Chapter 12

Transitioning to Program Management

Organizational transformation is a challenging endeavor. Transitioning to a program-oriented organization is no different. In Chapter 1 we introduced the program management continuum as a way to demonstrate the variations in the use of program management within companies today. At the center of the continuum is an important point that we refer to as the point of transition. This is a philosophical decision point where the senior leaders of an organization make a purposeful decision to transition their organization from being primarily project-oriented to being program-oriented.

A transition to program management can yield significant improvement in a firm's ability to achieve their strategic objectives, competitive position, and financial returns. To realize such improvement requires an awareness, willingness, and commitment to change the organization's culture, overcome internal politics, and establish a new mindset regarding roles, responsibilities, and functions. Crossing the transition point to become a program-oriented organization can affect all levels of management and employees. It changes the rules of engagement, decision-making hierarchies, teams and team structures, and requires competencies different than those prevalent in traditional project-oriented organizations.

Our experiences in leading organizations through this transformation have revealed several key factors that must be managed for success, including:

- First and foremost, there must be a compelling reason to change.

- Senior management must drive the transformation and have a clear vision of the end state.

- Changes to the organizational structure may be required, therefore preplanning to do so is necessary.

- People need to understand their new roles and responsibilities and the new power equation.

- New core competencies may be required within the organization.

- Behavioral change on the part of individuals affected has to be modeled, monitored, managed, and incentivized.

This chapter focuses on the management of these factors relative to the process of change. First, we share commonalities of successful organizations that have made the transition from a project-oriented to program-oriented business. Then we provide the critical elements that constitute a successful change transition, some typical challenges that will need to be overcome, and finally the need for continuous improvement.

Understanding Change

The goal with transitioning to a program management discipline is to achieve a fully functioning model that yields improved business results and do so with as little disruption and pain as possible throughout the transition. To achieve this goal requires understanding change, risks associated with change, and roadblocks that prevent change. The following are helpful in achieving the goal:

- Before starting the transition, know whether or not you really need to change.

- Recognize that successful change is both evolutionary and revolutionary.

- Create a compelling story for change.

- Establish ongoing communication and feedback pertaining to all vested parties.

- Have senior management actively engaged in ensuring the successful implementation of the change.

The Need for Change

There are a number of key factors that typically drive a senior leadership team to decide that program management is needed within their business. The most common factors we have witnessed in working with organizations are detailed in Chapter 2, and summarized below.

Improving alignment between business strategy and execution output. As an organization begins to grow its business, maintaining alignment between work output and strategic intent often becomes a challenge. Simply stated, the link between execution output and strategic goals begins to weaken, and in some firms may eventually break. For many organizations, program management provides value by serving as the organizational glue that can prevent the misalignment between execution and strategy by creating a critical linkage between strategic goals, program objectives, and project deliverables.

Managing increased complexity. The pervasive rise in complexity due to customer demands for more integrated, larger scale and connected solutions has emerged as a primary challenge to the way we have historically operated within our businesses and organizations. For decades, people working to create and deliver complex solutions have used a systems and program-based approach to simplify the levels of complexity they encounter.

Achieving business scalability. As an organization grows, its ability to effectively scale its business processes and consistently deliver positive return on investment can be constrained by a business manager's ability to personally scale. The addition of the program management discipline and skilled program managers removes this constraint as program managers become accountable for delivering the business results for each of their programs.

Improving integration of cross-business functions. Companies continue to be plagued by ineffective collaboration between their business units and divisions caused by parochial behaviors within traditionally siloed functions. The inclusion of program management in a firm's business model can provide value to those organizations by helping them to execute business strategies through the collective efforts of their business functions working to achieve a common vision.

Managing distributed collaboration. The ability to digitize, disaggregate, distribute, produce, and reassemble knowledge work across the globe has created a new business model where highly distributed team collaboration is required. Many companies have come to the realization that they need to adopt a new business model not only to compete, but in many cases to survive. For many, program management provides a management model that specializes in the distribution and reintegration of work.

Now that we understand some important factors involved in the transition decision, we can essentially consider whether to transition to a program-oriented organization. As noted, organizations can find success with either a project- or program-oriented model. Each fits one situation better than another. To decide whether to transition, we devised a simple tool, outlined in Table 12.1, that can be used to guide a discussion and ultimately a decision.

