Case 7

Facing Reputational Risk on Goldman’s ABACUS 2007-AC1

Rosenblum thinks there could be reputational risks. So, he wants us to review ABACUS 2007-AC1 with the Mortgage Capital Committee (MCC). I sort of understand. This thing is a monstrosity. Still, I’m not exactly sure what he means by ‘reputational risk’ and what difference that might make for how we construct and sell this product.

IT WAS LATE FEBRUARY, 2007. FABRICE TOURRE, a Vice President working for Goldman Sachs’ “structured products correlation trading desk” was just finishing up engagement letters for a new deal, ABACUS 2007-AC1. The deal, a Synthetic Collateralized Debt Obligation (SCDO), was rounding into shape. Tourre had defined the subprime mortgage-backed Collateralized Debt Obligations (CDOs) that the deal would reference. He had received a verbal commitment from ACA Management LLC (ACA) to act as the “portfolio selection agent.” Tourre had calculated that ABACUS 2007-AC1 would earn Goldman Sachs $15–20 million dollars with the firm taking little risk. Everything was falling into place.

To make sure that all bases were covered, Tourre asked David Rosenblum, one of his bosses, whether the deal needed to go to the MCC. Rosenblum said that it did. Then he had added a comment that reputational risk for Goldman was the reason for holding the review.1

Rosenblum’s comment stirred up doubts that had festered inside Tourre since the deal was broached. ABACUS 2007-AC1 had developed in an unusual fashion. The deal had been suggested by John Paulson, a hedge fund manager. Paulson had been “shorting” the subprime mortgage-backed security market since mid-2006. Then in December, Paulson asked Goldman to construct a $2 billion SCDO—where Paulson would be taking the “short” side of the trade. This meant that Paulson would be using the SCDO to make a very large bet that the subprime CDO market was going to collapse. Paulson’s bet would only pay off if mortgage CDO prices collapsed and/or the underlying mortgages went into default. Paulson also had very specific ideas about how this SCDO should be constructed. He had given Tourre a list of over 100 BBB-rated residential mortgage-backed securities (RMBS) which he thought might encounter problems.2 Paulson wanted Goldman to reference these bonds when it constructed the SCDO. Goldman would then market the deal under its ABACUS label to institutional investors willing to bet that the referenced bonds would pay off as planned.

Other aspects of SCDOs bothered Tourre. For one thing, he thought that they served no fundamental economic purpose. For another, he was uneasy about selling more of these securities to investors at a time when the mortgage market seemed headed for a crash. He put these concerns into e-mails to his girlfriend, who worked for Goldman in London, writing:

“More and more leverage in the system … the entire system is about to crumble at any moment …3

[I’m] standing in the middle of all these complex, highly levered, exotic trades [I] created without necessarily understanding all the implications of those monstruosities [sic]!!! …

When I think that I had some input into the creation of this product (… the type of thing which you invent telling yourself: ‘Well, what if we created a “thing,” which has no purpose, which is absolutely conceptual and highly theoretical and which nobody knows how to price?’) [I]t sickens the heart to see it shot down in mid-flight … it’s a little like Frankenstein turning against his own inventor …”4

Tourre had a sense, however, that Rosenblum had something else in mind when he brought up reputational risk. Goldman had constructed many SCDOs using its ABACUS platform. The firm was well past having fundamental doubts about this class of securities. Tourre began to ruminate on what particular concerns Rosenblum might have. If Tourre could get a fix on those issues, he could address them upfront in his MCC presentation.

One possibility concerned the fact that Goldman would be selling the SCDOs to investors at the same time that it had reached the same conclusions as Paulson. Consequently, it had been reducing its exposure. Most recently, Goldman had moved beyond cutting exposure to betting that the subprime mortgage market would collapse. The traders called it “the big short.” With the firm betting its own money in this way, could Goldman market ABACUS 2007-AC1 to clients as if it believed the SCDOs were a sound investment?

Another possible issue concerned Paulson’s involvement. It was not uncommon for investors to ask Goldman to construct a CDO. Sometimes they even recommended securities to be included. Usually, however, the investors were taking a long position, i.e., betting that the CDO securities were going to perform well. Paulson was betting they were going to implode. Did that change the correctness of having him select the referenced portfolio?

Tourre could reach no firm conclusions. Before preparing his MCC presentation, he decided to review the deal’s history. Perhaps that would give him a better handle on what reputational risks Goldman might be running with ABACUS 2007-AC1.

