CHAPTER 3

Digital Self-Service Changed Things Forever

What we'll share in this chapter:

- Customer self-service was introduced in the late 1970s, and at first, companies had to work hard to achieve “adoption” of these new technologies.

- Eventually, customers not only got used to the idea of serving themselves but became “hooked” and started demanding more and more.

- Many companies found themselves in a race against ever-increasing customer expectations for greatly improved digital interactions.

- What started as a cost-optimization play became a classic case of “be careful what you wish for.”

THE CITI NEVER SLEEPS

Every digital self-service interaction you've experienced in your lifetime can be traced back to a single event.

Actually, it was two events: The Blizzards of 1978 – a pair of ripsaw Nor'easters that swept up the Atlantic coast that winter – one in January and the other right on its heels in February.

In New York City, facing days of snowbound paralysis with streets blocked off by massive drifts, tens of thousands of people engaged in an activity they had never done before: Getting cash from a machine, instead of from a live teller.

Self-service was born.

The ATM was originally conceived by British inventor John Shepherd-Brown, who (according to legend) was neck-deep in a bubble bath when he came up with a crazy idea: If a vending machine could dispense candy bars, why couldn't we come up with one that spit out cash, instead of 3 Musketeers?

The mechanics of the prototype weren't hard to figure out, but it was only when he joined forces with Scottish engineer James Goodfellow that self-service technology was considered viable. Goodfellow had come up with the missing piece of the puzzle – the Personal Identification Number (PIN) system that allowed electronic banking transactions to become secure.1

Citibank was among the first financial institutions to take the leap and start purchasing automated teller machines, branded as Citicard Banking Centers (CBCs). In late 1977, after conducting user testing and several rounds of market studies, the company spent over $100 million to install ATMs in all five New York boroughs.

To say that the launch went over like a lead balloon would be an insult to the fine people in the lead industry.

Despite the positive response from focus group subjects in sterile research settings, the vast majority of everyday customers couldn't quite warm up to the idea of conducting financial transactions via a vending machine.

For almost two centuries, banking in the United States had always meant going into a branch, filling out a form using the pen-on-a-chain, waiting in a snaking velour-roped line and speaking with a human teller. Giving some newfangled machine complete access to your bank account – without any way of knowing whether it was truly secure – was scary.

And if getting cash out of a Citibank Banking Center wasn't daunting enough, the idea of depositing cash or a check into a robo-teller was out of the question entirely.

But then the blizzards hit. The first one left the city buried under nearly 20 inches of snow, and the second one almost as much. Banks were closed for days, and the only way people could access their money was through the new CBCs.

Usage increased over 20 percent during the first storm, and another 20 percent during the second.2

Word spread fast:

Why wait in a long teller line when you can just walk up and serve yourself? Why be worried about someone looting your account as long as you're the only one who knows your PIN code? It's faster, it's easier, it's just as safe and it puts you in total control over your money – which you can now access any time, any day.

Citibank thus became the first-ever 24/7 financial institution. Their marketing team seized on this singular point of differentiation by creating a tag-line that served them well for years:

The Citi Never Sleeps.3

FROM MIGRATION TO EXPECTATION TO DEMAND

Although it started strictly as a cost-cutting move (“If we could somehow get customers to do basic transactions themselves, imagine how much we could save!”), self-service transformed from something customers were willing to tolerate, to one they began to appreciate, to one they now expect and demand.

If you were to picture a classic “evolution chart,” the self-service version would look like this4:

1970s: Interactive Voice Response

As customer service matured, new innovations followed. One of the earliest breakthroughs was interactive voice response. IVR paved the way for substantial improvements in nonhuman automated service (to repeat this description, please press “4”).

1977: The ATM

Thank you, Mr.'s Shepherd-Brown and Goodfellow, for inventing it!

Early 1980s: Self-Service Gas Stations

Frank Ulrich invented the self-service gas station in 1947. But pay-at-the-pump didn't come along until the mid-1970s, and shortly after that, self-service stations became rule rather than the exception. Except in Oregon and New Jersey, where – to this day – all gas pumps are still operated by attendants.

NOTE: Growing up in Virginia, my son had never been to a full-service gas station in his life and didn't even know there was such a thing. During a road trip when he was about nine years old we stopped in New Jersey for a fill-up. Looking out the window from the back seat, he panicked for a moment, “Dad, what is that man DOING?”

“Don't worry, son, that's what gas stations used to be like in the olden days.”