Table 12.1 Decision table for transitioning to program management

| Factor | Project Management | Program Management |

| Degree of linkage between execution output and strategic goals | Loosely connected | Tightly connected |

| Technical complexity | Low | High |

| Structural complexity | Low | High |

| Business complexity | Low | High |

| Level of business scalability | <6 large work efforts | >6 large work efforts |

| Business function interdependency | Low | High |

| Multi-site team distribution | Less than 5 sites | More than 5 sites |

In Table 12.1 we list which of the two approaches may be a better fit based on eight factors. This table can be used as a guide in the assessment, discussion, and decision to transition to a program management model. When using this table, we recommend first tailoring the factors for your specific case, and then determine if each factor favors project or program management by placing an “X” beside your choice.

If the majority of “X's” are on the project management side, do not transition to program management. If, however, the majority of “X's” are on the side of program management, you may have the justification to prepare a case for transition. A word of caution may be of help here. This is a simple but practical tool to make your transition decision. Like any other tool, it is only as good as the information contained in it and the discussion that occurs from it. Therefore, prepare high-quality information for your case and assess the factors completely, critically, and professionally among senior decision makers within your firm.

If the decision is made to transition to program management, we recommend creating a business case for such a transition as outlined in Chapter 6. Use the business factors and operational factors to guide the business case and discussion regarding the transition. Further, don't forget about the need to plan for and overcome communication challenges (build a compelling story), active management support (ensure senior management engagement), and mitigate possible in-fighting due to politics, defending turf, and power tripping.

Transition Is Both Evolutionary and Revolutionary

To obtain the broad-based benefits from applying program management to the business model of the firm, several fundamental changes are required. As noted earlier in this chapter, to achieve a successful transition to program management requires an awareness, a willingness, and a commitment to change the organization's culture, overcome internal politics, and establish a new mindset regarding roles, responsibilities, and functions. This affects all levels of management as it changes the rules of engagement, decision-making hierarchies, and team structures, and requires competencies different than project-oriented organizations. To achieve such change requires time, which is the reason we use the word “transition” throughout this chapter. Transition is meant to imply changes are being realized over time—evolutionary. On average, we have consistently witnessed the transition taking three to four years. This is from transition decision to fully functional program management operations.

The successful transition to a program-oriented organization requires the senior management team of the firm to consciously decide that they will make the fundamental structural and cultural changes necessary to move the organization to program management and lead the implementation of changes. This decision is revolutionary, as are some of the fundamental changes that are required, such as changes to roles and responsibilities, changes to decision-making empowerment, changes to the organizational structure, and changes to the incentive systems. Therefore, success in transforming an organization to a program management discipline is both evolutionary and revolutionary.

Create a Compelling Story for Change

Transition success begins with creating and communicating a compelling story for change.1 A compelling story is necessary because, prior to any change, people must first understand why the change is needed. Beyond just understanding why the change is needed, importantly the employees must agree with the change before actually changing. To accomplish this, you need a compelling story.

There are three points to remember when crafting a compelling story. First, what motivates you may not motivate everyone. Some people may be motivated by a compelling story about how to positively impact society. Others may be focused on maximizing customer satisfaction. Others may be interested in achieving the highest level of financial return. Others yet may be focused on self—what's in it for me. A compelling story will focus on all (or at least multiple) areas of motivation—self, organization, customers, and society.

The second point to remember in creating a compelling story for change is that the story is best written by the employees. Often, position-level leadership (the CEO, for example) writes and conveys the story. The highest probability for sustainable change occurs when employees can write their own story. In this case, the leaders' role is to clarify the situation (problem or opportunity) from which others set the change in motion relative to their story—what we need to do, what we can do, what we will do—and then the leaders establish commitment, responsibility, and accountability to enact the change. This establishes a culture of employees being involved with the change rather than having the change imposed upon them.

The third point to remember in creating a compelling story for change is relative to the problem or opportunity. Sometimes senior leaders get in a pattern of promoting change because of a problem—not enough units sold, not enough market share, not enough profit margin, and the like. Other times, the pattern may be about opportunity—chasing best practices regarding one thing or another. This can be tiring for individuals and organizations at large; the results could be change fatigue in which case creating a compelling story and establishing a sense of urgency lose meaning due to desensitization to the need for change. To be effective, the compelling story needs to balance problem and opportunity.

