Effective problem solving

Develop the analytical and creative skills needed to solve any problem successfully

Douglas Miller

Objectives

- You will understand and be able to apply different strategies to help you make better decisions and to identify the pitfalls that can lead to bad decision making.

- You will have learned and be able to apply three key tools to help you implement your decisions.

Overview

Using the five-step process

The problem-solving/decision-making process does not need to be long and involved. For some simple decisions you can work through these five steps in minutes, perhaps even sometimes a minute or less. For others there will be many hours of creation, evaluation and subsequent action. The five steps described in this module provide a logical structure to help you solve problems from the biggest life change to the most minor irritant. Use this process and you will find yourself making better decisions that solve real problems.

The five steps are as follows:

- Is there a problem?

- Defining the problem-solving goal

- Generating ideas to solve the problem

- Selecting the best ideas to solve the problem – decision making

- Decisions into action.

In this module we use four typical workplace problems as a running theme throughout, combined with a variety of problem-solving tools and techniques to help see how they can be resolved better at each step.

Context

Sometimes you might feel that your job consists of little more than solving problems. Some of those problems might not even be your own. But as a manager you are paid to get results and the solving of problems (and the taking of opportunities) is a key ingredient in getting those results. Whether it’s by yourself or with the team, problems and their possible solutions constantly occupy your thoughts. Having an easily applicable process for solving a problem helps you and the team deal with problems quickly and even more importantly deal with the right problems quickly.

If you have career ambitions, so much better to present a problem to senior people with possible solutions rather than being the person who is great at telling everyone what the problems are without having the wherewithal to think what the answers might be. There are a lot of doom merchants, as you probably know. Put yourself above the crowd.

Challenge

- Limiting self-belief. There is much research that tells us that what we realise for ourselves are the things that we are most likely to act on. You have the creative capacity within you to solve the vast majority of your problems with the help and support of others.

- People. Perhaps the biggest cause of problems is the behaviour of other people. Others have needs that may not be the same as yours, but ego and unpredictability play their part too. This doesn’t and shouldn’t stop you working with others to solve your problems. Using the team, with whom you may share some of these problems, allows you to utilise collective wisdom to problem solve. But you must drive the process for doing this. Involving those affected by decisions rather than imposing solutions helps to overcome ‘people’ challenges.

- ‘All I hear are problems!’ Problems are opportunities. This has become a cliché, but like many clichés it has much truth in it. The point here is that your mindset should be that although problems can be difficult and challenging, they also present an opportunity to do something differently, better, cheaper, to a higher quality, more accurately. Be positive about the problem and you put yourself in a better psychological place to solve it.

Step 1: Is there a problem?

Here are a few problems for you to look at as they might be typically expressed in the workplace. In each case try to think how you would know whether it’s a problem:

- Problem 1: you have taken on a member of staff. You feel that ‘he’s not quite good enough’.

- Problem 2: you have difficulties getting on with a colleague who heads up another department. Your view: ‘She’s awkward.’

- Problem 3: decisions are being made that affect you and you currently have little say.

- Problem 4: you aren’t selling enough of product ‘X’.

You can replace any of these problems with some of your own.

The purpose of asking whether there truly is a problem is to try to reduce the influence of subjectivity or gut feeling. Initially, of course, gut feeling is what often starts us thinking. But our assessment of the problem then needs to be based on a more accurate ‘photograph’ of the situation. So, let’s look at some of the possible answers.

- Problem 1: less productivity than previous incumbent; poor timekeeping; comments from colleagues; gut feeling.

- Problem 2: unproductive conversation; arguments; doesn’t meet deadlines that affect you; commits to things and then does nothing; confrontational in meetings; negative body language.

- Problem 3: being ‘told’ rather than ‘consulted’; your job is to be reactive rather than proactive; not being asked to meetings when others are; comments from your own team members.

- Problem 4: statistical tools, e.g. projected vs. actual sales; high stockholding in relation to other products; pressure from the senior team to sell more; customers say they like the product but no one’s buying it.

To help you assess whether there is a problem, use some or all of the following for evidence gathering:

- You have a specific standard and it’s not being met.

- Previous experience – what’s happened before isn’t happening this time.

- More than one person is saying there’s a problem (beware the ‘sample of one’).

- Statistics. Bar charts, Pareto analysis, histograms, etc. are great for comparative analysis and in some instances for visually seeing whether a potential problem exists.

- Behaviour in others that makes you feel uncomfortable.

- Complaints.

