China’s Outbound Foreign Direct Investment

This chapter deals with the development of China’s outbound foreign direct investment (OFDI) activities over the last three decades. In addition to discussions relating to size and geographic distribution of China’s OFDI, we review the motives for Chinese companies to acquire companies abroad. Furthermore, China’s rules and regulations for outbound mergers and acquisitions (M&As) are discussed.

China has been playing an increasingly important role not only in international trade, but also in international capital flows both in the portfolio and foreign direct investment (FDI) forms since the 1990s. In this book, we only focus on OFDI by Chinese enterprises. Even though portfolio and direct capital flow to and from China are significant, we avoid discussions of these topics because they are outside the scope of the present book.

At the start of 2011, more than 13,000 Chinese entities had established roughly 16,000 overseas enterprises in 178 countries (regions) (Ministry of Commerce of China 2011). In 2016, the Chinese companies invested USD170.11 billion in 7,961 enterprises in 164 countries and regions (Xinhua 2017).

The status of China as the fifth-largest international foreign direct investor ($74.645 billion) in 2011 changed to the second largest ($183.100 billion) in 2016 (UNCTAD 2017a).

Table 14.1 shows the global distribution of the outward foreign direct investment1 flows from China for 2005 to 2010, and 2015.

Table 14.1 Global distribution of China’s outbound foreign direct investment flows (USD billion): 2005 to 2010, 2015

Source: Ministry of Commerce, People’s Republic of China (2013) for 2005 to 2010 and National Bureau of Statistics of China, 2016 for 2015.

To gain a better appreciation of the geographic distribution of China’s overseas direct investments (ODIs) by countries, we refer the reader to Table 14.2. The table shows the top three recipients of Chinese direct investment by continents in 2015.

Table 14.2 Top recipients of China’s foreign direct investment by continents in 2015

Source: National Bureau of Statistics of China (2016).

We make several comments concerning the investments in Table 14.2. First, the capital outflow from China to Hong Kong was almost 90 billion dollars in 2015, which is the largest sum of capital flow to Asia, which constitutes 83 percent of the total capital outflows to the continent. Second, the large outflow of funds to Singapore may be due to many Chinese citizens’ investments in Singapore as a method of immigrating to that country. Second, we note that the capital flows to Cayman Islands ($10.21 billion) and Virgin Islands ($1.85 billion) are relatively much larger than the flows to other countries, with the exception of Hong Kong. These countries are referred to as offshore financial centers (OFCs) or tax havens.2

One explanation for the interesting phenomenon of large capital flows from China to the OFCs is that foreign private equity firms in China, as well as Chinese firms, transfer funds to offshore companies as special purpose vehicle enterprises in preparation for cross-border acquisitions or initial public offerings of shares of the Chinese enterprises worldwide. The roundabout method of investment is the method of choice in those countries where high political constraints on FDI exist. Moreover, a change in the stock market regulation in Hong Kong in December 2009 allowed foreign companies including the Virgin Islands-based companies to list their stocks on Hong Kong Stock Exchange. Accordingly, Hong Kong Stock Exchange is used as an important channel for foreign equity firms in China to transfer funds from the Chinese financial market (Hempel and Gilbert 2010). Additionally, the significant capital flow to Hong Kong as well as to Singapore might be in conjunction to China’s internationalization of renminbi efforts, with Hong Kong and Singapore as important financial centers for the investment banks issuing bonds for the global enterprises that are denominated in renminbi (Subacchi 2017).

In addition to the increase in global capital flows and China’s outbound capital investment in recent decades, an increasing number of enterprises from the emerging market countries have become active in cross-border M&A activities beginning in the early 1990s. The emergence of these enterprises in the international M&A markets is motivated by the desire to achieve competitive advantage by acquiring resources such as natural resources, brands, technology, and management know-how.

Among those enterprises from the emerging markets, the Chinese enterprises, mostly state-owned enterprises (SOEs),3 have become prominent players in the international M&A scene in recent years. Table 14.3 shows the number and value of outbound M&As of mainland state-owned and privately owned enterprises (POEs) for 2011 to 2015. As the numbers in the table indicate, the number of foreign acquisitions by the SOEs is substantially less than the acquisitions by the POEs, but the size of the acquisitions by SOEs outweighs the size of the acquisitions by the private companies. This fact has led to some national security concerns for the United States and European countries, which we would discuss in next chapter.

Table 14.3 Number and value of outbound M&As by mainland state-owned and privately owned enterprises (values in billion USD)

Source: Brown and Chan (2017).

The reasons for the prominent role of China’s SOEs in foreign acquisitions include the size of acquiring firms (state enterprises are usually very large), government support of foreign acquisitions through preferential financing arrangement through state-owned banks, and profitability of SOEs (Song, Yang, and Zhang 2011).