From Subprime RMBS to CDOs to SCDOs

To appreciate Tourre’s concerns that SCDOs were unfathomable instruments without economic purpose, one had to understand the history of how subprime RMBS begot CDOs, which in turn led to Synthetic CDOS.

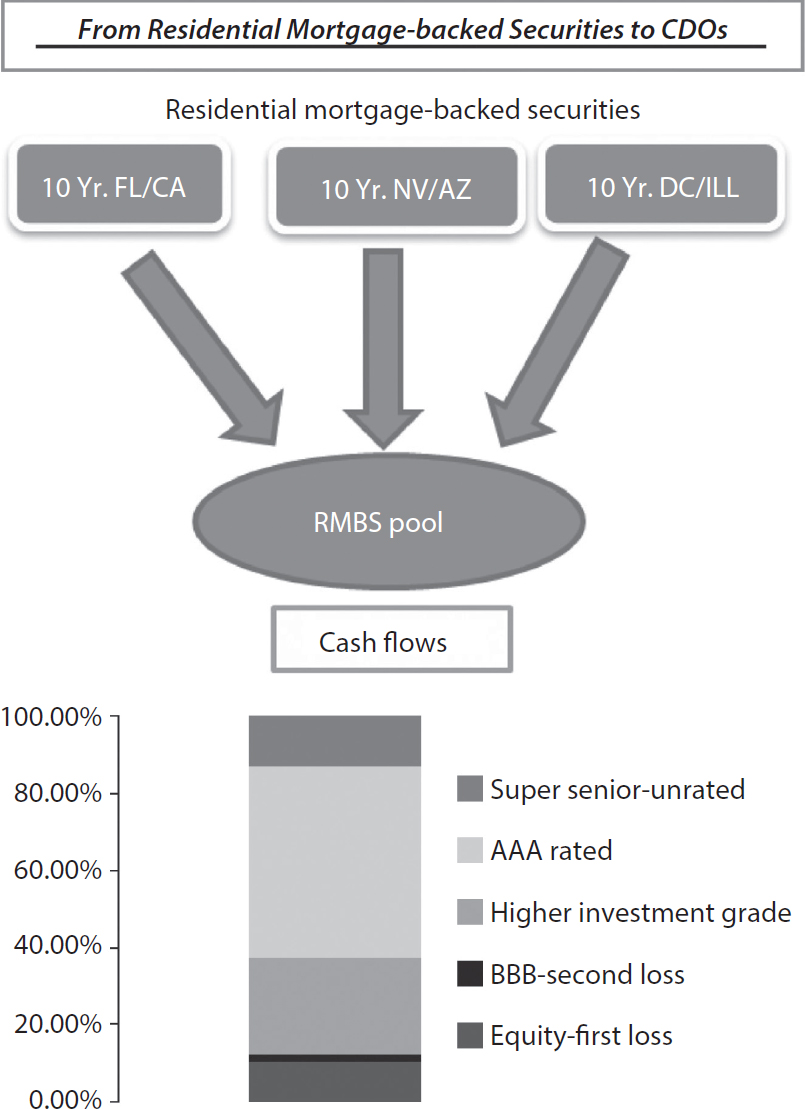

RMBS were first constructed in the 1980s. First Boston and Salomon Brothers pioneered their creation and marketing. RMBS are created by pooling a large number of mortgages and then carving out from this pool cash flows that resemble the interest and principal payments of a bond. First Boston’s creative contribution was to tranche the securities, so that a given pool of mortgages would be carved into cash flows resembling bonds with different maturities, e.g., 5-year, 10-year and 30-year bonds. Securities with these maturities, backed by the cash flows from the respective assigned mortgages, could then be marketed to investors. As a later enhancement, the mortgages being pooled were taken from different real estate markets, e.g., Atlanta, Los Angeles, Washington D.C. This provided risk diversification and improved credit ratings.

CDOs were developed in the 1990s. By this time there were large amounts of RMBS outstanding. Whereas RMBS allowed investors to express their preferences for different maturity instruments, CDOs allowed them to choose among risk/return options. By pooling sufficient RMBS, flows resembling large amounts of bonds could be created. Diversification was again employed to improve credit quality; in this instance the underlying RMBS were based on mortgages concentrated in different property markets.

