9 Creative methods for sustainable design for happiness and wellbeing

Emily Corrigan-Kavanagh and Carolina Escobar-Tello

Introduction

Design for happiness and wellbeing is an emerging design approach that has been gaining traction for the past decade. It shifts the view of the user from passive consumer to active participator. It aims to engage users in more sustainable behaviours and interactions within society, the home and the local community, to appeal to their intrinsic values and/or to co-create happy everyday experiences through design and emerging collaboration, rather than the stand-alone physical consumption of objects. Consequently, this approach requires novel ways of prompting and supporting suitable design thinking to trigger relevant design propositions.

Creative methods are useful in encouraging ideation and divergent thinking in design research and practice (Cross, 2008). We define these for the purposes of this discussion as those that require prospective users to create something (e.g., artefacts, enactments) that supports the design process by providing inspiration, information or new understandings about relevant contexts for design ideas – allowing designers, potential users and target groups to collaborate on the development of design projects, such as products, services and systems. However, to date, it is hard to find specific creative methods to design for happiness and wellbeing. This is significant as happiness and wellbeing are notoriously difficult concepts to define (Veenhoven, 2010); their meaning differs for everyone, both culturally and personally, which presents challenges for designing corresponding moments.

Research on the themes of happiness and wellbeing suggests that there are key activities, such as setting goals, that allow individuals to achieve high levels of happiness and wellbeing – adaptable to each person’s preferences, circumstances and cultural context (Seligman, 2002, 2011). Consequently, design artefacts that embed and/or support these actions could potentially present opportunities to improve individuals’ and ultimately society’s happiness and wellbeing. In this chapter, we present the Design for Happiness Framework (DfH) and the Designing for Home Happiness Framework (DfHH) as applicable specific creative methods for this purpose; they provide relevant processes and tools to design for happiness and wellbeing. This chapter presents a short summary of prevalent creative methods available to designers, such as probes, toolkits and prototypes. Following this, the DfH and DfHH are expanded upon, including tools, processes, relevant happiness concepts and how these are embedded in their application and resulting designs. The chapter then concludes with suggestions on how these methods might be implemented in future scenarios and includes guidelines for their use.

Overview of common creative methods for supporting design

The most common creative methods used by designers can be consolidated under the headings: probes, toolkits and prototypes. Notably, Sanders and Stappers (2014) use these categorisations when organising methods for co-designing – those enabling users to contribute ideas to design projects. Other prolific creative design methods can be discussed within these themes, and so they are employed here for discussion purposes. The following is not intended to be a comprehensive review of such, instead relevant aspects for designing for happiness and wellbeing are explored to demonstrate a need to specialise methods in this area.

Probes

The ‘probe’ method usually consists of a well-designed package with various materials and activities for participants to complete unobserved (Mattelmäki, 2006). Using self-documentation, data can be collected from multiple scenarios, as opposed to singular experiences, to create deeper understandings of individuals (DeLongis, Hemphill & Lehman, 1992). A probe can include (daily) logs, maps, cameras and video recorders for participants to express their emotions and experiences. Use of (daily) logs using video and/or photos outside the probe method are referred to as ‘elicitation studies’, where media recorded by participants are used to guide conversations during follow-up interviews (Carter & Mankoff, 2005) – photo elicitation (Harper, 2002) or video elicitation method (Henry & Fetters, 2012), depending on the material produced. Notably, sometimes video or imagery is supplied by the investigator.

Toolkits

Toolkits allow users to volunteer ideas and collaborate with designers on design projects (Sanders & Stappers, 2014). Toolkits can include props, cards, diaries, 3D materials (e.g., Lego, Velcro modelling) and 2D materials (e.g., word and picture sets). Collage-making, concept mapping and acting out scenarios are frequently used as techniques. Toolkits are created by designers and/or researchers with more intentional outcomes than probes (ibid.), tailored to each study’s purpose. They can also include probes to sensitise users to relevant ideas in preparation for toolkit activities. Initial toolkit exercises might be aimed at activating feelings around the subject while later activities could involve visualising new possibilities. Resulting artefacts can then inspire discussion of underlying needs, values and future aspirations, or prompt further research and use of toolkits (ibid.).

