3 Corporate Culture and Internationalization

3.0 Statement of the problem

Nepotism in Vietnam

A German company had established very clear global purchasing guidelines: no more than 30 percent of any particular item could be supplied by one vendor, and quotes had to be obtained from at least three different suppliers; and contracts were to be awarded purely on the basis of price, delivery terms, reliability and quality.

Meier, the German regional manager for South-East Asia, was disturbed to note that, despite several reminders, the subsidiary in Vietnam did not appear to be following the guidelines. In fact, the range of suppliers they used seemed to be very limited, and most of them were Vietnamese.

The subsidiary’s Vietnamese manager seemed very unconcerned when Meier raised this problem with him. “Well, of course most of our suppliers are Vietnamese”, he said. “I only use vendors I am related to.” Meier was shocked and remained silent for a moment. Then he calmly explained that this practice was against company guidelines. “But why?” asked the Vietnamese manager. “Because it is unethical and anti-competitive. We are not allowed to do it in Germany, and we cannot allow our subsidiaries to behave in this way.” It was the Vietnamese manager’s turn to be shocked: “But I cannot see what the problem is”, he said. “My family is much more loyal and reliable than people I do not know. I can call them any time of day or night. They cannot escape me. And, of course, they give me much better discounts. Surely, you do not want me to use suppliers I do not trust.” Meier raised and lowered his eyebrows, and remained silent.

Rothlauf, J., in: Seminarunterlagen, 2005, p. 14

As the world is becoming increasingly interconnected, one could argue that intercultural competence is also gaining critical importance in numerous ways – whether it is in global workforce development, in resolving conflicts, in facilitating intercultural coexistence on a local level or in working together to address the world’s most pressing issues – including the ethical, social, ecological and cultural challenges of globalization. Yet, the term “intercultural competence” has been notoriously difficult to define and assess.

There are a lot of different definitions as far as the term intercultural competence is concerned. Deardorff (2006, p. 5) says that intercultural competence “is the ability to interact effectively and appropriately in intercultural situations, based on specific attitudes, intercultural knowledge, skills and reflection.”

Bennett (2011, p. 4) describes it as “a set of cognitive, affective, and behavioural skills and characteristics that supports effective and appropriate interaction in a variety of cultural contexts”

3.1 Corporate cultures in global interaction

Long neglected, the corporate culture has by now become one of the major competitive factors in the globalization process. Opening up new markets, either through mergers, acquisitions or start-ups, presents the management not only with economic challenges. Business success and economic continuity depend on the connection, design as well as the transparency and acceptance of the corporate culture’s core values across the international corporate locations. Though intercultural problems are often recognized in the course of the daily working and communication processes, they are not yet sufficiently taken into account for important decisions, because reputedly “hard” economic arguments prevail. However, studies have shown that around 70 % of the business combinations do not achieve their goals. (Mohn, 2005, p. 4)

Toyota’s corporate culture – guiding principles

(Sonja A. Sackmann)

- Honour the language and spirit of the law of every nation and undertake open and fair corporate activities to be a good corporate citizen of the world.

- Respect the culture and customs of every nation and contribute to economic and social development through corporate activities in the communities.

- Dedicate ourselves to providing clean and safe products and to enhancing the quality of life everywhere through all our activities.

- Create and develop advanced technologies and provide outstanding products and services that fulfill the needs of the customers worldwide.

- Foster a corporate culture that enhances individual creativity and teamwork value, while honouring mutual trust and respect between labour and management.

- Pursue growth in harmony with the global community through innovative management.

- Work with business partners in research und creation to achieve stable and long-term growth and mutual benefits, while keeping ourselves open to new partnerships.

In: Bertelsmann Stiftung (Hrsg.), Toyota Motor Corporation: Eine Fallstudie aus unternehmenskultureller Perspektive, 2007, p. 16.

3.1.1 A research project on global cultural development

Between October 2003 and September 2004, 200 international managers from the focus regions Germany/Switzerland (88 interviews), Japan (39) and the USA (73) were asked in semi-structured in-depth interviews about their assessment of the possibilities and limits of a transnational corporate culture. The study explicitly concentrated on the pool of international executives (first to third management level). The participating companies were selected on the basis of accessibility and their willingness to cooperate.

Companies such as BASF, Henkel, Deutsche Post World Net, Volkswagen, Bertelsmann, Lufthansa, Pfizer, Toyota and Nestlé agreed to participate. In cooperation with the executives, a framework of action for an improved and more effective process of cultural development in multinational companies was developed. The aim was to promote intercultural collaboration within the company and to enhance the economic and social productivity and efficiency in the global corporate sector. (Spilker/Lippisch, 2005, p. 7).

3.1.2 Cultural integration drivers

Seven instruments for achieving cultural integration, which are described as cultural integration drivers by Blazejewski & Dorow (2005), have been identified as action-guiding in the course of the study. In the form of checklists, the respective activities, which allow putting the project’s findings into practice all around the world, will be presented in the following (Blazejewski/Dorow, 2005, pp. 38ff):

Fig. 3.1: Seven instruments for achieving cultural integration

Source: Blazejewski/Dorow, 2005, p. 11

“Check list: Cultural Vision

- Written definition of core corporate values: This makes it easier to communicate values to new employees, after mergers or acquisitions, for example, and provides a binding, common framework for everyone.

- Clear, creative communication of core values: Values are often overlooked if they are sent out by e-mail or posted on the intranet. They should be brought to the attention of employees in their immediate work environments. It is important to encourage thinking about cultural issues as part of the everyday routine, for example by scheduling this regularly.

- Five to seven core values are sufficient: People cannot really absorb or comprehend more than that, let alone apply them in day-to-day decision making.

- Translation into local languages: When a list of values has been drawn up only in English, the result is frequent misunderstandings and uncertainty about how to interpret and apply them in practice. In addition, discussion about how these values should be translated and interpreted offers an excellent opportunity for dialogue within the subsidiaries on the company’s culture.

- Operationalize the core values: These often quite abstract values must be put into concrete terms, through examples or descriptions of appropriate behaviour. The concept of “integrity” can only be understood by giving examples, for instance by pointing out that employees are not allowed to exchange gifts with customers or suppliers.

