Introduction

AFFLUENZA (n.)—a painful, contagious, socially transmitted condition of overload, debt, anxiety, and waste resulting from the dogged pursuit of more.

In his office, a doctor offers his diagnosis to an attractive, expensively dressed female patient. “There’s nothing physically wrong with you,” he says. His patient is incredulous. “Then why do I feel so awful?” she asks. “So bloated and sluggish. I’ve got a big new house, a brand-new car, a new wardrobe, and I just got a big raise at work. Why am I so miserable, Doctor? Isn’t there some pill you can give me?” The doctor shakes his head. “I’m afraid not,” he replies. “There’s no pill for what’s wrong with you.” “What is it, Doctor?” she asks, alarmed. “Affluenza,” he answers gravely. “It’s the new epidemic. It’s extremely contagious. It can be cured, but not easily.”

Of course, the scene is an imaginary one, but the epidemic is real. A powerful virus has infected American society, threatening our wallets, our friendships, our families, our communities, and our environment. We call the virus affluenza. And because the United States has become the economic model for most of the world, the virus is now loose on every continent.

Affluenza’s costs and consequences are immense, though often concealed. Untreated, the disease can cause permanent discontent. In our view, the affluenza epidemic is rooted in the obsessive, almost religious quest for economic expansion that has become the core principle of what is called the American dream. It’s rooted in the fact that our supreme measure of national progress is that quarterly ring of the cash register we call the gross domestic product. It’s rooted in the idea that every generation will be materially wealthier than its predecessor and that, somehow, each of us can pursue that single-minded end without damaging the countless other things we hold dear.

It doesn’t work that way. The contention of this book is that if we don’t begin to reject our culture’s incessant demands to “buy now,” we will “pay later” in ways we can scarcely imagine. The bill is already coming due. At its most extreme, affluenza threatens to exhaust the earth itself. As the corporate critic Jeremy Rifkin told John some years back, “We human beings have been producing and consuming at a rate that far exceeds the ability of the planet to absorb our pollution or replenish the stock.”

Scientists say we’d need several more planets if everyone on earth were to suddenly adopt the American standard of living.

Welcome to the third edition of Affluenza, fully updated with a different subtitle. Much water has run under the bridge since the first edition was published in 2001, following a period of galloping economic prosperity in America. The book quickly became a hit and has been translated into nine languages while selling nearly 150,000 copies. A second edition was published in 2005, when signs were clear that the prosperity we discussed in the first edition was beginning to falter.

Now eight more years have passed, and during those years the chickens have come home to roost and the hubristic assumptions of 2001 have crumbled. The flaws in the affluenza economic model we described then, coupled with glaringly stupid policy decisions encouraging rampant financial speculation, brought the whole show to a crash in 2008. Since then we have been picking up the pieces all over the world. Personal bankruptcies exceeded 1.5 million the following year, the most ever. Even in 2012, there were 1.4 million such declarations in the United States, about equal to the number of students earning bachelor’s degrees.

In this book, we bring theory and data up to date. There have been many changes since 2001, perhaps equally positive and negative. But the overall impact of the disease called affluenza has not diminished, and the stakes are higher, given the realities of climate change, technological unemployment, and the massive shift toward inequality that began emerging in the United States in the 1980s and exploded after 2001.

AFFLUENZA: THE FILM

Most movies start with a book, but this book started with a movie. John, a coauthor of this book, and Vivia Boe produced a documentary in 1996 about the subject of overconsumption and its many not-so-benign consequences for American society. Their research told them the subject was a huge one, touching our lives as Americans in more ways than any other social or environmental issue. But how to make sense of it? How to present the issue so that viewers could see that multiple problems were caused by our consuming passion and were all connected to one another?

After videotaping more than two-thirds of the program, John and Vivia were still wondering how to weave together the wide range of material they had collected. Then, on a flight from Seattle to Washington, DC, to do still more videotaping, John happened to see the word affluenza used in passing in an article he was reading. It was like that moment in cartoons when the light bulb goes on over someone’s head. That was it: affluenza. A single word that not only made a catchy (pun intended) TV title but also suggested a disease resulting from overconsumption.

Here was a way to make the impacts of overconsuming more clearly understandable—as symptoms of a virus that, in the United States at least, had reached epidemic proportions. They could then look at the history of this disease, trying to understand how and why it spread, what its carriers and hot zones were, and finally, how it could be treated.

From that point on, they began to use the term, asking interviewees if the idea made sense to them. And indeed, physicians told John and Vivia they could see symptoms of affluenza in many of their patients, symptoms often manifesting themselves physically. A psychologist offered his observation that many of his clients “suffer from affluenza, but very few know that that’s what they’re suffering from.”

