CHAPTER 4

Operational Risk Governance

This chapter addresses the regulatory requirements for operational risk governance and provides alternative governance approaches that can be adopted. The roles and responsibilities of the first, second, and third lines of defense are outlined, as well as the roles and responsibilities of boards of directors, committees, and senior management. Finally, validation and verification requirements are introduced and explained.

ROLE OF GOVERNANCE

Appropriate governance is essential for effective operational risk management, and the people who are responsible for ownership of the operational risk management program will be unable to make a positive impact without a robust governance structure. An effective governance structure must be implemented to provide oversight of operational risk management and measurement and to ensure an effective route for risk escalation.

Governance holds the framework together, as illustrated in Figure 4.1.

The governance approach adopted by a firm needs to reflect the culture of the firm and must be practical in nature. It is not unusual for the creation of an operational risk function to upset the current overall risk governance framework.

One of the main potential challenges in developing and implementing effective operational risk management is that it touches virtually all activities and functions within an organization. Market, credit, and liquidity risk management all evaluate the outcomes and consequences of transactions and other acts of commerce on profitability and balance sheet management. They do not impact the day-to-day running of most of the organization.

Operational risk management, in contrast, evaluates the outcomes and consequences of the organization's ability to perform and execute those risk management activities as well as all other operations, controls, and business functions on which the organization depends in order to remain viable and in business. This broad scope requires a broad governance framework. The board of directors and senior management treat operational risk management with the same level of stature, independence, and authority as the other core risk management disciplines such as market and credit. This core principle of equal stature has evolved steadily over recent years and has become most clearly articulated in various pronouncements by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision.

FIGURE 4.1 The Role of Governance in an Operational Risk Framework

The Basel Committee on Banking Supervision provided the “Principles for Enhancing Corporate Governance”1 in 2010 and included guidance on the governance of risk, including:

Risk management and internal controls

- A bank should have a risk management function (including a chief risk officer (CRO) or equivalent for large banks and internationally active banks), a compliance function and an internal audit function, each with sufficient authority, stature, independence, resources and access to the board;

- Risks should be identified, assessed and monitored on an ongoing firm-wide and individual entity basis;

- An internal controls system which is effective in design and operation should be in place;

- The sophistication of a bank's risk management, compliance and internal control infrastructures should keep pace with any changes to its risk profile (including its growth) and to the external risk landscape; and

- Effective risk management requires frank and timely internal communication within the bank about risk, both across the organization and through reporting to the board and senior management.2

Therefore, a precursor for operational risk governance is the adoption of sound risk governance practices generally.

The Basel Committee on Banking Supervision updated its guidance on operational risk governance in its 2021 publication “Revisions to the Principles for Sound Practices for the Management Operational Risk.”3

Sound internal governance forms the foundation of an effective ORF [operational risk management framework]. Governance of operational risk management has similarities but also differences relative to the management of credit or market risk. Banks' operational risk governance function should be fully integrated into their overall risk management governance structure.4

The role of the board and senior management in ensuring good governance is further expanded in Principles 3, 4, and 5 as follows:

Governance

The Board of Directors

Principle 3: The board of directors should approve and periodically review the operational risk management framework and ensure that senior management implements the policies, processes, and systems of the operational risk management framework effectively at all decision levels.

Principle 4: The board of directors should approve and periodically review a risk appetite and tolerance statement for operational risk that articulates the nature, types and levels of operational risk the bank is willing to assume.

Senior Management

Principle 5: Senior management should develop for approval by the board of directors a clear, effective, and robust governance structure with well-defined, transparent, and consistent lines of responsibility. Senior management is responsible for consistently implementing and maintaining throughout the organisation policies, processes and systems for managing operational risk in all of the bank's material products, activities, processes and systems consistent with the bank's risk appetite and tolerance statement.5

The importance of ownership of operational risk by the board and by senior management is therefore clear, and the governance framework must reflect that ownership in the reporting structure and in the escalation of risk.

In addition, responsibility for good governance of operational risk lies in three lines of defense. These lines are generally considered to be the business, the corporate operational risk function, and independent review by audit.

While these levels of governance might feel weighty for a fintech, there are benefits to having a path for the escalation of risk. Without a strong path for such escalation operational risks can remain quashed in the corners of the organization, only to finally emerge in a large loss event. Early and effective reporting and escalation are key in effectively mitigating risks and so a governance framework, streamlined to fit with the culture and size of the firm, is a worthwhile investment, even for a smaller organization.