- Gut feeling. Shouldn’t be underestimated but try to justify your assessment of a problem in more specific terms to others in your organisation.

TIP

Gathering evidence is important – a lack of evidence will reflect back to you in later steps. Say, with reference to problem 2, you decide to talk to the colleague you find ‘awkward’. Without any specific examples you won’t get very far. It would be so much better to say, ‘When you folded your arms and raised your voice at last week’s meeting it made me feel…’ than in response to ‘Why do you say I’m awkward?’ you say, ‘Well, I just think you are.’

POTENTIAL PITFALL

Are you sure you have a problem? It’s easy to fall into the trap of creating false problems. Say, for example, you sell 50 products. You notice that five of them have sold badly in the last six months, after having sold well in the past. It might be a problem and so you might decide to increase your marketing spend to boost sales. But it might be that the five products are well past their viability in the marketplace and that actually any sales at all are a bonus.

ASSESS YOURSELF

ASSESS YOURSELF

Are you struggling to define a problem? Could it be because you haven’t gathered sufficient evidence in this step?

Step 2: Define the problem-solving goal

If you define the problem correctly then the solution often reveals itself so much more easily. To start, however, you need to be clear on what type of problem you have.

Problem types

You need to recognise what type of problem you have so that you can make appropriate arrangements for defining the problem-solving goal and creating the right conditions for solving it. Recognising the problem type will help you put in place the right kind of thinking to generate ideas for solving the problem and to come to a good decision. There are three types of problems.

Problem type 1: cognition problems

Cognition problems occur where there is a single answer or a limited number of possible answers. Too often we seek the wisdom of the one person we think has real insight, when consulting the group might deliver the best solution. However, we should also note that the right answer may only be revealed once it has been enacted, e.g. how many people can you get in a Mini? Interestingly, if you ask 20 people this and take an average of the estimates, you will be close to the real answer. Your management style should be collaborative in problem solving.

TIP

Use collective wisdom even in a situation where there are limited possibilities; don’t just chase the expert. If a group is working on a cognitive problem make sure it is cognitively diverse – experts, non-experts and all points in between. Encourage independent thinking – independence will bring information and data outside the collective knowledge of those who are already well connected.

POTENTIAL PITFALL

Don’t insulate yourself/selves from outside thought.

Problem type 2: coordination problems

These problems are usually based around a number of people who have a common goal but whose activities need to be synchronised so that this goal is achieved. They need to coordinate their behaviour with each other. Many of our workplace problems are coordination problems. Our second example of a problem – not being part of the decision-making process – could be a simple cooperation problem if the reasons for not including you are less about the vanity of the decision makers themselves and more just about absent-mindedness or lack of consideration for your feelings.

TIP

Solving coordination problems

- Generate lots of ideas – it’s easy to assume that complex problems are cognitive problems and therefore come up with a limited number of possible solutions.

- Group wisdom – as with cognition problems, it seems that the collective wisdom of the group often delivers the best solution.

- Collecting opinions – use an aggregation method to pull together different views. Recording different views in minutes, using intranets and using internal online networking tools are methods for doing this.

- Ground rules – for example, we agree to input with no guarantee that our solution will be co-opted, but the process of both talking through problems and reaching decisions must be fair.

- Core behaviours – valuing ‘soft’ skills, particularly good listening and questioning skills.

POTENTIAL PITFALL

Solving coordination problems

- Avoid ‘groupthink’ – the longer a team is together, the more inclined its team members become to think alike. It’s easy to ostracise independent thinkers because they don’t fit in with the norm. Devil’s advocates and genuinely independent thinkers have an important role to play.

- Avoid ‘head office’ syndrome – get the views of those closest to the problem. ‘Head office’ syndrome means that consultation isn’t decentralised – which it should be. Don’t impose solutions on those closest to the problem. Learn to collaborate and make sure you fully involve those affected by any possible solution.

Problem type 3: Cooperation problems

Cooperation problems occur where individuals have a personal agenda, which may make it difficult for the goal to be achieved – self-interest and distrust are often the blockers here. In our organisations, different teams and departments, although subscribing to common organisational goals (or maybe not!), may have conflicting or counter-productive approaches to achieving those goals. Our second problem – that of the awkward colleague – may well be an example of this, though equally the source of the problem could be simple misunderstandings, which may make it a coordination problem.

TIP

Solving cooperation problems. The conditions for solving coordination problems can be applied here. In addition:

- compromise – reconciling self-interest with group agreement will usually mean compromise

- influence – use influencing skills (your credibility, your reputation, your objective, reasoned argument) to maximise the ‘win’ for you while recognising that others have needs that must be met.