Check list: Local Dialogue

- Systematically take the local perspective into account: It is not enough to only involve the top management echelon, which tends to focus on headquarters. It is important from the very beginning to include employees of the subsidiaries in developing global core values. This is crucial to ensure that the core values are accepted early on and reinforced throughout the company.

- Local application: Subsidiaries should be encouraged to give serious thought to interpreting core values from a local perspective at dedicated forums and workshops. Regional interpretations of company values and local codes of conduct should be put in writing so that erroneous or confusing interpretations can be identified early on and discussed.

- Solve conflicts through cooperation: Facilitate dialogue between the parent company and subsidiaries to resolve differences between the global core values and local interpretations or traditional business practices. If subsidiaries are left to resolve these conflicts on their own, local employees may react with cynicism or even reject the global value initiative altogether.

Check list: Visible Action

- Living one’s values: Among leadership personnel in particular, consistency between words and deeds needs to be apparent and communicated at all times. The concept of a global corporate culture loses all credibility if those at the highest levels fail to take the company’s values seriously.

- Emotional commitment to core values: It is not enough for the global values to be expressed as one more formal regulation within the organization. If values are to be credible, leadership personnel, serving as cultural role models, must demonstrate personal, emotional commitment and be able to enthusiastically communicate global values. Superficial, noncommittal lip service by superiors as an afterthought at management meetings, under the heading of “miscellaneous”, results in cynicism and rejection on the part of employees.

Check list: Communicator

- Institutionalize platforms for dialogue: Make sure there is adequate room for cultural dialogue at both the regional and global level. This includes specific, formal opportunities for communication such as culture-focused workshops and discussion groups, as well as support for an informal cultural exchange. Set aside time for the latter during training sessions or at international project meetings. Personal communication between employees of different cultural backgrounds was consistently identified as the most important means of achieving cultural integration.

- Promote fluency: Even today many employees, including executives, lack the necessary language skills to participate meaningfully in a cultural dialogue. Inadequate language skills prevent them from contributing their own interpretations of core values to the discussion and from establishing intercultural communication networks. In addition to language problems, in some regions there are also cultural barriers to communication that prevent participation in open dialogue. When this is the case, executives must make a special effort to elicit opinions from employees in cultures where people are more reticent, thus enhancing the employees’ ability and willingness to take part in dialogue over the long term.

- Internationalize means of communication in a consistent way: Inhouse intranet pages are still often available only in the language of the headquarters; no more than excerpts are provided in English, if that. This means that foreign employees are often simply unaware of information made available through that medium.

- Globally appropriate artifacts: Symbols, slogans, logos and other artifacts (architecture, room furnishings, work clothing) that are intended to enhance the integration of the company need to be internationally acceptable and associated with positive connotations. Poorly worded English slogans meant to encourage group cohesion end up being ridiculous and imperil the success of the entire initiative.

Check list: Cultural Ambassador

- Ongoing rotation programs: To save money, many companies have recently cut back on their expatriate programs. This can slow down or even prevent cultural integration within the larger company. Even though e-mail and telephone calls are options as well, personal contact with colleagues from other cultural regions is the main method of integration. It is important not only to assign employees from headquarters to other locations, but to increase the number of rotations from or among the regions.

- Allow for flexibility: Because of the different working and living conditions in many countries, rotation programs should be kept flexible in terms of such factors as length of stay, host country, responsibilities and career stage. Rotating younger employees at the beginnings of their careers can give them a global perspective, increase their intercultural competence and lay the groundwork for an international network of contacts. This puts in place important factors needed for intercultural understanding and cultural integration within the company.

- Guarantee a return to the home office: In many regions, foreign assignments fail to materialize for the simple reason that employees would rather forgo the international experience than risk that their return will be poorly organized. Guaranteeing that an attractive option for returning will be available would open up new possibilities for gaining foreign experience, also for American executives, who are often reluctant to be sent abroad.

- Ensure on-site involvement: In spite of the lip service paid to the idea of globalization, employees still frequently feel abandoned before, during and after a foreign assignment. Systematic intercultural mentoring programs in the respective home and host countries can help to facilitate cultural integration and enhance the benefit of cultural experiences for the entire company.

- Internationalize leadership positions: Every career path in the company, including the highly symbolic management board, must also be open to foreign employees in the subsidiaries.

- Put global hiring procedures into effect: Many of the companies already have global procedures for choosing international executives, but foreign employees still have the impression that only those from the home country are actually hired into leadership positions. A lack of transparency quickly leads to the suspicion that headquarters is only paying lip service to the core values of internationality, interculturality and diversity.

- Remedy image problems abroad: A lack of international top executives is often defended by contending that the executives in the subsidiaries are “second-rate”. It is still uncommon to see systematic efforts to deal with the problems of recruiting first-class employees in foreign countries, particularly those who share the company’s basic values (through local sponsoring efforts, links with outstanding local universities).

Check list: Compliance

- Binding core values: When seeking to achieve global integration by developing core values jointly, it is helpful for a company to ensure that employees and executives worldwide share a binding commitment to those values, in order to reflect the importance of the corporate culture in central corporate policy.

- Review compatibility with corporate core values: In many companies the hiring, evaluation and incentive systems are not consistently geared to global corporate values. This can lead to contradictions and a loss of credibility of cultural integration initiatives.

- Control and sanctions: Cultural development needs to be monitored and ensured on a continual basis, through ongoing review processes (employee surveys, regular cultural diagnosis, opportunities to provide feedback, for example through anonymous hotlines). When individuals grossly violate company values, there must be a consistent response and visible consequences; only then will it be possible to ensure the credibility of the cultural initiative.”

3.2 Mergers & acquisitions

The number of mergers and acquisitions (M&A) is on the rise, not only in Europe but all around the world. Reasons for this development include the efforts of companies to cut costs, save time for more improvements and innovations, and improve the quality of the products respectively the services, or simply to become bigger in many ways. The following table provides a short insight into those business transactions. The eastward expansion of the European Union as well as the new emerging markets in Asia have removed barriers and opened up new markets resulting in a quest for “fertile hunting grounds for takeover targets”.

“Coming together is a beginning.

Keeping together is progress.

Working together is success.”

(Henry Ford)

Mergers & Acquisitions – selected major deals in 2013

- 2nd September: Vodafone Group sold Verizon Wireless Inc to Verizon Communications Inc for US$bn 124.1.