Prototypes

Prototypes are artefacts created to evaluate a design proposition with prospective users (Sanders & Stappers, 2012). Generally, prototyping illustrates potential design objects and spaces to validate and refine emerging designs with relevant stakeholders. It could provide an approach for ‘designing for happiness’ by enabling tangible design propositions that can be tested in real-world scenarios with multiple users to develop solutions for collective happiness. Common tools used in prototyping include Lego (Lego Serious Play, 2002), Velcro modelling (Hanington, 2007) and props (Foverskov & Yndigegn, 2011).

Limitations in designing for happiness and wellbeing with probe-related creative methods, toolkits and prototypes

Designing for happiness and wellbeing requires holistic and systemic investigation. Using the methods mentioned, capturing happy experiences and how they relate to society more generally, such as home happiness, either retrospectively (e.g., toolkits) or during moments (e.g., probes) is difficult, as it is hard to motivate participants to complete tasks when deeply immersed in them. For example, a prompting probe activity could disrupt one’s joy when receiving a gift. Additionally, probe results are usually incomplete, uncertain and biased (Gaver et al., 2004), making it difficult to choose relevant content to utilise in designs for happiness and wellbeing. Lastly, deep reflection on the systemic nature of subjective moments (i.e., sustainable happiness), how they are supported personally and communally, is not normally the main focus of toolkits. Creative toolkit activities are generally predefined with prepared materials (i.e., images and words), enabling participants to easily create compositions to support collaborative group work, creating culturally relevant solutions (Sanders & Stappers, 2012).

Relatedly, prototypes can provide stimulus for discussion on illustrated ideas, encourage users to consider other overlapping frames/theories/perspectives and challenge present social trends by illustrating alternative realities (Stappers, 2013). Their creation is therefore vital for ensuring valuable designs for happiness and wellbeing. However, generating appropriate prototypes is not possible without methods that are specific to designing for happiness and wellbeing, given its complexity.

To design for happiness and wellbeing, it is necessary to examine happiness in a collective sense – such as how design can support the happiness of multiple individuals concurrently. This is hard to achieve through individual probe exercises, or with toolkit group visualisation activities when happiness is different for everyone. Instead, specialised activities for introspection on happiness with a facilitator (Corrigan-Doyle, Escobar-Tello & Lo, 2016) and/or using visual stimulus material (e.g., happiness-evoking imagery) with related exercises (Stevens et al., 2013) may prove more suitable. The following sections thus elaborate on unique creative methods specialised for this.

Design for Happiness Framework

The DfH is a progressive design method, including a process and toolkit, that focuses on building sustainable happier societies. When it was first developed, most of the sustainable design methods, tools or approaches focused on the environmental and economic dimension of sustainability (Thorpe, 2012). A few focused on the social dimension of sustainability, but none on happiness and wellbeing.

The unique design process of DfH combines for the first time elements of holistic sustainable design plus happiness characteristics (Escobar-Tello, 2016b). It invites a reinterpretation of the traditional relationship between artefacts and users to a people-centric approach where the characteristics of what is meaningful for people sits at the heart of our material culture (e.g., experiences delivered through products, services and systems that contribute towards happiness and wellbeing). It embodies these key fundamentals to bridge the social gap in design (Escobar-Tello, 2016a), and understands sustainability as a symbiotic system that is continuously updated because of the dynamic conditions of its dimensions. It involves addressing all dimensions (social, economic, environmental and cultural) in a balanced interlocking way, where people are a piece of a collective wider system as opposed to the centre of it; appealing to a timescale that is neither immortalising nor market-driven.

The nature of the DfH is organic, iterative and systemic. However, for the purposes of explaining DfH in a clear manner, the following sections split it into three separate foundations: design approach; design process; and the toolkit. In practice, these have been combined, hence assembling a framework to design for happiness (approach), and they are delivered in an integrated manner (workshop), as illustrated in Figure 9.1 (Escobar-Tello, 2016a).

Figure 9.1 Design for Happiness framework.

Source: Escobar-Tello, 2016.

