The first stage of the risk assessment process is that of risk identification, the purpose of which is to determine the threats or hazards that could cause loss or damage to an information asset, to identify any vulnerabilities exhibited by the information asset and to determine the possible impact or consequences to the information asset.

Regardless of whether or not the risks identified fall within the remit of the organisation, they must be included in the assessment, even though the root cause may remain hidden.

Just to recap:

- The impact or consequence of a threat or hazard acting on an information asset is the result of that threat or hazard taking advantage of one or more vulnerabilities that are present within the information asset.

- The likelihood or probability of the threat or hazard succeeding in this depends on the type of threat and any vulnerabilities exhibited by the information asset.

- The risk is the combination of the impact or consequence on the information asset combined with the likelihood or probability of the threat or hazard successfully taking place.

Looking slightly deeper into this, we should also take into account the motivation for the attack for certain types of threat – where an attacker either wishes to obtain or change information (confidentiality or integrity) or to deny access to information asset (availability).

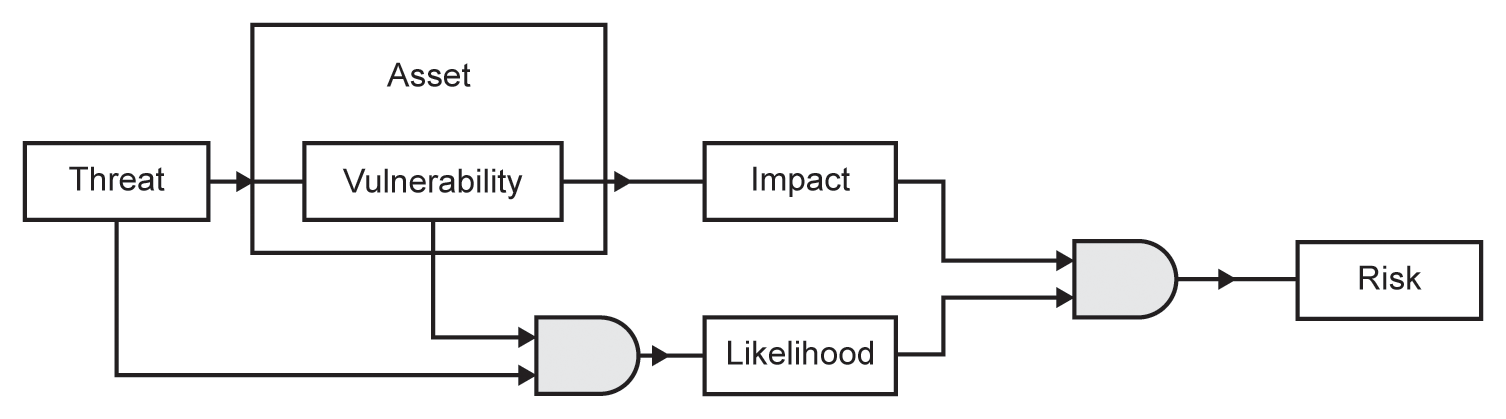

In the diagram at Figure 4.1, we can see that risk is the result of combining impact and likelihood. The impact is determined by a threat exploiting a vulnerability within an information asset, and that the presence of both threat and vulnerability give rise to the likelihood.

Now let us take a quick look at the more detailed process of risk identification.

THE RISK IDENTIFICATION PROCESS

Risk identification begins with identifying the information assets that are relevant to the organisation. This is almost certainly the most crucial part of the whole process – failing to identify an asset at this stage will mean it is never risk assessed, and it is vital that, along with the asset itself, an asset owner is identified. For some assets, this will be immediately obvious, whereas for others a senior management decision may be required in order to allocate ownership of the information asset to a suitable person or team.

Once the information assets have been identified, the asset owners can identify the impact or consequences of their damage, loss or destruction. This part of risk identification is commonly referred to as impact assessment.

