CHAPTER 2

The Regulatory Push

The regulation of operational risk was globally founded on Basel II and later refined in Basel III. This chapter discusses the regulatory response to the Basel Capital Accords (commonly known as Basel I, Basel II, and Basel III) that were presented by the Basel Banking Committee of the Bank of International Settlements in 1988, 2004, and 2010 and that were intended to provide a robust capital framework and risk management approach for internationally active banks.

The focus of this chapter is on (1) the history of the Basel Accords; (2) the rules of the Basel Accords; (3) the adoption of Basel II in Europe and (4) in the United States; (5) the impact of the financial crisis and resulting European and U.S. regulatory changes, including the Dodd-Frank regulation in the United States; and, finally, (6) the introduction of Basel III and its impact on operational risk management.

HISTORY OF THE BASEL ACCORDS

The Basel Accords were developed by the Bank of International Settlements (BIS), which is headquartered in Basel, Switzerland. The BIS describes its mission and activities as follows:

Our mission is to support central banks' pursuit of monetary and financial stability through international cooperation, and to act as a bank for central banks. To pursue our mission we provide central banks with:

- a forum for dialogue and broad international cooperation

- a platform for responsible innovation and knowledge-sharing

- in-depth analysis and insights on core policy issues

- sound and competitive financial services1

The BIS was originally established in 1930 to assist with the management of reparation loans post World War I, but it soon transitioned into a body that addressed monetary and financial stability through statistical analysis, economic research, and regular meetings between central bank governors and other global financial experts. The BIS has successfully expanded its global reach in recent decades and between 1995 and 2020 grew its membership from 33 member central banks or monetary authorities to 63.

At the time of this writing, the global representation at the BIS accounts for about 95 percent of world GDP and includes the following members:

- Bank of Algeria

- Central Bank of Argentina

- Reserve Bank of Australia

- Central Bank of the Republic of Austria

- National Bank of Belgium

- Central Bank of Bosnia and Herzegovina

- Central Bank of Brazil

- Bulgarian National Bank

- Bank of Canada

- Central Bank of Chile

- People's Bank of China

- Central Bank of Colombia

- Croatian National Bank

- Czech National Bank

- Danmarks Nationalbank (Denmark)

- Bank of Estonia

- European Central Bank

- Bank of Finland

- Bank of France

- Deutsche Bundesbank (Germany)

- Bank of Greece

- Hong Kong Monetary Authority

- Magyar Nemzeti Bank (Hungary)

- Central Bank of Iceland

- Reserve Bank of India

- Bank Indonesia

- Central Bank of Ireland

- Bank of Israel

- Bank of Italy

- Bank of Japan

- Bank of Korea

- Central Bank of Kuwait

- Bank of Latvia

- Bank of Lithuania

- Central Bank of Luxembourg

- Central Bank of Malaysia

- Bank of Mexico

- Bank Al-Maghrib (Central Bank of Morocco)

- Netherlands Bank

- Reserve Bank of New Zealand

- Central Bank of Norway

- National Bank of the Republic of North Macedonia

- Central Reserve Bank of Peru

- Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (Philippines)

- Narodowy Bank Polski (Poland)

- Banco de Portugal

- National Bank of Romania

- Central Bank of the Russian Federation

- Saudi Central Bank

- National Bank of Serbia

- Monetary Authority of Singapore

- National Bank of Slovakia

- Bank of Slovenia

- South African Reserve Bank

- Bank of Spain

- Sveriges Riksbank (Sweden)

- Swiss National Bank

- Bank of Thailand

- Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey

- Central Bank of the United Arab Emirates

- Bank of England (United Kingdom)

- Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (United States)

- State Bank of Vietnam2

Over the years, the BIS has established several standing committees to take on the important financial topics of the day. It was heavily involved in supporting the Bretton Woods System in the early 1970s, and tackled the challenges of cross-border capital flows and the importance of financial regulation in the late 1970s and 1980s. In 1974, the G10 nations3 formed the BIS Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) to address shortcomings in the regulation of internationally active banks:

The Basel Committee comprises 45 members from 28 jurisdictions, consisting of central banks and authorities with formal responsibility for the supervision of banking business. Additionally, the Committee has nine observers including central banks, supervisory groups, international organisations and other bodies. The Committee expanded its membership in 2009 and again in 2014.4

Institutions represented on the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision

