6

ADD and Personality Type at Work

In this Chapter

This chapter emphasizes the use of the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) to understand the interaction of personality and ADD and to help adults with ADD make career choices based on their personality type as it interacts with ADD traits.

The Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI)1 is a useful tool for assessing basic personality traits and their interaction with ADD. Until recently, very little attention was paid to the MBTI in connection with ADD. Although there is now growing interest in the uses of the MBTI with ADD, only limited research has been undertaken. What is written in this chapter is based on my clinical experience over the past several years, in administering the MBTI to individuals during both assessment for ADD and as a part of ongoing treatment for adult ADD.

This chapter describes how your personality preferences, as measured by the MBTI, interact with ADD and emphasizes how a knowledge of your MBTI personality type can be essential to understanding your ADD behaviors in the workplace, to formulating an appropriate treatment approach, and, to making wise career decisions.

ADD is Not a Personality Type!

Just as people with ADD come in all shapes and sizes, they also come in all personality types. In reading descriptions of individuals with ADD, it is tempting to conclude that ADD is a personality type, that people with ADD are very active, talkative, impulsive, creative, and terribly disorganized. These adjectives describe some adults with ADD, but anyone who has worked with adults with ADD knows that there is tremendous variation among them. You may have had the experience of reading books on ADD that described you to a tee. These books are describing the ADD traits that many adults with ADD have in common, traits you recognize in yourself. It is important to realize, however, that such books narrowly address ADD and ignore equally important non-ADD personality traits.

Because we are still in the early stages of understanding and working with adults who have ADD, the variations among them, caused by differences in personality type, have been all but ignored. Some adults with ADD are talkative extroverts while others are quiet and private. Some are hyperactive, others are virtual couch potatoes. Some are highly impulsive while others tend to be vague and indecisive. Some are highly intellectual, but many others disliked school and gravitated toward more active pursuits. What all these people share in common is some combination of core symptoms of ADD. This chapter will emphasize individual personality differences among people with ADD and will discuss how those differences interact with certain ADD traits to influence work functioning.

Although your ADD symptoms may play a very strong role in your life, you are much more complex than a list of ADD symptoms. By taking a measure of your personality traits and thinking about them in combination with your ADD, you will have a more complete picture of your strengths, weaknesses, interests, and preferences. Taking all of these factors into account, you will be much better able to find a good job or career match for yourself.

A Brief Description of the MBTI

I have used the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) as a measure of personality type for several reasons. It is brief, widely available, and inexpensive to administer, and it has been studied extensively in relation to job satisfaction and career match.2 The MBTI is also preferable to many other psychological tests of personality because it measures personality preferences in a nonjudgmental fashion, emphasizing personality preferences, not problems.

The MBTI was developed based on the personality theory of the well-known psychoanalyst Carl Jung, who believed that individuals have certain inborn traits that form the basic building blocks of their personality.3 Jung believed that these traits are fundamental and lifelong but that they can develop and change in certain respects. Interestingly, as neuroscientists learn more about the neurobiological basis for personality traits, we are now beginning to see scientific evidence to support Jung’s belief that people are born with different personalities.

Understanding MBTI “Preferences”

According to the MBTI people vary according to four pairs of “preferences”:

Let’s take a look at each of these eight preferences in order to understand how they are defined according to the MBTI.4

Extroversion versus Introversion

Extroverts (E’s) are people who are energized by interaction with others and actively seek their company. Being around people is life’s blood for the extrovert. People who are strongly extroverted may feel lonely and isolated when forced to engage in solitary activities. They often prefer verbal over written communication, and they seek discussions with others in making decisions. They tend to relate to a broad range of people instead of maintaining only a few in-depth relationships.

Whereas extroverts are social and are oriented toward the external world—they live in a world of “we”—introverts (I’s) inhabit a more private, internal world. Introverts tend to recharge, or reenergize, themselves in isolation from others. Social interaction, especially with groups or with people who are not intimates, is energy draining for introverts. Although a certain amount of interaction is necessary within the course of a day, introverts are prone to close the office door, to wish the meeting were over, to turn off the telephone, and to want to leave the party early. Their energy level becomes depleted after prolonged interaction with others.