- 14th February: H.J. Heinz Company was acquired by Berkshire Hathaway Inc and 3G Capital for US$bn 27.4.

- 6th February: Liberty Global Plc acquired Virgin Media Inc for US$bn 25.0.

- 24th June: Kabel Deutschland Holding AG was bought by Vodafone Group Plc for US$bn 11.3

- 24th September: Applied Materials acquired Tokyo Electron Limited for US$bn 8.7.

3.2.1 The terms “merger” & “acquisition”

To distinguish an acquisition from a merger, it is essential to understand that the term “merger” is usually referred to as a fusion of two approximately equal-sized companies, while the term “acquisition” describes the process of one larger corporation purchasing a smaller company which will then vanish (Pride/Hughes/Kappor, 2002, p. 146).

The basis for a merger are two or more economically and legally independent entities. A merger takes place when these entities give up their economic and legal independence and build a new entity. Three different types of mergers generally exist: horizontal, vertical or conglomerate. (Schmusch, 1998, p. 11).

Those three different types of mergers can be characterized as follows (Tremblay/Tremblay, 2012, pp. 522f):

- A horizontal merger describes a merger with one or more direct competitor in order to expand the company’s operations in the same industry. Horizontal mergers are designed to produce substantial economies of scale and result in a decreasing number of competitors in the industry

- In a vertical merger, two companies which are operating in the same industry but at different stages of the value chain merge. On the one hand, this can e.g. be a company’s take-over of its supplier of raw material (backward integration of activities) but also, on the other hand, a take-over of its retailer (forward intergration of activities).

- A conglomerate merger involves companies engaged in unrelated types of business activities, i.e. their businesses are neither horizontally nor vertically related. Conglomerate mergers are the unification of different kinds of businesses under one flagship company. Those mergers aim at the utilization of financial resources, an enlarged debt capacity and also the synergy of managerial functions. In the case of impure conglomerates mergers, however, the two businesses are to a certain degree related, either because they sell similiar products but in different geographic markets or because their products are related to a certain extent, e.g. both companies produce different kinds of groceries.

An acquisition is “essentially the same as merger”, but the term is usually used in reference to a large corporation’s purchase of other corporations. It can be performed by a direct purchase or a merger agreement that involves the exchange of assets. In many cases, an acquisition is carried out in agreement with both sides, but there are also hostile takeovers, which mean that the firm targeted for acquisition disapproves of the merger.

3.2.2 Cross-border M&A

Cross-border mergers and acquisitions have long been an important strategy to expand business abroad. Due to technological developments and globalization, M&A activity sharply increased over the last two decades. They skyrocketed in the 1990’s reaching a peak in 2000 with the booming stock markets and the larger degree of financial liberalization worldwide, sharply declined in 2001 and 2002 and rebounded again with new developments in the world economy after 2003. Traditionally, developed countries, and in particular the developed countries of the European Union and the United States, have been the largest acquirer and target countries for M&A. During the 2003–2005 period, developed countries accounted for 85 % of the total USD 465 billion cross-border M&A, 47 % and repectively 23 % of which pertain to EU and US firms either as acquirer or as target companies. (Althaus et al., 2004, pp. 1ff)

Cross-border transactions pose bigger challenges for the executives and consultants involved than national mergers and acquisitions. Successful international M&A therefore require an extra portion of knowledge and assistance to all parties. On the one side, cross-border transactions conduce to achieving the strategic goals of the purchaser. On the other side, the seller can obtain a higher price as with a national transaction. (ibid.)

However, the following requirements are essential for successful cross-border M&A:

1. M&A Know-How

In contrast to large firms, an M&A transaction usually is an event that is not part of the everyday business for mid tier companies and often means a unique event in the history of the company. Therefore, the knowledge about the whole M&A process is either rudimentary or not at all existing in a company. Big companies, however, have their own M&A units, which can correspondingly elaborate transaction concepts and have the necessary knowledge about countries and different cultures. (ibid.)

30 TIPS ON HOW TO LEARN ACROSS CULTURES (14)

(Andre Laurent)

- 14. Across cultures, attribution errors occur in both directions: genuinely individual characteristics are wrongly labelled as cultural, and conversely cultural patterns are wrongly attributed to an individual’s personality.

In: SIETAR (Hrsg.), Keynote-Speech, Kongress 2000, Ludwigshafen

2. Understanding of other cultures

The entrance into a new region is accompanied by the overcoming of cultural obstacles. This requires a solid knowledge about the respective national culture and their specific characteristics. Assuming that the market conditions, competitive advantages on their own and major political, economic and legal conditions have already been considered attractive, it is also a vital part of a cross-border transaction to specifically comply with the following aspects: Fluent command of the transaction language (usually English), preferably basic knowledge of the language of the decision makers involved, familiarity with foreign cultures and the fundamental differences and different legal systems and tax systems, a sound knowledge of internationally significant accounting and valuation rules as well as know-how to efficiently integrate a foreign company. (van Gerven, 2010, pp. 44ff)

3. Involvement of middle management and key persons

Occasionally, the middle management and key employees of a company are informed about the pending takeover too late. Such an approach does not encourage the active commitment and the formation of new management teams. Especially in cross-border transactions, the start and the early involvement of the right people is vital. So-called kick-off-meetings and workshops have proved to be successful tools for the communication of basic information about the planned transaction. The work teams have to be merged in a way to enable the transition to start smoothhly in the acquisition phase and to be completed in the subsequent, comprehensive integration phase. In particular, the cultural and organizational integration often requires additional management resources. (Althaus et al., 2004, pp.1ff)

4. Inclusion of a cross-border M&A advisor

The management or a group, which is occasionally consulted, cannot simply handle the entire cross-border transaction. To be successful, it is advisable to involve a team composed of managers from different departments and an experienced M&A consultant. The consultant should accompany the process from the beginning to the end and have the following competences (ibid.):

- Access to global resources: International transactions are usually conducted under significant time pressure and expectation. Therefore, the rapid access to reliable and competent partners in all economically important markets and countries is a prerequisite. The customer will not accept if the M&A advisor must first establish own contacts in the relevant country. It is also expected that the members of an international M&A consulting firm know each other in person, have regular contact with each other and have already worked together on international projects. Their common understanding will have a positive impact on the course of the transaction. (ibid.)