| Country/jurisdiction | Institutional representative |

|---|---|

| Argentina | Central Bank of Argentina |

| Australia | Reserve Bank of Australia |

| Australian Prudential Regulation Authority | |

| Belgium | National Bank of Belgium |

| Brazil | Central Bank of Brazil |

| Canada | Bank of Canada |

| Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions | |

| China | People's Bank of China |

| China Banking Regulatory Commission | |

| European Union | European Central Bank |

| European Central Bank Single Supervisory Mechanism | |

| France | Bank of France |

| Prudential Supervision and Resolution Authority | |

| Germany | Deutsche Bundesbank |

| Federal Financial Supervisory Authority (BaFin) | |

| Hong Kong SAR | Hong Kong Monetary Authority |

| India | Reserve Bank of India |

| Indonesia | Bank Indonesia |

| Indonesia Financial Services Authority | |

| Italy | Bank of Italy |

| Japan | Bank of Japan |

| Financial Services Agency | |

| Korea | Bank of Korea |

| Financial Supervisory Service | |

| Luxembourg | Surveillance Commission for the Financial Sector |

| Mexico | Bank of Mexico |

| Comisión Nacional Bancaria y de Valores | |

| Netherlands | Netherlands Bank |

| Russia | Central Bank of the Russian Federation |

| Saudi Arabia | Saudi Central Bank |

| Singapore | Monetary Authority of Singapore |

| South Africa | South African Reserve Bank |

| Spain | Bank of Spain |

| Sweden | Sveriges Riksbank |

| Finansinspektionen | |

| Switzerland | Swiss National Bank |

| Swiss Financial Market Supervisory Authority (FINMA) | |

| Turkey | Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey |

| Banking Regulation and Supervision Agency | |

| United Kingdom | Bank of England |

| Prudential Regulation Authority | |

| United States | Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System |

| Federal Reserve Bank of New York | |

| Office of the Comptroller of the Currency | |

| Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation |

In 1988, the BCBS published the Basel Capital Accord5 (commonly known today as Basel I) to provide a framework for the consistent and appropriate regulation of capital adequacy and risk management in internationally active banks. In 2004, the Basel Committee published a revised framework, which came to be known as Basel II.6 Today, the Basel Committee is made up of five groups: the Policy Development Group, the Supervision and Implementation Group, the Macroprudential Supervision Group, the Accounting Experts Group, and the Basel Consultative Group; each of these groups has task forces and working groups that are formed as needed.

By its own admission, the Basel Committee has no legal authority over member central banks, but it relies on them to commit voluntarily to the standards that it sets:

The BCBS does not possess any formal supranational authority. Its decisions do not have legal force. Rather, the BCBS relies on its members' commitments, as described in Section 5, to achieve its mandate.

Section 5. BCBS members’ responsibilities

BCBS members are committed to:

- work together to achieve the mandate of the BCBS;

- promote financial stability;

- continuously enhance their quality of banking regulation and supervision;

- actively contribute to the development of BCBS standards, guidelines and sound practices;

- implement and apply BCBS standards in their domestic jurisdictions within the pre-defined timeframe established by the Committee;

- undergo and participate in BCBS reviews to assess the consistency and effectiveness of domestic rules and supervisory practices in relation to BCBS standards; and

- promote the interests of global financial stability and not solely national interests, while participating in BCBS work and decision-making.7

However, the U.S. Federal Reserve, along with the majority of member central banks, moved forward with national regulatory implementation of most of the Basel Committee recommendations such that they became mandatory for the banks in their jurisdictions.

As a result of the global economic crisis of 2008, the BCBS implemented further standards focusing on credit and liquidity risk management and further bolstering the capital requirements of global financial institutions. These additional standards are known as Basel III.

RULES OF THE ACCORDS

The Basel Accords outline rules for financial institutions and for the national regulators who supervise those institutions.

Basel I

In 1988, the BIS Basel Committee on Banking Supervision published the “International Convergence of Capital Measurement and Capital Standards” (commonly known then as the Basel Capital Accord and today as Basel I). The report aimed to “secure international convergence of supervisory regulations governing the capital adequacy of international banks” (1988, p. 1). Balin outlined the four “pillars” of Basel I as the Constituents of Capital, the Risk Weights, a Target Standard Ratio, and Transitional and Implementing Agreements.8

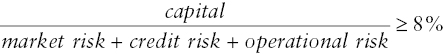

Basel I focused on credit risk and assigned different weightings (0 percent, 10 percent, 20 percent, 50 percent, and 100 percent) for capital requirements, depending on the level of credit risk associated with the asset. Later amendments to Basel I added further weightings to accommodate more sophisticated instruments. The Target Standard Ratio set a minimum standard whereby 8 percent of a bank's risk-weighted assets had to be covered by Tier 1 and Tier 2 capital reserves.

There were no requirements to either manage or measure operational risk under the Basel Accord.

The Basel Accord was adopted with relative ease by the G10 nations that were members of the Basel Banking Committee at that time, including the United States. In the United States, the Basel recommendations were codified in Title 12 of the United States Code and Title 12 of the Code of Federal Regulations.

The Basel Accord (Basel I) was seen as a safety and soundness standard that would protect banks from insolvency, and the minimum capital requirements provided a standard below which regulators would not permit a bank to continue to conduct business. However, regulators soon began to question whether Basel I adequately captured the risks of the increasingly complex and changing financial markets. In addition, banks were able to “game” the system by moving assets off balance sheet and by manipulating their portfolios to minimize their required capital while not necessarily minimizing their actual risk exposure.

