CHAPTER 1

The Dawn of Irrelevance

FOR THE OUTSIDERS IT was an uneventful cloudy October Sunday in Washington, DC. Over the weekend, the Washington football team had lost to the New Orleans Saints. Baltimore, another local team from the DMV area, was supposed to play on Monday. No earth-shattering news was making the headlines. Ten months after what some media outlets termed the “insurrection,” American media was still obsessed with the domestic ideological wars. Sound bites from politicians were making rounds. Fights over to mask or not to mask were erupting all over the country. Despite a new wave of Covid claiming thousands of lives daily, traffic in restaurants and shopping areas was increasing. Amazon had started its Black Friday sales early. America had adjusted to a new normal. But unknown to most Americans, a fateful event had transpired that weekend. In contrast with the obliviousness of the American media, foreign media had a field day with the news about that story. As the history of this event will be written half a century from now, it would go down as probably the most solemn and depressing weekend for America. That was when Nicolas Chaillan, former chief software officer for the US Air Force and who oversaw the Pentagon's cybersecurity efforts, announced, in no uncertain words, the surrender of the United States in the artificial intelligence (AI) war against China. He gave an interview to the Financial Times—his first after his sudden resignation in September of 2021—and stated, “We have no competing fighting chance against China in 15 to 20 years. Right now, it's already a done deal; it is already over in my opinion” (Manson 2021). Chaillan's statement did not appear as a warning, or a battle cry, or some inspirational slogan to rise and claim back America's AI leadership. It was a cold, matter-of-fact, and outright acknowledgment that it was already too late to have any hope for sustained American leadership in AI.

Chaillan's capitulating comment came after he had expressed his frustration about the inertia in the government and had resigned by submitting a fierce resignation letter. His tenure with the government had lasted barely three years. Chaillan is a naturalized citizen and had become a US citizen in 2016. That didn't stop him from getting a top position with the government. Upon joining, Chaillan was shocked over the state of technology and saw that as an opportunity to bring about a cultural change. Strong-willed and inspired by a vision of transformation, he began acting as a change agent. But he recognized that the problems were far deeper than what he had thought. AI was being approached as any regular technology. Chaillan gave an account of what was transpiring. The organizational dynamics represented a bureaucratic nightmare. Unskilled people were made in charge, and while money was being spent, the procurement costs were high and funds were being allocated in the wrong areas. Most importantly, AI was not being viewed as a national priority. Before resigning from his position with the government and during a CyberSatGov conference, he had claimed that American national security satellite providers were unable to develop “at the speed of relevance” as they were stuck in the Pentagon's ecosystem. In other words, getting unstuck from the Pentagon's ecosystem implied achieving the speed of relevance.

On Monday morning after the Chaillan news hit the international press, Tom Albert, a friend of the American Institute of Artificial Intelligence and an AI entrepreneur (founder and CEO of MeasuredRisk), video called Al Naqvi (one of the authors), and expressed his frustration. Tom is passionate about creating and mobilizing American intellects to rise and fight back against the Chinese dominance in AI. He is putting together a major initiative to inspire American investors and entrepreneurs to develop more advanced AI capabilities. Tom carries a genuine smile and has a great sense of humor. He jokes frequently and laughs loudly. But his voice changes and his face turns red when he starts talking about the lack of visionary leadership for AI at the helms in America. With his fists clenched and teeth gritting, he complains about how America is self-inflicting this catastrophe upon itself. Several minutes into the conversation, he asked Al Naqvi the name of the book that Naqvi was coauthoring. Al Naqvi responded that the name of the book was At the Speed of Irrelevance, and that made Tom smile and he said, “It would have been immensely funny if it wasn't so tragic.” Tom and Al talked for over an hour, and Tom felt this book will be critical to drive hope and to inspire the nation. Tom is among a small number of Americans who understood what the term “speed of relevance” meant and its profound significance for AI and for the United States of America. America's last hope to maintain its global leadership position—the American AI—was in jeopardy. The great experiment was at risk.

AT THE SPEED OF RELEVANCE

Four years before Chaillan threw in the towel, then secretary of defense General James Norman Mattis issued a document in January 2018. This document was the first open and clear expression of a strategy to confront China's growing power. Titled “The National Defense Strategy” (NDS), it refers to the delivery of performance at the speed of relevance. That was the time when General Mattis and President Trump were still on good terms and President Trump bragged about his secretary of defense. The honeymoon didn't last, as a year later General Mattis resigned and gave a two-month notice. Feeling rejected and ignoring the notice, President Trump ended General Mattis's tenure immediately. Shortly after that, President Trump said that he “essentially fired him” and then in June of 2019 went after General Mattis again and said that he felt great about asking General Mattis to resign and that he didn't like General Mattis's leadership style and was happy that General Mattis was gone (Shane III 2019).

Regardless of President Trump's view about him, what is generally acknowledged about General Mattis is that he was trying to change the culture of DoD. The report signed by him said:

Deliver performance at the speed of relevance. Success no longer goes to the country that develops a new technology first, but rather to the one that better integrates it and adapts its way of fighting. Current processes are not responsive to need; the Department is over-optimized for exceptional performance at the expense of providing timely decisions, policies, and capabilities to the warfighter. Our response will be to prioritize speed of delivery, continuous adaptation, and frequent modular upgrades. We must not accept cumbersome approval chains, wasteful applications of resources in uncompetitive space, or overly risk-averse thinking that impedes change. Delivering performance means we will shed outdated management practices and structures while integrating insights from business innovation. (Mattis 2018)

While work on the American AI had begun before 2016, it was General Mattis's recognition that developing a technology first is not what will lead to America's victory; rather, what is critical is adapting and integrating new technologies. General Mattis was trying to evangelize the term “speed of relevance” to imply a more responsive way of delivering results and eliminating red tape and the typical government inefficiencies. Joe Dransfield analyzed the use of the term in an article that appeared on “The Bridge,” an online publication of The Strategy Bridge, a nonprofit organization focused on the development of people in strategy, national security, and military affairs. Dransfield pointed out that Mattis had also used the term in his written statement to the House Armed Services Committee on February 6, 2018, and described it as his aspiration to move the Department of Defense to a “culture of performance and affordability that operates at the speed of relevance.” In another document, Dransfield explains, Joint Chiefs of Staff General Joseph Dunford also used the term, but his usage seemed to imply improving the decision cycle, prioritizing and allocating optimal resources, and enabling better decision-making. Both Mattis and Dunford, Dransfield contends, used the term “as being an adaptation and an aspiration that is fundamental to gaining competitive advantage” (Dransfield 2020).

