Chapter 6

Price Structure

My new book is coming out soon. It’ll be the usual rubbish, but it won’t cost much. That is the bargain we are going to strike with you.

—JOHN LENNON, BEATLES CHRISTMAS MESSAGE, 1965

Price structures, sometimes called price models, are what translate events into a dollar amount. Structure can also be defined as the terms under which you sell your service or good. A simple “flat” price structure is a transfer of ownership with a specific price tag. Other price structures are more complicated, and can be considered the “formula” by which the transaction will command cash flows. More complex sales may have components of a flat sale price, plus components which are variable with usage (by the unit, by the input, by the event, by the action, etc.)

Sellers regularly ignore their market’s price structure preferences in the name of internal convenience. Frequently we see evidence that some part of the market wants to pay for goods and services in a particular structure, but since that is not how billing systems are set up, marketing plans are constructed or profitability plans are quantified, and the sellers ignore the buyers.

If all the market’s suppliers uniformly ignore a particular pricing preference, little of the harm from poor-fitting price structures is readily apparent in standard corporate market tracking. The market may be smaller than it could be, but that can be hard to prove. Certainly, it does not appear in financial reporting.

If a major supplier breaks ranks or there is a substantial new entrant, however, the market will tend to reward that supplier for providing it what it wants. Our experience has been that often large companies scoff at evidence that a market segment desires a particular price structure, but follows slowly when proof surfaces in the form of lower growth or share loss, buttressing the argument for price structure change.1

Examples of where managers felt confident about their price structure included telephony (until prepaid cards), music (until iTunes), insurance (until GEICO), and publishing (until e-readers.) Examples encompass both consumer and industrial goods.

As a more in-depth example, consider the mobile telephony (cell phone) market. Conventional wisdom for years was that users wanted flat rate plans, and management considered churn and pressures on rates independent of price structure. When AT&T introduced “rollover minutes,” industry pundits derided this as a gimmick, not realizing that it represented a material shift in pricing structure. Rollover minutes effectively converted fixed monthly plans to variable (by-the-minute) plans. All in all, it amounted to a fundamental price change.

To see how this change in terms was fundamental, consider how customer-calling volume, especially among moderate-usage-level subscribers, varies by month. This meant that for many customers, their plans were too small some months and too large other months, as they ran over minute caps or came nowhere near them. Allowing excess minutes as credits for later months countered customer awareness that they were being forced to pay for minutes they would not use in many cases—and paying for unused services is not popular with buyers.

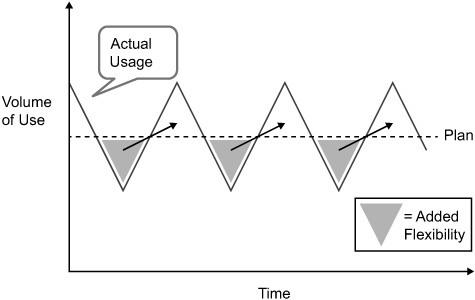

Figure 6-1 illustrates how rollover credits work. Usage in minutes is represented as a fluctuating (jagged) line, and a fixed-minutes pricing plan as a dashed line. Because it appears to preserve minutes during low-usage months and credits those minutes to high-usage months, consumers find that rollover minutes turn a fixed plan into one that accommodates variable usage.

Figure 6-1 Illustration of how “rollover” credits converted a fixed plan to a variable plan.

The benefits of this plan for AT&T were material. Credit Suisse praised the plan in its Great Brands report and attributed a portion of AT&T’s subscriber growth to the plan; other analysts saw the plan as a bulwark against customer outchurn.2 On both counts, it was a price structure innovation that benefited the innovating company.

An industrial example of structure propelling share shift is jet engines. Rolls Royce, behind GE in share, began to sell engines under the “power by the hour” price structure. So, instead of selling a $2 million engine to an airline, and parts and service as needed, the plan sells for example, 100,000 hours of engine operating time, or a number of flights, for a sum of $65 million covering all costs of the engine for those hours.3

This program has proven very successful for Rolls Royce and has been rolled out to several families of engines. Customers have also been enthusiastic about the new structure as it fits their needs better than simple sales. Another example of a market where buyers have chosen the variable output over purchase of a device is solar power—one vendor successfully went from selling solar cells to selling kilowatts.

