1

Commitment and Change

A lot of people are waiting for Martin Luther King or Mahatma Gandhi to come back—but they are gone. We are it. It is up to us. It is up to you.

—MARIAN WRIGHT EDELMAN

A leader sounds a call to summon others. The call is a plea for commitment to a purpose that is defined, embodied, and symbolized by who that leader is and by what he says and does. The commitment that is summoned is often a transformational power, a force that can create substance out of mere dreams and promises through the dedication, involvement, and persistence of those who offer it. The commitment of others is the fulfillment of the leader’s art; without the commitment of others, a leader is just a voice.

Because leaders cannot lead without the commitment of others, understanding commitment in its various forms is central to their purposes. The four forms of commitment are:

1.Political—commitment to something in order to gain something else

2.Intellectual—commitment of the mind to a good idea

3.Emotional—commitment that arises out of strong feelings

4.Spiritual—commitment to a higher purpose

These four forms of commitment combine in various ways to make up a four-tiered hierarchy from the shallowest to the most profound. Political commitment is at the lowest level, intellectual or emotional commitment at the next level, the combination of intellectual and emotional commitment at the next level, and spiritual commitment at the highest level.1 Figure 1-1 shows the four kinds of commitment combining to form four levels, from the shallowest at the bottom to the most profound at the top. The triangle in the figure represents the amount of human energy that becomes available as people make the various kinds of commitments described in the diagram. Given the same number of followers, the least amount of energy is generated when commitment is purely at the political level, more energy becomes available when either intellectual or emotional commitment is inspired, still more when intellectual and emotional commitments are both inspired, and the greatest amount of energy when spiritual commitment is inspired.

Although millions of Web sites and thousands of books offer guidance to leaders, the vast majority of this guidance calls attention to one of the four forms of commitment, but not to all of them. In other words, some guidance explains how to call for political commitment, some how to call for intellectual commitment, some how to call for emotional commitment, and some how to call for spiritual commitment. This book provides a synthesis that will guide any leader to judge the level of commitment needed to produce change in any given situation, to know whether or not it is possible, and what the leader might do in order to gain that form of commitment from followers.

Figure 1-1. Four kinds of commitment at four levels, from the shallowest level at the bottom to the most profound level at the top.

Political Commitment

The shallowest form of commitment is political. It involves committing to ideas or actions when we have little or no drive to follow through because our motives have less to do with the object of our commitment, and more to do with what we might gain or avoid by offering the commitment itself. Political commitment appears in organizations when a person accepts an assignment, not out of any special feeling about its importance, nor because it seems a very good idea, but out of a desire to appear to be a “good soldier,” or to get a “ticket punched” for a better assignment, or out of fear of retribution should they refuse. For example, a man who was the marketing manager for a line of food items that were, by his own admission, vastly overpriced and contained no nutritional value, was doing his job well because success was a certain route to a promotion. His commitment was not to the work itself but to career advancement. Political commitment also appears in personal life when we avoid speech or behavior merely because they are considered “politically incorrect” or when we take on the trappings of the moment because “everyone is doing it.”

Political commitment is the basic fuel of most organizations. People are generally attracted to working in organizations by such promises as “good pay,” “great benefits,” “opportunities for advancement,” and “a pleasant work environment.” These are all good things to have, and the nature of working for an organization involves employees pledging to perform an honest day’s work in return for them. A lot gets accomplished when those in leadership positions agree to such promises, and political commitment is usually enough to get the job done as long as everything is going smoothly.

Political commitment is usually enough when only lower-order change is needed: when people need to do more of something, or less; when only a small amount of new learning is needed; when an alternative way is sought for doing things that they already know how to do, or when adjustments are made to what already exists. Whenever a change is viewed as a necessary and normal part of the job, political commitment suffices.

A leader whose primary call is for political commitment can usually expect “an honest day’s work for an honest day’s pay,” but not much more than that, and sometimes less. This variety of commitment is frequently halfhearted and short-lived. It lacks the oomph, verve, and sheer stubbornness needed to achieve a challenging common purpose.

Intellectual Commitment

A leader calls for intellectual commitment by asking followers to support a purpose because they are logically convinced of its value. In order to convince them, the leader constructs what cognitive psychologist Howard Gardner calls a “story.” He wrote:

I view leadership as a process that occurs within the minds of individuals who live in a culture—a process that entails the capacity to create stories, to understand and evaluate these stories, and to appreciate the struggle among stories.2

An important component of a leader’s story is a vision of the future. It is a picture that a leader draws for followers—a picture of some ideal future state. The story might also contain a rationale for why the leader’s particular story is better than the story his followers now accept, or why it is better than any particular competing story.