FIRST LINE OF DEFENSE

The first line of defense is the business line. The business owns operational risk and should be managing it as it arises. According to the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision:

This means that sound operational risk governance will recognize that business line management is responsible for identifying and managing the risks inherent in the products, activities, processes and systems for which it is accountable.6

Each business line should have an operational risk function in place. The person responsible for operational risk in the business line may have a title such as business risk officer, nonfinancial risk officer, or operational risk manager. They need to maintain independence from the business and so need to have a reporting line that is at the top of the organizational structure. An appropriate reporting line would be to the head of the business or to their chief of staff or chief operating officer.

The expectations of the first line have recently been more clearly outlined as follows:

The responsibilities of an effective first line of defence in promoting a sound operational risk management culture should include:

- identifying and assessing the materiality of operational risks inherent in their respective business units through the use of operational risk management tools;

- establishing appropriate controls to mitigate inherent operational risks, and assessing the design and effectiveness of these controls through the use of the operational risk management tools;

- reporting whether the business units lack adequate resources, tools and training to ensure identification and assessment of operational risks;

- monitoring and reporting the business units' operational risk profiles, and ensuring their adherence to the established operational risk appetite and tolerance statement; and

- reporting residual operational risks not mitigated by controls, including operational loss events, control deficiencies, process inadequacies, and non-compliance with operational risk tolerances.7

Business lines include support functions as well as revenue-generating areas. Therefore, there should be operational risk managers (or their equivalent) in operations, technology, finance, legal, compliance, and human resources as well as in any front office businesses such as fixed income, equities, retail banking, corporate banking, and so on.

The first line of defense operational risk managers might have a direct or dotted reporting line into the second line of defense. The larger and more complex the firm, the more likely it is that the first-line-of-defense operational risk function will be independent from the second-line-of-defense operational risk function.

SECOND LINE OF DEFENSE

The second line of defense is the corporate operational risk function. It is responsible for the development of the operational risk framework and reporting on operational risk matters to the firm's senior management and board of directors. The Basel Committee on Banking Supervision describes the corporate operational risk function, its responsibilities, and its relationship with the business line as follows:

A functionally independent CORF is typically the second line of defence.

The responsibilities of an effective second line of defence should include:

- developing an independent view regarding business units' (i) identified material operational risks, (ii) design and effectiveness of key controls, and (iii) risk tolerance;

- challenging the relevance and consistency of the business unit's implementation of the operational risk management tools, measurement activities and reporting systems, and providing evidence of this effective challenge;

- developing and maintaining operational risk management and measurement policies, standards and guidelines;

- reviewing and contributing to the monitoring and reporting of the operational risk profile; and

- designing and providing operational risk training and instilling risk awareness.

The degree of independence of the CORF may differ among banks. At small banks, independence may be achieved through separation of duties and independent review of processes and functions. In larger banks, the CORF should have a reporting structure independent of the risk-generating business units and be responsible for the design, maintenance and ongoing development of the ORMF within the bank. The CORF typically engages relevant corporate control groups (e.g. Compliance, Legal, Finance and IT) to support its assessment of the operational risks and controls. Banks should have a policy which defines clear roles and responsibilities of the CORF, reflective of the size and complexity of the organisation.8

In order to meet this standard and to be able to effectively challenge the first line of defense and provide valuable reporting to the top of the house, there are two fundamental governance questions to consider for the second line of defense:

- Who should own the operational risk function?

- What should the operational risk function own?

Who Should Own the Operational Risk Function?

While it is critical that the board of directors and senior management demonstrate clear and unequivocal support for operational risk management, it cannot be effectively managed “by committee.” Someone in the firm must be specifically accountable for the success of the operational risk function, or, in other words, they must “own” the operational risk function. The corporate operational risk function needs to report upward in such a way that it is endowed with three critical qualities: independence, importance, and relevance.

When selecting a governance structure for an operational risk function, or when reassessing the current governance of an existing operational risk function, these three qualities should be considered. The governance structure must support the independence of the operational risk function, it must bestow stature and importance of operational risk management and measurement, and it must demonstrate their relevance to the organization. There are various options for the governance of operational risk, and each has practical and strategic advantages and disadvantages.

