Chapter 6

Large Value: Counterintuitive Cash Cows

IN THIS CHAPTER

![]() Evaluating value investing

Evaluating value investing

![]() Weighing value against growth for performance and risk

Weighing value against growth for performance and risk

![]() Recognizing ETFs that fit the value bill

Recognizing ETFs that fit the value bill

![]() Knowing how much to allocate

Knowing how much to allocate

![]() Choosing the best options for your portfolio

Choosing the best options for your portfolio

Why do American suburbanites gingerly cultivate their daisies, yet go nuts swinging spades or spraying poison chemicals at their dandelions? Why is a second cup of coffee in a diner free, but a second cup of tea isn’t? Some things in this world just don’t make a lot of sense. Why, for example, would slower-growing companies (the dandelions of the corporate world) historically reward investors better than faster-growing (daisy) companies? Welcome to the shoulder-shrugging world of value investing.

I’m talking about companies you’ve probably heard of, yes, but they aren’t nearly as glamorous as Microsoft or as exciting as Tesla. I’m talking about companies that usually ply their trade in older, slow-growing industries, like insurance, petroleum, and transportation. I’m talking about companies such as UnitedHealth Group, Procter & Gamble, ExxonMobil, and Exelon Corporation (providing electricity and gas to customers in Illinois and Pennsylvania).

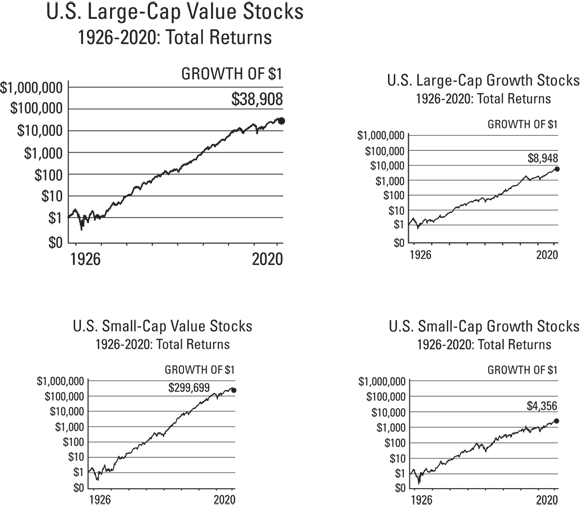

I see you yawning! But before you fall asleep, consider this: Since 1927, large-value stocks have enjoyed an annualized growth rate of roughly 12 percent, versus 10 percent for large-growth stocks — with roughly the same standard deviation (volatility). And thanks to ETFs, investing in value has never been easier.

In this chapter, I explain not only the role that large-value stocks play in a portfolio, but also why you may want them to be the largest single asset class in your portfolio. Take a gander at Figures 6-1 and 6-2. They show where large-value stocks fit into the investment style grid (which I introduce in Chapter 4) and the impressive return of large-value stocks over the past nine or so decades.

Pass the dandelion fertilizer, will ya?

FIGURE 6-1: Large-value stocks occupy the northwest corner of the grid.

Source: Colby Davis, RHS Financial, based on data provided by Ken French’s Data Library.

FIGURE 6-2: This chart shows the growth of $1 invested in a basket of large-value stocks from 1927 to the present.

Six Ways to Recognize Value

Warren Buffett knows a value stock when he sees one. Do you? Different investment pros and different indexes (upon which ETFs are fashioned) may define “value” differently, but here are some of the most common criteria.

P/E ratio: As early as 1934, Benjamin Graham and David Dodd (in their book with the blockbuster title, Security Analysis) suggested that investors should pay heavy consideration to the ratio of a stock’s market price (P) to its earnings (E) per share. Sometimes called the multiple, this venerable ratio sheds light on how much the market is willing to cough up for a company’s earning power. The lower the ratio, the more “valuey” the stock. (The P/E ratio as it relates to growth stocks is addressed in the previous chapter.)

P/E ratio: As early as 1934, Benjamin Graham and David Dodd (in their book with the blockbuster title, Security Analysis) suggested that investors should pay heavy consideration to the ratio of a stock’s market price (P) to its earnings (E) per share. Sometimes called the multiple, this venerable ratio sheds light on how much the market is willing to cough up for a company’s earning power. The lower the ratio, the more “valuey” the stock. (The P/E ratio as it relates to growth stocks is addressed in the previous chapter.)- P/B ratio: Graham and Dodd also advised that the ratio of market price to book value (B) should be given at least “a fleeting glance.” Many of today’s investment gurus have awarded the P/B ratio the chief role in defining value versus growth. A ratio well below sea level is what floats a value investor’s boat. Book value refers to the guesstimated value of a corporation’s total assets, both tangible (factories, inventory, and so on) and intangible (goodwill, patents, and so on), minus any liabilities.

