Chapter 13

Keeping Track of Finances

In This Chapter

![]() Keeping essential records

Keeping essential records

![]() Understanding the main accounting reports

Understanding the main accounting reports

![]() Analysing financial data

Analysing financial data

![]() Meeting profit goals

Meeting profit goals

![]() Evaluating financial performance

Evaluating financial performance

![]() Meeting legal obligations

Meeting legal obligations

Every business needs reliable financial information for both decision making and accountability. No one is going to be keen to pump money into your venture if you can’t demonstrate that you know what’s likely to happen to it. Reliable information doesn’t necessarily call for complex bookkeeping and accounting systems: simple is often best. As the business grows, and perhaps takes on outside investors, you require more sophisticated information. That’s when using a computer and some of the relevant software packages may be the best way forward. But even with a computer errors can occur, so you have to know how to recognise when financial information goes wrong and how you can correct it. You’ve a legal obligation in business to keep accounting records from the outset and not just wait until your business runs into serious problems. If, as a director or owner of a business, you can’t see when you’re heading for a financial reef, you may find yourself in deep trouble, if not actually heading for jail – and definitely not collecting £200 on the way.

Keeping the Books

To survive and prosper in business you need to know how much cash you have, and what your profit or loss on sales is. You need these facts on at least a monthly, weekly or occasionally even a daily basis to survive, let alone grow.

Recording financial information

Although bad luck plays a part in some business failures, a lack of reliable financial information plays a part in most. However, businesses have all the information they need to manage well close at hand. Among the bills you have to pay, invoices to raise, petty cash slips to file and bank statements to diagnose, you’ve enough to give you a true picture of your business’s performance.

In any event, if you plan to trade as a limited company (see Chapter 5), the Companies Act 1985 requires you to ‘keep adequate records sufficient to show and explain the company’s transactions’.

- To know the cash position of your business precisely and accurately

- To discover how profitable your business really is

- To see which of your activities are profitable and which aren’t

- To give bankers and other sources of finance confidence that your business is being well managed and that their money is in good hands

- To allow you to calculate your tax bill accurately

- To help you prepare timely financial forecasts and projections

- To make sure that you both collect and pay money due correctly

- To keep accountancy and audit costs to a minimum

Starting simple with single entry

If you’re doing books by hand and don’t have a lot of transactions, the single-entry method is the easiest acceptable way to go.

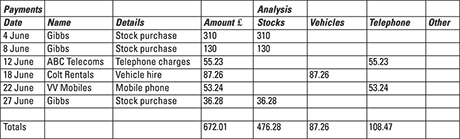

You may benefit from separating different types of income and expense into categories – for example, stock, vehicles, telephone – as in Figure 13-1. This separation lets you see how much you’re spending or receiving in each area.

Figure 13-1: An example of an analysed cash book.

You need to keep copies of paid and unpaid sales invoices and the same for purchases, as well as your bank statements. You then reconcile (match) bank statements to your cash book to tie everything together.

Dealing with double entry

If you operate a partnership or trade as a company, you may need a double-entry bookkeeping system from the start.

A double-entry bookkeeping system requires two entries for each transaction – hence the name – and every transaction has two effects on the accounts. For example, when you buy an item of stock for sale and pay for it in cash, your cash balance goes down and your amount of stock goes up by the same amount, keeping everything in balance.

Choosing the right accounting program

With the cost of a basic computerised accounting system starting at barely £100, and a reasonable package costing between £200 and £500, planning to use such a system from the outset is sensible. If you’re at all concerned as to whether such software represents value, try out Intuits SimpleStart on a free trial basis (http://quickbooks.intuit.co.uk). Thereafter it costs around £8 a month. Or, if you can face having adverts pop up from time to time, Wave, which makes cloud-based, integrated software and tools for small businesses, offers a free-forever accounting package at www.waveapps.com/accounting.

Using a computerised accounting system means no more arithmetical errors. As long as you enter the information correctly, the computer adds it up correctly. With a computer, the £53.24 mobile phone expenditure in Figure 13-1 is input as an expense (a debit), and then the computer automatically posts it to the mobile phone account as a credit. In effect, the computer eliminates the extra step or the need to master the difference between debit and credit.