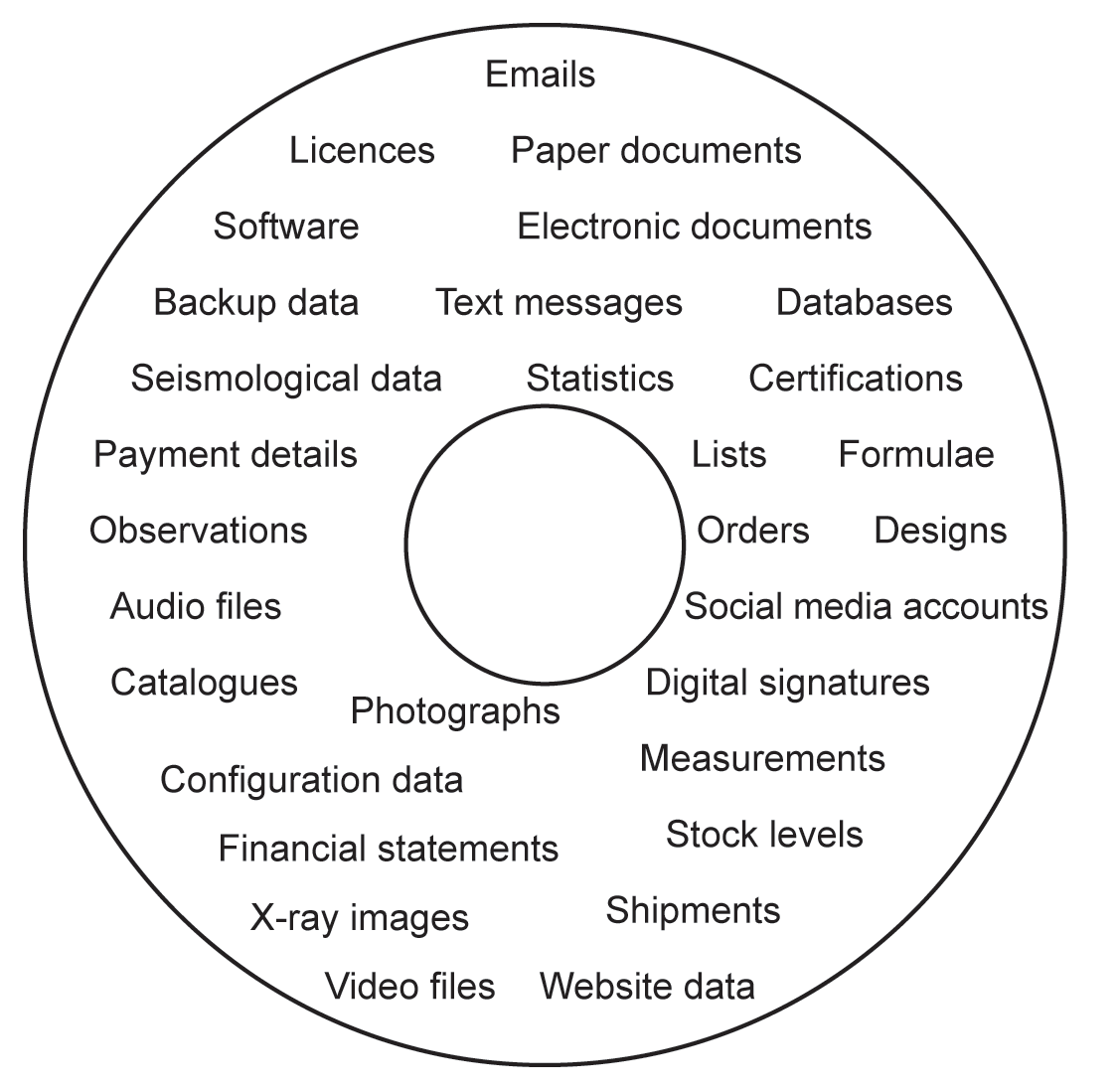

Let us take a look firstly at the types of information we might identify. Mostly, these days, we think of information being in electronic form, but it is important to remember other information that remains in the form of paper documents, microfiche, microfilm and so on. Also, while much of the information we are concerned with will be alphanumeric in nature, there may be other types that are critical to the organisation, such as software, audio and video files, photographs or ‘raw’ data, such as that recorded from seismographic surveys and weather observations. Figure 4.2 illustrates many types of information, but individual organisations will doubtless identify others that are peculiar to their sector or business type, and which must also be considered.

The main factor that will help to identify those information assets that must be within the scope of the programme is a list of business-critical activities. However, even though this will identify many of the organisation’s information assets, the business-critical activities themselves should be subjected to some form of analysis to take into account other non-critical activities upon which the business-critical activities have a greater or lesser degree of dependence.

For most organisations, the main areas of information assets may include:

- Operational information that underpins the very nature of the organisation, such as customer order history, stock control or product designs.

- Personal information, as defined within data protection legislation such as names, postal and email addresses and telephone numbers.

- Strategic information, such as sales forecasts, development schedules or product launch plans.

- Information that is expensive to collect, store or process, such as census information.

It is unlikely that information that falls outside these categories will be critical to an organisation’s performance, and it may be omitted from the information identification scope with the agreement of the relevant information owners, and should be recorded as such.

THE APPROACH TO RISK IDENTIFICATION

There are several different skills required in order to conduct a successful impact assessment. These are described in greater detail in Chapter 9 – Communication, Consultation, Monitoring and Review.

It may be the case that no individual within the organisation possesses all these skills, in which case the combined skills of two (or possibly more) people may be employed. In any event, it is always advantageous to have a second opinion when undertaking this kind of activity, and another pair of eyes and ears can pick up things that an individual might overlook.

An effective method for commencing an impact assessment is to hold an introductory workshop to inform and engage the senior management team, who will then be best positioned to brief their departmental managers and staff on what to expect and what to research. Beyond that, the approach taken for interviews will need to be tailored to the type of audience.

Some interviews are best conducted on a one-to-one basis, especially if there are sensitive issues at stake, whereas others may benefit from a group discussion or workshop in order to ensure that the views of different sections within a department are considered.

Telephone interviews should be avoided where possible unless there is no alternative, as the visual signals given in face-to-face meetings can provide additional clues; however, video conferencing calls such as Zoom, FaceTime, Skype and Webex may well be an acceptable alternative. Follow-up telephone discussions to review the findings present less of a problem.

At all times, the interviewer should give the interviewee time to reflect on the question and, once an answer has been recorded, it is worth the interviewer summarising the discussion as a quick means of verifying the findings. It is also important to choose the order of questions carefully. Questioning should follow a logical sequence – for example, the same sequence as a development or production process in which information is used and generated – in order to permit the interviewee to follow a more logical thought process when answering.

At the beginning of the risk identification process, the most appropriate format of the impact analysis should be agreed with the programme sponsor, although flexibility is always important and it may be necessary to modify the format as the interviews progress and findings are recorded.

