After studying this chapter, you should be able to:

Up to this point, you have learned the basic guidelines that corporations use to report information to investors and creditors. Corporations also must file income tax returns following the guidelines developed by the Internal Revenue Service (IRS). Because GAAP and tax regulations differ in a number of ways, so frequently do pretax financial income and taxable income. Consequently, the amount that a company reports as tax expense will differ from the amount of taxes payable to the IRS. Illustration 19-1 highlights these differences.

Pretax financial income is a financial reporting term. It also is often referred to as income before taxes, income for financial reporting purposes, or income for book purposes. Companies determine pretax financial income according to GAAP. They measure it with the objective of providing useful information to investors and creditors.

Taxable income (income for tax purposes) is a tax accounting term. It indicates the amount used to compute income tax payable. Companies determine taxable income according to the Internal Revenue Code (the tax code). Income taxes provide money to support government operations.

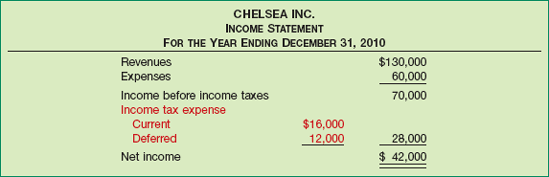

To illustrate how differences in GAAP and IRS rules affect financial reporting and taxable income, assume that Chelsea Inc. reported revenues of $130,000 and expenses of $60,000 in each of its first three years of operations. Illustration 19-2 shows the (partial) income statement over these three years.

For tax purposes (following the tax code), Chelsea reported the same expenses to the IRS in each of the years. But, as Illustration 19-3 shows, Chelsea reported taxable revenues of $100,000 in 2010, $150,000 in 2011, and $140,000 in 2012.

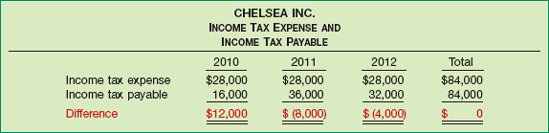

Income tax expense and income tax payable differed over the three years, but were equal in total, as Illustration 19-4 shows.

The differences between income tax expense and income tax payable in this example arise for a simple reason. For financial reporting, companies use the full accrual method to report revenues. For tax purposes, they use a modified cash basis. As a result, Chelsea reports pretax financial income of $70,000 and income tax expense of $28,000 for each of the three years. However, taxable income fluctuates. For example, in 2010 taxable income is only $40,000, so Chelsea owes just $16,000 to the IRS that year. Chelsea classifies the income tax payable as a current liability on the balance sheet.

As Illustration 19-4 indicates, for Chelsea the $12,000 ($28,000 − $16,000) difference between income tax expense and income tax payable in 2010 reflects taxes that it will pay in future periods. This $12,000 difference is often referred to as a deferred tax amount. In this case it is a deferred tax liability. In cases where taxes will be lower in the future, Chelsea records a deferred tax asset. We explain the measurement and accounting for deferred tax liabilities and assets in the following two sections.[339]

The example summarized in Illustration 19-4 shows how income tax payable can differ from income tax expense. This can happen when there are temporary differences between the amounts reported for tax purposes and those reported for book purposes. A temporary difference is the difference between the tax basis of an asset or liability and its reported (carrying or book) amount in the financial statements, which will result in taxable amounts or deductible amounts in future years. Taxable amounts increase taxable income in future years. Deductible amounts decrease taxable income in future years.

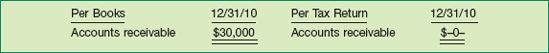

In Chelsea's situation, the only difference between the book basis and tax basis of the assets and liabilities relates to accounts receivable that arose from revenue recognized for book purposes. Illustration 19-5 indicates that Chelsea reports accounts receivable at $30,000 in the December 31, 2010, GAAP-basis balance sheet. However, the receivables have a zero tax basis.

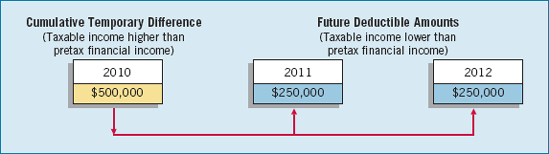

What will happen to the $30,000 temporary difference that originated in 2010 for Chelsea? Assuming that Chelsea expects to collect $20,000 of the receivables in 2011 and $10,000 in 2012, this collection results in future taxable amounts of $20,000 in 2011 and $10,000 in 2012. These future taxable amounts will cause taxable income to exceed pretax financial income in both 2011 and 2012.

An assumption inherent in a company's GAAP balance sheet is that companies recover and settle the assets and liabilities at their reported amounts (carrying amounts). This assumption creates a requirement under accrual accounting to recognize currently the deferred tax consequences of temporary differences. That is, companies recognize the amount of income taxes that are payable (or refundable) when they recover and settle the reported amounts of the assets and liabilities, respectively. Illustration 19-6 shows the reversal of the temporary difference described in Illustration 19-5 and the resulting taxable amounts in future periods.

Chelsea assumes that it will collect the accounts receivable and report the $30,000 collection as taxable revenues in future tax returns. A payment of income tax in both 2011 and 2012 will occur. Chelsea should therefore record in its books in 2010 the deferred tax consequences of the revenue and related receivables reflected in the 2010 financial statements. Chelsea does this by recording a deferred tax liability.

A deferred tax liability is the deferred tax consequences attributable to taxable temporary differences. In other words, a deferred tax liability represents the increase in taxes payable in future years as a result of taxable temporary differences existing at the end of the current year.

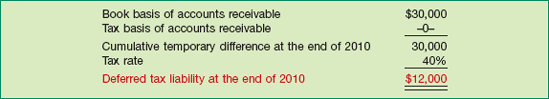

Recall from the Chelsea example that income tax payable is $16,000 ($40,000 × 40%) in 2010 (Illustration 19-4 on page 993). In addition, a temporary difference exists at year-end because Chelsea reports the revenue and related accounts receivable differently for book and tax purposes. The book basis of accounts receivable is $30,000, and the tax basis is zero. Thus, the total deferred tax liability at the end of 2010 is $12,000, computed as shown in Illustration 19-7 (on page 995).

Companies may also compute the deferred tax liability by preparing a schedule that indicates the future taxable amounts due to existing temporary differences. Such a schedule, as shown in Illustration 19-8, is particularly useful when the computations become more complex.

Because it is the first year of operations for Chelsea, there is no deferred tax liability at the beginning of the year. Chelsea computes the income tax expense for 2010 as shown in Illustration 19-9.

This computation indicates that income tax expense has two components—current tax expense (the amount of income tax payable for the period) and deferred tax expense. Deferred tax expense is the increase in the deferred tax liability balance from the beginning to the end of the accounting period.

Companies credit taxes due and payable to Income Tax Payable, and credit the increase in deferred taxes to Deferred Tax Liability. They then debit the sum of those two items to Income Tax Expense. For Chelsea, it makes the following entry at the end of 2010.

At the end of 2011 (the second year), the difference between the book basis and the tax basis of the accounts receivable is $10,000. Chelsea multiplies this difference by the applicable tax rate to arrive at the deferred tax liability of $4,000 ($10,000 × 40%), which it reports at the end of 2011. Income tax payable for 2011 is $36,000 (Illustration 19-3 on page 993), and the income tax expense for 2011 is as shown in Illustration 19-10.

Chelsea records income tax expense, the change in the deferred tax liability, and income tax payable for 2011 as follows.

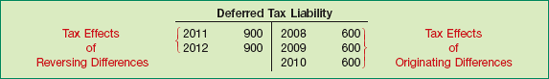

The entry to record income taxes at the end of 2012 reduces the Deferred Tax Liability by $4,000. The Deferred Tax Liability account appears as follows at the end of 2012.

The Deferred Tax Liability account has a zero balance at the end of 2012.

Some analysts dismiss deferred tax liabilities when assessing the financial strength of a company. But the FASB indicates that the deferred tax liability meets the definition of a liability established in Statement of Financial Accounting Concepts No. 6, "Elements of Financial Statements" because:

It results from a past transaction. In the Chelsea example, the company performed services for customers and recognized revenue in 2010 for financial reporting purposes but deferred it for tax purposes.

It is a present obligation. Taxable income in future periods will exceed pretax financial income as a result of this temporary difference. Thus, a present obligation exists.

It represents a future sacrifice. Taxable income and taxes due in future periods will result from past events. The payment of these taxes when they come due is the future sacrifice.

A study by B. Ayers indicates that the market views deferred tax assets and liabilities similarly to other assets and liabilities. Further, the study concludes that the FASB rules in this area increased the usefulness of deferred tax amounts in financial statements.

Source: B. Ayers, "Deferred Tax Accounting Under SFAS No. 109: An Empirical Investigation of Its Incremental Value-Relevance Relative to APB No. 11," The Accounting Review (April 1998).