—RD

1991: Web 1.0

The initial launch of the World Wide Web was based entirely on providing access to static sites that displayed basic information with little interactive capability. But at the time, it was still considered miraculous – like having full access to everything in the Library of Congress while sitting at your kitchen table in a bathrobe!

1992: Self-Service Grocery Checkout Stations

The first grocery store to feature “service robots” (as they were called at the time) was a Price Chopper in Clifton Park, New York. Price check on Robot 3, please.

Mid-1990s: E-commerce Begins

Amazon launched in July 1995 as an online bookstore, but didn't report its first annual profit until 2003. Mr. Bezos's eight-year wait to get into the black seems to have paid off. Ya think?

2004: Web 2.0

Coined by Irish technology visionary Tim O'Reilly at the O'Reilly Media Web Conference in San Francisco, the “re-birth” of the internet was designed around ease of use, democratization of content creation, participatory culture, and interoperability.

It was Web 2.0 that changed everything in self-service. Processes that were once only available offline were now online. Functionality that was once only accessible to agents inside the four walls of a company via back-end systems (ordering, booking, account maintenance) were now – for the first time ever – open and available for use by customers themselves. On their own screens.

Before long, as adoption and utilization of self-service skyrocketed, the screen became the center of the universe for most people. Today, customers are more likely to leave you if you don't let them serve themselves.

From reluctance … to acceptance … to expectation … to demand. The evolution has now reached its final destination.

NEVER GOING BACK AGAIN

Why exactly did self-service start to exert such a powerful hold on customers and their behavior? The answer is based on two considerations – one logical, the other emotional – convenience and agency.

Shep Hyken is considered one of the world's most prolific thought leaders in the customer service space. He is the author of seven books, has performed over 500 keynote addresses at industry and association conferences, and is the recipient of a Lifetime Achievement Award from the National Speakers Association Hall of Fame.

In his book The Convenience Revolution,5 Shep says the ever-increasing public appetite for self-service experiences was inevitable once people got their first taste:

When the airlines first came out with online reservations for simple bookings, the premise was to allow their live phone agents to focus on more complex and profitable interactions. And in order to entice first-timers, many of them offered promotions to customers, saying, “If you book online, we'll give you a bonus” … and from there, most of us would never think of calling to purchase a ticket ever again.

Same thing with online boarding passes. Why would you EVER print out a boarding pass when it's already in your phone? That's not an extra service anymore, it's an expectation – for some customers it feels like it's their right to be able to serve themselves.

Being in control over being able to get what you want, when you want it, the way you want it, is a powerful influence on customer behavior.

And if convenience explains the outsized demand for self-service at a more logical level, it is agency that completes the explanation at a more emotional level.

In their book The Power of Agency,6 Paul Napper and Anthony Rao describe the psychological power of the human need for control:

Agency is what allows you to pause, evaluate, and act when you face a challenge—be it at work, home, or anywhere else in the world. Agency is about being active rather than passive, of reacting effectively to immediate situations and planning effectively for your future. In simpler words, agency is what humans have always used to feel in command of their lives.

Maybe self-service is less about “service” and more about “self.”