DfH approach

Within the context of DfH, happiness is understood as ‘a state of deep contentment (serenity and fulfilment) with one’s life which results from the combination of three variables: feeling positive, life satisfaction, and genetics’ (Escobar-Tello, 2016a, p. 95). It is triggered by, and found in, activities that individuals can engage with and that correspond to personal intrinsic values. Furthermore, it holds fantastic potential to drive behaviours towards sustainable lifestyles as its key characteristics overlap with sustainable society’s characteristics (Escobar-Tello & Bhamra, 2009). DfH takes advantage of this and, by using happiness as a leverage, it approaches design in a systemic manner: addressing and changing urgent needs of the world today, uncovering opportunities for innovation, and enabling the design of sustainable artefacts that engage individuals in ‘bigger-than-self’ problems. In this way, its success does not rest only in the tangible characteristics of the framework, namely its design process and toolkit, but also in its capacity to challenge the possible evolution of the design discipline and its (possible) subsequent theoretical development. The approach gives way to bottom-up solutions that deliver a collection of experiences that contribute to the proliferation of happiness, not only because of themselves (i.e., happiness and sustainable society values embedded at the core of the design and the design process of products, services or systems) but also because of the systemic shifts it triggers by encouraging people to behave and live in more sustainable ways (i.e., happiness and sustainable society values embedded at the core of the delivery of products, services or systems).

DfH process

Carried out through a workshop scenario, with the designer as facilitator, DfH brings multidisciplinary stakeholders together to generate design proposals that, via design, contribute to happier and more sustainable societies. It is open to all members of society and can be applied to any challenge.

Through a bespoke design process and toolkit, each DfH workshop session takes participants through six phases of in-depth exploration of a problem to be mitigated. Uncovering its core function or need, this journey opens up a wide canvas for innovative design solutions to emerge at a sustainable product–service system (sustainable PSS) level. Distinctively, the combination of social innovation design methods, service design methods and principles of creativity and sustainability underpin the journey’s guiding narrative (Escobar-Tello, 2016a). This enables participants to really understand the ‘world’ as a co-sustained system. In this way, new thinking is triggered where co-designed solutions are framed in a transformative manner that leads to holistic, sustainable, happier societies. In detail, the journey’s guiding narrative consists of:

- Phase 1. First insight – download, levels understanding of the key foundations of the DfH: ‘happiness’ and ‘sustainable society characteristics’.

- Phase 2. Preparation and incubation – let go, opens up participants’ senses and creativity to contemplate new ways of ‘doing things’, specifically, new holistic, sustainable thinking regarding the problem at hand during the session.

- Phase 3. Incubation part 2 – presence, gives way to new ideas in the shape of draft design concepts that embed happiness and sustainable society characteristics in an innovative manner. The bespoke DfH tools ‘Recording templates’ and ‘Images cards sets’ support this phase.

- Phase 4. Illumination and reflection – let come, focuses on generating design proposals out of the initial concepts in Phase 3. Design proposals evolve and develop into sustainable PSS characterised by their systemic nature; usually including a wide systemic perspective that includes the user’s behaviour, user’s use/experience with the product/service, and their associated contexts of use and routines (e.g., laundry, cooking). The design proposals at this level tend to be service-driven and result in participative experiences in communities that, by their design nature, would trigger happiness. The bespoke DfH ‘Recording templates’ support this phase.

- Phase 5. Illumination and reflection part 2 – co-design and co-creation, brings the generation of design ideas to an end. Participants collate ‘incubating ideas’, developing them into one or two full concepts. The multidisciplinary aspect of the participating group continues to enrich and grounds them within viable contexts of everyday life. The bespoke DfH tools ‘Recording templates’ and ‘Idea catalyst web’ support this phase.

- Phase 6. Evaluation, focuses on assessing the outcomes of the session after it has finished. Particular attention is given to the evaluation of the design proposal/s against the DfH triggers. This phase is led by the session facilitator. The bespoke DfH ‘Range-scale’ tool supports this phase.

DfH toolkit

The inherent nature of happiness, wellbeing and sustainability makes it difficult to understand them, let alone embed them in a holistic manner within new design proposals. Consisting of a set of ‘Recording templates’, ‘Images cards sets’ and ‘Idea catalyst web’, the DfH toolkit aims to facilitate this and successfully achieves this aim by making them tangible, breaking down complex values into simple bites of information. In synthesis:

- The ‘Recording templates’ consist of four sets, each tailored and used in a different workshop phase. They are structured sheets where participants’ thinking, ideas and sketching are recorded. They also provide a useful format to record the workshop outputs.

- The ‘Images cards sets’ consist of nine sets of colour-coded DfH cards, corresponding to the nine triggers of happiness and sustainable lifestyles. They are used to inspire and broaden participants’ creative thinking.

- The ‘Catalyst web puzzle’ helps progress the design ideas into innovative co-designed concepts. It helps to visualise, discuss and reflect on how the ‘happiness’ and ‘sustainable society’ triggers connect to each other and result in a complex, holistic, interactive system.