One objective of accounting for income taxes is to recognize the amount of taxes payable or refundable for the current year. In Chelsea's case, income tax payable is $16,000 for 2010.

A second objective is to recognize deferred tax liabilities and assets for the future tax consequences of events already recognized in the financial statements or tax returns. For example, Chelsea sold services to customers that resulted in accounts receivable of $30,000 in 2010. It reported that amount on the 2010 income statement, but not on the tax return as income. That amount will appear on future tax returns as income for the period when collected. As a result, a $30,000 temporary difference exists at the end of 2010, which will cause future taxable amounts. Chelsea reports a deferred tax liability of $12,000 on the balance sheet at the end of 2010, which represents the increase in taxes payable in future years ($8,000 in 2011 and $4,000 in 2012) as a result of a temporary difference existing at the end of the current year. The related deferred tax liability is reduced by $8,000 at the end of 2011 and by another $4,000 at the end of 2012.

In addition to affecting the balance sheet, deferred taxes impact income tax expense in each of the three years affected. In 2010, taxable income ($40,000) is less than pretax financial income ($70,000). Income tax payable for 2010 is therefore $16,000 (based on taxable income). Deferred tax expense of $12,000 results from the increase in the Deferred Tax Liability account on the balance sheet. Income tax expense is then $28,000 for 2010.

In 2011 and 2012, however, taxable income will exceed pretax financial income, due to the reversal of the temporary difference ($20,000 in 2011 and $10,000 in 2012). Income tax payable will therefore exceed income tax expense in 2011 and 2012. Chelsea will debit the Deferred Tax Liability account for $8,000 in 2011 and $4,000 in 2012. It records credits for these amounts in Income Tax Expense. These credits are often referred to as a deferred tax benefit (which we discuss again later on).

Assume that during 2010, Cunningham Inc. estimated its warranty costs related to the sale of microwave ovens to be $500,000, paid evenly over the next two years. For book purposes, in 2010 Cunningham reported warranty expense and a related estimated liability for warranties of $500,000 in its financial statements. For tax purposes, the warranty tax deduction is not allowed until paid. Therefore, Cunningham recognizes no warranty liability on a tax-basis balance sheet. Illustration 19-12 shows the balance sheet difference at the end of 2010.

When Cunningham pays the warranty liability, it reports an expense (deductible amount) for tax purposes. Because of this temporary difference, Cunningham should recognize in 2010 the tax benefits (positive tax consequences) for the tax deductions that will result from the future settlement of the liability. Cunningham reports this future tax benefit in the December 31, 2010, balance sheet as a deferred tax asset.

We can think about this situation another way. Deductible amounts occur in future tax returns. These future deductible amounts cause taxable income to be less than pretax financial income in the future as a result of an existing temporary difference. Cunningham's temporary difference originates (arises) in one period (2010) and reverses over two periods (2011 and 2012). Illustration 19-13 diagrams this situation.

A deferred tax asset is the deferred tax consequence attributable to deductible temporary differences. In other words, a deferred tax asset represents the increase in taxes refundable (or saved) in future years as a result of deductible temporary differences existing at the end of the current year.

To illustrate, assume that Hunt Co. accrues a loss and a related liability of $50,000 in 2010 for financial reporting purposes because of pending litigation. Hunt cannot deduct this amount for tax purposes until the period it pays the liability, expected in 2011. As a result, a deductible amount will occur in 2011 when Hunt settles the liability (Estimated Litigation Liability), causing taxable income to be lower than pretax financial income. Illustration 19-14 (on page 998) shows the computation of the deferred tax asset at the end of 2010 (assuming a 40 percent tax rate).

Hunt can also compute the deferred tax asset by preparing a schedule that indicates the future deductible amounts due to deductible temporary differences. Illustration 19-15 shows this schedule.

Assuming that 2010 is Hunt's first year of operations, and income tax payable is $100,000, Hunt computes its income tax expense as follows.

The deferred tax benefit results from the increase in the deferred tax asset from the beginning to the end of the accounting period (similar to the Chelsea example earlier). The deferred tax benefit is a negative component of income tax expense. The total income tax expense of $80,000 on the income statement for 2010 thus consists of two elements—current tax expense of $100,000 and a deferred tax benefit of $20,000. For Hunt, it makes the following journal entry at the end of 2010 to record income tax expense, deferred income taxes, and income tax payable.

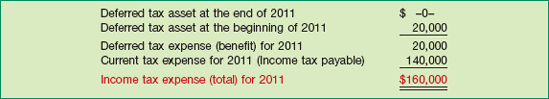

At the end of 2011 (the second year), the difference between the book value and the tax basis of the litigation liability is zero. Therefore, there is no deferred tax asset at this date. Assuming that income tax payable for 2011 is $140,000, Hunt computes income tax expense for 2011 as shown in Illustration 19-17.

The company records income taxes for 2011 as follows.

The total income tax expense of $160,000 on the income statement for 2011 thus consists of two elements—current tax expense of $140,000 and deferred tax expense of $20,000. Illustration 19-18 shows the Deferred Tax Asset account at the end of 2011.

A key issue in accounting for income taxes is whether a company should recognize a deferred tax asset in the financial records. Based on the conceptual definition of an asset, a deferred tax asset meets the three main conditions for an item to be recognized as an asset:

It results from a past transaction. In the Hunt example, the accrual of the loss contingency is the past event that gives rise to a future deductible temporary difference.

It gives rise to a probable benefit in the future. Taxable income exceeds pretax financial income in the current year (2010). However, in the next year the exact opposite occurs. That is, taxable income is lower than pretax financial income. Because this deductible temporary difference reduces taxes payable in the future, a probable future benefit exists at the end of the current period.

The entity controls access to the benefits. Hunt can obtain the benefit of existing deductible temporary differences by reducing its taxes payable in the future. Hunt has the exclusive right to that benefit and can control others' access to it.

Market analysts' reactions to the write-off of deferred tax assets also supports their treatment as assets. When Bethlehem Steel reported a $1 billion charge in a recent year to write off a deferred tax asset, analysts believed that Bethlehem was signaling that it would not realize the future benefits of the tax deductions. Thus, Bethlehem should write down the asset like other assets.

Source: J. Weil and S. Liesman, "Stock Gurus Disregard Most Big Write-Offs But They Often Hold Vital Clues to Outlook," Wall Street Journal Online (December 31, 2001).

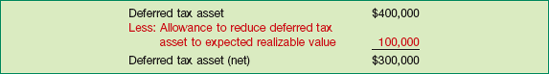

Companies recognize a deferred tax asset for all deductible temporary differences. However, based on available evidence, a company should reduce a deferred tax asset by a valuation allowance if it is more likely than not that it will not realize some portion or all of the deferred tax asset. "More likely than not" means a level of likelihood of at least slightly more than 50 percent.

Assume that Jensen Co. has a deductible temporary difference of $1,000,000 at the end of its first year of operations. Its tax rate is 40 percent, which means it records a deferred tax asset of $400,000 ($1,000,000 × 40%). Assuming $900,000 of income taxes payable, Jensen records income tax expense, the deferred tax asset, and income tax payable as follows.

After careful review of all available evidence, Jensen determines that it is more likely than not that it will not realize $100,000 of this deferred tax asset. Jensen records this reduction in asset value as follows.

This journal entry increases income tax expense in the current period because Jensen does not expect to realize a favorable tax benefit for a portion of the deductible temporary difference. Jensen simultaneously establishes a valuation allowance to recognize the reduction in the carrying amount of the deferred tax asset. This valuation account is a contra account. Jensen reports it on the financial statements in the following manner.

Jensen then evaluates this allowance account at the end of each accounting period. If, at the end of the next period, the deferred tax asset is still $400,000, but now it expects to realize $350,000 of this asset, Jensen makes the following entry to adjust the valuation account.

Jensen should consider all available evidence, both positive and negative, to determine whether, based on the weight of available evidence, it needs a valuation allowance. For example, if Jensen has been experiencing a series of loss years, it reasonably assumes that these losses will continue. Therefore, Jensen will lose the benefit of the future deductible amounts. We discuss the use of a valuation account under other conditions later in the chapter.

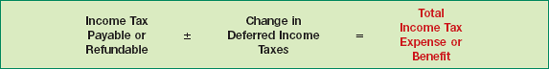

Circumstances dictate whether a company should add or subtract the change in deferred income taxes to or from income tax payable in computing income tax expense. For example, a company adds an increase in a deferred tax liability to income tax payable. On the other hand, it subtracts an increase in a deferred tax asset from income tax payable. The formula in Illustration 19-20 is used to compute income tax expense (benefit).

In the income statement or in the notes to the financial statements, a company should disclose the significant components of income tax expense attributable to continuing operations. Given the information related to Chelsea on page 993, Chelsea reports its income statement as follows.

As illustrated, Chelsea reports both the current portion (amount of income tax payable for the period) and the deferred portion of income tax expense. Another option is to simply report the total income tax expense on the income statement, and then indicate in the notes to the financial statements the current and deferred portions. Income tax expense is often referred to as "Provision for income taxes." Using this terminology, the current provision is $16,000, and the provision for deferred taxes is $12,000.

