Chapter 5

The Integrated Program Team

We have been exploring how systems thinking is a core aspect of program management beginning with the previous chapter. We began with the need to view the output of a program in terms of a whole solution that meets the expectations of one's customers and end users. We then demonstrated how a systems approach to develop a program architecture will facilitate the creation and delivery of the whole solution. In this chapter we continue the systems approach to program management by exploring how to utilize the whole solution and program architecture to create an integrated program team that can effectively execute the program.

An effective program structure is key to realizing the benefits of program management. Without careful consideration of how an organization's programs are structured, many or all of the benefits of program management will be unrealized. Having said this, however, a surprising number of companies have had difficulties implementing an effective and consistent program team structure.

Our research has revealed that one of the most common errors businesses make in implementing program management is failing to understand the difference between a program team structure and a project team structure. Simply stated, projects, especially larger ones, tend to be vertically structured with multiple layers of organization. Programs, by comparison, require system-level coordination, collaboration, and management. Therefore, they need to be flat and horizontally structured to create the cross-project, cross-discipline network necessary to promote effective collaboration, coordination, communication, and decision making.1 To begin this chapter, we will examine the process involved with forming an integrated program team (IPT).

Structuring an Integrated Program Team

To be successful, a program team must be structured in a manner that facilitates the coordination of its activities and interdependent deliverables, and in a way that promotes effective communication of what is being accomplished by whom and for whom.

As you recall from the discussion in the previous chapter, two key drivers for the formation of the program team structure are the characterization of the whole solution and the design of the program architecture. In effect, the whole solution guides the design of the program architecture and the program architecture guides the structure of the program team. Each of the core and enabling components of the program architecture that will generate deliverables or outcomes required for the program must be represented on the IPT.

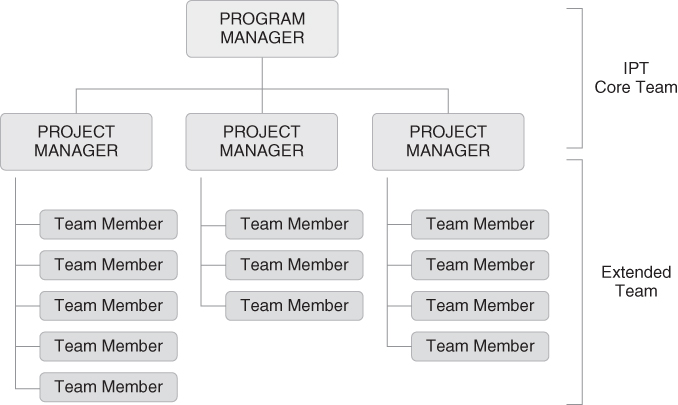

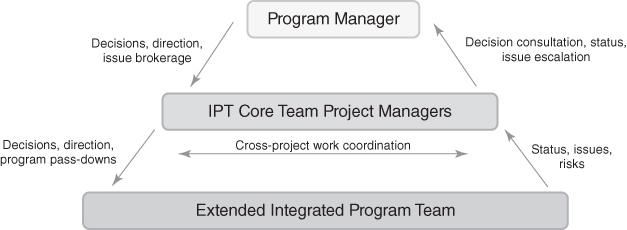

The integrated program team consists of three primary entities as illustrated in Figure 5.1: 1) the program manager, 2) the IPT core team, and 3) the extended team.

Figure 5.1 The IPT team structure.

The particular functions and support organizations that make up the integrated program team are dependent upon the elements and scope of the program architecture. Program team membership may also vary as a program progresses through its life cycle. To remain effective, it is important that the IPT be limited to the key functional representatives within an organization. It is recommended that all programs within an organization be structured in a similar manner for consistency.

The IPT Core Team

The IPT core team is the cross-discipline, cross-project leadership and decision-making body of the program that is responsible for ensuring that the program and business objectives, as well as customer satisfaction, are achieved.2 The IPT core team must become a very cohesive team that has a shared responsibility for the business success of the program. Each member of the core team must be committed to the success of the other members on the team.