Senior Management Sponsorship

Firms that have been most successful in transitioning to a program management model have had strong sponsorship from the senior management team of the organization. Implementation of the model works best when it is managed from a top-down approach, rather than a bottom-up approach. When senior management buys into the approach and drives the implementation, the rest of the organization begins to fall in line. It is difficult to derive the necessary and significant changes in an organization when it is attempted through middle management, because barriers within the functional organizations quite often become too difficult to overcome. Coupling this point of sponsorship with the need for a compelling story, as noted above, senior leaders can push for change (from the top), but are most successful when engaging staff in making sense of the change and detailing the story for change.

One senior executive told us how his first attempt at implementing program management within an organization was a complete failure. As he told us, “The transition failed because it didn't have executive support and, worse yet, the executives weren't even open to learning about the value of program management.” This was an organization that was too hard to move without top management supporting and driving the transition and necessary change in culture. According to the senior executive, their philosophy was, “If a person was not a technologist, he or she wouldn't be able to lead a development team.” This is a common problem encountered in technology or engineering companies, making the transition to program management much more difficult than in other types of organizations.

Success most often occurs when the senior sponsor is an influential change agent with a compelling story for change. This means someone with sufficient power, influence, and respect in the organization; someone who can ensure that the organizational structure, behavior, and culture move in a new direction. The change agent must have a clear vision of what the change is and why it is important for the success of the organization. This value proposition should be sufficient for the senior executive to champion the change.

Executing the Program Management Transition

Before transitioning to program management, a firm foundation has to be established from which to build upon. This foundation consists of a strategically focused management philosophy and strong senior management engagement.

Senior management's philosophy as to whether they choose to view project work strategically and linked to the success of the business, or rather to view the efforts as tactical and operational in nature, is critically important for a successful transition to program management. For a program manager and his or her program team to perform at their highest potential, senior management of the firm must make it apparent that they believe the team's efforts are directly tied to the success of the business and are integral to the strategic success of the enterprise. With this view in place, it elevates the importance and resulting influence of the program managers and enables them to coalesce action to get things done.

Additionally, senior management should position program management as a critical business function within the organization. This will enable transition success. Senior management must be careful to preserve the functional neutrality of the program management function. Firms that view program management as a true functional discipline that is equal in influence to other functions of the organization experience increased program management talent and capability, ensure the long-term viability of the discipline, and potentially develop future business leaders for the enterprise.

The phrase “actions speak louder than words” is common. In a world where most executives espouse values such as integrity, honesty, respect, quality, stakeholder satisfaction, and the like, differentiation cannot be found in the words, but rather in actions. The same holds true when leading change. It is not enough when senior leaders simply agree to a change effort, nor is it enough to simply fund the effort. One of the things that separates industry leaders from followers is a senior management team that is actively engaged in planning, leading, and sustaining change.

Whether you are an executive or not, walking your talk is an individual skill that can create corporate identity and distinction. Importantly, as James Kouzes and Barry Posner noted, when values such as integrity are agreed upon and reinforced throughout an enterprise, productivity increases, corporate loyalty is strengthened, teamwork is embraced, and change becomes easier.2 Performance—success or failure—is always the product of the actions from people, not the words in a report or on a poster in the foyer at corporate headquarters.

Transitioning Methodologies

Once a strong program management foundation is established, transition to a program-oriented organization can begin. Many day-to-day tasks have to be managed during the transition, but several structural and cultural elements also need to be in focus for a successful transition.

Many methods to explain transformation have been published. Some are highly academic, others are highly technical, some are more useable than others, and all of them have shortcomings. The challenge is that many tools and models for change explain why change is needed, yet are rather superficial when it comes to explaining how best to transition an organization.

Explaining how to transition is difficult because of the uniqueness of organizations, their strategies, their culture, their situation. It is for this reason—uniqueness—that we recommend having a qualified organizational development expert within the business or an experienced organizational change consultant to lead the transition process and team. Experienced individuals in this field have the requisite skills to navigate over or around the barriers that will be encountered and they represent a neutral position within the company, both of which are necessary to properly plan, lead, and sustain organizational change. Having said that, it is valuable to become familiar with popular change models for reference purposes and for a starting place for planning your transition. Although dozens of models exist, some popular models include Marvin Weisbord's six-box model,3 William Bridges' three-stage model,4 and John Kotter's eight-step process.5 These models and others were studied by Sergio Fernandez and Hal Rainey in a meta-analysis of organizational change models, processes, and practices. They concluded that there are eight common factors among organizational change models.6 These factors include a common understanding of the needs, a plan, internal support, means to overcome resistance, top management support and commitment, external support, resources, institutionalization of the change, and a desire to accomplish even more comprehensive change.

