8

How Facebook Beat Google

LESSON 6:

Crossing the chasm is the best defense.

Background: Before you attack your competition—or are attacked by them—you have to understand each other’s state of adoption among your customers and plan accordingly.

Facebook’s Move: When Google came after them with a similar product, Facebook understood it had the advantage of having “crossed the chasm” with consumers. Instead of panicking, they doubled down on their strengths in the face of Google’s attack.

Thought Starter: What is the state of adoption of your offering? What about that of your competitor(s)?

By the beginning of 2011, Facebook had vanquished the likes of Friendster, MySpace and Twitter, but comparatively those were the minor leagues of the Internet, and word was out that 800 pounds of Google were about to come after Facebook in earnest with a full-fledged social media offering called Google+ that would launch in the middle of 2011.

The natural instinct for describing a Google-vs.-Facebook conflict at that time would be to reach for the David and Goliath trope, but the reality was much darker for Facebook. Depending on your biblical interpretation, Goliath was between 6 feet 9 inches and 9 feet 9 inches and David about 5 feet 3 inches. Nothing like the actual difference between Google and Facebook, which was more like the difference between NBA center Shaquille O’Neal and a kitten.

At 24,400 employees, Google had nearly 12 times Facebook’s 2,127.1 (See Figure 8.1.)

Figure 8-1. Employees (end of 2010)

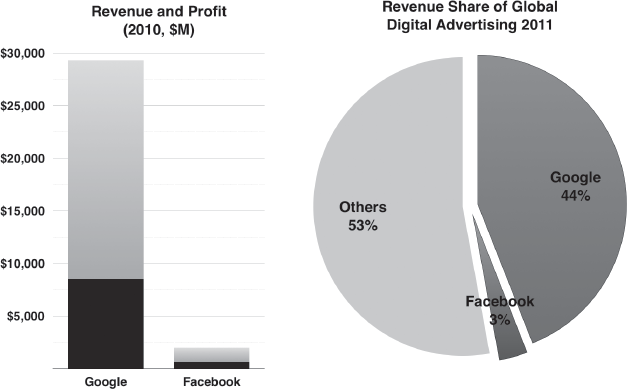

On the business front, Google commanded 15 times Facebook’s annual revenue at $29.3 billion vs. $1.974 billion and 14 times the net income at $8.5 billion vs. $606M.2 Yes, Google’s profits were four times greater than Facebook’s revenue. (See Figure 8.2.)

Figure 8-2. Revenue, profit and revenue share of global digital advertising

In 2011,3 Google would not only have a monopolistic 85% share of search advertising but a 44% share of all digital advertising. Facebook’s share? A minuscule 3.1%.

There was no way around it. As well as Facebook had done, this would be another level of competition entirely.

Everything at Stake for Facebook . . . Nothing for Google

Although coming into the head-to-head confrontation Google clearly outdistanced Facebook on business metrics, the two held more equal roles in the minds of people: Google as the leader in search (3.6 billion searches per day4) and Facebook the leader in social media (608 million monthly active users5).

The problem for Facebook was that if Google beat them at social media, there would be nothing left for them since Facebook at that time lacked other assets to fall back on.

Much less alarmingly for Google, if their incursion on Facebook failed, Google would simply remain the highly profitable Internet leader they already were.

These were the highest possible stakes for Facebook, and Google was very serious. It had begun in earnest in March 2010 when famed early Google employee and vice president of engineering Urs Hölzle penned a manifesto—dubbed the “Urs-quake” inside Google—pointing out the importance of the shift to social on the Internet and the need for Google to invest significant resources in making their products more people-centric. After campaigning heavily internally, Microsoft veteran and Google engineering leader Vic Gundotra was given the reins of the effort and moved to report directly to Larry Page, who had retaken the CEO role from Eric Schmidt in April 2011 and wasted no time in announcing to all employees that the company’s success in social would affect 25% of everyone’s bonus program.

Contrary to significant prior Google efforts that had grown organically with at most a few dozen employees, the Google+ effort would touch over a dozen products and more than two dozen teams comprising by some estimates as many as 1,000 people, many of whom worked in a building entirely dedicated to the effort.

Google had stumbled in prior efforts in the social space, whether in-house or through acquisitions or industry coalitions. Acquisition failures included their rejected offer to buy Friendster in 2003, not maneuvering photo service Picasa into a commanding position after the 2004 acquisition, never launching products based on acquisitions of the Dodgeball location service between 2005 and 2009, the Twitter-like Jaiku between 2007 and 2009, or the social Q&A service Aardvark in 2010 and not growing social app developer Slide after the 2010 acquisition. Failed in-house efforts included social media service Orkut, which launched in 2004 and grew to notable success only in Brazil, the confusing Wave from 2009 to 2010 and the troubled Gmail extension Buzz in 2010. As for industry coalitions, the OpenSocial API, designed to allow the portability of people’s information between different social services, was never able to get Facebook on board and consequently withered.