Different Problem-Solving Styles

Introverts and extroverts differ in problem-solving style. Introverts are drawn more toward activities that require narrow focus and concentration. They are prone to turn inward when making a decision and to announce their decision to others after they have reached their own conclusion. Even when engaged in problem solving with others, an introvert is likely to mull things over before discussing the matter. By contrast, many extroverts begin to develop their ideas as they engage in discussion and dialogue with others. For extroverts, the very act of communicating with others often sparks ideas that haven’t yet occurred to them.

Cultural Bias Toward Extroverts

In the United States, in particular, there seems to be a strong cultural bias toward extroversion. (Introverts not only have to face this social bias against their type but also find themselves outnumbered 3 to 1 in the general population.) Introverts may be seen as withdrawn or lacking in social skills. Because of this cultural preference, many introverts (intentionally or not) try to respond to the MBTI as if they were extroverts. In fact, many introverts spend most of their lives attempting to behave in an extroverted fashion, trying to suppress introverted tendencies.

For example, one business executive who answered the MBTI as an extrovert protested when his examiner suggested that he was more likely an introvert; he insisted that he was seen as a genial, outgoing person at work. This “I in E clothing” made the mistake many people do, namely, confusing extroversion with social skills. Like many introverts, he had developed excellent social skills. He was well liked and was highly regarded as an executive. Unlike a true extrovert, however, he tended to yearn for time when he could close his office door to get some work done and he typically spent his evenings in quiet isolation to recover from his energy-draining people- filled day.

Appreciating the Powers of Introversion

If you are an introvert, understand your “I” tendencies and celebrate them! Don’t try to join the E’s of the world in the erroneous assumption that introversion is something to change or hide. I’s who try to force themselves into the shoes of an E won’t enjoy walking and will probably get blisters! Accepting your introversion will lead to a much more satisfactory choice of career. It is the I’s of the world who are able to sit and focus in order to write, create, learn, invent, and accomplish.

![]()

An extrovert uses his answering machine to catch calls while he’s out.

An introvert uses his answering machine to screen calls when he’s in.

Just as the majority of people are extroverts, most (approximately 75% of the population) have a preference for sensation as opposed to a preference for intuition.5 Those who prefer sensation, the S’s, live in the world of real, touchable, practical things whereas those who prefer intuition, the N’s, live in the domain of ideas and innovations. Another way to express this difference is to say that S’s live in the world of the actual while N’s focus on possibilities.

S’s Emphasize Hands-On Experience

S’s place the strongest emphasis on their experience, on what has actually happened. The nickname for Missouri—the “Show Me” State—must have been inspired by a group of S’s! Just like Missourians, S’s want to be shown the actual proof of things. They trust their own experience and pay the greatest attention to their surroundings, noticing details, collecting facts, and making concrete plans. Because S’s live in the world of things, they are natural-born shoppers. An S will likely read the newspaper ads for sales and will be the best source of information on where something can be bought for the best price.

N’s Live in the World of Ideas

N’s, on the other hand, live intuitively; they think of grand schemes, of possibilities, of the future. N’s are attuned to the creative, the imagined, the not yet actual. For an S, the N’s of the world may seem a bit flighty and impractical, dreamers who are always off in the clouds, who ignore the day-to-day requirements of life. N’s in turn may view S’s as unimaginative, plodding, and aware only of the boring, repetitive daily grind.

S’s and N’s form a Powerful Team

S’s often make good planners and managers; they pay attention to the details of what has occurred and what needs to be taken care of next. N’s make good creators, visionaries. A company with an N at the helm will always be moving toward the future, developing innovations, seeking new markets, and expanding in unexpected directions. The actual execution of these grand schemes is best carried out by S’s, however. A company with an S at the helm will be more solid and practical, with an eye on the bottom line and on competitors, but with little sense of direction other than an impulse to continue to do whatever it has done best in the past.

Of all the contrasts between personality preferences, the S-N difference is considered the greatest. It is almost as if S’s and N’s speak different languages and have difficulty in translating from one to the other. However, if this translation succeeds—if the two can learn to work together, respecting and understanding their differences—an S and an N can prove to be an unbeatable team!

![]()

An N Expands Life’s possibilities.

An S Makes the Possible Actual.

Thinking Versus Feeling

Thinkers (T’s) approach decisions from a detached, analytical, logical position. They value justice perhaps more highly than compassion. Feelers (F’s), on the other hand, make decisions in a more subjective manner, that is, by responding with empathy and trying to consider extenuating circumstances. For example, when someone has broken a rule, a T is likely to impose a standard penalty whereas an F would, as if by reflex, consider the circumstances that led to the infraction. The T might say, “He has to pay the price for what he has done,” but an F might add, “Yes, but he’s never done anything like this before, and he was under tremendous stress when this happened.”