Numerous items create differences between pretax financial income and taxable income. For purposes of accounting recognition, these differences are of two types: (1) temporary, and (2) permanent.

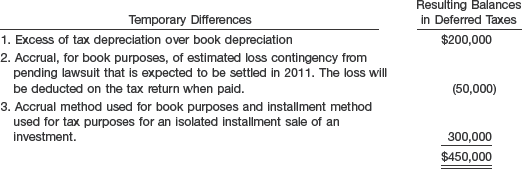

Taxable temporary differences are temporary differences that will result in taxable amounts in future years when the related assets are recovered. Deductible temporary differences are temporary differences that will result in deductible amounts in future years, when the related book liabilities are settled. Taxable temporary differences give rise to recording deferred tax liabilities. Deductible temporary differences give rise to recording deferred tax assets. Illustration 19-22 provides examples of temporary differences.

Determining a company's temporary differences may prove difficult. A company should prepare a balance sheet for tax purposes that it can compare with its GAAP balance sheet. Many of the differences between the two balance sheets are temporary differences.

Originating and Reversing Aspects of Temporary Differences. An originating temporary difference is the initial difference between the book basis and the tax basis of an asset or liability, regardless of whether the tax basis of the asset or liability exceeds or is exceeded by the book basis of the asset or liability. A reversing difference, on the other hand, occurs when eliminating a temporary difference that originated in prior periods and then removing the related tax effect from the deferred tax account.

For example, assume that Sharp Co. has tax depreciation in excess of book depreciation of $2,000 in 2008, 2009, and 2010. Further, it has an excess of book depreciation over tax depreciation of $3,000 in 2011 and 2012 for the same asset. Assuming a tax rate of 30 percent for all years involved, the Deferred Tax Liability account reflects the following.

The originating differences for Sharp in each of the first three years are $2,000. The related tax effect of each originating difference is $600. The reversing differences in 2011 and 2012 are each $3,000. The related tax effect of each is $900.

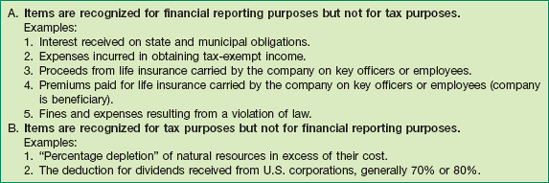

Some differences between taxable income and pretax financial income are permanent. Permanent differences result from items that (1) enter into pretax financial income but never into taxable income, or (2) enter into taxable income but never into pretax financial income.

Congress has enacted a variety of tax law provisions to attain certain political, economic, and social objectives. Some of these provisions exclude certain revenues from taxation, limit the deductibility of certain expenses, and permit the deduction of certain other expenses in excess of costs incurred. A corporation that has tax-free income, nondeductible expenses, or allowable deductions in excess of cost, has an effective tax rate that differs from its statutory (regular) tax rate.

Since permanent differences affect only the period in which they occur, they do not give rise to future taxable or deductible amounts. As a result, companies recognize no deferred tax consequences. Illustration 19-24 shows examples of permanent differences.

To illustrate the computations used when both temporary and permanent differences exist, assume that Bio-Tech Company reports pretax financial income of $200,000 in each of the years 2008, 2009, and 2010. The company is subject to a 30 percent tax rate, and has the following differences between pretax financial income and taxable income.

Bio-Tech reports an installment sale of $18,000 in 2008 for tax purposes over an 18-month period at a constant amount per month beginning January 1, 2009. It recognizes the entire sale for book purposes in 2008.

It pays life insurance premiums for its key officers of $5,000 in 2009 and 2010. Although not tax-deductible, Bio-Tech expenses the premiums for book purposes.

The installment sale is a temporary difference, whereas the life insurance premium is a permanent difference. Illustration 19-25 shows the reconciliation of Bio-Tech's pretax financial income to taxable income and the computation of income tax payable.

Note that Bio-Tech deducts the installment sales revenue from pretax financial income to arrive at taxable income. The reason: pretax financial income includes the installment sales revenue; taxable income does not. Conversely, it adds the $5,000 insurance premium to pretax financial income to arrive at taxable income. The reason: pretax financial income records an expense for this premium, but for tax purposes the premium is not deductible. As a result, pretax financial income is lower than taxable income. Therefore, the life insurance premium must be added back to pretax financial income to reconcile to taxable income.

Bio-Tech records income taxes for 2008, 2009, and 2010 as follows.

Bio-Tech has one temporary difference, which originates in 2008 and reverses in 2009 and 2010. It recognizes a deferred tax liability at the end of 2008 because the temporary difference causes future taxable amounts. As the temporary difference reverses, Bio-Tech reduces the deferred tax liability. There is no deferred tax amount associated with the difference caused by the nondeductible insurance expense because it is a permanent difference.

Although an enacted tax rate of 30 percent applies for all three years, the effective rate differs from the enacted rate in 2009 and 2010. Bio-Tech computes the effective tax rate by dividing total income tax expense for the period by pretax financial income. The effective rate is 30 percent for 2008 ($60,000 ÷ $200,000 = 30%) and 30.75 percent for 2009 and 2010 ($61,500 ÷ $200,000 = 30.75%).

In our previous illustrations, the enacted tax rate did not change from one year to the next. Thus, to compute the deferred income tax amount to report on the balance sheet, a company simply multiplies the cumulative temporary difference by the current tax rate. Using Bio-Tech as an example, it multiplies the cumulative temporary difference of $18,000 by the enacted tax rate, 30 percent in this case, to arrive at a deferred tax liability of $5,400 ($18,000 × 30%) at the end of 2008.

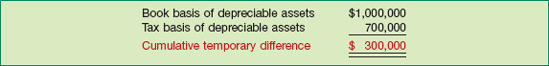

What happens if tax rates are expected to change in the future? In this case, a company should use the enacted tax rate expected to apply. Therefore, a company must consider presently enacted changes in the tax rate that become effective for a particular future year(s) when determining the tax rate to apply to existing temporary differences. For example, assume that Warlen Co. at the end of 2007 has the following cumulative temporary difference of $300,000, computed as shown in Illustration 19-26.

Furthermore, assume that the $300,000 will reverse and result in taxable amounts in the future, with the enacted tax rates shown in Illustration 19-27.

The total deferred tax liability at the end of 2007 is $108,000. Warlen may only use tax rates other than the current rate when the future tax rates have been enacted, as is the case in this example. If new rates are not yet enacted for future years, Warlen should use the current rate.

In determining the appropriate enacted tax rate for a given year, companies must use the average tax rate. The Internal Revenue Service and other taxing jurisdictions tax income on a graduated tax basis. For a U.S. corporation, the IRS taxes the first $50,000 of taxable income at 15 percent, the next $25,000 at 25 percent, with higher incremental levels of income at rates as high as 39 percent. In computing deferred income taxes, companies for which graduated tax rates are a significant factor must therefore determine the average tax rate and use that rate.

When a change in the tax rate is enacted, companies should record its effect on the existing deferred income tax accounts immediately. A company reports the effect as an adjustment to income tax expense in the period of the change.

Assume that on December 10, 2007, a new income tax act is signed into law that lowers the corporate tax rate from 40 percent to 35 percent, effective January 1, 2009. If Hostel Co. has one temporary difference at the beginning of 2007 related to $3 million of excess tax depreciation, then it has a Deferred Tax Liability account with a balance of $1,200,000 ($3,000,000 × 40%) at January 1, 2007. If taxable amounts related to this difference are scheduled to occur equally in 2008, 2009, and 2010, the deferred tax liability at the end of 2007 is $1,100,000, computed as follows.

Hostel, therefore, recognizes the decrease of $100,000 ($1,200,000 − $1,100,000) at the end of 2007 in the deferred tax liability as follows.

Corporate tax rates do not change often. Therefore, companies usually employ the current rate. However, state and foreign tax rates change more frequently, and they require adjustments in deferred income taxes accordingly.[340]

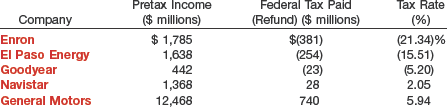

As mentioned in the opening story, companies employ various tax strategies to reduce their tax bills and their effective tax rates. The following table reports some high-profile cases in which profitable companies paid little income tax and, in some cases, got tax refunds.

These companies used various tools to lower their tax bills, including off-shore tax shelters, tax deferrals, and hefty use of stock options, the cost of which reduce taxable income but do not affect pretax financial income. Thus, companies can use various provisions in the tax code to reduce their effective tax rate well below the statutory rate of 35 percent.