Making use of synectics, the tools encourage participants to see parallels or connections between apparently dissimilar topics. Overall, they enable and inspire creative dialogues between designers and multidisciplinary stakeholders when exploring new design solutions. Figure 9.2 (Escobar-Tello, 2016a) summarises the five collaborative tools that compose such a toolkit, illustrating the phase and the guiding narrative underlying its deployment within the DfH.

Figure 9.2 Design for Happiness framework, phases and guiding narrative.

Escobar-Tello, 2016.

DfH outputs

The DfH serves to trigger the proliferation of happiness through the design of sustainable PSS, to achieve deep, cultural, systemic shifts and to enable a transition at a broad societal system level. Outputs so far demonstrate that sustainable products, services and systems can enable material changes to take place without having to leave behind social networks that feed our happiness and wellbeing. SLEUTH Project (Escobar-Tello & Bhamra, 2013), for example, is a complex PSS which aims to go beyond saving energy at universities by building on students’ happiness and sustainable lifestyles issues such as ‘communities’, ‘proactive citizenship’, ‘skills development’, ‘sharing PSS’ and ‘low material consumption’. In this way, DfH can assist the development of new processes of designing that enable greater potential for driving sustainable change in business, organisations and society. Its outputs show promise in encouraging a wide array of multidisciplinary practitioners and designers to approach design from a holistic sustainable perspective.

Designing for Home Happiness Framework

The DfHH is a creative method, also following a workshop format, that focuses on enabling the generating of home happiness service designs and/or sustainable PSS. It adheres to the long-term happiness perspective taken by the DfH but also incorporates Seligman’s (2002) ‘authentic happiness’ theory. This concept suggests that long-term happiness consists of three levels, pleasure, engagement and meaning, that tend to occur sequentially in this order. Pleasure (‘The Pleasant Life’) refers to positive emotions, such as joy, most immediately felt from satisfying basic needs (e.g., food) but can also occur from other interactions, such as viewing a beautiful painting for example. Engagement (‘The Good Life’) denotes utilising and/or developing personal strengths. Finally, meaning (‘The Meaningful Life’) results from using these strengths towards the happiness of others, such as helping a charity. Employing this concept allows designs for happiness and wellbeing to be conceived by creating designs that facilitate actions for pleasure, engagement and meaning concurrently. Finally, the DfHH focuses on home because it is very influential in everyone’s happiness, affecting almost all areas of life (e.g., levels of social engagement, security and sleep) (UK Green Building Council, 2016). Relatedly, the ‘essential qualities’ of home can be seen to satisfy basic and psychological needs collectively; for example, the home should provide a space to rest and sleep (basic needs) and to personalise and express love towards family (psychological needs) (Smith, 1994). Furthermore, the home can regulate behaviours by the actions it affords or does not support. Kitchen set-ups with countertops and cooking facilities motivate food preparation, for example, supporting basic needs. Homes can hence be shaped through design to encourage happier and more sustainable lifestyles by supporting alternative activities, such as positive social experiences through the provision of comfortable communal spaces.

DfHH approach

The DfHH takes a workshop approach to create a context in which designers can be sensitised to significant home happiness concepts and come up with appropriate solutions during group work. Designers undertake collective brainstorming to facilitate concept development, enabling a wider discussion of issues and more marketable outcomes. Final outcomes presented and shared between different design groups receive live feedback, fostering further design ideation through the discussion of alternatives or potential modifications to propositions.

DfHH process

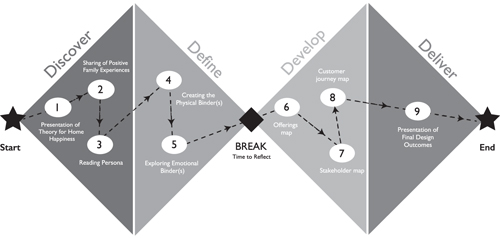

Designing for home happiness requires a process that facilitates empathy, allowing designers to understand users’ home moments by relating these to their own. This is achieved through nine sequential design activities. A summary of these, named by the corresponding task and organised in relation to the Double Diamond Design Process (Design Council, 2005), can be seen in Figure 9.3.

Figure 9.3 Designing for Home Happiness framework, stages and process within the Double Diamond Design Process.

