” that help them structure their problem-solving approaches. This book lists dozens of such tools in the form of analytical frameworks or “checklists for thinking”.

Unlike interaction, reflection and collaboration, contextualization is not an activity but a quality inherent in the Collaborative Interactivity environment, which increases the perceived relevance of the three elements. Research shows that learning done in a context close to the professional reality experienced by the learner results in knowledge that is more easily transferable to new situations (Jonassen et al. 1999). Selinger (2001, pp. 96–105) defines as authentic those tasks that lead students to recognize their previous experiences in the learning process. According to this principle, teachers should create problems that lead students to access previous knowledge and apply it as if he or she were acting as a professional (Matta 2001). Young (1995) emphasizes 10 essential attributes of “real-world” problems that must be respected in authentic learning contexts:

- – the solution of such problems requires the coordination of multiple cognitive processes, such as analysis, planning, problem identification and metacognitive reflection;

- – the credibility of the context increases the critical perceptions about viable situations;

- – solutions in these contexts tend to be negotiated inter-subjectively, facilitating collaboration;

- – technology can play a fundamental role in this process of interpersonal problem solving, facilitating communication and interaction among participants;

- – solving complex real-world problems often requires an interdisciplinary approach and should, if possible, involve people with different skills/ knowledge/biases;

- – such problems often give rise to multiple competing solutions; there are no “correct” answers, but different degrees of viability;

- – it is necessary to distinguish between relevant information and little useful information; real problems often bring a lot of superfluous information, and such insight is part of the skills that are expected to develop in professionals working in ill-structured knowledge domains, such as business and social sciences.

The enumeration of these attributes illustrates how a learning environment with authentic situations leads to the convergence of the other components of the Collaborative Interactivity model. Taken in isolation, none of them reach their full potential. When applied together, they create a rich, immersive learning experience that can be particularly effective in the domain of innovation and entrepreneurship education. Throughout this book, each chapter will finish with a few suggestions on how to teach specific E&I tools using the Collaborative Interactivity model.

- 1 Parts of this chapter have been adapted from our article published with Albertini, Thierry and Lameta about a Framework for Evaluating Entrepreneurship Education (Albertini et al. 2019).

- 2 Available at https://ec.europa.eu/docsroom/documents/10378/attachments/1/translations/en/renditions/pdf.

- 3 This section is based on a translation of excerpts from my PhD thesis entitled (in Brazilian Portuguese) “Potential of cognitive support of dynamic hypertextual interfaces” (Lima 2003).