Chapter 6. Color Keying

–Franz Mairinger (Austrian Equestrian)

Color keying was first devised in the 1950s as a clever means to combine live-action foreground footage and backgrounds that could come from virtually anywhere. As of 2007, the tools to do this are more powerful than ever, but the overall process still remains full of pitfalls—pitfalls that won’t likely be overcome until some other means evolves to define precise areas of transparency in foreground footage (and several contenders are in some form of development).

For those reading nonlinearly, this chapter extends logically from fundamental concepts about mattes and selections in Chapter 3, “Selections: The Key to Compositing.”

The process goes by many names: color keying, blue screening, green screening, pulling a matte, color differencing, and even chroma keying, a term that really belongs to analog color television, a medium defined by chroma and heavily populated with weather forecasters.

The purpose of this chapter is to help you not only with color keying of blue- and green-screen footage but with all cases in which pixel values (hue, saturation, and/or brightness) stand in for transparency, allowing compositors to effectively separate foreground from background based on color data.

Novices often wonder if a background must be blue or green to be keyed. The answer is no, although specialized tools, such as Keylight, work with only the digital primaries red, green, or blue. It also happens that blue and green are primary colors not dominant in human skin tones, and most foreground elements (costumes and props), while they might be blue or green, tend to be less purely so. That’s the hope, anyhow...

All of these methods extract luminance information that is then applied to the alpha channel of a layer (or layers). The black areas become transparent, the white areas opaque, and the gray areas gradations of semi-opacity; it’s the handling of these gray areas that typically determines the success or failure of a matte.

Good Habits and Best Practices

Before we get into detail about specific keying methods and when to use them, here is some top-level advice to remember when creating any kind of matte:

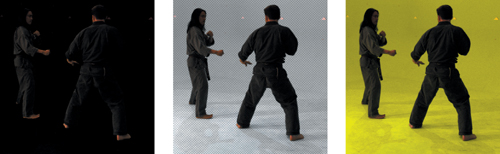

• Use a bright, saturated, contrasting background (Ctrl+Shift+B/Cmd+Shift+B) such as yellow, red, orange, or purple (Figures 6.1a, b, and c). If the foreground is to be added to a dark scene, a dark shade is okay, but in most cases bright colors better reveal matte problems. Solo the foreground over the background you choose (Figure 6.2).

(Source footage courtesy Pixel Corps.)

Figures 6.1a, b, and c. The background influences what you see. Against black, almost no detail is visible (a). Checkerboard reveals shadows (b), but flaws in the matte are clearest with a bright, solid, contrasting background (c).

Figure 6.2. The keyed layer can be soloed at any time, revealing it against the background of your choice.

• Protect edge detail. This is the name of the game (and the focus of much of this chapter); the key to winning is to isolate edges as much as possible and focus just on them so as to avoid crunchy, chewy mattes (Figure 6.3).

Figure 6.3. A coyote ugly, chewy matte (this one exaggerated for effect) is typically the result of clamping the foreground or background (or both) too far.

• Keep it simple, and be willing to start over. Artists spend hours on keys that could more effectively be redone in minutes, simply by beginning in the right place. There are many complex and interdependent steps involved with creating a key; if you start to feel cornered, don’t stay there.

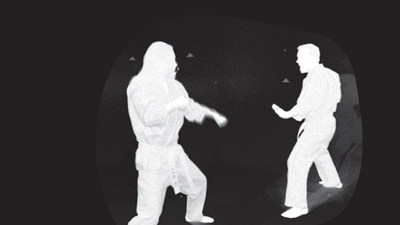

• Constantly scan frames and zoom into detail. When possible, start with a tricky area of a difficult frame; look for motion blur, fine detail, excessive color spill, and so on, and keep checking various areas in various modes (Figure 6.4).

Figure 6.4. A glimpse of the alpha channel can reveal even more problems, such as faint holes in the foreground, which should be solid white. This is the matte from Figure 6.1.

• Break it down into multiple passes. This is the single most important concept overlooked by beginners. In the vast majority of cases, a successful matte incorporates at least two passes: a core matte whose foreground is 100% opaque and a second edge pass.

I encourage you to review this list again once you’ve explored the rest of this chapter.

Linear Keyers and Hi-Con Mattes

There are cases in which edge detail is not a factor because an element does not need to be completely isolated; for example, you might create a holdout area of an image using a high-contrast (hi-con) matte. To specify one area of a clip for adjustment, a linear key will often do the trick.

Linear keyers are relatively simple and define a selection range based on a single channel only, be it red, green or blue, or even just overall luminance. They’re useful in a wide variety of cases outside the scope of blue- and green-screen shots, although the underlying concepts are also operative when working with such high-level tools as Keylight.

Color Key and Luma Key cannot calculate semi-opaque threshold areas of a matte; Edge Thin and Edge Feather controls instead crudely choke, spread, and blur a pure bitmap. There is seriously no reason ever to use them, so it’s unfortunate that they have the more memorable names.

The most useful linear keyers are

• Extract

The keyers to be avoided at all times are

• Luma Key

• Color Key

Extract and Linear Color Key

Extract is useful for luminance (luma) keying, using the black and white points of an image or any of its individual channels. Linear Color Key is a more appropriate tool to isolate a particular color (or color range).

![]() Close-Up: When, Exactly, Is Linear Keying Useful?

Close-Up: When, Exactly, Is Linear Keying Useful?

Keying using a single channel (or the average of multiple channels) is useful to

• Matte an element using its own luminance data, in order to hold out specific portions of the element for enhancement. For example, you duplicate a layer and matte its highlights to bloom them (see Chapter 12, “Light”).

Extract

Extract employs a histogram to help isolate thresholds of black and white; these are then graded with black and white softness settings. You can work with averaged RGB luminance, or access histogram controls for each of the color channels.

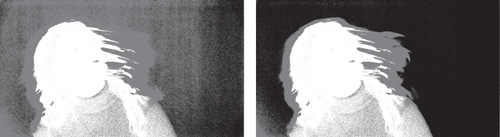

One of the three color channels nearly always has better defined contrast than overall luminance, which is merely an average of the three. Either green or red is typically the brightest and most contrasty channel, while blue generally has lower contrast and higher noise (Figures 6.5a, b, and c).

Figures 6.5a, b, and c. The red channel contains the strongest foreground contrast (a); the green channel (b) shows that the matte contains some green; although it may not be clear at this size, the blue channel (c) is noisier than the other two, typical of digital images and one reason why green screens became popular in the digital era.

Extract is interactive and easy to use, a cousin to Levels. Its histogram shows the likely white or black thresholds on each channel. You bring in the White Point or Black Point (the upper of the small square controls below the histogram), then threshold (soften) that adjustment with the White Softness or Black Softness controls (the lower of the small squares). It is intuitive and relatively easy to use.

![]() Close-Up: All Channels Are Not Created Equal

Close-Up: All Channels Are Not Created Equal

If you set an RGB image as a luma matte, the red, green, and blue channels are averaged together to determine the luminance of the overall image. However, they are not weighted evenly, because that’s not how the eye sees them (Figure 6.6).