EVENTS OR INCIDENTS?

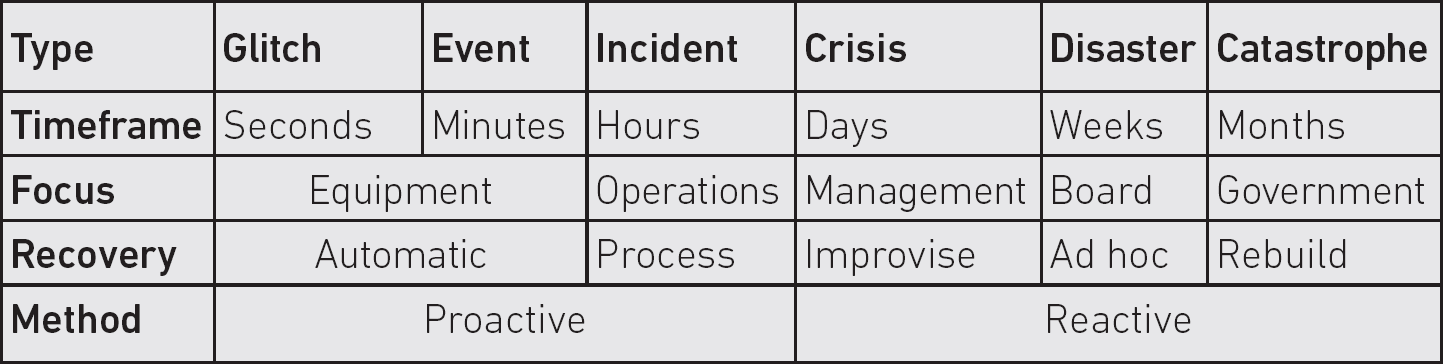

For the purposes of this book, we shall refer to events and incidents as having the same characteristics, since both terms are frequently used interchangeably to discuss something detrimental that has occurred. However, it is worth taking a very brief look at how the incident management (IM) – especially the BC management – communities view the terms. A general view is illustrated in Table 4.1.

Table 4.1 The general properties of detrimental situations

Glitches

Extremely short occurrences are often referred to as glitches. They usually last a few seconds at the most and generally refer to brief interruptions in power, computer processing, television and radio transmissions. Activities usually return to normal following most glitches as equipment self-corrects automatically.

Events

Events normally last no more than a few minutes. Like glitches, the equipment they affect is frequently automatically self-correcting, but may on occasion require a degree of manual intervention.

Incidents are viewed as lasting no more than a few hours. Unlike glitches and events, they usually require operational resolution, normally requiring manual intervention that follows some form of process.

The methods of dealing with glitches, events and incidents are all proactive in nature.

Crises

Crises generally last for at least several days. Although organisations may have plans, processes and procedures to deal with them, and although operational staff will carry out any remedial actions, some degree of improvisation may be required. Crises almost invariably require a higher layer of management to take control of the situation, make decisions and communicate with senior management and the media.

Disasters

Disasters generally last for weeks. As with crises, operational staff will carry out remedial actions, although at this stage a degree of ad hoc action may be necessary, and, even if a higher management layer will control activities, the senior management layer will take overall charge of the situation.

Catastrophes

Catastrophes are the most serious level, often lasting for months, or in some cases for years. Their scale tends to affect many communities, and so, although individual organisations may be operating their own recovery plans, it is likely that local, regional or even national government will oversee the situation and that a complete rebuilding of the infrastructure may be required.

Despite any proactive planning or activities to lessen their impact or likelihood, crises, disasters and catastrophes all require reactive activities.

Incidents, crises, disasters and catastrophes generally follow a set sequence of planning, preparation and testing, incident response, business continuity operations and resumption to normal operations, as shown in Figure 4.3.

Figure 4.3 Generic sequence of situation management

The next real piece of work in risk assessment is that of identifying the impacts or consequences to the information assets.

Let us begin by understanding what actually comprises impact or consequence. In general terms, an impact is the adverse result of some action (a threat or hazard), taking advantage of a weakness or vulnerability in an information asset, as shown in Figure 4.4.

Figure 4.4 A simple threat, vulnerability and impact

However, the situation is not always as simple as this, since there can be more than one threat against an information asset that takes advantage of the same vulnerability and results in the same impact, as shown in Figure 4.5.