The data in Table 14.4 show a totally different picture of the overall China’s outbound M&A. While the data in Table 14.3 show only outbound M&A transactions from mainland China, the data in Table 14.4 indicate the M&A deals that have originated by enterprises in the mainland as well as in Hong Kong.

Table 14.4 Number and value of outbound M&As by Chinese and Hong Kong enterprises

Source: Institute of Merger and Acquisition (2017).

According to the data in Table 14.4, both the number and size of the transactions have a positive trend line and have been increasing with minor variations. The rate of success4 of the M&A bids of Chinese firms during 1982 to 2009 (a total of 1,324 acquisition attempts) is 51.2 percent compared with the success rate of U.S. firms (76.5 percent), and the worldwide average rate (68.7 percent), as well as that of some emerging countries, such as Brazil (70 percent), South Africa (72 percent), India (62.8 percent), and Russia (59 percent) during the same time span (Zhang and Ebbers 2010).

Geographic Distribution of Outbound M&As by Chinese Companies

According to survey results (Hasting 2013), three regions of the world are areas of top interest for China’s outbound M&A activities. Investments in these regions include Asia-Pacific, Europe, and North America. Table 14.5 shows the geographic distribution of China’s outbound M&A investment between 2013 and the first 11 months of 2016.

Table 14.5 Regional distribution of China’s outbound M&As, percentages of the total outbound investment

*Includes January to November 2016 only.

Source: KPMG (2017).

According to the data in Table 14.5, the size of China’s outbound investment in acquiring companies in Africa and Asia between 2013 and November of 2016 remained relatively stable. However, one observes a re-orientation of China’s investment from Europe to North America during this period. The size of Chinese acquisition in North America has increased from 7 percent of the total outbound M&As of China in 2013 to 49 percent in 2016, while China’s acquisitions in Europe has decreased from 54 percent in 2013 to 19 percent in the first 11 months of 2016. During the same time, China’s acquisitions in Latin America has decreased drastically from 13 percent of the total to only 3 percent. After a peak of acquisitions in Oceania in 2014, China’s M&As in that continent dropped to only 2 percent of her total outbound M&As.

It is interesting to note that despite national security concerns of both U.S. and Canadian governments about foreign, including Chinese, acquisitions of enterprises in the critical industries of their respective countries, China’s acquisition in North America has increased (Squire Sanders Global M&A Briefing 2013).