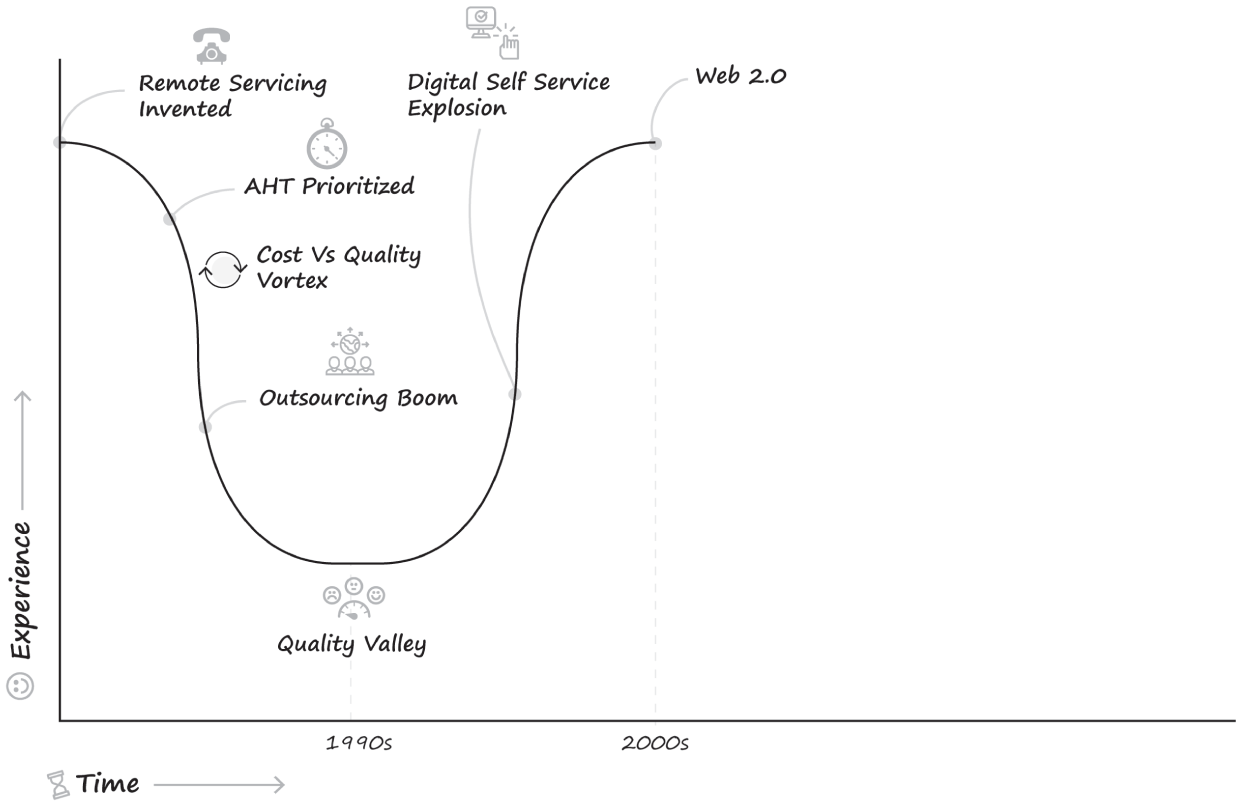

EVOLUTION OF CUSTOMER SERVICE: THE DIGITAL SELF-SERVICE EXPLOSION

Following the Quality Valley of the 1990s, the rising acceptance of digital service and the practical and psychological benefits of self-service (convenience and agency) swung the CX arc back in an upward direction. Many companies started to believe they had found the perfect balance between decreasing the cost of service while increasing the quality of the experience.

But customers would soon come to expect even more and more digital functionality from the companies they chose to do business with, and this rise in expectations would bring with it an unintended consequence.

WHY THE “BOLT-ON” APPROACH DOESN'T CUT IT ANYMORE

As customers came to demand more digital options, and became increasingly comfortable with self-service functionality, it became harder for companies to keep up. The customer service “machine” at most organizations was designed originally for a nondigital world. Many of these newer digital options – most notably email and chat – were layered on top of a company's already-existing phone-based service platform, one at a time, as each became viable.

With some agents doing phone service, some doing chat, others handling email, and so on – the result for many companies became a “multichannel” approach to service, based on a telephony-centric system that wasn't exactly integrated, so much as it was infiltrated.

Justin Robbins describes the evolution of digital service like a sci-fi movie in which the gravitational pull of the past is fighting against the zero-G weightlessness of the future, “In 1999, we had to do one thing well – phones. And then we started to use email. So at first we just had to add one more thing. And if we're being honest, even email wasn't entirely integrated. But then fast-forward to online ordering, through both the website and phone. Then social, SMS, webchat, video. We've seen the need to integrate so many more channels and systems and work streams so that a lot of the stuff that's making them run on the back end was slapped together in a way that wasn't clean or streamlined.”

He adds, “At many companies, customer service started to look like a cardboard box covered in duct tape with a spring poking out one side, and a bungee cord wrapped around it. The cracks were being exposed. The spaceship started shuddering.”

Tethr is an Austin-based company whose proprietary product is an AI-powered “conversation intelligence platform” that measures customer effort without the need for surveys or other customer feedback by processing voice analytics to assess whether a customer is experiencing a high- or low-effort interaction.

Matt Dixon (also a co-author of The Effortless Experience) now serves as Tethr's chief research and innovation officer. He says for many customers, the proliferation of digital channels has led to a new phenomenon: the “Digital Frustration Factor,” which he defines as “how the customer feels about friction they encounter in online channels. It's another form of effort – the obstacles that get in the way of resolution. Tethr data shows customer effort scores are way worse when that person has had a bad digital experience – even worse than a bad phone experience.”