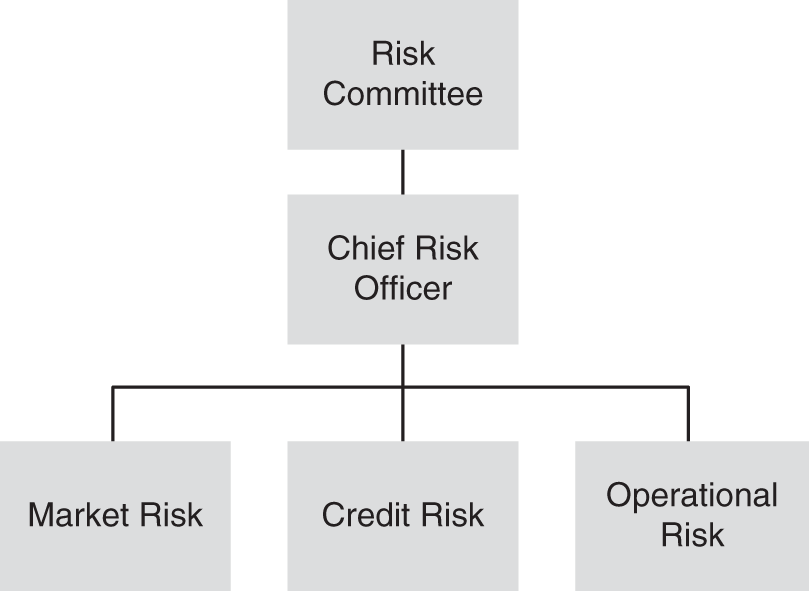

Option 1: Operational Risk Is Owned by the Chief Risk Officer

This governance approach can be represented by the organization chart in Figure 4.2.

An operational risk function that reports directly to the chief risk officer (CRO) is in the fortunate position of being taken seriously by the rest of the organization. This governance structure best demonstrates the seriousness and commitment with which the board and senior management ensures that the operational risk function is independent from both the support and business functions, as it reports directly to the CRO. This reporting line also best reflects the aspirations of many supervisory and regulatory bodies domestically and internationally. In addition, the CRO is generally considered an important and highly relevant function in any firm, and the operational risk department can inherit these qualities in this governance structure.

FIGURE 4.2 Example Governance Structure Where Operational Risk Is Owned by the Chief Risk Officer

The establishment of an independent CRO is recommended by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision in its “Principles for Enhancing Corporate Governance”9 as follows:

Chief risk officer or equivalent

Large banks and internationally active banks, and others depending on their risk profile and local governance requirements, should have an independent senior executive with distinct responsibility for the risk management function and the institution's comprehensive risk management framework across the entire organization. This executive is commonly referred to as the CRO. …

The formal reporting lines and independence of the CRO are further outlined as follows:

Formal reporting lines may vary across banks, but regardless of these reporting lines, the independence of the CRO is paramount. While the CRO may report to the CEO or other senior management, the CRO should also report and have direct access to the board and its risk committee without impediment. Also, the CRO should not have any management or financial responsibility in respect of any operational business lines or revenue-generating functions. Interaction between the CRO and the board should occur regularly and be documented adequately. Non-executive board members should have the right to meet regularly—in the absence of senior management—with the CRO.

The importance and relevance of the CRO is described as follows:

The CRO should have sufficient stature, authority and seniority within the organization. This will typically be reflected in the ability of the CRO to influence decisions that affect the bank's exposure to risk. Beyond periodic reporting, the CRO should thus have the ability to engage with the board and other senior management on key risk issues and to access such information as the CRO deems necessary to form his or her judgment. Such interactions should not compromise the CRO's independence.

If the CRO is removed from his or her position for any reason, this should be done with the prior approval of the board and generally should be disclosed publicly. The bank should also discuss the reasons for such removal with its supervisor.

A head of operational risk who reports to the CRO often enjoys opportunities to sit at the same table as their credit and market risk colleagues. This can help foster an environment where synergies between the risk categories can be identified and can provide the CRO with a more enterprise risk management view. However, there are also potential disadvantages in this governance structure. In practice, operational risk can be overshadowed by market and credit risk if there is only one forum to present all risks at the same time. This can be especially significant if the CRO is from a market or credit risk background. Risk committee meetings can sometimes focus heavily on market and credit risk, to the detriment of operational risk, the latter being relegated to a five-minute briefing at the end of the meeting. A separate dedicated operational risk committee may be needed to overcome this problem. In other words, it may be necessary to augment this governance structure with additional reporting avenues for the operational risk function.

Another potential weakness of this governance structure is the distance it might create between operational risk and its related activities. An effective operational risk function needs to develop strong working relationships with the owners of the existing operational risk activities in the firm. An underlying principle, and a main goal of the Basel standards, is to ensure that operational risk management passes the “use test.” This means that the firm's operational risk management policies, procedures, and tool sets are used by the practitioners who execute the day-to-day activities of the firm throughout its business, control, and support functions. These activities include Sarbanes-Oxley activities in the United States, the business continuity planning and information security teams, legal and compliance departments, and other support departments: operations, finance, and information technology. These functions will not report to the CRO, and finding and cultivating these partnerships will require additional effort by the operational risk team.