Leaders call for intellectual commitment by both communicating and embodying their stories. The stories related by Gardner’s leaders are about the leader and his followers pursuing a common quest. “Together,” wrote Gardner, “they have embarked on a journey in pursuit of certain goals, and along the way and into the future, they can expect to encounter certain obstacles or resistances that must be overcome.”3

Gardner believes that these stories are primarily about identity, about who the leader is and who the followers might become. One good example of such a leader is Margaret Thatcher, named by Time Magazine as one of the 100 most important people of the twentieth century. Time called her the “champion of free minds and markets.”4 Thatcher’s story was of a new kind of Britain, embracing a dramatic change. She convinced the British (not all of them to be sure, but enough to elect her as Prime Minister three times) to challenge their idea of themselves, to abandon governmental interference and embrace privatization of industry and services, as well as individual initiative. She reportedly told a group of aspiring business people, “The only thing I am going to do for you is make you freer to do things for yourself. If you can’t do it, I’m sorry. I’ll have nothing to offer you.”5

The British at the time were not accustomed to such talk from their leaders. Thatcher was intolerant of the socialism, bureaucracy, and powerful intransigent unions that suffused British society. Her message was clearly a different story from the one Britons had been living.

Intellectual commitment in combination with political commitment can accelerate lower-order change. If a person is politically committed to her work and a good idea presents itself, that idea will probably be pursued.

Emotional Commitment

A leader’s call for emotional commitment is an appeal to gut feelings that compel people to act. Where intellectual commitment is about convincing people, winning emotional commitment is about moving them. Daniel Goleman is a psychologist whose work is about emotional intelligence, which refers to one’s ability to know and manage one’s emotions, motivate oneself, recognize emotions in others, and handle relationships effectively.6Goleman, along with Richard Boyatzis, a professor of organizational behavior, and Annie McKee, an educator and business consultant, explored the significance of Emotional Intelligence to leadership in their book Primal Leadership. The authors make their view of leadership very clear when they state,

Great leadership works through the emotions . . . even if they get everything else just right, if leaders fail in this primal task of driving emotions in the right direction, nothing they do will work as well as it could or should.7

Goleman also points out that the evolutionary development of the human brain has furnished us with primitive and instinctive responses that may be inappropriate for a given situation in the modern world. He wrote, “For better or for worse, our appraisal of every personal encounter and our responses to it are shaped not just by our rational judgments or our personal history, but also by our distant ancestral past.”8

Civilization has developed with a rapidity that exceeds the development of our emotional competence, says Goleman. And because emotions are impulses to act, our actions may be driven by impulses, such as anger, fear, and frustration, that are appropriate only to a time in our distant past. Emotional Intelligence is about understanding this, and also about employing our capacity to exert intelligent management of our emotions and behavior.

According to Goleman and his coauthors, leaders are resonant when they are able to hit just the right emotional chord with their followers so that people feel uplifted and inspired. This resonance in turn amplifies and prolongs the leader’s message. Sometimes that chord begins with the leader’s hope and enthusiasm. But it might also begin when the leader empathizes by tuning into and expressing whatever emotions are present. Either way, says Goleman, “Emotionally intelligent leaders build resonance by tuning into people’s feelings—their own and other’s—and guiding them in the right direction.”9 A leader’s resonance with followers gives rise to emotional commitment.

Just as lower-order change can be accelerated by combining intellectual commitment with political commitment, so too can change be accelerated by combining emotional commitment with political commitment. If a person is politically committed and has strong feelings about a needed change, that change will probably be pursued.

Hearts and Minds Together

David Hollister has thought intently about both intellectual and emotional commitment. He was a high school teacher in the 1960s, who later served nineteen years in the Michigan house of representatives, where he was consistently recognized as a top legislator. In 1993 he ran a successful campaign for mayor of Lansing, and then was elected for a second term in a landslide win. He now leads a new state department on labor and economic growth.

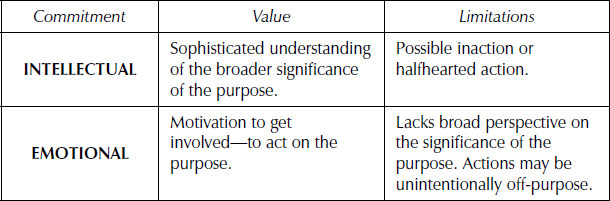

Hollister contrasts those who are intellectually committed with those who are emotionally committed. Intellectually committed people grasp the significance of whatever change is being proposed in historical terms. Hollister wrote, “These people have a sophisticated understanding of the interrelationships, the nuances, and the subtleties of the situation.” People who are emotionally committed have a different air: “Those with the emotional commitment are the traditional activists. They are highly motivated and are anxious ‘to get involved’ to try to change conditions.”10

However, says Hollister, intellectual and emotional commitment each have limitations. The intellectually committed may not be able to move beyond thought and into action. The emotionally committed, lacking broad perspective, may not fully understand the goals to which they are committing themselves and so may engage in action that is thoughtless and off target. Figure 1-2 summarizes the value and limitations of both intellectual and emotional commitment.