The documentary, Affluenza, premiered on PBS on September 15, 1997, and was greeted with an outpouring of audience calls and letters from every part of the United States. Clearly, it had touched a deep nerve of concern. Viewers as old as ninety-three wrote to express their fears for their grandchildren, while twenty-year-olds recounted sad tales from the lower depths of credit card debt. A cover story in the Washington Post Sunday magazine about people trying to simplify their lives introduced them as they were watching the program. A teacher in rural North Carolina showed it to her class of sixth graders and said they wanted to talk about it for the next two weeks. On average, the kids thought they had three times as much “stuff” as they needed. One girl said she could no longer close her closet door. “I’ve just got too many things, clothes I never wear,” she explained. “I can’t get rid of them.”

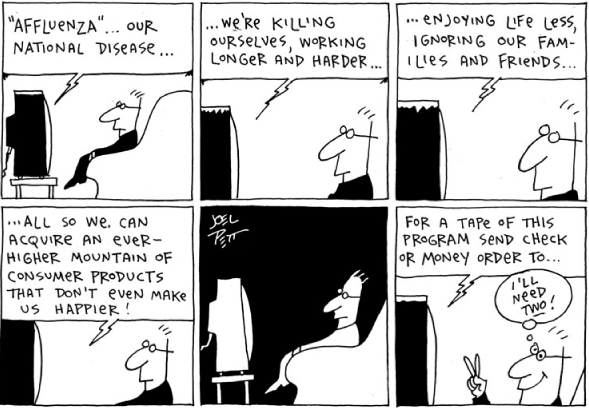

© 2001 by Joel Pett

CROSSING POLITICAL LINES

Though past criticisms of consumerism have come mostly from the liberal side of the political spectrum, Affluenza spoke to Americans of all political persuasions. The head of one statewide conservative family organization wrote saying, “This issue is so important for families.” Ratings and audience response were as high in conservative cities like Salt Lake and Houston as they were in liberal San Francisco or Minneapolis. In colleges, the program was more popular at Brigham Young than at Berkeley. At Appalachian State University in Boone, North Carolina, students and faculty showed it to audiences in both poor mountain communities and upscale churches, recording audience comments and producing a video of their own called Escaping Affluenza in the Mountains.

THE WHOLE WORLD IS WATCHING

We’ve become convinced that this is an issue that troubles people throughout the world. We’ve heard from countries where we couldn’t imagine anyone would be concerned about affluenza—Thailand, Estonia, Russia, Nigeria, for example—but where, indeed, citizens hoped to adopt what was good about the American lifestyle and avoid what was harmful.

An Islamic business magazine in Sri Lanka asked us for a short article about the disease. Activists in rural northern Burma translated the TV program into the local Kachin dialect. A sixteen-year-old Israeli girl sought permission to project it onto the wall of a Tel Aviv shopping center. Seeing overconsumption as a disease, they said, helped them understand it better and explain it to others.

A SOCIAL DISEASE

Often, writers speak of “affluenza” with different emphases. Some have used the term primarily with reference to the spoiled children of the super-rich. Defined as such, it loses the sociopolitical message we put forward and becomes a matter of purely personal behavior. In our view, however, the virus is not confined to the upper classes but has found its way throughout our society. Its symptoms affect the poor as well as the rich, and our two-tiered system (with rich getting richer and poor poorer) punishes the poor twice: they are conditioned to want the good life but given very little possibility of attaining it. Affluenza infects all of us, though in different ways.

AFFLUENZA: THE BOOK

Television, even at its most informative, is a superficial medium; you simply can’t put that much material into an hour. And that’s the reason this book was written: to explain affluenza in more depth, with more examples, more symptoms, more evidence, more thorough exposition. If you’ve seen the video, you’ll recognize a few of the characters and stories.

The first edition arrived on the market just before the terrible tragedy of September 11, 2001. Families and friends suddenly seemed more important than things and work. But then, the consumption propaganda machine kicked into high gear again. If you want to be patriotic, President George W. Bush told Americans, go to the malls and shop. Buy to fight terror.

From Democrats, the message was the same. San Francisco mayor Willie Brown had a million shopping bags printed with big flags on them and bold words: AMERICA: OPEN FOR BUSINESS. Washington senator Patty Murray proposed “Let’s go shopping” legislation that would have removed the sales tax on products during the 2001 holiday shopping season. Almost no one dared to mention that anger and envy over the profligate spending of Americans might encourage sympathy for terrorists in developing countries.

Since the first edition of Affluenza was published, it’s been used widely by book groups and in university classes. We had hoped affluenza would become a household word, and that seems to be happening. An Internet search before our PBS broadcast turned up about two hundred cases of the word on the Web—all of them in Italian, where affluenza simply means affluence. In 2005, a check of the word on Google found 232,000 references to it (!), referring, in the vast majority of cases, to overconsumption. A similar check in 2013 found 2.3 million references, a leap of an order of magnitude. London’s Independent newspaper picked it as one of its most popular new words for the year 2003, and dictionaries are considering including it in the next few years.