Routine tasks, such as filling in tax and value added tax (VAT) returns, take minutes rather than days with a computer. The system can ensure that your returns are accurate and fully reconciled. With a computerised system, invoices are always accurate. You can see at a glance which customers regularly take too long to pay. You’ve two main options in your choice of your first accounting system:

- Manual: If you think that a manual system is best for your purposes, you can get sheets of analysis paper with printed columns for accounting entries, and put in your own headings as appropriate. Or you can buy off-the-shelf sets of books from any office stationer’s outlet. These cost anything from £10 to £20 for a full set of ledgers. Hingston Publishing (http://hingston-publishing.co.uk/accounts-books) produces small business accounts systems for both VAT and non-VAT registered businesses for about £15.

- Accounting software: If you decide to take the plunge and go straight for accounting software, you’ve a myriad of software providers to choose from that serve the small business market with software for bookkeeping. These are a selection of the more popular packages and providers:

- Mamut (Formerly Mind Your Own Business; www.mamut.com/uk) offers a range of accounting package systems, starting with its Mamut One Office Accounting costing £118.80 including VAT.

- QuickBooks (http://www.intuit.co.uk/quickbooks/accounting-software.jsp) offers a range of products from around £8 a month up to £30 a month for a system that can automate the VAT return as well as help with budgeting, purchase orders and stock holding. The software is cloud-based.

- Sage One (http://shop.sage.co.uk/accountssoftware.aspx) is Sage’s entry-level product. It costs £5 a month plus VAT, with more sophisticated desktop-based products available for a one-off purchase price of up to £619 plus VAT.

- TAS FirstBooks (http://shop.tassoftware.co.uk/firstbooks.aspx) is aimed specifically at the needs of new, smaller companies. Online support within the product is generally comprehensive, and a manual helps to explain more advanced features. This fairly basic system costs £99 plus VAT to purchase one licence.

Outsourcing bookkeeping

Accountants and freelance bookkeepers can do all your bookkeeping work – at a price. The rate is anything from £20 per hour upwards.

Bookkeeping services range from a basic write-up of the entries and leave-the-rest-to-you approach, through to providing weekly or monthly accounts, perhaps with pointers as to what may be going wrong. Services even exist that act as a virtual finance director, giving you access to a senior accountant who may sit on your board.

The bookkeeper’s most routine but vital task may be doing the payroll. If you don’t get this done on time and correctly, both staff and HMRC, for which you have to collect pay as you earn (PAYE), become restless. A weekly payroll service for up to ten employees costs upwards of £85 per month. If you pay everyone monthly, the cost drops to about a third of that figure.

If you go down this route, you probably need someone local, so ask around to find someone who uses a bookkeeper and is satisfied. Alternatively, turn to the phone book, or use Service Start (http://uk.servicestart.com), which gets up to five price quotes from rated bookkeeping service providers all over the UK.

As with an accountant, make sure that a prospective bookkeeper is adequately qualified. The International Association of Book-keepers (IAB; website www.iab.org.uk) and the Institute of Certified Bookkeepers (www.bookkeepers.org.uk) are the two professional associations concerned.

Understanding Your Accounts

Keeping the books is one thing, but being able to make good use of the information those accounts contain is quite another. You need to turn the raw accounting data from columns of figures into statements of account. Those accounts in turn tell you how much cash your business has, its profit or loss numbers and how much money you’ve tied up in the business to produce those results. The following sections discuss some of the key accounting statements and performance analyses.

Forecasting cash flow

In the language of accounting, income is recognised when a product or service has been sold, delivered or executed, and the invoice raised. Although that rule holds good for calculating profit (see ‘Reporting Your Profits’, later in this chapter), it doesn’t apply when forecasting cash flow.

Chapter 8 covers how to prepare a cash-flow forecast. Profit is what may be generated if all goes well and customers pay up, and you can think of cash flow as the cold shower of reality, bringing you sharply back to your senses.

Reporting your profits

A key use of bookkeeping information is to prepare a profit and loss account.

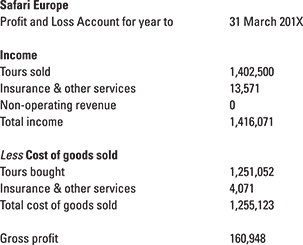

At its simplest, the profit and loss account has at its head the period covered, followed by the income, from which you deduct all the expenses of the business to arrive at the profit (or loss) made in the period. Figure 13-2 shows a sample account.

