Samuel Morse wasn't the first person to successfully translate the letters of written language to an interpretable code. Nor was he the first person to be remembered more as the name of his code than as himself. That honor must go to a blind French teenager born some 18 years after Samuel Morse but who made his mark much more precociously. Little is known of his life, but what is known makes a compelling story.

Louis Braille was born in 1809 in Coupvray, France, just 25 miles east of Paris. His father was a harness maker. At the age of three—an age when young boys shouldn't be playing in their fathers' workshops—he accidentally stuck a pointed tool in his eye. The wound became infected, and the infection spread to his other eye, leaving him totally blind. Normally he would have been doomed to a life of ignorance and poverty (as most blind people were in those days), but young Louis's intelligence and desire to learn were soon recognized. Through the intervention of the village priest and a schoolteacher, he first attended school in the village with the other children and at the age of 10 was sent to the Royal Institution for Blind Youth in Paris.

One major obstacle in the education of the blind is, of course, their inability to read printed books. Valentin Haüy (1745–1822), the founder of the Paris school, had invented a system of raised letters on paper that could be read by touch. But this system was very difficult to use, and only a few books had been produced using this method.

The sighted Haüy was stuck in a paradigm. To him, an A was an A was an A, and the letter A must look (or feel) like an A. (If given a flashlight to communicate, he might have tried drawing letters in the air as we did before we discovered it didn't work very well.) Haüy probably didn't realize that a type of code quite different from the printed alphabet might be more appropriate for sightless people.

The origins of an alternative type of code came from an unexpected source. Charles Barbier, a captain of the French army, had by 1819 devised a system of writing he called écriture nocturne, or "night writing." This system used a pattern of raised dots and dashes on heavy paper and was intended for use by soldiers in passing notes to each other in the dark when quiet was necessary. The soldiers were able to poke these dots and dashes into the back of the paper using an awl-like stylus. The raised dots could then be read with the fingers.

The problem with Barbier's system is that it was quite complex. Rather than using patterns of dots and dashes that corresponded to letters of the alphabet, Barbier devised patterns that corresponded to sounds, often requiring many codes for a single word. The system worked fine for short messages in the field but was distinctly inadequate for longer texts, let alone entire books.

Louis Braille became familiar with Barbier's system at the age of 12. He liked the use of raised dots, not only because it proved easy to read with the fingers but also because it was easy to write. A student in the classroom equipped with paper and a stylus could actually take notes and read them back. Louis Braille diligently tried to improve the system and within three years (at the age of 15) had come up with his own, the basics of which are still used today. For many years, the system was known only within the school, but it gradually made its way to the rest of the world. In 1835, Louis Braille contracted tuberculosis, which would eventually kill him shortly after his 43rd birthday in 1852.

Today, enhanced versions of the Braille system compete with tape-recorded books for providing the blind with access to the written word, but Braille still remains an invaluable system and the only way to read for people who are both blind and deaf. In recent years, Braille has become more familiar in the public arena as elevators and automatic teller machines are made more accessible to the blind.

What we're going to do in this chapter is dissect Braille code and see how it works. We don't have to actually learn Braille or memorize anything. We just want some insight into the nature of codes.

In Braille, every symbol used in normal written language—specifically, letters, numbers, and punctuation marks—is encoded as one or more raised dots within a two-by-three cell. The dots of the cell are commonly numbered 1 through 6:

In modern-day use, special typewriters or embossers punch the Braille dots into the paper.

Because embossing just a couple pages of this book in Braille would be prohibitively expensive, I've used a notation common for showing Braille on the printed page. In this notation, all six dots in the cell are shown. Large dots indicate the parts of the cell where the paper is raised. Small dots indicate the parts of the cell that are flat. For example, in the Braille character dots 1, 3, and 5 are raised and dots 2, 4, and 6 are not.

What should be interesting to us at this point is that the dots are binary. A particular dot is either flat or raised. That means we can apply what we've learned about Morse code and combinatorial analysis to Braille. We know that there are 6 dots and that each dot can be either flat or raised, so the total number of combinations of 6 flat and raised dots is 2 x 2 x 2 x 2 x 2 x 2, or 26, or 64.

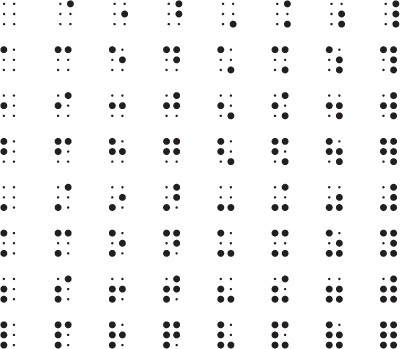

Thus, the system of Braille is capable of representing 64 unique codes. Here they are—all 64 possible Braille codes:

If we find fewer than 64 codes used in Braille, we should question why some of the 64 possible codes aren't being used. If we find more than 64 codes used in Braille, we should question either our sanity or fundamental truths of mathematics, such as 2 plus 2 equaling 4.