None of that mattered now. Google+ was just the kind of focused, company-wide, everyone-rowing-in-one-direction effort Google needed to win.

And the pressure on Facebook was starting to show. In May 2011, Dan Lyons writing for Newsweek’s The Daily Beast, exposed the fact that Facebook had secretly hired top global public relations firm Burson Marsteller—known especially for their crisis-management expertise—to prompt negative stories about Google’s privacy practices in various media outlets including USA Today. The episode was an embarrassment for Burson Marsteller CEO Mark Penn, who had run Hillary Clinton’s 2008 presidential campaign, as well as Facebook COO Sheryl Sandberg and her policy and PR chief Elliot Schrage, both of whom had worked for years to improve Facebook’s perception of being trustworthy precisely on issues such as privacy.

Fixin’ for a Fight

So, as summer 2011 neared, Google and Facebook prepared for their showdown.

Zuckerberg’s handling of the circumstances is a good window into his general approach. He balanced a continued commitment to Facebook’s mission and existing product plans with an elevated attention to focus and shipping products that was borne of a healthy paranoia—learned from leadership role model and former Intel CEO Andy Grove—about the increased competition Facebook would soon face. While he did call a “Lockdown”—60 days of redoubled focus that had its origin in tamping down competition at specific colleges in the early days of Facebook and was signified by a red neon sign above his conference room—and moved resources to key projects, there was no wholesale reshuffling of priorities or endless hand-wringing and dithering among Facebook’s leadership team.

Democracies and consensus are not always optimal for nimbly and fearlessly responding—but not overreacting—to a threat. Zuckerberg’s strong leadership (his strength of vision and historical success rate causes everyone at the company to gladly afford him a degree of paternalism that borders on being one of the most effective benevolent autocracies ever) prevented Facebook from losing the script in the face of very real danger.

Throughout the summer and early fall, Facebook would play defense in key areas of the Facebook experience in which they could be beaten by shipping high-res photos and a new photo viewer, an evolved Groups app, the integration of Skype for one-on-one video chat and a new version of profiles, dubbed “Timeline,” combined with offense on new features, including the first iOS and Android versions of stand-alone Messenger, the first Facebook iPad app and the Follow function, which allowed you to subscribe to public updates from people—especially public figures—without having to become friends.

Google, in the meantime, was building a serious social media offering that—like Facebook—would have a user profile based on authentic identity, a “Stream” similar to Facebook’s News Feed, a +1 function similar to Facebook’s Like that was also integrated with Google Search to personalize your results and those of your friends, a Photos function integrated with Google’s existing service Picasa and Pages to provide an opportunity for things like businesses to have a presence on the service similar to Facebook’s own Pages. The two unique features of the service were Circles, a visual way to organize friends into groups in order to control who sees what content from you that was developed by no less a Silicon Valley eminence than original Macintosh system software programmer Andy Hertzfeld, and Hangouts for videoconferencing with up to ten people.

On June 28, 2011, Google+ stepped into the arena with a giant product, an equally giant PR blitz, and, after a twelve-week invite-only field trial, a giant blue arrow on their search page advertising Google+, a cross-promotional first for the company. Initial media coverage was positive, especially for Circles and their apparent advantages over Facebook’s approach to managing who among your friends sees what.

Within two weeks of launch, Google+ grew to 10 million registered users—against the convention established by the likes of Facebook and Twitter, Google+ initially did not report active users—to 25 million in a month, to 40 million by October and to 90 million by the end of 2011.6 All along, Facebook kept calmly shipping product while, like a duck fiercely paddling under the water, Sheryl Sandberg and her business teams kept a very close weekly eye on any Google+ numbers they could get their hands on and worked diligently to keep large business customers from becoming distracted with Google+ Pages and losing momentum on their respective Pages—and related advertising—on Facebook.

The year 2011 came to a close without much clarity on what exactly had happened between the two combatants. Neither had obviously won, but neither had obviously lost.

In February 2012, however, things became much clearer. Any potential perceived Google+ momentum came to a screeching halt when analytics firm comScore released a shocking finding: people were using Google+ only 3.3 minutes per person per month, while they were using Facebook for 7.5 hours. (See Figure 8.3.)

Figure 8-3. Minutes used per person per month

Google+ had not become a habit and had failed to pass its own CEO’s “toothbrush test”—being used at least twice a day—which Page himself had reiterated as an expectation for Google’s products on their July 2011 earnings call just after Google+’s launch.