Our experience is that while these models exist, most attempts to plan, lead, and sustain organizational change fail. Change transition success in reality has little to do with the change model implemented, and much to do about changing behavior and overcoming political resistance. While these models can be used to provide a framework for what needs to be done during an organizational transition, they fall short on advice on how to do it. Based on our experience working with organizations involved in program management transition, we have been able to extract a common and repeatable process used by these organizations. This process is presented in Table 12.2.

Table 12.2 Best practices for program management transition

| Transition Step | Required Action |

| 1. Point of transition decision | Senior leaders realize a systemic problem is plaguing them (misalignment between execution and strategy, growing complexity, business scalability challenge) and make the decision to embark on a program management transition. |

| 2. Assign a transition owner | A senior leader is appointed as transition sponsor and assigned responsibility for assessing the need for transition and to lead the transition effort. |

| 3. Establish a broad knowledge base | Recognizing program management needs to be part of the business model and company mindset, best practice organizations invest in program management fundamentals training for their personnel to establish a knowledge base (beginning with the senior management team). |

| 4. Modify roles and responsibilities | Each organization is unique with varying roles, responsibilities, policies, procedures, and practices, not to mention culture. Transitioning to program management will require adjustment of many of the roles and responsibilities previously established for job functions. |

| 5. Create a center of excellence | Many organizations believe it is critical to create a center of excellence, which is important for gaining a foothold in the midst of change and establishing a means to sustain the change. The center of excellence is responsible for adopting and establishing a set of critical program management processes, tools, and metrics. One method for accomplishing this is through the use of a program management office (Chapter 13). |

| 6. Execute pilot programs | Program management is often implemented in waves. A roadmap for the program management transition should be established that clarifies which projects should be stopped, which will continue uninterrupted, which will be intercepted, and how new programs will be established. The piloting of the conversion of projects to programs is critical to establishing and adopting the new processes and standards (see “Pilot, Learn, Improve”). It is important to learn what works and what meets resistance before fully committing the organization to a broad-based transition. |

| 7. Institute organizational structure changes | Most organizations find a need to make adjustments to the organizational structure during the transition process. This is driven by the need to elevate the program managers and program office to a level consistent with other functions to establish authority and decision empowerment. |

| 8. Reinforce the correct behavior | As the transition continues past the piloting stages, rewards and incentives are modified to engrain desired behavior change as part of the new way of doing business. |

| 9. Set expectations for continuous improvement | The center of excellence established to provide early transition direction is rechartered to develop a roadmap for continuous improvement and to drive the implementation. |

What is a bit remarkable about this process is that it has been applied by a wide variety of companies in a number of business settings: a customer resource management software company implementing program management to provide alignment of their agile software processes to the business goals of the company, an aerospace company reestablishing program management as their basis for developing their new products after experiencing a significant number of execution failures, a start-up services company using program management to provide structure to scale its business and provide repeatable results, and a nonprofit organization implementing program management in order to manage the growing complexity of its projects.

Designing the Program Management Model

We mentioned at the start of this chapter that when organizations make the decision to cross the point of transition on the program management continuum (Chapter 1), they make the decision not only to become a program-oriented organization, but importantly they make the decision to transform their organization. Therefore, when planning for program management transition, aspects of structure, system, and culture will be at the forefront. Each is connected and affects the other relative to program management design. This is illustrated in Figure 12.1.

Figure 12.1 Elements of program management design.

Program Management Structure

Utilizing program management to create new capabilities for an organization involves the combined efforts of many personnel across an organization who work together to perform the tremendous number of activities and tasks necessary. This combined effort requires effective communication, coordination, ability to resolve issues and barriers, and effective decision making both within the team and by senior management. An organizational structure that supports and facilitates this collaborative approach is necessary.

Traditional organizational structures range from a purely functional structure to a purely project-oriented structure. Both extremes create some significant limitations from the perspective of program management. The purely project-oriented approach minimizes the critical importance played by functional managers in providing for the long-term viability of the functional capabilities by staying current on the latest technology and maintaining the highest-skilled and best-trained resources to support the enterprise. A purely functional organization minimizes the importance of cross-discipline knowledge and a systematic view needed for programs. Functional organizations tend to limit cross-discipline thinking, with authority resting only with the functional managers. As Christopher Meyer, author of Fast Cycle Time, stated, “By far, the most serious problem with the functional structure is that it serves its members better than its customers.”7

The most effective organizational structures for the program management model is a compromise between the two extremes—the matrix structure and the program structure. With both approaches, formal responsibility and authority for the program resides with the program manager.