- Identification of numerous contacts: For corporate sales, foreign buyers regularly pay a higher price than national prospects. It is therefore particularly important that many international contacts to prospective targets exist and can consequently ensure the optimization of value (the sale). An efficient global network of M&A professionals would perfectly cover the customer needs, which are identifying and contacting potential interested parties, information about transactions carried out country-specific developments in the industry, consulting on-site customer support and the involvement of local consultants. (ibid.)

- Collaboration with local consultants: For international transactions, it is imperative that – especially in the acquisition phase – local experts (lawyers, tax experts, accountants, banks) are consulted for special work (including Due Diligence, negotiation support, financing). Extensive contacts on a global scale facilitate the break-down of barriers in unknown cultures. (ibid.)

- Comprehensive M&A surveillance: For smaller domestic transactions it may be understandable that small and medium-sized companies consult with their lawyer, accountant or auditor only for specific services. The effort for the implementation of an international transaction, however, is often underestimated. An experienced M&A consultant will relieve the company’s internal project team and greatly optimize the entire transaction process, so that the managers can focus on other factors of success (commercial analysis, concept integration, communication, etc.). (ibid.)

The acquisition of an already existing company over a long period abroad is far more complex than a business expansion through the establishment of branch offices or subsidiary companies. Therefore, existing cross-border competences of the management are extremely helpful to the success of cross-border transactions (ibid.).

30 TIPS ON HOW TO LEARN ACROSS CULTURES (15)

(Andre Laurent)

- 15. To avoid wrong attributions, a paradoxical strategy is needed. When dealing with people from other cultures, as a starting point, make every effort to forget everything about culture and cultural differences. Try to meet the individual and its uniqueness first. Avoid categorizing. Concentrate on the individual. The cultural dimension will come next and soon anyhow.

In: SIETAR (Hrsg.), Keynote-Speech, Kongress 2000, Ludwigshafen

3.2.3 Reasons for M&A

There are several reasons why corporations are looking for external growth by merging with or acquiring other companies. Among a lot of factors, M&A are seen as supportive for cost savings through economies of scale and the realizations of synergies in order to increase the company value. Some of the most important reasons why companies consider M&A as a good deal are to be found in the following table (Hermann, 2008, pp. 6ff).

Tab. 3.1: Benefits of M&A

Source: Hermann, 2008, p. 6ff

| Horizontal | Vertical | Conglomerate |

|---|---|---|

| Increased market power | More control over quality and delivery of inputs | Gaining market power |

| Network externalities | Greater control over coordinating production flows through vertical chains | Efficient internal capital market |

| Leveraging marketing resources and capabilities | Monitoring supplier performance easier | Efficient diversification |

| Reduction of excess capacity | Contract disputes minimized | Bankruptcy risk reduction |

| Economies of scale and scope | ||

| Creating new capabilities and resources |

In the course of globalization, M&A have become a useful tool for corporations to expand their business activities to foreign countries. With the help of cross-border M&A, companies can utilize the advantages of internationalization. One benefit of going international by merging with or acquiring foreign enterprises could be to overcome barriers to trade and thus serving foreign markets within certain trade blocs. In those blocs, firms can distribute their products without paying tariffs. Another advantage of cross-border and cross-cultural M&A are cultural synergies. To develop cultural synergies in newly-merged companies, global business leaders must be well trained and skilled at understanding and resolving cross-cultural conflicts. At the same time, they have to enforce a cooperative, cross-culture organizational behavior in a multicultural environment. (ibid.)

Another reason is the realization of economies of scale through cheap labor in low-wage countries as well as lower energy costs or overhead savings. A diversification with the help of a conglomerate M&A can be seen as a useful strategy to spread risks. By acquiring foreign assets, the diversification potential cannot only be seen in the diversification of the product range but also in expanding into different geographical markets. Thus, in times of an economic down-swing in the home market, companies can still benefit from their foreign activities, as different countries and regions do not have the same business cycle and the same stage of development. Therefore, the risk potential of weak national markets becomes less. The prevalence of M&A and the importance of various factors that give rise to M&A activity vary over time. (Finch, in web)

3.2.4 Drawbacks

Although there are many reasons for M&A, the major drawbacks can certainly be seen in the high rate of failures after deals have been closed. Most transactions fail to deliver the expected positive results and significant costs related to the failure are a major concern to companies’ stakeholders. Most literature consults the so-called cultural clash to be the primary casual factor for the failure of cross-border M&A. As there are different values, beliefs, practices and attitudes between the different cultures, the new management must find a way to integrate culture into the corporate strategy. Thus, the top management has to set goals and lead employees in line with cultural beliefs and attitudes. (Hermann, 2008, pp. 8ff)

Other risks of cross-border M&A can be seen ingeneral risks of foreign business activities. One example could be political risks, like civil strife, revolutions and wars disrupting the activities in foreign countries. Another example could be fluctuations in the exchange rates between different currencies. (Hackmann, 2011, pp. 9ff)

3.2.5 The process of forming M&A

Pre-merger phase

Before the process of forming a new company is going to happen, a lot of issues have to be carefully considered. What are the benefits of such a project, what are the pros and cons, which risks have to be undertaken and which price has to be paid for such an undertaking are only a few questions that have to be addressed properly before a final decision can be made. In the pre-merger phase, the time frame for the integration and the planned development of synergies must be clearly marked out and it has to be discussed whether support from outside the company should or should not be asked for.

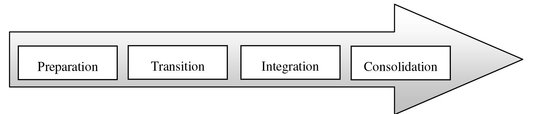

When the final decision has been made, the post-merger integration begins. Every integration process needs to be adapted to different situations. In order to understand the integration process properly it is useful to consider the four relevant phases. The following figure will give you an overview in connection with a general time frame.

Preparation phase

In business, planning is one of the major objectives in everyday operations. For M&A, planning is the key to success in the preparation phase. Meetings will be held, the top management is involved, interviews and surveys are carried out. As far as the pre-deal planning is concerned, a practical example will demonstrate which activities are necessary and which departments are involved.