Basel II

As pressure mounted for a revised approach, the Basel Committee responded by proposing a revised Capital Adequacy Framework in June 1999. They described the new proposed capital framework as consisting of three pillars: “minimum capital requirements; … supervisory review of an institution's internal assessment process and capital adequacy; and effective use of disclosure to strengthen market discipline as a complement to supervisory efforts.”9

Comments and discussions were held over the next few years, with the newly broadened membership of the Committee providing a global perspective on the proposed changes. The “International Convergence of Capital Measurement and Capital Standards: A Revised Framework” was issued on June 26, 2004, and served as a basis for national rule-making to reflect the Basel II approaches. The Basel Committee outlined the goal of the revised framework as follows:

The Basel II Framework describes a more comprehensive measure and minimum standard for capital adequacy that national supervisory authorities are now working to implement through domestic rule-making and adoption procedures. It seeks to improve on the existing rules by aligning regulatory capital requirements more closely to the underlying risks that banks face. In addition, the Basel II Framework is intended to promote a more forward-looking approach to capital supervision, one that encourages banks to identify the risks they may face, today and in the future, and to develop or improve their ability to manage those risks. As a result, it is intended to be more flexible and better able to evolve with advances in markets and risk management practices.10

On July 4, 2006, the Committee issued an updated version of the revised framework incorporating additional guidance and including those sections of Basel I that had not been revised. The revised framework is almost 10 times the length of Basel I, running to more than 300 pages. For the first time, operational risk management and measurement were required.

Basel II consists of three pillars: Pillar 1—Minimum Capital Requirements, Pillar 2—Supervisory Review Process, and Pillar 3—Market Discipline.

Pillar 1

The major changes to the capital adequacy rules were outlined in detail in Pillar 1. Basel II required banks to hold capital for assets in the holding company, so as to prevent banks from avoiding capital by moving assets around within its corporate structure.

Credit Risk Pillar 1 offered three possible approaches to calculating credit risk: the standardized approach, the foundation internal ratings based (F-IRB) approach, and, finally, the advanced IRB approach.

Under the standardized approach a bank could use “authorized” rating institution ratings in order to assign risk weightings and to calculate capital.

Under the IRB approaches, the banks were able to take advantage of capital improvements on the standardized approach by applying their own internal credit rating models. Under F-IRB, a bank could develop its own model to estimate the probability of default (PD) for individual clients or groups of clients, subject to approval from their local regulators. F-IRB banks were required to use their regulator's prescribed loss given default (LGD) and to calculate the risk-weighted asset (RWA) and the final required capital.

Under advanced IRB (A-IRB), banks could use their own estimates for PD, LGD, and exposure at default (EAD) to calculate RWA and the final required capital.

Market Risk Pillar 1 also provided market risk capital requirements, based mainly on a value at risk (VaR) approach.

Operational Risk Finally, Pillar 1 introduced a new risk category: operational risk. As discussed in Chapter 1, operational risk is defined in Basel II as the “risk of loss resulting from inadequate or failed internal processes, people and systems or from external events. This definition includes legal risk, but excludes strategic and reputational risk.”11

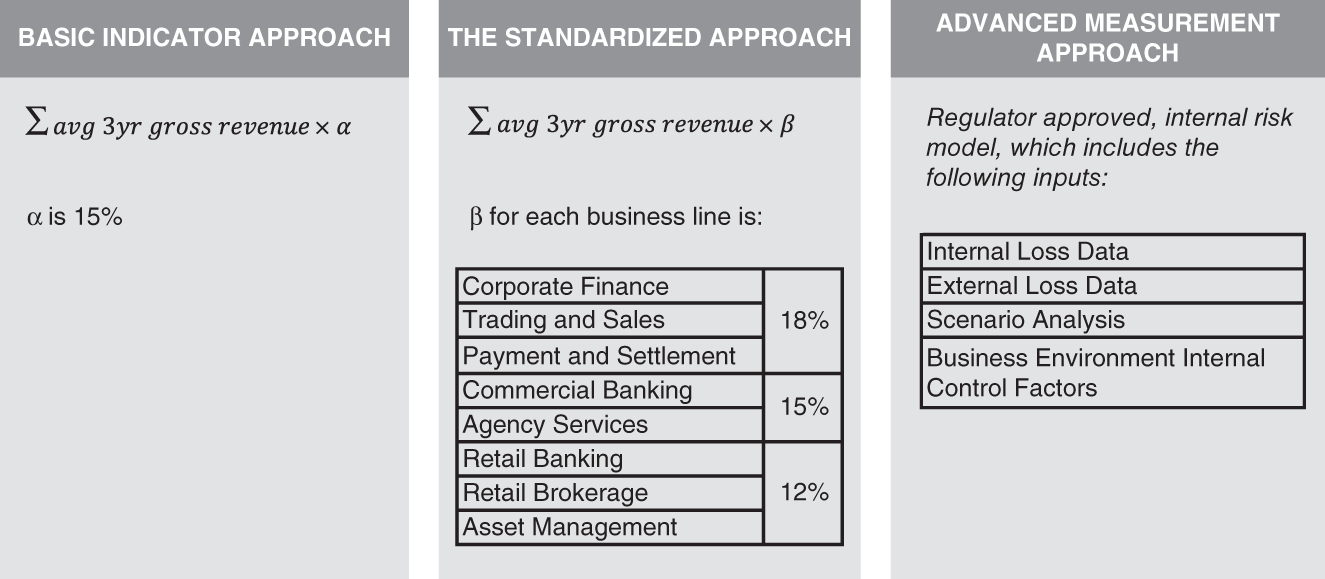

Pillar 1 offered three possible methods to calculate capital for operational risk: the basic indicator approach (BIA), the standardized approach (TSA), or the advanced measurement approach (AMA).12