- Dividend distributions: You like dividends? Value stocks are the ones that pay them.

- The cover of Forbes: Magazine covers are rarely adorned with photos of the CEOs of value companies. While growth companies receive broad exposure, value companies tend to wallow in obscurity.

- Earnings growth: Growth companies’ earnings tend to impress, whereas you can expect value companies to have less than awe-inspiring earnings growth.

- The industry sector: Growth stocks are typically found in high-flying industries, such as Internet commerce, computers, wireless communications, and biotechnology. Value stocks are more often found in older-than-the-hills sectors, such as energy, banking, transportation, foodstuffs, and toiletries.

Looking for the Best Value Buys

Many academic types have looked at the so-called value premium and have tried to explain it. No one can agree on why value stocks have historically outperformed growth stocks. (A joke I remember from my college days: Put any three economists in a room, and you’ll get at least five opinions.)

Some people say there is hidden risk in value investing that warrants greater returns. They explain that although the standard deviation for the two asset classes is about the same, value stocks tend to plummet at the worst economic times. This argument is not all that persuasive. During some serious market downturns, such as 2008 and again in 2020, value was hit harder than growth. But during other market downturns, such as the dot-com disaster of 2000 to 2002, value stocks proved much more buoyant than growth stocks. Others say that value stocks outperform growth stocks because of the greater dividends paid by value companies. Growth companies tend to plow their cash into acquisitions and new product development rather than issuing dividends to those pesky shareholders.

Here’s the best explanation for the value premium, if you ask this humble author: Value stocks simply tend to be ignored by the market — or have been in the past — and therefore come relatively cheap. When value stocks do receive attention, it’s usually negative. And studies show that investors tend to overreact to bad news. Such overreactions end up being reflected in a discounted price.

Taking the index route

Famous value investors like Warren Buffett make their money finding stocks that come at an especially discounted price. They recognize that companies making lackluster profits, and even sometimes companies bleeding money, can turn around (especially when Mr. Buffett sends in his team of whip-cracking consultants). When a lackluster company turns around, the stock that was formerly seen as a financial turd (that’s a technical term) can suddenly turn into 14-karat gold. It’s a formula that has worked well for the Oracle of Omaha.

Good luck making it work for you.

Making an ETF selection

The world of pure, indexed, large-cap, domestic value-stock ETFs includes at least 30 options from which to choose. The following four offer good large-value indexes at reasonable prices: the Vanguard Value ETF (VTV), Vanguard Mega Cap Value Index ETF (MGV), Schwab U.S. Large-Cap Value ETF (SCHV), and Nuveen ESG Large-Cap Value ETF (NULV).

I suggest that you read through the following descriptions and make the choice that you think is best for you. Whatever your allocation to domestic large-cap stocks (see Chapter 20 if you aren’t sure), your allocation to value should be somewhere in the ballpark of 50 to 60 percent of that amount. In other words, I suggest that you tilt toward value, but don’t go overboard.

What does it mean that one index fund outperforms another over the last three, five, or even ten years? Usually it’s tied to the expense ratio: The higher the expenses, the lower the return. And where the differential isn’t due to expenses, it’s often due to the make-up of the index, which may offer either more valuey stocks or larger- or smaller-cap stocks. A value fund that did especially well over the past decade — a decade where growth uncharacteristically clobbered value — may simply offer less valuey stocks. Should value stocks clobber growth in the next decade, these star index-fund performers will quickly lose their luster.

Vanguard Value Index ETF (VTV)

Indexed to: CRSP U.S. Large Cap Value Index (340 or so of the nation’s largest value stocks)

Expense ratio: 0.04 percent

Average market cap: $103.1 billion

P/E ratio: 21.9

Top five holdings: Berkshire Hathaway, JPMorgan Chase & Co., Johnson & Johnson, UnitedHealth Group, Procter & Gamble

Russell’s review: The price is right. The index makes sense. There’s good diversification. The companies represented are certainly large. The ETF has been around since 2002. No one has more experience with indexing than Vanguard. This ETF is a very good option, although I’d like it even more if it were a tad more valuey. (On the other hand, making it more valuey could increase turnover, which might increase costs and taxation.) All told, I like the VTV. I like it a lot. If you already own the Vanguard Value Index mutual fund and you’re considering moving to ETFs, this fund would clearly be your choice (see “The Vanguard edge” sidebar in Chapter 3).