Moreover, use of the term continues to grow: a popular play called Affluenza, by James Sherman, has been touring the country for several years. Clive Hamilton wrote a fine book by the same title in Australia in 2007, graciously asking us to borrow the title. Oliver James, a British psychologist, also wrote a good book with the same name in 2009, when there were already one million references to affluenza on the Internet, but unlike Hamilton, James suggested that he had invented the word!

SYMPTOMS

We have divided the book into three sections. The first explores many of the symptoms of affluenza, each—only half whimsically—compared to a real flu symptom. Think of how you feel when you’ve got a bug. You’re likely to be running a temperature. You’re congested. Your body is achy. You may have chills. Your stomach is upset. You’re weak. You might have swollen glands, even a rash.

In the Age of Affluenza, America as a society shows all of these symptoms, metaphorically at least. We present each as a chapter. We start with individual symptoms, then move to the social conditions, and finally turn to the environmental impacts of affluenza.

Some chapters may greet you with the shock of self-recognition—“Honey, that’s me!” You might notice the conditions discussed here taking hold of your friends. You might find some more troubling than others and worry more about your children than about your Mother Earth. You might be well off materially but feel stressed out or empty, as though your life lacks purpose or meaning. Or you might be poor, and angry at your inability to give your children what marketers say they “gotta have” to fit in. Or you have watched bulldozers destroy the only open space left around your community to make room for row upon row of identical tract homes with three-car garages. If you’re elderly, you may have noticed your children’s inability to balance their budget, and you may worry for their children as well.

If you’re young, you may be anxious about your own future.

Wherever you’re coming from, we believe you’ll clearly recognize that at least some of the symptoms of affluenza affect you. Then, as you read on, you’ll begin to see how they’re connected to others less obvious from your vantage point.

GENESIS OF THE DISEASE

In Part Two of this book, we look beneath the symptoms to search for causes. Is affluenza simply human nature, as some would suggest? What was the genesis of this powerful virus? How has it mutated throughout history, and when did it begin to reach epidemic proportions? What choices did we make as a society (between free time and stuff, for example) that deepened our infection? We look carefully at warnings from across time and cultures and at early efforts to eradicate the disease with controls and quarantines.

Then we discover how the spread of the disease has become not only socially acceptable but actively encouraged by all the powerful electronic carriers our technological civilization keeps perfecting. We suggest that affluenza promises to meet our needs—but does so in inefficient and destructive ways. And we contend that an entire industry of pseudo physicians, handsomely rewarded by those with a huge stake in the perpetuation of affluenza, conspire to keep the diagnosis of the disease and the extent of its symptoms from reaching the general public.

CURING AFFLUENZA

But far be it from our intent to leave you permanently depressed. Affluenza can be treated, and millions of ordinary Americans are already taking steps in that direction. A 2004 poll by the Center for a New American Dream (www.newdream.org) found that 49 percent of Americans had claimed to have cut back on their spending.1

The same poll also revealed that 85 percent of Americans think our priorities as a society are out of whack; 93 percent feel Americans are too focused on working and making money; 91 percent believe we buy and consume far more than we need; 81 percent think we’ll need to make major changes in the way we live to protect the environment; and 87 percent feel our current consumer culture makes it harder to instill positive values in our children.

Several cultural indicators seem to show that Americans are building their immunity to affluenza. For example, the number of golfers (an enjoyable sport but a costly one) is down while home gardening is up, and some courses are being converted to parks and other recreational areas. Sales of smaller hybrid cars have jumped in the United States, while SUV sales have fallen somewhat, and total driving in the US leveled out in 2005 and has begun to decline. Reports from cities like Seattle show that many young millennials prefer to rent cars from companies like Zipcar and Car2Go, or to walk, bike, and use public transit. They also seem to be putting off getting driver’s licenses until college age or older.

For the first time in many years, there are more farms rather than fewer, indicating the entry of small, often organic farmers into agriculture and a great new interest among the young in wholesome, unprocessed food. Trends like these are reported in Part Three of the book, along with many natural, technical, and even social remedies for beating affluenza. As with symptoms, we look at treatments, starting with the personal and advancing to the social and political. Our treatments, too, employ the medical metaphor.

We encourage a restored interest in fresh air and the natural world, with its remarkable healing powers. We agree with the futurist Gerald Celente, author of Trends 2000. “There’s this commercial out,” he says, “and it shows this middle-aged man walking through the woods pumping his arms, and all of a sudden in the next cut, there he is on the back porch, woods in the background, walking on this treadmill that must have cost a fortune. It doesn’t make sense. It was so much nicer walking through the woods, and it cost nothing at all.”