The IPT core team consists of the program manager, the project managers, and the functional representatives who provide leadership for the delivery of the elements of their discipline for the program. Collectively the IPT core team constitutes the management team of the program that works under the direction of the program manager.3

The size and make-up of the IPT core team is dependent upon the scope and complexity of a program as defined by the program architecture. Typical IPT core team size varies between four to twelve members, including the program manager.

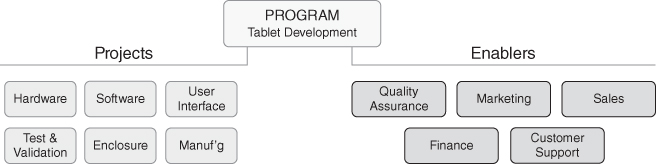

To illustrate, let's look at an example that involves the creation of a product that many of us have come to enjoy using—a tablet mobile device. Figure 5.2 shows a simplified program architecture for the tablet development program.

Figure 5.2 Tablet development program architecture.

The program consists of eleven elements: six projects and five program-enabling functions. In the spirit of form following function, the IPT core team consists of twelve members: the program manager, six project managers, and five discipline-specific representatives for the program enablers, as illustrated in Figure 5.3.

Figure 5.3 Tablet development IPT core team.

This IPT core team is fairly large and is driven by the functional elements needed for the successful development, delivery, and support of the tablet product.

As the leader of the IPT core team, the program manager facilitates the communication and collaboration between the members of the core team (see “An Engineer in Charge of Marketing”). He or she also brokers any conflicts and issues that arise among core team members, between the core team and the functional managers, and between the core team and the stakeholders.4

In the IPT structure, the core team members normally report solid line, or directly, to their specific department or functional manager, and dotted line, or indirectly, to the program manager. Therefore, it is said that core team members wear two hats—the program hat and the functional hat.

This means that the IPT core team members have two sets of responsibilities: program team responsibilities and functional responsibilities. Table 5.1 lists a number of the program and functional responsibilities of the IPT core team members.5

Table 5.1 Core team member program and functional responsibilities

| Program Responsibilities | Functional Responsibilities |

| Deliver their discipline-specific element(s) for the program | Ensure the functional project team is adequately staffed |

| Define and execute the requirements of their functional organization | Ensure adequate expertise exists on the functional project team |

| Develop their project plan and work with the program manager to integrate their project plan into the master program plan | Represent the functional perspective on the program |

| Manage the work commitments for their respective project team | Ensure project specific objectives are met |

| Ensure that functional issues impacting the team are raised proactively within the IPT core team | Identify functional risks and manage the risks within their sphere of influence |

| Work with other IPT core team members to deliver cross-project deliverables | |

| Assist in resolving problems | |

| Drive project level decisions | |

| Assist the program manager in balancing the program constraints | |

| Effectively execute established program processes, methods, and tools |

The Extended IPT

The extended team consists of individual contributors that make up project teams on the program. They can be assigned to the program on either a full-time or part-time basis dependent upon the work they are to accomplish. They are responsible for ensuring their respective project accomplishes all deliverables to the program within schedule and allocated budget, and with full functionality and performance.

The project managers lead the extended team and are the primary decision-makers on each project team. It is common for many of the project teams to be organized in the same horizontal manner as the IPT core team.

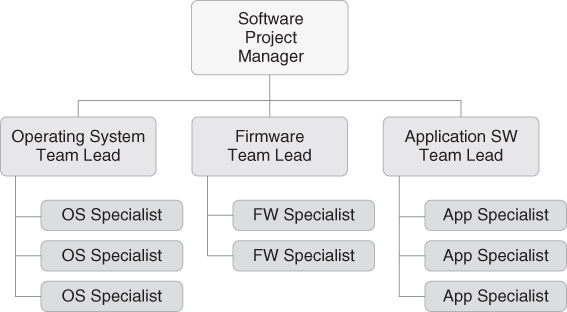

For example, consider a software project manager who is a member of an IPT core team. In addition to representing the software function on the IPT core team, the software project manager also leads the software project team. The project team is likely to have multiple software-specific disciplines represented, such as operating system, software applications, software drivers, and so forth. Each software-specific discipline is therefore likely to have a team lead that is accountable to the project manager as illustrated in Figure 5.4.

Figure 5.4 Example of software project team structure.

