Finding candidates

Introduction

If you buy a company you will pay the owners the present value of all the future profits that they expect from the business. You must assume that the current owners understand the profits their business will generate and that if you offer them any less they will not sell. Occasionally buyers do get an amazing deal but the vast majority do not. Frequently acquirers get their sums wrong and offer more than the present owners think the business is worth! It follows that before you buy, you must know how you can do more with the business than the present owners think they can.

In 1996, IBM bought Tivoli Systems for $743 million. At the time Tivoli had sales of slightly less than $50 million. Many commentators concluded that IBM overpaid. Within a year, IBM was able to report Tivoli’s revenue at almost a billion dollars. Tivoli had more value to IBM than Tivoli had to itself.

As shown in Table 2.1 there are really only five good strategic reasons underpinning an acquisition.

TABLE 2.1 Sound strategic reasons for an acquisition

| Reason | Strategic objectives |

| To rationalise capacity in an industry | To increase prices and lower costs by eliminating industry capacity, and gain market power through increased share, lower costs and greater scale efficiencies |

| To consolidate a fragmented market | To gain a cost advantage through creating economies of scale in localised operations |

| To gain access to new products or markets | To sell: • New products to existing customers • Existing products to new customers |

| As a substitute for R&D | To pick technology winners at an early stage of their market development and use superior resources to build a market position quickly |

| To create a new industry | To use a mix of existing and acquired resources, establish the means of competing in a new industry or continue to compete in an industry whose boundaries are eroding |

But we can go further. Deals driven by extra sales, providing the additional planned sales are realistic, perform better than those driven by cost savings. This means that the key question becomes, ‘What can this acquisition add to our existing business?’ This means having a clear idea of how an acquisition can help you do what you do now even better in the future. Acquisitions are not about buying growth. They are about generating growth.

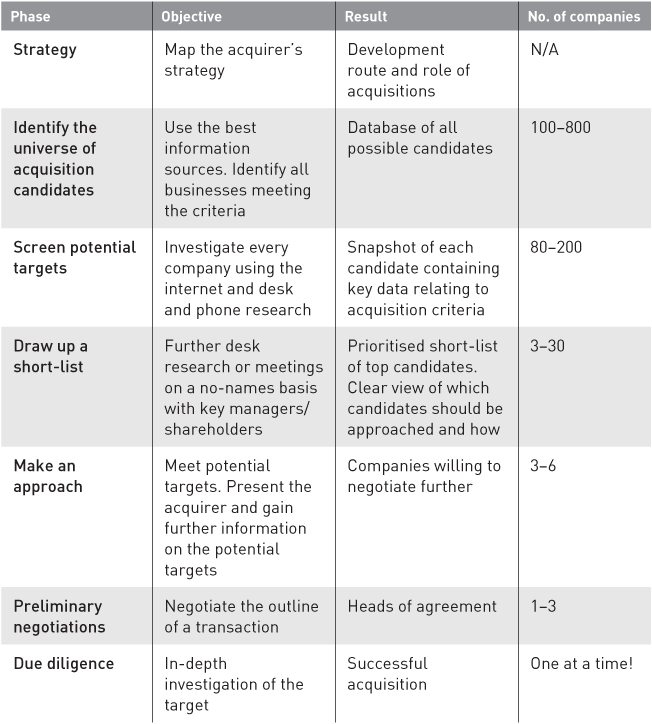

Running an acquisition search

Table 2.2 sets out the typical acquisition search process. Each of the first five stages is covered in more detail below.

TABLE 2.2 Typical acquisition search process

Strategy

The first, essential step is to work out exactly what your strategy is. This means that before you can draw up a list of suitable candidates, you should answer a set of basic questions about the future of the business and the market in which it competes. These are set out in Table 2.3.

TABLE 2.3 Plotting strategic growth routes

| Action | Strategic objectives | |||

| Segment the market | Before we can even start to think about the company’s future we must have a clear idea of the market it serves or wishes to move into. Nothing makes sense without first defining the boundaries of the market by strategically segmenting it into distinct sub-groups of homogenous buyers | |||

| Understand competitive strengths and weaknesses | In existing markets, how well do we: | |||

| • | Deliver what the different customer groups want? | |||

| • | Perform against our main competitors in delivering what these customer groups want? | |||

| • | Play to our strengths while negating any weaknesses that are meaningful to the customer? | |||

| • | Anticipate market change? | |||

| Plot the appropriate strategic growth route (or routes) | Existing markets | |||

| • | Can we enhance our current proposition to better serve customers’ needs? | |||