Figure 13-2: A basic profit and loss account.

Although the information shown in the profit and loss account is certainly better than nothing, you can use basic bookkeeping information to give you a much richer picture of events within the business. Provided, that is, that you’ve set up the right analysis headings in the first place.

The following sections show, step by step, how to build up a profit and loss account to give you a more complete picture of the trading events of the past year at Safari Europe, the example I use in the following sections.

Calculating gross profit

One of the most important figures in the profit and loss account is the gross profit. Whatever your activity, you have to buy certain ‘raw materials’. Those include anything you have to buy to produce the goods and services you’re selling. So if you sell cars, the cost of buying in the cars is a raw materials cost. In Safari’s case, because the company is in the travel business, the costs of airline tickets and hotel rooms are the raw material of a package holiday.

The amount left from the sales revenues after deducting the cost of sales, as these costs of ‘making’ are known, is the gross profit. This is really the only discretionary money coming into the business, where you have some say over how it’s spent. Figure 13-3 shows a sample profit calculation.

Figure 13-3: An example gross profit calculation.

In the account shown in Figure 13-3, you can see that Safari has two sources of income, one from tours and one from insurance and other related services. It also, of course, has the costs associated with buying in holidays and insurance policies from suppliers.

The difference between the income of £1,416,071 and the cost of the ‘goods’ the company has sold is just £160,948. That’s the sum that the management has to run the business, not the much larger, headline-making figure of nearly £1.5 million.

Figure 13-4 shows how to calculate gross profit in a business that makes things rather than selling services.

Figure 13-4: A manufacturer’s gross profit.

In the example in Figure 13-4, the basic sum is the same as for a service business, as shown in Figure 13-3. Take the cost of goods from the sales income and what’s left is gross profit. The cost of goods is calculated by noting the stock at the start of the period, adding in any purchases made and deducting the closing stock.

You also need to build in the labour cost in production and any overheads, such as workshop usage, and deduct those in order to arrive at the gross profit, as shown in Figure 13-5.

Figure 13-5: Expanded gross profit calculation.

Reckoning expenses

After you calculate the gross profit, you have to allow for all the expenses that are likely to arise in running the business. Using the Safari case as a working example, Figure 13-6 shows all the costs usually associated with running the business, such as rent, rates, telephone, marketing and promotion, and so forth. Although all these expenses are correctly included, they aren’t all allowable for tax purposes in every country. I look at taxation in Chapter 14.

Figure 13-6: Business expenses.

The ‘Total expenditure’ heading isn’t quite accurate. Other expenses associated with running a business aren’t included here, but these expenses are treated in a slightly different way, for reasons that should become apparent as you read on about the different types of profit.

Appreciating the different types of profit

You can measure profit in several ways:

- Gross profit is the profit left after you’ve deducted all costs related to making what you sell from income (see the beginning of this section, ‘Reporting Your Profits’, for what represents income).

- Operating profit is what’s left after you take the expenses (or expenditure) away from the gross profit.

- Profit before tax is what you get after deducting any financing costs. This is a measure of the performance of the management, which is important if the owners and managers aren’t the same people, as may be the case when you start to employ staff. The reasoning here is that the operating management can have little influence over the way in which the business is financed (no borrowings means no interest expenses, for example), or the level of interest charges.

In Figure 13-7, taking away the financing costs, in the example £5,000 interest charges, leaves a profit before tax of £26,373. Finally, you deduct tax to leave the net profit after tax, the bottom line. This sum belongs to the owners of the business and, if the company is limited, is what dividends can be paid from.

Figure 13-7: Levels of profit.

Accounting for Pricing

Setting a selling price for your wares is one of the most important and most frequent business decisions that anyone running a business has to make. At first glance, it doesn’t seem such a big deal. Just add up all the costs, add a healthy profit margin and as long as the customers don’t rush for the exit you’re in business. Unfortunately, the first part of that sentence contains a few traps for the unwary.