Under BIA, capital was simply calculated from a percentage (set at 15 percent) of the average of the previous three years' revenue. TSA offered different percentage weightings depending on the business line—ranging from 12 percent for retail banking to 18 percent for sales and trading. AMA offered banks the opportunity to develop their own risk-based model for calculating operational risk capital. AMA required that the model include four elements: internal loss data, external loss data, scenario analysis, and business environment and internal control factors. These three methods are summarized in Figure 2.1.

While Pillar 1 offered three possible methods to calculate operational risk capital, most large banks found that their local regulator required them to pursue an AMA approach. In addition, even where a bank was not required to take an AMA approach to calculating capital, their regulator often advised them that they should adopt best practices and that best practices require them to ensure they have fully developed all four elements of AMA.

Therefore, the standard for a strong operational risk framework is based on the effective development of internal and external loss data systems, appropriate use of scenario analysis, and effective development of business environment and internal control factors.

FIGURE 2.1 Three Capital Calculation Approaches for the Treatment of Operational Risk under Pillar 1 of Basel II

Recent Basel guidance requires banks to adopt a more simplified standardized approach to capital calculation that is driven only by the business activities of the bank and the internal loss history of the bank. However, whether or not the AMA elements are still used as direct inputs into a capital model, they are still considered vital elements of a sound operational risk management framework.

Capital Reserves Finally, under Pillar 1, a bank had to hold capital reserves of at least 8 percent of their total credit, market, and operational risk-weighted assets:

Pillar 2

Basel II introduced Pillar 2 requirements as follows:

This section discusses the key principles of supervisory review, risk management guidance and supervisory transparency and accountability produced by the Committee with respect to banking risks, including guidance relating to, among other things, the treatment of interest rate risk in the banking book, credit risk (stress testing, definition of default, residual risk, and credit concentration risk), operational risk, enhanced cross-border communication and cooperation, and securitization.13

Pillar 2 outlined how the regulators were expected to enforce soundness standards and provided a mechanism for additional capital requirements to cover any material risks that had not been effectively captured in Pillar 1.

Pillar 3

Pillar 3 provided methods for disclosure of risk management practices and capital calculation methods to the public. The purpose of Pillar 3 was to increase transparency and to allow investors and shareholders a view into the inner risk practices of the bank.

ADOPTION OF BASEL II IN EUROPE

In the European Union, Basel II was codified through the European Parliament through the Capital Requirements Directive,14 which required member states to enact appropriate local regulations by January 1, 2007, with advanced approaches available by January 1, 2008.

ADOPTION OF BASEL II IN THE UNITED STATES

In the United States, the plethora of regulators added to the complexities of implementation.

Securities and Exchange Commission Amendments to the Net Capital Rule

U.S. investment banks needed to select a global Basel II regulator, and the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) looked for ways for them to be able to select the SEC as that regulator. To support this, the SEC adopted rules that allowed for consolidated supervised entities (CSEs) to apply to the SEC for regulatory supervision for Basel II. The five large U.S. investment banks took this opportunity: Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley, Bear Stearns, Merrill Lynch, and Lehman Brothers successfully applied for CSE status.

The SEC moved swiftly to make changes to its net capital rules to reflect Basel II standards,15 and the five investment banks were quickly approved for Basel II supervision by the SEC.

U.S. Regulators' Adoption of New Regulations to Apply Basel II

Meanwhile, the remaining U.S. banks were waiting to see whether U.S. banking regulations would be amended to apply the Basel II rules to them. Questions were raised on the appropriateness of the rules, and the audacity of the European Union in driving these global standards was hotly debated in Congress. Pressure was mounting from the regulators and the banks, and international political tensions were increasing as banks waited for the United States to move forward with Basel II rules.

On September 25, 2006, the Federal Banking agencies (the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency [OCC], the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation [FDIC], and the Office of Thrift Supervision [OTS]) came together to collect comments on the adoption of Basel II rules in the United States through two Notices of Proposed Rulemaking relating to capital requirements: New Risk-Based Capital Rules for Large or Internationally Active U.S. Banks in accordance with Basel II, and Market Risk Rule.

On November 2, 2007, the Federal Reserve Board approved final rules to implement new risk-based capital requirements in the United States for large, internationally active banking organizations, stating:

The new advanced capital adequacy framework, known as Basel II, more closely aligns regulatory capital requirements with actual risks and should further strengthen banking organizations' risk-management practices.

‘Basel II is a modern, risk-sensitive capital standard that will protect the safety and soundness of our large, complex, internationally active banking organizations. The new framework is designed to evolve over time and adapt to innovations in banking and financial markets, a significant improvement from the current system,' said Federal Reserve Board Chairman Ben S. Bernanke.16

On July 20, 2008, the Federal Reserve, OCC, OTS, and FDIC reached agreement regarding implementation of Basel II in the United States. There would be mandatory Basel II rules for large banks, and opt-in provisions for noncore banks, as had been proposed in the Notices of Proposed Rulemaking (NPRs).