The Matrix Structure

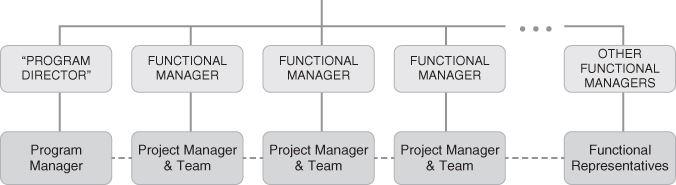

Figure 12.2 illustrates one form of the matrix structure that is used in various companies, but there are, of course, many variations of the matrix structure that can be implemented.

Figure 12.2 Example of a matrix structure for program management.

In a matrix structure, program team members continue to report directly into their functional organization (depicted as solid lines) and are loaned to the program manager (depicted as dotted lines). The program manager is responsible for integrating the cross-discipline contributions. The functional managers are responsible for overseeing the core capabilities, processes, and tools within the function.8

Like all structures, matrix management has its pros and cons. The strengths of the matrix structure are considerable and include the following:9

- The program manager has access to the entire pool of experts within the functional organizations.

- Duplication of functional departments is eliminated, with a single organization for each function.

- Resources can be shared intelligently across programs to ensure effective use of critical and scarce skills.

- Integration of the functional disciplines is enhanced, which serves to reduce power struggles and improve collaborative teamwork.

The Program Organization Structure

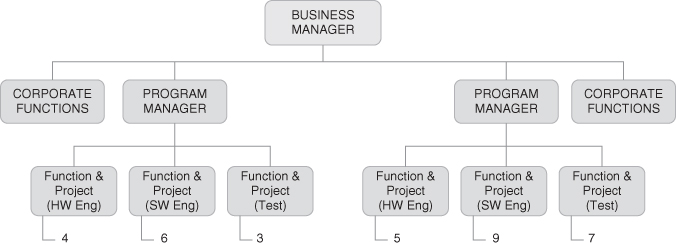

The second organizational structure that we will discuss is the program organization structure shown in Figure 12.3. This structure comes in many forms and is found in industries such as aerospace, defense, and automotive.

Figure 12.3 Example of the program organization structure.

In the program organization structure, the project teams report directly to the program manager. Whether functional managers report directly to the program manager is specific to the organization. All resources reporting to the program manager are dedicated to and work full-time on their programs. Generally, cross-program functions such as marketing, finance, and human resources support all programs, and therefore are not dedicated to a single program.

Strengths of the program organization structure include the following:

- The program manager is in direct control of all resources on the program.

- Resources are completely focused on a single program, which leads to improved productivity and cycle time.

- A high degree of cross-project integration occurs.

- A high level of program identification and team cohesion emerges.

An important element in both organizational structures is that program management is a stand-alone function. This is important to the program management model because the positive impact of program management is considerably diluted when it is contained within an existing functional organization.

Program Management Systems

When transitioning to program management, multiple systems need to be considered and modified as needed. First, program management needs to be integrated into the business and operational systems of the company as described in the integrated management system (Chapter 3). Most important is that there is systematic alignment among business strategy, the portfolio management process, and program management practices. One of the biggest transitions for any company making the transition to program management will be a restructuring of the portfolio from a set of independent projects to a set of programs with constituent projects. Additionally, relative to the operational system, alignment between business benefits, program objectives, and project performance indicators has to be established and managed for each program.

Program management transition will also bring a change in core practices, processes, tools, and metrics as described in earlier chapters. In some cases the change will be primarily an up-level or abstraction from a project level to a program level, such as in the case of risk management. In other cases new practices, processes, tools, and metrics will need to be developed and instituted as in the case of business benefits management. It is important to note that we have seen companies consistently struggle with transitioning their metrics system. Generally, firms put more emphasis on the transition of practices, processes, and tools, but seem to want to hold on to their existing set of measures and metrics. As practices change, so too must the system of metrics supporting the practices.