Transition phase

During this phase the partners begin to work together. Plans are put into actions and integration teams are formed in order to develop detailed plans for the merging process. It is the time when troubles begin. The cultural dimension comes into play; cultural differences will now start to become obvious. Each party is convinced that their behavior is the right one. Gancel/Rodgers/Raynaud (2002, p. 127) wrote in this context: “The initial euphoria is replaced by a culture shock: a collision of values and beliefs that baffles and frustrates the individuals concerned.” The quality of communication and information will be negatively influenced. It is up to the integration team to work out a new and more detailed plan in order to safeguard the project. The newly merged companies are now confronted with cultural discrepancies. This is a dangerous situation when the project can actually fail.

Integration phase

At this stage, detailed strategies and plans are implemented as people start working together more comfortably and first synergies become apparent. Due to people’s natural suspicion and reluctance towards change, building true commitments to the new way of doing things takes more time. The old cultural profiles of the partners begin to play a less critical role, as people begin to agree on common values and build up a history that they will share. This is not only a result of some employees leaving the company because they could not or did not want to adapt to changes, while new employees joined the team. Nevertheless, it is of great importance to be aware that, at any time, operational integration is usually further developed than cultural integration. Technical aspects may follow a set up plan, and quickly start to work in functional ways. However, people’s attitude towards change is most likely to widen the time span of cultural integration (Gancel/Rodgers/Raynaud, 2002, p. 129).

During this phase, stability comes into the new organization. The overall goal has been reached, when all tools have been appropriately used and all plans have been successfully implemented. All operations involved in running the new organization will eventually be backed up with strength and stability. As a result, stakeholders begin to see clear evidence of the emerging synergies. Finally, the new corporate culture becomes deeper and deeper enrooted in the increasingly solid ground of the company (Gancel/Rodgers/Raynaud, 2002, p. 131).

Friendship and instinct

(Jeremy Williams)

Many Arabs have (or believe they have) special intuition or a “sixth sense” that guides them towards the correct decision in any matter. This can lead to sudden judgements and instructions that are difficult to dislodge, even in the face of new facts relating to the topic. Many Arabs will often trust their instinct rather than plough through a mass of boring detail. This special Arab sense may or may not exist (and there are many examples when Western “experts” were, in long term, proved quite wrong in their advice to their Arab principals). What is certain, in terms of judging people, is that almost all Arabs can quickly notice, and see through, false or shallow “friendship” sought or maintained simply to advance commercial or other activity. Be “genuine” in your friendship or relationship: don’t “pretend” with Arabs.

In: Don’t they know it’s Friday?, 2004, p. 66

3.2.6 Cultural Due Diligence

Definition of Due Diligence

The term Due Diligence is used for various concepts involving either an investigation of a business or person prior to signing a contract. It can be a legal obligation, but the Due Diligence will more commonly apply to voluntary investigations. A common example of Due Diligence in several industries is the procedure through which a potential acquirer evaluates a target company or its assets for acquisition. (Hoskisson/Hitt/Ireland, 2004, p. 251) The Due Diligence is the careful analysis, review and assessment of an object of purchase, especially before an asset deal. The investigation of the strength and weaknesses of the target company, as well as the determination of the risks, are the goals of a Due Diligence. The implementation extends to the review of the business documents and a survey among the management, among other things. There are many implementation phases, according to the specific purchase intention of the buyer. The purchasing price will depend on the outcome of this inspection. The Due Diligence is intended to be an objective, independent examination of the acquisition target. In particular, it focuses on financials, tax matters, asset valuation, operations, the valuation of a business, and providing assurances to the lenders and advisors in the transaction as well as the acquirer’s management team. (Angwin, 2001, pp. 35ff)

Importance of the Cultural Due Diligence

Next to the Financial and Tax Due Diligence, the Cultural Due Diligence should be of special relevance. Before and during every M&A-transaction, the cultural compatibility of all involved parties should be examined. Different business models, basic approaches, compensation systems, values, norms etc. could evoke serious problems in the case of international corporate mergers if their observation is neglected. The involvement of cultural investigations in mergers and acquisitions becomes increasingly important. Studies have shown that cultural coflicts were initiated when two business cultures had to merge and are one reason for the failure of business combinations. The Cultural Due Diligence methodically analyzes all business cultures involved. A business cultural analysis reveals cultural differences and their relevance and importance for the M&A parties. (Schneck/Zimmer, 2006, p. 593)

The Cultural Due Diligence should not play a secondary role, because it could also lead to a termination of the M&A negotiations. To a greater degree, there are more costly investigations avoidable if one assesses the barriers and differences in advance. Some consulting companies concentrate on culture management and cultural integration during corporate mergers, and have hence identified a market niche and new means of income in the traditional M&A business. The neglect of business cultures in the M&A process and the potential occurring problems of a following “culture clash” could endanger corporate mergers. Therefore, it would be beneficial if consulting companies generally extended their service package and made the Cultural Due Diligence an inherent part of the M&A process. (Schneck/ Zimmer, 2006, p. 587)

For the last years, a Cultural Due Diligence for mergers and acquisitions has been suggested, so that more and more careful inspection of the integrative business cultures have taken place. Behind that is the concept of analyzing the financial data as well as the business cultural compatibility beforehand. A Cultural Due Diligence is useful for analyzing the different beliefs as well as the different leadership philosophies. It is important to distill the real risk factors for the cultural integration and to entirely concentrate on them during the integration process.

The main idea of a Cultural Due Diligence is simple. You just have to find out how similar or different the merging cultures are. During a merger and acquisition the sense and purpose of the contrast intensification is to delimit the own culture of origin and to preserve it, so that the own corporate culture will not be destroyed. Whether the cultural integration would be easy or difficult can only be answered by the comparison of the two cultures and their apparent similarity or dissimilarity. It is not necessary to have vast objective differences to cause a redoubtable “clash of the cultures”. When you are faced with a possible threat from the outside like a merger or acquisition, people tend to band together with others of their ilk. During mergers or acquisitions, the concerns and distinction mechanisms on both sides are actually similar but can still separate them.