Figure 6.6. This grayscale conversion (using Tint) of the channels shown in Figures 6.5a, b, and c weights the three channels according to how the eye sees them. The result appears closest to, but not identical to green.

If you find yourself wanting to use a particular channel as a luma matte, use Shift Channels (Figure 6.7).

Figure 6.7. Shift Channels shifts all channels to red. Alpha is set to Full On as a precaution against transparency data, which should not be used for a luma matte.

Linear Color Key

Linear Color Key offers direct selection of a key color using an eyedropper tool. The default color is blue (ironic given that blue-screen keying is exactly the wrong thing to do with this tool, given the alternatives). The default 10% Matching Softness setting is arbitrary and defines a rather loose range. I often end up with settings closer to 1%.

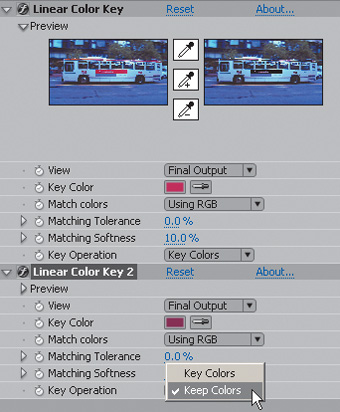

Note that there are, in fact, three eyedropper tools in the Linear Color Key effect. The top one defines Key Color, and the other two add and subtract Matching Tolerance. The eyedroppers work directly on either of the adjacent thumbnail images, as well as in the Layer panel (double-click the layer and choose Linear Color Key in the View pulldown, Figure 6.8). For whatever reason the eyedropper tools don’t work consistently in the Composition viewer.

(Source footage courtesy Pixel Corps.)

Figure 6.8. Linear Color Key can matte a non-primary color range; in this case, the magenta sign on the bus is selected.

You can use RGB, Hue, or Chroma values to match color values. RGB will usually do the trick, but in unusual situations, sample each option before you start fine-tuning. You can adjust Tolerance, which specifies how close the colors have to be to the chosen value to be fully matted, and Softness, which then grades the threshold, softening the edges according to how close the color values are to the target range.

To set up a second instance of Linear Color Key to Keep Colors, you should temporarily turn off the first instance (set to Key Colors) in order to set the color to keep using the eyedropper (Figure 6.9). Alternatively, work in Layer view.

Figure 6.9. Two instances of Linear Color Key: The first is set to Key Colors, the second set to Keep Colors.

The default setting for the Key Operation is to Key Colors, which is straightforward enough. You might guess, therefore, that the other option, Keep Colors, would simply invert the result. In fact, Keep Colors was designed for cases in which the first instance of the effect eliminates something you want to bring back. First instance, you ask? That’s right, you have the opportunity to recover foreground colors despite that they’ve already been keyed out: Add a second copy of Linear Color Key targeting a second range, set to Keep Colors.

Difference Mattes

A difference matte is simple in principle: Frame two shots identically, the first containing the foreground subject, the other without it (commonly called a clean plate). Now, have the computer compare the two images and remove everything that matches identically, leaving only the foreground subject. Great idea.

In practice, of course, there are all sorts of criteria that preclude this from actually working very well, specifically

• Both shots must be locked off or motion stabilized to match, and even then, any offset—even by a fraction of a pixel—can kill a clean key.

• The foreground element may be rarely entirely unique from the background; low luminance areas, in particular, tend to be hard for the Difference Matte effect to discern.

• Grain, slight changes of lighting, and other real-world variables can cause a mismatch to two otherwise identical shots. Raising the Blur Before Difference setting helps correct for this, but only by introducing inaccuracy.

In the interest of full disclosure, I often use track mattes (as detailed in Chapter 3) with a duplicate of the layer, instead of the luminance keys described here, applied directly to the layer. With a track matte, I can use Levels to work with color ranges on all channels, in order to refine transparency. Other artists may consider this approach more cumbersome, preferring to work with a single layer and an effect, so the choice as always is yours.

To try for yourself, begin with a locked-off shot containing foreground action, ideally one in which a character enters the frame (such as the footage used for Figure 6.10, included on your DVD). Duplicate the layer, and lock off an empty frame of the background using Layer > Time > Freeze Frame. Apply Difference Matte to the other layer. Adjust Tolerance and Softness; if the result is noisy, try raising the Blur Before Difference value.

The hand-to-hand green-screen shots in this chapter (such as Figure 6.10) include tracking markers on the background. These are intended to provide dimensional perspective for 3D camera tracking (a.k.a. match moving), which otherwise might not be possible. More on match moving is included at the end of Chapter 8, “Effective Motion Tracking.”

Figures 6.10a, b, and c show the likely result of attempting to key this footage using only Difference Matte. It’s not a terrible way to isolate something when clean edges are not critical, but it cannot compare with more sophisticated methods for removing a solid color background.

Figures 6.10a, b, and c. This effects shot (a) includes a clean plate (b); and the alpha channel of a Difference Matte effect (c) demonstrates that this is not an effective way to key a foreground. Unwanted features such as the tracking markers disappear, however, so this matte could be combined with a regular green-screen key.

Blue and Green Screen Keys

Back in the day, the alternatives to the rather pedestrian Color Difference Key in After Effects were third-party plug-ins, and for a few years there were two choices: Ultimatte for After Effects (now AdvantEdge, Ultimate Corporation) and Primatte Keyer (Red Giant Software, formerly from Pinnacle Systems, and before that, Puffin Designs).

When I label Color Difference Key “pedestrian,” I speak as someone who matted hundreds of shots with it, back before there were alternatives in After Effects. Its methodology is fundamental and can be replicated using basic channel math and Levels controls. It provides the exact methodology that was used for early digital composites, which themselves mimicked optical compositing methods.

Beginning with version 6.0 Professional, an alternative was included free with After Effects: Keylight. Its reputation was already well established prior to its inclusion in After Effects, having even earned it a Technical Achievement Award from the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. The competition has by no means disappeared (I personally remain a big fan of Primatte) but Keylight is part of After Effects, so it’s the main focus of this chapter.

Keylight is useful in many keying situations, not just studio-created blue- or green-screen shots. For example, you can use Keylight for removal of a murky blue sky (Figure 6.11). You wouldn’t use Keylight to pull a luminance key, however, or when simply trying to isolate a certain color range within the shot; its effectiveness decreases the further you get from the three primary colors.

Figure 6.11. In one pass, with no adjustments other than selecting the sky color, Keylight effectively knocks out the background, even preserving motion blur of the bird in flight. The sky is nowhere near a perfect blue: Blue saturation is around 50% and only about double the amount of red.

Keylight is most typically employed to a back-plate shot against a uniform, saturated, primary color background. It is used when preservation of edge detail is of utmost importance—in other words, most typically (but not exclusively) when working with footage that was specifically shot to be keyed against a screen of blue or green.