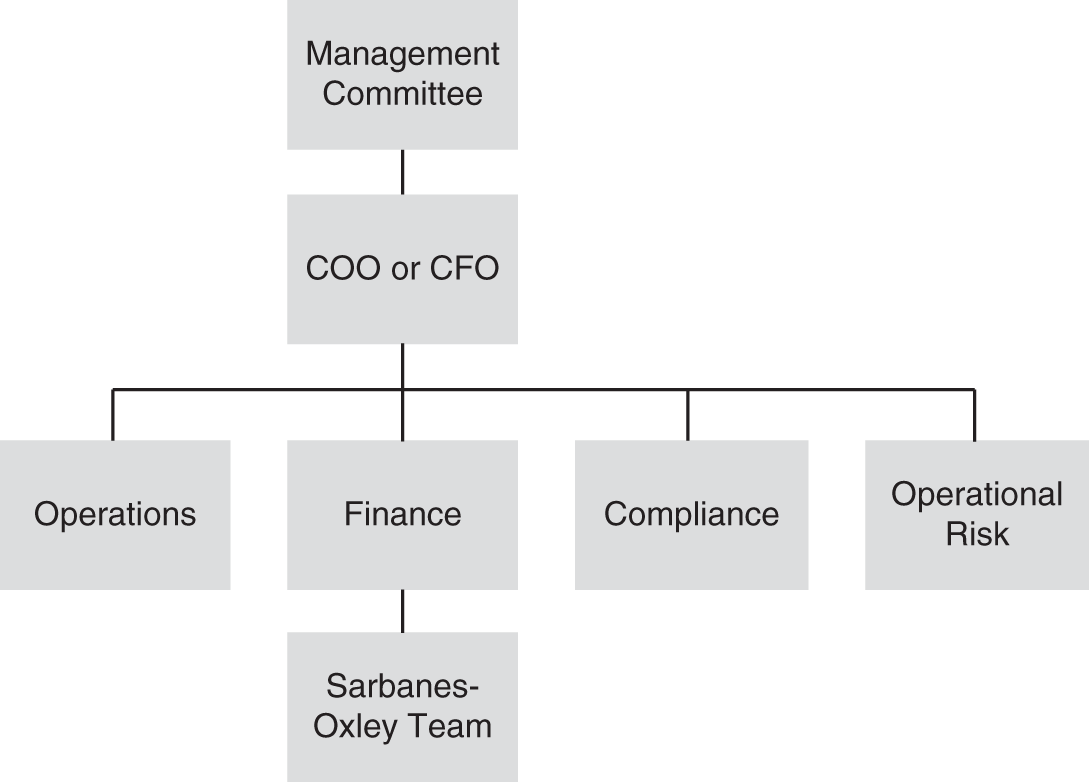

FIGURE 4.3 Example Reporting Structure Where Operational Risk Is Owned by the Chief Operating Officer or the Chief Financial Officer

Option 2: Operational Risk Is Owned by the Chief Operating Officer or the Chief Financial Officer

This governance approach can be represented by the organization chart in Figure 4.3.

In the past, it was common for a firm-wide operational risk department to report to a senior executive such as the chief operating officer (COO), chief financial officer (CFO), or perhaps chief administrative officer (CAO). This structure may be viewed as imbedded in day-to-day operations and therefore not “independent.” Consequently, it has been replaced in most firms by a CRO reporting line, but some do still maintain this type of governance structure. This alternative governance structure has its own advantages and disadvantages.

An operational risk function in such a structure has increased opportunities to partner with the other areas that own operational risks, such as legal and compliance, and the Sarbanes-Oxley team. In fact, the COO or CFO might mandate such working relationships.

As a result, such a governance structure raises the opportunity for governance, risk, and control (GRC) initiatives; GRC is discussed in more depth later in Chapter 16.

The role of the COO, CFO, or CAO should provide the operational risk department with a good level of importance and relevance. However, this structure might weaken the operational risk department's independence. Significant levels of operational risk will exist within the departments that lie within the same reporting structure, and this may hinder the impartiality and objectivity of the operational risk department, or at least tarnish the perception of its independence. Therefore, it is essential that in such a governance structure the operational risk department operates under clear policies and procedures that support its independence.

This governance structure also limits the opportunities for strong partnership with the market and credit risk functions and, therefore, provides less opportunity for an ERM approach.