Problem definition

Re-state the problem-solving goal

One challenge is to not let blame cloud your definition of the problem. For example, in problem 3 we see someone who finds that decisions are made that affect him/her where the person concerned has little say. It’s easy to point the finger at the decision makers and say, ‘They have a problem.’ But what if that finger pointed back at you and said, ‘Ok, it’s actually your problem, how can you rethink your perspective on the problem?’ You might therefore reframe the problem-solving goal to say: ‘How can I have more influence over the decision-making process?’

It’s a pro-active goal

Developing further the problem above, you can even be more precise: ‘How can I build my credibility so that I have more influence in the decision-making process?’ (if the evidence suggests that lack of credibility is the problem) is better than ‘stopping people taking decisions without consulting me’. It has a good, active feel – it’s a far more positive statement.

Challenge your assumptions

This is a challenge across all of the five steps. If we refer back to problem 2 – the ‘awkward’ person – you might make the assumption that the other person is the one with a problem. But when you look at the problem you might find that this person’s behaviour is fine with others, it’s only you who experiences what you see as awkward behaviour. Your definition of the problem-solving goal will be very different if the real evidence shows something different to what you imagined it to be.

ASSESS YOURSELF

ASSESS YOURSELF

Lack of solutions in the next step – idea generation – can partly be attributed to two things: lack of clarity in the defined goal and lack of motivation (yours and others) to solve the problem.

Do you feel comfortable generating a range of solutions? If not, have a look at the problem-solving goal again and see whether you need to redefine it. If you find that people are generating ideas and are motivated to solve the problem, it’s a good sign that you’ve worked through this step well.

Step 3: Generating ideas to solve the problem

So, you now have a problem goal that is clearly defined and it is aimed at solving the right problem. You now need to start generating some solutions. Creativity writer and educationist Mark Brown tells us there are three kinds of ideas: 1-D, 2-D and 3-D. In this step we begin by identifying the differences between the three dimensions. We then look at tools and techniques for generating these ideas.

Idea dimensions

One-dimensional ideas

- These are more like ‘habits’ than ideas. Possibly things you do or know already.

- It’s usually the instinctive realm for ideas. We go first to what we know or are familiar with. They are conventional paradigms – a system of beliefs that guides the way we do things.

- 1-D habits are crucial in organisations. They bind your organisation together. An example of a 1-D idea/habit is the way we typically pay people at or near the end of every month.

TIP

With certain kinds of cognitive problems, where there is a single or limited number of possible options, 1-D solutions will usually be fine.

POTENTIAL PITFALL

1-D is good. We need 1-D – if it’s working it may well not need to change. But sometimes we get stuck in 1-D because it’s familiar and comfortable. We dismiss more radical 2-D or 3-D ideas because they don’t conform to the ‘way we do it’. And sometimes a new approach, a new ‘paradigm’, is exactly what we need.

Two-dimensional ideas

- These are what we call ‘evolutionary’ ideas.

- They usually occur when we make a link between similar things that share some characteristics and apply one to the other. Detroit’s Motown records, for example (Stevie Wonder, Marvin Gaye, etc.), the creation of music genius Berry Gordy, modelled its template for creating hit records on the way that vehicles were produced in Detroit’s car-making factories. The ‘likeness’ came from the fact they both had production lines.

TIP

A good question to ask is: ‘Who has their version of our problem and how did they solve it?’

TIP

Think of the way in which, when you join a new company, you want to apply some of the good things that worked in the place you used to work in this new environment.

Three-dimensional ideas

- These are revolutionary ideas.

- They make connections between things that, on the surface at least, do not have any connection. Take the example of the African village that needed a fuel source to pump fresh water out of the ground but couldn’t afford one. To solve the problem they asked the village’s children to play on the village roundabout and connected it to a pump that harnessed the energy created by the children. Result? Fresh water.

TIP

3-D ideas in one generation can quickly become 1-D in the next. Look at what once upon a time seemed radical but is now routine. Does it need another dose of 3-D thinking? Customer service is a classic environment for this. A great new initiative works but soon your competitors are copying and a rethink is needed.

POTENTIAL PITFALL

3-D ideas have a higher risk, at least superficially, because there is usually no precedent.

POTENTIAL PITFALL

3-D ideas are the most highly resisted by others.