Sectoral Focus of Outbound M&A by Chinese Companies

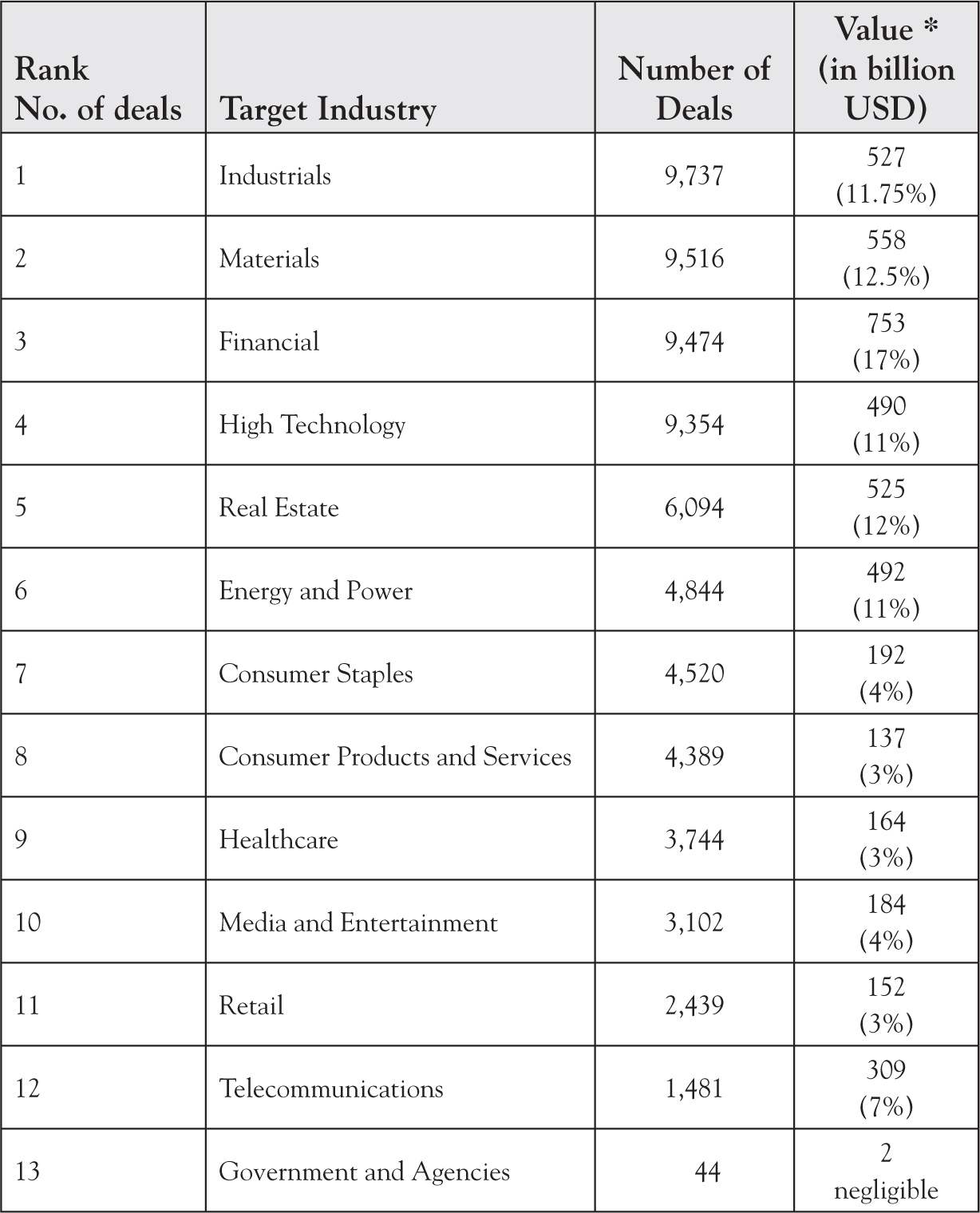

Table 14.6 shows the distribution based on the sum of China’s M&As during 2000 to 2016 according to the industries. As is shown in the table, China has acquired foreign enterprises in a variety of industries. However, in terms of value, the largest percentage of the total acquisitions has taken place in the financial services industry, followed by materials, industrial, and high-technology industries.

Table 14.6 Number and size of China’s outbound M&As according to Industries: 2000 to 2016

*Percentages do not add up to 100 percent due to rounding.

Source: Institute of Merger and Acquisition (2017).

Energy and resource industries were the primary targets of interest for China’s outbound M&As until the last few years. This is due to the rapid, persistent economic growth of China, and the adoption of a policy of reducing reliance on coal as a high carbon-based source of energy to reduce environmental pollution by the Chinese government (Squire Sanders 2013).

Factors Contributing to Outbound M&A Activities by Chinese Enterprises

A review of the literature dealing with reasons for cross-border M&As reveals several motives that are common with domestic M&As including strategic moves (capture synergy, capitalize on company’s core competency), entry into a new market, achieving economies of scale, and personal, that is, executive hubris and malfeasance. In addition to the listed motives for domestic M&As, cross-border M&As have another motive. Many corporate executives consider cross-border M&A as a method of diversification of risks associated with market volatility and changes in governmental policies. Risk diversification is believed to increase innovation that is associated with cultural diversity, which promotes globalization synergies (Larsson and Finkelstein 1999; Olie 1990).

The goal of M&A transactions is capturing synergies that are to be found in combining the companies. Specifically, research shows that the choice of M&A as a mode of entry into international markets is influenced by firm-level, industry-level, and country-level factors. Factors at the firm level consist of multinational and local experiences, product diversity, and international strategy. Industry-level variables include competitive capabilities such as technological intensity, advertising intensity, and sales force intensity. Finally, country-level factors consist of variables such as market growth in the host country, cultural differences between the home and host countries, and degree of risk aversion of the acquiring enterprise (Shimizu et al. 2004).

Recent surveys of Chinese executives, however, identify the specific motives by Chinese acquirers of foreign enterprises. For example, an event study by Boateng, Wang, and Yang (2008) using data from 27 Chinese cross-border M&A deals that took place by the purchase of stocks of target firms in the Shanghai and Shenzhen stock markets during 2000 to 2004, identifies the following strategic motives for the transactions that appear in Table 14.7.

Table 14.7 Motives for international M&A of Chinese enterprises

Source: Boateng, Wang, and Yang (2008).

Additionally, the findings of a survey of 100 executives from Greater China5 who had engaged in outbound M&A activities identified the following top five motives for their acquisitions (Deloitte 2013c).

- China’s need for secure natural resources

- Continuing globalization of Chinese SOEs

- Euro zone sovereign debt crisis

- Renminbi internationalization

- Chinese government’s going-out policy, which encourages outbound M&A activities of large Chinese enterprises by provision of bank financing for cross-border M&A transactions at preferential interest rates

It is also reported that for many Chinese overseas investments, high profits are not the main goal. The important motivating forces for China’s outbound direct investment (ODI) including outbound M&As are acquiring technological capabilities of advanced economies and the natural resources of developing economies (Wang and Huang 2011).