The term was instantaneously picked up by other agencies, the DC analysts, and supplier communities and quickly became a buzzword. Dransfield (and Chaillan's later statement) clarified that the US Air Force used it to signify technological transformation. The US Army interpreted it as human aspects of the speed of relevance. “The US Navy,” Dransfield claimed, “tended to use former Chief of Naval Operations Admiral John Richardson's preferred nomenclature of ‘high-velocity outcomes' to cover similar aspirations regarding the speed of relevance” (Dransfield 2020). The Department of Defense referred to their cloud-based computing as an example of speed of relevance. Raytheon placed it in an ad. Government contractors included it in their RFPs. And as often happens with buzzwords, they get talked about so much that they lose their higher meaning.

General Mattis is not an AI expert. Neither is General Dunford. But what was profound in their vision is the power of mission relevant and integrated automation, higher prediction power, faster and more effective decision-making, and highly efficient execution speed—all of these improvements are made possible by AI, and all are necessary to advance AI. They were defining and describing what the American AI needed to be. They were setting a challenge for the nation.

The American AI Initiative Was Born

The “American AI Initiative” is America's strategy and plan to maintain and expand America's lead in AI. It was supposed to be the game changer. It was America's response to a rising threat from adversaries and competitors. It was the need of the hour. It could have been a vision truly based on an unpoliticized America First thinking.

But speed of relevance cannot result from pursuing sporadic AI projects and pushing buzzwords in one or two organizations (for example, the DoD). It cannot materialize by fanning out mindless R&D and blindly pumping money into research without having a corresponding industrialization and economic strategy. In addition to focusing on science and technology, it requires approaching the transformation from an industrialization mindset. It needs building an ecosystem of interdependent technologies and capabilities, a meticulously developed national strategy that is articulated to inspire and mobilize the nation, a favorable economic structure, and an entire economy based on AI. It needs an economy-wide change in all areas of commerce and industry. It requires AI to emerge as a social force that gives energy to the nation.

Three and a half years after General Mattis presented his strategy, a new US secretary of defense under a new administration, General Lloyd Austin, proudly claimed that 600 AI efforts were already underway in the Pentagon and that would accelerate the Pentagon's adoption of AI. General Austin saw AI as somehow related to projects, initiatives, and use cases. And this is where America is continuing to fail in architecting its national AI strategy. America is not thinking big enough. AI is not just a technology—it is paradigm change in the economy, science, society, politics, and human civilization. A change of that magnitude cannot be managed by pushing “projects” and “initiatives.” As any other revolutionary technology, AI also requires developing industrialization plans, supporting infrastructure, processes for social and business acceptance, maps of value creation across sectors and industries, social sensemaking and meaning construction, leadership that inspires the nation, and designs that help with diffusing the technology. But the American AI Initiative had none of that. It was growing up in an orphaned state—and even worse, as a hated and undesirable technology.

Chaillan is right. Retired military professionals with no background or experience may not be able to do it. But neither can software experts, Big Tech firms, opportunistic professors, or leading AI technology experts from top universities. AI planning requires a strategic perspective, and that in turn needs a national-level all-inclusive, sector-by-sector industrialization planning with the singular focus on building American capabilities. Above all, it requires a patriotic positioning.

General Mattis's dream of moving American technology forward at the speed of relevance will stay as an unaccomplished goal until an America-focused comprehensive and integrated AI national industrialization strategy is outlined and deployed. Even if General Mattis had been able to fix the culture of his organization and create efficiencies within the DoD, what about the legacy technology cultures of the government suppliers? What about the influence of Big Tech over policy? What about the inability of the political leadership to inspire the nation and mobilize resources? What about the ongoing meltdown of civility and the rise of the ideological wars in America? What about the daily bot and cyber-attacks where enemies and adversaries are constantly bombarding the US to further divide and weaken the nation? What about the opportunistic and commercialized academia where professors place their own selfish interests above national interests? What about the consulting firms whose bread and butter are long, slow-moving, use case–focused, systems (dis)integration projects? What about the rampant influx of foreign money and influence to distract American attention? And what about the troubled supply chains and an old rotten infrastructure in dire need of replacement? The American AI Initiative needed the right breathing space and a healthy environment to grow—but the nation's ecosystem was not conducive for the spark to happen.

In the absence of becoming a national force and a social phenomenon, the entire focus of the American AI Initiative strategy remained on two things—research and investment in research. As General Mattis said in his report, developing the technology first is not an advantage. America needed to build the industrial capacity, social and business adoption, diffusion, and absorption of the technological revolution at a social sensemaking level. But none of that happened.

If speed of relevance implied competitive advantage, then Chaillan had declared that China has already acquired that over the United States. In 2019, ITIF (Information Technology and Innovation Foundation) conducted a study that concluded that China has already surpassed the U.S. in AI adoption and data, and that China’s trend of steady progress could eventually destroy the U.S. lead (Castro and McLaughlin 2021). If the term meant overcoming bureaucratic inertia, Chaillan enlightened us with the incompetence and bureaucracy that still exists in the government. If the term signified capabilities, Chaillan called the cyber defenses of several government agencies being at a “kindergarten level.” So much for the speed of relevance!

The fact is that four years after General Mattis evangelized the term, Chaillan acknowledged that the reality was much different. Clearly, America was working at the speed of irrelevance—and that was nothing short of suicidal. In the age of AI, comparative and competitive advantages of countries will be determined by their AI technologies. America was already at a disadvantage. The American AI Initiative was already in trouble.