Roger Paulson adds, “A lot of people just expect technology and digital interactions to be magical and perfect. So when they're trying to figure out how to solve a problem and they can't find what they're looking for after 15 minutes, there's no magic. Digital channels aren't perfect – so far at least.”

Compounding this challenge, the timeline for this proliferation of demand for self-service coincided with the first big upsurge in the popularity of social media. It soon became possible for every person's negative experience with any company to be shared in a way that would be visible to everyone.

- The number of easy opportunities for customers to complain about poor service experiences became much higher.

- The threshold for experiences that qualified as “complaint-worthy” became much lower.

SOCIAL MEDIA: SALT IN THE WOUND

Here's a reality we all know to be true – at some point in our society, it became acceptable for people to go online and “rip some company a new one.” Watching a video of someone taking a wild swing at a big corporation, trying to knock the candy out of their multibillion-dollar piñata became a form of FUN!

Fun to do, fun to share with others, fun to witness.

Who remembers an early YouTube viral video titled “United Breaks Guitars?” That example has become so over-referenced that it is generally accepted as the first cell-division of the “We the People vs. The Companies of the World” part of our collective psyche.

Just in case you missed it:

- A musician is on a United Airlines flight from Chicago O'Hare en route to Omaha.

- As he is getting settled into his aisle seat, a window-seat passenger a few rows back is peering outside, saying, “Oh, man, one of those baggage guys just tried to throw a guitar into the cargo bin and missed!”

- The musician fumes during the entire flight knowing his $3,500 guitar was in “checked baggage” because it was too much of a hassle to try to squeeze it into the overhead bin.

- When he finally gets to baggage claim in Omaha – exactly as he already knew before he even opened the case – his pride and joy (a Taylor acoustic) is in pieces.

- He writes a song about it and posts the video online, just as YouTube is getting hot.

- He gets over 20 million views.

- Everyone feels sorry for the dude and laughs at how much United (and “the airlines”) suck.

- Ranting on social media about bad service experiences becomes (and remains) click-bait catnip.

Nate Brown is the co-founder of CX Accelerator – he says every company has to accept the fact that many people now feel they have a social responsibility to “balance the scales” by somehow getting back at a company after a poor service experience. “It became a matter of justice. If we witness wrongdoing, we're gonna lash back out in whatever way we know how – Twitter, negative reviews, telling others. There's a blood debt. I am now actively looking to do damage to their organization. Do I have time to do this? No! But if this experience and that company has created such a debt – it must be paid. And I will find a way.”

That sounds harsh, and rings with a slight tone of overdramatization because most companies report overall customer satisfaction (CSAT) over the past few years has been more than acceptably high. Virtually every company's VoC (voice of customer) data show that most customer interactions are good ones, or at least nominal.

So, how many people are really out there on social media ranting about bad experiences? It's got to be a low number, right? And it is. Another finding from the National Rage Study: 18 percent of consumers who complained about an issue took active steps to increase public awareness of their bad experience.7 One out of five. That's not a bad ratio.

But it's the memorably bad stories that get socialized.

And when you think about what lies ahead in the next few years, consider the percentage of younger people who are becoming more socially active in reporting their negative customer experiences to others. It's certainly higher than 18 percent. A lot higher.

A 2019 report from Adobe showed that among US customers between 18 and 34 years old – 9 in 10 said they will take action after having a bad online customer experience, such as telling friends, stopping purchasing from the company, and posting negative reviews on social media. The data was based on a survey of 1,500 US adults regarding preferences and expectations for digital experiences in the retail, travel & hospitality, media and entertainment, and financial services industries.8

As if the socially ingrained negative psychological bias most people have about customer service wasn't enough of a pothole in the road, the “seamful” interactions customers were having with many of the new digital options fueled further negative experiences, which were exacerbated by viral transmission through social media.

Think of it as a kind of Moore's law – the negativity around customer service doubling every two years.

We Have Transformed into Digital-First Beings

The technology that enables us and the psychology that drives us are both pointed in the same direction – virtually all of us have become digital-first people now. Those who haven't transformed already are getting a little closer every year, or, are just getting on in years.

Therefore, the dynamics of meeting customers where they are and running a customer service operation are very different today. But different doesn't always mean harder. Once you understand the impact of the “peaks and valleys” in this ongoing evolution, then customer service as a function can finally (once and for all) get digital transformation right.

The service executives and leaders who have been the most successful so far and will continue to succeed over the next few years are those who see beyond just operational and economic considerations. They are the ones who are focusing on understanding the underlying psychological principles that drive customer behavior and loyalty – and how that psychology has been changing.