DfHH design tools and techniques

A presentation of home happiness concepts and real-life examples is used to introduce the workshop to provide relatable content for the designers to ‘design for home happiness’. A preparatory exercise (the sharing of positive family experiences) is also employed prior to the workshop where designers are asked to reflect on previous positive home experiences, such as who and what artefacts were involved in making it significant. After the workshop’s introduction, designers are invited to share these. This encourages reflection on significant aspects of positive family experiences before the session, helping designers to make connections between these and those of potential users during the workshop. A persona is then introduced. Personas can support user empathy (Miaskiewicz & Kozar, 2011) by offering an archetype of multiple user characteristics in one or more fictional characters (Marshall et al., 2015), that engage associated memories and encourage greater ideational creativity (So & Joo, 2017). Consequently, the persona is dependent on the target group and should be conceptualised accordingly in relation to each group’s needs and varying scenarios.

Home happiness design tools (HHDTs)

The HHDTs, employed after introducing the persona, are used to facilitate designs encompassing key components of positive family experiences: physical binders and emotional binders. ‘Family’ is used here to reference all cohabiting situations that include close relationships, which can extend to friendships as well as biological relations and intimate partnerships. Physical binders are the object(s) and/or environments that create the right context for activities within positive family experiences as they physically bind individuals to the moment. Emotional binders are those activities that emotionally bind participants to positive family experiences. Design, such as service designs and sustainable PSS, can act as a physical binder for such home moments by facilitating emotional binders that support basic and psychological needs simultaneously. Considering Seligman’s ‘authentic happiness’ theory, it is suggested that unhappy homes are as such because of an overreliance on pleasure activities, such as satisfying basic needs, while those for psychological needs (engagement and meaning) are neglected, as the former cannot be ignored long-term, unlike the latter. Therefore, designs for home happiness need to entice interactions from unhappy homes by advertising the ability to satisfy basic needs and amplify home happiness by fulfilling psychological needs concurrently.

To support this design process, the HHDTs include: Design Tool 1: ‘Creating the physical binders’, consisting of a template, Essential and non-essential home happiness cards (ENHAC) and the Essential and non-essential home activities sheet (ENHAS); and Design Tool 2 ‘Exploring emotional binders’, comprised of a template and three emotional binder sheets (see Figure 9.4).

Figure 9.4 Snapshot of home happiness design tools: Design Tool 1 and Design Tool 2.

Essential home activities are termed as such as they satisfy basic needs, eating for example, which cannot be left unfulfilled long-term. Non-essential home activities refer to those for maintaining psychological needs, such as time with family, and those not necessary for living, which can be neglected for extended periods. The Design Tool 1 template (see top left-hand side of Figure 9.4) prompts users to explore how different essential and non-essential home activities can be combined and collectively facilitated through design, supporting positive family experiences suitable for unhappy homes. The ENHAS (see top middle of Figure 9.4) then provides a graphical illustration of essential and non-essential home action examples that can be considered in this. These are categorised and colour-coded in relation to Maslow’s (1943) Hierarchy of Needs pyramid (see top right-hand side of Figure 9.4) – for example, physiological needs on Maslow’s pyramid and corresponding essential home activities (e.g., cleaning/tidying) are depicted in the same shade. Maslow’s Theory of Motivation states that everyone has universal human needs, the most basic of which, for example food, tend to be pursued before those necessary for psychological wellbeing – love and belonging for example. Organising essential and non-essential home activities in this way allows designers to select home activities from each need grouping (e.g., physiological) to be included in final concepts, improving their potential happiness impact. Homes that are lacking in one need area will be able to benefit from a design proposition that supports home activities for all, or most, needs collectively. The ENHAC supports this process further by illustrating each essential and non-essential home activity individually on cards in the same colour coding as the ENHAS (see bottom left-hand side of Figure 9.4). This enables designers to quickly pair up different combinations of essential and non-essential home activities from each need classification, motivating rapid ideations. The Design Tool 2 template then motivates designers to consider the types of emotional binders (activities within positive family experiences) their emerging concepts support and could facilitate (see bottom right-hand side of Figure 9.4). Design Tool 2 emotional binder sheets then aid this by depicting pictorial and word examples of varying emotional binder categories on either side, such as emotional binders for pleasure, engagement and meaning. The bottom middle of Figure 9.4 displays an example of the image side for the emotional binder sheet for engagement.