Figure 4.5 Multiple threats can exploit the same vulnerability

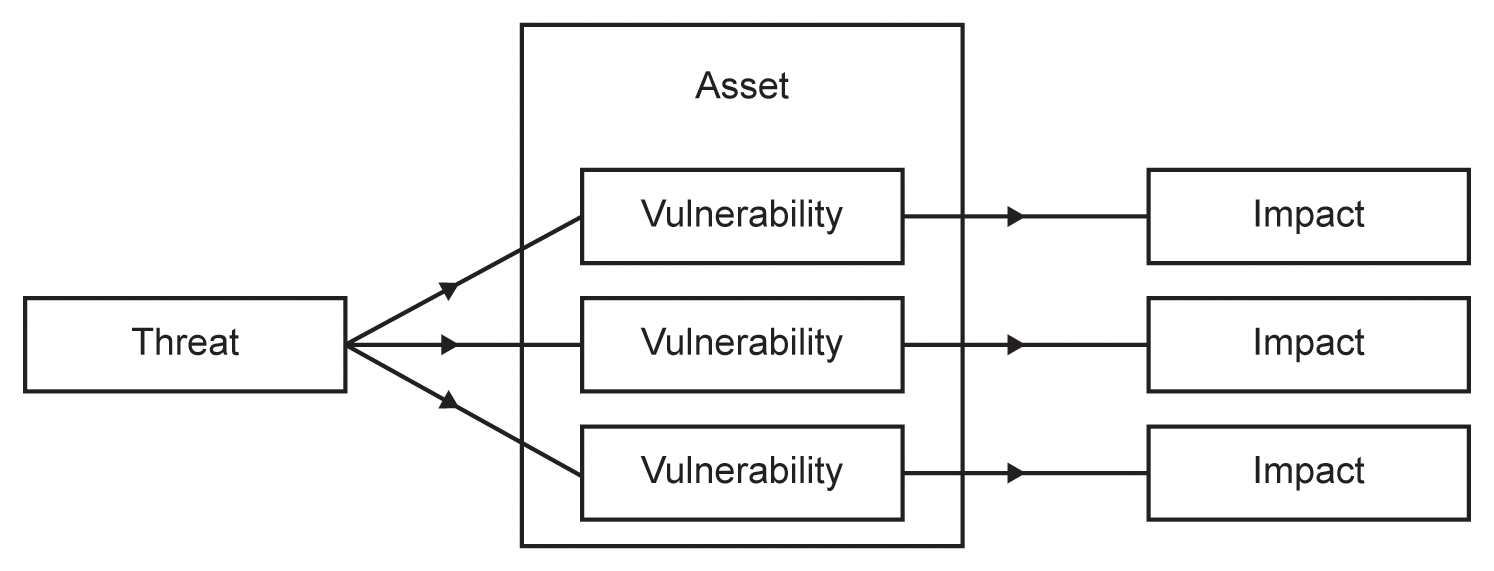

Also, of course, it is quite possible that an information asset exhibits a number of vulnerabilities and that a single threat attacks each, resulting in a number of different impacts, as depicted in Figure 4.6.