| – | How are customer demands evolving? | |||

| – | Are there missing skills, products or weaknesses that need to be addressed? | |||

| • | Is there scope for additional market penetration? | |||

| – | Are we strong in the growth segments of the market? If not, what is needed to win business here? | |||

| – | What is our position in other attractive market segments? Where our position is currently weak, is it worth building capabilities say by adding new skills and/or products and services? If so, are they best developed organically or through acquisition? | |||

| New markets/new products | ||||

| • | Is there scope for winning business in new markets? | |||

| – | Are our competitive strengths transferable to new markets? | |||

| – | What is the potentially available prize? | |||

| – | If worth going for, are competitive strengths best transferred through organic development or through acquisition? | |||

| • | Is there scope for developing new products? | |||

| – | What related products or services do existing customers use/value, which we do not offer? | |||

| – | How are/will the needs of buyers change over time? Are our competitive strengths transferable to new products? | |||

| – | What is the potentially available prize? | |||

| – | If worth going for, are new products best acquired organically or through acquisition? | |||

| – | Are there weaknesses that need to be plugged? | |||

| – | Do we need additional capabilities and resources? | |||

| The competition | • | How is the competition developing? | ||

Having taken the strategic view of the various development routes, it should be possible to rank them and define a growth strategy with prioritised opportunities and preferred method of growth (organic, M&A, joint venture/partnership). From here we can state M&A objectives, develop criteria for identifying the most promising candidates and create a pipeline of priority acquisition targets.

Acquisition criteria

Acquisition criteria need not be complicated; in fact the more precise they are the better. Think of the process as being akin to buying a house. If you tell an estate agent you want to buy 15 Acacia Avenue he or she knows exactly what to do next. If you say you want a three-bedroom semi somewhere in the south east of England the agents will come back with such a long list of potential properties you will not know where to start. One acquisition search for facilities management companies yielded 800 names and got nowhere whereas an engineering company that worked out where it could add value to an acquisition specified a tight list of criteria which led to a short-list of three candidates and then to a deal.

Acquisition criteria comprise a mix of ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ issues. ‘Hard’ issues are quantifiable, such as revenues or employee numbers; ‘soft’ issues include skills or culture. It is often powerful to specifically exclude aspects of a target, or elements of its business model, which are unsuitable. For example, no unprofitable businesses, or no contract publishers, or no companies with more than 10 per cent sales to the automotive industry.

Table 2.4 sets out some example acquisition criteria, split between hard and soft issues.

TABLE 2.4 Example acquisition criteria

| Acquisition criteria should relate to strategy; they should be simple and look further than financials | |||

| Hard/financial | Soft/operational | ||

| Size | Skills | ||

| – Turnover, employees | – Products/services, people, accreditations | ||

| Business area | Customers | ||

| – Products, services | – Key customers, industry segments | ||

| Geography | Operations | ||

| – Location, markets served | – Actual activities, sales splits | ||

| Facilities | Sources of incremental value | ||

| – Locations | – Contracts, skills, relationships | ||

| Published information | Unpublished information | ||

Identify the universe of acquisition candidates

The first step in identifying potential acquisition targets is to map the market. The following case study gives an example of how this might be done.

CASE STUDY 2.1 E-cooking

A nationally renowned cookery school has been approached by a supermarket group to provide digital cookery courses for its customers. At the same time, the owners have been talking to the local further education (FE) college about providing a series of non- European modules. They figured that with the right platform these modules could be sold to FE colleges nationwide as they are all subject to the same funding constraints as the local college.

While the school has access to a large number of experienced chefs of all nationalities and is very good at classroom education, product sourcing, menu planning and recipe development, it does not have the time or expertise to develop the digital side and has decided to explore the possibility of acquiring the ‘missing link’ – digital expertise.

Initial analysis of the UK e-learning market shows three distinct segments, each served by different players (see Table 2.5).

Market mapping is an important first step in identifying targets. It is surprising how often even experienced acquirers do not understand what their proposed acquisitions actually do and how they make money.

As digital content would provide the means of supporting online course delivery, this is the logical segment to explore. Bespoke providers have their own products and sell mainly to businesses; therefore the most appropriate targets will be found amongst the off-the-shelf providers. With this established, the off-the-shelf players are then screened based on strategic fit, market position and quality of the underlying business.