These emotional binder types relate specifically to Seligman’s ‘authentic happiness’ theory, as emotional binders (i.e., activities within positive family experiences) can be related directly to the different levels of happiness and be named accordingly. For example, emotional binders for pleasure can include activities for basic needs, providing pleasure; emotional binders for engagement can include developing strengths, supplying engagement; and emotional binders for meaning can involve using one’s strengths for others, supporting meaning. The emotional binder sheets therefore provide visuals and annotations of different activities that can be included in each emotional binder type, allowing designers to understand how their concept could facilitate long-term happiness.

Service design tools

Service design tools are then employed to realise preliminary propositions further, such as an offerings map, stakeholder map and customer journey map. Offerings maps can take many forms. In this case, the offerings map consists of a template comprising three different columns in order to list: (1) existing relatable designs (e.g., services and/or sustainable PSS); (2) their offerings (e.g., limitations and selling points); and (3) those of the home happiness designs in comparison to these. A stakeholder map is employed subsequently to identify the ‘direct’, ‘indirect’ and ‘possible’ stakeholders that could support the design. Its template is kept relatively simple, consisting of three circles that build on top of each other and increase in size, labelled with the previous headings in the same order. A customer journey map is then utilised to understand how future users will interact with designs, incorporating all results from subsequent tools. The customer journey map template illustrates all the generic user steps that can happen with any new design, such as discovery, purchase/join, interaction, continued use and refer. It enables designers to consider and document the practicalities of their home happiness designs: how they are advertised, how and where they are bought or joined, how and why they are interacted with, and why they continue to be used and are recommended to others.

DfHH outputs

So far, design concepts from the DfHH suggest that it could potentially facilitate the creation of sustainable home happiness designs supportive of happiness for various people and homes simultaneously. Emerging propositions all appear to be adjustable to needs and preferences of users because they support generalised activities for essential and non-essential home activities collectively. Examples include a PSS, a ‘Giggleometer’, which gamifies household chores, merging the concepts of essential (e.g., chores) and non-essential home activities (e.g., games); it appears as a physical artefact that is connected to the central smart home system in which timed household tasks can be inputted and their perceived enjoyment recorded, allocating points to different family members upon completion. Activities that can be personalised to each household’s needs and family scores (e.g., from recording feelings and household tasks finished) are accessible through smart devices, such as a mobile app or smart television, encouraging the sharing of emotions, equal delegation of activities and friendly competition.

Discussion

The DfH and DfHH present exciting opportunities for designers, service designers, social innovators and agents of change from any discipline to create propositions for positive systemic transitions that lead to sustainable social initiatives.

The DfH inspires and enables creative dialogues between multiple stakeholders, allowing for the co-design of sustainable PSSs, services and systems for happiness and wellbeing. It is transferable to multiple contexts and situations, including businesses and organisations. Through this, it generates a context for societal transformation through discussions and evolutions of thought as varying groups engage with its toolkit and process.

The DfHH takes a more expert-led perspective, where mixed or focused design teams (e.g., service designers) are assembled to utilise design tools supportive of empathy and designs for home happiness. Design outputs are guided by a persona, personalised to the scenario in question, in order to develop a deep understanding of the most significant needs of related households. The DfHH is therefore context-specific, specialised for designing for the happiness and wellbeing of homes and communities. Consequently, although the DfHH does not directly include co-design methods, these (e.g., toolkits) can be employed to either create the persona or to begin prototyping initial concepts with relevant stakeholders after using the DfHH. In this way, it is anticipated that the DfHH, with continuous refinement and development, will provide a valuable resource for social design studios, think-tanks, councils and community groups to create new and/or improve existing services and sustainable PSSs for home happiness and wellbeing.

Collectively, the DfH and the DfHH appear to be facilitators of social innovations, defined here as solutions to social problems that are initiated, sustained and managed by members of local communities for the wellbeing, happiness and sustainability of specific groups and/or of society more generally. The characteristics of happy societies and those that are sustainable seem to be complementary (Escobar-Tello & Bhamra, 2009), therefore supporting social innovations towards these goals provides a promising route to creating self-maintained happy and sustainable communities. By supporting the development of social innovations, specifically for happiness and more sustainable behaviour, the DfH and DfHH could be used to help build resiliency, independence and sustainable capabilities within different social contexts through design.