Another Wall Street’s innovation was to introduce “subordination” into the picture. CDOs also involve tranches, but in this instance the tiers reflect different exposure to credit losses. At the bottom of the CDO is the unrated equity tranche. Any losses experienced from the underlying RMBS pool go first against this tranche. Typically, the equity tranche amounts to about 8% of the total value of the underlying RMBS. Sitting atop the equity tranche is the low investment grade, or mezzanine tranche. Usually rated BB or BBB, this tranche takes losses only if defaults on the underlying RMBS completely wipe out the equity. The mezzanine trance normally represents 2% of the underlying RMBS.5

In Goldman’s experience, tranches above the mezzanine obtained higher investment grade ratings. Normally more than 50% of the remainder would receive AAA ratings. Typically, there was also a “super-senior” tranche that was considered so insulated from losses that underwriters didn’t bother to get it rated. Returns on these different tranches reflected the ratings; super-senior trances, for example, might be priced at only 20–30 basis points (.2–.3%) above U.S. Treasury securities.

Synthetic CDOs came into being in 2003–04. They were made possible by another instrument, the Credit Default Swap (CDS). A CDS is a contract under which two parties agree to make certain payments contingent on events. The party taking the “long” side of the contract promises to pay if certain credit events occur. To give an example, consider the writing of a CDS on a conventional corporate bond. In this case the long party is committing to pay the counterparty any interest and principal payments which the obligor on the bond fails to pay. In return for writing this protection, the short party pays the long counterparty an annual fee—which resembles the risk premium on the underlying bond. Like bonds, CDS contracts can be traded. Their prices and implied credit spreads fluctuate, providing an up-to-date reading on how markets are pricing the credit of an obligor.

Tourre recognized that CDS contracts have a variety of uses. A primary use is to hedge credit risk. Creditors can reduce existing exposures by entering into CDS contracts in which they take the short side. However, CDS contracts also make a highly leveraged speculative vehicle. This is possible because CDS contracts do not require any party to have an “insurable interest,” i.e., an underlying exposure that it seeks to hedge. So long as some counterparty is available in the market, any party can decide to bet on the creditworthiness of another entity. The bet is highly leveraged for the short side, as the payoff can be massive relative to the amount of fees paid to the long. As for the “longs,” most expect a steady stream of payments for which they will pay out nothing at all.

Wall Street eventually realized that CDS contracts could be used in connection with mortgage CDOs. An intermediary, the investment bank or a portfolio selection adviser, would identify CDO tranches to reference. This meant that the counterparties to the CDS contract were betting on this pool’s performance. The credit events were defined for each Synthetic CDO deal; they could be security price declines of some magnitude of credit downgrades, payment delinquencies, or some combination. Because the SCDO was based on a CDS, it could serve as a hedge instrument. Parties wanting to reduce their exposure to mortgage CDOs could write the short side of the SCDO. However, Tourre knew that the SCDO was also a jet-propelled trading vehicle for speculators and Wall Street firms. They did not have to originate mortgages or buy CDOs to make almost unlimited bets on mortgage-backed bonds.

Attachments 1–3 illustrate how mortgages were packaged into RMBS, how RMBS were compiled into CDOs, and how the adaptation of the CDS contract produced the synthetic mortgage-backed CDO. The diagrams help emphasize the dramatic separation of the SCDO CDS contract from the underlying mortgages. The SCDO long party writing the protection is now referencing thousands of mortgages from multiple states, on which it has done no direct due diligence. Consequently, the long party’s reliance on the RMBS and CDO ratings issued by the rating agencies is near total. Tourre reflected on these facts, thinking them the reasons why SCDOs were not easy for even sophisticated investors to understand or price.

Tourre thought that one more instrument, the ABX index, deserved his attention. As the subprime mortgage securities market expanded, traders began looking for a way to measure and bet on its risk. An index was developed which referenced 20 outstanding subprime RMBS. Hedgers and speculators could then either buy or sell this index. If the index increased in price, that implied a market perception of lower risk in the underlying bonds. A fall in ABX price implied the opposite, higher risk.

All of these instruments enabled Wall Street firms to construct complicated trades associated with underlying business. Firms bullish on the subprime market could originate mortgages, underwrite RMBS and CDOs, and go long on SCDOs or the ABX. Firms with more concerns about the market could still engage in the first two activities, harvesting good fees as intermediaries. They then could hedge their warehouse and inventory positions by shorting SCDOs and the ABX index. The index also helped firms to construct the kind of transaction Tourre was contemplating. For instance, to put the ABACUS deal together, Goldman might have to go long on part of the transaction. It could then choose to offset this position by “shorting” the ABX. Depending upon its final configuration, Goldman could end up as an intermediary, an investor, a hedger, a speculator or all of the above. Would its ultimate positions on this deal be in conflict?