OUR JOURNEY IN THIS BOOK

This book captures the tragic story of American slide to irrelevance. It shows the disaster that engulfed and continues to haunt America today. It is a story of failure of leadership at all levels—and of the flawed execution that came with it. This story is being told with the recognition that America can still bounce back from the clutches of defeat, that America performs best when the nation finds its motivation, and that this will not be the first time that America has risen after being cornered and pinned down. Although we do claim that this will be America's toughest and greatest fight ever, we believe (with Churchill's spirit) this could be America's finest moment ever. With that in mind, we begin the story of how America ended up in this dilemma. We have made two simple arguments in this book.

First, we argue that many problems in America are worsening due to one and one reason only: the failure to adopt AI strategically. Ironically, both the identification of and the solutions to such problems are dependent on AI. Consider the following:

- Supply chains: There are now cracks emerging in the American supply chains. The infusion of automation technology at some levels in the value chain and not at others is creating problems. These problems will likely become out of control. Haphazard deployment of AI is not strategic. The problems are exacerbated by the technological rivalry with China—another problem rooted in the lack of strategic adoption of AI.

- AI deployment is not real: We observe a stark difference in how China is adopting AI and how many US companies, agencies, and industries are approaching AI. What many companies, agencies, and industries are calling AI is neither intelligent automation nor what AI means today. It is very basic automation, and calling it AI is a stretch. This misconception of what AI capabilities are will lead to a decline in competitive advantage and performance potential of US companies and agencies.

- The competitive structure is not favorable: The economic structure and environment should be favorable for strategic adoption of AI. But the American economic structure—which is dominated by a small number of very large firms and individuals with tremendous concentration of power and wealth—is not ripe for strategic diffusion of technology. The dominant investment style in AI is creating a negative innovation environment, waste, and increasing the cost of capital. Ironically, AI is contributing to further concentration of power and wealth.

- The national narrative: Nation-inspiring narratives are the harbingers of fantastic news. They mobilize and inspire nations to do great things. The American AI Initiative is suffering from anemic and conflicting messaging. The social construct and narrative behind the technology are weak. On the other hand, AI ideology–centric narratives are dividing the nation and creating domestic conflict.

- External force: Unlike during the Internet revolution, where America stood as the clear and uncontested leader in the world, today's geopolitical situation is different. The technological leadership is being redefined by global players such as China. With AI, the power of such rivals will increase exponentially.

- The productivity growth: Despite significant investment in AI and years of so-called planning and execution, the productivity growth in America has stayed low. The capital being poured into the technology is not showing results—indicating it is misdirected and misallocated. AI must lead to productivity growth, but that is not happening.

- Knowledge economy: As explained later in the book, AI is not just any technology. It is a technology that creates new knowledge, new science, and new technology. It finds scientific breakthroughs for which theory does not exist. It releases science from the linear model of hypothesis-test-results-theory to the paradigm of test-results-hypothesis-theory. Without strategic AI, the industries will remain malnourished to produce new knowledge and discoveries.

The risks for the entire economy and for the country are increasing. So much so that now it is recognized that China has surpassed America in AI. This means America has failed to strategically embrace the AI paradigm. AI is the key to unlock the potential of the national economy. It is the elixir to understand, solve, and identify almost all types of problems.

The AI magic has already begun. Some economies are performing great, while others are struggling. Schumpeter's creative destruction and the related disruption have already started. The loss of AI leadership to China is now becoming far more visible, and it is showing up in numerous ways.

Our second argument is that we hold the White House's Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) as primarily responsible for America's decline and fall in AI. Throughout this book we cover the story of OSTP's continued failure to provide the true leadership that America needed. The problem was not that the OSTP did not do what it was supposed to do. The OSTP did give America a powerful R&D and federal investment plan. The real problem—which led to America's failure on the AI front—was that the OSTP could not distinguish between a national strategy of AI and the R&D-centric federal investment strategy of AI. The OSTP overplayed its hand, assumed the role of a strategic economic advisor, acted in the capacity of an industrialization expert, created a massive deception about its role and plans, intentionally or intentionally (we do not know) covered up hugely relevant information, and completely ignored the process of how strategy (national or business) is developed. In doing so the OSTP forgot its core mission: first, to provide the president and his [her] senior staff with accurate, relevant, and timely scientific and technical advice on all matters of consequence; second, to ensure that the policies of the executive branch are informed by sound science; and third, to ensure that the scientific and technical work of the executive branch is properly coordinated so as to provide the greatest benefit to society. Overstepping its mission, report after report, the OSTP made the national investment plan in R&D appear like a national strategic plan. They are not the same.

A legitimate national AI strategy cannot materialize without following a proper strategy development process. It is not a product of one or two brainstorming sessions by a group of scientists, academics, agency heads, and Big Tech VPs. It requires an elaborate process to understand the economic and business environment, study national priorities and understand national goals, analyze relative strengths and weaknesses, identify the stakeholders, assess the mood of the nation, develop narratives and communications strategy, and many other such process steps. Strategy development process, whether for a business or a country, requires following a methodical approach. Strategy and plan development are, of course, well-developed specialty areas with hundreds of years of research, history, practices, and well-established knowledge domains. But the OSTP engaged in none of that. With the groupthink that led to seven (eight, as one was added later) strategies, the OSTP somehow turned what was the R&D plan into a national strategy. This would be analogous to an aeronautical engineer who knows about planes but is not a pilot, trying to fly a commercial flight full of passengers. Three presidents and Congress relied on the strategy and the positioning coming from the OSTP. Legislation was thrusted based on those priorities. Money was allocated. Executive orders were signed. Agendas were pushed. And America was led through a national strategy for AI that was nothing more than an R&D plan. Imagine if a company confused its R&D plan with its overall strategy and ignored all other aspects of strategic planning. As expected, year after year America continued to miss the mark on the greatest opportunity presented to the nation.