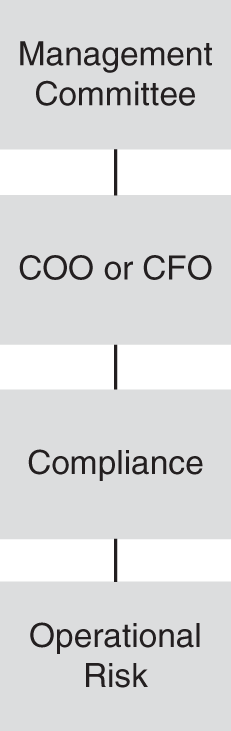

Option 3: Operational Risk Is Owned by the Chief Compliance Officer

This governance approach can be represented by the organization chart in Figure 4.4.

In some firms, generally in smaller and less complex banks and fintechs, the operational risk function reports directly into the compliance department. This is a more unusual arrangement, but for less complex institutions, it has some advantages. There is a clear opportunity to partner closely with the compliance department and also to leverage the reporting cycles, regular meetings, and existing assessment activities that the compliance department may already have in place. The independence of the function can be well maintained in this structure.

FIGURE 4.4 Example Reporting Structure Where Operational Risk Is Owned by the Chief Compliance Officer

The disadvantages of such an approach are that the operational risk function might be perceived to be out of touch with departments that do not usually interact with compliance. Part of the success of operational risk management is self-assessment and self-identification of risk by the day-to-day business, operations, and support practitioners. Self-identification can be inconsistent with the way compliance departments function, and they might be viewed not as a trusted adviser, partner, or risk manager, but rather as a policing function. It may also be harder to demonstrate importance and relevance. As with the option where the operational risk is owned by the COO or CFO, partnerships with market and credit risk could be more challenging and an ERM approach would be difficult to achieve.

What Should the Operational Risk Function Own?

Once the upward-reporting governance structure has been determined, the next challenge is to determine the appropriate downward-reporting structure for the corporate operational risk function. Who should report to operational risk, or what should operational risk own? There are many potential candidates. Whether a function can effectively report to operational risk will depend on several factors: the upward governance structure; the culture of the firm; the individual personalities involved; and the current maturity of the operational risk function in terms of its importance, relevance, and independence.

The following are areas that could report to a central operational risk function.

Other Operational Risk Teams

Each business unit and support function should have its own first line of defense operational risk team. These teams may have been in place earlier than the corporate level function or may have been implemented as a result of the corporate-level commitment to operational risk management. Unlike a corporate-level operational risk function, these teams can report to their own business head or support function head, as they are generally designed to assist that executive in managing the operational risk in their area.

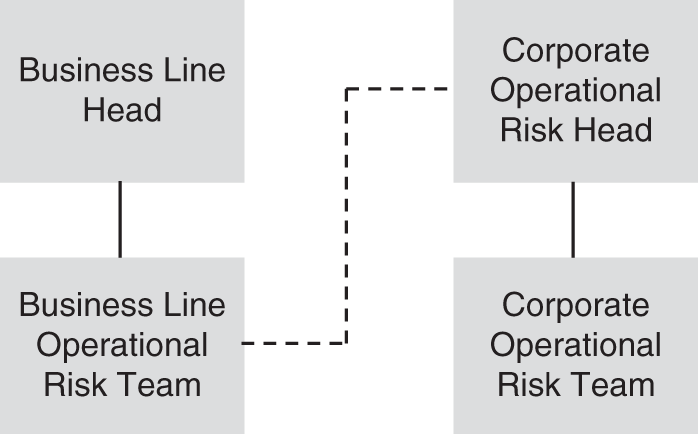

They might also have a dotted-line relationship with the corporate operational risk team. They certainly will have some reporting responsibilities to the corporate function but often do not report directly to them, having at most a matrix reporting structure where they report to both their own division head and the corporate operational risk head. An example of an appropriate reporting structure is shown in Figure 4.5.

FIGURE 4.5 Operational Risk Team Reporting Structure

Embedded Operational Risk Coordinators or Specialists or Managers

The burden of rolling out an operational risk program usually results in a need for a designated operational risk coordinator, operational risk specialist, or operational risk manager in every department. If that department does not have an operational risk function of its own, then this designated individual provides a contact point for the central operational risk function.

An OR coordinator might be required to spend only a small percentage of their time on operational risk activities, and so may have another day job in which they report directly to a manager in their department. There should be a healthy and regular communication between the OR coordinator and the central operational risk team, as the OR coordinator will be the point person for the operational risk team as the operational risk framework is rolled out across the firm.

Such a reporting structure is represented in Figure 4.6.

It can be useful to have such embedded resources also report to the central operational risk function, in a matrix fashion, but this is not essential. Such a reporting structure is represented in Figure 4.7.

FIGURE 4.6 Operational Risk Coordinator Reporting Structure

FIGURE 4.7 Operational Risk Coordinator Matrix Reporting Structure

The relationship between the central operational risk function and the OR coordinator can be informal and still be very successful.