As indicated earlier, a company's system of roles and responsibilities will also most likely change as a result of a transition to program management. This is due to the fact that the role of the program manager is being inserted into the organization, or it is being changed to encompass aspects of other historically established roles. This realignment of roles and responsibilities can be tricky and needs to be carefully managed (see “Roles for Effective Program Management”).

Program Management Culture

The third element of the program management design (Figure 12.1), culture, consists of organizational culture, power, and beliefs. No matter what approach is taken to handle the culture element of program management, a conscious effort should be invested to purposefully design it, and not just let it evolve.

The program culture should be designed to express a set of clearly articulated, performance-oriented values and on-the-job behaviors that are built into program practices. For example, one such value is “being proactive,” in which team members practice a behavior of periodic progress reporting that includes predicting the business results, schedule, and budget at completion of their tasks. The intention is that program team members have a sense of identity with the cultural values and accept the need to invest both materially and emotionally in their program. This should make them more engaged, committed, enthusiastic, and willing to support one another in accomplishing the program goals.

Additionally, program managers should operate under a set of expected values and behaviors that are consistent with program management culture and organizational culture. Typical values and behaviors include the following:

Willingness to lead: Program managers need to take a leadership role to ensure that the viewpoints of all functions and disciplines involved with a program are considered and that work is focused toward achievement of the program vision. Willingness to lead also means being capable of quickly rewarding the team when it is doing well and also possessing the toughness required to manage through problems and conflicts.

Take ownership: Program managers need to display total ownership for the management and outcome of the program. They need to be ready to take total responsibility for their actions and the actions of their team. Additionally, program managers should champion the program within and outside of the organization.

Empower the team: Program managers must be willing to share the empowerment granted to them with the project managers on the program. Likewise, project managers must share their empowerment with their respective team members. Full team empowerment is a powerful tool for quick and effective decision making, where people closest to the issue are able to evaluate the situation and decide proper course of action.

Exhibit balance and fairness: Program managers need to exhibit balance and fairness between cross-discipline representatives on the program team. This means being able to set aside any historical bias toward or against a particular person or function that they may have had in the past. Exhibiting fairness also means setting the expectation that all others on the program team behave in the same manner. Failure to do so can foster unhealthy team dysfunction.

Be persistent: Program management is hard work. During the life of a program, the number and wide variety of problems and barriers that are encountered are enormous. The job is not for the faint of heart. It can take a tremendous amount of drive and persistence to achieve program success.

Extreme care must be taken to align program management culture with the overall company culture. As Roger Lundberg, former PMO director of the Jeep division at DaimlerChrysler explained:

There is no single right organizational solution. Each company implementing program management will have to align it with their company's culture.

If the program management design does not align with current company culture, there will be human resistance to the transition. Resistance may not only result in cultural difficulties, but to put it honestly, it may terminate the transition to program management if the resistance and cultural change are not properly managed.

Overcoming Challenges

When transitioning to a program-oriented organization, to expect there will be no challenges can be foolish, as challenges most likely will be many. From our experience and research, the most common challenges one can expect are resistance to change, tension between program management and functional management, and a misunderstanding on the part of program managers about their boundaries of authority.

Resistance to change is not unique to the transition to a program-oriented organization, as resistance arises any time a significant change to an organization occurs. One can expect resistance from both middle management and some individual contributors. A key contributor to this resistance is that any change is a change from an employee's current status quo, and most times change from status quo breeds resistance due to fear of the unknown. A company may have operated under a business model that generated good to excellent results for years; therefore, people within the organization build their comfort zones around the existing business model. However, if the current business model has run its course of effectiveness and is no longer enabling a firm to keep pace with industry changes, the business and the people it employs must either adapt to the changing environment or prepare for a potentially painful decline of their enterprise. Resistance is likely to occur more frequently and severely in the early days of the transition.

A shift in the balance of power from functional or department managers to program managers commonly leads to tension between the two groups. Many organizations transition from a functional structure in which the functional managers possess resource, budget, and decision-making power to the program management model in which budget and decision-making power shifts to the program manager. Any shift in organizational influence can cause people to react unpredictably. Christopher Meyer called this “the golden rule of organizations”—those who have the gold (in this case, the power) make the rules.10 For the program-oriented organization to work successfully, this power must be appropriately redistributed between the functional managers and the program managers by the senior leadership team of the organization. The key distinguishing point is that the program manager needs to be formally empowered by senior management to be responsible for all operational and financial aspects of their program.