Each team lead will have a set of individuals reporting to him or her for the duration of the team's involvement on the program. The individuals are specialists in their respective functional areas or domains.

It should be recognized that most members of the extended IPT are execution specialists who are quite happy working in a well-defined environment. It may take significant work to establish the cross-project collaboration needed in the ever-changing environment of a program.

The IPT Program Manager

As adequately represented in the various program management standards and guidelines, the role of the program manager is separate and distinct from that of the project manager. The program manager is the leader of the program team and is held accountable for its success. In this capacity, the program manager is the champion for the program and has primary influence over the work of the personnel involved on the team.

Although there are many aspects to managing a program, there are a few critical aspects that are directly related to establishing a foundation for effective IPT management.

The program manager needs to work with the project managers to establish the methodologies that will be implemented at the project level. A good program manager will then empower the project managers, but hold them accountable to the rules of the methodology they have chosen.

As advocated by guides and standards, program managers should impose a standard reporting process, format, and content to be consistently utilized across the program. The program manager must then set expectations for use of the reporting process to ensure consistent program and project data.

Lastly, the program manager must establish the governance system for the program. An effective governance system will establish the process through which the IPT core team will coordinate and integrate their work, interact together to create value, and create synergy between the team members. We advocate an integrated governance approach that links program-level governance to the organizational governance system as promoted by the Managing Successful Programmes guide (Chapter 7).6

A Few Words Regarding the Functional Manager

Management of the program occurs at multiple levels of the organization. Executive management sets the business strategy and objectives, the program manager and the IPT core team defines plans and implements the program objectives that help achieve the business objectives, and the project teams are responsible to plan and execute the specialized work to deliver their elements of the program. Additionally, the functional managers ensure that the project teams are adequately staffed and that functional capability is sufficient to achieve the program objectives and realization of the business benefits.

When transitioning from a project orientation to a program orientation, one of the biggest fundamental changes to roles and responsibilities within the firm is that of the organization's functional managers. Under a functional or project-oriented structure, the functional manager has significant power and influence over all or most organized work efforts. However, under a program oriented IPT structure, much of the power and influence for a program shifts to the program manager, with the functional managers providing support to the program for their project team representatives on the program.

Under the IPT core team structure, the functional managers are freed from the daily execution details of a program and can concentrate on the capability growth of their function. They have more time available to focus on their strategic role for the business and their operational responsibilities for hiring, training, and developing the functional specialists within their organization, maintain skills, best practices, and tools to sustain long-term functional expertise. This approach enables the functional managers to make resource and work commitments in support of the program, and assign qualified functional project managers and specialists to represent their function on programs.7

Program managers need the help of functional managers to resolve cross-functional issues and conflicts, assist in making key trade-off decisions, keep programs adequately staffed with skilled resources, and provide technical review of cross-project work. For these reasons alone, program managers must establish good working relationships with the functional managers supporting their programs.

Staffing the Integrated Program Team

The responsibility for ensuring the IPT is adequately staffed falls upon the program manager. He or she is directly responsible for ensuring the IPT core team is fully staffed, while the project managers are directly responsible for staffing their respective project teams. This is not to say that the program manager does not assist the project managers in obtaining the qualified personnel, if necessary.

The program manager is not responsible, however, for selecting the resources for the entire program. Rather, he or she ensures each project manager has the ability to staff their project team with the number of resources required, as well as fulfill critical skill requirements. Where gaps exist in these areas, the program manager will work with functional management, executive management, and the human resources department to fill resource gaps. If critical gaps cannot be filled, changes to the program plan may be required. The program manager should consistently ask for project team staffing reports to ensure the IPT is adequately staffed, especially if there is a change in personnel or a change in requirements and scope.

Critical Factors for IPT Success

One of the primary characteristics of a program is that it is highly integrated and synergistic in nature and is truly a case in which the sum of the parts is more valuable than any of the parts on its own. Additionally, programs tend to be dynamic, with intense cross-discipline integration in which the actions of one project team affect, support, and reinforce the other project teams involved with the program.

Like all other teams, program teams must be effective in team communication and cross-team coordination for repeatable success.