Price structure must reflect the way in which buyers wish to buy. Market share gains and churn reduction are rewards for being the first company to accommodate market price preferences.

Price Structure Fundamentals

Based on many price studies, we would suggest that few companies are able to impose single price structures on their markets. If supplier plans conflict with market requirements, the market will win in the long run. The most fundamental split of structure is between fixed price (pay the same over time, regardless of volume) and variable pricing (“pay by the drink”). A seller can also offer a combination of the two. When is each structure appropriate?

The rule is that high-volume purchasers often want to buy under a flat price (“all you can eat”); low-volume purchasers often want to buy under variable (“pay by the drink”) plans. Members of each group are cognizant of being either a high- or a low-volume purchaser and so believe that they are likely to pay more or less depending on the structure. For instance, high-volume purchasers appear to believe that they will be denied the benefit of economies of scale if forced to buy under a variable plan. Low-volume purchasers may fear that if lumped together with high-volume purchasers (or users) in a fixed price plan, they will be assigned too high a price relative to their actual consumption.4

So one factor in the market is that price structure must often relate to volume. There is another factor, however: seller profitability. The economic literature shows that where sellers can get a two-part tariff (i.e., charge both on a variable and a fixed basis), they tend to be able to extract higher revenues. This is because the second fixed tariff allows the seller to extract the “gains to trade,” or the triangle in the supply and demand illustrations we all remember from college,5 as shown in Figure 6-2.

Figure 6-2 Gains from adding second tariff: classical economic demonstration of why two price charges can capture more value.

So sellers should be looking for opportunities to sell under a two-part tariff so as to maximize profit. Usually sellers with market power can do so, until that market power fades away:

![]() Before competition, rental car companies charged by the mile (variable) and by the day (fixed). Now they can charge only by the day, and some minor (and changing) set of add-on fees.

Before competition, rental car companies charged by the mile (variable) and by the day (fixed). Now they can charge only by the day, and some minor (and changing) set of add-on fees.

![]() Before hyper-competition, telephone rates were set by distance and time, now they are only flat rate.

Before hyper-competition, telephone rates were set by distance and time, now they are only flat rate.

![]() Before deregulation and competition, banks charged both flat fees (e.g., required balances, yearly fees) and rates linked to volume (wire transfers, amounts borrowed, etc.). Now only one measure is typically applied.

Before deregulation and competition, banks charged both flat fees (e.g., required balances, yearly fees) and rates linked to volume (wire transfers, amounts borrowed, etc.). Now only one measure is typically applied.

So a happy seller is able to impose a two-part charging mechanism. But the seller desire to maximize profit is sometimes counterbalanced by the desire of most buyers to pay as little as possible.

Do buyers care about structure? Often less sophisticated buyers say they care only about the ultimate price level. While that may reflect their conscious point of view, it is not a very savvy buying approach and may not reflect their ultimate behavior.

When buying under a two-part tariff, the ultimate price to be paid is often a mystery. If you’re renting a car for a day at $60 per day, it’s clear you’re going to pay $60. On the other hand, if you’re renting a car for $45 per day and 32 cents per mile, it is less clear what the final bill will look like. This is one reason why cost minimizers will shun two-part tariffs: they have a hard time ensuring cost minimization if they cannot forecast costs. Therefore, cost minimizers favor single-tariff prices because of their clarity and predictability.

Balance your market power against buyer power in setting price structures.

Pulling together these market rules, you can visualize a high-level architecture, or roadmap, of price structure linked to how buyer and sellers interact. Somewhat to our surprise, we have found a remarkable consistency across markets, matching the high-level roadmap. The roadmap is based on the two contextual fundamentals: your competitive strength and the volume of purchase contemplated, as illustrated below in Figure 6-3.

Figure 6-3 Customer price structures: bringing together buyers’ structural preferences and sellers’ structural preferences.

Begin reading the road map, left to right, by assessing the price sensitivity of your customers. If you do not have market power (i.e., buyers will defect to other vendors), you must accede to simple fixed or simple variable pricing. If, on the other hand, you have market power, you should decide on a two-part pricing structure (left side of map).