Don’t be put off by the number of pitfalls. Of course revolutionary ideas are risky, but nothing ever improves if nothing changes. 3-D thinking is essential.

So, a question you might be asking is: ‘Why do I need to know this?’ There are two primary reasons.

The first is that, when solving problems, it is good to have a healthy mix of 1-D, 2-D and 3-D ideas in most problem-solving situations; not just routine thinking (1-D) but also some more lateral 2-D and 3-D thinking. Note the use of the words ‘most situations’. If the washer on the tap has gone, the 1-D solution is to change the washer. You are probably not going to change the tap as well (though occasionally you might if it’s symptomatic of a bigger problem) or indeed the whole bathroom suite (though once or twice in a lifetime it might be the prompt to do what you need to do – the original suite is looking very old).

The second is that during the next step – selecting the best idea(s)/decision making – you will need to assess ‘risk’. 3-D ideas are clearly more risky than 2-D ideas, as are 2-D ideas to 1-D. But here’s some healthy contradiction: the biggest risk of all might be a 1-D idea. If you have a slow-moving product, an obvious 1-D solution might be to throw more money at advertising it to stimulate sales. But this might be a bad idea if the product has no market or is out of date.

TIP

A team or an individual who is engaged with a problem will come up with lots of ideas – certainly 1-D, probably 2-D and possibly 3-D. This engagement comes from three primary sources:

- Do I feel that my solutions will be acted on – by me/others?

- Do I have a stake/interest in the success of the solution?

- Am I being encouraged to truly participate – are my ideas valued?

Generating ideas for individuals and teams: tips and pitfalls

The goal

We have already emphasised the importance of a clear goal. Don’t be afraid to go back and re-phrase the goal if you feel it isn’t a reflection of what the real problem is. If you find a lack of ideas coming forward in this step it might be because the goal is a passive rather than an active one (see previous ‘step’).

The ‘mental dimmer switch’

You can’t idle your way to insight. However, ‘forcing’ yourself to come up with solutions can be counter-productive. We are often at our least imaginative when under pressure. Consciously disengaging from a problem for a time can declutter the mind and help it return to a more relaxed state. Think about when you have your best ideas: in the bath, on a bike, out walking, in the toilet? Probably not when you are at work and really trying to solve problems. Slowing down the mind can lead to solutions that ‘hard-search’ thinking fails to find. It’s like the way you use a dimmer switch to control lights. Keep the switch on but don’t have the lights burning brightly all the time.

This doesn’t just apply to you individually. If the team has a particular problem and you are getting together to solve it, give advanced notice if you can. A few days of chewing over a problem subconsciously can work wonders.

What if?

A classic trigger for idea generation is the ‘What if?’ question. This could be in the form of a Miracle Question: ‘What if you woke up tomorrow and the problem had been solved? What would success look like?’ But it can also be stated in comparative terms. For example, ‘What if walking into the reception at work was like walking into a forest after it had rained?’ You can start making connections with smell, ambience, peace, colour, etc.

Finite to infinite

Keep playing with ideas. One of the challenges in this step is that we are immediately accepting of ideas as though they have come out of the mental oven fully baked. The fact is that most ideas, when they get put into practice, have advanced considerably from the time they were conceived. So, don’t accept the first idea as finite. Explore it, build on it and search for the infinite ideas that come from a first thought.

‘Piggy-back’ ideas

One technique for this is known as idea ‘piggy-backing’ – jumping on the back of ideas of others using ‘yes…and’ as a link between the first idea and your development of it rather than ‘yes…but’.

Don’t kill…

…the idea. You know how it feels when you hear ‘yes…but’ after you’ve made a suggestion. It’s hard to avoid the temptation to be an idea assassin, but one of the dangers here is that we stop having ideas ourselves if we enter early into critical mode when we are supposed to be free-thinking. This applies equally to groups and individuals. Save the analysis for step 4.

Not invented here

‘Yes…but’ often plays out as ‘yes, it’s an interesting idea, but the reasons we can’t do it here are…’. There’s an assumption made that because the idea isn’t familiar or routine, it won’t work. It may not, but that judgement is better made in the next step.

ASSESS YOURSELF

ASSESS YOURSELF

Unless the problem is a cognitive one (with a limited number of solutions) you can assess your effectiveness by the number of solutions you have and whether there is a good spread across the dimensions.

If you are at the next step but you find yourself going back to idea generation (this is common), it’s a strong indicator that you haven’t exhausted all the possibilities in this step. Curiously, a good indicator that you’ve done well in this step is that decision making might be a little tougher – lots of ideas to choose from!