Team Communication

Highly effective teams communicate clearly, consistently, and frequently within the team structure, as well as with stakeholders outside of the team.8 Effective communication permits the program team to make better decisions, evaluate information between the project teams to assess impacts on interdependencies, deal with inter-team conflicts, and keep key stakeholders apprised of program status. The program team structure must enable open, nonhierarchical, and clear communication channels within the team. The program manager and the team leaders must be adept at both vertical and horizontal communication. From a horizontal perspective, the program team must be able to effectively communicate across a wide spectrum of groups and disciplines, including, in some cases, outside suppliers and partners of the firm (see “The Russians Join Us Late at Night”). From a vertical perspective, the program team must be able to communicate effectively with senior management at the top of the organization down through the organization structure to the individual contributors on a program, such as manufacturing operators on the production floor.

Cross-Team Coordination

An effective program team must be able to coordinate and integrate many complex activities and deliverables. Traditional hierarchical and functional team structures are inadequate to address the high level of cross-project coordination that needs to take place in a timely and cost-effective manner.9 The program team structure must horizontally integrate the project teams to enable the program manager to effectively coordinate and channel the work of the teams toward a common output.

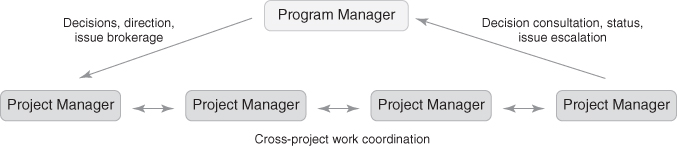

Figure 5.5 illustrates the triangulation of collaboration that takes place on an IPT core team. Directions, decisions, and cross-team issue brokering come from the program manager to the project managers; cross-project communication and work coordination occurs between the project managers; and status, decision consultation, and issue escalation come from the project managers to the program manager.

Figure 5.5 IPT Core team collaboration triangulation.

As illustrated in Figure 5.6, when the third element of the IPT, the extended team, is added, a more traditional project management structure becomes evident at the lower level of the program pyramid.

Figure 5.6 Blended vertical and horizontal coordination.

Decisions, direction, and program pass-downs come from the project managers to the extended program team members. Work status, issues, and detailed risks come from the extended project team members to the respective project managers. The large majority of the cross-project coordination occurs at the core team level, even though some detailed interaction will occur between individual contributors on the project teams.

The horizontal, cross-project structure that the IPT approach provides is key to establishing the shared responsibility and understanding needed to achieve program success. While specialists within an organization's functions are used to collaborating on a daily basis, on a program, coordination between the functional specialists is also necessary.

Let us look at an extreme example of the importance of good cross-project communication and coordination. Nine months after being launched, the Mars Climate Orbiter was lost during its first pass around the red planet. The spacecraft became the victim of poor communication between project teams on the program. One team programmed navigational data to be sent to the Orbiter in English units (feet, inches, and pounds), while another team programmed the Orbiter to receive and interpret the data in metric units (meters, centimeters, and kilograms). The miscommunication resulted in the Orbiter entering the Martian atmosphere at 57 km instead of the intended 140–150 km, and the $125 million spacecraft was destroyed by heat caused by atmospheric friction. Among the primary contributing factors for the loss were the following, which reinforce the importance of good cross-project coordination and communication:10

- The operational navigational team was not fully informed about the details of the way that the Mars Climate Orbiter was pointed in space.

- The systems engineering function within the program that is supposed to track and double-check all interconnected aspects of the mission was not robust enough.

- Some communications channels among project engineering groups were too informal.

- The mission navigation team was oversubscribed and its work did not receive peer review.

Impacts of Geographical Distribution

Program team formation can vary from co-located teams where all members of the program team reside at the same site, to geographically dispersed program teams where members are participating from various physical locations across a nation or around the globe.

A geographically distributed team, also known as a virtual team, is comprised of team members who participate on the IPT, but are separated by time, distance, and sometimes cultural differences. The bond that holds the team members together is the common purpose, vision, and leadership of the program manager. No doubt, the challenges and barriers to leading a geographically distributed team are significantly greater than leading a co-located team due to several factors that include managing across time zones, communication challenges, language barriers, and cultural considerations.