The new standards were to be transitioned into over a parallel run period, with Basel I–based capital floors being set for the first three years.

Pillar 2 guidance was provided later, resulting in supervisory guidance being published on December 7, 2007.17 The Pillar 2 guidance provided for an Internal Capital Adequacy Assessment Process (ICAAP) for the implementation of Pillar 2 standards in a bank. The final rules were published in the Federal Register, mostly through amendments to Title 12.

IMPACT OF THE FINANCIAL CRISIS

The global economic crisis that began in 2007 led to much soul-searching by governments, regulators, and the BIS as they sought to understand how the Basel frameworks had failed to protect the global economy.

The Limitations of Basel II

Global political pressure resulted in the BIS Basel Committee on Banking Supervision revisiting Basel II to consider what further regulatory and capital enhancements were needed in order to ensure global financial stability. Former – SEC Chairman Christopher Cox himself was vocal about the need for regulatory reform, stating that “in March 2008, I formally requested that the Basel Committee address the inadequacy of the Basel capital and liquidity standards.”18

The Group of Twenty (G20) met regularly to address concerns regarding global regulatory requirements and capital adequacy. They established a Financial Stability Board (FSB) to address these concerns and to make recommendations for change, and the BIS worked closely with the FSB and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to develop new recommendations to enhance the Basel framework. In April 2010, the G20 met to review a report prepared by IMF and FSB and “the main message coming through this document from central banks and regulators is that priority number one is Basel III,” two sources involved in the G20 process said.19

Indeed, the G20 agreed to introduce Basel III by the end of 2012. Proposals for an updating of Basel II were put forward by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision in December 2009 in two documents: “Strengthening the Resilience of the Banking Sector”20 and “International Framework for Liquidity Risk Measurement, Standards and Monitoring.”21 The Committee gathered comments and feedback, and the main recommendations were:

- An increase in Tier 1 capital.

- Additional capital for derivatives, securities financing, and repo markets.

- Tighter leverage ratios.

- Setting aside revenue during upturns to protect against cyclicality of markets.

- Minimum 30-day liquidity standards.

- Enhanced corporate governance, risk management, compensation practices, disclosure, and board supervision practices.

European Response to the Crisis

The Committee of European Banking Supervisors (CEBS) produced the “Guidelines on the Management of Operational Risk in Market Related Activities”22 in October 2010. They placed a heavy emphasis on the importance of strong corporate governance, an area that many saw as one of the key causes of the financial crisis. This document supplemented the earlier “Guidelines on the Scope of Operational Risk and Operational Risk Loss”23 and rounded out the European detailed guidance on the implementation of a robust operational risk framework under Basel II.

This guidance was used by European regulators as a measure against which to assess the operational risk frameworks of European banks.

U.S. Response to the Crisis

The financial turmoil of 2007–2009 resulted in a quick and fundamental change in the way that Basel II was applied to large financial institutions in the United States. Of the original five investment banks that had opted for CSE status with the SEC, three no longer existed as independent entities by 2009: Bear Stearns, Lehman Brothers, and Merrill Lynch. The remaining two, Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley, changed their structures to bank holding companies, and they were now under the regulatory auspices of the Federal Reserve. As a result, the SEC Basel II framework was simply no longer relevant and was formally ended by then-Chairman Christopher Cox on September 26, 2008.24 Chairman Cox maintained that the economic turmoil was not a result of SEC Basel II implementation, but instead that the voluntary opt-in nature of the regulations was to blame.

As I have reported to the Congress multiple times in recent months, the CSE program was fundamentally flawed from the beginning, because investment banks could opt in or out of supervision voluntarily.25

However, there was some speculation and criticism that the SEC had taken a light touch approach to the application of Basel II rules for its five CSEs and that it had, in fact, thereby contributed to the economic crisis. In particular, the high levels of leverage that were permitted by the investment banks were strongly debated, with suggestions that the SEC's CSE rules allowed them to lever up to levels of 30-to-1.26 The operational risk requirements of Basel II did not seem to receive strong enforcement by the SEC, and operational risk frameworks were put under intense scrutiny once the Federal Reserve moved in as the new regulator for the original CSEs.

Morgan Stanley and Goldman Sachs operated their new bank status under the Basel I framework for some time while they sought to be readmitted to the Basel II club under the Federal Reserve's Basel II regulations. The time taken to meet the Federal Reserve standards does suggest that there may be some truth to the suggestion that their previous Basel II framework under the SEC, including the operational risk requirements, may have been relatively, and inappropriately, light.

Banks that were operating under the Federal Reserve's Basel II framework before the economic crisis continued to pursue their Basel II approval with no major changes. However, they noticed an increased vigilance from their regulator as the emphasis on regulatory stringency was on the upswing, and it was clear that Basel III was coming

U.S. Interagency Guidance on Advanced Measurement Approach

In June 2011, the U.S. regulators issued the “Interagency Guidance on the Advanced Measurement Approaches for Operational Risk.”27 This guidance was agreed to by the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, the FDIC, the OCC, and the OTS.