Step 4: Selecting the best ideas to solve the problem – decision making

If you need complete evidence to make a decision there is a danger that you will never have enough. But the big questions are: ‘How much is enough?’ and ‘At what point do I jump?’ Take time to think about some of the decisions you have taken in the past. Perhaps you moved house – what made you decide to buy the one you did? Perhaps you took a particular course in further education – why did you choose the course you did? Perhaps you like to gamble and play cards – what makes you take the decisions you do when playing?

In this fourth step we are going to look at:

- Factors affecting good decision making.

- The barriers to effective decision making.

- Practical tools for effective decision making.

Factors affecting good decision making

You will probably recognise some of these in your approach to making decisions:

- Experience. What’s worked in previous situations like this? How experienced are you in these situations? Who could you talk to and get the best advice from?

- Risk assessment. What we could lose here will be pitted against the possible benefits. Cost/benefit analysis is a commonly used tool. In project management, ‘critical path analysis’ is used as a means of assessing the key points in any project cycle that will jeopardise the whole project if they fail. Let’s go back to our ‘awkward’ person. Could it be that you can accommodate the awkwardness and not risk damaging the relationship totally by approaching the person about it?

- Intuition. Perhaps the most powerful ‘emotion’ will be your intuition. If we accept that we never have complete information to make the best decision, at some point we have to leap – individually or collectively – into a degree of darkness using intuition as a guide. Intuition can be spectacularly right and sometimes spectacularly wrong. And of course many of the decision-making tools described here, such as experience, help intuition.

- Emotional control. Emotional contamination occurs when your degree of excitement over a possible decision clouds your judgement. You want to move to France? Great! But you don’t speak the language, have any friends or family there and there’s no realistic prospect of a good job.

- Opportunity. If I don’t take the opportunity now, would I ever? We’ve focused on the word problem, but the solving of a problem is itself a great opportunity. Take the opportunities inherent in our four problems identified during Step One:

Problem 1 – the possibility of getting the new recruit up to standard or employing a new, possibly better, person.

Problem 2 – the chance to improve a previously problematic relationship.

Problem 3 – more influence.

Problem 4 – efficient stockholding; improved sales; profitability.

- Other people. Who is in the team – what are their capabilities? How much resistance am I likely to get from others? Who is likely to offer support? This might affect your decision regarding the weak new recruit in the first problem. Can you support him/her with the help of others in the team? Would shadowing other team members help?

- Empowerment. The decision you take may be influenced by the degree to which you feel empowered to put the decision into action. Do you need the authority of others? In our fourth problem there is a big difference between deciding yourself to discontinue a product line and making a recommendation to do so. If you are the sales manager you might suggest to the sales team that they focus their attention away from this product onto lines that are an easier sell, but there might be repercussions in doing so if the decision to discontinue is taken elsewhere.

The barriers to effective decision making

Information weight

Research tells us that in decision making we are inclined to give disproportionate weight to the first information we receive and we bias our judgement accordingly. It could be two things that are as different as a statistic or a first impression someone has of you.

A good example of information weight concerns who we speak to in connection with the decision. Imagine you are trying to deal with your awkward person. You seek advice from a colleague. He tells you to ‘give as good as you get’ and not be so accommodating. He says ‘toughen up’. It’s hard to forget that if it’s the first bit of advice you get, but it might be terrible advice – encouraging you to be confrontational rather than collaborative.

This process is sometimes known as ‘anchoring’. So, check that your decision isn’t being guided by the wrong anchor.

TIP

Imagine that your starting point was different – would you come to a different decision?

TIP

Consult from a variety of sources, including those who have no or little vested interest in the decision you take.

POTENTIAL PITFALL

Don’t pass on your anchor. When talking to others about the problem/decision you can easily bias their advice by the type of information you give them. Imagine it’s that slow-selling product again. You might tell a colleague, ‘We sold two last week’, omitting to tell them that you hadn’t sold any in the three months before.

Preserving the status quo

So once upon a time product X was our best-seller. Now it’s not. But we want the good times back. So let’s keep pushing it. Unfortunately, in this instance a common problem in decision making is the preservation of the status quo – ‘the way we do it’ becomes a straitjacket when the very reason you have a problem is that life has moved on and you haven’t moved with it.

TIP

What to do:

- Push yourself to come up with more options. Don’t convince yourself that the status quo is the only alternative.

- A status quo decision might be the best, so don’t rule it out in the quest for more creative solutions.