To make sense out of these possibilities, Goldman needed excellent information systems, a strong risk management culture, and the ability to manage conflicts of interest. Tourre turned next to reviewing these matters.

Goldman’s Trading and its Clients, 2006–07

Perhaps unique among Wall Street investment banks, Goldman had both strong systems and risk management. Goldman employees working in control or financial reporting were not second-class citizens. David Viniar, Goldman’s CFO, was a political force to be reckoned with. Each day he reviewed the results of Goldman’s fifty-plus business lines. A word from Viniar could cause trading positions to be changed overnight. Goldman’s risk management committee met weekly, and included CEO Blankfein and President Gary Cohn. Both routinely examined Goldman’s exposures and inserted themselves into their management.6

Goldman also invested in proprietary systems that allowed management to examine daily positions down to the individual securities. Goldman also had systems which allowed it to revalue security holdings under downside scenarios. Most Wall Street firms where content to know their “Value at Risk” (VAR). This measure told them how much might be lost in one day under “conventional wisdom” downside assumptions. Real “Black Swan” downside cases were seldom examined.

In mid-2006 a Goldman trader, Josh Birnbaum, noticed John Paulson making big ABX short bets. Birnbaum met with Paulson to gauge the reasons underlying his risky bet against the subprime market. Birnbaum came away impressed with Paulson’s logic. At the same time, one of Birnbaum’s analysts used a Goldman system to show how easily the BBB tranche of a subprime CDO might be wiped out. The analyst found that a powerful nonlinearity was at work. If a given CDO suffered losses of 8% or less, the equity tranche would be impacted but the mezzanine tranche would pay out 100%. However, if losses increased by another 1%, to 9% total, the BBB tranche would lose 50% of its value. At 10% losses it would be wiped out. Birnbaum looked at these results and concluded that the market was completely mispricing the mezzanine tranches. To a lesser extent, it also was mispricing the higher rated securities.7

Taking into account this new insight, his conversation with Paulson, and increasing evidence of mortgage defaults, Birnbaum began to take “short” mortgage positions. Throughout the fall of 2006, he and other Goldman traders sold off long positions, bought CDS protection on outstanding subprime CDOs and shorted the ABX index.

This drive to get “closer to home” (net zero subprime mortgage exposure) accelerated in December. By the middle of that month, CFO Viniar observed that Goldman’s mortgage desk had lost money for 10 consecutive days. Viniar concluded this was a trading anomaly; even in bad markets normal trading activity will generally interrupt downward price trends with technical rallies. Viniar concluded that something unusual was disturbing the market. Viniar was also hearing from Daniel Sparks, head of Goldman’s 400 person mortgage trading department. Sparks told Viniar that hedge funds were dumping subprime securities back onto Wall Street. He also said that mortgage originators like New Century were not honoring “take-back commitments” on mortgages that went bad before they could be securitized. Sparks wanted Goldman to get the firm’s subprime risk down right away. At a December 14 meeting of Viniar and the major trading desks, Goldman decided to do just that.8

By the time Paulson approached them on the ABACUS deal, Goldman was rapidly reducing its subprime exposure. Within three days of the December 14 meeting, Goldman had eliminated $1.5 billion of exposure to BBB-rated subprime securities. There was at least another $1 billion to eliminate before Goldman could go net short. Throughout the rest of December and into January, Goldman considered all its options for getting shorter. These included selling off mortgage securities in inventory, selling off new CDOs, buying CDS short positions, and selling the ABX index. By the end of the month Goldman resolved to do all of the above. Birnbaum was authorized to put on “the big short.”9 Goldman was not going to stop at zero exposure. It was going to bet the firm’s capital in a big way that the subprime market was going to collapse.

This backstory complicated Tourre’s thinking about ABACUS and Goldman’s reputational risk. In theory the ABACUS deal was a straight intermediation—Goldman was standing between Paulson and the long investors, helping to build a security, and then selling it to willing customers. The likely buyers were big boys, institutional buyers familiar with how SCDOs worked. That said, Tourre was picking the securities based on the recommendations of a hedge fund manager poised to bet those same securities would fail. Moreover, his own firm agreed with Paulson and would be “mirroring” Paulson’s bet. What did those facts mean for the marketing of ABACUS 2007-AC1? What, if anything, did Goldman owe to its buy-side clients as regards Goldman’s views on the subprime market or the securities embedded in the ABACUS deal?