This thinker-feeler dichotomy is the only set of preferences that shows a slight gender-related bias: Approximately 60% of women are F’s whereas approximately 60% of men are T’s.6 T’s and F’s can work together with great complementarity inasmuch as good decision making requires that both the thinking and the feeling aspects of a question be considered. Of course, we are all capable of considering both T and F aspects of questions, but people generally tend to have a preference in one direction or the other.

People Versus Production

Both T’s and F’s are capable of experiencing strong emotional reactions to events, but since F’s are more likely to openly show their emotions, they are usually seen as warmer and more compassionate than T’s. The higher one goes in the management hierarchy of an organization, the more likely one is to be a T. It may be that T qualities are necessary to guard the interests of the organization against the multiple competing needs of the employees. The T keeps an ever-vigilant eye on the bottom line. It may be just as true, however, that Fs are rare in upper management jobs because such positions of leadership, which are so detached from personal involvement with people, are not attractive to them.

![]()

T’s think with their head.

F’s think with their heart.

Judging versus Perceiving

The words judging and perceiving can be easily misinterpreted. It is a common error to think that “judging” means “to be judgmental.” A better way of distinguishing judgers (J’s) from perceivers (P’s) is to think of the difference between “defined” and “open-ended.” J’s are result oriented and seem to have a work ethic. They want to get the job done, to make a plan, to meet the deadline. P’s, on the other hand, have more of a play ethic. They don’t see the same value or urgency in accomplishing work. They feel much more strongly that work should be enjoyable, and they are likely to seek ways to avoid those tasks that are not enjoyable.

Deadlines

One of the most observable differences between J’s and P’s can be seen in their responses to deadlines. For J’s, a deadline is a serious limit that should be met. J’s meet deadlines and expect their coworkers to meet them as well. For P’s, a deadline is seen as more of a marker that can slide. For some P’s, a deadline can even be seen as a signal to begin a project rather than a time to complete it! (This P preference can easily be mistaken for the procrastination patterns found in adults with ADD. However, there is an important difference: Whereas P’s prefer to operate in that fashion, many adults with ADD feel almost helpless to work against their tendency to procrastinate and feel frustrated by the pattern.)

Decisions

Another major difference can be found in decision making. J’s, who like order, plans, and closure, tend to feel a sense of unease or agitation until a decision is made. “Let’s figure out what we’re going to do and make a decision,” a J would say. Once a decision is made, the J feels more relaxed and secure. This drive or sense of urgency to make decisions or to settle issues can sometimes lead to decisions that are made too quickly, without gathering enough information. P’s, by contrast, have a great tolerance for ambiguity and are quite comfortable considering all aspects of a question. P’s are always happy to wait before making a decision. “Who knows? Perhaps new options will emerge that I didn’t recognized earlier,” a P would say. Whereas a J feels relief after a decision is made, this type of closure often causes the opposite reaction in a P. “If we decide now, we may be closing off other options that could be better,” a P would argue. “Why don’t we just keep thinking, talking, and gathering information a bit longer?”

![]()

J’s want plans to come together.

P’s want plans to hang loose.

MBTI Types and Mistyping

In order for this chapter to be most useful for you, you will need to obtain an accurate measure of your MBTI personality type. You may have already taken the MBTI. Several million people take the MBTI each year! If you have taken it, the primary concern is whether you received an accurate measure of your type. If you are correctly typed, the MBTI can be enormously informative and useful in considering career concerns.

The reader should be aware that it is quite possible to take the MBTI and receive incorrect results. One man spoke with great mistrust of the MBTI, saying that he had taken it several times and had received a different personality type each time. How is this possible? The MBTI is not magic. It is simply a way of organizing and interpreting your responses. “Garbage in, garbage out” is the rule that applies here. To be typed correctly, you must answer questions according to your true preferences, not according to how you think you ought or are required to behave and not according to your mood of the moment. People may be typed incorrectly if they have a job or lifestyle that requires them to behave very differently than they would naturally choose to behave. To be accurately typed, you must respond to the MBTI according to your true inclinations, even though the demands of your daily life may require you to behave otherwise.