So intellectual commitment by itself may breed understanding but inaction, while emotional commitment by itself may produce action that runs amok. However, gaining both intellectual and emotional commitment—winning both minds and hearts—in the service of the same purpose offers the promise of great results. Jacob Bronowski acknowledged this in The Ascent of Man:

Yet every man, every civilization, has gone forward because of its engagement with what it has set itself to do. The personal commitment of a man to his skill, the intellectual and the emotional commitment working together as one, has made the Ascent of Man.11

For sustained change of any kind, other than that of the lowest order, the combination of intellectual and emotional commitment is the minimum commitment needed.

Figure 1-2. The values and limitations of intellectual and emotional commitment.

Spiritual Commitment

There is yet a fourth form of commitment—the most profound form—spiritual commitment. As Figure 1-1 shows, this form of commitment yields the greatest amount of human energy, given the same number of followers. It was described eloquently in a keynote speech to the Mobius Leadership Forum at Harvard Business School by Deepak Chopra, who said,

The leader . . . is the symbolic soul of a group, who acts as a catalyst for change and transformation.12

Chopra defines spirituality as, “A domain of awareness . . . where we experience our universal nature.”13 In this domain we recognize the commonality of all humans at the soul level. This recognition becomes the root of love, compassion, and wisdom—all necessary if a leader is calling for spiritual commitment. For Chopra the magic of leadership is found in the relationship between leader and followers; a relationship in which leaders create followers and followers create leaders.

And so if we understand this principle that leaders and followers cocreate each other, that they form an invisible spiritual bond; that leaders exist to embody the values that followers want, and followers exist to fuel the leader’s vision from inside themselves, then we begin to understand why we see the type of leaders that we see in certain situations.14

Such leadership is rarely seen in organizational life unless the organization itself is inherently spiritual or involves some form of helping. The term “spiritual” is used here not necessarily in the sense of “religious” but in the sense of a calling from some source larger than one’s self. The call may be religious, but might also be from some other entity such as a community, a family, a set of ideals or values, or those who are in need. When we see people whose commitment attains this level, we experience them as “being on a mission.” The mission is usually long-term and sometimes seems to consume the person, as if they were seized by something larger than everyday life. Spiritually committed people give of themselves selflessly and with fervor.

Unlike political commitment, the three higher forms—intellectual, emotional, and spiritual—cannot be bought or sold. They cannot be demanded or coerced. Spiritual commitment in particular evades capture by anyone other than the person who experiences it. It comes from a deeper source than most people bring to their day-to-day work, and from a place within that many people in leadership positions do not touch.

The kind of commitment leaders will attract depends on the depth at which they can tell their stories. If they are competent at articulating an idea in a compelling way, then they will draw people with intellectual commitment. If they are competent at articulating their idea in a way that also comes from the heart, then they will draw the kind of people who have heart for what they are trying to do; those who can offer emotional commitment. If they are competent at articulating an idea that comes from that deeper place within each of us—from the spirit—then they will draw spiritually oriented people who can offer the highest level of commitment. The kind and degree of commitment a leader draws depends upon her competence.

Materials of the Leader’s Art

Those who expect to lead masterfully must be as versatile as was Michelangelo; they must be masters of three distinct art forms. Michelangelo fashioned the Pieta and the statue of David from blocks of raw marble, painted the vaulted ceiling of the Sistine Chapel in the Vatican, and was a primary contributor to the construction of St Peter’s Basilica. He was a sculptor, a painter, and an architect: three distinct art forms. Inspiring intellectual, emotional, and spiritual commitments are each forms of art in the truest sense.

Artists work with their materials and their competencies to provoke a response from others. For example, Michelangelo employed his various materials and diverse competencies primarily to inspire awe and reverence. Leaders, although they work with far less tangible materials than Michelangelo’s marble, pigment, and building matter, nonetheless also employ their various materials and diverse competencies to provoke a response—commitment.

The material used in the art of winning intellectual commitment is a story. The story is much more than merely a vision of what might be, or a tale about a quest for change, but is also a challenge to the very identities of followers. It is a summons to become more than they are, more than they can become by their own solitary efforts. This art calls for four competencies—insight, vision, storytelling, and mobilizing—in order to convince people of the story’s worthiness.