Screen potential targets

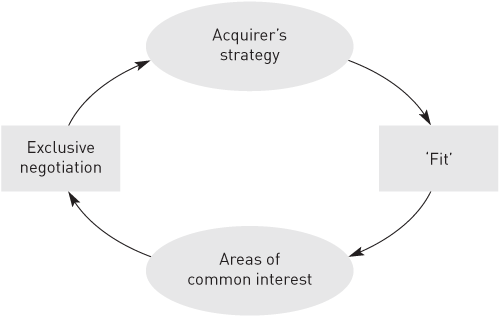

Serious acquirers build a database of targets as a part of their acquisition screening and monitoring process. This approach is particularly appropriate in fragmented markets or less well-known territories. It is also a good way of finding and approaching a business when it is not officially for sale, doing a ‘sweetheart deal’ and thereby avoiding an auction, as shown in Figure 2.1.

A systematic approach, designed to search out the most appropriate opportunities, can go a long way to preventing the disappointment of finding that a suitable acquisition was missed. This information can also form the starting point for the evaluation process once negotiations start with a target.

Some acquirers even use their database as a negotiating tool, by leaving the target company’s owners in little doubt that the acquirer has a number of choices and is, therefore, unlikely to overpay. Exasperated by the antics of its US counterpart, one chairman of a UK plc thumped a thick acquisition search report on the table and shouted, ‘I have a lot more companies to go and negotiate with if we don’t get this deal sorted out soon.’ The transaction completed in a matter of days.

The objectives of a systematic search are to find out:

- What companies are in the market/market segment(s) of interest

- How close their fit is to the acquirer’s acquisition criteria

- Who owns them (independent shareholders, managers, parent companies)

- Whether they are available.

An advantage of a search is that it allows you to select acquisition targets based on their quality of fit, as opposed to availability. In other words, it assesses the whole range of businesses with a good fit to the acquisition strategy and acquisition criteria. With a coherent basic knowledge of each target and its competitors, the prospective acquirer has at least the basis for making a decision, determining which ones to approach and possibly proceeding into initial discussions. Of course you will need a lot more detail on the target if you decide to go on and make an offer for the business.

The effort required to research a market for a list of acquisition candidates will depend greatly on the characteristics of the desired acquisition. For instance, if the search is limited to a narrow market or businesses with a large turnover in a single country then the numbers involved will be limited.

The researchers building the database can call on the plethora of available information sources. These include:

- Financial and company databases

- Search engines, leading to company websites and most of the sources below

- Trade associations

- Industry publications and directories (now largely electronic)

- Trade show directories/catalogues (now mainly available electronically)

- Buyer’s guides

- Financial surveys

- Published market reports (e.g. Frost and Sullivan)

- In-house knowledge

- Suppliers and customers of the industry.

If no acquisition results from a search it means that no appropriate company is currently available. The sector can then be monitored for developments and in the meantime resources can be more usefully directed elsewhere. For example, the European industrial ceramics business went through a period of consolidation as many companies were acquired, leaving a handful of significant companies in independent ownership. Prospective acquirers, having established contact with each of the remaining companies, could take no further action in the sector and had to concentrate development resources elsewhere.

Should an opportunity to acquire arise at a later stage within the screened sector the acquirer will have an understanding of all the potential targets and will be able rapidly to compare the available company with its competitors.

Using outside help

The acquirer’s staff may have sufficient resources, industry knowledge and contacts for this process to be conducted in-house. If this is not the case, it may make sense to use external organisations to help articulate the strategy, perform a structured search or help understand target companies. The occasions when this makes the most sense are when:

- Targets are sought in a fragmented or opaque market.

- Targets are sought in unknown territories.

- The acquirer requires insight into a seemingly attractive target about which it has insufficient knowledge.

Draw up a short-list

Having defined what it is looking for, an acquirer must now identify the targets that are worthy of further consideration. This means ranking the long-list of potential candidates. Doing this involves collecting enough information to make informed decisions. The process is illustrated in Figure 2.2.

Consultants have an advantage as they can seek and obtain information using professional interviewing skills from managers who might otherwise be reluctant to speak to an acquirer directly. The use of face-to-face interviews alongside telephone interviews and desk research gives the best available results. Consultants can also approach shareholders so as to understand their intentions on a ‘no-names’ basis. In addition, search consultants are often prepared to take a significant proportion of their fees on success, although they will invariably require a fixed-fee element for their work. Those who accept the highest proportion of a contingent fee will be more deal-driven and perhaps less discerning; those preferring to avoid high contingent fees tend to be more strategic. The selection of consultants will revolve around trust and a view of their ability to perform. It is worth ensuring that they will use original industry research and that the project will not be entirely staffed by juniors.