In the last ten years the DfH has been used in several academic and non-academic environments, refining its capacities, skills and capabilities. Examples have included projects in and outside the UK, including Colombia and Mexico, confirming its capacity to trigger bottom-up initiatives that proliferate happiness through sustainable PSS. A particularly successful project – in collaboration with Escobar-Tello (2016b) – resulted in four different sustainable PSS solutions that came out of a national initiative to promote healthier nutrition habits in Mexico. These have been historically shaped by the local eating habits and behaviours within the family. Nevertheless, nowadays they are strongly influenced by media (e.g., television, the internet) and ‘globalised’ food choices and lifestyles. Although this is positive in many ways, the lack of knowledge about and time and/or financial resources for healthy diets can affect people’s wellbeing. Consequently, the number of overweight children and adults and lifestyle-related deaths in the population has increased. This project allowed new ways of mitigating this economic and sociocultural issue through design. Design outputs included: (a) a board game for low socioeconomic status families lacking knowledge about healthy eating habits, time to cook healthily and family shared time to teach younger generations about these; (b) a university-led initiative to enable employees to learn, cook and eat healthy lunches; and (c) a student-led initiative to educate and track healthy eating habits while at university. Through the analysis of the empirical evidence it was possible to identify that happiness triggers and sustainable lifestyle characteristics were significant themes that emerged during the project. As in previous case studies, the DfH was welcomed and perceived as a valuable novel approach that enabled the generation of sustainable PSSs.

The DfHH shows promise in facilitating social innovations, either directly through its outputs or the activities they encourage. For example, a previous design resulting from the DfHH included a community-driven organisation. It facilitated the creation and sharing of goods, such as food and crafts, between neighbours by organising exchanges and the supply of information and ideas for related activities to interested households through an online forum, an app and a downloadable information pack. This initiative was intended to act as a mediator for people to understand the true needs of their community as it created a platform (e.g., through sharing goods) for neighbours to communicate other ways in which they could help each other. Evidently, the DfHH presents a potential means of creating future solutions that empower local communities in achieving and maintaining their own happiness and wellbeing. We now end this chapter with some guidelines for best practice for designers when using the DfHH and DfH.

Best practice guidance for designers

Having a predominantly participatory design approach, the DfH requires a cross-disciplinary team to gain maximum benefits from resulting knowledge exchanges and to encourage ‘innovative experiences’. The workshop setting is used to recreate a welcoming and familiar environment where ideas can thrive, the status quo can be challenged and boundaries are blurred. The DfH process, its narrative and toolkit should anchor this environment.

DfH’s nature is flexible, therefore the workshop’s structure – including its narrative and use of the toolkit – can be tailored to meet the aim and the participants’ needs and requirements as needed. For best practice it is recommended to allow a minimum of three hours to complete the workshop, and to use the complete toolkit, enabling a holistic exploration of the triggers and characteristics of happiness and sustainable lifestyles. However, if desired, just one or a selected array of sets of the ‘Images cards’, the most relevant to the brief at hand, could also be used.

Importantly, the toolkit is meant to inspire, surprise and provoke. It is to be used in a playful manner, not too literally, making the strange familiar and vice versa.

The DfHH aims to facilitate designs that are collectively supportive of happiness for various households and the locality. To that end, personas should be created from participatory design activities (e.g., toolkits and/or in-depth interviews) that illustrate connected issues (e.g., lack of security and social relationships) within the home and in the community to direct design outcomes supportive of essential and non-essential home activities simultaneously. Using the ENHAC (Design Tool 1) (see bottom right-hand side of Figure 9.4), designers should aim to develop concepts that support an activity from each need level on the ENHAS (e.g., physiological, security, love, esteem and self-actualisation) (see top middle of Figure 9.4) in order to facilitate long-term home happiness as holistically as possible. Furthermore, this tool, given the multiple card combinations possible, should be explored for at least one hour to maximise its ideational outputs. Finally, the emotional binder sheets (Design Tool 2) (see bottom middle of Figure 9.4) that follow this activity should be treated as prompters to examine how emerging concepts could support home happiness, using insights to select those with the greatest possible benefit to households and their community collectively.

References

- Carter, S., & Mankoff, J. (2005). When participants do the capturing : The role of media in diary studies, CHI. Pittsburgh: Carnegie Mellon University, pp. 899–908.

- Corrigan-Doyle, E., Escobar-Tello, C., & Lo, K.P.Y. (2016). Using art therapy techniques to explore home life happiness. In Happiness: 2nd Global Meeting. Budapest: Interdisciplinary Press, p. in press.