Mistyping in the Business World

People who take the MBTI as part of a workplace exercise may consciously or unconsciously answer questions in accordance with the values of the institution or in response to perceived social pressures. For example, some people in the business world may feel pressured to behave in an extroverted fashion even though by nature they are more private. Moreover, men in general (and perhaps especially those in the business world) may feel a strong social pressure to be logical rather than emotional. Thus, men who are truly “feelers” may respond to questions on the MBTI in a way that types them as “thinkers,” just as true introverts may respond in a way that types them as extroverts. Moreover, as women make efforts to reach upper-level management, those who are “feelers” may also be tempted to misrepresent themselves as “thinkers.”

Mistyping in Periods of Personal Change

Another source of mistyping can occur when a person is in counseling or is going through a midlife crisis, a divorce, a career change, or any other major life transition. These are all generally situations of internal turmoil and change. During such times people may try to “become” different. As they experiment with different ways of feeling and responding, they may answer the MBTI accordingly.

Do Personality Types Change?

According to Jungian theory, our basic personality preferences are inborn and don’t change throughout our lifetime.7 This does not mean that we cannot make changes or improvements in ourselves. In fact, many people in their middle years begin to develop other aspects of their personality. For example, extroverts may begin to develop their introverted side by taking up more solitary activities. Thinkers who have spent their careers focusing on the impersonal world of things may begin to learn how to express their emotions more openly. These changes are very healthy and result in a more balanced life, but they don’t result in a basic change in personality type. The situation is a bit like that of right-handed people who learn to eat with their left hands; although they can learn to do it, they will continue to have a strong preference for their right hands.

Learning Your MBTI Type

The best way to be typed is to take the MBTI by a trained professional who can score and interpret the results for you. If you are currently in counseling, your psychotherapist or counselor may be able to administer the test. If such testing is not readily available, however, there are short forms of the MBTI in a number of books written on the subject. You can find these books listed in the Resources section at the end of this book.

MBTI Preferences Versus ADD Tendencies

There is an important distinction to be made between the traits measured by the MBTI, which are personality preferences, and the symptoms associated with ADD. When Carl Jung developed his theory of personality, he attempted to describe the inborn personal preferences of individuals. According to Jung, each individual is born with these preferences and is most natural and comfortable in life when he or she behaves in accordance with those preferences. This set of preferences should not be confused with behavior patterns or tendencies associated with ADD. ADD traits are not due to personal preferences. They are the result of neurobiological factors (i.e., neurochemical and perhaps structural differences in the brain) that make certain cognitive processes much more difficult. For example, a person can have a strong tendency to stutter, but he or she is unlikely to have a preference for stuttering. The same kind of distinction can be made for many ADD traits.

Some professionals who are knowledgeable about the Myers- Briggs personality types but who are not experts in ADD sometimes confuse preferences and tendencies. For example, among certain MBTI personality types there are individuals whose preference is to be active and impulsive with little tolerance for detailed, mundane work. Such a person might be mistaken for one with ADD. In fact, there are those who mistakenly believe that ADD is a personality type rather than a neurobiological disorder. In a study of several hundred schoolchildren, however, the MBTI personality types that might be mistaken for ADD were found slightly more often among non-ADD students than among those with ADD!8

Although people with ADD come in all personality types, it is certainly possible for them to have personality preferences that are consistent with certain ADD traits. When personality preferences and ADD tendencies coincide, the result is an intensification of both! Double trouble!

![]()

Add strategies must Fit your personality

When MBTI Preferences Combine with ADD

I have discussed the eight MBTI preferences without regard to ADD. In this section I will attempt to examine the ways that MBTI preferences interact with ADD patterns, focusing in particular on the ways they interact in the workplace environment.

Extroverts (E’s) with ADD

The hyperactivity of an adult ADD extrovert is likely to be manifested by hypersociability. It’s likely that he or she was the schoolchild who was constantly talking in class. For the hyperactive, extroverted adult, people are likely to be one of life’s major distractions. Extroverts (E’s) are drawn to people to recharge, to discuss, and to problem-solve. When an E is also ADD, these discussions are likely to wander off the track, extend in time, and lose their effectiveness.

Problems with Isolation

Solutions for ADD-related problems need to be modified according to MBTI preferences. For example, one man, an E with ADD, was highly distracted by conversations and by people walking by in the hall near his office. His therapist suggested that he shut his office door periodically to decrease these distractions. Because the man was such a strong E, this solution was unworkable for him. With his door shut he found that his productivity became even worse! He felt isolated and was so curious about the bits and snatches of conversation he could overhear through his closed door that these conversations became even more distracting than before. A much more effective solution for him was to “time-shift” his hours. He began arriving at work at 7:30 A.M., which allowed him an hour or more of uninterrupted time to do paperwork, check e-mail, and organize his day before his coworkers began arriving.