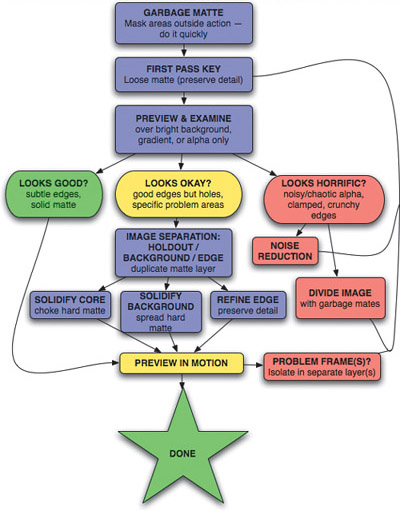

Steps to a Perfect Key

Figure 6.12 shows a process tree that outlines the steps detailed below. No two complex shots are the same, but something like this approach should help you pull a good matte, regardless of the tools used. The next section reprises these steps, specifically using Keylight.

Figure 6.12. This chart summarizes steps that can yield a successful color key. It is also included as a PDF (keyingFlowchart.pdf) on the book’s disc.

The basic steps are

1. Garbage matte any areas of the background that can easily be masked out. “Easily” means no articulated matte (don’t animate individual mask points). As a rule of thumb, limit this to what you can accomplish in about 20 minutes or less (Figure 6.13).

Figure 6.13. The quick-and-dirty garbage matte is your friend for eliminating unwanted parts of the stage.

2. Attempt a first pass quickly, keeping this matte on the loose side (preserving as much edge detail as possible) to be refined later.

3. Preview this at full resolution, in full motion, against a bright primary color. In rare cases, you’re done, but before you throw up your arms in victory, switch to a view that clearly displays the alpha channel. Note any obvious holes in the foreground or areas of the background that have failed to disappear, as well as any noise in the solid areas of the matte (Figure 6.14).

Figure 6.14. A quick diagnosis of Keylight’s first pass at this shot: The shadows must be keyed out because they extend outside the garbage matte area (and right off the set). This in turn has an effect on fine detail such as motion blur and hair, so these areas (hands, hair) may require their own holdout mattes.

If things look noisy and chaotic in the alpha channel or the edges are clamped and chewy, you can

• Start over and try a new pass

• Apply noise reduction to the plate, then start over (see “Noise Suppression” later in this chapter)

• Articulate or track garbage/holdout mattes to isolate problem portions of the footage (see “Typical Keying Challenges”)

4. If necessary, separate the plate for multiple passes. At the very least, it’s often useful to create a solid core and a completely transparent background so that you can focus only on the edge (detailed in the next section), but you may also need to separate individual parts of a layer for a separate keying pass, such as hair or a fast-moving, motion blurred limb.

Just in case I’m not yet succeeding in beating you over the head with it: the most effective way to improve a difficult matte is to break down plate footage into separate passes when keying to prevent problems local to one area from compromising the entire selection.

5. Refine the edge. Zoom in on a challenging area of the foreground edge (200% to 400%), and refine the key to try to accommodate it, using strategies outlined in the following sections. Challenging areas may include

• Fine detail such as hair

• Motion blurred foreground elements

• Cast shadows

You must also watch out for, and consider rotoscoping, foreground features that can threaten an effective key, such as

• Areas of the foreground that reflect the background color

• Edge areas whose color nearly matches the background

• Areas of poor contrast (typically underlit regions of the shot)

A holdout matte isolates an area of an image for separate treatment. You can think of a color key as an edge matte surrounded by two holdout mattes: one for the core, one for the background.

The question then arises as to how these mattes are combined, which is explored in depth in the “Keylight” section.

6. Preview the shot in full motion. Again, note holes and noise that crop up on individual frames, and use the strategies outlined in “Typical Keying Challenges” to overcome these problems. Approaches you may employ at this stage are

• Adding holdout mattes (typically masks), either for the purpose of keying elements individually or rotoscoping them out of the shot (Figure 6.15)

Figure 6.15. It may seem tedious and cumbersome to create individual holdout mattes for things like hair or heavy motion blur, but you could waste hours trying to eliminate the shadows while retaining the detail in one pass; an acceptable roto-matte might take 10 or 20 minutes.

• Holding out the matte edge only, for the purpose of refining or blurring it (see “Matte Problems”)

Ironically, the lazy single-pass approach either leads to a poor result or much more work, overall, as you struggle to make all areas of your shot play nice with one-size-fits-all settings.

You can follow along with the steps using the blueScrn_mcv_HD.mov footage included in this chapter’s Pixel Corps folder on the book’s disc. Completed versions of several of the examples from this chapter are contained in the 06_colorKey.aep project.

Keylight

After Effects CS3 features version 1.2 of Keylight for After Effects; its usage is more or less identical to that of the previous version (the big changes are under the hood, such as support for the Intel Mac).

The first decision in Keylight is most important: sampling a color for the Screen Colour setting (Keylight reveals its UK origins at Framestore CFC with that u). More information to help you make an effective choice lies ahead in “The Inner Workings of Keylight” section.

In the best-case scenario, you create any necessary garbage mattes and then

1. Use the Screen Colour eyedropper to sample a typical background pixel. View defaults to Final Result so you get a matte instantly; set the background to a bright color and solo the plate layer, or examine the alpha channel (Alt+4/Option+4).

2. If in doubt about the Screen Colour setting, turn the effect off and set another instance, repeating as necessary until you have one that eliminates the maximum unwanted background (Figures 6.16a, b, and c); you can then delete the rest.

Figures 6.16a, b, and c. Even with well-shot, high-definition source (a), it is imperative to get the Screen Colour setting right to preserve all of the transparent detail in this shot. Choosing a darker background color (b) creates a more solid initial background, but a lighter color selection (c) preserves far more detail.

(Source footage courtesy Pixel Corps.)

![]() Close-Up: The Eyedropper and the Info Panel

Close-Up: The Eyedropper and the Info Panel

With the Info panel active, sample a pixel in After Effects, either using an eyedropper tool or simply by moving your cursor around a viewer. The Info panel then displays the value that belongs to the exact pixel underneath the selection point of the cursor (the lower-left corner of the eyedropper, the upper-left corner of the pointer).

As in Photoshop, the After Effects eyedropper samples only the color state of a pixel; transparency of any given pixel is always evaluated as if 100%.

Now, as needed, look for areas to refine.

3. Switch View to Status. Opaque pixels display white, transparent pixels black, and those containing transparency are gray (Figure 6.17). It’s an exaggerated version of the alpha channel that shows where your matte is not solid.

Figure 6.17. Sample a background pixel near the center of the image for a good initial key, as seen in the Status matte. The black areas are already completely transparent, the white areas opaque, and the gray pixels constitute the areas of focus; they are the semitransparent regions.

4. Still in Status view, try Screen Balance at settings of 5.0, the default 50.0, and 95.0, and choose whichever one yields the best-looking matte. You might evaluate this based on edge softness or firmness of the foreground matte (Figures 6.18a and b).

Figures 6.18a and b. This initial result, with a Screen Balance of 95 (a), seems in Status view to be inferior to a setting of 5 (b), but a look at the color channel shows the default 95 setting to yield a subtler initial matte edge.