- Don’t exaggerate the cost or work involved in switching from the status quo because it makes life easy.

POTENTIAL PITFALL

Lack of time is not a good friend in decision making. It’s tempting just to go for the status quo, but you may well be perpetuating the problem. A little extra time spent now could mean a lot of time saved later.

Confirmation bias

It’s common with first impressions, for example, that we are inclined to look out for all the things that confirm the first impression and ignore the things that don’t fit our initial view. Take the example of the awkward colleague once more. You’ve formed the impression that he or she is awkward. Have you checked to make sure that you are not just looking out for the continuing signs of awkwardness, possibly ignoring other times when his/her behaviour was fine? This is known as ‘confirmation bias’.

TIP

- Examine all of the evidence, not just that which confirms your preconceived idea or your prejudice.

- Argue against yourself. Better still, get someone to argue against you.

- Have people around who don’t just agree with what you say – especially if your relationship is based on formal power, i.e. you are the boss.

POTENTIAL PITFALL

What are your motives here? A classic pitfall is to want to agree with yourself (like the way we read newspapers and political websites that reflect our political opinions).

The people factor

Remember the 2008 financial crash? It’s widely believed that economists failed us because they forgot that economics is a social science – involving human behaviour – and not a branch of mathematics. People don’t always behave the way we think they will behave or the way a computer says we will behave. Being wrapped up in figures, process, risk, systems and procedures can mean we ignore ‘us’. The cooperation-type problems we looked at in step 2 will fail if we do not take into account human behaviour during this step.

Simple problems of coordination can turn into cooperation problems if you don’t talk to people. It’s no secret that on the many problem-solving courses run by this writer, 90% of the problems identified by participants relate to people, not to systems and procedures.

TIP

What to do:

- Use ‘force-field’ analysis (see step 5 for more on this).

- Involve those affected by a decision in the decision-making process to get ‘buy-in’.

- Research says that honesty and empathy combined are the best way to get people on your side when cooperation is difficult to establish. People might not like what’s happening but they might respond better if you have shown that you understand their concerns.

- When assessing risk, have ‘the people factor’ right at the top of the list. What if they behaved differently to how you expect?

- Use ‘we’ rather than ‘me’ where you can.

Practical tools for effective decision making

Hot or not?

Time can sometimes be the best problem solver. Just as we often solve problems that don’t really need solving or aren’t really problems anyway, the same applies to decision making. So the question here is: do you need to turn up the heat and get a decision made now (and often pressure is not conducive to good decision making) or can you chew over the decision for a while? False pressure is often ‘fool’s pressure’.

Must have, want to have, like to have

This technique is really useful if you have a lot of options and you’re finding it hard to see through the fog of unending possibilities. It allows for the quick elimination of possibilities that don’t meet set criteria. Say, for example, that you are buying a particular piece of software for the IT system. There are lots of options in the marketplace. It’s easy to be distracted by software that does a million things, most of which you don’t actually need.

You start by deciding what criteria your acquisition must meet. Not going above budget might be one of them, thereby immediately eliminating all of those possibilities that go above budget. The software must have certain features so that it is fit for purpose. It’s a bit like buying a car; someone who’s retired might not need GPS if all they need a car for is to pop to the shops. A second elimination – the want round – then further eliminates more possibilities. If necessary a third round – the like round – then eliminates more until you are left with one or very few possibilities.

Listen to yourself

Ok – it’s intuition really! Here are some reasons to use intuition combined with pitfalls:

- Intuition can be a valuable sixth sense that tells us if a particular direction is right or wrong.

- Henry Ford once said that if you think you’re right or you think you’re wrong, you probably are.

- With just a few options, intuition can steer us down the right path.

- Experience can improve intuition – good judgement comes from experience. Experience comes from bad judgement.

POTENTIAL PITFALL

- Our intuition can be wrong. Sometimes we need to combine experience, facts, patience and intuition in varying amounts to keep going in the right direction.

- Gut feeling can mean we see the things we want to see and ignore the things we don’t or are blind to.

- Intuition can be mistakenly channelled into ‘fool’s hope’.

Whose decision?

So, what are the limits of your decision-making responsibility? Referring back to one of our earlier problems – the poor performing new recruit – do you need to refer to HR or can you sort out this problem yourself? The more control you have over acting out your decision, the more likely it is to succeed. In the next step you will find it useful to refer to the four-box model to help you do this. Is your decision a recommendation or something you can enact yourself?