Complications start when you have to get to grips with the characteristics of costs. Not all costs behave in exactly the same way. For example, the rent on a shop, office or workshop is a fixed sum, payable monthly or quarterly. Your landlord doesn’t usually expect you to pay more rent if you get more customers, nor is he especially generous if you’ve a particularly lean period. (One exception to this rule comes if you’re able to negotiate a rent geared to performance, an offer landlords have been known to make to some retailers.) The business rates on any premises and the cost of an advertisement in the local paper are also fixed costs. That term shows that the cost in question doesn’t vary directly with the volume of sales, not that the cost itself has been immutably settled and you’re committed to pay it. You don’t have to advertise and you do have to pay business rates, but both are fixed costs.

Contrast that with the cost of the products you plan to sell. Assume for a moment that you’re selling just one product, a bottle of wine costing £3 to buy in. The more you sell, the more your stock costs to buy. That type of cost varies directly with the volume of sales you achieve, and in a rare display of user-friendliness from the accounting profession is known as variable. The cost of each individual bottle may or may not vary – your supplier may or may not change the price, perhaps lowering it to win more business from you or upping it to meet the chancellor of the exchequer’s ever-growing demand for more tax. But the nature of the cost means that the total cost does vary as your sales volume changes.

The main tool that can help you with pricing decisions is breakeven analysis. Using that tool, which I explain in the following sections, helps you to set the best price for single or multiple products, to see how much you have to sell to hit your profit goals and to deal with changing your prices.

Breaking even

To keep things simple: your business plans to sell only one product, for example the wine I mention in the previous text, and you only have one fixed cost, the rent. Figure 13-8 sets out a graphical picture of how your costs stack up. The vertical axis shows the value of sales and costs in thousands and the horizontal axis shows the number of units sold, in this case bottles of wine. The rent is £10,000 for the year, represented by a straight line labelled ‘fixed costs’. The angled line running from the top of the fixed costs line shows the amount of the variable costs. Sell zero bottles and you incur zero additional costs. In this case, the total costs are £10,000 plus £0 equalling £10,000. Every bottle you buy in adds £3 of variable costs (you have to buy the wine in!!) to the total costs.

Figure 13-8: Breakeven chart.

You need to calculate the breakeven point – that is, when you’ve made enough money from selling wine to pay the rent. The sales revenue line moves up at an angle from the bottom left-hand corner of the graph. If you plan to sell your wine at £5 a bottle, you calculate the figures for this line by multiplying the number of units sold by that price.

The breakeven point is the stage at which a business starts to make a profit – when the money coming in from sales is higher than the fixed and variable costs added together. For your wine business, you can see from the chart that this point arises when you’ve sold 5,000 bottles. You don’t have to draw a chart every time you want to work out your breakeven point – you can use a simple formula.

Breakeven point = Fixed costs

Selling price – Unit variable cost

= 10,000 = 5,000 units

5 – 3

Pricing for profit

You have to break even if you want to remain in business, but doing so isn’t enough on its own. You need to make a profit over and above your breakeven point.

Profit isn’t an accident of arithmetic discovered by your accountant at the year end. Profit should be a specific, quantified goal that you set in advance. Look again at the earlier wine selling example: you plan to invest £10,000 in a year’s rent, and you need to hold at least £5,000 worth of stock too, making £15,000 total costs. So what return can you expect on the money you’re investing? If you invested the same amount in other people’s businesses by buying an average bundle of shares on the stock market, you may expect to get a return of £1,200, around 8 per cent. If you went for more risky start-up and early-stage ventures, a venture capital firm may recommend that you look for a return of between 20 and 30 per cent.

To keep the numbers simple again, say your profit goal is to make £4,000 profit, a return of 27 per cent (4,000 ÷ 15,000 x 100). How many bottles of wine do you need to sell to break even and meet your profit goal? The new equation must include your desired profit, so it looks like this:

Break-even profit point (BEPP) = Fixed costs + Profit goal

Selling price – Unit variable cost

= 10,000 + 4,000 = 14,000 = 7,000

5 – 3 2

From the formula, you now know that to reach your profit goal you have to sell 7,000 bottles of wine. Better still, this powerful little equation allows you to change each element and experiment to arrive at the optimum result. For example, say that after doing market research you conclude that you’re unlikely to sell 7,000 bottles of this wine, but that you can sell 6,000. What does your selling price have to be to make the same profit?