Alternatively, there might be an OR coordinator who is working full time on operational risk activities in a particular department, and who reports directly to the central operational risk function. This can disrupt the clear independence between the first and second lines of defense, but it might be sustainable if there are clear segregation of duties in place and policies to enforce them.

An example of the latter is shown in Figure 4.8.

Business Continuity Planning

Business continuity planning (BCP) is often the most well-established preexisting operational risk function in a firm. BCP generally started life as an information technology function that focused on ensuring that the technology of the firm would continue to function in the case of a disaster. A lot of good BCP work came out of the response of firms to the 9/11 terrorist attack, and many BCP plans were significantly enhanced as a result of lessons learned at that time.

As a result, BCP often focused on disaster recovery plans for technology systems, ensuring that alternate backup sites, data, and systems were available should the main office be compromised for some reason.

Recently, BCP teams have expanded their role to cover other events that might disrupt the business, such as pandemic flu planning. The BCP plans developed for a pandemic raised some new considerations, such as how to ensure business continuity if there were a high level of absenteeism (due to illness) and how to respond to social distancing requirements that might mean that a backup location was not a valid solution (often resulting in an enhanced remote computing contingency plan). These plans have been tested recently as the financial services sector has been challenged by the recent COVID-19 pandemic.

FIGURE 4.8 Embedded Independent Operational Risk Coordinator Reporting Structure

The activities of the BCP team fall squarely within the definition of operational risk, in particular two of the Basel II categories: Damage to Physical Assets and Business Disruption and System Failures.

For this reason, BCP might report to the corporate head of operational risk; this is becoming more and more common in the financial services sector as firms recognize the synergies between the functions.

If there is no direct reporting line from BCP to operational risk, then a strong partnership is essential.

Information Security

The information security function is endowed with the important task of preserving the confidentiality, availability, and integrity of the firm's data, whether it is electronic or otherwise. A failure in this area can result in a serious operational risk event, such as exposing confidential client data, compromising regulatory data compliance requirements, or the loss of vital financial data. Many information security functions started out in a technology department, where they were focused on protecting the security of the technology systems and data.

However, the information held in a firm is often also held in physical forms (such as paper), and the information security function usually provides policies and procedures for the safeguarding of these records also.

The increasingly complex challenges of managing cyber risk, including hacking and ransom attacks, has elevated the information security function to a broader cyber security function that is governed by its own regulatory requirements and assessment approaches.

In order to effectively provide cyber security for the firm's technical infrastructure and data, it is preferable for the function to sit outside of the technology department, as there may be a conflict between the technology department's needs and the information security department's concerns.

For this reason the information security function is often looking for an independent reporting line, and the operational risk function can provide this for them. Also, as information security risk is a subset of operational risk, it is appropriate to link these functions to ensure they effectively leverage each other's expertise and data.

For these reasons, several banks now have their information security function reporting to the operational risk head or the chief risk officer.

Sarbanes-Oxley Act

The Sarbanes-Oxley Act (SOX) imposed operational risk management requirements regarding the accuracy of financial statements on U.S. publicly traded firms. SOX-related activities are therefore a subset of operational risk. However, the SOX team often started in a separate area of the firm (usually in the finance department) and had specific deadlines and compliance requirements to meet. SOX work might also predate the operational risk function, and the SOX team often exists separately from the operational risk team, with a different reporting line (perhaps to the CFO).

SOX assessments are conducted across the firm, and through these assessments, risks and controls are identified and mitigating actions tracked to ensure compliance with SOX.

This overlaps with the risk assessment activities that will be conducted as part of the operational risk program, and for this reason many firms now have their SOX work incorporated into the operational risk function or have the SOX team report to the operational risk head.

In Chapter 16, we look at the ways that these SOX and operational risk activities can be combined in a GRC approach.

New Business Approval or New Product Approval

Financial firms usually have robust new product approval programs that include policies, procedures, and processes to assess and facilitate the review of new products or businesses before they are launched. These new product approval processes require participants to consider all of the risks of the new product, including operational risk. New product approval provides a forum for discussions around the operational practicalities, accounting and tax practices, legal and regulatory requirements, and any other areas that should be addressed before launch.

The operational risk function sometimes administers the new-product approval process, sometimes they are one of the required signatures for approval, and sometimes they might simply require that all other signatories consider operational risk when giving their sign-off.

Policy Office

Many firms are establishing dedicated policy office functions to centralize and standardize firm-wide policies. The operational risk function will be a critical stakeholder in such a function, as they will be designing, mandating, approving, and monitoring policies that manage operational risk. In some cases, the operational risk function might have responsibility for the policy office, and it is embedded in the operational risk function.