ASSESS YOURSELF

ASSESS YOURSELF

The best decisions usually have a balance of ‘head’ and ‘heart’ – the heart to provide the motivation to enact the solution(s), the head to make sure the issues have been clearly thought through. Have you got lots of both?

Perhaps the best assessment you can make here, however, is: ‘Did the decision we took solve the problem?’ If it did, even if it wasn’t the perfect decision and you didn’t follow all the advice to the letter, you can say you have done well.

Step 5: Decisions into action

The tools offered in this final step can be reasonably applied in any of the steps. There are three tools here to help you put your decisions into action. The first, force-field analysis, allows you to assess likely areas of opposition to any decision. The second, the four-box model, allows you to establish where you are free to act on your initiative and where you aren’t. The third relates to you and your attitude to the work you do.

Force-field analysis

This applies equally to step 4 and step 5. In taking a decision (step 4) you need to be sure that you have understood and can overcome people-related issues as part of your assessment of risk. In step 5 you will now be implementing your decision and, again, those people issues will be crucial.

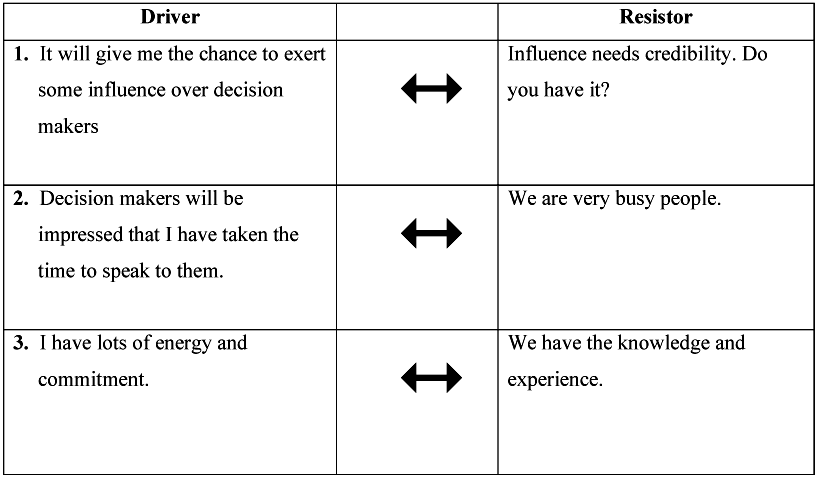

In force-field analysis you make an assessment of the benefits of your solution pitched against the resistance you may encounter at the same time. Just because you see something as a benefit does not mean others will. Force-field analysis allows you to establish where the resistance will reside and then to address these resistors. Below is a diagram that shows how these resistance factors are established. Let’s take one of our original four problems once again – decisions being made that affect you and over which you have little say – and expose one of its potential solutions to force-field analysis. The solution being exposed is that you have decided to arrange a meeting with each of the decision makers individually to explain your frustration.

The key here is that the resistance factor may not exist at all. But if, for example, the resistor in Driver/Resistor 1 ‘Influence needs credibility’ pushes you to work hard at making yourself credible, then it can only help you. Similarly, in Driver/Resistor 3, the possible resistor can push you to draw attention to their knowledge and expertise with a little subtle but gentle flattery – ‘In your experience…’; ‘I would value your input into this…’ and ‘I think you looked at this before, what were the issues for you?’ are all examples of the way in which you might turn the resistor into a relationship-building asset.

By establishing the resistance factors you are now able to create a strategy for overcoming them should they occur.

Using the four-box model (Mark Brown, 2009)

The four-box model helps you to identify the areas where you and/or your team can and cannot act freely in this last step in the problem-solving process. It is designed to do three things:

- It helps establish where you/your team can act on decisions and where decisions have to be referred higher up for approval/enactment.

- It establishes control.

- To be clear where it is ok to make mistakes in the act of trying something new or different and where things have to be tightly controlled.

The four boxes are as follows:

So, how does this work? To understand this we need to know what the boxes mean.

No go

The ‘No go’ box comprises decisions where you are not free to act at all on your own initiative. It provides an important moral compass where decisions are likely to break morals and ethics or breach the values that your organisation holds. Decisions that compromise safety and legality also sit here.

TIP

Where safety, legality, morals and ethics are broken by the decision you need to refer back to the previous step and rethink your decision.