Committing to going all-in on rethinking the way you are providing digital customer service is not only more progressive, it's smart business. A study at MIT found that companies that have embraced digital transformation are 26 percent more profitable than their peers.9

And now the technology required to conduct all service interactions (even those that require a voice interaction) entirely on the customer's screen not only exists, but is already starting to be used successfully – not just by major national or global companies, but even by some smaller regional and local organizations.

As a result, they are dramatically changing the experience of serving their customers – from what was once “a customer service operation that had some digital elements,” to a more evolved form – the name of which became the natural title for this book: Digital Customer Service (DCS).

Their firsthand experiences will be shared in the chapters to follow.

EVOLUTION OF CUSTOMER SERVICE: THE “EXPECTATION VALLEY”

The advent of Web 2.0 represented a high-point for the customer experience as on-screen self-service became an alternative to having to call a company's call center. But expectations rose even more rapidly than most companies could keep up with, thus beginning a channel race. Since each new channel was “bolted-on” to the existing service platform – and none were integrated with phone service – customers and agents weren't “on the same page.”

This mismatch between customer expectations and the reality of “seamful” digital experiences created the disconnect vortex.

Exacerbated by the visibility of poor experiences through social media, the overall reputation of customer service plummeted once more – but this time for different reasons.

In the Expectation Valley, most customers still harbored a negative bias about customer service, but the source of that negativity has evolved. Instead of being frustrated by long hold times, outsourced call centers and agents who tried to rush them off the phone, customers have become increasingly intolerant of the incongruity of multichannel experiences in which none of the various elements of the interaction seemed to be tied together.

KEY TAKEAWAYS: CHAPTER 3

- Digital self-service is now the dominant way people interact with companies. After a slow start, customer acceptance of “serving myself” built momentum over time. Starting with the early introduction of the ATM, self-service exploded with the introduction of Web 2.0. Digital self-service allowed businesses to continue their journey of optimizing for costs but also created a significant increase in customer experience as it quickly resonated with people based on the convenience and agency self-service experiences provide.

- Customers want service experiences to take place on THEIR screen. With the increased demand for digital self-service came higher customer expectations from their on-screen experiences. Businesses scrambled to introduce ways to digitally enhance these experiences, but this was generally done in an incremental (rather than transformative) fashion. The “bolt-on” approach is insufficient to meet the demands of customers who have already transformed.

- Poor service experiences are the ones that feel “seamful” to customers. The nonintegration of digital self-service on my screen with live service on the phone created a mismatch between customer expectations and business realities. The solution: Businesses must meet customers where they are – on their screens. To achieve the goal of customer-centricity and achieve true loyalty, service must transform to become digital-centric rather than phone-centric.

NOTES

- 1. “A History of ATM Innovation,” NCR (January 12, 2021), https://www.ncr.com/blogs/banking/history-atm-innovation (accessed February 21, 2021).

- 2. Anna Gedal, “How a Blizzard Changed Banking.” New York Historical Society (March 21, 2016), https://behindthescenes.nyhistory.org/blizzard-changed-banking/ (accessed February 21, 2021).

- 3. Ibid.

- 4. “The Evolution of Customer Service Technology,” WhosOn, https://www.whoson.com/customer-service/the-evolution-of-customer-service-technology/ (accessed February 21, 2021).

- 5. Shep Hyken, The Convenience Revolution: How to Deliver a Customer Service Experience That Disrupts the Competition and Creates Fierce Loyalty (Shippensburg, PA: Sound Wisdom Publishing, 2018).

- 6. Paul Napper and Anthony Rao, The Power of Agency: The 7 Principles to Conquer Obstacles, Make Effective Decisions, and Create a Life on Your Own Terms (New York: St. Martin's Press, 2019).

- 7. John Goodman, 2020 National Customer Rage Study. Customer Care Measurement & Consulting, 2020. https://www.customercaremc.com/insights/national-customer-rage-study/2020-national-customer-rage-study/

- 8. Nicole Martin, “Why Millenials Have Higher Expectations for Customer Experience than Older Generations,” Forbes (March 26, 2019), https://www.forbes.com/sites/nicolemartin1/2019/03/26/why-millennials-have-higher-expectations-for-customer-experience-than-older-generations (accessed February 12, 2021).

- 9. Jennifer Lund, “How Customer Experience Drives Digital Transformation,” SuperOffice (May 4, 2021), https://www.superoffice.com/blog/digital-transformation/ (accessed March 25, 2021).