One IRS provision designed to curb excessive tax avoidance is the alternative minimum tax (AMT). Companies compute their potential tax liability under the AMT, adjusting for various preference items that reduce their tax bills under the regular tax code. (Examples of such preference items are accelerated depreciation methods and the installment method for revenue recognition.) Companies must pay the higher of the two tax obligations computed under the AMT and the regular tax code. But, as indicated by the cases above, some profitable companies avoid high tax bills, even in the presence of the AMT. Indeed, a recent study by the Government Accounting Office found that roughly two-thirds of U.S. and foreign corporations paid no federal income taxes from 1998–2005. Many citizens and public-interest groups cite corporate avoidance of income taxes as a reason for more tax reform.

Source: H. Gleckman, D. Foust, M. Arndt, and K. Kerwin, "Tax Dodging: Enron Isn't Alone," Business Week (March 4, 2002), pp. 40–41; and L. Browning, "Study Tallies Corporations Not Paying Income Tax," New York Times (August 13, 2008), p. C3.

Every management hopes its company will be profitable. But hopes and profits may not materialize. For a start-up company, it is common to accumulate operating losses while expanding its customer base but before realizing economies of scale. For an established company, a major event such as a labor strike, rapidly changing regulatory and competitive forces, or a disaster such as 9/11 or Hurricane Ike can cause expenses to exceed revenues—a net operating loss.

A net operating loss (NOL) occurs for tax purposes in a year when tax-deductible expenses exceed taxable revenues. An inequitable tax burden would result if companies were taxed during profitable periods without receiving any tax relief during periods of net operating losses. Under certain circumstances, therefore, the federal tax laws permit taxpayers to use the losses of one year to offset the profits of other years.

Companies accomplish this income-averaging provision through the carryback and carryforward of net operating losses. Under this provision, a company pays no income taxes for a year in which it incurs a net operating loss. In addition, it may select one of the two options discussed below and on the following pages.

Through use of a loss carryback, a company may carry the net operating loss back two years and receive refunds for income taxes paid in those years. The company must apply the loss to the earlier year first and then to the second year. It may carry forward any loss remaining after the two-year carryback up to 20 years to offset future taxable income. Illustration 19-29 diagrams the loss carryback procedure, assuming a loss in 2010.

A company may forgo the loss carryback and use only the loss carryforward option, offsetting future taxable income for up to 20 years. Illustration 19-30 shows this approach.

Operating losses can be substantial. For example, Yahoo! had net operating losses of approximately $5.4 billion in a recent year. That amount translates into tax savings of $1.4 billion if Yahoo! is able to generate taxable income before the NOLs expire.

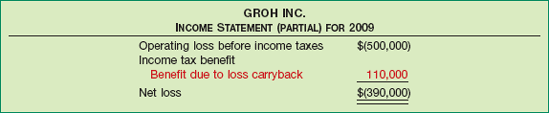

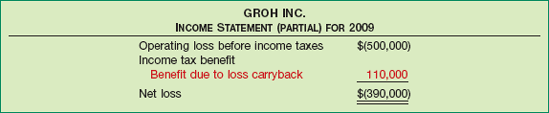

To illustrate the accounting procedures for a net operating loss carryback, assume that Groh Inc. has no temporary or permanent differences. Groh experiences the following.

In 2009, Groh incurs a net operating loss that it decides to carry back. Under the law, Groh must apply the carryback first to the second year preceding the loss year. Therefore, it carries the loss back first to 2007. Then, Groh carries back any unused loss to 2008. Accordingly, Groh files amended tax returns for 2007 and 2008, receiving refunds for the $110,000 ($30,000 + $80,000) of taxes paid in those years.

For accounting as well as tax purposes, the $110,000 represents the tax effect (tax benefit) of the loss carryback. Groh should recognize this tax effect in 2009, the loss year. Since the tax loss gives rise to a refund that is both measurable and currently realizable, Groh should recognize the associated tax benefit in this loss period.

Groh makes the following journal entry for 2009.

Groh reports the account debited, Income Tax Refund Receivable, on the balance sheet as a current asset at December 31, 2009. It reports the account credited on the income statement for 2009 as shown in Illustration 19-31.

Since the $500,000 net operating loss for 2009 exceeds the $300,000 total taxable income from the 2 preceding years, Groh carries forward the remaining $200,000 loss.

If a carryback fails to fully absorb a net operating loss, or if the company decides not to carry the loss back, then it can carry forward the loss for up to 20 years.[341] Because companies use carryforwards to offset future taxable income, the tax effect of a loss carryforward represents future tax savings. Realization of the future tax benefit depends on future earnings, an uncertain prospect.

The key accounting issue is whether there should be different requirements for recognition of a deferred tax asset for (a) deductible temporary differences, and (b) operating loss carryforwards. The FASB's position is that in substance these items are the same—both are tax-deductible amounts in future years. As a result, the Board concluded that there should not be different requirements for recognition of a deferred tax asset from deductible temporary differences and operating loss carryforwards.[342]

To illustrate the accounting for an operating loss carryforward, return to the Groh example from the preceding section. In 2009 the company records the tax effect of the $200,000 loss carryforward as a deferred tax asset of $80,000 ($200,000 × 40%), assuming that the enacted future tax rate is 40 percent. Groh records the benefits of the carryback and the carryforward in 2009 as follows.

Groh realizes the income tax refund receivable of $110,000 immediately as a refund of taxes paid in the past. It establishes a Deferred Tax Asset for the benefits of future tax savings. The two accounts credited are contra income tax expense items, which Groh presents on the 2009 income statement shown in Illustration 19-32.

The current tax benefit of $110,000 is the income tax refundable for the year. Groh determines this amount by applying the carryback provisions of the tax law to the taxable loss for 2009. The $80,000 is the deferred tax benefit for the year, which results from an increase in the deferred tax asset.

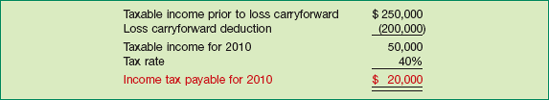

For 2010, assume that Groh returns to profitable operations and has taxable income of $250,000 (prior to adjustment for the NOL carryforward), subject to a 40 percent tax rate. Groh then realizes the benefits of the carryforward for tax purposes in 2010, which it recognized for accounting purposes in 2009. Groh computes the income tax payable for 2010 as shown in Illustration 19-33.

Groh records income taxes in 2010 as follows.

The benefits of the NOL carryforward, realized in 2010, reduce the Deferred Tax Asset account to zero.

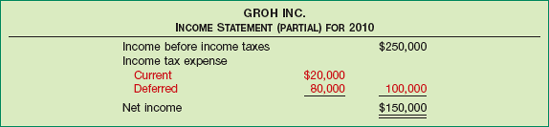

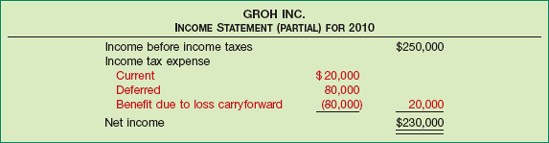

The 2010 income statement that appears in Illustration 19-34 does not report the tax effects of either the loss carryback or the loss carryforward, because Groh had reported both previously.

Let us return to the Groh example. Assume that it is more likely than not that Groh will not realize the entire NOL carryforward in future years. In this situation, Groh records the tax benefits of $110,000 associated with the $300,000 NOL carryback, as we previously described. In addition, it records a Deferred Tax Asset of $80,000 ($200,000 × 40%) for the potential benefits related to the loss carryforward, and an allowance to reduce the deferred tax asset by the same amount. Groh makes the following journal entries in 2009.

The latter entry indicates that because positive evidence of sufficient quality and quantity is unavailable to counteract the negative evidence, Groh needs a valuation allowance.

Illustration 19-35 shows Groh's 2009 income statement presentation.

In 2010, assuming that Groh has taxable income of $250,000 (before considering the carryforward), subject to a tax rate of 40 percent, it realizes the deferred tax asset. It thus no longer needs the allowance. Groh records the following entries.

Groh reports the $80,000 Benefit Due to the Loss Carryforward on the 2010 income statement. The company did not recognize it in 2009 because it was more likely than not that it would not be realized. Assuming that Groh derives the income for 2010 from continuing operations, it prepares the income statement as shown in Illustration 19-36.

Another method is to report only one line for total income tax expense of $20,000 on the face of the income statement and disclose the components of income tax expense in the notes to the financial statements.

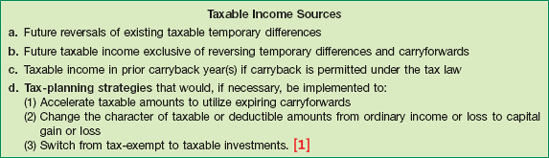

A company should consider all positive and negative information in determining whether it needs a valuation allowance. Whether the company will realize a deferred tax asset depends on whether sufficient taxable income exists or will exist within the carryforward period available under tax law. Illustration 19-37 shows possible sources of taxable income that may be available under the tax law to realize a tax benefit for deductible temporary differences and carryforwards.[343]

If any one of these sources is sufficient to support a conclusion that a valuation allowance is unnecessary, a company need not consider other sources.