5. If the background is not solid black, you have the option to boost Screen Gain until the gray mostly disappears in Status view. Use this as sparingly as possible, preserving gray at the edges of the foreground. If gray remains in the background, but separate from the foreground such that you can eliminate it with a garbage matte, do so (Figure 6.19).

Figure 6.19. A light touch is best with Screen Gain; some artists (me, much of the time) never raise it above the default value of 100, although settings up to 105 or 110 are often acceptable. Don’t use it to remove anything like the noise in the lower left corner, which is easily solved instead with a garbage matte.

Keylight in general and Despill Bias in particular can enhance the appearance of graniness, particularly of 4:2:2 or other compressed source. If you notice that the keyed foreground appears grainier than the source, reset Despill Bias, and if that doesn’t help, apply the keyed layer as a track matte instead.

6. Now, another optional step (that I often skip): For spill correction, you can set the Despill Bias using its eyedropper. Sample an area of the foreground that has no spill and should remain looking as is (typically a bright and saturated skin tone area).

In the ideal scenario, your matte is now complete. If not (Figure 6.20), this is a decision point to divide the plate. Following are the most basic useful steps for doing so. Before taking these steps, you can revert Screen Gain to 100 to loosen the basic matte.

Figure 6.20. Nice edges—it’s the core of this matte that needs to be a little firmer.

As you may know, the Keylight toolset exists in other compositing applications as well. The Shake implementation of Keylight has the same underlying technology but it has one key addition missing from the After Effects version: inputs for a garbage matte and holdout matte. If you can create these procedurally such that they completely avoid the edge area, this allows you to consider them done and then focus only on the edge, which is all that matters.

I was inspired by what I call the Three Pass Method of shake to devise the following workflow to achieve the same in an After Effects precomp, with as few extra steps as possible. I encourage you to try it out, and let me know if your mattes are improved as a result of focusing exclusively on the edge.

Keylight includes its own controls for adding holdout areas to mattes via the Inside Mask and Outside Mask controls. You draw a mask, set it to None, and then select it under Inside Mask or Outside Mask. This works for garbage mattes, but it’s not a substitute for duplicating the layer to combine multiple keys.

7. Create a precomp containing the Keylight layer with the Move All Attributes option checked. Rename the layer Edge. Duplicate this layer (with Keylight applied), rename it Background, and solo it. For clarity’s sake, turn off effects for Edge for the moment.

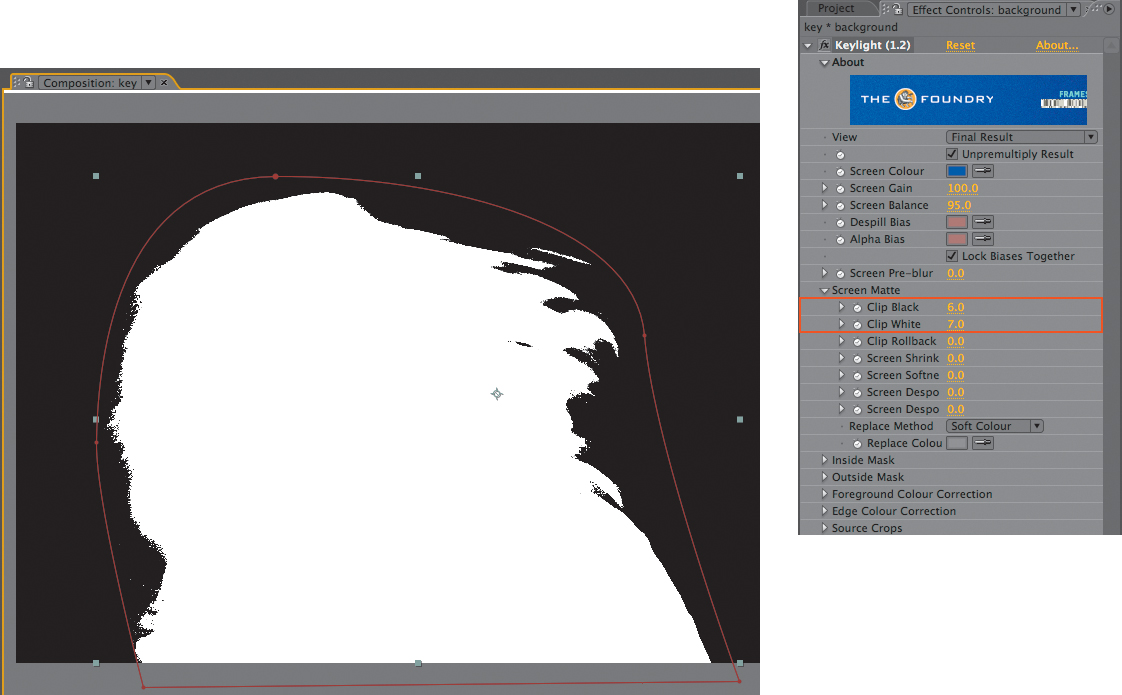

8. Create a background matte that is purely transparent and well separated from the edge, as follows. Mask in any needed overall garbage matte. Raise Clip Black just enough to remove gray pixels from the background in Status view, then lower the Clip White setting just above the same number (Figure 6.21).

Figure 6.21. Screen Gain can always be left at 100 for the edge matte (ideal) if the background is matted separately. A garbage matte eliminates the corner noise.

9. Expand the matte either by raising the Screen Shrink/Grow value or by applying Simple Choker and lowering the Choke Matte setting. Make sure that the selection is completely outside the edge, separated by at least a few pixels; to check this, switch to Final Result view and set the layer’s blending mode to Stencil Alpha (Figure 6.22).

Figure 6.22. Look closely at the edges; the matte from Figure 6.21 has been expanded so that it doesn’t touch them, and the layer is set to Stencil Alpha so that the matte is passed through.

10. Duplicate the original Edge layer again, solo the duplicate, rename it Core and make sure Keylight is enabled. In Status view, lower Clip White until the foreground is completely opaque. Raise Clip Black to a value just below the same number (Figure 6.23).

Figure 6.23. The core matte, like the background matte, is chewy but solid, and is choked so as not to touch the edges.

11. Shrink the matte either by lowering the Screen Shrink/Grow value or by applying another effect such as Simple Choker and raising the Choke Matte setting. Make sure that the selection is completely within the edge, separated by at least a few pixels, then switch to Final Result view and set the layer’s blending mode to Stencil Alpha. The result is a matte of the edge only (Figure 6.24).

Figure 6.24. Thanks to the combination of Stencil Alpha for the background matte and Silhouette Alpha for the foreground, only the crucial part of the matte, the edge, remains. The core can be switched back to Normal blending for the final version.

12. Refine the key of the edge layer, preview each layer in motion to ascertain that they don’t contain errors, and switch the blending mode of the core layer to Normal when you’re done.

This procedure may still leave particular areas needing to be separated with mattes for individual attention—the edge of the hair, for example, might be keyed separately from the body, with an articulated matte (described in detail in the next chapter) to define each.