During takeovers, the staff and especially the executives of the transferred business try to explore the conditions of the “winner”. They want to find out if they have a chance in this new constellation. For the executives of the acquisitive company it seems reasonable to act dismissively and authoritatively towards the competitors. They want to show right from the beginning that the others have to quit the field or be satisfied with a subordinate place in the operating pecking order. The result would be that even without vast cultural differences the dynamic of the system would generate two polarized factions and would promote the “clash of the cultures”. The cultural integration stands and falls with the feeling of belonging. It is about having a place in the new organization where everyone feels accepted and contributes one’s share to achieve a common goal. Only if people feel accepted by the community, they can concentrate on their tasks and generate a full load output. As long as the people are unsure about their place and acceptance and fear to be a discriminated minority, they are under stress and are primarily concerned with their own interests and their situation, which will create difficulties. As a result, they will work badly together. (Berner, 2008, p. 85)

The central factor for the success or failure of the cultural integration is whether it is successful at conveying trust among the staff and executives, so that the people have a place in the new company, feel accepted and can show full commitment. (ibid., p. 91) The risk factors consisting of difficult compatible values, convictions and habits could be early recognized during a Cultural Due Diligence. (Steinle/Eichenberg/Weber-Rymkovska, 2010, p. 254)

The two biggest risk factors of the cultural integration are, on the one hand, the belonging and, on the other hand, the perceived meaningfulness of the future occupation. (Berner, 2008, p. 85) The merger syndrome describes all the feelings and behaviors, including suspicion, coordination problems, disorientation, loss of control and misunderstandings, which occur, when two cultures collide because of the different cultural perceptions. The company is strongly influenced by those problems, so that the daily business suffers and competitors profit from it. (Balz/Arlinghaus, 2003, p. 179)

To sum it up, cultural differences could definitely lead to a failure or collapse of a merger or acquisition und should therefore be analyzed in a Cultural Due Diligence.

Conduction of a Cultural Due Diligence

Diverse data collection procedures for the investigation of a corporate culture exit. For that, instruments mainly from the empirical social research are used, which are very helpful for investigating people’s opinions and attitudes. With the assistance of these instruments, it is possible to research the social phenomena and their cultural backgrounds. It is important to use the same tests, instruments and procedures in both companies to guarantee a high validity of the data. To ensure the comparability of the determined data, the analytical instruments should have fixed manuals and guidelines. Statements of the employees, internal documents as well as interviews of customers, shareholders and other persons related to the company should be included. A complete picture of the business cultures should be the result. The data collection is very important for the implementation of a Cultural Due Diligence, but it could lead to large difficulties. Sometimes, the top-management of the company does not give the permission to interview the staff or look into internal documents before the closure of the transaction. Fear to interrupt the peace in the company exists, because mergers involve concerns and a feeling of uncertainty among the staff. In this case, not all relevant information can be explored in the pre-merger phase. Consequently, certain analytical instruments can only be used or permitted during specific phases of the M&A transaction. (Schneck/Zimmer, 2006, p. 604) The following instruments could be used (Schneck/Zimmer, 2006, pp. 604ff):

- Document and Content Analyses

- Critical Event Analyses

- Observations

- Interviews

- Simulations

- Questionnaires

3.2.7 An evaluation of mergers & acquisitions

How good are companies at mergers and acquisitions? A survey conducted by KPMG (The initials stand for the founding fathers Klynveld, Peat, Marwick and Goerdele) shocked the business world in 1999. The findings say that only 17 percent of the examined mergers had led to an increase in the equity value of the companies after one year. Some 30 percent of the mergers created no value and 53 percent actually destroyed value (Kelly, 1999, p. 2–5).

According to Jahns (2003, p. 20) 60–70 % of all merger and acquisition transactions fail and do not achieve their long term growth objectives due to profitability losses of over 10 % during the merger process. Two years after a transaction the following developments were reported: 57 % of all “new” organisations suffered from enormous losses in their profitability, 14 % lingered with their original standard and only 29 % achieved an increment in their profitability.

Dielmann (2000, p. 478) has pointed to the fact that “one major reason for the failure of many mergers and acquisitions is the insufficient consideration of the human factor”. In 1999 top managers were asked and the findings show that the lack of internal communication (70 %) and the handling of cultural differences (46 %) had caused these problems (see Fig. 3.3).

Another study showed that 85 % of he managers regarded cultural differences in the leadership styles as the main reasons for the failure (Bertels/de Vries, 2004, p. 2). For Dielmann (2000, p. 478) the conclusion is quite clear:

“The most important thing is that the new organization has to give highest priority to the creation of a new corporate culture. The heads of the organization and the board of management do not only need to control the process of integration and lead the new organisation into a new continuity, but they also unconditionally have to live the new culture themselves.”

However, why is culture the leading factor for failures? One reason is a lack of awareness or blissful ignorance. Managers are simply unaware that the cultural dimension exists at all. Another possible answer is that, although they may be aware of the culture, leaders simply do not understand it well enough and therefore cannot assess the impact it could have.

Time-keeping – the biggest frustration?

(Jeremy Williams)

Probably all Westerners in the Gulf will quickly agree that the frequent inability of their Gulf colleagues to keep to time is the most significant of all cross-cultural aspects affecting their work in the Gulf. But many Gulf Arabs will comment that they are always available at any time and that access to them is simple. They may claim that it is only the unavoidable and unforeseen accident of other duties – such as those involving the family or friends – or unexpected duties placed necessarily on them by members of ruling families that draw them away from agreed meetings with Westerners. Westerners normally have no concept of the absolute duty that Gulf Arabs have towards family situations which are, in general, far greater than those undertaken, or expected, in Western society. “My brother telephoned and asked to see me, so I had to go to him; I am sorry I had to miss our meeting” is typical of a remark a Gulf Arab might make to a Westerner after a failed meeting i.e. genuinely believing that the explanation – because it involved a family member – would be understood, and failing to comprehend that for the Westerner such a reason would not be good enough. The Westerner would have been far less bothered if a phone call rearranging the meeting had been received, but the experience of almost all Westerners is that most Gulf Arabs do not reschedule meetings beforehand – they simply fail to appear when expected. “Time” is therefore a major area of culture clash.

In: Don’t they know it’s Friday?, 2004, p. 39

“A company’s culture is often buried so deeply

inside rituals, assumptions, attitudes, and values

that it becomes transparent to an organization’s members only when,

for some reason, it changes.”