Forming a conclusion that a valuation allowance is not needed is difficult when there is negative evidence such as cumulative losses in recent years. Companies may also cite positive evidence indicating that a valuation allowance is not needed. Illustration 19-38 (on page 1011) presents examples (not prerequisites) of evidence to consider when determining the need for a valuation allowance.[344]

The use of a valuation allowance provides a company with an opportunity to manage its earnings. As one accounting expert notes, "The 'more likely than not' provision is perhaps the most judgmental clause in accounting." Some companies may set up a valuation account and then use it to increase income as needed. Others may take the income immediately to increase capital or to offset large negative charges to income.

A recent study of companies' valuation allowances indicates that the allowances are related to the factors identified as positive and negative evidence. And though there is little evidence that companies use the valuation allowance to manage earnings, the press sometimes understates the impact of reversing the deferred tax valuation allowance.

For example, in one year Verity, Inc. eliminated its entire valuation allowance of $18.9 million but focused on a net deferred tax gain of $2.9 million in its press release. Why the difference? As revealed in Verity's financial statement notes, other deferred tax expense amounts totaled over $16 million. Thus, the one-time valuation reversal gave an $18.9 million bump to income, not the net $2.9 million reported in the press.

The lesson: After you read the morning paper, read the financial statement notes.

Source: G. S Miller and D. J. Skinner, "Determinants of the Valuation Allowance for Deferred Tax Assets under SFAS No. 109," The Accounting Review (April 1998).

Deferred tax accounts are reported on the balance sheet as assets and liabilities. Companies should classify these accounts as a net current amount and a net noncurrent amount. An individual deferred tax liability or asset is classified as current or noncurrent based on the classification of the related asset or liability for financial reporting purposes.

A company considers a deferred tax asset or liability to be related to an asset or liability, if reduction of the asset or liability causes the temporary difference to reverse or turn around. A company should classify a deferred tax liability or asset that is unrelated to an asset or liability for financial reporting, including a deferred tax asset related to a loss carryforward, according to the expected reversal date of the temporary difference.

To illustrate, assume that Morgan Inc. records bad debt expense using the allowance method for accounting purposes and the direct write-off method for tax purposes. It currently has Accounts Receivable and Allowance for Doubtful Accounts balances of $2 million and $100,000, respectively. In addition, given a 40 percent tax rate, Morgan has a debit balance in the Deferred Tax Asset account of $40,000 (40% × $100,000). It considers the $40,000 debit balance in the Deferred Tax Asset account to be related to the Accounts Receivable and the Allowance for Doubtful Accounts balances because collection or write-off of the receivables will cause the temporary difference to reverse. Therefore, Morgan classifies the Deferred Tax Asset account as current, the same as the Accounts Receivable and Allowance for Doubtful Accounts balances.

In practice, most companies engage in a large number of transactions that give rise to deferred taxes. Companies should classify the balances in the deferred tax accounts on the balance sheet in two categories: one for the net current amount, and one for the net noncurrent amount. We summarize this procedure as follows.

Classify the amounts as current or noncurrent. If related to a specific asset or liability, classify the amounts in the same manner as the related asset or liability. If not related, classify them on the basis of the expected reversal date of the temporary difference.

Determine the net current amount by summing the various deferred tax assets and liabilities classified as current. If the net result is an asset, report it on the balance sheet as a current asset; if a liability, report it as a current liability.

Determine the net noncurrent amount by summing the various deferred tax assets and liabilities classified as noncurrent. If the net result is an asset, report it on the balance sheet as a noncurrent asset; if a liability, report it as a long-term liability.

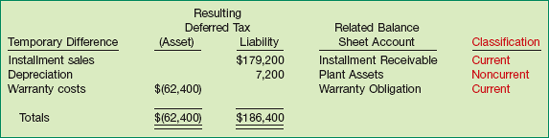

To illustrate, assume that K. Scott Company has four deferred tax items at December 31, 2010. Illustration 19-39 shows an analysis of these four temporary differences as current or noncurrent.

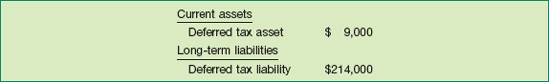

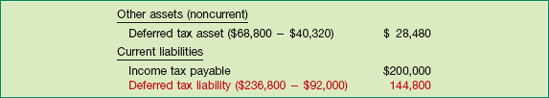

K. Scott classifies as current a deferred tax asset of $9,000 ($42,000 + $12,000 − $45,000). It also reports as noncurrent a deferred tax liability of $214,000. Consequently, K. Scott's December 31, 2010, balance sheet reports deferred income taxes as shown in Illustration 19-40.

As we indicated earlier, a deferred tax asset or liability may not be related to an asset or liability for financial reporting purposes. One example is an operating loss carryforward. In this case, a company records a deferred tax asset, but there is no related, identifiable asset or liability for financial reporting purposes. In these limited situations, deferred income taxes are classified according to the expected reversal date of the temporary difference. That is, a company should report the tax effect of any temporary difference reversing next year as current, and the remainder as noncurrent. If a deferred tax asset is noncurrent, a company should classify it in the "Other assets" section.

The total of all deferred tax liabilities, the total of all deferred tax assets, and the total valuation allowance should be disclosed. In addition, companies should disclose the following: (1) any net change during the year in the total valuation allowance, and (2) the types of temporary differences, carryforwards, or carrybacks that give rise to significant portions of deferred tax liabilities and assets.

Income tax payable is reported as a current liability on the balance sheet. Corporations make estimated tax payments to the Internal Revenue Service quarterly. They record these estimated payments by a debit to Prepaid Income Taxes. As a result, the balance of the Income Tax Payable offsets the balance of the Prepaid Income Taxes account when reporting income taxes on the balance sheet.

Companies should allocate income tax expense (or benefit) to continuing operations, discontinued operations, extraordinary items, and prior period adjustments. This approach is referred to as intraperiod tax allocation.

In addition, companies should disclose the significant components of income tax expense attributable to continuing operations:

Current tax expense or benefit.

Deferred tax expense or benefit, exclusive of other components listed below.

Investment tax credits.

Government grants (if recognized as a reduction of income tax expense).

The benefits of operating loss carryforwards (resulting in a reduction of income tax expense).

Tax expense that results from allocating tax benefits either directly to paid-in capital or to reduce goodwill or other noncurrent intangible assets of an acquired entity.

Adjustments of a deferred tax liability or asset for enacted changes in tax laws or rates or a change in the tax status of a company.

Adjustments of the beginning-of-the-year balance of a valuation allowance because of a change in circumstances that causes a change in judgment about the realizability of the related deferred tax asset in future years.

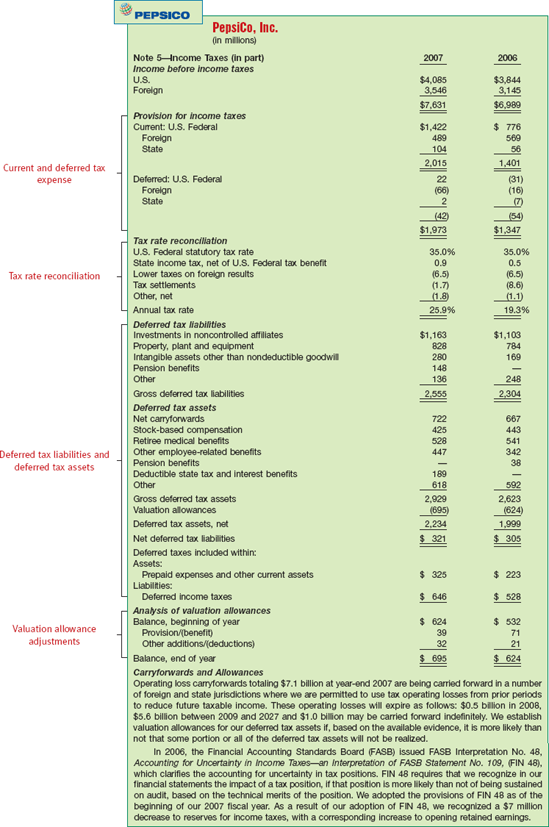

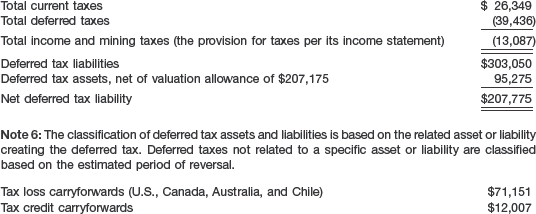

In the notes, companies must also reconcile (using percentages or dollar amounts) income tax expense attributable to continuing operations with the amount that results from applying domestic federal statutory tax rates to pretax income from continuing significant reconciling items. Illustration 19-41 (on page 1014) presents an example from the 2007 annual report of PepsiCo, Inc.