Get the Best Out of Keylight

So your matte now either looks pretty good or has at least one obvious problem. If you think it’s looking good, focus in on a few details, and note if there are any problems with the following in your full-motion preview:

• Hair detail: Are all of the “wispies” coming through? (Figure 6.25a)

• Motion blur or, in unusual cases with a defocus, lens blur: Do blurred objects appear chunky or noisy, or do they thin out and partially disappear? (Figure 6.25b)

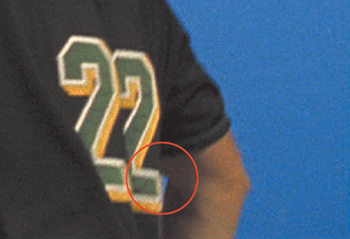

• Screen contamination areas: Do holes remain in the foreground? (Figure 6.25c)

• Shadows: Are they keying as desired (usually all or nothing)? (Figure 6.25d)

Figures 6.25a

Figures 6.25b

Figures 6.25c

Figures 6.25d

Figures 6.25a through d. Fun challenges you may encounter when pulling a color key include wispy hair (a), motion blur (b), contamination of foreground elements by the background color (c), and shadows (d).

You can switch a RAM Preview to Alpha Channel view (Alt+4/Option+4) without losing the cache. Not only that, but the alpha will preview at speed, in full motion.

Alternatively, you may discover something fundamentally wrong with your matte, including

• Ill-defined foreground/background separation or semitransparency throughout the foreground or background

• Crunchy, chewy, or sizzling edges (feel free to invent your own such terms)

• Edge fringing or an overly choked matte

• Errors in the spill suppression

Keylight anticipates these issues, offering specific tools and techniques to address them. Before delving into those (in the “Focusing In” section), here’s how Keylight actually operates.

The Inner Workings of Keylight

A few decisions are absolutely essential in Keylight; most of the rest compensate for the effectiveness of those few. This section offers a glimpse into the inner workings of Keylight, which will greatly aid your intuition when pulling a matte.

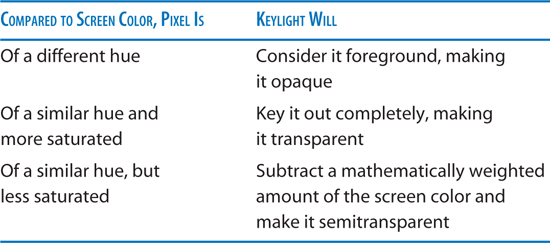

The core of Keylight involves generating the screen matte, and as has been mentioned, the most essential step is the choice of screen color. From that, Keylight makes weighted comparisons between its saturation and hue and that of each pixel, as detailed in Table 6.1.

Table 6.1. How Keylight Makes Its Key Decisions

These top five controls (from Screen Colour to Alpha Bias) differ from those below them in that they work on the color comparison process itself, rather than the resulting matte. You can adjust them without adding any processing load whatsoever, and they work together to yield the ideal matte; the rest of the controls merely correct the result.

The lesson contained in Table 6.1 is that a healthy background color is of a reasonably high saturation level and of a distinct hue.

Those sound like vague criteria, not easily met—and it’s true, they are somewhat vague and often not met. That’s why Keylight adds the Screen Gain, Screen Balance, and Despill and Alpha Bias controls. Screen Gain emphasizes the saturation of the background pixels, and Screen Balance delineates the background hue from the other primary colors. The Bias controls color-correct the foreground.

Screen Gain

One major enemy of a successful color key is muddy, desaturated colors in the background. A clear symptom that the background lacks sufficient intensity is when areas of the background are of a consistent hue, yet fail to key easily. Similarly, a clear symptom that your foreground is contaminated with reflected color from the background is that it appears semi-opaque. In either case, Screen Gain becomes useful.

A Rosco Ultimatte Blue screen contains quite a bit of green—much more than red, unless someone has lit it wrong. Ultimatte Green screens, meanwhile, are nearly pure green (Figure 6.26).

Figure 6.26. The Rosco colors: Ultimatte Blue, Ultimatte Green, and Ultimatte Super Blue. Blue is not pure blue, but double the amount of green, which in turn is double the amount of red. Ultimatte Green is more pure, with only a quarter the amount of red and no blue whatsoever. Lighting can change their hue (as does converting them for print in this book).

Screen Gain boosts or reduces the saturation of each pixel before comparing it to the screen color. This effectively brings more desaturated background pixels into the keying range if raised or, if lowered, knocks back pixels in the foreground containing the background color.

Screen Balance

That takes care of saturation, but what about hue (the actual green-ness or blue-ness of the background and foreground) and how pure is it? Keylight is designed to expect one of the three RGB color values to be far more prevalent than the other two in order to do its basic job. It is even more effective, however, if it knows whether one of the two remaining colors is more prevalent, and if so, which one.

Screen Balance allows you to alert Keylight to this fact.

On this theory, you would employ a balance of 95% with blue screens and leave it at 50% for green screens, and in version 1.1v1 of Keylight, that is exactly how the plug-in sets Screen Balance depending on whether you choose a blue or green Screen Colour setting.

The more generalized recommendation from The Foundry, however, is to set it “near 0, near 100, and compare” these to the default setting of 50 to evaluate which one works best. In other words, imagine there are three settings (instead of 100) and try 5%, 50%, and 95%.

Bias

The Bias settings, Despill Bias and Alpha Bias, color correct the image in the process of keying, by scaling the primary color component up or down (enhancing or reducing its difference from the other two components).

I have found, to my dismay, that keyed footage can become significantly grainier as the result of adjusting Despill Bias. I highly recommend that you compare before and after versions of foreground plate footage if you use this feature, and if the result is adding grainy noise to your footage, reset Despill Bias and try a different despill method (see “Spill Suppression”).

As mentioned, a couple of things have changed with these settings in this new version. They are no longer tied together by default, and The Foundry recommends that in most cases you leave Alpha Bias at the default. They also both now operate via eyedroppers rather than value sliders, and it is recommended that you click the Despill Bias eyedropper on a well-lit skin tone that you wish to preserve; despill pivots around this value.

Focusing In: Clean-Up Tools

Once you are satisfied that you have as good an edge matte as possible, you are ready to zoom in on a detail area and work on solving specific problems.

Increment and save your project after creating a good basic matte, should you wish to revert after further changes.

If you see an area that looks like a candidate for refinement, save (so that you can revert to this as your ultimate undo point), zoom in, and create a region of interest around the area in question.

Now take a look at some common problems you might encounter and the tools built into Keylight that solve them.

Holes and Edges

The double-matte method (core and edge) shortcuts a lot of the tug of war that otherwise exists between a solid foreground and subtle edges. Even with this advantage, both mattes may require adjustments to the Clip White or Clip Black controls.

Remember that with a scroll wheel on your mouse, you can hold down Alt/Option to zoom around the point where you place the cursor.