Hyperverbalizing

E’s with ADD need to guard against hyperverbalization. One man who sold technical equipment found that his major problem in sales was talking his client’s ear off. He made some progress in checking this tendency by making brief notes of the points he wanted to make before calling each client. For initial calls he developed a script that helped keep him on track but with which he allowed himself some latitude. He also used timers for himself and set the goal of limiting client calls to 10 minutes.

E’s who have unwittingly acquired jobs more suited to introverts (I’s) may tend to prolong meetings, to socialize at the water fountain, and to infringe on the time of others because of their hunger for interaction. Those with ADD are even more likely to become caught up in such nonproductive behavior and may be misperceived by their boss or coworkers as “goof-offs.” If you find that these are your tendencies, you should consider shifting to a job that requires people interaction. This same energy and drive to socialize, which can be seen as work avoidance in some jobs, can benefit you greatly in a people- oriented job.

Introverts (I’s) with ADD

What happens when ADD is combined with introversion? One of the risks is that the preference of introverts (I’s) to be alone will conflict with the ADD need for external structure. If a person with ADD is isolated for significant portions of each day, it is quite easy as for him or her to drift off the track and not realize that this has taken place. One introvert (I) with ADD learned to cue himself to keep on track. He set goals for himself at the beginning of each day and estimated an approximate time period for each task. He then found it helpful to set a timer to sound every half hour as a cue to check his focus and his progress.

Prefer to Communicate in Writing

E-mail is a wonderful invention for I’s. One I with ADD found that it was helpful to communicate frequently with his boss by e-mail as a means of building structure and receiving feedback. He set weekly goals for himself and sent them to his boss (down the hall) by e-mail. At the end of each week he e-mailed his boss a progress report. They met face-to-face twice monthly. E-mail allowed him to minimize direct interaction but, at the same time, to benefit from external structure and guidance.

I’s report that they frequently feel overwhelmed by too many interruptions or too much verbal interaction. They become flooded or overwhelmed with stimulation to the point that they shut down. Again, e-mail can provide a solution to such flooding, because it can allow efficient communication without overloading the verbal interaction circuits. Some Fs with ADD have carefully arranged to work at night to avoid overstimulation. One I with ADD, who was very sensitive to stress and overstimulation, arranged his workday so that he could arrive home before rush hour and complete phone calls and paperwork from the peace and quiet of his home.

Sensers (S’s) with ADD

What happens when those who prefer sensation (S’s) have ADD? S’s are practical, active, and focused on the world of things. An S with ADD may be especially prone to start far too many projects and to constantly find him- or herself in the middle of incompleted renovations and repairs. An S with ADD may shop compulsively or may pick up many hobbies, which they drop as they pursue their next interest. They are likely to buy all the latest equipment for each new hobby, only to leave all these acquisitions in disarray as they move on to something else.

Surrounded by “Things”

How does the combination of ADD and this trait translate into the workplace? The same patterns can be found at work: a tendency toward great physical disorder, toward the acquisition of too many things, and toward impulsive spending and unrealistic budgeting. S’s with ADD are the inventors of the world; they are constantly tinkering, building, adding on. These tendencies can be a great asset if they are managed, but all too often S’s with ADD live surrounded by objects in midcompletion or midrepair.

S’s with ADD may be especially prone to become lost in the details of a project. For example, one man decided to make improvements in the daytimer system he used to help him plan and organize. He became completely engrossed in this project, developing special color coding systems, huge computer printouts, and intricate systems of symbols, meanwhile never putting his time-management program into effect.

S’s with ADD often need a non-ADD colleague to help them reach closure. When they are teamed with someone who can provide boundaries and limits their practical solutions can be quite creative and valuable to the organization.

Intuitives (N’s) with ADD

People who prefer intuition (N’s) and who also have ADD have the potential to be among the most creative and prolific people in the world—if their energy and interests can be harnessed. N’s live in the world of theories, ideas, and innovations. Unlike the innovations of their S counterparts, the innovations of N’s are not of the concrete “build a better mousetrap” variety but are more likely to concern the abstract themes of art, philosophy, educational theory, or government policy. N’s with ADD often report that they live with a flood of ideas and associations and that they tend to be highly distracted by their own internal world.

