Samuel Finley Breese Morse was born in 1791 in Charleston, Massachusetts, the town where the Battle of Bunker Hill was fought and which is now the northeast part of Boston. In the year of Morse's birth, the United States Constitution had been ratified just two years before and George Washington was serving his first term as president. Catherine the Great ruled Russia. Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette would lose their heads two years later in the French Revolution. And in 1791, Mozart completed The Magic Flute, his last opera, and died later that year at the age of 35.

Morse was educated at Yale and studied art in London. He became a successful portrait artist. His painting General Lafayette (1825) hangs in New York's City Hall. In 1836, he ran for mayor of New York City on an independent ticket and received 5.7 percent of the vote. He was also an early photography buff. Morse learned how to make daguerreotype photographs from Louis Daguerre himself and made some of the first daguerreotypes in America. In 1840, he taught the process to the 17-year-old Mathew Brady, who with his colleagues would be responsible for creating the most memorable photographs of the Civil War, Abraham Lincoln, and Samuel Morse himself.

But these are just footnotes to an eclectic career. Samuel F. B. Morse is best known these days for his invention of the telegraph and the code that bears his name.

The instantaneous worldwide communication we've become accustomed to is a relatively recent development. In the early 1800s, you could communicate instantly and you could communicate over long distances, but you couldn't do both at the same time. Instantaneous communication was limited to as far as your voice could carry (no amplification available) or as far as the eye could see (aided perhaps by a telescope). Communication over longer distances by letter took time and involved horses, trains, or ships.

For decades prior to Morse's invention, many attempts were made to speed long-distance communication. Technically simple methods employed a relay system of men standing on hills waving flags in semaphore codes. Technically more complex solutions used large structures with movable arms that did basically the same thing as men waving flags.

The idea of the telegraph (literally meaning "far writing") was certainly in the air in the early 1800s, and other inventors had taken a stab at it before Samuel Morse began experimenting in 1832. In principle, the idea behind an electrical telegraph was simple: You do something at one end of a wire that causes something to happen at the other end of the wire. This is exactly what we did in the last chapter when we made a long-distance flashlight. However, Morse couldn't use a lightbulb as his signaling device because a practical one wouldn't be invented until 1879. Instead, Morse relied upon the phenomenon of electromagnetism.

If you take an iron bar, wrap it with a couple hundred turns of thin wire, and then run a current through the wire, the iron bar becomes a magnet. It then attracts other pieces of iron and steel. (There's enough thin wire in the electromagnet to create a resistance great enough to prevent the electromagnet from constituting a short circuit.) Remove the current, and the iron bar loses its magnetism:

The electromagnet is the foundation of the telegraph. Turning the switch on and off at one end causes the electromagnet to do something at the other end.

Morse's first telegraphs were actually more complex than the ones that later evolved. Morse felt that a telegraph system should actually write something on paper, or as computer users would later phrase it, "produce a hard copy." This wouldn't necessarily be words, of course, because that would be too complex. But something should be written on paper, whether it be squiggles or dots and dashes. Notice that Morse was stuck in a paradigm that required paper and reading, much like Valentin Haüy's notion that books for the blind should use raised letters of the alphabet.

Although Samuel Morse notified the patent office in 1836 that he had invented a successful telegraph, it wasn't until 1843 that he was able to persuade Congress to fund a public demonstration of the device. The historic day was May 24, 1844, when a telegraph line rigged between Washington, D.C., and Baltimore, Maryland, successfully carried the biblical message: "What hath God wrought!"

The traditional telegraph "key" used for sending messages looked something like this:

Despite the fancy appearance, this was just a switch designed for maximum speed. The most comfortable way to use the key for long periods of time was to hold the handle between thumb, forefinger, and middle finger, and tap it up and down. Holding the key down for a short period of time produced a Morse code dot. Holding it down longer produced a Morse code dash.

At the other end of the wire was a receiver that was basically an electromagnet pulling a metal lever. Originally, the electromagnet controlled a pen. While a mechanism using a wound-up spring slowly pulled a roll of paper through the gadget, an attached pen bounced up and down and drew dots and dashes on the paper. A person who could read Morse code would then transcribe the dots and dashes into letters and words.

Of course, we humans are a lazy species, and telegraph operators soon discovered that they could transcribe the code simply by listening to the pen bounce up and down. The pen mechanism was eventually eliminated in favor of the traditional telegraph "sounder," which looked something like this:

When the telegraph key was pressed, the electromagnet in the sounder pulled the movable bar down and it made a "click" noise. When the key was released, the bar sprang back to its normal position, making a "clack" noise. A fast "click-clack" was a dot; a slower "click…clack" was a dash.