These income tax disclosures are required for several reasons:

Assessing Quality of Earnings. Many investors seeking to assess the quality of a company's earnings are interested in the reconciliation of pretax financial income to taxable income. Analysts carefully examine earnings that are enhanced by a favorable tax effect, particularly if the tax effect is nonrecurring. For example, the tax disclosure in Illustration 19-41 indicates that PepsiCo's effective tax rate increased from 19.3 percent in 2006 to 25.9 percent in 2007 (primarily due to less tax settlements in 2007). This increase in the effective tax rate decreased income for 2007.

Making Better Predictions of Future Cash Flows. Examination of the deferred portion of income tax expense provides information as to whether taxes payable are likely to be higher or lower in the future. In PepsiCo's case, analysts expect future taxable amounts and higher tax payments, due to realization of gains on equity investments, lower deprecation in the future, and higher payments for pension expense. PepsiCo expects future deductible amounts and lower tax payments due to deductions for carryforwards, employee benefits, and state taxes. These deferred tax items indicate that actual tax payments for PepsiCo will be higher than the tax expense reported on the income statement in the future.[345]

Predicting Future Cash Flows for Operating Loss Carryforwards. Companies should disclose the amounts and expiration dates of any operating loss carryforwards for tax purposes. From this disclosure, analysts determine the amount of income that the company may recognize in the future on which it will pay no income tax. For example, the PepsiCo disclosure in Illustration 19-41 indicates that PepsiCo has $7.1 billion in net operating loss carryforwards that it can use to reduce future taxes. However, the valuation allowance indicates that $695 million of deferred tax assets may not be realized in the future.

Loss carryforwards can be valuable to a potential acquirer. For example, as mentioned earlier, Yahoo! has a substantial net operating loss carryforward. A potential acquirer would find Yahoo more valuable as a result of these carryforwards. That is, the acquirer may be able to use these carryforwards to shield future income. However the acquiring company has to be careful, because the structure of the deal may lead to a situation where the deductions will be severely limited.

Much the same issue arises in companies emerging from bankruptcy. In many cases these companies have large NOLs, but the value of the losses may be limited. This is because any gains related to the cancellation of liabilities in bankruptcy must be offset against the NOLs. For example, when Kmart Holding Corp. emerged from bankruptcy in early 2004, it disclosed NOL carryforwards approximating $3.8 billion. At the same time, Kmart disclosed cancellation of debt gains that reduced the value of the NOL carryforward. These reductions soured the merger between Kmart and Sears Roebuck because the cancellation of the indebtedness gains reduced the value of the Kmart carryforwards to the merged company by $3.74 billion.[346]

Here are some net operating loss numbers reported by several notable companies.

NOLs ($ in millions)

All of these companies are using the carryforward provisions of the tax code for their NOLs. For many of them, the NOL is an amount far exceeding their reported profits. Why carry forward the loss to get the tax deduction? First, the company may have already used up the carryback provision, which allows only a two-year carryback period. (Carryforwards can be claimed up to 20 years in the future.) In some cases, management expects the tax rates in the future to be higher. This difference in expected rates provides a bigger tax benefit if the losses are carried forward and matched against future income. Is there a downside? To realize the benefits of carryforwards, a company must have future taxable income in the carryforward period in order to claim the NOL deductions. As we learned, if it is more likely than not that a company will not have taxable income, it must record a valuation allowance (and increased tax expense). As the data above indicate, recording a valuation allowance to reflect the uncertainty of realizing the tax benefits has merit. But for some, the NOL benefits begin to expire in the following year, which may be not enough time to generate sufficient taxable income in order to claim the NOL deduction.

Source: Company annual reports.

Whenever there is a contingency, companies determine if the contingency is probable and can be reasonably estimated. If both of these criteria are met, the company records the contingency in the financial statements. These guidelines also apply to uncertain tax positions. Uncertain tax positions are tax positions for which the tax authorities may disallow a deduction in whole or in part. Uncertain tax positions often arise when a company takes an aggressive approach in its tax planning. Examples are instances in which the tax law is unclear or the company may believe that the risk of audit is low. Uncertain tax positions give rise to tax benefits either by reducing income tax expense or related payables or by increasing an income tax refund receivable or deferred tax asset.

Unfortunately, companies have not applied these provisions consistently in accounting and reporting of uncertain tax positions. Some companies have not recognized a tax benefit unless it is probable that the benefit will be realized and can be reasonably estimated. Other companies have used a lower threshold, such as that found in the existing authoritative literature. As we have learned, the lower threshold—described as "more likely than not"—means that the company believes it has at least a 51 percent chance that the uncertain tax position will pass muster with the taxing authorities. Thus, there has been diversity in practice concerning the accounting and reporting of uncertain tax positions.

As a result, the FASB recently issued rules for companies to follow to determine whether it is "more likely than not" that tax positions will be sustained upon audit. [3] If the probability is more than 50 percent, companies may reduce their liability or increase their assets. If the probability is less that 50 percent, companies may not record the tax benefit. In determining "more likely than not," companies must assume that they will be audited by the tax authorities. If the recognition threshold is passed, companies must then estimate the amount to record as an adjustment to their tax assets and liabilities. (This estimation process is complex and is beyond the scope of this textbook.)

Companies will experience varying financial statement effects upon adoption of these rules. Those with a history of conservative tax strategies may have their tax liabilities decrease or their tax assets increase. Others that followed more aggressive tax planning may have to increase their liabilities or reduce their assets, with a resulting negative effect on net income. For example, as indicated in Illustration 19-41 (on page 1014), PepsiCo recorded a $7 million increase to retained earnings upon adoption of these new guidelines.

The FASB believes that the asset-liability method (sometimes referred to as the liability approach) is the most consistent method for accounting for income taxes. One objective of this approach is to recognize the amount of taxes payable or refundable for the current year. A second objective is to recognize deferred tax liabilities and assets for the future tax consequences of events that have been recognized in the financial statements or tax returns.

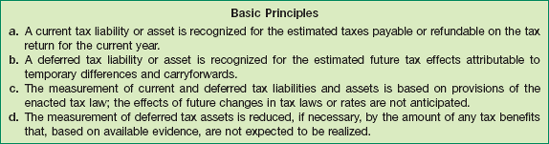

To implement the objectives, companies apply some basic principles in accounting for income taxes at the date of the financial statements, as listed in Illustration 19-42. [4]

Illustration 19-43 diagrams the procedures for implementing the asset-liability method.

As an aid to understanding deferred income taxes, we provide the following glossary.

The accounting for income taxes in iGAAP is covered in IAS 12 ("Income Taxes"). Similar to U.S. GAAP, iGAAP uses the asset and liability approach for recording deferred taxes. The differences between iGAAP and U.S. GAAP involve a few exceptions to the asset-liability approach; some minor differences in the recognition, measurement, and disclosure criteria; and differences in implementation guidance.

The classification of deferred taxes under iGAAP is always noncurrent. As indicated in the chapter, U.S. GAAP classifies deferred taxes based on the classification of the asset or liability to which it relates.

Under iGAAP, an affirmative judgment approach is used, by which a deferred tax asset is recognized up to the amount that is probable to be realized. U.S. GAAP uses an impairment approach. In this approach, the deferred tax asset is recognized in full. It is then reduced by a valuation account if it is more likely than not that all or a portion of the deferred tax asset will not be realized.

iGAAP uses the enacted tax rate or substantially enacted tax rate. ("Substantially enacted" means virtually certain.) For U.S. GAAP, the enacted tax rate must be used.

The tax effects related to certain items are reported in equity under iGAAP. That is not the case under U.S. GAAP, which charges or credits the tax effects to income.

U.S. GAAP requires companies to assess the likelihood of uncertain tax positions being sustainable upon audit. Potential liabilities must be accrued and disclosed if the position is "more likely than not" to be disallowed. Under iGAAP, all potential liabilities must be recognized. With respect to measurement, iGAAP uses an expected-value approach to measure the tax liability, which differs from U.S. GAAP.

The following schedule taken from the annual report of GlaxoSmithKline plc (which uses iGAAP) indicates the impact of differences in iGAAP and U.S. GAAP for deferred taxes.

Thus, due to the differences highlighted above, Glaxo's income tax expense under iGAAP is 251 million pounds higher than that reported under U.S. GAAP.

The FASB and the IASB have been working to address some of the differences in the accounting for income taxes. Some of the issues under discussion are the term "probable" under iGAAP for recognition of a deferred tax asset, which might be interpreted to mean "more likely than not." If the term is changed, the reporting for impairments of deferred tax assets will be essentially the same between U.S. GAAP and iGAAP. In addition, the IASB is considering adoption of the classification approach used in U.S. GAAP for deferred assets and liabilities. Also, U.S. GAAP will likely continue to use the enacted tax rate in computing deferred taxes, except in situations where the U.S. taxing jurisdiction is not involved. In that case, companies should use iGAAP, which is based on enacted rates or substantially enacted tax rates. Finally, the issue of allocation of deferred income taxes to equity for certain transactions under iGAAP must be addressed in order to conform to U.S. GAAP, which allocates the effects to income. At the time of this printing, deliberations on the income tax project have been suspended indefinitely. The FASB has no plans to issue an amendment to its literature at this time, but it may revisit this project after the IASB further develops its replacement to IAS 12.