The guidance had been long awaited and addressed several areas where the range of practices in operational risk had been broad among U.S. banks. While some of the conclusions may have been unpopular, the written guidance pointed toward a clearer path to Basel II AMA approval in the United States. However, confusion continued on the appropriate methods for AMA and pressure mounted to simplify the calculation of operational risk capital.

Dodd-Frank Act

In the United States, regulatory reform progressed along similar lines to those that were proposed by G20. President Barack Obama introduced a guidance document, “A New Foundation: Rebuilding Financial Supervision and Regulation,” on June 17, 2009, and 2009 saw many bills introduced that addressed specific aspects of regulatory reform, often overlapping with existing Basel II rules. Davis Polk28 summarized these as follows:

- The Financial Stability Improvement Act as amended by the House Financial Services Committee through November 6, 2009, or the “House Interim Version.”

- The Investor Protection Act, passed by the House Financial Services Committee on November 4, 2009, or the “House Investor Protection bill.”

- The Consumer Financial Protection Agency Act, passed by the House Financial Services Committee on October 29, 2009, or the “House CFPA bill.”

- The Accountability and Transparency in Rating Agencies Act, passed by the House Financial Services Committee on October 28, 2009, or the “House Rating Agencies bill.”

- The Private Fund Investment Advisers Registration Act, passed by the House Financial Services Committee on October 27, 2009, or the “House Private Fund Investment Advisers bill.”

- The Derivatives Markets Transparency and Accountability Act, passed by the House Committee on Agriculture on October 21, 2009, or the “Peterson bill.”

- The Over-the-Counter Derivatives Markets Act, passed by the House Financial Services Committee on October 15, 2009, or the “Frank OTC bill.”

- The Federal Insurance Office Act, introduced by Representative Paul Kanjorski (D-PA) on October 1, 2009, or the “House Insurance bill.”

- The Liability for Aiding and Abetting Securities Violations Act, introduced by Senator Arlen Specter (D-PA) on July 30, 2009, or the “Specter bill.”

- Treasury Proposals released in the summer of 2009, or the “Treasury proposals.”

- The Shareholder Bill of Rights Act, introduced by Senator Charles Schumer (D-NY) on May 19, 2009, or the “Schumer bill.”

These all finally culminated in a catch-all bill, the Restoring American Financial Stability Act of 2009, which was introduced into the Senate by Senator Christopher Dodd (D-CT) and into the House of Representatives by Representative Barney Frank (D-MA). It was subsequently renamed the “Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act,” and President Obama signed the bill into law on July 21, 2010.

The full title of the Act is rather emotive:

An Act to promote the financial stability of the United States by improving accountability and transparency in the financial system, to end “too big to fail,” to protect the American taxpayer by ending bailouts, to protect consumers from abusive financial services practices, and for other purposes.

Dodd-Frank addressed some of the Basel III issues and resulted in U.S. regulatory changes that met many of the Financial Stability Board recommendations. The main elements of Dodd-Frank are outlined in the summary released by the Senate Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs29 under the following categories:

- Consumer Protections with Authority and Independence: The bill creates “a new independent watchdog, Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, housed at the Federal Reserve, with the authority to ensure American consumers get the clear, accurate information they need to shop for mortgages, credit cards, and other financial products, and protect them from hidden fees, abusive terms, and deceptive practices.”

- Ends Too Big to Fail: The bill “ends the possibility that taxpayers will be asked to write a check to bail out financial firms that threaten the economy by: creating a safe way to liquidate failed financial firms; imposing tough new capital and leverage requirements that make it undesirable to get too big; updating the Fed's authority to allow system-wide support but no longer prop up individual firms; and establishing rigorous standards and supervision to protect the economy and American consumers, investors and businesses.”

- Advanced Warning System: The bill “creates a council to identify and address systemic risks posed by large, complex companies, products, and activities before they threaten the stability of the economy.”

- Transparency and Accountability for Exotic Instruments: The bill “eliminates loopholes that allow risky and abusive practices to go on unnoticed and unregulated—including loopholes for over-the-counter derivatives, asset-backed securities, hedge funds, mortgage brokers and payday lenders.”

- Federal Bank Supervision: The bill “streamlines bank supervision to create clarity and accountability and protects the dual banking system that supports community banks.”

- Executive Compensation and Corporate Governance: The bill “provides shareholders with a say on pay and corporate affairs with a non-binding vote on executive compensation.”

- Protects Investors: The bill “provides tough new rules for transparency and accountability for credit rating agencies to protect investors and businesses.”

- Enforces Regulations on the Books: The bill “strengthens oversight and empowers regulators to aggressively pursue financial fraud, conflicts of interest and manipulation of the system that benefit special interests at the expense of American families and businesses.”30

When President Obama successfully entered his second term, any hopes of a full-scale repeal of Dodd-Frank were put to rest. While some changes were made to some of the elements of the Act, much of the main content moved forward into regulation, albeit at a slower pace than had been originally planned, and has remained in place despite another two presidents having been voted into office since President Obama finished his second term.