Many did not realize what was going on. They confused the R&D plan with a national strategy. Others understood the great error but stayed quiet because speaking out would have meant loss of funds. So great was this self-deception that the raw potential of AI was somehow caged in a meaningless shell of ethics, values, and governance. All those things are critical for AI—please do not get us wrong here. But they have a place, context, and a position in the industrialization and social construction narratives of AI. However, the way it was shoved down the national throat was such that every time someone talked about AI, they felt compelled to discuss ethics and governance as if they were about to do something wrong, evil, sinister, or illegal. It became a guilt trip, almost an aversion to embrace technology. Interestingly, most of the ethical problems were coming from the big technology firms—the same firms on whom OSTP was relying for advice and who were sponsoring the OSTP conferences. Professors with commercial interests (or their institutions), who received grants from big technology firms or had personal interests in AI tech firms and who rarely disclosed their conflicts of interest, were the other set of advisors for the OSTP. So, while governance, values, and ethics are essential for AI, it seems very hypocritical that the OSTP was in bed with the same exact firms who were not able to keep their own ethics boards intact, much less to come up with a proper AI governance and ethics strategy. Immersed in the rockstar-like power that comes with being in the limelight, the OSTP czars did not care.

The on-the-ground reality of what was transpiring on the industrial side was laughable. At an industry level American firms continued to lose their competitive advantage. Many companies could not even differentiate between what intelligent automation was vs. just plain old automation. Many couldn't tell the difference between robotic process automation (RPA) and machine learning. For many, chatbots represented their total AI plans. From a military angle, China, Russia, and even North Korea perfected their hypersonic weapons while the American program seemed to have run into problems. Even in areas such as social media, where America always maintained a core advantage, Chinese firms surpassed the American firms. Most importantly, despite all the hype about AI, the American productivity growth did not change.

The OSTP's miscalculation—to turn a national R&D plan for federal investment into some type of national AI strategy—was a blunder and an extreme disservice to America. It also had a cascading effect on other initiatives that came from Congress and government agencies, which further derailed the American AI Initiative. It created a national-level mess that will take years to clean up.

We share the story of the chaos that this blunder has created. Today, America is continuing to feel the aftershocks.

On the domestic front, the so-called American AI strategy was too slow and too flawed. Developed by technologists and professors, it failed to apply the basic strategy development process. To be completely frank, it was never a strategy. It was simply a research funding plan—a way to pump lots of money into top universities—universities from which the developers of those so-called strategies came. Led by researchers and academics, the focus of the American AI strategy has been on research and on funding the research. That created a massive confusion. The research strategy was viewed as a national strategy, and America was misled. The “If you build it, they will come” mindset of American policymakers and the czars of White House AI programs was detrimental to the national interests.

The burden on American AI became overwhelming. The anemic start of the American AI Initiative was now being crushed under the weight of a pandemic, rising domestic tensions, a supply chain meltdown, and escalating geopolitical tensions. There is every sign that the dream will be lost, the promise broken, and the great experiment will come to an end. But there is hope. We explain in the book how the mistakes of the past can be fixed and how a new plan can be architected. We remind business leaders and government leaders of their responsibility. It will not be easy. In fact, this will be the hardest battle that America will ever fight. This will be the defining moment for the country. But it all begins by understanding how and where things fell apart. It begins with self-reflection about what led us to this point.

We then show what steps need to be taken to turn around the future of American AI. We conclude that there is still hope but time is running out quickly.

We have three goals:

Goal 1: We want Americans, at all levels, to understand how powerful and disruptive a force AI is. Our main argument is that the reason China has suddenly become a hot issue for us is because of AI. The proof of that is our focus on banning their AI firms. Notice that we are not banning their coal producers or power companies, despite President Biden’s environmental commitments. In fact, we are not even sanctioning their defense firms that manufacture combat weapons. The focus is only on AI firms. That tells you something.

Goal 2: We want Americans to view AI as a necessary national capability and not some globalized science movement. We point out that Google employees’ walkout is analogous to Alan Turing and his team walking out while working on Enigma (WWII) by claiming that decrypting Enigma would be an invasion of Germany’s priority. In other words, in AI, we are no longer part of a global kumbaya – but instead we must view it as a necessary American capability. That sentiment should not be limited to NSA or DOD, but it should become a larger, more grassroots American sentiment. Americans don’t view AI as such. We believe the national mood needs to change from “AI is a global science movement” to a serious “we must break-the-enigma-like national priority”.

Goal 3: We want to communicate that to make progress in AI we need a national strategy and not a haphazard shotgun approach. Additionally, inspiring the nation and minimizing national ideological conflict will be necessary to make progress. Scientific revolutions are also social revolutions.

WE ARE NOT ALONE

In the fall of 2018 Chinese Premier Le Keqiang made an unassuming statement at the World Economic Forum: “We are aware that China remains a developing country. We still rank at the lower end of the world in terms of per capita GDP” (Hu 2018). Perhaps this self-deprecating humbleness was a statement of fact, or perhaps it was one of those tactics where countries quietly acquire power without being in the limelight or getting noticed. Whatever it was, it was short-lived. To be fair, President Trump drew first blood by responding to Premier Keqiang by tweeting that China is “a great economic power,” followed by Larry Kudlow, his economic advisor, complaining that “China is a first-world economy, behaving like a third-world economy” (Hu 2018). These calls did not come as a surprise for China. Most likely, these claims also did not cause a sudden surge in self-awareness of China about its own power. But apparently, they did compel China to lift the veil of humility and modesty. The giant was not awakened as much as it was forced to come out of the shadows. Lifting that veil did two things. First, it forced China's hand to close the gap between playing big and acting big. Second, like a shock to the system, it created an intense need for self-reflection for America. America could no longer feel as the single all-powerful, dominant nation in the world. A challenger had jumped into the ring. The game was on. The competition had begun. And the years that follow will change the future of the world.

THE WOLF IN PANDA'S SKIN

They call them the wolves of China, and their tactics are labeled as “the wolf warrior diplomacy.” Their wolf fame emerged from their readiness to respond to US claims and policies with assertiveness and aggressiveness not seen in previous Chinese diplomats. Apparently, among a billion-plus Chinese, the wolf warriors have acquired a position of admiration and awe. What was surprising, however, and what demonstrated the internal calculus of China was that even with the US placing some pressure on the Asian country, it had the choice to acquire the David position and frame the narrative as the legendary biblical David vs. Goliath battle. But instead, China decided to emerge from the shadows of obscurity and in a matter of a few months entered the world stage as the Goliath. This upsurge was so strong that it made President Biden's Director of National Intelligence Avril Haines classify Beijing as “a near-peer competitor challenging the United States in multiple arenas, while pushing to revise global norms in ways that favor the authoritarian Chinese system” (Neuman 2021).