Using the BEPP equation and inserting ‘x’ for the element you’re changing, you can calculate the answer:

Break-even profit point (BEPP) = Fixed costs + Profit goal

Selling price – Unit variable cost

= 6,000 = 10,000 + 4,000

x – 3

Therefore x – 3 = 10,000 + 4,000 = 2.33

6,000

x = 3 + 2.33 = 5.33

So your new selling price has to be £5.33 a bottle if you need to make £4,000 profit from the sale of 6,000 bottles. If the market can bear that price, great; if not, then you need to look for ways to decrease the fixed and variable costs, or to sell more, if you’re to meet your profit goal.

Building in more products

The example so far has been for a one-product company, but what if you plan to sell more than just one type of wine – or perhaps even add crisps and chocolates too? When you reach this stage, you need to work from your gross profit percentage (for how to calculate this percentage see ‘Analysing Performance’, later in this chapter).

If, for example, you’re aiming for a 40 per cent gross profit, your fixed costs are £10,000 and your profit goal is £4,000, then the sum is as follows:

BEPP = 10,000 + 4,000 = 14,000 = £35,000

0.4 0.4

If you got a bit lost about where the 0.4 came from, don’t worry; that’s just 40 per cent expressed as a decimal, a step you need to take before you can use the number. What you now know is that at a 40 per cent gross profit margin you need to sell £35,000 worth of wine, chocolates and crisps to hit your profit goal. Your accountant can help with these calculations, and the Harvard Business School website has a useful tutorial that links with its breakeven spreadsheet (see the preceding section).

Handling price changes

The most sensitive and revisited area of business strategy is pricing. You can check out the impact of a particular pricing policy on your profitability using breakeven analysis (see ‘Pricing for profit’, earlier in this chapter, for more details). As part of your strategy, you may consider changing your price. All things being equal, a lower price should open up a bigger market and so increase sales. But should you reduce your price?

As a rule of thumb, if you decrease your prices by 5 per cent you have to increase your sales by three times that percentage, just to make the same level of profit. This increase depends on the gross profit you’re achieving, but the figure given holds good for gross profits of 30 to 40 per cent.

Conversely, if you push your prices up by 5 per cent, you can lose around a seventh of your business before you’re any worse off in terms of profit.

Balancing the Books

You have to know where you are now before making any plans to go anywhere else. Without a starting point, any journey is bound to be a confusing experience. A business sums up its current position in a balance sheet, the business’s primary reporting document. The balance sheet contains the cumulative evidence of financial events, showing where money has come from and what’s been done with that money. Logically, the two sums must balance.

In practical terms, balancing your sums takes quite a bit of work, the hardest bit of which isn’t necessarily the balancing part, but figuring out the numbers. Your cash-in-hand figure is probably dead right, but can you say the same of the value of your assets? Accountants have their own rules on how to arrive at these figures, but they don’t pretend to be anything more than an approximation. Every measuring device has inherent inaccuracies, and financial controls are no exception.

To help balance the books, the balance sheet sets out a business’s assets and liabilities in way that makes it easier to understand crucial relationships. In the following sections, I look at the balance sheet and the essential technical terms that you need to grasp in order to get the full picture of how a business is faring.

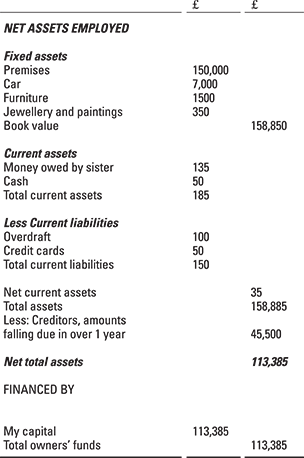

A balance sheet

In formal accounts the figures are set out vertically rather than in horizontal fashion, as reflected in Figure 13-9. The business’s long-term borrowings, in this case the mortgage and hire purchase charges, are named Creditors, amounts falling due in over 1 year and deducted from the total assets to show the Net total assets being employed.

Figure 13-9: Jane Smith Limited Balance Sheet at 5 April 201X.