Then you must consider the purchase volumes of your customers. Are high-volume customers able to buy under a relatively fixed plan? Are small- or low-volume customers able to buy in a variable way? If not, consider offering price plans under which each customer can buy more in the manner he or she wishes. If your company has little market power, offer a pure fixed plan to volume buyers. If your company has substantial power, with volume buyers, have a two-part tariff but bias the split more towards the fixed-price charge.

For instance, echoing the examples earlier, you might license commodity cloud computing software either on a monthly fixed-price plan or a per-use plan. With a little market power, you should be able to add in a sliver of a monthly fee on top of the per-use plan, and some variable fees on top of the fixed-price plan. With more market power, the balanced two-part structures become optimal.

Depending on the diversity of your market, you may be able to sell under one structure (homogenous market), or you may have to offer all four versions of fixed/variable pricing structures (diverse market). Where possible, try to adjust to the buyer’s volume and preferred structure—no benefit comes from needlessly thwarting buyer preferences. If satisfying customers is a concern at your company and you do not offer the indicated roadmap price structure to customers, consider testing a price structure like this in your market.

Where a company has market power, it will impose a two-part charging system. Where it has little power, it can only offer a single-part tariff. The managerial logic behind this is intuitive: where sellers have power, they control price structures; where buyers have power (choice), they eliminate structures with which they do not feel comfortable, in favor of easy price comparison.

Elements of Structure

Now that we have outlined a powerful structural framework, the next question is: just what are the elements that comprise the one or two charging elements? There are literally hundreds of price structure options. However, the main points of departure can be summarized into about eight buckets.

These price structure elements are listed in Figure 6-4. This figure also shows how the different elements are interlinked in the sense that you may need to consider how, for example, chargeback of your costs links to whether you charge on a fixed or variable basis. As another example, tactical structures which draw buyers toward increased purchase quantities can allow for much more aggressive introductory strategies.

Figure 6-4 Structure “daisy”: major categories of price structure and common linkages.

Often companies focus on too few elements of structure. Sometimes discounting and promotion are the sole focus of managers. Smarter companies leverage the entire suite of elements of price. For instance, the chairman of GE recently exhorted his managers to pay more attention to postpurchase economics, such as tax credits and government subsidies for wind power and alternative energy.

The rewards to the right structure are twofold: growth and price level. This should not be a surprise, because pricing is about revenue outcomes, and greater market success and optimal transaction price are two of the most common objectives in pricing.

Changes in the “Unit of Purchase”

The “unit of charging” often has unexploited potential for revenue improvement. Let’s take a close look at a couple of examples of changes in units of purchase and their results.

First example: an online B2B service provider changed its structure from a single per-user price to two prices: “regular” and “lite” user counts. The demarcation between the two was based on the user’s number of hours online. The two levels allowed the provider to capture revenues from occasional users who otherwise would not have been deemed worth their own user ID, and it allowed a somewhat higher price for heavy users who derived a lot more value from the service.

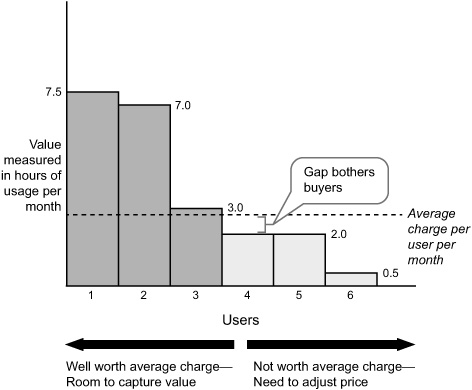

In this example, the context that shaped buyer satisfaction was the internal company comparisons of value and average price per user. When you look at it from an internal customer view, one single user price is often a poor match for some users—with a single price (the average price) per light user that is in excess of the value (in this case, measured by hours of use) obtained from the service. The fact that many heavy users obtained excess value compared with the average price does not fully offset that apparent unfairness—excess value is often not as salient in the overall satisfaction as a shortfall. Whether overall fair or not, the shortfalls between price and value get the attention. This relationship is shown in Figure 6-5.

Figure 6-5 Comparison of value to average charge per user: match of unit to internal perception of cost.