This appendix presents a comprehensive illustration of a deferred income tax problem with several temporary and permanent differences. The example follows one company through two complete years (2009 and 2010). Study it carefully. It should help you understand the concepts and procedures presented in the chapter.

Allman Company, which began operations at the beginning of 2009, produces various products on a contract basis. Each contract generates a gross profit of $80,000. Some of Allman's contracts provide for the customer to pay on an installment basis. Under these contracts, Allman collects one-fifth of the contract revenue in each of the following four years. For financial reporting purposes, the company recognizes gross profit in the year of completion (accrual basis); for tax purposes, Allman recognizes gross profit in the year cash is collected (installment basis).

Presented below is information related to Allman's operations for 2009.

In 2009, the company completed seven contracts that allow for the customer to pay on an installment basis. Allman recognized the related gross profit of $560,000 for financial reporting purposes. It reported only $112,000 of gross profit on installment sales on the 2009 tax return. The company expects future collections on the related installment receivables to result in taxable amounts of $112,000 in each of the next four years.

At the beginning of 2009, Allman Company purchased depreciable assets with a cost of $540,000. For financial reporting purposes, Allman depreciates these assets using the straight-line method over a six-year service life. For tax purposes, the assets fall in the five-year recovery class, and Allman uses the MACRS system. The depreciation schedules for both financial reporting and tax purposes are shown on page 1022.

The company warrants its product for two years from the date of completion of a contract. During 2009, the product warranty liability accrued for financial reporting purposes was $200,000, and the amount paid for the satisfaction of warranty liability was $44,000. Allman expects to settle the remaining $156,000 by expenditures of $56,000 in 2010 and $100,000 in 2011.

In 2009 nontaxable municipal bond interest revenue was $28,000.

During 2009 nondeductible fines and penalties of $26,000 were paid.

Pretax financial income for 2009 amounts to $412,000.

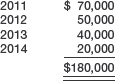

Tax rates enacted before the end of 2009 were:

2009

50%

2010 and later years

40%

The accounting period is the calendar year.

The company is expected to have taxable income in all future years.

The first step is to determine Allman Company's income tax payable for 2009 by calculating its taxable income. Illustration 19A-1 shows this computation.

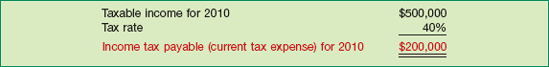

Allman computes income tax payable on taxable income for $100,000 as follows.

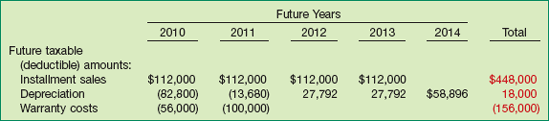

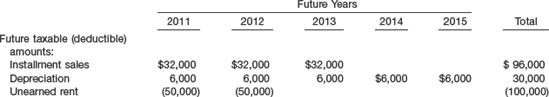

The schedule in Illustration 19A-3 (on page 1023) summarizes the temporary differences and the resulting future taxable and deductible amounts.

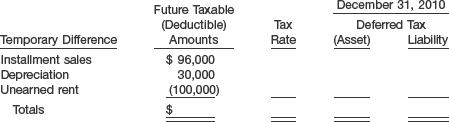

Allman computes the amounts of deferred income taxes to be reported at the end of 2009 as shown in Illustration 19A-4.

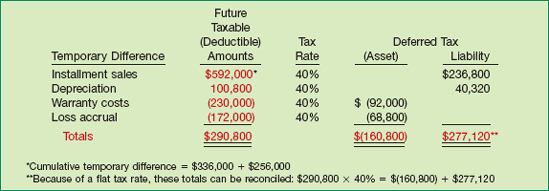

A temporary difference is caused by the use of the accrual basis for financial reporting purposes and the installment method for tax purposes. This temporary difference will result in future taxable amounts, and hence, a deferred tax liability. Because of the installment contracts completed in 2009, a temporary difference of $448,000 originates that will reverse in equal amounts over the next four years. The company expects to have taxable income in all future years, and there is only one enacted tax rate applicable to all future years. Allman uses that rate (40 percent) to compute the entire deferred tax liability resulting from this temporary difference.

The temporary difference caused by different depreciation policies for books and for tax purposes originates over three years and then reverses over three years. This difference will cause deductible amounts in 2010 and 2011 and taxable amounts in 2012, 2013, and 2014. These amounts sum to a net future taxable amount of $18,000 (which is the cumulative temporary difference at the end of 2009). Because the company expects to have taxable income in all future years and because there is only one tax rate enacted for all of the relevant future years, Allman applies that rate to the net future taxable amount to determine the related net deferred tax liability.

The third temporary difference is caused by different methods of accounting for warranties. This difference will result in deductible amounts in each of the two future years it takes to reverse. Because the company expects to report a positive income on all future tax returns and because there is only one tax rate enacted for each of the relevant future years, Allman uses that 40 percent rate to calculate the resulting deferred tax asset.

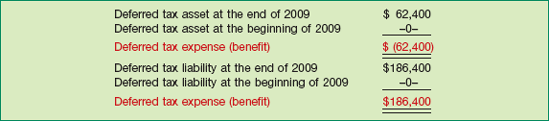

To determine the deferred tax expense (benefit), we need to compare the beginning and ending balances of the deferred income tax accounts. Illustration 19A-5 (on page 1024) shows that computation.

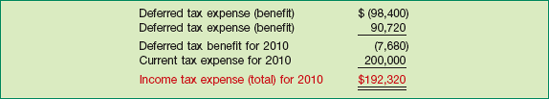

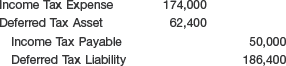

The $62,400 increase in the deferred tax asset causes a deferred tax benefit to be reported in the income statement. The $186,400 increase in the deferred tax liability during 2009 results in a deferred tax expense. These two amounts net to a deferred tax expense of $124,000 for 2009.

Allman then computes the total income tax expense as follows.

Allman records income tax payable, deferred income taxes, and income tax expense as follows.

Companies should classify deferred tax assets and liabilities as current and noncurrent on the balance sheet based on the classifications of related assets and liabilities. Multiple categories of deferred taxes are classified into a net current amount and a net noncurrent amount. Illustration 19A-8 shows the classification of Allman's deferred tax accounts at the end of 2009.

For the first temporary difference, there is a related asset on the balance sheet, installment accounts receivable. Allman classifies that asset as current because it has a trade practice of selling to customers on an installment basis. Allman therefore classifies the resulting deferred tax liability as a current liability.

Certain assets on the balance sheet are related to the depreciation difference—the property, plant, and equipment being depreciated. Allman would classify the plant assets as noncurrent. Therefore, it also classifies the resulting deferred tax liability as noncurrent. Since the company's operating cycle is at least four years in length, Allman classifies the entire $156,000 warranty obligation as a current liability. Thus, it also classifies the related deferred tax asset of $62,400 as current.[347]

The balance sheet at the end of 2009 reports the following amounts.

Allman's income statement for 2009 reports the following.

During 2010 Allman collected $112,000 from customers for the receivables arising from contracts completed in 2009. The company expects recovery of the remaining receivables to result in taxable amounts of $112,000 in each of the following three years.

In 2010 the company completed four new contracts that allow for the customer to pay on an installment basis. These installment sales created new installment receivables. Future collections of these receivables will result in reporting gross profit of $64,000 for tax purposes in each of the next four years.

During 2010 Allman continued to depreciate the assets acquired in 2009 according to the depreciation schedules appearing on page 1022. Thus, depreciation amounted to $90,000 for financial reporting purposes and $172,800 for tax purposes.

An analysis at the end of 2010 of the product warranty liability account showed the following details.

The balance of the liability is expected to require expenditures in the future as follows.

During 2010 nontaxable municipal bond interest revenue was $24,000.

Allman accrued a loss of $172,000 for financial reporting purposes because of pending litigation. This amount is not tax-deductible until the period the loss is realized, which the company estimates to be 2018.

Pretax financial income for 2010 amounts to $504,800.

The enacted tax rates still in effect are:

2009

50%

2010 and later years

40%

Allman computes taxable income for 2010 as follows.

Income tax payable for 2010 is as follows.

The schedule in Illustration 19A-13 summarizes the temporary differences existing at the end of 2010 and the resulting future taxable and deductible amounts.

Allman computes the amounts of deferred income taxes to be reported at the end of 2010 as follows.

To determine the deferred tax expense (benefit), Allman must compare the beginning and ending balances of the deferred income tax accounts, as shown in Illustration 19A-15.

The deferred tax expense (benefit) and the total income tax expense for 2010 are, therefore, as follows.