The term Warrior Wolf was not without context. A 2015 movie released in China with that title acquired a similar iconic position there as some of the American legendary movies had done in America. Patterned after a mix of Rambo and Red Dawn, the movie depicted Chinese military successfully defending a takeover attempt by foreign forces. The foreign forces shown in the movie were composed of mercenaries who appeared to be Europeans or Americans and spoke English. The Wolf Warrior represented a nation finding its voice. It was as if the country had finally come to terms with its might.

This playbook of specifying a foreign enemy to build nationalism has been played and perfected by many other countries, and China's use of it comes as no surprise. The underlying force that was moving the tectonic plates of Chinese emergence were more than a military movie.

Dr. Christopher Ford, Trump-era assistant secretary for nuclear proliferation, shed light on this issue by pointing to something he terms a “grievance state.” From his perspective, countries can often inspire their populace by giving them an account that is based on historical grievance. He identifies four characteristics (Ford 2019):

Grievance polities share four basic characteristics: (1) a sense of self-identity powerfully rooted in affronted grandeur; (2) oppositional postures to what is said to be malevolent foreign influences; (3) a need for foreign enemies to justify domestic authoritarianism; and (4) a revisionist sense of geopolitical mission in the world.

Dr. Ford's analysis opens the door for further inquiry. Is it not true that almost all countries that find and pursue power do possess some type of grievance against some external force—or at the very least have some type of a populace-motivating narrative? America, Japan, England, Germany, France, Italy—had all experienced some form of narratives that may have met the above conditions at some time in their history. Therefore, what makes China's rise different?

In fact, one can ask that if neither financial power nor military strength are fueling the Wolf Warrior mindset, then what is?

Chinese economic power was not unknown to America. Neither was its military strength. After all, it was not too long ago when America's top consulting firms were beating the “move operations to China” drums. For the past two decades, American executives were hammered to link both sides of their supply chains to China. They were told that the cure for anemic stock prices and sluggish economy was “made in China” and “sold in the US.” Government after government praised the merits of globalization. For American companies, China strategy became the wherewithal to respond to never-ending market expectations for short-term revenue and profit increases. And then came the sudden halt.

Interestingly, other than some relatively minor grumbles, the “made in China” movement did not cause major upheaval in America. America not only enthusiastically embraced the move to the China paradigm, but the nation also convinced itself about the merits of that structure. The country adapted to the service economy, and life moved on for many Americans. As always, those who were left behind from the gigantic shift were forgotten as the collateral damage of the new and exciting global economy.

Almost all the relevant charts produced during that era depicted sharply rising trajectories of Chinese growth as an economy, market, producer, and military power. But none of that caused any alarms. The grievance, whether overt or covert, did not translate into Wolf Warrior-ism by China or lead to defensive maneuvering by America.

THE EMERGENCE OF STRATEGIC CONFUSION

At the dawn of the third decade of the twenty-first century, America found itself in a completely different position. This position was one of confusion about the nature of strategic confrontation with China. Policymakers and analysts seemed baffled as to whether China is an adversary, enemy, competitor, coopetitor, or partner (all these terms have been used by various government officials to describe China). In fact, the state of strategic confusion is so awful that one week China is viewed as a trading partner and an economic competitor and the next week as a potent adversary requiring an allied military response. One week decoupling is pushed, only to be followed by next week's recoupling.

If it was not military or economic power—then what inspired a sudden reaction from America? The answer can be found in an analogy from ancient Rome. Rome built the roads that were eventually used to conquer it. In some ways, as America built the Internet, the roads to conquer the American superpower status suddenly became visible to the adversaries or challengers. They were the digital highways. Traveling on them was encouraged and applauded. And they will lead to something that even the designers of the Internet may not have anticipated.

AI RISES

Perhaps unknown to the policymakers who promoted China-based supply chains, a silent revolution was brewing in the academic and research circles. This revolution was not like any other revolutions known to humankind. It was also not an extension of the digital revolution or the Internet. It was as powerful as evolution itself. It carried a power of disruption never experienced before. And despite its immense capacity to alter the direction and structure of human civilization, its initial goals were set as relatively humble task automations. As soon as deep learning (an innovative AI technology based on neural networks) came to the forefront, it became obvious that the world would never be the same again.

Our fascination about aliens invading our planet is typically premised on some intelligent alien species passing through the colossal enormity of space to find their way to planet Earth. What captivates us is not so much having an adversary that invades us but instead the thrill of discovering that another intelligent species exists besides us. The enjoyment of a sci-fi flix comes from simulating a low-probability event, all while being certain of our safety. As we create intelligence with AI, the intelligent species is not emerging from space. It is being synthetically crafted in our labs. The rise of AI is now certain.

THE UNEXPECTED EMERGENCE

What was perhaps unanticipated was China's sudden rise in technologies that mattered. Apparently, three factors came along as major surprises for analysts.

First, by 2015 it became clear that the next few decades will belong to AI technology. The advent of AI will change the course of human civilization. But despite the evident power of the technology, analysts did not anticipate a major upheaval. People went to work thinking that another new app for their smartphones or another social media website would be the future of technology. Offices churned proposals for legacy software. Tech departments worried about upgrades for CRM or ERP applications. More advanced IT shops fretted about adopting microservices and shared services models. Cloud replaced legacy data centers. Business analytics, data visualization, and business intelligence were considered as state of the art. Defense and business analysts went about their daily business. Government contractors pulsated with winnings and losses of bids for legacy technology. Mesmerized with its own indolence, America was experiencing a calm equilibrium. But this was about to change. Like an unexpected perfect storm, AI emerged on the horizon and held the power to change all sectors and all industries. Everything done before AI seemed like child's play. In the words of Senator Ted Cruz, “Internet will only be remembered as the precursor to Artificial Intelligence,” and “Today we are on the verge of a new technological revolution—that there may not be a single technology that will shape our world more in the next 50 years than artificial intelligence” (Moore 2016). AI is expected to change everything: manufacturing, services, professionals, education, sports, entertainment, industry, government, research, and even science. All of a sudden, the technology whose repeated failure to launch had been a far more notable story than its triumph would abruptly rise as the master of all technologies. Like the power unleashed by a lightning bolt from a surprise storm, no one thought that AI could so easily surge and outflank the established molds of technological structures.