The bottom of the balance sheet in Figure 13-9 shows how the owners of the business have supported these assets, in this case by their own funds. As you can see later, they could also have invested profit made in earlier years back into the business (see the later section ‘Understanding reserves’). I’ve also assumed that the owner’s house is now a business premises owned by her company. (This assumption has wider implications, but none relevant to the arithmetic or the balance sheet.)

Categorising assets

Accountants describe assets as valuable resources, owned by a business, that were acquired at a measurable monetary cost.

One useful convention recommends listing assets in the balance sheet in their order of permanence; that is, starting out with the most difficult to turn into cash and working down to cash itself. This structure is practical when you’re looking at someone else’s balance sheet, or comparing balance sheets. It can also help you recognise obvious information gaps quickly.

Accounting for liabilities

Liabilities are claims against the business. These claims may include such items as tax, accruals (which are expenses for items used but not yet billed for, such as telephone and other utilities), deferred income, overdrafts, loans, hire purchase and money owed to suppliers. Liabilities can also be less easy to identify and even harder to put a figure on, bad debts being a prime example.

Understanding reserves

Reserves are the accumulated profits that a business makes over its working life, which the owner has ploughed back into the business rather than taking them out.

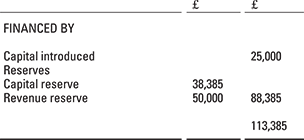

Jane Smith’s balance sheet (see the earlier section ‘A balance sheet’) shows her capital as being the sole support for the liabilities of the business. The implication is that she put this whole sum in at once. In practice, this sum is much more likely to have been paid over time, and in a variety of ways.

Perhaps she started out in business – because that’s how you must now look at her affairs – with a sum of £25,000. In the period since she’s been in business, she’s made a net profit after tax of £50,000 and put this amount back into her business to finance growth. In addition, the premises that she bought a few years ago for £111,615 have just been re-valued at £150,000, a paper gain of £38,385.

The bottom portion of her company balance sheet may now look as shown in Figure 13-10.

Figure 13-10: Jane’s reserves.

The profit of £50,000 ploughed back into the business is called a revenue reserve, which means that the money actually exists and can be used to buy stock or more assets. The increase in value of the business premises is, on the other hand, a paper increase. Jane can’t use the £38,385 increase in capital reserves to buy anything, because it’s not in money form until the premises are sold. However, she can use that paper reserve to underpin a loan from the bank, so turning a paper profit into a cash resource. Both reserves and the capital introduced represent all the money that the shareholder has invested in this venture.

Analysing Performance

Gathering and recording financial information is a lead-up to analysing a business to see how well (or badly) it’s doing. This analytical process requires tools, in this case ratios, and you need to understand their usefulness and limitations before you can use them to good effect.

Using ratios

All analysis of financial information involves comparisons. Because a business is constantly changing, the most useful way to measure activity is through ratios. A ratio is simply one number expressed as a proportion of another. Travelling 100 miles may not sound too impressive, until you realise it took one hour. The ratio here is 100 miles per hour. If you know that the vehicle in question has a top speed of 120 miles per hour, you’ve some means of comparing it to other vehicles, at least in respect of their speed. In finance, too, ratios can turn sterile data into valuable information in a wide range of different ways and help you make choices.

I describe the key financial ratios you need from the outset in the following sections. Monitor all these at least on a monthly basis.

Gross profit percentage

To calculate gross profit percentage (percentage is one form of ratio where everything is described in terms of a relationship to 100), you deduct the cost of sales from the sales and express the result as a percentage of sales. The higher the percentage, the greater the value you’re adding to the goods and services you’re producing. Figure 13-11 shows the calculation.

Figure 13-11: Formula for calculating gross profit percentage.

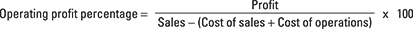

Operating profit percentage

Calculating the operating profit percentage gives you a measure of how well the management is running the business, because operating expenses for which the management is responsible form a component of the calculation. Financing decisions are presumed to be the owner’s responsibility; interest and taxation are set by the government, so those numbers are out of management control and accountability.

To calculate this number, you deduct from profit not only the cost of sales but also expenses, as Figure 13-12 shows.

Figure 13-12: Calculating operating profit.