The deferred tax expense of $90,720 and the deferred tax benefit of $98,400 net to a deferred tax benefit of $7,680 for 2010.

Allman records income taxes for 2010 with the following journal entry.

Illustration 19A-17 (on the next page) shows the classification of Allman's deferred tax accounts at the end of 2010.

The new temporary difference introduced in 2010 (due to the litigation loss accrual) results in a litigation obligation that is classified as a long-term liability. Thus, the related deferred tax asset is noncurrent.

Allman's balance sheet at the end of 2010 reports the following amounts.

The income statement for 2010 reports the following.

SUMMARY OF LEARNING OBJECTIVE FOR APPENDIX 19A

FASB Codification References

FASB ASC 740-10-30-18. [Predecessor literature: "Accounting for Income Taxes," Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No. 109 (Norwalk, Conn.: FASB, 1992).]

FASB ASC 740-10-30-21 & 22. [Predecessor literature: "Accounting for Income Taxes," Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No. 109 (Norwalk, Conn.: FASB, 1992), pars. 23 and 24.]

FASB ASC 740-10-25-6. [Predecessor literature: "Accounting for Uncertainty in Income Taxes," FASB Interpretation No. 48 (Norwalk, Conn.: FASB, 2006).]

FASB ASC 740-10-05. [Predecessor literature: "Accounting for Income Taxes," Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No. 109 (Norwalk, Conn.: FASB, 1992), pars. 6 and 8.]

Explain the difference between pretax financial income and taxable income.

What are the two objectives of accounting for income taxes?

Interest on municipal bonds is referred to as a permanent difference when determining the proper amount to report for deferred taxes. Explain the meaning of permanent differences, and give two other examples.

Explain the meaning of a temporary difference as it relates to deferred tax computations, and give three examples.

Differentiate between an originating temporary difference and a reversing difference.

The book basis of depreciable assets for Erwin Co. is $900,000, and the tax basis is $700,000 at the end of 2011. The enacted tax rate is 34% for all periods. Determine the amount of deferred taxes to be reported on the balance sheet at the end of 2011.

Roth Inc. has a deferred tax liability of $68,000 at the beginning of 2011. At the end of 2011, it reports accounts receivable on the books at $90,000 and the tax basis at zero (its only temporary difference). If the enacted tax rate is 34% for all periods, and income tax payable for the period is $230,000, determine the amount of total income tax expense to report for 2011.

What is the difference between a future taxable amount and a future deductible amount? When is it appropriate to record a valuation account for a deferred tax asset?

Pretax financial income for Lake Inc. is $300,000, and its taxable income is $100,000 for 2011. Its only temporary difference at the end of the period relates to a $70,000 difference due to excess depreciation for tax purposes. If the tax rate is 40% for all periods, compute the amount of income tax expense to report in 2011. No deferred income taxes existed at the beginning of the year.

How are deferred tax assets and deferred tax liabilities reported on the balance sheet?

Describe the procedures involved in segregating various deferred tax amounts into current and noncurrent categories.

How is it determined whether deferred tax amounts are considered to be "related" to specific asset or liability amounts?

At the end of the year, Falabella Co. has pretax financial income of $550,000. Included in the $550,000 is $70,000 interest income on municipal bonds, $25,000 fine for dumping hazardous waste, and depreciation of $60,000. Depreciation for tax purposes is $45,000. Compute income taxes payable, assuming the tax rate is 30% for all periods.

Addison Co. has one temporary difference at the beginning of 2010 of $500,000. The deferred tax liability established for this amount is $150,000, based on a tax rate of 30%. The temporary difference will provide the following taxable amounts: $100,000 in 2011; $200,000 in 2012, and $200,000 in 2013. If a new tax rate for 2013 of 20% is enacted into law at the end of 2010, what is the journal entry necessary in 2010 (if any) to adjust deferred taxes?

What are some of the reasons that the components of income tax expense should be disclosed and a reconciliation between the effective tax rate and the statutory tax rate be provided?

Differentiate between "loss carryback" and "loss carryforward." Which can be accounted for with the greater certainty when it arises? Why?

What are the possible treatments for tax purposes of a net operating loss? What are the circumstances that determine the option to be applied? What is the proper treatment of a net operating loss for financial reporting purposes?

What controversy relates to the accounting for net operating loss carryforwards?

What is an uncertain tax position, and what are the general guidelines for accounting for uncertain tax positions?

In 2011 Conlin suffered a net operating loss of $480,000, which it elected to carry back. The 2011 enacted tax rate is 29%. Prepare Conlin's entry to record the effect of the loss carryback.

Deferred tax liability—current

$38,000

Deferred tax asset—current

$(62,000)

Deferred tax liability—noncurrent

$96,000

Deferred tax asset—noncurrent

$(27,000)

Indicate how these balances would be presented in Youngman's December 31, 2010, balance sheet.

Instructions

Compute taxable income and income taxes payable for 2010.

Prepare the journal entry to record income tax expense, deferred income taxes, and income taxes payable for 2010.

Prepare the income tax expense section of the income statement for 2010, beginning with the line "Income before income taxes."

Excess of tax depreciation over book depreciation, $40,000. This $40,000 difference will reverse equally over the years 2011–2014.

Deferral, for book purposes, of $25,000 of rent received in advance. The rent will be earned in 2011.

Pretax financial income, $350,000.

Tax rate for all years, 40%.

Instructions

Compute taxable income for 2010.

Prepare the journal entry to record income tax expense, deferred income taxes, and income taxes payable for 2010.

Prepare the journal entry to record income tax expense, deferred income taxes, and income taxes payable for 2011, assuming taxable income of $325,000.

Instructions

Compute income taxes payable for 2010.

Prepare the journal entry to record income tax expense, deferred income taxes, and income taxes payable for 2010.

Prepare the income tax expense section of the income statement for 2010 beginning with the line "Income before income taxes."

Depreciation on the tax return is greater than depreciation on the income statement by $16,000.

Rent collected on the tax return is greater than rent earned on the income statement by $27,000.

Fines for pollution appear as an expense of $11,000 on the income statement.

Havaci's tax rate is 30% for all years, and the company expects to report taxable income in all future years. There are no deferred taxes at the beginning of 2010.

Instructions

Compute taxable income and income taxes payable for 2010.

Prepare the journal entry to record income tax expense, deferred income taxes, and income taxes payable for 2010.

Prepare the income tax expense section of the income statement for 2010, beginning with the line "Income before income taxes."

Compute the effective income tax rate for 2010.

Deferred tax liability, January 1, 2010, $40,000.

Deferred tax asset, January 1, 2010, $0.

Taxable income for 2010, $115,000.

Pretax financial income for 2010, $200,000.

Cumulative temporary difference at December 31, 2010, giving rise to future taxable amounts, $220,000.

Cumulative temporary difference at December 31, 2010, giving rise to future deductible amounts, $35,000.

Tax rate for all years, 40%.

The company is expected to operate profitably in the future.

Instructions

Compute income taxes payable for 2010.

Prepare the journal entry to record income tax expense, deferred income taxes, and income taxes payable for 2010.

Prepare the income tax expense section of the income statement for 2010, beginning with the line "Income before income taxes."

Instructions

For each item below, indicate whether it involves:

A temporary difference that will result in future deductible amounts and, therefore, will usually give rise to a deferred income tax asset.

A temporary difference that will result in future taxable amounts and, therefore, will usually give rise to a deferred income tax liability.

A permanent difference.

Use the appropriate number to indicate your answer for each.

______ The MACRS depreciation system is used for tax purposes, and the straight-line depreciation method is used for financial reporting purposes for some plant assets.

______ A landlord collects some rents in advance. Rents received are taxable in the period when they are received.

______ Expenses are incurred in obtaining tax-exempt income.

______ Costs of guarantees and warranties are estimated and accrued for financial reporting purposes.

______ Installment sales of investments are accounted for by the accrual method for financial reporting purposes and the installment method for tax purposes.

______ Interest is received on an investment in tax-exempt municipal obligations.

______ For some assets, straight-line depreciation is used for both financial reporting purposes and tax purposes but the assets' lives are shorter for tax purposes.

______ Proceeds are received from a life insurance company because of the death of a key officer. (The company carries a policy on key officers.)

______ The tax return reports a deduction for 80% of the dividends received from U.S. corporations. The cost method is used in accounting for the related investments for financial reporting purposes.

______ Estimated losses on pending lawsuits and claims are accrued for books. These losses are tax deductible in the period(s) when the related liabilities are settled.

______ Expenses on stock options are accrued for financial reporting purposes.

Instructions

Complete the following statements by filling in the blanks.

In a period in which a taxable temporary difference reverses, the reversal will cause taxable income to be _______ (less than, greater than) pretax financial income.

If a $68,000 balance in Deferred Tax Asset was computed by use of a 40% rate, the underlying cumulative temporary difference amounts to $_______.

Deferred taxes ________ (are, are not) recorded to account for permanent differences.