The advantage of such an approach is that the operational risk function will have a strong understanding of risk and control requirements and so can provide a strong hand in the development of appropriate and consistent policies.

In the past few years, we have seen a dramatic increase in regulators' interest in policies and procedures. A central repository and a standard template and approach are not just beneficial but are increasingly necessary in order to manage the myriad of regulatory requests regarding policies.

THIRD LINE OF DEFENSE

The third line of defense provides the final internal checks and balances for the operational risk framework. This third line is the internal audit function.

Audit

It is worth noting that the 2021 “Sound Practices” document expressly forbids first- and second-line operational risk functions from reporting to the audit department.

The third line of defence provides independent assurance to the board of the appropriateness of the bank's ORMF. This function's staff should not be involved in the development, implementation and operation of operational risk management processes by the other two lines of defence.10 [emphasis added]

The document then provides an in-depth description of the independent review responsibilities of the audit function.

An effective independent review should:

- review the design and implementation of the operational risk management systems and associated governance processes through the first and second lines of defence (including the independence of the second line of defence);

- review validation processes to ensure they are independent and implemented in a manner consistent with established bank policies;

- ensure that the quantification systems used by the bank are sufficiently robust as (i) they provide assurance of the integrity of inputs, assumptions, processes and methodology and (ii) result in assessments of operational risk that credibly reflect the operational risk profile of the bank;

- ensure that business units' management promptly, accurately and adequately responds to the issues raised, and regularly reports to the board of directors or its relevant committees on pending and closed issues; and

- opine on the overall appropriateness and adequacy of the ORMF and the associated governance processes across the bank. Beyond checking compliance with policies and procedures approved by the board of directors, the independent review should also assess whether the ORMF meets organisational needs and expectations (such as respect of the corporate risk appetite and tolerance, and adjustment of the framework to changing operating circumstances) and complies with statutory and legislative provisions, contractual arrangements, internal rules and ethical conduct.11

The audit function will measure the firm against the operational risk policies and procedures that are in place and will measure the corporate operational risk function against its policies and procedures and its success in designing, maintaining, and monitoring an operational risk framework that meets the firm's regulatory requirements.

Validation

In June 2017, the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) published “Basel III: Finalising post-crisis reforms,” which established that capital calculations had to be based on validated internal loss data.

[Internal loss data] procedures and processes must be subject to validation before the use of the loss data within the operational risk capital requirement measurement methodology, and to regular independent reviews by internal and/or external audit functions.12

This was further clarified in December 2019 when the BCBS issued additional guidance on the appropriate calculation of operational risk capital.”13

The bank's operational risk management processes and assessment system must be subject to validation and regular independent review. These reviews must include both the activities of the business units and of the operational risk management function.14

They also reiterated that independent external validation was also required in order for the regulators to be able to rely on a standardized approach:

The bank's operational risk assessment system (including the internal validation processes) must be subject to regular independent review by internal or external auditors and/or supervisors.15

Firms have been struggling with how best to respond to these validation requirements as they are not specifically in the hands of audit. Some firms have established a validation function that is independent from the rest of the corporate operational risk function and that validates the quantitative and qualitative elements of the framework.

An annual validation program is now in place in several of the firms that have more mature operational risk frameworks. This annual process may include a comparison of data between work streams, for example, comparing loss data to risk and control assessment, and a review of policies and procedures, for example, reviewing committee activities minutes to ensure compliance.

Some firms are also looking at developing rolling validation programs that continuously examine the accuracy and completeness of data.

RISK COMMITTEES

The risk committee structure that is put in place for the escalation and management of operational risk will reflect the first- and second-line-of-defense governance choices made by the firm.

The 2011 “Sound Practices” document provides the following guidance:

When designing the operational risk governance structure, a bank should take the following into consideration:

- Committee structure—Sound industry practice for larger and more complex organizations with a central group function and separate business units is to utilize a board-created enterprise level risk committee for overseeing all risks, to which a management level operational risk committee reports. Depending on the nature, size and complexity of the bank, the enterprise level risk committee may receive input from operational risk committees by country, business or functional area. Smaller and less complex organizations may utilize a flatter organizational structure that oversees operational risk directly within the board's risk management committee;

- Committee composition—Sound industry practice is for operational risk committees (or the risk committee in smaller banks) to include a combination of members with expertise in business activities and financial, as well as independent risk management. Committee membership can also include independent non-executive board members, which is a requirement in some jurisdictions; and