Other ways of finding candidates

Apart from building a database of targets through research, acquirers can attract or identify opportunities in a number of other ways. These are:

FIGURE 2.2 Shortlisting acquisition targets based on market position, growth and strategic fit

- Exploiting contacts and knowledge within the business

- Communicating an acquisition profile to introducers

- Advertising

- Waiting to be approached by potential sellers.

No single one of these methods is the best. They can all work, which is why successful acquirers use a combination of them.

Exploiting contacts and knowledge within the business

Should the prospective acquirer’s strategy call for an acquisition of a close competitor, a supplier or even a customer, there will already be a great deal of knowledge to tap within the acquirer’s own business. Operational management should be aware of the players within their sector and they may already know the management and some of the shareholders. They should also be very well placed to provide insights into their strengths, weaknesses and potential fit with the acquirer. All this makes it very straightforward for the acquirer’s operational managers to develop a profile of some prospective targets.

However, you should also remember that this resource has inbuilt bias. Line managers see the weaknesses in rivals and they can hold strong views born of the scars of battle. Their knowledge may also be out-of-date, particularly of more distant businesses which they come across rarely. Finally, their opinions will be more operational than strategic – there is nothing which excites a sales director more than buying out the competition.

A word of caution: make sure that in the excitement of the chase, line managers do not run around making unauthorised approaches or offers. Unless they are well trained, there is every chance of them drawing a blank, or getting into an embarrassing mess. One CEO of a major engineering group recently found himself backpedalling furiously after a line manager unwittingly offered 20 times current profits to a business that had not even been properly screened as a target.

The M&A teams in acquisitive groups are usually good at finding ways to meet the shareholders of businesses they are interested in. They are able to explore avenues of potential cooperation. A major benefit of using internal knowledge is that, where relationships exist at the right level, it may be relatively easy to find the environment in which to open discussions with the owners. The ideal is then to form a relationship with the business and its owners. This will be on both a business and a personal level. If the personal relationship works it is all the easier to sell the benefits of fit between the businesses. Of course, if the strategy is right and the target is right, both sides should see the benefits. At the very least, an introductory meeting can be used to leave a marker, making it clear that you would be interested in a discussion should the shareholders decide to sell. Should the business be put up for sale, the shareholders will inform their corporate finance advisers of any such approaches and these will undoubtedly be followed up.

Communicating an acquisition profile to introducers

Acquirers who want to ensure that they see as many relevant deals as possible stay in touch with the ‘introducers’. These introducers include investment banks; the large, medium and, sometimes, small accounting firms, with corporate finance activities, as well as corporate finance boutiques; wealth managers; and individual brokers or consultants. Introducers increasingly tend to be sector specialists as opposed to generalists working on a wide range of deals.

You need to keep in touch with the introducers in whom you have confidence. Keeping them up to date with your acquisition criteria keeps your name in front of them and helps you get onto their call lists when they are looking for buyers. Good intermediaries prefer to be selective in who they invite to look at a business.

Staying in touch also has the advantage of sparking possible ideas for the acquisition of a business that is not officially for sale. For example, when discussing an acquisition brief and the reasons for fit, an introducer may be able to make a suggestion based on knowledge of the sector and of the intentions of the companies he or she deals with. Introducers can then start the process of brokering a deal, starting on a ‘no-names’ basis if need be.

Prospective acquirers should make sure they look like a good option when presenting themselves to introducers. Personal relationships can count for a lot, but introducers will also be asking other questions. Most of them will work on a contingent basis (i.e. they only get paid when a deal completes) which means that their main concerns will revolve around your ability to complete a transaction. They will ask themselves questions such as:

- Is the acquirer realistic about financing acquisitions?

- Does this acquirer have a serious strategy?

- Will it make a realistic offer for a target business?

- Has it got board approval to acquire?

- Has it got the procedures and resources to complete the transaction?

- Will it be prepared to pay my introduction fee (should there be one)?

Auctions

The downside of dealing with introducers is that you can end up on the long-list of companies that are invited into a controlled auction. This means being given a glossy but rather vague information memorandum and being asked to name a price to get through a first round. Then, access to management, the company’s facilities and to further information ranges from non-existent, through stage-managed, to reasonable.

These auctions are a necessary evil and not for the faint-hearted. By definition the successful bidder will have overpaid. You should only enter an auction if you have the inside track and that means having done a lot of homework to establish that you really can add value as the new owner of the business.