Participation, Collaboration, and Integration

It is important to note, however, that from the program manager's point of view, the foundational elements of effective team leadership and management will continue to work well and are applicable across the entire spectrum of team composition options. Fortunately, success begins with proficiency in the basic principles of team leadership along with the knowledge of how to extend these basic principles into a more complex distributed team environment with inherent differences in team dynamics and communication needs.

Some of the more important leadership principles that must be extended to the distributed team include the following:

Creating a Common Purpose

A geographically distributed team must have a common purpose as the basis for collaboration and participation. A clearly defined common purpose is instrumental in removing ambiguity and should answer four questions:

- What is the purpose? (The business benefits)

- What does the end state look like? (The whole solution)

- What do we need to accomplish to get to the end state? (The business success criteria)

- How will success be measured? (The critical success factors)

Establishing a clear program vision is critical to creating the common purpose needed.

Establishing Team Chemistry

Establishing team chemistry is considerably more complicated within a geographically distributed team because of the cultural diversity considerations and communication challenges caused by language and time zone differences. There are a number of things that successful distributed teams do to accelerate team cohesion, including establishment of team norms for how the team will interact and operate. Additionally, successful teams generate as much social presence and face-to-face interaction among team members as the organization will allow. A third condition to establish team chemistry is the utilization of team-based electronic tools to enhance communication and collaboration.

Building and Sustaining Trust

Trust within a team is the foundation for effective collaboration. For a team to reach peak performance, considerable attention must be paid to building trust among team members and between the program manager and the team members. Trust in the program manager is critical. At a minimum, a program manager must perform competently, follow through on commitments, display concern for the well-being of others on the team, and behave in a consistent manner.

Empowering the Team

Empowering key members of a virtual team to operate autonomously within the boundaries set by the program manager is more critical than with co-located teams because of the physical isolation and distance from the rest of the team. Bottom line, many times some of these team leaders and individual contributors to the program are on their own at their specific company site separated from the rest of the program team that may be hundreds or thousands of miles away.

Team empowerment for a virtual team means giving the project managers and program team members the responsibility and authority to make decisions at the local level. For the program manager, however, greater empowerment of geographically dispersed team members means greater risk for obvious reasons. The greater the empowerment granted to the distributed team members, the less control the program manager maintains.

The most powerful tools available for a program manager to use in establishing effective team empowerment are clearly defined deliverables, identified owners for each deliverable, and decision boundaries based upon success criteria associated with each deliverable.

Communicating Effectively

The three primary elements of effective communication are: 1) listening, 2) reporting, and 3) facilitating. In a geographically distributed team, the selection of the communication tools such as teleconferencing, email, websites, and blogs must be balanced to optimize communication in order to drive the program team's participation, collaboration, and required integration of the team's efforts.

Culturally Blended Teams

Another key difference between co-located and geographically distributed teams is that typically many distributed teams span multiple national, cultural, and linguistic boundaries, contributing additional challenges to the program manager. It therefore becomes necessary for the program manager to learn and embrace the cultural norms, beliefs, and behaviors associated with each country that is represented on the program team. The program manager in this environment must be the champion for cross-cultural leadership and become a role model for good culturally sensitive behavior (see “My Job Was to Integrate Two Cultures”).

At a minimum, the following set of guidelines will help to establish a culturally balanced team environment, which recognizes and utilizes cultural differences as a strength:11

- Suspend judgments. Do not make generalized or stereotypical assumptions about team member's cultures.

- Admit that we don't know. Much of our current knowledge regarding other cultures may be incorrect.

- Show empathy. By listening and caring about others, we learn how other people would like to be treated.

- Systematically check our assumptions. Ask for feedback and constantly make sure you clearly understand the situation.

- Become compatible with ambiguity. Accept the fact that globally dispersed teams will be more complex and that many things will not be totally clear.

- Celebrate diversity. Recognize and espouse the value of differing viewpoints, opinions, and ways of doing things.

With an integrated program team structure in place, an organization becomes well positioned to achieve the business benefits that program management offers an organization such as rapid time-to-benefits, effective management of complexity, establishment of consistent processes and tools for cross-team collaboration, and effective management of resources across the program. Equally important, a program manager has an effective team structure that forms the basis for successful management of a program, the subject of the next chapter.