Appendix A

“I AM the PMO!”

It is a trend that is on the rise, Program Management Offices (PMOs) that are initiated and led by individuals who single-handedly champion and grow the program management discipline within their organization. This is the story of one such leader, Ron Jacobsen, who demonstrated that a one-person PMO can become a value-contributor to an enterprise through the combination of knowledge, drive, and determination.

A Competency Lost

The company highlighted in this story is a large, multi-national enterprise that provides advanced system integration prowess and a broad product portfolio to military, federal, and civil service customers.

During the first decade of the new millennium the company expanded its capabilities and offerings to meet the rapid growth in defense spending through a number of strategic acquisitions. However, each newly acquired company brought its own business systems, processes, and procedures that represented their local knowledge and were minimally documented. Decentralization was emphasized and inconsistencies in the management of programs emerged across the company. Some of the larger programs were experiencing above-plan costs and schedule delays, yet were still achieving consistent levels of customer satisfaction due to the superior technical expertise and customer service provided by the company.

One of the business units within the company experienced a significant clash of cultures as a result of the company's merger and acquisition activities. One of the merged corporations placed significant emphasis on processes, procedures, and training of its employees in program management, while the other company retained its strong engineering orientation. At the end of the acquisition process, the integrated company no longer placed the same emphasis on program management as a true discipline and function of the organization. Program management oversight was relegated to a voluntary council, which was largely ineffective because it was starved of both authority and budget. Council representatives were provided by the business areas as an additional duty rather than a priority, and their engagement was sporadic as dictated by the demands of their programs.

However, an abundant defense budget promoted a business environment where orders and sales grew at a rapid pace. Engineering managers and project leaders were promoted into program management roles based on their achievements as engineers, but were not trained in program management. As a result, programs were run as projects and were not meeting the business performance measures such as cash flow and profit margins. Program planning, if any, was the minimum required by contract. Risk management was loosely practiced and mainly by engineering. Estimates, when completed, were inaccurate, and financial performance was below plan.

Lines of responsibility, accountability, and authority had also become blurred. The environment encouraged customer intimacy where the program manager's role was largely outwardly facing. Program management processes were considered too administratively burdensome and an unnecessary cost. Project leaders ran the programs and engineering managers had significant influence on the direction of the programs. All of this led to conflicting roles between program managers and project leaders as well as higher levels of management in customer communication and contact. Long-term strategic planning became overly optimistic based on the varying views of the program manager and the levels of management above. Business planning was inaccurate and programs were not achieving their annual goals and objectives because program execution primarily remained technically focused. In short, the focus was on winning business in a low-margin, highly competitive industry.

After a number of years managing confusion, the leadership team recommended a renewed focus on program management and the establishment of a program management office to the senior executive of the business.

“Welcome to the Company”

The business leaders decided to reinstitute program management under a new model based upon the senior executive's belief that program managers' skills and behaviors must include business acumen, strategic focus, and solid leadership. He believed these skills were an integral part of the program manager's behavior that was not currently demonstrated in their business unit. The direction of any program requires a plan that provides a balanced, strategic approach between the customer's requirements, technological advances, and the needs of the business to realize its return. The program managers within the organization needed to understand why they owned a “business” within the business.

There was consensus among the leadership team that there was a need for a strong PMO manager who could implement this new model, and that this position had to be created with equal footing to the business unit directors to emphasize the importance of program management.

They also believed that the PMO had to be part of the senior management team at a level comparable to other critical functions such as finance, engineering, and operations. The reasons for this were:

- It establishes program management as a true function on par with the other key functions in the organization.

- It provides alignment between business strategy and program execution, consistency in business results across the programs, and development of program management competencies and career path.

- The PMO must have sufficient political and decision-making influence to broker tensions between functions.

- Increased emphasis on program management addresses two common business needs: 1) consistency in definition, planning, and execution of all programs, and 2) the need for a single program point-of-contact and accountability that provides improved communication, decision making, and program oversight.

The precise roles and responsibilities were loosely defined to enable recruiting of the right individual with a proven record of accomplishments and in-depth knowledge of program management processes. The person selected for this role needed to understand the program management discipline through direct experience as a program manager. The experience gained by leading programs of significant size and complexity was necessary to understand the range of programs in the company's portfolio. A proven track record of leading highly technical, integrated programs while achieving cost, schedule, and other program objectives had to be evident. The PMO Manager role was defined as:

- Measuring overall success of programs and their ability to meet business objectives.

- Focusing on consistency of methods, tools, metrics, and practices across all programs and projects.

- Defining program metrics to ensure programs are meeting business objectives.

- Developing and administering a career ladder for growth and advancement of program managers in conjunction with human resources and the other business directors.

- Being the focal point for competency building and providing a learning environment for alignment of leadership, philosophies, and practices.

- Continuing the improvement and maturity of people, processes, and practices by capturing best practices, tools, and metrics.

- Establishing and evolving a central knowledge base for program management.