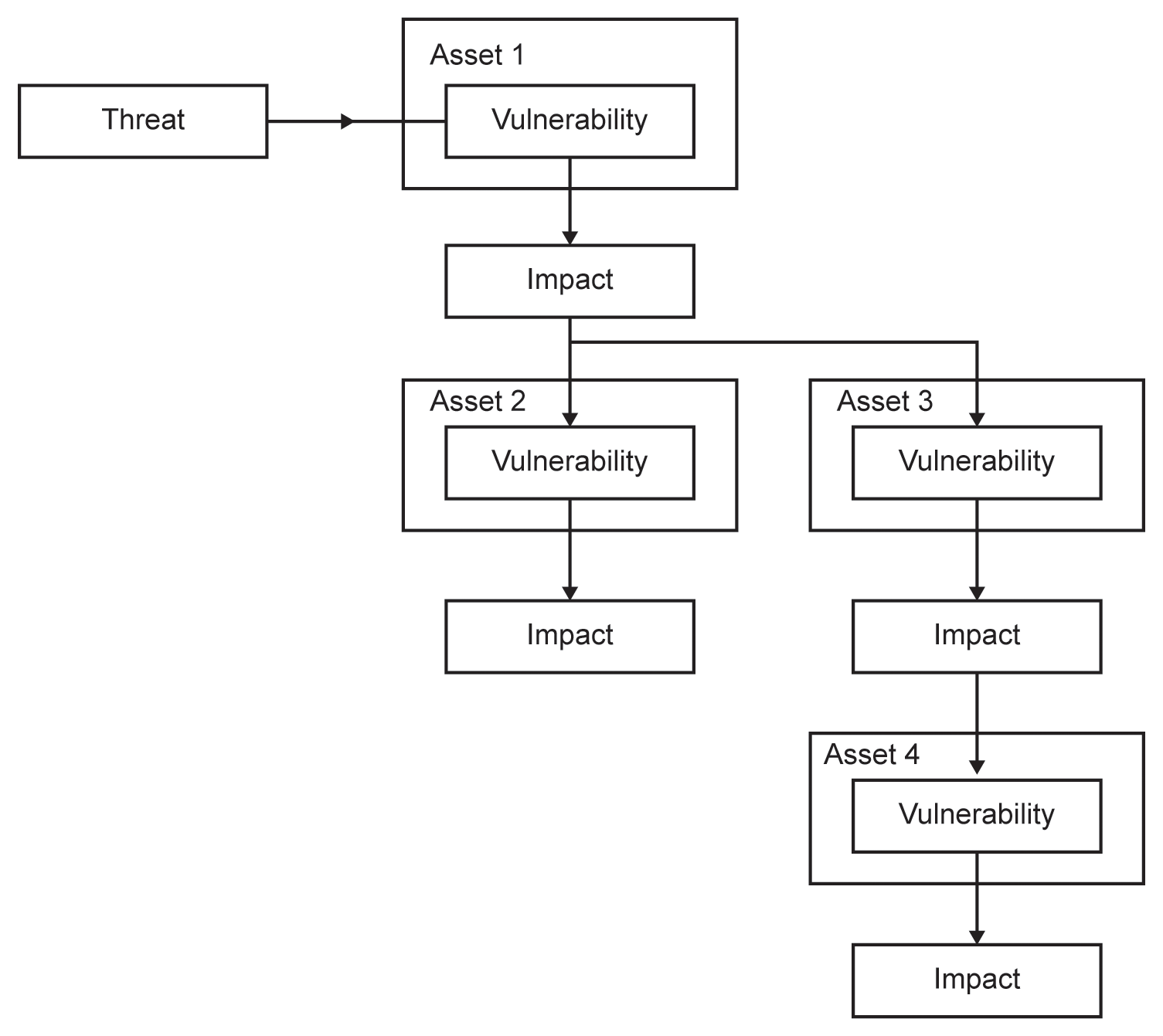

Finally, there is the so-called ‘knock-on effect’ or ‘chain of consequence’, in which a threat exploits a vulnerability in one information asset, and the resulting impact becomes a threat to another information asset, and so on. These chains of consequence can be quite complicated to follow, but whenever impact assessments are carried out, it should be borne in mind that such a chain may well exist, and where the assessor can imagine links of dependencies between information assets, the possibility of such a chain should be consciously explored.

Figure 4.7 illustrates such a chain of consequence. A threat exploits a vulnerability in asset 1, resulting in an impact that has a knock-on effect to become the threat facing assets 2 and 3, and in turn the impact on asset 3 becomes the threat that affects asset 4.

Figure 4.7 A typical chain of consequence

An excellent example of chains of consequence is the failure in a fully automated environment of an organisation’s order processing system. Without the output from this, the organisation’s production line would not be able to produce the order, the despatch department would have nothing to deliver and the billing department would be unable to produce an invoice.

When examining chains of consequence, it is important that progress through the chain is traced back to its root cause – sometimes referred to as ‘root cause analysis’, since it is the root cause that triggers all the subsequent impacts.

Types of impact

Before we examine the various types of impact, we need to understand that they will affect the organisation in slightly different ways, depending on their origin. On the first level, there are two categories:

Primary or immediate impacts. These result from the event itself, when a business function is detrimentally affected or unable to continue. They come in two varieties:

- Direct primary impacts – for example, if a customer database is hacked and personal information is stolen, the organisation will lose control of that valuable information resource.

- Indirect primary impacts – these may occur as a consequence of the direct impact. In the above example, the Information Commissioner might levy a fine against the organisation for failing to adequately protect the information.

Secondary or future impacts are those that result from responding to or recovering from the event.

- Direct secondary impacts include such things as customers purchasing their products or services from another supplier.

- Indirect secondary impacts include such things as fines imposed for failing to file statutory returns on time because the necessary information is unavailable.

Figure 4.8 takes the ‘simple’ impact model described above, and breaks it down further.

Figure 4.8 Impact types

For the purposes of this book, we have organised impacts into five types, and we shall examine each in greater detail:

- operational impacts;

- financial impacts;

- legal and regulatory impacts;

- reputational impacts;

- wellbeing of staff and the public-at-large impacts.

Operational impacts

As the name suggests, operational impacts are those that impair the day-to-day activities of the organisation. Very often, direct operational impacts will result in subsequent indirect financial impacts, so an inability to meet a service contract may well result in lost orders or claims for contractual damages. These include (but are not limited to):

- the loss of or damage to the confidentiality, integrity or availability of information;

- the loss of or damage to premises and equipment;

- order backlogs;

- productivity losses;

- industrial action;

- reduced competitive capability;

- the organisation’s inability to meet service contracts;

- the organisation’s inability to progress new business or developments;

- damage to third-party relations;

- impaired management control;

- the loss of customers to competitors, known in some sectors as ‘churn’.

Most operational impacts are felt by the organisation very quickly – their presence will usually be very obvious, and not only within the organisation itself, but also to the public-at-large and the media. Because of this, operational impacts are frequently dealt with in a reactive way by invoking some form of IM process to bring the situation under control, to recover from the incident and eventually to return to normal. IM is more usually associated with BC, but very much has a place in information risk management as well.

Financial impacts

Unsurprisingly, financial impacts or consequences are normally those that gain the greatest attention within the organisation. It is frequently against a backdrop of possible financial loss that the costs of remedial actions will be compared. While this is certainly correct, it is also true for other types of impact as well:

- loss of current and future business opportunities;

- increased cost of borrowing;

- cancellation of contracts;

- contractual penalties;

- loss of cash flow;

- replacement and redevelopment costs;

- loss of share price;

- increased insurance premiums;

- loss of tangible assets.

Many of these impacts – for example, lost sales immediately following the event – will be felt very quickly, while others – for example, increased insurance premiums – may not manifest themselves until a later date, possibly some considerable time after the costs of the event have been counted.

Financial impacts may also not be as noticeable to the whole organisation – for example, staff may not be aware of the financial implications of an event at all, and have no appreciation of the position in which the organisation finds itself until they read about it in the media or find that pay increases and bonuses are reduced.

Legal and regulatory impacts

As with reputational impacts, legal and regulatory impacts can have serious repercussions on an organisation, and the handling of these is best dealt with by a specialist team within the organisation – who may communicate information regarding an event through the corporate communication department. Legal and regulatory impacts, which can also be referred to as consequential losses, include:

- warnings or penalties from sector regulators;

- fines for late submission of company accounts;

- fines for late payment of taxes;

- breach of contract damages;

- penalties for fraud and other criminal acts.