The game is to keep the largest possible difference (or delta, if you prefer) between these two settings. The closer the two numbers approach one another, the closer you are to a bitmap alpha channel, in which each pixel is pure black or white—a very bad thing indeed (Figure 6.27). The delta between the Clip values represents the area where all of your gray, semitransparent alpha pixels live, so the goal is to offer them as much real estate as possible.

Figure 6.27. Here’s how her hair would look if you hadn’t separated an edge matte for the hair. This is the very definition of a “chewy” matte—you can see individual, contrasty pixels.

If you push the Clip controls too far and need a way out of that corner without starting over, raise the Clip Rollback value. This control restores detail only to the edge, and only what was there in the original matte operation (with those top five controls). Used in moderation, and with a close eye on the result, it can be effective.

Clip Rollback works as follows: Its value is the number of pixels from the edge that are rolled back. The edge pixels reference the original, unclipped screen matte. So if your edges were looking nice and soft on the first pass and removing noise from the matte hardened them, this tool can restore the subtlety.

Noise Suppression

Are your mattes sizzling? Keylight includes a Screen Pre-blur option that you should apply only in a zoomed-in view (to closely examine the result) and only with footage that has a clearly evident noise problem, such as source shot on miniDV. Essentially, this option blurs your source footage before keying it, so it adds inaccuracy and is something of a desperation move. The footage itself does not appear blurred, but the matte does.

A better alternative for a fundamentally sound matte is Screen Softness, found under the Screen Matte controls. Screen Softness blurs the matte itself after the key has been pulled and the matte created, so it has a much better chance of retaining detail. As was shown in Chapter 3, edges in nature are always slightly soft; so used to a modest degree (considering that it is introducing error into your key), this control can enhance the realism of a matte (Figures 6.28a and b).

Figures 6.28a and b. The softer hair matte and the harder matte around the torso don’t line up, and the torso has an unrealistically hard border (a). Adding Screen Softness and a positive Shrink/Grow adjustment can fix this (b).

A more drastic approach, when softening and blurring cannot reach larger chunks in the footage, is using the Despot cleanup tools. Crank these up, and you’ll definitely notice undesirable blobbiness in your matte. For this reason, I don’t trust these controls and usually leave them alone.

![]() Close-Up: Chroma Sampling: The 411 on 4:1:1

Close-Up: Chroma Sampling: The 411 on 4:1:1

Most digital video images aren’t stored as RGB but Y’CrCb, the digital equivalent of YUV. Y’ is the luminance or brightness signal; Cr and Cb are color-difference signals (roughly corresponding to red-cyan and blue-yellow).

Unfortunately, as you might imagine, this type of compression is less than ideal for color keying; hence the recommended approach here for softening the effect of color quantization particularly in common formats such as miniDV.

A better approach, particularly with miniDV and HDV footage (which, by the way, are both guaranteed to add undesirable noise and are typically not recommended for blue-screen and green-screen shoots), is to

1. Convert the footage to YUV using Channel Combiner (the From pull-down). This will make your clip look very strange, because your monitor displays images as RGB. Do not be alarmed (Figure 6.29).

Figure 6.29. This is how an image converted to YUV should look on an RGB monitor—wrong. The round-trip around a Channel Blur appears in the Effect controls (but the second Channel Combiner effect is temporarily disabled, hence the strange look).

2. Apply Channel Blur to the green and blue channels only, at modest amounts (to gauge this, examine each channel as you work—press Alt+2/Option+2 or Alt+3/Option+3 while zoomed in on a noisy area). Make sure Repeat Edge Pixels is checked.

3. Round-trip back from YUV to RGB, using a second instance of Channel Combiner.

4. Apply Keylight, and breathe a sigh of relief.

YUV is the digital version of the broadcast video color space. It is used in component PAL television and is functionally similar to YIQ, the NTSC variant. In After Effects YUV, the red channel displays the luminance value (Y) of the shot, while the green and blue channels display blue and red weighted against green (U and V).

Fringing and Choking

Sometimes, despite all best efforts, your extracted matte contains extra, unwanted edge pixels (fringing), or the keyed subject lacks subtle edge detail because the matte is choked too far.

Keylight does offer the Screen Grow/Shrink control for such situations. On the other hand, if you find yourself having to shrink or expand your matte, it may be a symptom of other problems. Faced with the need to choke or spread a matte (another way of saying shrink or grow), you might first go back and try the initial key again, possibly breaking it down further into more component parts (say, separating the hair) using holdout masks. More information on choking and spreading follows below.

Spill Suppression

Keylight suppresses color spill (foreground pixels contaminated by reflected color from the background) when the matte is initially pulled, as part of the keying operation. Thus spill-kill can be practically automatic if you pull a good initial key.

When is this not what you want? First of all, when it’s an unwanted by-product. There are situations when parts of the foreground that you want to keep are close enough in color range to the background that their color is suppressed. Figure 6.30 shows a scene shot with a green screen out the window in which the interior of the set is also meant to be of a greenish cast, all of which was carefully decided and lit on set.

Figure 6.30. A green-lit set with a green screen out the window: Things like this happen all the time. Applying the matte to the plate with spill suppression limited to areas (such as the top of the monitor) that are reflecting the green screen solves this problem.

Adjustments to the matte can also expose areas of the clip that aren’t spill suppressed. These areas are indicated by the green pixels in the Status view (as in Figure 6.21); spill suppression of these pixels may now be off. In such cases, you specify a Replace Method setting; Soft Colour set to medium gray is a good choice if the only affected pixels are at the edge. It is a cheat, but it may make your key look better by gently desaturating pixels that might otherwise pop.

You can use Keylight for spill suppression only. Follow the same steps as you would to key the footage, but do not adjust any controls below Despill Bias (which you should select using the eyedropper on a representative area of skin tone or equivalent). Change the View setting to Corrected Source; the footage is keyed but the alpha channel remains unaffected.

Finally, spill suppression can lead to other undesirable effects on plate footage. In Figure 6.31, notice how the whole shape of the girl’s face seems to change due to the removal of highlights via spill suppression. Even worse, as mentioned earlier, something about the spill suppression operation in Keylight also seems to enhance the graininess of footage in many cases.

Figure 6.31. Her face doesn’t even look the same without the highlights reflected with the green. Even worse, at this magnification it’s easy to see that the amount of grain noise has increased significantly. It’s a definite case for pulling the matte on one pass and applying spill suppression separately.

Should Keylight’s spill suppression become unwieldy or otherwise useless for any of the above reasons, there is an easy out. Create a nice matte without worrying about spill, precompose the result, and apply it as an alpha matte to the foreground source. Color spill can be removed on a separate pass without adversely affecting the plate footage.

Keylight itself also includes additional spill suppression tools, under the Edge Colour Correction heading (as well as the overall Foreground Colour Correction). Beneath each is a check box to enable it, but nothing changes until you adjust Saturation, Contrast, or Brightness below the check box (or, alternatively, the Colour Suppression and Colour Balancing tools). If necessary, soften or grow the edge to increase the area of influence.