Units of price measure always have implications for how buyers view price but are often taken for granted and left static for long periods. That’s okay when the unit of measure works well for your company, otherwise it’s something to correct. Not surprisingly, it is often the implicit points of comparison, driven by choice of unit, which matter most to buyers.

In the case of the B2B online-service provider, the benefits of moving to two types of pricing units were reduced churn and capturing some new customers from competitors that did not make this price change in unit of purchase. The long-term result of this change in structure was a five-year growth trend with a compund annual growth rate (CAGR) of 38 percent. Price structure was the single most important driver of the provider’s revenue and profit growth over that time period.

Second example: a large industrial specialty chemical company sold its product by the barrel and provided material levels of in-kind support to users, in the forms of containers, technical support, storage, transport, and marketing assistance. Sales were under longer-term contracts based on dollars per barrel. Upon examination, it turned out that one category (segment) of buyer would repeatedly make liberal use of the in-kind support but then fall short on volume estimates. The result was that on a per-barrel basis, net of in-kind support, this segment would underperform price and profit targets.

By separating out the in-kind (fixed) services from the per-barrel (variable) services for the underperforming segment, the provider fixed its pricing problem. Its price negotiations benefited because under the new approach the supplier was relatively indifferent on forecasted volumes described by the buyers. Since the errant segment was easily identified, this practice was soon adopted by most industry participants. The lift in margins was over 4 percent, which is dramatic in that industry.

Adopting price structures suited to your markets can pay material dividends in share and price level.

Price structure helps companies win in the market. But do companies with better price structure always win? No. Better structure is typically measured by the ebbs and flows of market position and comparative discounting.

While better price structure will help a company end up with the largest market share, it does not follow that the best price structure is always associated with the best selling product. Why? Why do we have to measure the trend, not the end result?

This is because, much to our chagrin as pricers, there is more to demand than price structure. Things like product and competition do matter. For instance, most purchasers of downloadable movies and audio books would prefer to own them, with full rights to copy them. However this is not how movies and books have been offered to the market, so this is not a choice for buyers, and so price structure does not play a role—yet. Similarly, until the 1980s, IBM primarily leased computers, despite preferences by many parts of the market to purchase. Demand for IBM computers was still very strong, and IBM was the clear market leader. But once IBM offered a choice between leasing and buying, buying computers quickly prevailed over leasing. It’s the comparison that shows market preference, not absolute volumes.

Market structure preference and results are best measured by relative purchasing patterns and differences in price pressure.

Summary

Structure is the heart of contextual pricing and the formula for long-lived pricing results. Price level changes can give you an instant lift, but such an option is not always open to your company. Price structure improvement is usually an option because many markets are starved for the right structures. Managers looking for a solution to market challenges should always use structure as an improvement lever.

Notes

1. Of course, sometimes the rest of the industry will not follow an innovator’s example. That is fine if the innovation is beneficial to you, but not so good when the innovation attempts to do something unpopular—e.g., attempting to discipline the market. AT&T’s capping of data usage by subscribers so far has not been emulated and has been called a PR disaster. AT&T might have tried a more graduated strategy, beginning with loose bands and eventually letting users grow into them. Abrupt banding called attention to the change and so formed an unfavorable context.

2. Credit Suisse, “Great Brands of Tomorrow,” March 30, 2004. One blogger on the Applease site commented: “The best thing about AT&T is rollover minutes.”

3. “‘Power by the Hour’: Can Paying Only for Performance Redefine How Products Are Sold and Serviced?” See knowledge@ Wharton, February 21, 2007. Other markets where what used to be sold as a product can now be bought as a service include electrical power. “Pay for the Power, Not the Panels,” The New York Times, March 26, 2008, p. H1. Transforming what used to be a product into a service is an expanding phenomenon.

4. Note how the variability in demand for small users, and the consistency of demand for large users, is consistent with this split in preferences. Groups of users/buyers tend to have more predictable demand because the “law of large numbers” means individual fluctuations in usage cancel each other out.

5. Well, some of us. If your memory is foggy, please see the great article by Walter Y. Oi: “A Disneyland Dilemma: Two Part Tariffs for a Mickey Mouse Monopoly,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, vol. 85, February 1971, pp. 77–96.