Advertising

Apart from smaller deals in certain sectors, advertising is not a particularly effective way of finding opportunities. The exception is in those industries, such as retail and hotels, where businesses are regularly advertised for sale in the trade press. Acquirers can scour these advertisements and bid for those of interest. Outside the specific trade press in these industries, an acquirer will typically find searching advertisements a frustrating experience. They encounter the frustration that some of the sellers who advertise are not entirely serious about the sale of the business, or are not particularly well-organised. Businesses for sale that are not advised by a corporate finance house tend to be the least serious.

Only the most undiscerning and opportunistic acquirers should advertise for candidates to acquire. They will find that the enquiries they attract are not particularly serious or attractive.

Waiting to be approached by sellers

Alternatively companies can wait to be approached by sellers. Whilst this may work reasonably well for well-known companies, or companies with a track record of acquisitions in the sector, even experienced acquirers do not rely entirely on opportunities coming to them. Less-well-known buyers will have to be very patient if all they do is sit and wait for the ideal opportunity to come along.

Make an approach

Having prioritised the short-list and made an investment case for each candidate on it, it is now time to initiate contact. Think carefully about who to approach, as there may be a range of shareholders with different levels of influence. A classic mistake made by inexperienced acquirers is to approach the managing director, who may have no interest whatsoever in seeing the business sold, fearing that his or her job may be at risk.

A prospective buyer will have to reveal itself sooner or later. It is not compulsory for the buyer to make the approach itself, but it certainly helps. For an approach to look serious, it should be well thought out and clearly come from a credible buyer. If the approach must be made via an intermediary, the chances of an initial meeting are increased if the client’s identity is revealed or if there is a promise that it will be revealed at the meeting.

If the acquisition candidate is in the same market, there may already be some personal contact at board level, or there may be a common acquaintance who can make the introductions in person. Otherwise, the initial approach is normally by way of a formal letter to the major shareholder stating that:

- You are interested in making an acquisition.

- The company looks interesting on the basis of public information.

- You have funds available and board approval.

- If this is of interest, you would appreciate an initial discussion.

If the letter does not receive a reply, it must be followed up with a telephone call. Any decent company will receive unsolicited offers from prospective purchasers on a regular basis and it is not unknown for intermediaries, without any mandate from prospective purchasers, to spray the market with letters hoping to get some expressions of interest on which to build a transaction and thus earn a fee. In addition, approaching a business during its busiest period of the year may mean that the approach gets filed in the bin. So do follow up any approaches if you receive no reply – but make sure that you do not cross the line and be regarded as pestering them. This can be an extremely fine line.

Acquiring a company is much like acquiring a customer. Just as you would not expect to make a sale following a single letter and follow-up call, nor should you expect to find a ready and willing acquisition candidate after a single letter and follow-up call. The primary objective of that first meeting is to start building a relationship. Nothing will happen until there is mutual trust, rapport and respect and this will not come overnight. First impressions are crucial and the way you make your first approach will probably determine whether a fruitful dialogue ensues or you are rebuffed, so prepare thoroughly. Approaches are more likely to be well received if the strategic thinking behind the potential acquisition is explained in a businesslike but tactful way, focusing on synergies and benefits such as operational fit and cultural similarities. You should also evaluate the backgrounds and incentives of different shareholders so you can work out who is likely to be most receptive to your approach and why.

Even if an expression of interest comes from a well-respected potential acquirer where the strategic fit is good, a prospective seller will ask itself the following questions before going any further:

- Is the sale of the business a sensible exit route?

- Is the sale of the business the preferred exit route?

- If so, does it make sense to sell the business now?

- Does it make sense to sell to this buyer?

- Are there likely to be other serious buyers?

For this reason, it may take several weeks, or months, for the exploratory stage to get going. When it does, the buyer’s objectives are to:

- Gather information on the business to confirm its attractiveness

- Persuade the owners to sell

- Agree on how to take the acquisition forward to the next stage (preliminary negotiations).

If the exploratory stage does not take off, keep in touch (see case study 2.2). Everyone sells eventually. The objective is to be called first when the target does become available.

CASE STUDY 2.2 Keeping in touch

A leading British manufacturer of engineering steels had spotted that its customers were increasingly turning to stockholders to provide basic, early-stage, manufacturing operations on a just-in-time basis. While this was a source of extra added value, it was also changing the balance of power in the high-value end of the market as buying power became increasingly concentrated amongst five capable stockholders.