(Rob Goffee)

3.2.8 The influence of culture on M&A – selected results of two studies

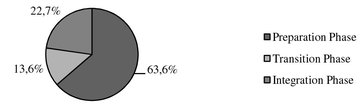

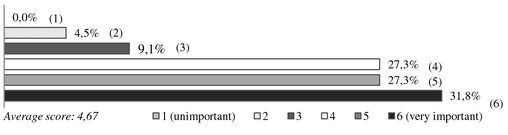

In 2011 a study concerning the influence of culture on M&A transactions was conducted by Carolin Boden, Elisabeth Guth, Nelly Heinze and Sarah Lang, students of Baltic Management Studies at the University of Applied Sciences Stralsund. The questionnaire was filled in by 22 consulting companies and M&A-experts from 14 different countries, which are specialized on various aspects of international M&A. Some results of the study can be found here.

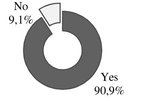

1) Do cultural differences often prove to be an obstacle?

2)Would you consider the intercultural training as sufficient in most cases?

3) When would you recommend starting with the training?

4) What is the most common reason for the failure of M&A?

5) How would you rate the influence of cultural misunderstandings on the failure of M&A?

Source: Boden/Guth/Heinze/Lang, 2011, pp. 75ff

Another study on culture and M&A was conducted by Amène El Mansouri, Laura Prestel, Nejma Samouh and Yang Wang, students of “Management Interculturel et Affaires Internationales” at the Université de Haute-Alsace, Mulhouse-Colmar. In this case, a questionnaire was sent to companies which had already conducted a merger or an acquisition. The following companies participated in the study: Abbey National-Banco Santander, Arcelor-Mittal, Gecina-Metrovecesa, Orange-France Télécom, Rhodia Chalampé-Slovay, Saint-Gobain/BPB and Wind-Weather Investment.

1) What cultural obstacles did you face during the M&A process?

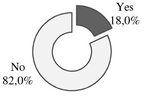

2) Did you get any intercultural training during the M&A process?

3) Do you think that intercultural management is important for an M&A company?

4) What are the most common reasons for a failure of M&A?

Source: El Mansouri/Prestel/Samouh/Wang, 2011, pp. 51

Both studies show that cultural aspects can have a significant influence on M&A transactions. However, the majority of participating companies did not offer any intercultural training. The lack of this kind of training was also among the most listed reasons for the failure of M&A. As far as the opinions of the consultants and experts are concerned, the result is even more impressive: cultural misunderstandings are on the top of the scale.

3.2.9 A practical example: a pre-deal planning by KPMG

Successful acquirers take the long term view and recognize that the cost of their investment in pre-dealing planning is minimal compared to the potential impact of failing to generate the desired level of return from the transaction. KPMG has developed a guide to pre-deal planning (Kelly, 2003, p. 5–8):

a) Be clear about strategic intent

An M&A is a tool to meet strategic objectives, not an end in itself. Even if the integration process runs smoothly, a flawed strategy will inevitably lead to serious problems. Be sure that the strategic rationale is translated into a shared vision (ideally with measurable targets) and communicated to all stakeholders. Management also needs to determine what is valued in the target.

b) Assess the top management team

Identify and involve the team who will be responsible for managing the new business. It will be important to:

- consider the role of the target company top team in the future plans of the business;

- consider whether between the two businesses there exists a management team capable of running the new, enlarged business. Often the management team needs external strengthening;

- determine how key executives need to be secured or incentivised;

- define succession and contingency plans as the departure of top team personnel from the target is common;

- define and communicate a process for selecting the management team;

- define any redundancy matters relating to the top team swiftly but be aware that the investigation process by its nature asks many questions and often results in a breakdown of trust, so it is ill-advised to make snap judgements about management during the pre-planning phase.

c) Determine approach to integration

Two key questions must be addressed during the planning period:

- To what extent should we integrate these businesses?

- What style should we use to carry out the integration?

The motivation behind much of the current M&A activity is based on the opportunity to achieve synergies from bringing businesses together. Typically, organizations underestimate the extent of integration they should be undertaking early on. However, failing to integrate the target sufficiently is responsible for much of the disappointment around the extent of benefits derived from a transaction. By the time they realize this is the case, the 100 day period is over or inappropriate messages may have been communicated to stakeholders.

In terms of style of integration, it is clearly valuable to learn lessons from past experience; however, a successful approach adopted in one case may not work as well when applied to another. At one extreme is a directive approach, based on a “just do it” mentality entailing minimal involvement from the workforce. This may be appropriate in low tech industries. At the other extreme, facilitative approach puts emphasis on managers to find solutions. It assumes a highly skilled workforce working to a high level agenda and assures implementation through involvement and “buy-in”. This can be appropriated in high growth markets. The decision on which approach to adopt may vary for different parts of the business (e.g. divisions, countries, functions) and is based on:

- quality of people;

- availability of resource;

- degree of risk;

- distance from customers;

- complexity of issues;

- access to best practice.

The approach requires careful consideration and evaluation during the pre-deal period to ensure the integration programme is tailored appropriately to the particular circumstances of your deal.

d) Involve the “right team”

Given the range of internal management and external adviser involvement, it is vital to appoint an Integration Director responsible for the transaction process as a whole. One of the teams within the programme will be that of the integration planners. It is important for that team to:

- include a mix of M&A experience and operational management capability. The role of the operational team is key. Initially the acquiring team, but later the operational staff of both businesses, can impact on the ability to deliver value.

Their knowledge of the business can:

- have an impact on the value/price;

- help you to plan for the 100 days; ensuring integration programmes are achievable;

- ensure buy-in to the integration plan;

- have continuity through the deal completion into the initial post-completion phase so that immediate benefits can be realized;

- be full time to enable them to give the implementation process their undivided attention.

e) Create the integration programme based on where benefits will be derived

Traditionally many of the original synergies will not materialize during integration due to:

- failure to test synergy assumptions,

- failure to recognize the role of the operational team.