Transitioning to a Program Management Office (PMO)

Many program-oriented organizations may choose to support their program management discipline by implementing a program management office (PMO). This, of course, is a major organizational change for the firm and must be appropriately planned and managed as part of the program management transition process. Businesses that have had the most success when implementing a PMO have consistently followed a comprehensive methodology as discussed earlier in this chapter.

When implementing a PMO within a company, much thought must go into how the PMO will be organized as it may have implications on current roles, responsibilities, and decision making within the organization. How the organizational elements are designed will have a large impact on the overall success or failure of the PMO as an organizational entity. There are a number of important factors that need to be considered when transitioning to a PMO including the following:

Timeline: Implementing a PMO will take time. It is not recommended that an organization attempt to establish a PMO without a transition plan in place. A logical evolutionary plan is suggested for adopting the elements of the PMO as they make sense and the organization's skill level and experience can successfully absorb the new entity.11

Centralization Philosophy: What is the firm's management philosophy regarding centralization versus decentralization of various functions and activities? Most organizations would agree on the benefit of centralizing processes, policies, tools, methods, and training. However, controversy may arise when business unit managers or functional managers are reluctant to relinquish the planning and control of programs that are directly tied to the manager's future success.

Reporting: The question as to whether all program managers should report to one person can also be controversial. This may need to be decided and resolved at the executive level. As stated earlier in the chapter, both the matrix and program organization structures work well with program managers who report directly or by dotted-line to the PMO director, while being accountable to the senior management of their business unit for the program results.

Gaining Leadership: As we discuss in Chapter 13, the selection for the PMO manager is critical. He or she will be accountable for achieving the desired business results, therefore clarity of role needs to be established as well as exercising patience to recruit and hire the right person.

Continuously Improve: The PMO must be committed to continual improvement and maturing the organization in order to remain a viable and valuable function within the organization. Long-term improvement involves capturing and innovating new best practices, evaluating and implementing more effective tools when they become available, and establishing and evolving a central knowledge base for program management. Also, as corporations continue to become more globally dispersed in their activities, the program management office must become increasingly effective in establishing and improving the linkages to the dispersed sites and closing any communication, collaboration, and operational gaps that may exist.

The Continuous Improvement Journey

Program management transition is a journey not an event. Without continuous improvement in program management practices, processes, tools, metrics, and behaviors, the program management discipline will gradually deteriorate.12 Such was the case in many of the industries that were historically strong in program management—automotive, defense, and aerospace. The disinvestment in program management and the resulting atrophy in their capabilities have resulted in mounting execution failures and missed business results in many companies. At present we are witnessing a renewed focus on rebuilding program management capabilities within these industries. Avoiding such a predicament and instead developing a continuously improved program management discipline can be achieved through a number of steps.

Forming a continuous improvement team consisting of a small number of forward-thinking individuals within the organization is necessary to gain momentum and scalability. Much of the team must come from the program management ranks. Having a program management office, even a single-person office, can provide great benefit in leading the continuous improvement team. The team must be capable of looking beyond the transition problems of today and create a roadmap for a more effective program management discipline tomorrow. The continuous improvement team must be able to focus on the critical systemic improvements needed.

Ideally, there should be a continuous stream of suggestions and ideas for improvement. One tried and true mechanism for identifying systemic improvement needs is the program retrospective.13 Establishing a consistent practice of holding retrospective reviews will lead to the identification of many of the improvements needed. Best practice companies in this area not only perform retrospectives at the end of a program, but throughout the program cycle. Other mechanisms for collecting improvement needs include direct program team feedback through surveys, focus groups, and one-on-one discussions. Additionally, sharing best practices with other companies has proven helpful for many program-oriented organizations.

Execution of the improvements should be approved by the program governance body, and then implemented within the organization and on targeted programs in a methodical manner. Improvements should be implemented as quickly as possible to reap benefits, but care must be taken to prevent more change than the organization is able to absorb at any one time.

David Churchill, former VP and General Manager at Agilent Technologies, described what he believes to be the critical factors in successfully transitioning an organization to program management:

Organizations that succeed in transitioning to program management will do the following: Treat program management as a critical talent and skill set and establish it as a functional discipline like engineering and marketing; elevate the program management function in stature and place it at the senior level in order to provide program managers the necessary level of influence across and organization; and empower program managers as leaders within the organization with sufficient authority to implement and achieve the intended business objectives.