Drowning in a Sea of Ideas

One N with severe ADD, a highly intelligent man, reported with enormous frustration that he wanted to write a book for others like himself but found that he couldn’t organize and develop his thoughts. Although he had developed a huge list of random thoughts and associations over the course of several years of intense effort, he was unable to combine these into a format he could communicate to others. Another N with ADD, a man whose organizational problems were less severe, described his professional life as very satisfying but constantly stressful. He found that he was interested in a huge range of topics and was unable to realistically assess the demands of his current commitments before taking on another tempting project. As an adult with ADD he also struggled with procrastination and invariably put off papers and reports until the last minute.

Visionaries in Need of a Plan

In the workplace, N’s can be great leaders and visionaries. However, an N with ADD at the helm of an organization is likely to lead the entire organization into his or her world of unrealistic plans, overcommitment, and frequent crises created by poor planning and procrastination. Team up such an N with a non-ADD S, and many more of his or her ideas will bear fruit!

Thinkers (T’s) with ADD

When ADD occurs in those whose preferred style is for thinking over feeling (the T’s), the result is sometimes a combination of troubling interpersonal tendencies. Thinkers (T’s) prefer to deal with nonpeople issues: technology, profit, efficiency, or procedure. Their emotional, empathie side is much less developed. While some T’s may be good observers of human reactions, they are not prone to respond in a fashion that engenders closeness or understanding. Many people with ADD also have difficulty in reading social cues and emotional responses. It is as if their engine is running so fast (i.e., they are so preoccupied with their own thoughts and activities) that there is little time or energy left over to expend on people. When a thinking preference is combined with ADD, problems with people skills can be doubly intensified.

Missing Social Cues

When ADD traits of impatience and low frustration tolerance are combined with a T’s lack of attention to the feelings of others, there may be significant interpersonal problems on the job. Such people may be both difficult to work for and difficult to manage or supervise. If they are extroverts, they may be especially prone to talk nonstop and to be oblivious to the effect they are having on others. If they are introverts, their attempts to escape from the demands of interpersonal interaction may make them respond to people in a way that suggests indifference or annoyance.

Need to Build Social Skills

Social skills are likely to be a major difficulty for T’s with ADD. They will do well to team themselves closely with an F who can temper their reactions and can give them feedback about their effect on co worker s.

Feelers (F’s) with ADD

Feelers (F’s) with ADD are in a better position to develop good social skills. While T’s with ADD have a doubly influenced tendency to misread or overlook social cues, F’s with ADD have a tendency to be tuned in to the needs and feelings of others. This tendency gives F’s with ADD the means to counteract some of the interpersonal problems sometimes caused by ADD. For example, F’s with ADD may still blurt out something in a blunt or undiplomatic fashion. Their built-in social radar, however, will quickly tell them that they have overstepped the bounds of considerate behavior, thus giving them an opportunity to apologize and to “mend fences.” One woman, an F with ADD, reported that she was always having to “sweep up the pieces” after she had unintentionally upset someone. In fact, she consciously developed a charming, self-deprecating, and outgoing manner in order to compensate for unintentional faux pas.

Emotionality

F’s with ADD may find that their emotional and interpersonal reactions are intense, because their ADD traits toward overemotionality combine with their emotional sensitivity. Whereas a T with ADD may have fairly thick skin and may be somewhat oblivious to the negative reactions of others, F’s with ADD, by contrast, are likely not only to be aware of others’ hurt feelings but to experience such feelings themselves. Some F’s with ADD (more often female, though not always) may feel that they are on an emotional roller coaster, with strong tendencies toward tears, anxiety, and depression.

Intense Relationships

The emotional intensity of F’s with ADD in combination with their social sensitivity may also lead them to have intense intimate friendships and love relationships. This is in marked contrast to T’s with ADD (more often male), who may be emotionally unavailable and may have relatively few relationships with others. F’s with ADD, if well matched to their careers and jobs, can use their strong awareness of others to advantage, in sales, public relations, and in any other type of work requiring people interaction and sensitivity. Stress can be the Achilles’ heel for F’s with ADD. During high stress their heightened sensitivity to others may lead to overreactions and less effective functioning.