The company found who they were looking for in Ron Jacobsen. Jacobsen spent 27 years with a large corporation in the aerospace industry where he managed three international programs over a ten-year span. During this time, Jacobsen experienced the implementation of an executive PMO and evolution of the company's program management processes. Jacobsen also served on the steering committee for those processes and taught program management courses to program managers and other company personnel.

Understanding the Landscape

Jacobsen began his new role by understanding the current state of program management competency within his new company. The existing procedures were read, program reviews were attended, and the work of the program management council was assessed. He found that a comprehensive training curriculum was published; however, little budget was provided to actually conduct the training. Small pockets of coaching and mentoring based on self-assessed competencies were evident throughout the organization, but company-paid professional development was provided on a limited basis only, due to the minimal available budget.

Jacobsen then interviewed senior management, engineering and functional organization managers, and program managers to understand the nature of the environment. The consistent messages that came out of the interviews were:

- Program managers were not intimately familiar with the customer's requirements, budgeting cycles, or engineering change proposal process.

- Programs did not consistently identify risks and opportunities or include them in the estimate at completion.

- Subcontracting was unquestionably everyone's “hot button.”

- A need existed for a more structured program management approach, a set of tools, and a management council to govern program management.

- There did not appear to be a baseline of program management skills.

- Program communication was critical but there were conflicting ideas on how to communicate effectively.

- New programs tended to be scattered in the early phase but got better with time.

- Uncertainty of the various levels of responsibility, authority, and accountability for a program manager was prevalent.

Establishing “Street Cred”

The assessment of the priorities of what needed to be improved and where to start had to entail buy-in by everyone involved (program managers, the functional organizations, and the management chain). Since there was to be no PMO support staff, everyone had to share a common goal to improve the collective program management skills and abilities. However, few completely understood the role of a PMO even though there had been plenty of briefings and one-on-one meetings with the program managers in multiple geographic locations. The social attitude of “not invented here, won't work here” became evident quickly. A number of times comments such as, “We're not the company you came from” or “We're not an airplane” or “The processes don't fit the size and complexity of programs we have” were voiced. Establishing credibility with senior management and the organization's program managers was vital since Jacobsen and the PMO were new to the company and the business unit.

Shortly after joining the organization, Jacobsen demonstrated the power of program management by guiding the recovery of a program for which he had no product or customer knowledge related to this company. His success was based purely upon the reliance of thorough application of the program management discipline. Concurrent with this, he met with all program managers to explain the PMO role and vision and got their input into what made their jobs difficult. His review of procedures determined they were adequate to give a general idea of what a program manager was supposed to do. He attended program reviews to get more insight into the culture and how effectively program managers communicated program execution.

Creating a Transformation Plan

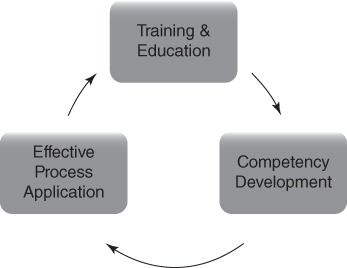

Jacobsen began to establish a vision for transforming the organization based upon the executive manager's belief in the need for a strong program management capability. The vision would be based on several factors. First, the establishment of common program management processes would be required, and then understanding and applying those processes effectively would require training and education. Once trained, a program manager's competence could be measured in the effective application of those processes toward managing a program and delivering positive business results. Further development of the program manager could then be supported by additional training and education or an assignment to another program for career development. This iterative approach is displayed in the figure below.

Figure A.1 A vision for building program management competency.

Jacobsen then developed and proposed a three-year transformation plan that was based on defining the job, teaching it, setting expectations for it to be followed, and measuring improvement in program execution. The primary elements of the three-year transformation plan were as follows:

Year One: Establishing the program management model

- Define the program management model and align existing procedures to it while identifying gaps or needs for new or updated procedures.

- Review and prescribe policies, procedures, tools, and metrics with functional process owners as subject matter experts paired with a program manager to ensure alignment and understanding.

- Determine application of processes, metrics, and tools appropriate to program size and category.

- Develop and publish “Knowledge Area Guide Sheets” with the above information as a starting point and continuing reference.

- Develop and conduct training to implement program management processes, tools, and metrics.

- Establish a cross-business view to optimize program manager assignments across programs through effective workforce planning.

Year Two: Positioning program management for the long term

- Overcome remaining resistance to program management acceptance.

- Continue improving program planning, execution, and control.

- Maintain excellence in customer intimacy.

- Validate program management processes and rectify gaps in or need for new ones.

- Continue the cross-business view to optimize program manager assignments across programs through effective workforce planning.

- Continue program management training in greater detail on processes and financial acumen.

Year Three: Establish program management as the business foundation

- Measure effectiveness of program planning, execution, and control.

- Grade each program's implementation of program management processes and tools.

- Adopt best practices for process improvements.