Reputational impacts

Reputational impacts are almost always highly detrimental to the organisation. For this reason, many organisations employ communication specialists who are skilled in countering negative publicity and putting a positive spin on any bad news. In such organisations, most staff are advised not to talk directly to the media, but to pass enquiries through to the corporate communication department.

Reputational impacts, which can also be referred to as consequential losses, include:

- stock market confidence;

- competitors taking advantage;

- customer perception;

- public perception;

- industry and institutional image;

- confidential information made public.

The reputation of an organisation can be destroyed overnight. Take the case of the Gerald Ratner chain of cut-price jewellery shops in the 1990s. Ratner made a speech at the Institute of Directors during which he made several derogatory remarks about the products he sold. Despite the fact that he had thought the remarks were ‘off the cuff’, they were reported in the press and customers exacted their revenge by staying away. The value of the organisation plummeted by around £500 million, and the company very nearly ceased trading.

Wellbeing of staff and the public-at-large impacts

Although more rare, safety incidents are generally highly visible outside the organisation, and occasionally have an impact on the public. More common, however, are any events that may have an adverse effect on the organisation’s staff, and these can also cascade into financial and operational secondary impacts. Wellbeing impacts include:

- safety, health risks and injuries;

- stress and trauma;

- low morale of staff.

Qualitative and quantitative assessments

Qualitative assessments are almost always subjective. The terms ‘low’, ‘medium’ and ‘high’ give a general indication of the level of impact, but do not tell us how much. Quantitative assessments, on the other hand, can be very specific, and rather more accurate. The main problem with quantitative assessments is that, if they are to be entirely useful, they can take a great deal of time to undertake, and mostly total accuracy is not a requirement.

In the case of impact assessment, it may be worthwhile taking an initial qualitative pass in order to give an idea of the levels of risk and to identify those risks that are likely to be severe, with the objective of a more qualitative assessment later on.

Alternatively, a compromise solution often works well, since it can combine objective detail with subjective description. Instead of spending significant amounts of time in establishing the exact losses that might be incurred by a particular activity, the compromise solution takes a range of impact values and assigns descriptive terms to them. This is also known as semi-quantitative assessment.

So, for example, we might state that in a particular scenario, the term ‘very low’ approximates to values up to £25,000, ‘low’ to values between £25,000 and £250,000, ‘medium’ to values between £250,000 and £1 million; ‘high’ to values between £1 million and £25 million; and ‘very high’ to values in excess of £25 million. Although we have provided boundaries for the levels, there will be a degree of uncertainty about the upper and lower limits of each, but in general the ranges should be sufficient to provide a reasonable assessment, placing it in terms that the board will understand quickly. Clearly, these ranges will differ from one scenario to another, but set a common frame of reference when there are a substantial number of assessments to be carried out. These ranges should be agreed when setting the criteria for assessment.

For those situations in which there are no applicable financial values, such as reputational or operational impacts, a similar method of quantification can be used. Table 4.2 illustrates some possible options.