Google+ would never recover. In June 2012, a year after launching and receiving maximum support and focus from the company and Page, Google+ had only 150 million monthly active users. In that same year, Facebook had not only not suffered any losses in its active user base, they had grown faster than Google+, adding about 200 million monthly active users, going from about 700 million when Google+ launched to about 900 million in the middle of 2012. Google+ would evolve in both function and face-saving public positioning into a mere “social layer” across Google’s services like Gmail and YouTube, instead of an engaging destination like Facebook or Instagram. Its two don’t-throw-the-baby-out-with-the-bathwater features—Hangouts and Photos—went on to become standalone applications.

By the time the dust of the heavily anticipated confrontation had settled, Facebook—the kitten to Google’s Shaq—had stood in the ring and not only withstood Google’s best shot but had defended its title and grown stronger.

How was that possible?

Lessons from 1962: Why Google+ Failed

During the development of Google+, the project’s leaders commissioned a mural of a work by 19th-century German painter Albert Bierstadt for their building to remind the teams of the perils and potential of their project. Befitting the project’s codename, “Emerald Sea,” the painting depicted a rocky, frothy and wind-whipped ocean shore break with the conspicuously broken mast of a sailing ship being tossed about. Little did they know at the time that—just like the painting—their efforts would founder at the inhospitable shores of their competitor’s unassailable asset.

Google had lost the Google+ battle with Facebook three years before it even launched.

That failure, it turns out, can be explained with research first made famous over 50 years ago by sociologist Everett Rogers and later extended by Silicon Valley author Geoffrey Moore. It was Rogers who in 1962 first published Diffusion of Innovations, the most extensive consolidation of over 500 studies across sociology, anthropology and geography into how innovations are communicated through certain channels and evaluated and adopted over time within social systems. It’s important to realize that “innovation” in Rogers’ context applies to circumstances as diverse as Paul Revere’s April 18–19 1775 midnight ride (and the much less successful ride that night by William Dawes), the spread of kindergarten from Germany to the rest of the world between 1850 and 1910, the adoption of hybrid seed corn by farmers in Iowa in the 1930s, the first-businesspeople-then-consumers adoption of cellular telephones in Finland in the 1980s and 1990s, the Internet itself and the social networks of the 2010s.

A crucial distillation in Rogers’ work is the identification of the different kinds of adopters along the timeline of innovations, as well as the surprisingly consistent size of each group as a fraction of the whole target population: 2.5% are Innovators, 13.5% Early Adopters, 34% the Early Majority, another 34% the Late Majority and 16% the Laggards.

It was marketer and consultant Geoffrey Moore who, in his 1992 Crossing the Chasm, expanded on that part of Rogers’ work to identify the significant gap—the titular “chasm”—that exists in adoption behavior between the grouping of Innovators and Early Adopters (the first 16% of diffusion) and the grouping of the Early and Late Majority. He pointed out how difficult it can be to cross that chasm and the natural protection against later competitors (think of the chasm as a moat) that can result if you do.

Academic as that all may sound, it becomes very real when we take a look at Facebook and its diffusion among Internet users as a target population.

We can see in Figure 8-4 that, during 2009, Facebook crossed the proverbial chasm to exceed 16% diffusion and that by 2011 it had diffused through half of the early majority of Internet users globally (and had reached a total of 68% in the United States and more than 90% in countries like Mexico and Indonesia). Consequently, when Google launched Google+—a very similar product to Facebook’s—in the summer of 2011, it did so into the teeth of a competitor who had already safely crossed into the heart of the consumer base and had on their side the switching costs, network effects and petabytes of learnings about 700 million consumers, who had spent up to seven years curating their authentic identity and connections on Facebook.

Figure 8-4. Facebook penetration among global Internet users

There are basically three kinds of players in consumer technology: (1) Those that are unable to cross the chasm in head-to-head competition (e.g., Twitter vs. Facebook), (2) those that innovate and are able to cross the chasm by relating their innovation to the Early Majority (e.g., Facebook in social, Google in search), and (3) those that try in vain to follow—and compete head-on with—existing chasm crossers. Google+ in its efforts against Facebook is the third kind.

For Google+ as it was conceived to have had a chance, it would have had to launch in 2008 while it could still compete with Facebook on the greener playing field ahead of the chasm with an audience of early adopters more open to a new thing.

Alternatively, in 2011, they would have needed to deliver a sufficiently differentiated product that reoriented the playing field enough to allow a newcomer to beat the incumbent the way Facebook beat MySpace or Instagram beat Twitter or Google’s own search beat that of Yahoo. It’s in this shift, however, that a technology company’s greatest strength can become its greatest weakness:

Google was technically and culturally the best in the world at getting you information and moving you onward across the Internet as fast as possible—to this day they proudly tell you just how fast they do so at the top of every search result—while Facebook had become the best at precisely the opposite: engaging you endlessly on their own properties in finding out what was happening in the lives of the people and things you were connected to.