Along with the unanticipated rise of AI came the second factor that analysts did not anticipate. AI would not be the typical US-led innovation that spills over to other countries based on a predetermined and controlled filtering and distribution process. It was quickly recognized that the leadership in technology was coming from other countries as well. Specifically, China, and Russia also became prominent pioneers in the field of AI. With determined leadership to position China as a leading player in this field, Chinese government instituted a long-term strategy. America was no longer the uncontested leader at the helm of this revolution.

Third, the productivity potential of AI was not limited to a single sector—it uplifts the entire economy and creates a productivity multiplier effect that no one could have anticipated. It was productivity on steroids. Not just digital, the digitonomous (digital + autonomous systems) transformation was on the horizon. China, if successful, can now accelerate its path to glory and unseat the United States as the global leader.

President Xi noticed that a strategic gap had opened up. He had two choices—to play the conventional strategic patience game or to openly challenge the American leadership—and he chose the latter. His gamble proved to be pivotal for the future of world. In a reactionary state, America found itself unprepared and shocked at best and beaten and overpowered at worst.

The combination of the three surprises led to a new China on the global stage. The traditional analytical frameworks of the analysts did not see this coming. The counterterrorism agendas and Russian ships in the Arctic Ocean dominated the traditional analyst narratives. Mired by the cognitive dissonance and still recovering from decades of “think global, act local” narrative, America was about to get a wake-up call.

AI AND THE AMERICAN PERCEPTION

Since the Clinton/Gore era, the American psyche was shaped by hammering a perpetual state of excitement about information technology (IT) in our collective consciousness. IT was the field that created international legends and influencers who were worshipped by their global fan bases. The tech leaders enjoyed celebrity status that rivaled that of rock stars, movie actors and actresses, and sports personalities. Ma was seen as much a stateless celebrity as Zuckerberg, Musk, or Bezos. IT was viewed as the innocuous technology to make the world a better place, a unifier, an equalizer, a liberator. From burgeoning middle classes all over the world to democracy movements such as the Arab Spring were all attributed to the Internet. It was meant to be transnational and was supposed to collapse the artificially built national boundaries and walls and to bring people together. It was supposed to create a collective global consciousness independent of national interests. It was expected to be the final nail in the coffin of the Cold War–era nationalism and ideological rivalry. But all that optimism was about to change in a dramatic and abrupt manner.

The concept of AI as a national force to compete with other nations was originally proposed by President Putin, who in 2017 said that whoever reaches a breakthrough in developing artificial intelligence will come to dominate the world (CNBC 2017).

While most people pay attention to the domination part, we think the most important insight from President Putin's statement was the reference to “whoever.” This implied that President Putin was not viewing America as a natural leader in AI—something he should have done given that America was truly a pioneer and leader in AI at that time. But Putin's statement was architected to signify that America will not be the unconditional crowned king of the AI dominion. America, like others, will have to fight for the first place. It signaled the beginning of the competition.

When Google's employees walked out to protest the firm working with the government, they were not thinking in nationalism terms; they were being responsible global citizens, patriots of a globalized world, in service of the collective humanity. Americans, especially the technology professionals, did not see AI as a national force or a country-specific capability. It was supposed to be for the world.

From the inception, the American AI Initiative was facing an uphill battle. The American public was under the spell of the IT's globalization narrative. Despite AI clearly becoming core to national security and national capability, it is not being viewed as such at the masses level. Americans remain oblivious to the link between their security and AI. They fail to understand the connection between their prosperity, livelihood, well-being, way of life—and AI. This relationship has not been explained to America.

This makes developing an AI strategy harder. Not only one has to shift the national attention away from viewing technology as some type of global kumbaya bandwagon but also hammer in the idea that it is okay for America to embrace this dual-purpose technology with applications in both civilian and military areas.

THE AMERICAN AI DISASTER

The failure to build a comprehensive American AI strategy has left America in shambles. From a supply chain that has imploded to a nation at war with itself and rampant inflation leading to economic hardships, all can be attributed to America's failure to emerge as an AI leader. From a distance these factors seem unrelated, and AI simply looks like any other technology that will eventually find its way in America. But from up close they all look like part of the same problem: the failure of the nation to embrace AI at the speed of relevance.