Precisely these types of conflicts had led Goldman managers to discuss the increasing complexities of the firm’s client relationships. How was Goldman supposed to manage relations with clients who, from one moment to the next, might be M&A advisees, buyers of underwritten bonds, and sellers of CDS protection?

Tourre decided that perhaps his meeting with the MCC was intended to sort out exactly these complexities. If so, the committee would need to review the construction and marketing of the ABACUS deal.

Fabrice Tourre Constructs ABACUS 2007-AC1

Tourre next reviewed his notes and documentation regarding Paulson’s involvement.

Late in 2006 Paulson had sent Goldman a list of over 100 BBB-rated RMBS which he wished to see included in the ABACUS transaction. These securities included a high percentage of adjustable rate mortgages and borrowers with low credit (FICO) scores. The mortgages were concentrated in California, Nevada, Arizona and Florida. These states had all experienced substantial home price appreciation that was starting to unravel. Paulson informed Goldman he wanted the ABACUS deal to reference these bonds or securities with similar characteristics. The list was forwarded to Tourre who was tasked with constructing the SCDO.9

Tourre next contacted Laura Schwartz, a senior managing director at ACA, asking if that firm would act as the deal’s portfolio selection agent.10

On January 9, 2007, Tourre and Schwartz met with Paulson’s representative at Paulson’s office. They discussed the securities Paulson had recommended for inclusion in the SCDO. The next day Tourre sent ACA an e-mail discussing its role as portfolio selection agent. The e-mail described Paulson as the “Transaction Sponsor” and read in part: “starting portfolio would be what the Transaction Sponsor shared but there is flexibility around the names.”11

At the same meeting Schwartz inquired about Paulson’s investment plans within the deal. In his subsequent e-mail, after naming Paulson the Transaction Sponsor, Tourre described a deal capital structure; this structure included a 0–9% first loss equity position. ACA inferred from this that Paulson intended to purchase this equity position. Despite subsequent inquiries and evidence that ACA believed Paulson was buying the equity tranche, Tourre and Goldman did not disabuse ACA of its misperception.12

On January 22 ACA e-mailed Tourre with a list of 86 RMBS to be included in the SCDO. This list included 55 of Paulson’s originally recommended bonds. ACA, Tourre and Paulson’s representative then met at Paulson’s office on February 2. During the meeting Tourre e-mailed a Goldman colleague, saying “I am at this ACA/Paulson meeting. This is surreal.” The meeting ended with the parties agreeing on 82 RMBS for the SCDO plus 21 replacement securities. In a February 5 e-mail to ACA, with a copy to Tourre, Paulson deleted 8 bonds, approved the rest and indicated to Tourre he thought a 92 bond portfolio was adequate.13

On February 26, ACA and Paulson finalized agreement on a 90 bond portfolio for ABACUS 2007-AC1.14 On the same date Tourre finalized the preliminary marketing brochure for the deal. It described ACA as having selected the referenced bond portfolio and gave extensive background on the firm’s history as a portfolio selection agent. The materials also indicated that the party selecting the portfolio had an “alignment of interests with investors.” No mention was made of Paulson’s role in selecting the securities or of his plans to use the transaction to further short the subprime mortgage market.15

Tourre Prepares for the MCC ABACUS Review

Tourre’s outline of his MCC presentation was already prepared (Attachment 4). He intended to highlight the structure of the deal, ACA’s intermediary role, and the earnings potential for Goldman. He would also note certain structuring innovations and the fact that the deal would enhance Goldman’s reputation for constructing complex transactions customized to meet multiple clients’ expectations.16

Tourre now turned to the issue of possible reputation risk for Goldman. ABACUS 2007-AC1 was ready to be marketed. Assuming the MCC gave its blessing, Tourre’s next task would be to find institutions willing to write a CDS on the different CDO tranches. Tourre already knew that Paulson’s fund would take the short side of the trade. Any long tranche positions not sold would end up on Goldman’s books.