Table 4.2 Typical impact scales

Impact assessment questions

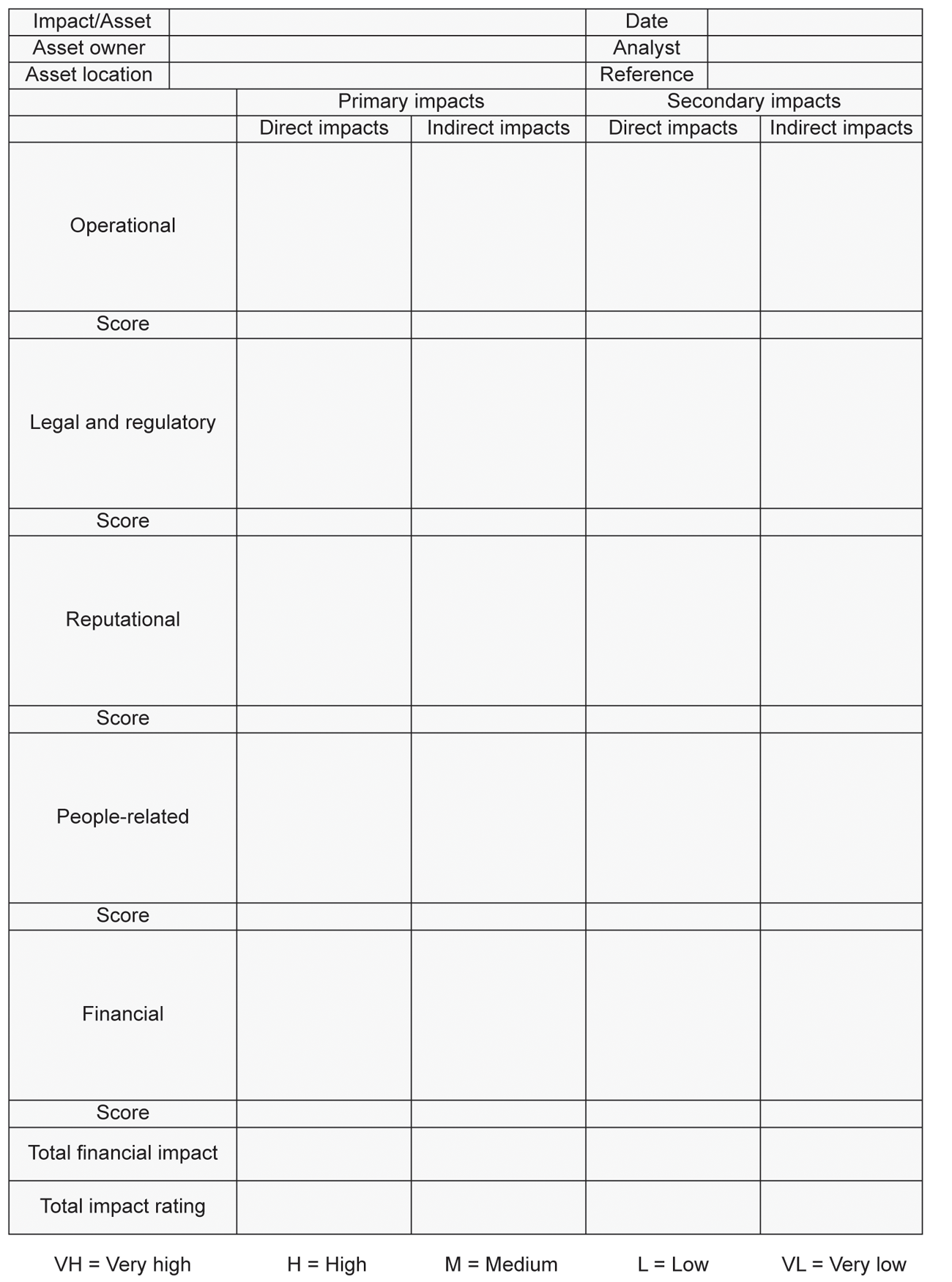

Let’s take a look at the questions we need to ask when conducting an impact assessment. Note that a suggested template form for this is included in Appendix F.

To begin with, apart from basic information such as name of department, name of contact(s) and contact details, for each information asset we will need to understand:

- The capital value of the asset if it has one.

- The current and projected revenues the asset generates or contributes to.

- The value of any resources and activities required to maintain and support this asset, including:

- staff;

- systems hardware;

- systems operating system and application software;

- information such as databases, designs, etc.;

- services, including third-party services;

- premises;

- other infrastructure.

- The required operational levels for each of these resources, in the short, medium and long terms.

- How long the organisation can survive without these resources, expressed in minutes, hours, days or weeks (note that in BC terms, this is often referred to as the maximum tolerable period of disruption, or MTPD).

- The impact on the information asset in terms of operational, financial, legal and regulatory, reputational and people impact.

- How long any relevant activities take to complete.

- What effect disruptions have on these activities and other activities within the business.

- What dependencies there are for activities to be completed.

Who should be involved in an impact assessment?

Clearly, the information asset owner should be the first port of call for this activity. However, although the information asset owner may be familiar with the technical details of the asset itself, he or she may not be able to express its value in business terms, so it is always worth double-checking with another person – or group of people in the case of substantial information assets such as a customer database, which may cut across several different areas of the organisation.

In larger organisations, it is quite possible that impact assessments may be carried out at three different levels, with the senior management team defining what information assets are critical to the organisation at a strategic level, departmental managers refining this assessment and identifying the individual components, and operational managers making the final impact assessments themselves.

Strategic impact assessment

The strategic impact assessment begins with input from senior management who have a detailed high-level view of the organisation. They will be able to interpret the organisation’s position in terms of both the internal and external contexts, and will appreciate the value of the customer base and the organisation’s overall information assets.

The strategic impact assessment will determine which information assets are deemed to be essential to the survival of the organisation, and will make an initial estimate of the importance of each. This may well be modified in the tactical impact assessment when details of the information assets become clearer. If the organisation decides to omit any information assets from the impact assessment, the reasoning behind this decision should be clearly stated.

The strategic impact assessment should take into account the business-specific factors or general impact types that might affect the organisation, such as the interests of stakeholders, any statutory, legal or regulatory obligations, the reputation of the organisation and its financial future. The organisation must begin by clearly defining at what point the level of impact constitutes a change from ‘tolerable’ to ‘intolerable’.

When conducting a strategic impact assessment, each information asset should be separately investigated against each general impact type, and estimation made of the likely time that might elapse before it becomes business-affecting, since loss of information assets may not be felt immediately. It is also useful at this stage to provide any reasoning for this, so a more objective analysis can be conducted, especially in cases where two or more information assets are considered, and the organisation feels it is desirable to prioritise one over the other.

Tactical impact assessment

Senior managers will undoubtedly have a general idea of what information assets are critical to the organisation, but may not have a detailed knowledge of their makeup, or who is responsible for them, so, having agreed which information assets are being covered by the strategic impact assessment, we now turn to the tactical impact assessment and set the scope of this work.

In this case, we are less interested in the external context as this will already have been addressed by the strategic business impact assessment, but we are now interested in those of the organisation’s activities that contribute to the delivery of the organisation’s products and services and any interdependencies between them. It may be extremely useful to piece together a block diagram or process flow diagram illustrating these interdependencies in order to simplify later work.

Operational impact assessment

Finally, we turn to the operational level of impact assessment, in which those managers having a detailed knowledge of and responsibility for the information asset provide an assessment of the actual potential impact of the asset’s damage, loss or destruction.

Over- and underestimation

When carrying out impact and likelihood assessments, a mistake frequently made is either to over- or underestimate the realities of the situation. Often this is done with the best of intentions, but either of these can cause considerable difficulties later in the risk management process.