Judgers (J’s) with ADD

Judgers (J’s) with ADD are in a battle with themselves. Owing to their strong preference for order, closure, and predictability, J’s tend to be frustrated by their ADD. The disorganization caused by their ADD is at odds with their built-in preference for order. Their battle has both positive and negative consequences. If the resulting frustration is extreme, it can result in self-rejection, low self-esteem, and depression. If the frustration is mild, it can result in the development of effective coping techniques.

Tendency Toward Rigidity

In extreme cases, J’s with ADD may develop patterns that can be misunderstood as obsessive-compulsive tendencies. In their attempt to gain control over their uncooperative ADD brains, J’s may develop numerous rituals and habits to which they adhere rigidly. When J tendencies and ADD traits are both strong, the degree of rigidity may become extreme, causing problems for the J in living and working with others.

Compensate Well for ADD

When J tendencies are less pronounced or when the ADD traits are less severe, J’s with ADD have a great advantage over P’s in compensating for ADD patterns. Often, even without the assistance of others, J’s naturally develop behavior patterns or habits consisting of techniques to combat absentmindedness, to cope with distractions, to stay on schedule, to meet deadlines, and so on. Typically, J’s with ADD eagerly adopt all the coping techniques that come to their attention, since suggestions to create and maintain order are highly compatible with their own internal drives. These drives constitute their great strength: If they can moderate their frustration and their negative evaluation of themselves when their ADD breaks through, J’s have a great capacity and desire to compensate for their ADD.

Perceivers (P’s) with ADD

Perceivers (P’s), on the other hand, can suffer from what might seem like an excess of comfort with their ADD! ADD patterns may be more irritating and troubling for those who live and work with P’s with ADD than for the P’s with ADD themselves! This is because P’s (with or without ADD) by nature prefer to live in a less ordered, defined, predictable fashion. When their natural preference for spur-of-the-moment living is combined with the impulsivity of ADD, a volatile combination can result. Unlike J’s with ADD, P’s have no brakes—only accelerators. Thus, P’s with ADD may feel it is entirely justified to change plans at the last moment if they have just been inspired by a new idea or motivated by an impulse to do something more desirable. Their surroundings are likely to reflect the fact that they live at the highest level of chaos, with little or no organization among their papers and belongings.

Need for a Tolerant Environment

P’s with ADD may experience more difficulty than other personality types in finding a workplace environment that can tolerate their disorganization and appreciate their gifts. One P with ADD, for this very reason, started his own small advertising agency. Being the boss, he answered to no one. When his assistant arrived promptly at 8:30 each morning, she often found her boss asleep on the carpet, where he had crashed after working all night. Similarly, after working nonstop on a project, he felt free to take a day or two off, even midweek. By working for himself he was able to create a work life that was compatible with his strong P tendencies to follow the ebb and flow of his energies.

Need for Help with Structure

While P’s with ADD can be tremendously creative, effective people, they (perhaps more than other ADD adults) have great need of organized non-ADD persons to help them maintain some degree of order in their work lives.

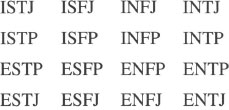

MBTI Personality Types

Through combining the eight basic preferences described in this chapter, the MBTI classifies a person according to sixteen personality types:

I have talked in broad strokes about the eight preferences of the MBTI1 and how these preferences may interact with ADD. In reality, however, the picture is far more complex than this. Each person has four preferences, which interact with one another. ADD traits complicate the issue even further. For example, an extroverted P with a preference toward feelings and an introverted P who is a logical, analytical thinker are going to be affected by their ADD very differently.

It is far beyond the scope of this chapter—it could indeed be a book in itself—to talk of each personality type and its potential interaction with ADD. There are many excellent books written on the subject of the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator, some of which are listed in the Resources section of this book. Reading these books, especially those with a focus on the MBTI and careers, and thinking of the ways that personality type and ADD interact, which I have only touched upon in this chapter, can be helpful to you in making career choices or changes.

The most important message to take from this chapter is that you are much more than an adult with ADD. It’s certainly very important to be aware of ADD traits and tendencies, but don’t lose sight of the fact that you are unique and complex. Solutions to your ADD problems need to be custom-tailored to you, taking your personality preferences into consideration. Keeping your personality preferences in mind, in combination with ADD issues, will help you make a choice that makes sense for you, not just for your ADD!

1Note: In several subsequent chapters you will find many references to aspects of the MBTI. If you are not familiar with the MBTI, you may find it helpful to refer back to this chapter and to read some of the books on the MBTI listed in the Resources section at the end of this book.