The material used in the art of winning emotional commitment is feeling. This art calls for competencies that are far more subtle and therefore more difficult to master—self-awareness, emotional engagement, and fostering hope. Inspiring emotional commitment entails moving people to go the extra mile to create concrete reality out of abstract purpose.

The material used to win spiritual commitment is soul. Inspiring spiritual commitment is the least concrete of the three arts. The effects of storytelling and feeling can often be seen directly, while the effects of soul as it works in the relationship between a leader and followers can only be sensed in the most intangible ways; some measure of faith is required. Competencies for inspiring spiritual commitment are rendering significance, enacting beliefs, and centering. These are less solid, more numinous talents. Leaders inspire soul in order to engage people more fully and deeply.

A story, feeling, and soul are a leader’s forms of marble, pigment, and building matter. They are the stuff out of which a leader creates art—convincing, moving, and engaging people—inspiring different forms and levels of commitment. The ten leadership competencies, along with the basic material of each and the desired response, are shown in Figure 1-3.

Figure 1-3. Leadership competencies for inspiring intellectual, emotional, and spiritual commitment.

Ten Competencies

The ten leadership competencies form the heart of this book; each is described in a separate chapter, beginning with Chapter 2. Here are brief descriptions of each competency.

Winning Intellectual Commitment

Insight—seeing what is, in a new way. Insight is a perception about a complex set of circumstances that is deeper and clearer than whatever perception prevails at the time. It often comes suddenly. For leaders, insight is most often about the needs or aspirations of a group of people.

Vision—an ideal image of identity and the future. A vision proclaims a leader’s commitment to work toward an ideal. It serves followers as a touchstone, and as a picture of where they are all going together. It also challenges them to consider who they are and who they wish to become. A vision is a leader’s answer to the question, “What could be?”

Storytelling—presenting the story in an unforgettable way. A leader’s story contains his vision, the rationale for the vision, and ideas about what to do in order to achieve it. The presentation of the entire story must be compelling and inspiring. The leader is part of the story and must “walk the talk” and “be the story.” There is a consistency about leaders—who they are, what they do, and what they say. The story and the person support one another.

Mobilizing—transforming energy into committed action. A well-told story creates human energy. Leaders have three roles to play in transforming that energy into action: enrolling people, educating them, and helping them narrow the broad challenges described in the story into actions that they can and will perform. These three roles are enacted during an extended dialogue between the leader and followers that includes everything that happens between them.

Winning Emotional Commitment

Self-Awareness—attentiveness to one’s self. Emotions, motivations, hot buttons, strengths and weaknesses, style, values, the penchants that derive from the family of origin, and from life experience—all influence any attempt at leadership. Since the very self of the leader is his most potent (and perhaps only) instrument, it is wise to know that self well.

Emotional Engagement—the ability to create a flow of productive feeling between the leader and her followers, and among the followers themselves. Emotional engagement depends heavily upon a leader’s skill at empathy—sensing and prizing the feelings of others. A person knows a leader is empathetic when he feels heard and affirmed—not necessarily agreed with, but understood and accepted.

Fostering Hope—creating the feeling that something desirable is possible or likely to happen. A leader’s ability to foster hope depends upon his optimism; the tendency to believe that right will prevail, that good will triumph over evil, that hope is a fitting response to difficult challenges. The ability to instill hope through optimism is an essential leadership task.

Winning Spiritual Commitment

Rendering Significance—drawing the connections from the leader’s insight, vision, and story to a higher meaning and purpose. By rendering significance to their insights, visions, and stories leaders help people come to full human maturity through the diverse forms of their individual lives.

Enacting Beliefs—translating beliefs and principles into leadership activities, not as a religious statement, but as an endeavor of good leadership that wins high commitment.

Centering—the discipline of bringing in rather than leaving out. In a leader’s contacts with followers, mind, emotion, and spirit are invited in when they show up. Centering is the competency through which a leader brings all of the other competencies together as a seamless whole.

Levels of Change

Along with understanding the nature of commitment, and with mastering the competencies for winning intellectual, emotional, and spiritual commitment, a leader needs to ask and answer the question: What level of commitment is needed to effect the change that I am seeking? The answer is dependent upon the level of change involved. The lowest level of change demands little more than new behavior—doing something better for example, or doing it in a new way, or finding a fix for a problem in an existing system without changing the nature of the system itself. At this level of change, things chug along in first gear. The lowest level of change can usually be accomplished with political commitment, and can be accelerated by either intellectual or emotional commitment.