Net profit percentage

Working out your net profit essentially gives you your business’s bottom line, telling you how much money is left for you to take out or reinvest in your business. A higher percentage means that you’re making more money from each pound of sales generated.

You can calculate net profit after you pay tax or before – earnings before interest and tax, known as EBIT.

In its after-tax form, which Figure 13-13 shows, net profit percentage represents the sum available for the business to distribute as dividends or retain to invest in its future.

Figure 13-13: Calculating net profit percentage.

Return on capital employed

This number, frequently abbreviated to ROCE, is the primary measure of performance for most businesses. If, for example, you invested £10,000 in a bank and at the end of the year it gave you £500 interest then the return on your capital is 5 per cent (£500 ÷ 10,000 x 100 = 5 per cent).

A business calculates this ratio by expressing the operating profit (profit before interest and tax) as a percentage of the total capital employed – both in fixed assets and in working capital, called net current assets in the balance sheet. Figure 13-14 shows the formula for calculating ROCE. Refer to Figure 13-12 to work out the operating profit number.

Figure 13-14: Calculating return on capital employed.

If you think about it, return on capital employed is the same as the return on the shareholders’ funds plus the long-term loans, or the ‘financed by’ bit of the balance sheet.

Current ratio

You calculate the current ratio by dividing your current assets by your current liabilities. Only one rule exists about how high (or low) the current ratio should be. It should be as close to 1:1 as the safe conduct of the business allows. This rule isn’t the same for every type of business, though. For example, a shop buying in finished goods on credit and selling them for cash can run safely at 1.3:1. A manufacturer, with raw material to store and customers to finance, may need over 2:1. This difference is because the period between paying cash out for raw materials and receiving cash in from customers is longer in a manufacturing business than in a retail business.

Average days’ collection period

Any small business selling on credit knows just how quickly cash flow can become a problem. You calculate the average collection period ratio by dividing the value of your debtors by the value of credit sales, and then multiplying that by the days in the period in question. The result is expressed in days, so you can see in effect how many days it takes for your customers to pay up, on average.

A period of 60 days is fairly normal for customers to take before paying up. Around 45 days is a good target to aim for and 90 days is too long to let payment go without chasing. The above is a good control ratio, which has the great merit of being quickly translatable into a figure any businessperson can understand, showing how much giving credit costs you.

If you’re selling into overseas markets, the practice on punctual payments can vary widely. Knowing your average collection period for these markets can help you to plan cash flow more effectively.

Stock control ratio

A simple way to tackle stock control is to see how many times your business turns its stock over each year. Dividing the cost of sales by the value of your stock gives you this ratio. The more times you can turn your stock over, the better.

Gearing down

The more borrowed money a business uses, as opposed to the money the shareholders have put in (through initial capital or by leaving profits in the business), the more highly geared the business is. Highly geared businesses can be vulnerable when sales dip sharply, as in a recession, or when interest rates rocket, as in a boom. Figure 13-15 shows how to calculate gearing percentage.

Figure 13-15: Calculating gearing percentage.

Gearing levels in small firms average from 60 per cent down to 30 per cent. Many small firms are probably seriously over-geared, especially when they’re in the first stages of growth.

- Bankrate.com, an aggregator of financial rate information, has seven free small business ratio calculators that cover all aspects of measuring financial performance (http://www.bankrate.com/brm/news/biz/bizcalcs/ratiocalcs.asp).

- SME Toolkit, by the International Finance Corporation (IFC), a member of the World Bank Group, includes free ratio calculator tools (go to www.smetoolkit.org, Accounting and Finance, and then Financial Management and Reporting).

Keeping on the Right Side of the Law

Whether the money in the business is yours alone, provided by family and friends or supplied by outside financial institutions, you’ve a legal responsibility to make sure that you keep your accounts in good order at all times. If you’re successful and need more money to expand, you need financial information to prove your case. If things aren’t going so well and you need to strengthen your position to weather a financial storm, you’ve even greater need of good accounting information.

Whatever the circumstances in the background, tax and VAT authorities need to be certain that your figures are correct and timely.

Carrying out an audit

Companies with balance sheet totals in excess of £3.26 million or annual turnovers above £6.5 million are required to appoint an auditor and have their accounts audited. However, a large number of much smaller businesses still have to have their accounts audited. If, for example, you’ve shareholders owning more than 10 per cent of your firm, they can ask for the accounts to be audited.