BASEL III

The Basel Accords have resulted in global regulatory changes that have reached beyond G10, beyond G20, and into the far reaches of the global financial regulatory environment. Basel I introduced credit risk capital measures, and Basel II provided enhanced risk capital calculation for credit, market, and operational risk. The United States has played a key role on the Basel Committee for Banking Supervision, which designed these accords, and so it is not surprising to find that U.S. regulators have consistently adopted these measures.

The economic crisis highlighted the need for further refinements in the way that banks calculate and hold capital for all risk types, and the importance of sound operational risk management and measurement. In addition, it drew close scrutiny of the methods used to ensure there is robust risk management and healthy liquidity in the bank.

In 2010, the BCBS introduced enhanced capital requirements under Basel III so that banks had to maintain more capital of higher quality to cover unexpected losses. They were clear as to the purpose of the Basel III reforms:

The Basel III framework is a central element of the Basel Committee's response to the global financial crisis. It addresses a number of shortcomings in the pre-crisis regulatory framework and provides a foundation for a resilient banking system that will help avoid the build-up of systemic vulnerabilities. The framework will allow the banking system to support the real economy through the economic cycle.31

Minimum Tier 1 capital rose from 4 percent to 6 percent, and at least three-quarters of it had to be of the highest quality (common shares and retained earnings). Global systemically important banks (G-SIBs) were subjected to even higher capital requirements. In other words, the initial approach to the crisis was “hold more capital.”

Basel III was originally scheduled for adoption in January 2013, but that deadline was missed by both the EU and the United States, and a delayed and phased implementation was crafted for implementation over the next few years.

Meanwhile, the writing and implementation of rules under Dodd-Frank and similar nation specific rules across the globe continued at a fast pace. While the operational risk framework remained mostly unchanged since Basel II, the plethora of new regulatory requirements and governance enhancements led to increasing complexity in managing the operational risks faced by a bank on a day-to-day basis.

The 2010 focus of Basel III did not address systemic concerns regarding the variability in methods used by the banks to calculate their overall risk-weighted assets (RWAs) nor the apparent disparity between the riskiness of a bank's portfolio and the calculation of its required capital. This remained an area of concern for the BCBS, and they sought to rebuild the credibility of RWAs as an appropriate risk measure and to bring about greater predictability and consistency across the financial system in the calculation of required capital.

In 2017, the BCBS addressed these issues and released finalized Basel III rules regarding standardized approaches for calculating credit risk, market risk, Credit Valuation Adjustment, and operational risk. These guidelines included a simplified approach to calculating operational risk capital. The BCBS sought to ensure greater risk sensitivity and clearer comparisons between banks with these new standards. In addition, new constraints were introduced on the use of internal models, and floor limits were set in order to limit the benefit that a bank could receive from its preferred capital calculation methods. All of these changes meant that the much-maligned Basel II AMA approach was retired, and all four methods of operational risk capital calculation were replaced by a simpler single standardized method that combines a refined measure of gross income with a bank's own internal loss history over 10 years.

In December 2019, BCBS issued new guidance on this simplified standardized calculation of operational risk capital32 and a final version is due for implementation in January 2023.

In November 2020, BCBS issued a report33 on the progress of its member nations in the implementation of all of the Basel requirements. In it they acknowledged that implementation had been inconsistent and not all deadlines had been met by all nations. In March 2021 they issued “Revisions to the Principles for the Sound Management of Operational Risk.”34

These documents now form the basis for the future regulatory expectations for operational risk and provide additional clarity on the management and measurement of this risk.

BCBS recognized the impact of the global COVID-19 pandemic and confirmed that they would extend the deadline for the adoption of the new operational risk capital standard to January 2023.

Both the Basel II and Basel III capital calculation methods are discussed in Chapter 12 and the revised principles will be discussed throughout this book.

KEY POINTS

- The Basel Accords were developed by the Bank of International Settlements (BIS) to ensure capital adequacy.

- Basel II was first published in 2004, and its full title is “International Convergence of Capital Measurement and Capital Standards: A Revised Framework.”

- Basel II required operational risk management and measurement for the first time.

- There are three approaches to calculating capital for operational risk under Basel II: the basic approach, the standardized approach, and the advanced measurement approach.

- In 2008, the Federal Reserve, OCC, FDIC, and OTS issued a joint requirement for mandatory Basel II rules for large United States banks and opt-in provisions for noncore banks.

- In 2009 and 2010, the CEBS issued guidance on operational risk management and measurement.

- In 2011, U.S. regulators issued the “Interagency Guidance on the Advanced Measurement Approaches for Operational Risk.”

- The United States enacted the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act in July 2010.

- The Act addressed the following areas:

- Consumer Protections with Authority and Independence

- Ends Too Big to Fail

- Advanced Warning System

- Transparency and Accountability for Exotic Instruments

- Federal Bank Supervision

- Executive Compensation and Corporate Governance

- Protects Investors

- Enforces Regulations on the Books

- BCBS issued final Basel II rules in 2017 and further guidance on operational risk capital calculation methods in 2019 and revised sound practices for operational risk management in 2021.