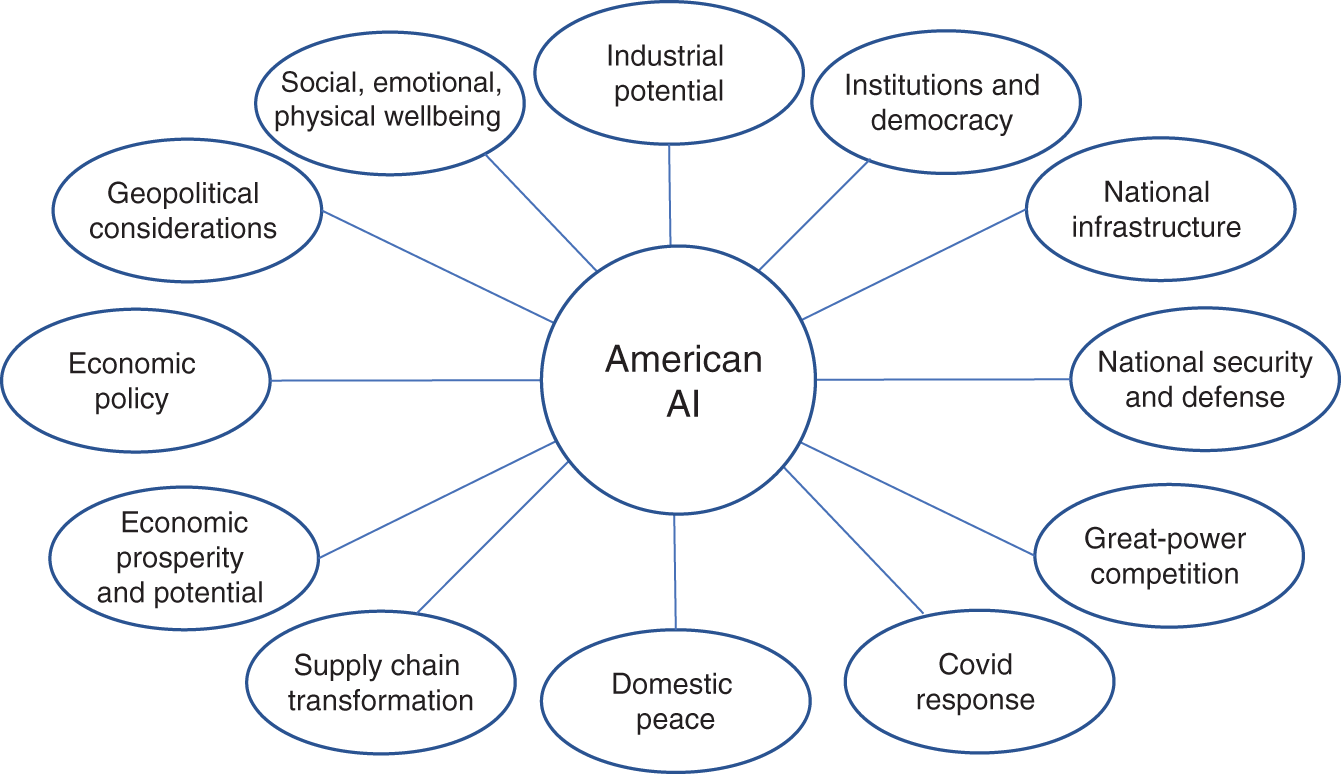

Consider the following problems (see Figure 1.1):

- Supply chain problems: They arose out of rapid changes in demand patterns as well as lack of flexibility and resiliency of the supply chain. The rise of AI-centric e-commerce has shifted the demand patterns. Failure of the existing models to identify the demand patterns and understand the disruptive nature of explosive demand implied that new and powerful AI-based demand forecasting models were needed. This could have been achieved by deploying AI. The supply shocks are also related to the policy of decoupling from a China-dependent supply chain and the Chinese advances in technology where they are successfully exploiting the AI to revolutionize manufacturing and industrialization. This too is a direct consequence of AI competition. By becoming uncompetitive, America had no choice but to retreat and rebuild supply chains independent of China. If America had stayed as a leader in AI, there may have been less need for such a major alteration.

FIGURE 1.1 The AI Span

- Inflation: The inability to apply AI to study the effects of monetary and fiscal policies on the American economy led to policy development that eventually triggered uncontrollable inflation. When combined with the inability to predict demand patterns, the government was unable to deploy an effective policy to manage the economy.

- Productivity: The rising inflation and supply chain disruption can only be countered by a significant and material increase in productivity. But despite being the engine of productivity increase, American AI failed to provide the corresponding increase in productivity growth.

- Military capacity: The ability to build new weapon systems and accelerate defense-related innovation are now greatly dependent on AI. China has reported great success in embedding AI in hypersonic weapon systems and in using AI to accelerate the design of new systems. Whether America achieves the next level of national security and defense capability will depend on American advances in AI technology.

- Domestic conflict: Domestic conflict in America was fueled by the targeted deployment of cognitive bots that shaped the narrative and increased hatred, intolerance, and conflict in America. The inability to protect America against such attacks is largely based on the lack of development of American AI.

- Cybersecurity: With thousands—and by some standards millions—of attacks daily, American cybersecurity infrastructure can only be safeguarded effectively with AI. Only AI gives the power to defend the nation against such attacks.

- Infrastructure: The inability to build and modernize the infrastructure are twofold problems. First is the problem of communications and managing the social narrative for America to understand and support the infrastructure modernization—and to conduct such actions in the best interest of the nation. The hatred, misunderstanding, intolerance, and political bickering spewed by foreign bots has left America in a state of a never-ending internal conflict. Second, rebuilding the infrastructure by using, integrating, and understanding AI is the best way to move forward. Thus infrastructure, smart city designs, highways, buildings—everything can be done more efficiently by using AI, and all such planning must take into account the changes happening due to AI. In the future, when AI is used for such planning, it is possible that the infrastructure investment may turn out to be half of what it was expected. Therefore, AI funding in the infrastructure bill should not be viewed as one of the investment areas, it should be seen as a lens through which all other investments should be determined.

- Covid: The American fight against Covid is based on three drivers: (1) vaccine discovery, (2) protecting populations, and (3) managing the social perception of Covid to increase vaccination and encouraging people to take proper precautions—and AI is at the center of all three. As Lv et al. (2021) reported, the AI played a major role in vaccine development. Managing the disease spread could have employed AI. It was successfully done in China but not in the US. How the social perception and meaning of Covid precaution and vaccination developed were also greatly related to AI. For instance, AI algorithms play a major role in social media where debates about masks and other Covid-related restrictions take place.

Those were some of the examples that show that the American AI strategy cannot be just about research and research funding—it must a broader spectrum of concerns. Most importantly, it needs a strategy development process.

BUILDING AI NATION IN A COMPETITIVE WORLD

Once it was settled that AI is the path to the future and that the competitive advantage of nations will be based on their AI capabilities, America needed a plan to maintain its leadership position: the American AI plan. It was now acknowledged at the highest levels in the government and the private sector that AI capabilities are at the center of progress and those capabilities need focused nurturing and support. It was also recognized that the AI capabilities define the dynamics of the competition with China and that it was not a competitor-less pursuit. The basis of the competition with China was not manufacturing. It was not trade. It was not intellectual property. It was not even military. It was AI and only AI because AI had the potential to change every other factor (manufacturing, services, scientific discovery, and military) in China's favor. In the terminology of The Lord of the Rings, AI was the one ring to rule them all.

America's plan A would have been simply to stay ahead in the AI technology and maintain a large competitive distance with the nearest rival. Had America moved at the speed of relevance, there would have been no need for a plan B.

