chapter 18

Manage change

Leadership is about taking people where they would not have got by themselves. That means that change is at the heart of leadership. It is not enough for a leader to simply maintain or improve things. That is what any manager should do and it is very hard work. A leader will make a difference by changing how things work and moving towards a new future perfect.

In theory, we should all like change. Change is what brings about progress and prosperity: new technologies and greater efficiencies that link the global economy.

In practice, we like it when other people and firms change, which will benefit us. When we have to change, suddenly change becomes a lot less attractive. Change is no longer about opportunity, it is about risk. Change means changing how we work, perhaps who we work for, and where we work and what we do. We have to learn new rules of survival and success, which may or may not be good for us. The greater the change, the greater the perceived risk and the greater the passive and active resistance becomes.

“If you want to make real change, you will face real resistance.”

So, if you want to make real change, you will face real resistance. This alters the definition of leadership from ‘taking people where they would not have got by themselves’ to ‘taking people where they do not want to go (to start with)’.

The great mistake in contemplating change is to think about it as a rational process, which can be captured in neat Gantt or PERT charts, the standard tools of project management. The reality is different. Change means personal change and that makes the change process highly emotional. Change also means changing the organisation – changes in the pecking order mean that change is also a highly political process.

“Change means personal change and that makes the change process highly emotional.”

If you want to make change work, you have to manage the change process on three levels:

- •rational

- •political

- •emotional.

The assiduous project manager will work in the rational world of the project. As a change leader, you have to work with the political and emotional agendas of colleagues to effect change. ‘Working the political and emotional agendas’ sounds vague and slightly undoable. Much of it comes down to experience, which does not help much if you do not have the experience. Even if you do have the experience, it pays to have something more structured than your innate genius and intuition to rely on when it comes to making change. What worked last time may not work in different circumstances this time.

In practice, there are three tools that can help maximise your chances of success:

- 1Setting up change to succeed.

- 2Managing your change process.

- 3Managing your change network.

Setting up change to succeed

Most sane people do not enjoy change. Change implies uncertainty and risk. Even if I can succeed currently, how do I know that I can succeed in a new environment with a new boss doing new things? The less control over the change I have, the more I am likely to fear it. So, change is dominated by the FUD factor:

- •Fear

- •Uncertainty

- •Doubt.

The only people who do not suffer from the FUD factor are CEOs, senior leaders and consultants. They are able to control the change and they know how they intend to benefit from it.

In practice, most change programmes succeed or fail before they even start. As a leader, your crucial role is to make sure that change is set up for success, not failure. You may think this takes too much time, but it is time well invested to assure success. Over the years, one simple formula has been a constant predictor of change success or failure. Here it is, in all its spurious mathematical accuracy:

V + N + C + F ≥ R

V = Vision

This is not a ‘save the planet’ type vision. This is your future perfect idea. Show how your unit, firm or organisation is going to be different and better as a result of the change. This is your idea of the IPA agenda. To make the vision compelling, make it relevant to each person. Show how they have a role to play in the change and how they will benefit from the change.

N = Need

There has to be a perceived need to change, both for the institution and for the individual. Show that the risks of doing nothing outweigh the risks of doing something. Fear is often a powerful motivator for change. Increasing the fear of inaction is effective although unkind. CEOs often do this by creating a ‘burning platform’. Essentially, they argue that if there is no change, then the firm will be put out of business by competition, regulators or technology. The risk of change suddenly becomes low compared with the risk of losing your job. The start of the pandemic in 2020 demonstrated just how far and fast firms can change when there is a genuine burning platform.

C = Capacity to change

It is no use having both the vision and the need if the organisation lacks the skills or resources to change. Your team wants to know that they can make the journey from today to tomorrow successfully. Your capacity to change rests on two pillars. First, you need the resources to make it happen – you need the budget, team and top management support for it. Second, you need credibility. If a new change initiative is announced every six months and forgotten three months later, your latest initiative will be politely ignored. Demonstrate that this change is for real, which brings us on to first steps.