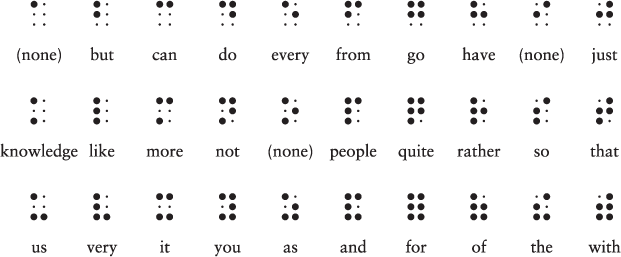

To begin dissecting the code of Braille, let's look at the basic lowercase alphabet:

For example, the phrase "you and me" in Braille looks like this:

Notice that the cells for each letter within a word are separated by a little bit of space; a larger space (essentially a cell with no raised dots) is used between words.

This is the basis of Braille as Louis Braille devised it, or at least as it applies to the letters of the Latin alphabet. Louis Braille also devised codes for letters with accent marks, common in French. Notice that there's no code for w, which isn't used in classical French. (Don't worry. The letter will show up eventually.) At this point, only 25 of the 64 possible codes have been accounted for.

Upon close examination, you'll discover that the three rows of Braille illustrated above show a pattern. The first row (letters a through j) uses only the top four spots in the cell—dots 1, 2, 4, and 5. The second row duplicates the first row except that dot 3 is also raised. The third row is the same except that dots 3 and 6 are raised.

Since the days of Louis Braille, the Braille code has been expanded in various ways. Currently the system used most often in published material in English is called Grade 2 Braille. Grade 2 Braille uses many contractions in order to save trees and to speed reading. For example, if letter codes appear by themselves, they stand for common words. The following three rows (including a "completed" third row) show these word codes:

Thus, the phrase "you and me" can be written in Grade 2 Braille as this:

So far, I've described 31 codes—the no-raised-dots space between words and the 3 rows of 10 codes for letters and words. We're still not close to the 64 codes that are theoretically available. In Grade 2 Braille, as we shall see, nothing is wasted.

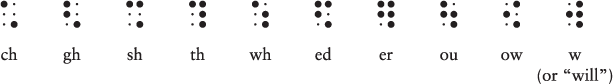

First, we can use the codes for letters a through j combined with a raised dot 6. These are used mostly for contractions of letters within words and also include w and another word abbreviation:

For example, the word "about" can be written in Grade 2 Braille this way:

Second, we can take the codes for letters a through j and "lower" them to use only dots 2, 3, 5, and 6. These codes are used for some punctuation marks and contractions, depending on context:

The first four of these codes are the comma, semicolon, colon, and period. Notice that the same code is used for both left and right parentheses but that two different codes are used for open and closed quotation marks.

We're up to 51 codes so far. The following 6 codes use various unused combinations of dots 3, 4, 5, and 6 to represent contractions and some additional punctuation:

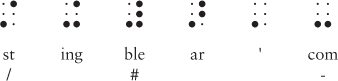

The code for "ble" is very important because when it's not part of a word, it means that the codes that follow should be interpreted as numbers. These number codes are the same as those for letters a through j:

Thus, this sequence of codes means the number 256.

If you've been keeping track, we need 7 more codes to reach the maximum of 64. Here they are:

The first (a raised dot 4) is used as an accent indicator. The others are used as prefixes for some contractions and also for some other purposes: When dots 4 and 6 are raised (the fifth code in this row), the code is a decimal point in numbers or an emphasis indicator, depending on context. When dots 5 and 6 are raised, the code is a letter indicator that counterbalances a number indicator.

And finally (if you've been wondering how Braille encodes capital letters) we have dot 6—the capital indicator. This signals that the letter that follows is uppercase. For example, we can write the name of the original creator of this system as

This is a capital indicator, the letter l, the contraction ou, the letters i and s, a space, another capital indicator, and the letters b, r, a, i, l, l, and e. (In actual use, the name might be abbreviated even more by eliminating the last two letters, which aren't pronounced.)

In summary, we've seen how six binary elements (the dots) yield 64 possible codes and no more. It just so happens that many of these 64 codes perform double duty depending on their context. Of particular interest is the number indicator and the letter indicator that undoes the number indicator. These codes alter the meaning of the codes that follow them—from letters to numbers and from numbers back to letters. Codes such as these are often called precedence, or shift, codes. They alter the meaning of all subsequent codes until the shift is undone.

The capital indicator means that the following letter (and only the following letter) should be uppercase rather than lowercase. A code such as this is known as an escape code. Escape codes let you "escape" from the humdrum, routine interpretation of a sequence of codes and move to a new interpretation. As we'll see in later chapters, shift codes and escape codes are common when written languages are represented by binary codes.