Typical Keying Challenges

As you must know by now, because I’ve seized every opportunity thus far to drill it into your head, the number one solution to most matte problems is to break the image being matted into multiple sections rather than trying to get one matte in one pass. You can divide the matte as follows:

• Core and edge matte (hard and soft matte)

• Holdout masks for particular areas of the frame (useful if lighting varies greatly within the frame, or if one area contains a particularly challenging element, such as hair or motion blur)

• Temporal split (if light conditions change as the shot progresses)

All other tricks fall short if you’re not willing to take the trouble to do this. And now for some more bad news.

On Set

No matter how advanced and well paid you may be, your time is likely to be far cheaper than that of a full crew on set. That means—shocking, I know—you’ll have the opportunity to fix things in post that should have been handled differently on set. You could call it job security (but that sounds so cynical); however you think of it, it’s bound to be part of your job.

If you’re fortunate enough to be supervising the effects shoot (I recommend it for the craft services alone), you can do all sorts of things to ensure that the footage will key successfully later on.

A hard cyclorama, or cyc (pronounced like “psych”), painted a uniform key color is far preferable to a temp cloth background. If you can’t rent a stage that has one, the next best thing might be to invest in a roll of floor covering and paint it, to get the smooth transition from floor to wall, as in Figure 6.32 (assuming the floor is in shot). Regarding the floor, don’t let anyone walk across it in street shoes, which will quickly contaminate it with very visible dust. There are white shoe-cover booties often used specifically to avoid this, but it can be a losing battle.

(Image courtesy Tim Fink Events and Media.)

Figure 6.32. On a set with no hard cyclorama, you can create the effect of one—the curve where the wall meets the floor—using blue-screen cloth instead. It doesn’t behave as well (note the hotspot on the curve), but it will certainly do in a pinch and is much preferable to removing the seam caused by the corner between the wall and floor.

Assuming you begin with a correct-colored, footprint-free background with as few seams and other variations as possible, the most important concerns are to light it correctly, balancing the foreground and background lighting.

The digital age lets shooters play fast and loose with what they consider a keyable background. You may be asked (or try on your own) to pull mattes from a blue sky, from a blue swimming pool, or from other monochrome backgrounds.

How different must the background color be from the foreground? The answer is “not very.” Red is worth avoiding simply because human skin tones contain a lot of it, but a girl in a light blue dress or a soldier in a dress blue uniform often keys just fine from a blue screen (although spill suppression will require special attention).

This job is, of course, best left to a professional, and any kind of recommendations for a physical lighting setup are beyond the scope of this book. But, hey, you’re going to spend more time examining this footage than anyone else, so here are a few things to keep in mind as the on-set effects supervisor:

• Light levels on the foreground and background should match. A spot light meter tells you if they do.

• Diffuse lights are great for the background (often a set of large 1 K, 2 K, or 5 K lights with a silk sock covering them), but fluorescent lights will do in a pinch. With fluorescents you just need more instruments to light the same space. Kino Flo lights are a popular option as well (Figure 6.33).

Figure 6.33. Diffuse white lighting that causes no hotspots in the background is ideal.

• Maintain space between the foreground and background. Ten feet is ideal.

• Avoid dark unwanted shadows like Indiana Jones avoids snakes, but by all means light for shadows if you can get them and the floor is clean. Note that this works only when the final shot also has a flat floor.

• Shoot exteriors outside if possible, using portable backgrounds such as solid color cloths and carpets. You lose the controlled environment of the studio, but the quality of broad daylight can be difficult and expensive to re-create on set. There’s just no key light as big as the sun.

• Record as close to uncompressed as possible. Even many low-end HD cameras allow you to record uncompressed directly to a disk array and avoid the pitfalls of heavily compressed tape formats.

Many computer graphics artists shoot environment reference of a set, either using a camera capable of taking ultra-wide angle photos (using a circular fisheye lens), or by aiming the camera at a reflective silver ball (known in garden shops as a gazing ball). Not only does this provide reference for the lighting setup, but it can be used to re-create HDRI lighting in 3D software.

If the setup permits, bring along a laptop with After Effects on it and with some representation of the scene into which the footage you’re taking is going to be keyed. This can be enormously helpful not only to you but to the gaffer and director of photography, to give them an idea of where to focus their efforts.

Finally, once the lighting has been finalized and before action is called on the shot, ask the camera operator to shoot a few frames of clean plate—the background with no foreground characters or objects to be keyed out later. There are all sorts of ways to make use of this, and it’s easy to forget; if you do, try to get it at the end of the setup, or the end of the day.

Matte Problems

There are specific tools to help you manipulate any matte that needs help. You may simply need to loosen or choke a matte edge.

Minimax is powerful, but not as precise as Matte Choker or Simple Choker. It operates in whole pixel increments to choke and spread pixel values, so the result isn’t necessarily subtle. It provides a quick way to spread or choke pixel data, particularly without alpha channel information (since it can also operate on individual channels of luminance).

A useful third-party alternative to Minimax is Erodilation from ObviousFX (www.obviousfx.com). It can help do heavy choking (eroding) and hole-filling (dilating) in situations where the Simple Choker, well, chokes, and its controls are simple and intuitive (choose Erode or Dilate from the Operation menu and the channel—typically Alpha).

Simple Choker allows you to choke or spread alpha channel data (via a positive or negative number, respectively) at the sub-pixel level (use decimal values). That’s all it does. If you push it hard, it behaves better than the Screen Shrink/Grow control in Keylight, which starts to look blobby. Matte Choker seems more deluxe than Simple Choker (it’s not stuck with that “Simple” label) but it merely adds softness controls that can just complicate a bad key. Don’t be afraid to “settle” for Simple Choker: It’s no monkey wrench.