The auditor’s job is to report to the members (shareholders) of the company as to whether the accounts have been properly prepared, taking notice of the appropriate accounting rules. The auditor must also report as to whether the accounts give a true and fair view of the state of the company’s affairs. In order to arrive at a conclusion, the auditor examines the company’s records on a test basis to ensure that the accounts aren’t materially incorrect. This examination doesn’t mean that the auditor checks every detail, but he does look at a representative sample of transactions to get a feel for whether or not the books are being properly kept.

Filing your accounts

If you’re trading as a company then you have to file your accounts with Companies House (www.companieshouse.gov.uk) each year.

All companies must prepare full accounts for presentation to their shareholders, but small and medium-sized companies can send abbreviated accounts to the registrar of companies. Abbreviated accounts contain little information that can be of use to a competitor. Nothing is given away on turnover or margins, for example, a luxury denied to larger companies. Small companies’ accounts (ones with less than £6.5 million turnover, balance sheet total less than £3.26 million and fewer than 50 employees on average, to be precise) delivered to the registrar must contain

- An abbreviated balance sheet

- Selected notes to the accounts, including accounting policies, share capital, particulars of creditors payable in more than five years and the basis of any foreign currency transactions

- A special auditor’s report (unless exempt from audit; see the preceding section on audits)

Managing Your Accountant

Accountancy is just another business discipline, like selling, research, administration or production. So you need to manage, motivate, reward and appraise your accountant, like any other member of staff. Whoever acts as your company accountant, be he a part-timer from outside or a fellow director, you as the owner must take the lead.

- Your monthly management accounts should be available within a week of the end of each month. You have the wrong accountant or the wrong accounting system if you can’t achieve this standard. If you don’t yet have monthly management accounts, make that your accountant’s next measurable goal.

- Accounting systems and reports should be simple, free of jargon and supported by clear written explanations of the key issues to consider. For example, if profits are down by 10 per cent, as well as the bald figures an explanation that this reduction was caused by a 5 per cent reduction in sales of product X and a 5 per cent increase in raw material costs gives a clear indication of responsibilities and possible remedies.

- Your accountant should also ensure that your books and records are kept to the standard required by company law. He must also see that your accounting policies meet the required standards and that accounts, VAT returns, and PAYE and tax demands are dealt with in a timely manner.

This chapter gives you a good grounding in keeping track of finances, but keep in mind that now’s not the time to be shy in coming forward for advice. According to the 2012 Small Business Survey carried out for the UK Government, 46 per cent of new business sought advice from an accountant, mostly on financial matters to do with running the business. One hundred per cent would be a far preferable figure.

This chapter gives you a good grounding in keeping track of finances, but keep in mind that now’s not the time to be shy in coming forward for advice. According to the 2012 Small Business Survey carried out for the UK Government, 46 per cent of new business sought advice from an accountant, mostly on financial matters to do with running the business. One hundred per cent would be a far preferable figure. All you need to do is record and organise that information so that the financial picture becomes clear. The way you record financial information is called bookkeeping.

All you need to do is record and organise that information so that the financial picture becomes clear. The way you record financial information is called bookkeeping. If you plan to submit your accounts online, you need an accounting system that meets the requirements of Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs (HMRC). A range of Internet-filing-enabled software and forms is available from HMRC and commercial software and service suppliers. You can use these to file company tax returns, including accounts and computations, online. HMRC provides a list of software suppliers at

If you plan to submit your accounts online, you need an accounting system that meets the requirements of Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs (HMRC). A range of Internet-filing-enabled software and forms is available from HMRC and commercial software and service suppliers. You can use these to file company tax returns, including accounts and computations, online. HMRC provides a list of software suppliers at  You can check out the letters that anyone in the accounting profession uses after his name or the bodies he claims to be a member of at the Directory of Essential Accountancy Abbreviations, maintained by the Library and Information Service at the Institute of Chartered Accountants in England and Wales (

You can check out the letters that anyone in the accounting profession uses after his name or the bodies he claims to be a member of at the Directory of Essential Accountancy Abbreviations, maintained by the Library and Information Service at the Institute of Chartered Accountants in England and Wales (