- Establish a complexity model used to determine application of processes, metrics, and tools appropriate for the level of program complexity.

- Begin filling the talent funnel with high potential junior program managers.

The transformation plan was approved by the leadership team and then rolled out to the program managers. A budget for training was estimated and approved by the executive sponsor—a sign that he was solidly behind the plan.

Defining the right program management model to be implemented at the beginning of year one would require substantial effort. In response, Jacobsen established a three-phase approach (Table A.1).

Table A.1 Three-phase approach for year one transition

| Phase | Critical Transition Steps |

| Phase One | Size and define program categories. Define processes and align existing procedures or identify new ones. Review and prescribe program tools and metrics. Determine application of processes, metrics, and tools appropriate to program size. |

| Phase Two | Conduct two days of pre-requisite training to level-set and orient program managers in achieving successful business results through effective program management. Require training in processes, tools, and metrics and set expectations for performance through an interactive three-day workshop. |

| Phase Three | Finalize all elements of the transformation plan and measure implementation effectiveness. |

Phase I proved the most daunting considering Jacobsen did not have the domain knowledge of the range of products offered by his new company. His domain knowledge was aerospace program management and processes. He forged his expertise in the former domain by successfully managing three complex programs in an environment where processes were to be followed with discipline. It was eventually defined that there were four common denominators to any program regardless of its size, complexity, or company:

- It has to have a plan—plan your work, work your plan.

- Baseline management is critical—establish them, manage to them, and control change to them.

- Risk and opportunity management are needed—zealously drive out cost, schedule, and technical risks and exploit any and all opportunities where there is a derived benefit to the program and customer at a reasonable cost.

- Deliver positive financial results—to the company and to the shareholders.

There were numerous challenges that defined the boundary conditions in establishing the program management model and the PMO. First, senior management decided that the PMO would not have any staff personnel supporting Jacobsen. Second, a large number of new procedures could not be generated to prevent an administratively burdensome and rigid environment that would increase program costs. Third, what was to be implemented had to fit the range of programs in the portfolio.

Jacobsen decided to use a participative approach to get buy-in across the organization and become part of the solution through the development of his plan.

Generating Results

Two of the main criteria used for measuring the effects of the new program management model and PMO were the number of “Yellow” or “Red” programs (those experiencing critical implementation issues) within the business unit's portfolio and the value of operating margin for each program. Once the PMO was fully operational, the business unit became the only one that no longer had “Red” or “Yellow” programs. Also, a gain in its overall adjusted operating margin from 9.4 to 11.9 percent was experienced within the first three years.

Additionally, the PMO began to experience intangible results such as requests for Jacobsen's program managers to assist programs in other business units, getting consistency of results from the program managers, having a common understanding of program management processes, and the ability to move program managers between programs to adjust to the changing business conditions.

Keys to Success

Establishing credibility with senior management was paramount to the plan's success. Jacobsen had a supportive senior management champion whose endorsement was demonstrated early on during a “town hall” meeting in which he rolled out the PMO purpose, roles, and relationships on the part of the leadership team, and Jacobsen's three-year transformation plan. He also reiterated his endorsement frequently at business plan reviews and other meetings.

However, the sponsor could have provided further endorsement and empowerment of the PMO role by rejecting demands that the PMO prove it was adding value as an overhead function. Overhead, it was decided, was the best way to spread the cost evenly across the organization. There is a perception that PMOs are viewed as a cost contributor and not a direct revenue producer. But, that perception overlooks the direct leadership provided to all programs under the PMO's responsibility that are driving revenue-generating results.

Other critical factors for success identified were obtaining program manager feedback on required revisions to the procedures and processes as an indication to the program managers they were being listened to and were indeed part of the solution. Revising the monthly program review to a standardized format and instructing the program managers on what the data should tell them was a critical milestone. The monthly cost, schedule, and technical status provided indication that the quality of the program manager's knowledge was improving as was the implementation of program management processes across the board.

Ultimately, though, a large share of the credit for the improvements seen in the business unit belongs to the professional program managers who accepted the model as the change needed to enhance their skills and abilities and run their programs more effectively.

Jacobsen's three-year program management transformation plan is currently nearing completion and is being “moved upstairs.” It is in the process of being expanded to the rest of the company along with Jacobsen, whose contributions have been recognized by senior management. Jacobsen now has the president of the company and the executive leadership team as sponsors.

The Office of Program Management (Jacobsen's new role and responsibility) now heads up the Program Management Council which is made up of other business units' PMOs and functional representatives. The Council now has the “teeth” to implement process and procedural changes across the enterprise as well as assess and coordinate changes in subperforming programs to improve performance. Jacobsen spends most of his time with mid-level managers explaining and reinforcing the PMO role and the resources that can be brought to bear through independent assessment and intervention on any program.

The three accomplishments that Jacobsen values most are turning a skeptical group of former engineers into professional program managers, demonstrating the effectiveness of program management processes regardless of size and complexity, and achieving business results with them!