If over-estimation takes place, more time, effort and money might be spent in treating risks than is necessary, or indeed the balance between the potential losses and the costs of treatment may change to make the correct form of risk treatment uneconomical.

Where underestimation occurs, risks that should be viewed as being more serious might well not be treated to a sufficient extent, or may be unwittingly accepted when avoidance, transfer or reduction might have been a more appropriate option.

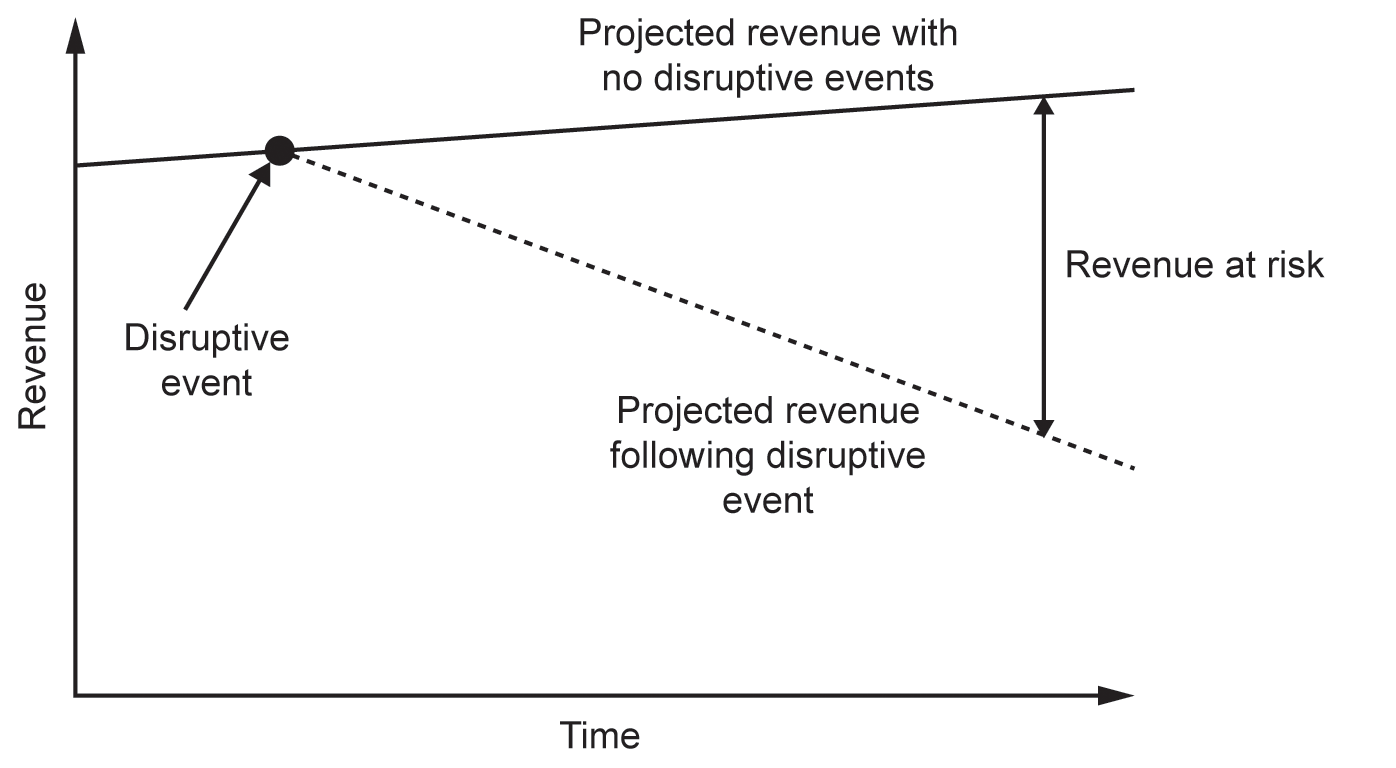

Time dependency

Impacts can also change with and over time. Those threats that affect capital items – buildings, equipment and so on – will almost certainly result in an instantaneous financial impact, while those that affect sales revenue streams, for example, will possibly show little impact at first, but over the course of days or weeks the impact would increase in a more or less linear fashion. The other factor affecting this form of impact will be the hours during which the information must be available, since a systems failure that occurs ‘out of hours’ may have no effect on revenue at all, but will invariably cause considerable disruption when business resumes on the next working day.

Figure 4.9 illustrates how the organisation might view the impact of financial losses over time.

Figure 4.9 Potential losses over time following a disruptive event

There are, of course, some times that are the worst possible for an incident to affect information assets. These include:

- regular events, such as end-of-month accounting dates;

- seasonal occasions, such as Easter, Christmas and summer holidays;

- heavy load occasions, such as the beginning of the school or university year.

Once the interviews or workshops have been completed, and the results of the questionnaires have been recorded, they should be passed back to the originators for review and comment. The originators should be allowed time to consider their input and invited to verify the accuracy of the information before it is finalised for presentation. A typical impact assessment form might look something like that shown in Figure 4.10.

Figure 4.10 Typical impact assessment form

In this chapter, we have examined the approach to identifying the risks to our information assets, seen how an impact assessment can be conducted and looked at a number of different types of impact, together with understanding the differences between qualitative and quantitative assessments.

The next stage of the information risk management programme is to understand the threats the organisation faces to its information assets, and the vulnerabilities that these may exhibit.