Edge Selection

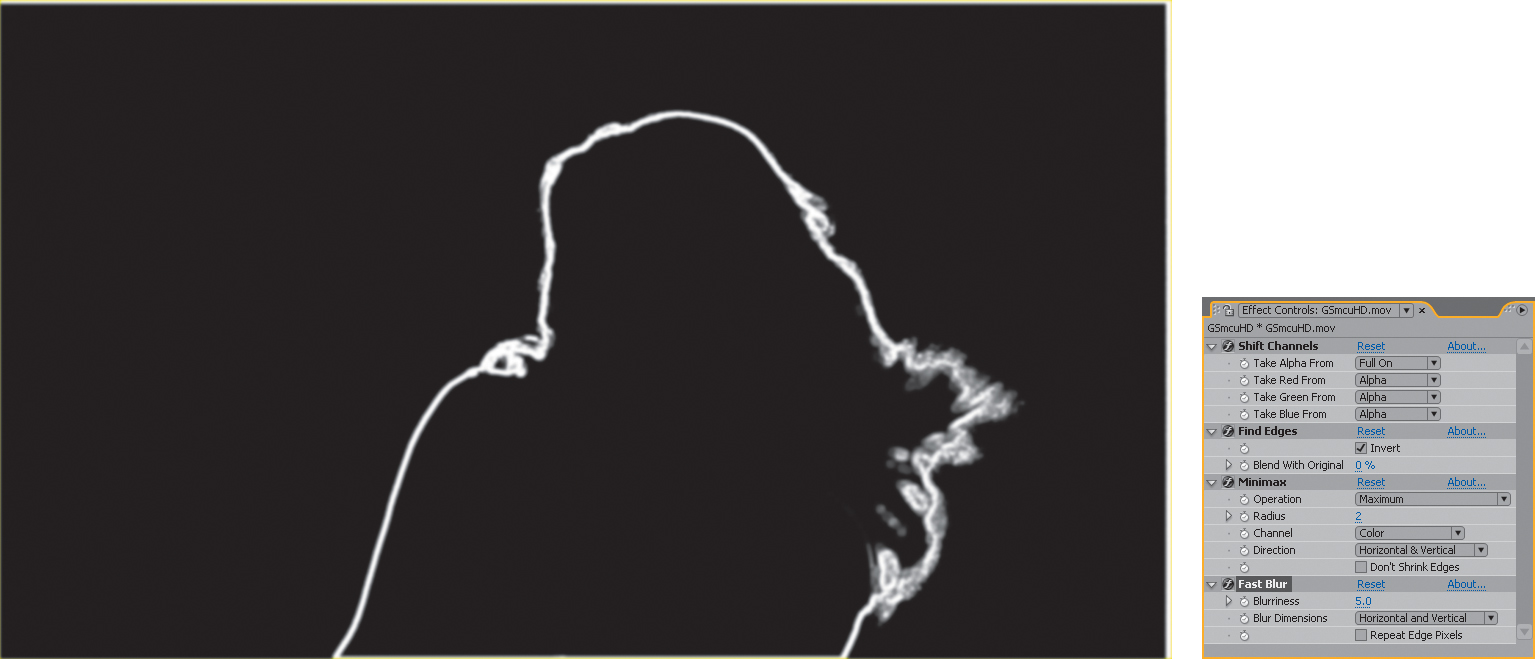

Earlier in this chapter the three-pass method for deriving a matte was introduced; this is one way to derive an edge matte when its specifically the edge pixels you need to select for adjustment. However, the simplest method to get an edge matte is probably as follows:

1. Apply Shift Channels. Set Take Alpha From to Full On and all three color channels to Alpha.

2. Apply Find Edges (often mistaken for a useless psychedelic effect because, as with Photoshop, it appears in the Stylize menu). Check the Invert box (Figure 6.34).

Figure 6.34. You can use this selection to blur the background and foreground together along the edge via an adjustment layer. Beware that the bottom edge is included in the matte; don’t let this bite you if your frame has no padding (non-visible area at the edge of frame).

Minimax is useful to help choke or spread this edge matte. The default setting under Operation in this effect is Maximum, which spreads the white edge pixels by the amount specified in the Radius setting. Minimum chokes the edge in the same manner. If the result appears a little crude, an additional Fast Blur will soften it (Figure 6.35).

Figure 6.35. Need thicker, softer edges? A quick Minimax set to the default Maximum allows you to specify a Radius by which the white area will grow. If the result looks a little chunky, a quick Fast Blur will soften it back.

• Apply the result via a luma matte to an adjustment layer. You should not need to precompose before doing so.

Now what? Fast Blur will soften the blend area between the foreground and background, another way around a chewy matte that doesn’t harm the overall image. A Levels adjustment will darken or brighten the composited edge to better blend it. Hue/Saturation can be used to desaturate the edge, similar to using a gray edge replacement color in Keylight.

Matte Holes

Holes can appear in solid areas of a matte: in the background because of uneven lighting, seams, dirt on the floor, or in the foreground, usually because of reflections from the background (especially the floor). No built-in tool in After Effects deals with these procedurally, but there’s a great third-party tool called Alpha Cleaner, part of the Key Correct set (formerly Miracle Alpha Cleaner in Composite Wizard). Because it is an automated solution, it will occasionally fill holes that should remain unfilled, such as the little triangular gap that can open up under outstretched arms (Figure 6.36).

Figure 6.36. An automated solution, such as Alpha Cleaner (part of the Key Correct Pro pack), fills holes in the foreground matte but may have side effects, closing needed holes such as this tiny gap under the arm.

Thus matte holes present a situation in which you may have to rotoscope. It’s often not as bad as you think it will be; the painstaking part of keying is defining the edge, and holes can often be fixed using crude masks or by tracking in paint strokes (each covered in the next two chapters, respectively).

Matte Fringe

Visible fringing around the edge of a feathered matte can appear when a matte is applied via a track matte. Whether to avoid Keylight’s heavy processing of spill and grain or to build a multilayer matte, you have seen a few reasons to work this way.

One solution to fringing is hidden away in the Channel menu. Remove Color Matting (a difficult name to remember which could instead be “un-premultiply”) is designed specifically to remove background color from premultiplied edges (if the distinction eludes you, review Chapter 3).

Remove Color Matting uses black as the default Background Color (usually the right setting), and this is the only user-adjustable parameter in this effect. You can instead use the eyedropper to sample a background color. If the fringing is bright colored, a white or gray background may have been premultiplied.

The free Unmult plug-in from Red Giant Software is included on this book’s disc. It differs from Remove Color Matting in that it only works with black backgrounds, and it adds actual transparency to pixels based on how much black they contain.

Color Spill

Color spill need not be a big deal. If you’re not happy with the spill suppression in Keylight (or another keyer), you can apply the matte as an alpha track matte to the source footage and pursue alternative options.

Sometimes the Spill Suppressor tool that is included with After Effects will do the trick. It uses a simple channel multiplication formula to pull the background color out of the foreground pixels. All you need to do is select a sample from the background color (you can even copy your original choice of screen color from Keylight, but it mostly matters whether you choose blue or green) and leave the setting at 100%.

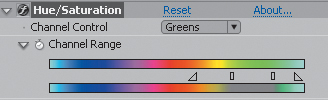

If even Spill Suppressor has undesirable side effects, then it may be advisable to apply Hue/Saturation and target the specific hue that is causing you problems, either desaturating or shifting it. Select the color of the spill under Channel Control—say, Blues (for some reason they’re all plural).

Channel Range contains two color spectrums with a set of controls between them (Figure 6.37). These control the actual range of a given hue. The inner hash marks control the range affected by the controls below; the region between those and the outer, triangular markers is the threshold area.

Figure 6.37. The hash marks and triangles under the upper gradient of the Channel Range control the core and threshold of the affected hue range; the result is reflected in the lower gradient. This is often an effective method to remove spill.

For the best result, turn off Keylight or any other matte operations and work directly with the plate. Set the Saturation for the channel (Blue Saturation or Green Saturation) to –100%. Move the inner and outer hash marks outward until the background is completely gray; the foreground inside the edges should appear unaffected. Re-enable the matte, now without spill.

Conclusion

Keylight is a powerful tool that should offer the results you’re after. Primatte Keyer is also a great option (included as a demo on the book’s disc). Sometimes, however, there’s no way to avoid plain old manual labor. The next chapter offers hands-on advice for situations where procedural keying can’t accomplish everything, and you have to work by hand.