It is therefore important to build a plan to identify benefits beyond those originally envisaged. Often these benefits are limited by prudence or city code rules. However, experience shows that 20% of integration activities will deliver 80% of the benefits, so it is advisable to focus on the projects which will create the biggest impact. Once benefit pools have been identified, it is important to build a plan to deliver them and to establish momentum in the first 100 days. At the planning stage, it is necessary to:

- ensure the process is underpinned and consistent with a common business vision /strategy;

- develop first action plans setting out what should be done to take control of the business;

- identify workstreams for the key benefit areas and identify work teams to deliver them;

- allocate tasks, timings, responsibilities, milestones and deliverables for the projects that have been identified;

- revisit plans on an on-going basis as information becomes available;

- plan to handle the overlap and interfaces between workstreams to avoid losing value.

f) Address cultural issues

Assess cultural differences between the acquirer and the target. Too often these differences are underestimated and yet they can undermine the 100 day programme as well as the longer term implementation. Ability to identify cultural issues will depend on the extent of access to the target pre-deal, but should cover:

- leadership style, management profile, organisation structure;

- working practices and terms & conditions;

- perceptions from the marketplace.

g) Develop a communications plan

Communication is a critical factor in the successful handling of M&As. Companies which are caught unprepared on deal completion find it difficult to reassure employees and other stakeholders. It is therefore important to produce a communications plan early on, before completion:

- the messages for the different stakeholder groups and the timing of their release;

- the process of cascading information through the organization is important, e.g. decisions on the mix of one to one, group meetings and written communication and the content of each will need to be addressed;

- the Day One communication programme is probably most critical of all; you only get one chance to make a first impression;

- how the press will be managed, the content of release and information packages and the points of contact;

- any immediate matters that will affect day to day business, such as the name to be used by the new organisation and how switchboard staff will answer the telephone.

“We regard the interplay among diverse cultures

as a strength and an opportunity

to boost creativity and productivity.”

(ThyssenKrupp Stahl AG)

3.3 Interview with Peter Agnefjäll, CEO of IKEA

Natalia Brzezinski spoke with Peter Agnefjäll, CEO and President of the IKEA Group since September 2013, about successfully doing business across cultures.

Brzezinski: IKEA is a global company, is it challenging exporting your values-based leadership model to stores and managers in other nations that may have different cultural values?

Agnefjäll: We need to work actively with our values and culture to keep them alive. Today, this is integrated in the way we recruit and work with people development. We actively seek people who share our values and recruit on values first and second on competence. For our leaders there is constant follow up regarding culture and values and we measure how well they communicate the values. Culture and values are also an integrated part of our development and performance talks for all managers and co-workers.

Brzezinski: In your experiences, what are the policies and practices that really work in promoting and retaining top female talent? What truly sparks change?

Agnefjäll: We are working with a set of tools that we feel work very well. One is the leadership commitment. We also strive to create an environment that encourages all competent coworkers who come from different backgrounds, for example can flexible work arrangements accommodate for individual life situations. Practices vary between countries for example in Japan we have a day care centre next to one of our stores and we have introduced paternity leave; both enabling more women to have a career. Several countries are trying out job sharing where two people share a manager position to facilitate for combining manager position with for example parenting during a period.

Brzezinski: […] How would you describe your leadership style and what works for you in empowering your employees, both male and female?

Agnefjäll: I am a believer in people and IKEA is a truly people and team oriented company. Our leaders appreciate working close together in a team with clear framework and clear goals, but we also leave room for freedom. I am enthusiastic so sometimes it is hard to let go but I try not to poke my nose into other people’s areas of responsibility. Delegating and relying on others by giving them responsibilities is part of the IKEA culture. At IKEA we give straightforward, down to earth people a chance to grow, both as individuals and in their professional roles. It is essential for our growth to develop our business through our people.

Brzezinski: What workplace trends or market changes are you seeing on a global scale, perhaps from the United States to China or India? Are your stores and corporate culture in the U.S. very different than the ones in Sweden or elsewhere?

Agnefjäll: We have been on the U.S. market since 1986 and in China from 2000. We do often find that our values are universal and that there are more similarities than differences between the different markets. When we enter a market, experienced IKEA co-workers work together with locally recruited co-workers there to support and ensure that the values and concept are clear. Now, when we will enter the Indian market we will follow the same approach.

In: Huffington Post Business Online, extract, 20/12/2013

3.4 Case Study: From foundering consumer goods factoryto cookware leader: A recipe for growth

When I. Smirnova arrived at the Demidovsky plant in Russia’s Sverdlovsk region fresh with a management degree in 1999, her boss challenged her to use her newly acquired skills to come up with a last-ditch plan to save the business from closure.

The factory had made scarce consumer goods during the Soviet period since 1947, and even produced a non-stick Teflon range of saucepans from 1982. But the work of its 650 staff –almost entirely low-paid women – was an after-thought to the aluminium plant next door to which it belonged, and it made losses year after year. “I brought all the employees together, and felt as though I had the whole weight of Russia on my shoulders,” she recalls. They were afraid that they would lose their social benefits, such as holiday camps for their children. I told them that to survive under capitalism, we need to be interesting for our shareholders and to the market.” With support from the owner, which since 2000 has been Sual, she has increased wages 2.5 times for a slightly smaller number of staff, and turned the factory into a profitable venture, which now sells cookware throughout the country.

The secret was to give her autonomy. “When 99 per cent of management time was focused on the aluminium factory, we may have had a good product but we were losing more than $ 100.000 a month,” she says. We started to calculate our production costs.” Most savings came through more efficient techniques, sharply lessening waste. She is no longer required to use supplies form the aluminium plant next door, and has bought from Sual’s competitors at home and abroad.

She has also instituted tough quality control. With staff paid by results, she docks up to 20 per cent for rejected saucepans. Late last year, she won the right to use Teflon’s platinum coatings, allowing her to launch a new luxury range of pans.

Ms. Smirnova has retained some Soviet-era practices, including quarterly employee awards, mixed with profit-sharing and management training for a dozen senior executives in her team. She has recently opened a chain of shops to market the products.

One challenge has been overcoming Russian suspicion of domestically produced goods. So she launched the English-language brand, Scovo. She has adapted to local habits, including a preference for the colors red and yellow; detachable handles because Russians like to use saucepans in the oven; and the importance of longevity.

Jack, A., in: Financial Times, 11/02/04, p. 8

Review and Discussion Questions:

- Which were the challenges Ms. Smirnova had to master in the beginning and during her work?

- What is her philosophy concerning the salary policy of the company?

- How did she succeed in combining old traditional structures with highly new management principles?

- Which key qualifications are necessary to do such a good job and what do you think about her academic background?