The manufacturer decided to acquire one of these stockholders. A market review suggested that only one would in fact be a suitable candidate. It was part of a small, publicly quoted industrial conglomerate. An approach was made to the chairman, which was immediately rebuffed. However, contact was maintained at various levels and when, six months later, the conglomerate decided to sell to a French company that was interested in another part of the group, the stockholder became available.

Alternatively, if the two businesses have a strong and coherent fit the idea of working together can start to take shape. This approach is often difficult for competitors to put into practice, but it could be achieved, for example, through a joint venture to enter a new market or territory together. Alternatively, it could be a joint supply arrangement to obtain better rates from suppliers, or an industry benchmarking club. Obviously this route has significant advantages as the two businesses become natural partners. In addition, the management teams get to know each other and it becomes clear as to how well they could work together. The evaluation will in fact have begun.

Case study 2.3 is a good example of this approach in practice.

CASE STUDY 2.3 Joint initiative and joint venture as stepping stones to acquisition

Reed Exhibitions, the world’s leading trade show organiser, has grown successfully through a sustained acquisition programme. It identified Brazil as a major country in which it needed a presence, but found that it faced stiff competition from major German and other competitors who had already built relationships, and in particular laid down clear markers, with the leading local organiser, Alcantara Machado. Reed saw that Alcantara’s building products trade show was struggling, so suggested that it should enter into a local joint venture with Reed’s blockbuster event in Europe. Reed put a lot of effort into this initiative, which went very well.

Soon after this success, a family dispute within Alcantara risked dividing the company into factions. Reed was perfectly positioned with insider knowledge to suggest that it should buy out the troublesome party and take what amounted to a controlling stake in the business. Reed then developed the business further and exercised its option to take full control five years later. Through these steps it had catapulted itself to market leader in a key economy with a business worth over £100 million.

Case study 2.4 is an example of an acquisition search conducted by a search consultancy on behalf of a group, which had taken the strategic decision to increase its share of the liquid waste business. Due to the impending consolidation of the UK industry, time was of the essence and targets were sought in a highly fragmented market.

CASE STUDY 2.4 UK waste management acquisition search

Acquirer

Water utility, with a limited operation in liquid waste transport, treatment and disposal

Objective

- Review market structure, growth prospects, entry barriers and opportunities in each selected geographic region.

- Identify acquisition targets.

Parameters

Targets were sought which fell within the following parameters:

- Involved in the transport of liquid industrial waste

- Involved in the treatment of liquid industrial waste

- Profitable, or at least breaking even

- Preferably owner-managed

- Ownership of, or guaranteed access to, licensed disposal sites

- Minimum size: five owned tankers

- Manufacturing customer base preferred

- Industrial cleaning excluded.

Method

- All relevant companies were identified using industrial and local directories, contact with major customers and regulators.

- A database of 400 potential targets was developed.

- Each of the potential targets was contacted to ascertain whether it matched the acquisition parameters.

- Those companies which failed to meet basic size, capability and service criteria were eliminated.

- A first short-list was reviewed with the acquirer, and targets were prioritised. The top 15 companies were selected.

- Face-to-face interviews were arranged with the shareholders and senior management (they were often the same) of the 15 companies with the best fit. These meetings resulted in detailed profiles on each one as an acquisition target. Information already obtained was confirmed and significant further detail was added about each operation. The market position of each company was confirmed and the aspirations of shareholders, including their willingness to join forces with a major company, were investigated. The acquirer’s anonymity was retained during this phase.

- The results were reviewed by the acquirer. Three companies were rejected as unsuitable acquisition targets. (One of them was treating five times more waste than the capacity of its facility, which was situated over a disused mineshaft!)

- Introductions were made to the owners of 12 of the targeted companies. The manner of each introduction was tailored to the shareholder’s circumstances and aspirations.

Result

On the basis of the information obtained and the relationships created with the 12 companies introduced to the acquiring group, eight targets chose to enter into discussions, and two were acquired. This result was achieved in a competitive market with a number of other players simultaneously seeking to consolidate the sector.

The water company continued to grow the business through organic means. Meanwhile, the database of potential targets allowed new opportunities to be evaluated as they arose over the following years and industry consolidation continued.

Conclusion

Experienced acquirers often comment that finding the company to acquire is the easy part of the exercise. The secret is to start with a well-worked-out business development strategy where acquisitions are seen as one tool in the company’s growth strategy where the primary purpose is not to help the company grow big quickly, but to help it do whatever it does, better. This will help in drawing up a focused list of acquisition criteria which can be used to look for and screen potential targets, leading to a pipeline of priority acquisition targets and developing relationships with high-priority targets.