- Cross, N. (2008). Engineering Design Methods: Strategies for Product Design (3rd edition). Chichester, New York, NY, Weinheim, Brisbane, Singapore, Toronto: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

- DeLongis, A., Hemphill, K.J., & Lehman, D.R. (1992). A structured diary methodology for the study of daily events. In Bryant et al. (Eds.), Methodological Issues in Applied Psychology (pp. 83–109). New York, NY: Plenium Press.

- Design Council (2005). The Design Process: What is the Double Diamond? Available from: https://www.designcouncil.org.uk/news-opinion/design-process-what-double-diamond (Accessed 6 December 2017).

- Escobar-Tello, C. (2016a). A design framework to build sustainable societies: Using happiness as leverage. The Design Journal, 19(1), 93–115.

- Escobar-Tello, M.C. (2016b). Design for Happiness and Social Innovation Course. Universidad de Guadalajara, Mexico

- Escobar-Tello, C., & Bhamra, T. (2009). Happiness and its role in sustainable design. In 8th European Academy of Design Conference (pp. 1–5), Aberdeen.

- Escobar-Tello, C., & Bhamra, T. (2013). Happiness as a harmonising path for bringing higher education towards sustainability. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 15(1), 177–197.

- Foverskov, M., & Yndigegn, S.L. (2011). Props to evoke ‘The New’ by staging the everyday into future scenarios. In J. Burr (Ed.), Participatory Innovation Conference (pp. 2208–2214). Sønderborg: University of Southern Denmark. Available from: http://research.kadk.dk/files/34564313/PINC_proceedingsFoveskov2011.pdf

- Gaver, W.W., et al. (2004). Cultural probes and the value of uncertainty. Interactions, XI(5), 53–56.

- Hanington, B.M. (2007). Generative research in design education. In International Association of Societies of Design Research, IASDR 2007 (pp. 1–15), Hong Kong.

- Harper, D. (2002). Talking about pictures: A case for photo elicitation. Visual Studies, 17(1), 13–26.

- Henry, S.G., & Fetters, M.D. (2012). Research method for investigating physician-patient interactions. Annals of Family Medicine, 10(2), 118–126.

- Lego Serious Play (2002). The Science of LEGO ® SERIOUS PLAYTM. Enfield, London. Available from: http://www.strategicplay.ca/upload/documents/the-science-of-lego-serious-play.pdf

- Marshall, R., et al. (2015). Design and evaluation: End users, user datasets and personas. Applied Ergonomics. Elsevier Ltd, 46(Part B), 311–317.

- Maslow, A.H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychology Review, 50, 370–396.

- Mattelmäki, T. (2006). Design Probes. Helsinki: University of Art and Design Helsinki. Available from: https://aaltodoc.aalto.fi:443/handle/123456789/11829

- Miaskiewicz, T., & Kozar, K.A. (2011). Personas and user-centered design: How can personas benefit product design processes? Design Studies. Elsevier Ltd., 32(5), 417–430.

- Sanders, E.B.N., & Stappers, P.J. (2012). Convivial Toolbox: Generative Research for the Front End of Design. London: BIS Publishers.

- Sanders, E.B.N., & Stappers, P.J. (2014). Probes, toolkits and prototypes: Three approaches to making in codesigning. Codesign: International Journal of Cocreation in Design and the Arts. Taylor & Francis, 5–14.

- Seligman, M.E.P. (2002). Authentic Happiness. New York, NY: Atria Paperback.

- Seligman, M.E.P. (2011). Flourish: A New Understanding of Happiness and Well-Being. London and Boston, MA: Nicholas Brealey Publishing.

- Smith, S.G. (1994). The essential qualities of a home. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 14(1), 31–46.

- So, C., & Joo, J. (2017). Does a persona improve creativity? The Design Journal. Routledge, 1–17.

- Stappers, P.J. (2013). Prototypes as central vein for knowledge development. In L. Valentine (Ed.), Prototype: Design and Craft in the 20th Century (pp. 85–98). London: Bloomsbury.

- Stevens, R., Petermans, A., Vanrie, J., & Van Cleempoel, K. (2013). Well-being from the perspective of interior architecture : Expected experience about residing in residential care centers. IASDR13, pp. 26–30.

- Thorpe, A. (2012). Architecture & Design versus Consumerism: How Design Activism Confronts Growth. London: Routledge.

- UK Green Building Council (2016). Health and Wellbeing in Homes. London: UK Green Building Council.

- Veenhoven, R. (2010). How universal is happiness? International Differences in Well-Being, 1–27.