But as America began to recognize China's swift rise, a plan B needed to be put in place. Plan B would also include countering China's rise. As America scrambled to develop a strategy to counter China's rapid advances in AI, the span of the counterstrategy would not be limited to just technology. It would require deploying the entire power structure of America. Since AI will affect every other aspect of nation building and national capital, both advancement and containment strategies will be needed to counter China's growing influence and capabilities.

The current American AI plan (plan B) seems to be divided into two main strategies:

- 1: Contain the Chinese technological prowess and expansion;

- 2: Strengthen the domestic American AI capacity (roughly the OSTP's co-called national AI strategy).

Strategy 1 would be played at the international stage, and there are indications that it was designed to create the following advantages:

- Increase the cost of business for China;

- Create strategic diversion and confusion;

- Slow down or retard Chinese technological expansion.

The goal of the policy appears to be to rein in and reduce Chinese power and not necessarily to start a new cold or hot war. The American policy related to strategy 1 was clearly articulated and defined.

Strategy 2 was domestically focused to develop an AI strategy for the nation, making investments, driving research and development, and building the industrial base.

Note that strategy 1 only became relevant due to the notable failure of strategy 2 in America. Strategy 1 belongs to plan B, and that, it appears, would have been invoked only if the competitive distance between America and the nearest competitor became alarmingly short. Otherwise, there was no need to shift the geopolitical agenda from a state of equilibrium to a chaotic realignment, which carries significant political and other risks. But by that time the American hands were tied. There was no other way to confront a rising competitive threat. The complacency and reckless negligence on the domestic front had cost America its leadership position. Plan A had failed. And that would lead to unpredictable and consequential geopolitical ripple effects.

While we will lightly touch on strategy 1 in this book, our primary focus is on the domestic strategy. We believe that while China's technology containment strategy is at least meeting the expectations set by the policymakers and belongs to an area where America has considerable experience, the domestic strategy is where America is failing terribly. Our focus will largely stay on that.

JOIN US IN THE JOURNEY

Our narrative has several sides to it. We tell the story of how America dropped the ball on the most critical and consequential change that has ever taken place in the world. Through that reflection we show the gaps that must be closed. Our tone is critical, and at times readers will experience our frustration. But we firmly believe that this is what America needs: a dose of reality and truth. With that goal in mind, we take you on a powerful journey of transformation. In this journey you will experience, see, and hear the stories about the decisions, ideas, strategies, and policies that shook America to its core and that led to American disappointment in AI. You will feel pain, anger, and frustration. You will learn what factors contributed to it, and you will also experience a bit of disillusionment. Through this experience, we hope to inject a sense of urgency, reality, and confidence in America. We hope that our leaders will pay attention to our advice.

Every American has a role to play in rebuilding the national capacity. This could be the most patriotic book you will ever read because it is not driven by political ideology.

REFERENCES

- Castro, Daniel and McLaughlin, Michael. 2021. “Who Is Winning the AI Race: China, the EU, or the United States?” [Online]. Available at: https://itif.org/publications/2021/01/25/who-winning-ai-race-china-eu-or-united-states-2021-update.

- CNBC. 2017. “Putin: Leader in Artificial Intelligence Will Rule World.” September 4, 2017. [Online]. Available from: https://www.cnbc.com/2017/09/04/putin-leader-in-artificial-intelligence-will-rule-world.html.

- Dransfield, Joe. 2020. “How Relevant Is the Speed of Relevance?: Unity of Effort Towards Decision Superiority Is Critical to Future U.S. Military Dominance.” The Strategy Bridge. [Online]. Available at: https://thestrategybridge.org/the-bridge/2020/1/13/how-relevant-is-the-speed-of-relevance-unity-of-effort-towards-decision-superiority-is-critical-to-future-us-military-dominance.

- Ford, Christopher. 2019. “Ideological ‘Grievance States' and Nonproliferation: China, Russia, and Iran.” US Department of State. [Online]. Available at: https://2017-2021.state.gov/ideological-grievance-states-and-nonproliferation-china-russia-and-iran/index.html.

- Hu, Krystal. 2018. “China's Premier Reminds the World: ‘China Remains a Developing Country.'” Yahoo Finance. [Online]. Available at: https://www.yahoo.com/news/chinas-premier-reminds-world-china-remains-developing-country-145413881.html.

- Lv, H., Shi, L., Berkenpas, J. W., Dao, F. Y., Zulfiqar, H., Ding, H., Zhang, Y., Yang, L., and Cao, R. 2021. “Application of Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning for COVID-19 Drug Discovery and Vaccine Design.” Briefings in Bioinformatics, 22(6). Available at: https://doi.org/10.1093/bib/bbab320.

- Manson, Katrina. 2021. “US Has Already Lost AI Fight to China, Says Ex-Pentagon Software Chief in Washington.” Financial Times. October 10, 2021.

- Mattis, James. 2018. “The National Defense Strategy.” Department of Defense. [Online]. Available at: https://dod.defense.gov/Portals/1/Documents/pubs/2018-National-Defense-Strategy-Summary.pdf.

- Moore, Andrew W. 2016. “Subcommittee on Space, Science, and Competitiveness Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation United States Senate Hearing on ‘The Dawn of Artificial Intelligence.'” [Online]. Available at: https://www.commerce.senate.gov/public/_cache/files/12eb9bc7-f5d5-4602-b206-113d6bf25880/B3C3D677FA18E98D85C616AF8326CEE0.dr.-andrew-moore-testimony.pdf.

- Neuman, Scott. 2021. “Intelligence Chiefs Say China, Russia Are Biggest Threats to US.” NPR [Online]. Available at: https://www.npr.org/2021/04/14/987132385/intelligence-chiefs-say-china-russia-are-biggest-threats-to-u-s.

- Shane III, Leo. 2019. “Trump insists he fired Mattis, says former defense secretary was ‘not too good’ at the job.” Military Times [Online]. Available at: https://www.militarytimes.com/news/pentagon-congress/2019/01/02/trump-insists-he-fired-mattis-says-former-defense-secretary-was-not-too-good-at-the-job/.