- The global pandemic has delayed the full adoption of Basel III.

REVIEW QUESTIONS

- The full title of Basel II is

- “International Convergence of Capital Measurement and Capital Standards: A Revised Framework.”

- “International Convergence of Capital Accords.”

- “Accord of the Bank of International Settlements.”

- “International Convergence of Capital Measurement and Capital Standards.”

- Pillar 1 provides guidance for

- Three approaches to credit risk.

- Three approaches to operational risk.

- Market risk VaR.

- A minimum capital ratio of 8 percent.

- Liquidity risk ratios.

- I only

- I and II only

- I, II, and III only

- I, II, III, and IV only

- All of the above

NOTES

- 1 “About BIS,” n.d., www.bis.org/about/index.htm.

- 2 “BIS Activities,” n.d., www.bis.org/about/member_cb.htm.

- 3 Central bank and lead financial regulatory representatives from France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, the United States, and Luxembourg.

- 4 “Basel Committee Membership,” n.d., www.bis.org/bcbs/membership.htm.

- 5 Bank of International Settlements, Basel Committee, “International Convergence of Capital Measurement and Capital Standards,” 1988.

- 6 Bank of International Settlements, “International Convergence of Capital Measurement and Capital Standard: A Revised Framework,” 2004.

- 7 “Basel Committee Charter,” n.d., https://www.bis.org/bcbs/charter.htm.

- 8 B. J. Balin, “Basel I, Basel II, and Emerging Markets: A Non-Technical Analysis.” Washington DC: The Johns Hopkins University School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS), 2008, pp. 3–4.

- 9 See note 7.

- 10 “Basel II: Revised International Capital Framework,” n.d., www.bis.org/publ/bcbsca.htm.

- 11 Bank of International Settlements, Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, “International Convergence of Capital Measurement and Capital Standards: A Revised Framework,” Comprehensive Version, 2006, section 644.

- 12 Ibid., p. 144.

- 13 Ibid., p. 204.

- 14 Comprising Directive 2006/48/EC and Directive 2006/49/EC.

- 15 Net Capital Rule Amendments, Securities and Exchange Commission, Release No. 34-49830, 69 Fed. Reg. 34427, June 21, 2004.

- 16 “Risk-Based Capital Standards: Advanced Capital Adequacy,” November 2, 2007. Retrieved from www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/press/bcreg/20071102a.htm.

- 17 “Supervisory Guidance: Supervisory Review Process of Capital Adequacy (Pillar 2) Related to the Implementation of the Basel II Advanced Capital Framework,” 2007.

- 18 Statement of Christopher Cox, former chairman, U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission before the Committee on Financial Services U.S. House of Representatives, April 20, 2010. Retrieved from www.house.gov/apps/list/hearing/…dem/cox_testimony_2010-04-20.pdf.

- 19 “G20 Must Make Basel II Top Priority: Sources,” Reuters, April 20, 2010. Retrieved from www.reuters.com/article/idUSTRE63J2QU20100420.

- 20 “Strengthening the Resilience of the Banking Sector: Consultative Document,” Bank of International Settlements, Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, 2009.

- 21 Ibid.

- 22 www.eba.europa.eu/documents/Publications/Standards—Guidelines/2010/Management-of-op-risk/CEBS-2010-216-(Guidelines-on-the-management-of-op-.aspx.

- 23 Retrieved from http://eba.europa.eu/getdoc/0448297d-3f85-4f7d-9fa6-c6ba5f80895a/CEBS-2009_161_rev1_Compendium.aspx.

- 24 “Chairman Cox Announces End of Consolidated Supervised Entities Program,” SEC Press Release, 2008, 230, www.sec.gov/news/press/2008/2008-230.htm.

- 25 Ibid.

- 26 P. Madigan, “SEC Adoption of Basel II ‘Allowed 30-to-1 leverage,'” Risk, October 29, 2009.

- 27 www.occ.gov/news-issuances/bulletins/2011/bulletin-2011-21a.pdf.

- 28 Davis Polk, “Summary of the Restoring American Financial Stability Act of 2009, Introduced by Senator Christopher Dodd (D-CT) November 10, 2009.” Discussion Draft, 2009.

- 29 Senate Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs, “Summary: Restoring American Financial Stability,” 2009.

- 30 Ibid.

- 31 Bank of International Settlements, Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, “Finalizing Basel II: In Brief,” December 2017, 2, https://www.bis.org/bcbs/publ/d424_inbrief.pdf.

- 32 Bank of International Settlements, Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, “OPE—Calculation of RWA for Operational Risk, OPE25—Standardized Approach,” effective 1 January 2023, https://www.bis.org/basel_framework/chapter/OPE/25.htm?inforce=20230101&published=20200605.

- 33 Bank of International Settlements, Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, “Implementation of Basel Standards: A Report to G20 Leaders on Implementation of the Basel III Regulatory Reforms,” November 2020, https://www.bis.org/bcbs/publ/d510.pdf.

- 34 Bank of International Settlements, Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, “Revisions to the Principles of the Sound Management of Operational Risk,” March 2021, https://www.bis.org/bcbs/publ/d515.htm.