Yes, then go

This is where permission has to be sought, usually from more senior people, to problem solve, make decisions, create, initiate, adapt, change, re-interpret or amend and then act. You need to factor in the benefits of taking the decision you want to take here because you have to influence others to give the green light. Have you/your team thought through the issues, explored the risks and the costs, and are you clear on the people issues? If you’ve been rigorous in step 4 then your capacity to secure agreement will be greater.

Go, then let know

This is where you are free to act on your initiative but you need to let others such as your manager know what you’re doing, how it’s going and what you’re learning. With approval comes the right to make mistakes (although these should be honest mistakes in the act of trying rather than those that breach box 1 rules). Not everything works as you planned it.

Go

Decisions that are to be acted on that can be made without securing the agreement of others and that don’t have to be accounted for sit in this box. This is the complete unfettered freedom you have in your job to do what you want, when you want and how you want. The freedom here includes freedom to make mistakes.

Pitfall: In our enthusiasm to enact a decision we might feel particularly empowered and assume automatically that the decision sits in the ‘Go’ box. Challenge the assumption.

Attitude and the ‘E’ factors

This section could be applied at any point during this module but it sits very well in this final step where your concern will be with putting a solution into action – your attitude when ‘doing’ is vital.

Engagement

True engagement provides the necessary propulsion in this final step. Engagement comes from two factors – what the logical ‘head’ is saying and what the emotional ‘heart’ is feeling. As we have seen, decision making has a clear need to assess fully all the factors that lead us to make the best decision.

Effort

There aren’t many people who don’t want to do a good job, but equally not many give fully of themselves. Industrial psychologists talk of the ‘discretionary effort’ that resides within us. This is the difference between the minimum we can give of ourselves that enables us to get by and the maximum we can give that allows us to fully express our capabilities. We have a choice as to how much or how little of this discretionary effort we give. With 1-D solutions the minimum may be enough to get us through routine tasks. However, the challenge presented by 2-D and particularly 3-D solutions will mean you need to be prepared to give more of yourself.

Empathy

If it’s the people factors that are so important then it’s your ability to climb into other people’s worlds in all the steps – but particularly this one – that is a key variable in success or failure. Solving problems means new ideas. New ideas mean change. And change often means asking people to do things differently. As social pioneer William Beveridge once said:

‘The human mind likes a strange idea as little as the body likes a strange protein and resists it with a similar protein.’

TIP

Empathy is defined as ‘I feel with you’. If you ignore people’s feelings they are likely to ignore you. If your decisions are 2-D or 3-D (William Beveridge’s ‘strange idea’), people will resist, so refer back to force-field analysis as a means of identifying likely areas of resistance.

Key point summary

- Don’t ignore the people issues – they are often the key variable in the success or failure of your decisions.

- What you think is attractive about a decision may be perceived differently by others. Consider all the issues, counter-arguments and losses that may be perceived by those affected.

- How far does your freedom to act on decisions extend? Don’t abuse your position.

- A great attitude makes all the difference!

Success

As a conclusion, the words of a football manager, Juanma Lillo, are really appropriate here:

‘Human beings tend to venerate what finished well, not what was done well. We attack what ended up badly, not what was done badly.’

Not all of life’s problems are solvable right away. This module has given you the opportunity to do something well, to give you the best chance of success as a problem solver. We have emphasised the importance of the right problem-solving goal to start and then worked through a five-step process right through to action. So, a final thought. Goals without action pass the time. Goals with action change the world. Get started!

Checklist

- Do you understand the importance of gathering sufficient information and evidence at the start of the decision-making process? Click here to review.

- Are you struggling to define your problem? Do you understand what you need to think about to define the problem that you are facing? Click here to review.

- Do you feel able to recognise what type of problem you have and confident that you can make appropriate arrangements for defining the problem goal and creating the right conditions for solving it? Click here to review.

- Can you recall the three main types of problems? Click here to review.

- Do you understand why it is crucial not to let blame cloud your definition of the problem? Click here to review.

- Do you feel comfortable generating a range of solutions? If not, have a look at the problem-solving goal again and see if you need to redefine it. Click here to review.

- Can you identify the differences between the three dimensions? Are you confident with using the tools and techniques for generating these ideas? Click here to review.

- Can you recognise the main factors affecting good decision making? Do you recognise some of these in your approach to making decisions? Click here to review.

- Do you recognise the key barriers to effective decision making and how to avoid them? Click here to review.

- Are the majority of problems encountered in the workplace related to people or to systems and procedures? Click here to review.

- Do you understand and feel able to use the three main practical tools that can be used for effective decision making? Click here to review.