Higher levels of change involve shifting gears upward. They require learning and looking at things in new ways. The nature of the system itself must change: A society relinquishes dependence on institutions in favor of individual initiative, democracy replaces dictatorship, a life insurance company becomes a full-service financial company, aging people transform themselves into a force for change, an arrogant industry embraces customer service. In changes such as these, a whole new story begins. Rather than applying remedies, something new will be generated. Such change transforms systems: A new lifestyle is adopted, a conversion occurs, the identity of those involved changes, not just their behavior, and the understanding of how the system works is revolutionized. Sometimes, something more than learning is required—perhaps rethinking the very ground of learning, asking how we learn, or adopting a whole new way of learning.

Higher levels of change necessitate challenging old beliefs and adopting new ones, or they offer a test of identity, or they call for the trials and sacrifice that accompany passion. This kind of change requires at least the amalgamation of intellectual and emotional commitment, and perhaps commitment that can flow only from the spirit.15

Self and Situation

There is debate among leaders and leadership thinkers about whether it is possible to construct a list of ideal leadership traits, skills, or competencies, or whether the ability of any one person to lead depends upon the situation in which leadership is needed. The answer to this dilemma ought to reside in science; yet so far science has not developed instruments sensitive enough to catalogue or measure the totality of human qualities and behaviors needed for leadership or accurately described the complexity of any given human situation. Leadership is profoundly philosophical and psychological, and therefore eludes scientific analysis.

The position here is that leadership is an art that can be informed by science. Painters understand the chemistry of paint, photographers, the physics of light, and dancers, the potential and limits of human anatomy—they each know what science can tell them about their art. However, they also keenly observe what competencies, skills, and attitudes their situation requires, what others are doing, what works and what does not. And they spend countless hours practicing.

Think of the competencies that are described here as a suggested color palette for plying the leader’s art. Depending on the purpose of the art and on its subject, each competency might be more or less important from situation to situation. But the three questions the painter asks are the same as those a leader must ask.

1.What does this scene require? A seascape needs a painter who is proficient at capturing movement; a company that must rise out of pain and cynicism will first need a leader who can engage emotionally. A desert scene needs a painter who is proficient at depicting openness; a directionless organization will first need a leader with insight, a compelling vision, and a good story. As the scene changes, the painter needs a different proficiency, the leader, a different competency.

2.Have I developed the competency to do what the scene requires? Honest self-assessment is needed here!

3.If not, how can I develop the competency I need? Each of the following chapters contains specific suggestions for developing the competency the chapter describes. The final chapter gives more general suggestions about developing, honing, and refining leadership.

While reading the following chapters, be alert to those competencies that will enable you to lead in a way that makes the best use of who you are. Note those competencies that will make your leadership more personally fulfilling and that will best suit the organization you lead.

Summary

The commitment that leaders seek and that forms the lifeblood of their leadership, arrives in four forms—political, intellectual, emotional, and spiritual. These forms of commitment combine in various ways to create different levels of energy that can become available to a leader’s purposes, the lowest level being political commitment, the highest level being spiritual commitment. Leaders appeal to higher levels of commitment by practicing the arts involved in inspiring intellectual, emotional, and spiritual commitment, each of which depends upon a different set of competencies.

Notes

1.I came across the four-forms model of commitment many years ago and its origins are lost, at least to me. Variations of the model are used by many authors.

2.Howard Gardner, Leading Minds: An Anatomy of Leadership (N.Y.: BasicBooks, 1995): 22.

3.Ibid, 14.

4.Paul Johnson, “The Most Important People of the 20th Century: Margaret Thatcher,” Time Magazine, at <http://time.com/time/time100/leaders/profile/thatcher.html> (August, 2003).

5.Margaret Thatcher is quoted in Gardner, Leading Minds, 236.

6.Daniel Goleman, Emotional Intelligence (N.Y.: Bantam Books, 1995): 43.

7.Daniel Goleman, et al., Primal Leadership (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 2002): 3.

8.Goleman, Emotional Intelligence, 5.

9.Goleman, et al., Primal Leadership, 26.

10.David Hollister, On Organizing <www.educ.msu.edu/epfp/dh/main.htm>.

11.Jacob Bronowski, The Ascent of Man (Boston: Little Brown, 1973): 438.

12.Deepak Chopra in a speech to the Mobius Leadership Forum annual conference at the Harvard Business School, April 11–12, 2002. <http://www.mobiusforum.org/deepak.htm> (November, 2002).

13.Ibid.

14.Ibid.

15.The discussion of levels of change has its foundations in the various writing of Gregory Bateson about orders of change and of Robert Dilts about logical levels.