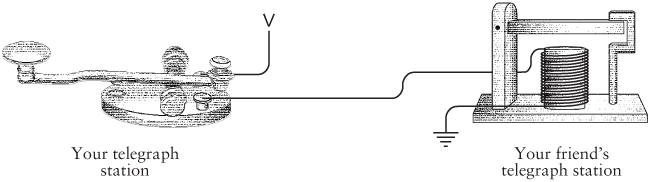

The key, the sounder, a battery, and some wires can be connected just like the lightbulb telegraph in the preceding chapter:

As we discovered, you don't need two wires connecting the two telegraph stations. One wire will suffice if the earth provides the other half of the circuit.

As we did in the previous chapter, we can replace the battery connected to the ground with a capital V. So the complete one-way setup looks something like this:

Two-way communication simply requires another key and sender. This is similar to what we did in the preceding chapter.

The invention of the telegraph truly marks the beginning of modern communication. For the first time, people were able to communicate further than the eye could see or the ear could hear and faster than a horse could gallop. That this invention used a binary code is all the more intriguing. In later forms of electrical and wireless communication, including the telephone, radio, and television, binary codes were abandoned, only to later make an appearance in computers, compact discs, digital videodiscs, digital satellite television broadcasting, and high-definition TV.

Morse's telegraph triumphed over other designs in part because it was tolerant of bad line conditions. If you strung a wire between a key and a sounder, it usually worked. Other telegraph systems were not quite as forgiving. But as I mentioned in the last chapter, a big problem with the telegraph lay in the resistance of long lengths of wire. Although some telegraph lines used up to 300 volts and could work over a 300-mile length, wires couldn't be extended indefinitely.

One obvious solution is to have a relay system. Every couple hundred miles or so, a person equipped with a sounder and a key could receive a message and resend it.

Now imagine that you have been hired by the telegraph company to be part of this relay system. They have put you out in the middle of nowhere between New York and California in a little hut with a table and a chair. A wire coming through the east window is connected to a sounder. Your telegraph key is connected to a battery and wire going out the west window. Your job is to receive messages originating in New York and to resend them, eventually to reach California.

At first, you prefer to receive an entire message before resending it. You write down the letters that correspond to the clicks of the sounder, and when the message is finished, you start sending it using your key. Eventually you get the knack of sending the message as you're hearing it without having to write the whole thing down. This saves time.

One day while resending a message, you look at the bar on the sounder bouncing up and down, and you look at your fingers bouncing the key up and down. You look at the sounder again and you look at the key again, and you realize that the sounder is bouncing up and down the same way the key is bouncing up and down. So you go outside and pick up a little piece of wood and you use the wood and some string to physically connect the sounder and the key:

Now it works by itself, and you can take the rest of the afternoon off and go fishing.

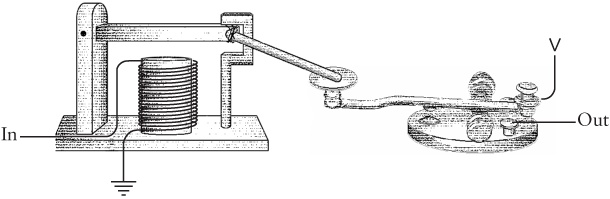

It's an interesting fantasy, but in reality Samuel Morse had understood the concept of this device early on. The device we've invented is called a repeater, or a relay. A relay is like a sounder in that an incoming current is used to power an electromagnet that pulls down a metal lever. The lever, however, is used as part of a switch connecting a battery to an outgoing wire. In this way, a weak incoming current is "amplified" to make a stronger outgoing current.

Drawn rather schematically, the relay looks like this:

When an incoming current triggers the electromagnet, the electromagnet pulls down a flexible strip of metal that acts like a switch to turn on an outgoing current:

So a telegraph key, a relay, and a sounder are connected more or less like this:

The relay is a remarkable device. It's a switch, surely, but a switch that's turned on and off not by human hands but by a current. You could do amazing things with such devices. You could actually assemble much of a computer with them.

Yes, this relay thing is much too sweet an invention to leave sitting around the telegraphy museum. Let's grab one and stash it inside our jacket and walk quickly past the guards. This relay will come in very handy. But before we can use it, we're going to have to learn to count.