The Role of Government and Information in Growth of Outbound M&As

Government regulations and cultural differences might have played important roles in the further growth of Chinese outbound M&As. A recent opinion survey of 100 corporate executives, investment bankers, and private equity executives based in the United States and Greater China (Mainland, Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan), who had executive experiences in M&A transactions in entertainment, advertising, and digital media, showed that the respondents found government regulations the most significant obstacle in sustained growth of cross-border M&A activities in their industries (Manatt, Phelps & Phillips, LLP 2013). The second most important obstacle to the further growth of M&As in these industries was information. The American executives perceived inadequate information for the adequate due diligence of target firms in China as a major issue. At the same time, the Chinese executives believed that Americans seek too much information when their enterprises wish to acquire a U.S.-based firm.

For example, an executive of a U.S. private equity firm based in Shanghai had the following comment concerning the Chinese view of American standards for transparency in M&As: “Disclosure requirements in the United States are not acceptable for Chinese companies, and the standards seem unnecessarily high. Sources of financing and long-term strategies are very confidential, and when this information is sought, deals tend to fail” (Manatt, Phelps & Phillips, LLP 2013, 17).

Even though these views were expressed by the executives in entertainment, advertising, and digital media, one could infer from them, in general, that American and Chinese executives in all industries share the same perceptions. These results have ramifications with respect to the applicability of the procedures for M&As that were delineated in the earlier chapters of the book Volume-I for outbound M&As by Chinese companies. Moreover, the obstacles seen by the Chinese executives perhaps are not confined to acquisitions in the United States. Perhaps, they have the same concerns about acquiring firms in other developed countries. In fact, our discussions of Chinese experiences in FDI in Australia, and acquisition of a company in Italy (both in Part III of the book) confirm the view expressed here.

The Role of the Government of China in Outbound M&A Activities of Chinese Enterprises

Two sets of internal factors have shaped the policy of the government of China to promote M&A activities of select Chinese SOEs. The first factor is the existence of many large, inefficient in terms of profitability, but not employment generation, and monopolistic SOEs. These monopolies lack competition in internal markets and are protected by the government from international competition by being large SOEs. Therefore, in the past, these enterprises were content with the status quo of receiving support and privileges from the Chinese government and had no incentive to gain a competitive advantage on a global scale by acquiring technological and marketing capabilities. By following the policy of encouraging OFDI through M&As, the government of China aims to force the select monopolistic SOEs to become globally competitive. Internationalization of selective activities and industries in China is intended to promote value-chain upgrading and integration, acquiring access to and reducing the cost of raw materials, as well as acquiring tangible and intangible assets such as technology, brand names, and marketing capabilities (Sheng and Zhao 2013; Sauvant and Chen 2014).

The second factor is pressure by firms, most of which are private enterprises, which seek additional support from the Chinese government to promote OFDI through easier financing, research and development subsidies, stable fiscal policy, and human resource development (Sauvant and Chen 2013).

China’s OFDI policy evolved in five stages since economic reforms in that country in 1979. These stages include (Huang and Austin 2011):

- Gradual internationalization (1979 to 1985)

During this phase, China formally recognized the legality of international investment by allowing companies to establish offices and firms abroad. In 1983, the State Council established the Ministry of Foreign Trade and Economic Cooperation as the government agency in charge of OFDI.

- Government encouragement of overseas direct foreign investment (1986 to 1990)

During these years, the government actively encouraged overseas investment by Chinese SOEs.

- Expansion and regulation (1991 to 1998)

Due to a domestic surge in the inflation rate and several failed overseas investments, the Chinese authorities adopted policies to control overseas investments by SOEs in 1991. However, after the collapse of the former Soviet Union and economic liberalization in the Eastern European countries, mostly for political reasons, the State Council encouraged SOEs to trade with and invest in these countries in 1992.

- Going-out period (1999 to 2001)

This is the period in which China adopted a set of policies to encourage international investment, including establishing overseas processing and assembly operations of SOEs. The encouraging policies were mostly in response to the Asian Crisis of 1997 to 1999, during which China attempted to boost exports by relying on domestic low labor cost and less expensive overseas raw materials and energy resources. These policies set the stage for future development of Chinese OFDI.

- The post-WTO (2002 to present) period

In 2002, the government of China (State Council) emphasized the going-out strategy and considered it an important component of the overall long-run economic reform and liberalization policy of China. The policy statement further encouraged Chinese firms to invest overseas to gain technological and marketing capabilities and become globally competitive.

External Constraints for Chinese M&As

Chinese enterprises operating abroad face several challenges. These challenges include cultural distance, the divergence between fields of competencies of merging companies, changing market conditions, and over-optimistic view of market size. We will discuss these issues in depth in the next chapter.

Summary

This chapter dealt with size and geographic distribution of Chinese OFDI including outbound M&As of Chinese enterprises. We discussed motivations for overseas acquisitions of China’s SOEs and historical development of the Chinese government policy of promoting and encouraging outbound investment by Chinese enterprises.