F = First steps

We live in a world of instant gratification. We want to know that we are backing a winner. Use this to your advantage. Seek out some early wins – some early signs of success that will bring all the doubters and fence-sitters on board. Create a sense of excitement; trumpet any progress loudly so that you appear to be at the head of a bandwagon. Let others join your bandwagon.

R = Risks and costs of change

The risks of change are normally dealt with by the standard corporate infrastructure of risk logs, issue logs and mitigating actions. These are useful in a limited way. They deal with the rational risks of change, which most managers are comfortable with. But the real risks of change are not rational, they are emotional and political. The emotional risks are about individuals who feel threatened by change. The political risks come from challenging the status quo, threatening the status of other units and generally disrupting the organisation.

Emotional and political obstacles are hard to spot. Normally, they are hidden behind a whole raft of rational objections to change such as ‘This will cost too much’ or ‘Customers will hate it’. These are camouflage for the real risks, which are ‘I feel threatened by this’ and ‘My unit is threatened by this’. If you deal with the rational objection, you miss the point and simply get stuck in an irrelevant and unwinnable debate. Take time out in private with each individual to understand and deal with their real agenda, and you will find that the rational objections mysteriously disappear of their own accord.

“Build up the need to change and the risks of doing nothing.”

As a leader, it pays to work the whole agenda. Constantly remind people of the vision and relate it to their needs. Build up the need to change and the risks of doing nothing. Find some early successes to keep people encouraged and make sure that there is enough capacity to support the change. All of this needs to be balanced against risk reduction: few people truly enjoy risk. The greater the perceived risk, the greater the resistance to change. Make the change very low risk and no one will get in your way.

Managing your change process

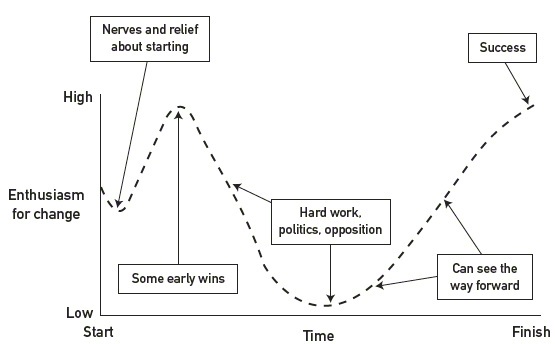

Project managers can manage the technical and rational aspects of change. As a change leader, you must manage the political and emotional consequences of change. Most significant change programmes go through a predictable emotional and political cycle, outlined in Figure 18.1.

If you have used the change equation successfully, then there will be some early enthusiasm for change. Some early wins bring more of the doubters on board and everything starts to look good. It is at this point that things start to go wrong. After the initial flush of enthusiasm dies away, slowly people start to understand the scale of the change required. They start to see the logical consequences of change. The exciting vision of the change you painted becomes obscured by the reality of the effort and risks involved.

There is rarely one event that triggers collapse. Usually, the change slowly meanders into a swamp of despair. The fair-weather friends who hopped on board at the first sign of success are hopping off at the first sign of trouble. They now create distance between themselves and your change. They may offer advice, but it is poisoned advice. Take their advice and then they will claim they turned the programme around. Refuse the advice and they will have the ammunition to show that you failed because you refused the advice. Suddenly, you can start to feel very lonely and very beleaguered.

Inevitably, prevention is better than cure for the mid-life crises of change. If you have put in the right preconditions for success, in terms of both project management and the change agenda, you will pull through. If the change was started prematurely, you may fail. There will not be enough belief in the vision or enough political support to overcome the opposition to change.

Curiously, the valley of death is essential to most successful change programmes. It is only in the valley of death that people fully realise the scale of the change they will need to make. Opposition to change is the surest sign that they are at last taking the change seriously, that they are engaged. Do not avoid the valley of death: seek it out.