Vanguard Mega Cap 300 Value Index ETF (MGV)

Indexed to: CRSP U.S. Mega Cap Value Index (140 or so of the very largest U.S. stocks with value characteristics)

Expense ratio: 0.07 percent

Average market cap: $151.6 billion

P/E ratio: 21.9

Top five holdings: Berkshire Hathaway, JPMorgan Chase & Co., Johnson & Johnson, UnitedHealth Group, Procter & Gamble

Russell’s review: This fund offers exposure to larger companies than does the more popular VTV featured earlier. Is bigger better? Could be. If you have small caps in your portfolio (which you should!), this mega cap fund will give you slightly less correlation than you’ll get with VTV. As a stand-alone investment, however, I would expect that the very long-term returns on this fund will lag VTV, given that giant caps historically have lagged large caps. Given Vanguard’s low expenses and reasonable indexes, either fund would make a fine holding.

iShares Morningstar Value ETF (ILCV)

Indexed to: Morningstar US Large-Mid Cap Broad Value Index (about 480 companies that qualify as value picks)

Expense ratio: 0.04 percent

Average market cap: $115.2 billion

P/E ratio: 25.9

Top five holdings: Apple, JPMorgan Chase & Co., Johnson & Johnson, Berkshire Hathaway, The Walt Disney Company

Russell’s review: I love the low price. It could be more valuey, and it would be if not for the inclusion of Apple stock. I’m not sure what it’s doing in a value index, but there it is. Morningstar indexers are clearly defining value a bit differently than the other indexers. As I mention earlier in this chapter, “value” can be identified using at least six different criteria.

Schwab U.S. Large-Cap Value ETF (SCHV)

Indexed to: Dow Jones U.S. Large-Cap Value Total Stock Market Index (made up of the more valuey half of the 1,000 or so stocks that comprise the Dow Jones U.S. Large Cap Stock Market Index)

Expense ratio: 0.04 percent

Average cap size: $80.8 billion

P/E ratio: 24.3

Top five holdings: Berkshire Hathaway, JPMorgan Chase & Co., Johnson & Johnson, The Walt Disney Company, Proctor & Gamble

Russell’s review: For the sake of economy alone, this fund, like all Schwab ETFs, is a good option. The management fee is one of the lowest in the industry. Most importantly, the index is a good one, and you can expect Schwab to do a reasonable or better job of tracking the index.

Nuveen ESG Large-Cap Value ETF (NULV)

Indexed to: Provides passive exposure to the 140 or so companies that make up MSCI’s TIAA ESG USA Large-Cap Value Index. (If you don’t know what ESG is, it stands for environmental, social, and governance, and you should turn to Chapter 17 to read more.)

Expense ratio: 0.35 percent

Average market cap: $74.9 billion

P/E ratio: 34.2

Top five holdings: Proctor & Gamble, The Coca-Cola Company, PepsiCo, Intel Corporation, Home Depot

Russell’s review: The average market cap is smaller than the other large-cap growth ETFs, and the expense ratio is higher — significantly higher. To date, however, Nuveen offers you the only option to invest in ETFs with style (value, growth, large, small) and to have a portfolio constructed with ESG considerations. Given that the portfolio holdings of this ETF differ appreciably from the other large-growth ETFs, you could see a significant difference in performance. Higher or lower? Probably, in the long run, higher. But that’s due largely to the smaller average market cap, which brings with it greater volatility.

Large-Cap Value ETFs that I wouldn’t go out of my way to own…

These ETFs aren’t the worst things you could own. But given the strengths of some of the other offerings, I don’t trade in these particular funds:

- Direxion Russell 1000 Value Over Growth ETF (RWVG): Expense ratio of 0.64 percent. Ugh. And this fund uses derivatives. And short stocks. UGH.

- First Trust Large Cap Value AlphaDEX Fund (FTA): Expense ratio of 0.60 percent, which is only “cheap” compared to the aforementioned Direxion ETF! It doesn’t use derivatives, but it does use a “tiered” indexing strategy that just sounds too much like a health insurance prescription plan.

- KFA Value Line Dynamic Core Equity Index ETF (KVLE): This fund has expenses of 0.58 percent annually and an unusual way of triaging value stocks from growth stocks. It was just born in 2020, so I’d give it quite a few years before investing. However, given the expenses, I doubt it will shine over the long haul. Expensive funds rarely do.