- Committee operation—Committee meetings should be held at appropriate frequencies with adequate time and resources to permit productive discussion and decision-making. Records of committee operations should be adequate to permit review and evaluation of committee effectiveness.16

This document still stands as guidance for operational risk management, but the BCBS has also published updated general guidance on corporate governance that references the roles and responsibilities of the board risk committee, including its oversight of operational risk:

71. A risk committee should:

- be required for systemically important banks and is strongly recommended for other banks based on a bank's size, risk profile or complexity;

- should be distinct from the audit committee, but may have other related tasks, such as finance;

- should have a chair who is an independent director and not the chair of the board or of any other committee;

- should include a majority of members who are independent;

- should include members who have experience in risk management issues and practices;

- should discuss all risk strategies on both an aggregated basis and by type of risk and make recommendations to the board thereon, and on the risk appetite;

- is required to review the bank's risk policies at least annually; and

- should oversee that management has in place processes to promote the bank's adherence to the approved risk policies.

72. The risk committee of the board is responsible for advising the board on the bank's overall current and future risk appetite, overseeing senior management's implementation of the RAS, reporting on the state of risk culture in the bank, and interacting with and overseeing the CRO.

73. The committee's work includes oversight of the strategies for capital and liquidity management as well as for all relevant risks of the bank, such as credit, market, operational and reputational risks, to ensure they are consistent with the stated risk appetite.

74. The committee should receive regular reporting and communication from the CRO and other relevant functions about the bank's current risk profile, current state of the risk culture, utilisation against the established risk appetite, and limits, limit breaches and mitigation plans (…).

75. There should be effective communication and coordination between the audit committee and the risk committee to facilitate the exchange of information and effective coverage of all risks, including emerging risks, and any needed adjustments to the risk governance framework of the bank.17

An example of a risk committee structure that would allow for operational risk to be escalated through the organization is shown in Figure 4.9. In this example the business lines have their own operational risk committees, and separate committees exist for operational risk-related functions in the firm.

FIGURE 4.9 A Sample Risk Committee Structure

Often, many of these committees have different reporting paths up to the board. In those situations, it is important that operational risks are being consistently represented through the various paths that exist.

The board is required to periodically review and approve the framework, and the committee structure can facilitate that process, for example, by requiring risk committee and then board approval as a final step in the validation procedures.

KEY POINTS

- Boards of directors and senior management have specific accountability for operational risk management, including setting appetite and approving frameworks.

- Good governance requires three lines of defense: the first line is the business, the second line is the corporate operational risk function, and the third line is usually the audit function.

- Validation activities must be put in place to ensure the integrity of the operational risk framework and data.

- A risk committee should be established to facilitate risk escalation and framework approval.

- Firms adopt governance structures that meet their business needs and their regulatory requirements locally and globally.

- There are advantages and disadvantages in each governance approach. Some promote ERM, while others promote GRC strategies.

REVIEW QUESTIONS

- Which governance structure is most likely to foster an enterprise risk management view?

- The operational risk department is part of the compliance department.

- The operational risk department reports to the chief risk officer.

- The operational risk department reports to the chief financial officer.

- The operational risk department reports to the chief operating officer.

- Which of the following are requirements of a strong governance structure?

- There are first, second, and third lines of defense.

- The first line of defense is the business line.

- The second line of defense is independent from the first line.

- The second line of defense is owned by the audit function.

- The third line of defense is owned by the business.

- I and II only

- I, II, and III only

- I, II, and IV only

- I, II, and V only

NOTES

- 1 Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, “Principles for Enhancing Corporate Governance,” October 2010, www.bis.org/publ/bcbs176.pdf.

- 2 Ibid., section 3.

- 3 Risk Management Group of the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, “Revision to the Principles of Sound Practices for the Management of Operational Risk,” March 2021, www.bis.org/bcbs/publ/d515.pdf.

- 4 See note 3, section 5.

- 5 See note 3, sections 24–33.

- 6 See note 3, section 9.

- 7 Ibid.

- 8 See note 3, sections 10 and 11.

- 9 See note 1, sections 71–74.

- 10 See note 3, section 12.

- 11 Ibid.

- 12 Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, “Basel III: Finalising Post-crisis Reforms,” December 2017, section 19, www.bis.org/bcbs/publ/d424.pdf.

- 13 Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, “OPEC 25 Standardised Approach,” December 2019, https://www.bis.org/basel_framework/chapter/OPE/25.htm?tldate=20221231.

- 14 Ibid., S25.8 (5).

- 15 Ibid., S25.8 (6).

- 16 See note 3, section 37.

- 17 Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, “Corporate Governance Principles for Banks,” July 2015, https://www.bis.org/bcbs/publ/d328.pdf.