We suggest strategies for rebuilding families and communities, and for respecting and restoring the earth and its biological rules. We offer “policy prescriptions,” with the belief that some well-considered legislation can help create a less affluenza-friendly social environment and make it easier for individuals to get well and stay that way.

We also present preventive approaches, including vaccines and vitamins that can strengthen our personal and social immune systems. And we suggest an annual checkup of our vital signs. Ours comes in three phases:

1. You can take a little test to see how you’re doing personally in staying well (see Chapter 17).

2. We find a useful substitute for our current outmoded measure of national health, the gross domestic product (GDP). We recommend an index called the Genuine Progress Indicator (GPI), currently being fine-tuned in several American states. Using multiple indices to discover how we’re doing, the GPI paints a different picture of our success as a society. While GDP has risen steadily throughout our history, the GPI has been falling since 1973 in the United States, and since 1978 globally, because “bads” like pollution are subtracted rather than added to its index.

3. Finally, using the “gross national happiness index”—an idea that comes from the Himalayan kingdom of Bhutan—we can begin to take stock of how satisfied we really are with our lives and what we might do to be more content with less stuff.

CHANGES IN OUR THINKING

We’ve gotten a lot of feedback from readers since we wrote the first edition of this book—hundreds of personal reviews and some excellent journalistic assessments as well. Much of the feedback has been contradictory, so we’ve had to go with what made most sense to us. Criticisms of the book have taken two lines. Our accessible, sometimes flippant, writing style has been praised, and even used to teach writing in college English classes, but other readers have felt it engaging to the point of superficiality—“It feels like a television program” was how some put it. While trying to maintain the book’s light quality, we have also responded to this criticism by taking out some of the silliest stuff, and we have substituted deeper analysis for some of our storytelling. We think this makes this edition a more serious book and hope that it will be seen that way, though we know these changes will not please everyone.

The second major criticism of the first two editions is that we were “too political.” Many readers said that they agreed with our criticisms of consumerism and overspending, but they thought these were personal problems and that we should have stuck to giving people tips to live more frugally and not gotten into dreaded politics. The fact that our historical section includes some ideas from Karl Marx (though it also includes ideas from several prominent conservative economists) waved a red flag for some readers. But we do not apologize for looking to a broad range of ideas. A current Russian joke is illustrative. It goes like this: “Everything Marx said about communism was false. Unfortunately, everything he said about capitalism was true.” If we are to get a handle on affluenza, we must be open to all ideas, not just those deemed “American.”

Moreover, we believe that, if anything, our first editions, and the TV program on which they were based, underestimated the importance of policy while focusing too much on personal behavior. Many of the drivers of affluenza are structural—our economy, as the activist Michael Jacobson put it, is simplicity unfriendly and “structurally opposed to simpler living.” We can see this in the financial crisis, driven in part by personal spending beyond our means but greatly exacerbated by public policies rewarding greed and speculation. So we won’t back down on this one; indeed, this version of the book calls greater attention to the need for better policies.

We want to make clear from the outset that much spending in the United States is driven not by some special American greed, but by reasonable fear and a desire for basic financial security. As we will argue, the insecurity and inequality central to life in the United States are greater drivers of this virus than the gross desire to consume.

LET’S BEGIN A DIALOGUE

This book contains little truly new information, yet the issue in this “information age” isn’t more information. It’s how to make sense of what we already know and how to use values, not just information, as a lever for getting healthy again. We offer a way of understanding seemingly disconnected personal, social, and environmental problems that makes sense to us—as symptoms of a perilous epidemic that threatens our future and that of generations to come. Our intention is to encourage a national dialogue about the American consumer dream so that whatever choices each of us makes about consumption—and the choices we make as a society through policy change—are made with a clearer understanding of their possible consequences.

The underlying message of this book isn’t to stop buying; it’s to buy carefully and consciously with full attention to the real benefits and costs of our purchases, remembering, always, that the best things in life aren’t things.

A NOTE ON NOTES: As we have updated our endnotes from the previous volume, it has become clear to us how quickly numbers change. And in some cases, we offer statistics that are best understood by looking at trends. Occasionally, therefore, we point to sources of multiple data and to more that can be useful to you, rather than simply the source for the number we mention. Moreover, since far more people now get their information online, we have chosen where possible to direct you to supporting material that can be accessed online rather than simply the names of hard-copy articles. We have occasionally cited Wikipedia as a source, knowing that might encourage scolding from some quarters. But the advantage is that Wikipedia pages point readers to many other sources and references, allowing them to dig far deeper into a subject. It is our hope that by opening up more sources for information, we can encourage you to better explore the complex issues surrounding this subject. Finally, where we have not cited the source of quotations, they have all come from personal conversations with the authors.

Happy reading!