Tourre was already thinking of IKB Credit Asset Management as a primary buyer of the long CDS position. IKB, a big German bank, had been a large buyer of CDOs for their investor accounts under management. In preliminary discussions IKB had indicated interest in the new ABACUS deal. The bank had, however, expressed concern regarding reports of trouble at subprime mortgage originators like New Century and Fremont.17

Tourre wondered how IKB and others might react to the news that Goldman was betting heavily against the mortgage market. Was that a material fact that needed to be disclosed? If it were disclosed, would IKB still go forward with the deal? If it were not disclosed and later came to light, would IKB and others trust Goldman’s future marketing representations? Would they continue to do business with the firm?

Wondering whether these were the reputational risks that Rosenbaum had in mind, Tourre picked up his presentation outline. He began to consider whether modifications or additional disclosures to the MCC were needed. If so, what specific changes should Tourre make?

Attachment 1

Attachment 2

Attachment 3

Attachment 4—Historical Recreation (HRC)

- New, innovative transaction with several technical “firsts.”

- Transaction is consistent with Goldman’s strategic objective—demonstrating our ability to structure and execute complicated transactions that meet the needs and objectives of multiple clients.

- Specifically, ABACUS 2007-AC1 accomplishes the following for clients:

- Enables Paulson to execute a macro hedge on the RMBS market

- Offers CDO investors an attractive product relative to other structured credit products now available

- Allows ACA to increase both assets under management and fee income

- Goldman will make $15–20 M from the deal.

- Remuneration for Goldman is compensation for acting as intermediary between John Paulson and ACA. Goldman’s role includes structuring, deal underwriting, marketing of SCDO long position, and use of the ABACUS brand.

- Basic deal structure:

- Synthetic CDO referencing portfolio of 90 subprime RMBS rated BBB

- ACA acting as portfolio selection agent

- Referenced portfolio based upon original list submitted by Paulson and modified after discussions with ACA

- Goldman will write Paulson’s fund a CDS on the referenced securities

- Goldman will then market its long CDS position to institutional investors with the objective of 100% sell down

Author’s Note

This case contemplates the consequences of Goldman Sach’s commitment to massive proprietary trading and its belief that it could manage the client conflicts associated with that business model.

Students are asked to stand in the shoes of Fabrice Tourre, a young Goldman executive, as he is asked to construct an SCDO to the specifications of John Paulson. This is a tough situation for Tourre. He lacks seniority within the firm and any convenient way to register his misgivings. Then an opportunity presents itself. One of Tourre’s bosses directs Tourre to review the deal with Mortgage Credit Committee. The boss also mentions he is concerned with “reputational risk.” Tourre now has an opening to disclose the deal’s conflicts and issues with senior management; he also can lay out his own ideas for managing them.

Attachment 4 is a key document for students. It outlines Tourre’s draft presentation to the Mortgage Credit Committee (MCC). It is a Historical Recreation based on accounts of what Tourre actually told the MCC. Students should use it as a vehicle for expressing their case solution.

The case recounts Goldman’s evolving thinking on the mortgage market and the need to hedge its own exposure. It also describes the firm’s December 2007 decision to go massively short as a P/L strategy. That Goldman does this coincidental with creating and marketing the ABACUS deal creates the client conflicts and disclosure questions that Tourre must now confront.

Source material principally comes from William D. Cohan’s excellent history of Goldman Sachs, Money and Power: How Goldman Sachs Came to Rule the World, and the SEC’s Complaint against the firm and Tourre. Cohan’s work is the source for important details, including the contents of Goldman’s conversations with John Paulson, and Tourre’s ABACUS 2007-AC1 presentation to the MCC. The SEC Complaint recounts crucial details that Tourre never disclosed to ACA: (1) that Paulson, the “transaction sponsor,” was not going to buy the equity tranche, and (2) that Paulson planned to short the deal.

Apprehensive about the “commoditization” of their historic functions, firms like Goldman cling to the “giant hedge fund” trading model. They continue to do so despite considerable evidence that it promotes insider trading and endless conflicts of interest with clients. Further legal and regulatory steps may be required before these very conflicted conditions are resolved. In the meantime, students contemplating a career with Goldman or Morgan Stanley should expect to face conflicts not unlike those which made Fabrice Tourre the target of a formal SEC action.

This leads to a final point. Tourre was the only individual targeted by the SEC’s complaint. Goldman Sachs, the firm, was targeted and paid a fine. Tourre, however, was found liable and fined more than $800,000 by the SEC. Why was Tourre the only individual so targeted? Why are none of the individuals on the MCC being held responsible? Students should remember if they ever face analogous circumstances that the firm may not hesitate to “throw them under the bus” to protect those higher up.