Facebook’s Magic Moment of seeing all your friends and their content—because you were where they were and vice versa—became Google+’s nightmare as shouts of “wasteland” and “ghost town” began to arise not long after the curiosity of its launch had worn off and people returned their attention to the comfortably worn and familiar confines of their Facebook News Feed. Even Google+’s most talked-about feature—Circles—was better in theory than in practice, as people didn’t take the time to build and maintain Circles over time, proving that the burden of getting people the right information from the right people has to be shouldered by a superior algorithm from the network, not the handiwork of its users.

In the end, Google+ lost perhaps less to Facebook than to people’s lack of a perceived need to switch, a cautionary tale for all who think competing in the abstract world of digital must be easier than the hardscrabble world of physical product.

Was there a way for Google to have competed more effectively in the broader social space? Consumer technology may be one of the most difficult environments in which to answer backward-looking what-if questions, but with the luxury of hindsight one can’t help but think that a foray more inherently mobile, more focused on messaging and based on an existing, much loved asset would have had greater success than Google+.

That asset would have been Gmail, which at the time of Google+’s launch had well over 200 million users, would grow to 425 million by the middle of 2012 (when Google+ was faltering at 150 million) and eventually to 1 billion by February 2016.7

Gmail had a built-in map of connections between people (your e-mail contact list), a frequency of use inherent to e-mail at the time (although that’s since been supplanted somewhat by instant messaging) and a natural fit with mobile. Somewhat tragically, this had occurred to Google who in February 2010—more than a year before the launch of Google+—launched Buzz, a Gmail extension that included social features such as sharing links, photos, videos, status messages and commenting but that failed spectacularly when upon launch it triggered a privacy furor as its default settings exposed people’s most e-mailed Gmail contacts publicly, landing Google in a class-action lawsuit and an FTC settlement that would require them to undergo annual privacy audits for 20 years and caused the shuttering of Buzz around the time of the Google+ launch. The Buzz failure—at the worst possible time—essentially destroyed Google’s last best hope for head-to-head competition with Facebook in social.

Apex Predators: The Future of Google and Facebook

The case of Google+’s failure is a window into the rivalry between Google and Facebook. Facebook won that round and in the five years since has become a business of consequence in a similar class as Google’s, leading to the establishment of two suns—and their respective solar systems—largely in control of the Internet.

The two—separated by only four exits on the main Silicon Valley traffic artery US 101—have carved out big leadership positions on opposite sides of the $168 billion 2016 global digital advertising chessboard,8 the fastest growing part of the advertising industry and the part expected to overtake television for largest total spend, starting in the United States in 2016:

![]() Google led in search advertising: 72% share of $29 billion in the United States alone

Google led in search advertising: 72% share of $29 billion in the United States alone

![]() Facebook led in display advertising: 29.3% share of $32 billion in the United States alone, with Google at just 15.7% (and Facebook especially strong in the native and mobile formats that will lead the way in the future)

Facebook led in display advertising: 29.3% share of $32 billion in the United States alone, with Google at just 15.7% (and Facebook especially strong in the native and mobile formats that will lead the way in the future)

While Google’s share of the total digital advertising pie was still a leading—but declining—40% in 2016, Facebook had more than quadrupled their share since 2010 to become the definitive number two at 13.2% and growing.

All of which has led to an uneasy detente.

Google and Facebook are the apex predators in their respective spaces and together are projected to account for a dominant 73% of all additional digital ad spending between 2016 and 2018.9 However, the two have failed to invade each other’s core businesses. Facebook’s effort at search—awkwardly called Graph Search—failed to make a dent in Google’s search business similar to the failure of Google+ in social. In classic Silicon Valley co-opetition, the two even depend on each other. Facebook depends on Google for access to Android-based smartphones, which are the vast majority of the devices dominating the foreseeable future and the apps for which—including Facebook, WhatsApp, Messenger and Instagram—are controlled by the terms and conditions of the Google-owned Play Store. Google, in turn, depends on Facebook—the most important lens on your digital world—for referral traffic, especially to YouTube.

The cautious mutual eyeing is sure to continue. As far as future competition is concerned, over the long term it will be easier for Facebook to invade Google’s turf—beyond brand loyalty, search lacks consumer lock-in or network effects and is powered by relatively commoditized algorithms and merely needs a search box and lots of visitors—than for Google to invade Facebook’s, especially now that the latter has large assets across social media and messaging. While Google may be the very lucrative winner of the past and present, Facebook is its very interesting future.