In most major changes I have started, I have alerted the client or the sponsor to the change cycle and the valley of death at the start. If they know it is coming, they worry about it less, they realise it is natural and are ready to work through it. In several cases, the CEO has kept on asking, like a child on a long journey, ‘Are we there yet? Is this it? Have we got to the valley of death yet?’ The valley of death experience is uncomfortable but important. It is the moment when everyone realises that they can no longer continue with the old ways, even if they do not yet know what the future holds. This is when everyone is really grasping reality and is ready to move on.

“Leaders look to the future: keep your eyes fixed on the end goal and figure out the way of getting there.”

In the valley of death, followers give up. Leaders look to the future: keep your eyes fixed on the end goal and figure out the way of getting there. At a time when everyone else is seeing problems, you will stand out by offering solutions and actions. In this slough of despondency, people want solutions. The valley of death is your moment of truth, it is when you prove your capability and it will be when you learn and develop the most.

If all this does is give you some hope next time your change effort hits a crisis, then it has at least done some good. Remember, the difference between success and failure is often no more than persistence.

Managing your change network

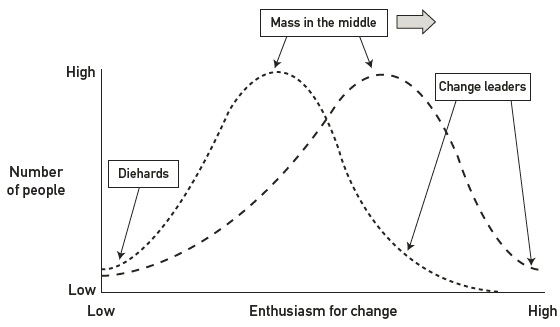

There is one big catch in setting up change to succeed. Leaders often want everyone to join their jolly bandwagon. Normally, this is not possible. There will always be some diehards who would resist anything. The successful change network consists of those people who collectively have the power, skills and resources to assure the success of the change. In addition, the change leader needs the critical mass of the organisation to be supportive. It is a trap to try to engage the whole organisation. The challenge can be seen in Figure 18.2.

This figure shows that most people feel pretty indifferent to the idea of change in principle. In practice, their enthusiasm will wax and wane depending on where they are in the change journey. But the bell curve effect will always be present.

There are always extremes at each end of the change bell curve. At one end are the change enthusiasts whom you can recruit as the active leaders and early adopters of change. At the other end, some will always resist. Do not waste time on them. Let them see that the change is succeeding and allow them to make up their own minds. They will start to feel lonely, left on the platform after the change train moves off. They can decide to leave or get on board. If they want to protest by lying down on the tracks in front of the train, let them know the train will not stop anyway. The change resisters can consume a disproportionate amount of your time and effort. In practice, you need to move the mass of people from neutrality to mild acceptance of change. Again, do not expect everyone to become change enthusiasts.

Achieving critical mass

At one chemicals company, the plant manager was frustrated that he could not implement a new set of working practices. We were asked to help. We soon heard loud objections to the whole change idea, expressed very forcibly. They used every reason to object, from cost to work–life balance to health and safety to threats of walkouts. But we found the objections were all coming from a small group of staff and managers in the power plant. Most other people were quietly supportive, but felt overawed by the loud-mouthed middle managers. And the plant manager had let himself become hostage to them – they had secured an effective veto over his plans.

Instead of focusing on the objectors, we focused on the supporters. As we started to implement the changes in the more supportive areas, people realised they liked the changes and became bolder about supporting them. We did not need to negotiate with the objectors – one by one they made their own decisions. Some got with the programme; some got out. As a change leader, do not try to please all the people all the time – you will get nowhere.

Aside from the mass of people, you must build the right power network in support of change. Building networks and alliances is essential to your success in the middle of the matrix and is the subject of Chapter 32.