Chapter 2 Digital triage forensics and battlefield forensics

In this chapter, we will focus on digital triage forensics (DTF) and how this concept has been developed to what it is today using the computer forensics field triage process model (CFFTPM). We will also discuss the differences between DTF and CFFTPM and define their roles for producing actionable intelligence. You will learn that battlefield forensics is sometimes unorthodox to the everyday investigator who conducts investigations in controlled crime scenes and also the challenges the weapons intelligence team (WIT) members face when exploiting improvised explosive device (IED) scenes on the battlefield. While these teams risk their lives to collect IED evidence, you will read that there is a problem with standardizing the training given to the WITs and other military and civilian entities. How evidence gets to laboratories for processing, what and who make up these labs, and what levels of exploitation are used to finalize the contents of this chapter.

DTF is not a new idea and certainly is not a new investigative thought process. Our growth as a society and the need for a more connected world grow every day. Global businesses and governments are pushing the boundaries of electronic transfer and storage daily. The thirst for quicker, faster communication has also challenged the investigator of today to be able to gather and process information much more rapidly. The investigator needs to stay close behind the criminal enterprises. Yes, behind. The world of investigation is a reactionary one, and typically, the investigator finds himself or herself in the catch-up mode. Very few law enforcement agencies can afford to dedicate an investigator to staying on top of the latest technology. It is usually the investigators’ own desire to learn that keeps them abreast of the new technologies. For example, in 1995, I was an instructor at the Military Police School at Ft McClellan, Alabama, supporting its instructors with a very forward-thinking chain of command. The school’s initial training of computer crime investigation was more an overview of how to use the brand new Microsoft Office programs. Its initial classes were very low tech. However, it only took a year for the school to recognize that future crime investigation would be on the Internet, and the complexity of its training grew quickly. In 2003, the school was on the cutting edge of providing training for computer crime investigation. It was an exception to the rule. In the early days, the Internet did not exist to as far as the average person was concerned. Most people were buying their first home computer not as a necessity but as a luxury. In those days, criminals did not see computers as an enhancement for criminal activities. This is not true today. The criminals, terrorists, and states opposing the United States have recognized and understand the value of technology and Internet as a combat or criminal multiplier. Can you imagine a company or government of any significant size without e-mail or a Web page in today’s world? Whether we like it or not, over the past 13 years, digital media has made its way into every aspect of our lives, and for Americans especially, it has quietly become our most visible Achilles’ heel.

Let us do a little mental exercise. Close your eyes and imagine going a week without using any technology. No Facebook, Myspace, Twitter, Fantasy Football, Voice Over Internet Protocol, etc. Are you done laughing or did your cell phone ring and interrupt you?

In our connected world today, criminals seek the power of free services and tools that come with the Internet. The criminal element has embraced the use of the digital media much more quickly than the law enforcement agencies that have been tasked to enforce the laws, protecting the citizens. These free tools on the Internet open the door for many poorly funded criminal and terrorist enterprises to act and coordinate as a larger, more organized entity. The other enticing draw for the criminal element is that it is possible to attain a certain level of anonymity. An Article written by Rick Ross in 2003 called “Criminal environmental extremists may be recruiting children”1 warned us of the recruiting efforts of organizations on the Internet that target the youth of the Internet. Gangs and terrorist organizations use the Internet routinely to recruit new talent and to spread their ideological causes.

Online Skill

On your computer, bring up your favorite search engine. In the search dialogue box, type in “Gangs Online” and read through some of the pages that are presented to you. Now, type in “Terrorist Organizations Online” and read through the sites that are brought up. Now, go to www.youtube.com and type in “gangs recruiting” and watch a few of the videos that appear. You will see very quickly that the criminal and terrorist organizations have moved to the Internet and have embraced the use of digital media.

Investigators in the battle space do not have the luxury of time as we will discuss later on. Investigators today have a need for actionable intelligence: whether it be the patrol officer at a traffic stop or a battlefield investigator collecting evidence at a postblast investigation (PBI), the need for a quick turnaround of intelligence can be critical. As the criminal element has taken to technology, they, like many of us, do not follow the simple rules to hide or encrypt that data. This then provides the investigator with a unique opportunity. Exploitation of the digital evidence can provide a wealth of actionable intelligence, but the problem is getting to it.

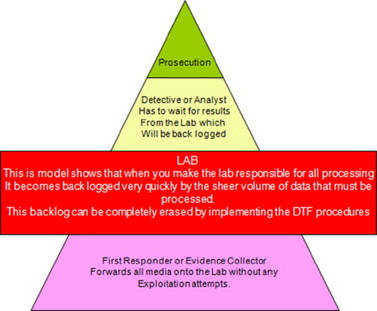

Too often, investigators gather evidence that is not exploited for days or weeks, as it is sent to a central location where the experts can process the media. This removes any possibility of gathering actionable intelligence. The processing model that centralizes the data to one location is antiquated. In the early days of digital media, processing this model was fine. Unfortunately, the load of digital evidence began to overwhelm the labs that were designated to perform the analysis of the electronic media. The current model is shown in Figure 2.1.

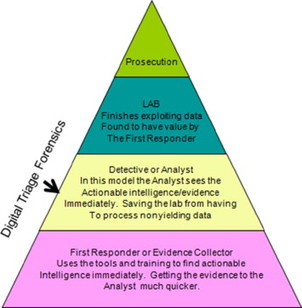

The DTF model alleviates this backlog by implementing a triage forensic step as shown in Figure 2.2.

This backlog of electronic evidence was recognized in the mid-2000s and written about in the paper “Computer Forensics Field Triage Process Model” published in 2006. In this paper, the proposal was made to create a new methodology for processing digital evidence. The investigative process proposed was called the CFFTPM and is defined as those investigative processes that are conducted within the first few hours of an investigation, that provide information used during the suspect interview and search execution phase. Due to the need for information to be obtained in a relatively short time frame, the model usually involves an onsite/field analysis of the computer system(s) in question.

The focus of the model is on the following:

- 1. Find useable evidence immediately;

- 2. Identify victims at acute risk;

- 3. Guide the ongoing investigation;

- 4. Identify potential charges; and

- 5. Accurately assess the offender’s danger to society.

At the same time, it involves protecting the integrity of the evidence and/or potential evidence for further examination and analysis.

Being able to conduct an examination and analysis on scene in a short period and provide investigators with time-sensitive leads and information provide a powerful psychological advantage to the investigative team. Suspects are psychologically more vulnerable within the first few hours of their initial contact with police, especially when this contact occurs in their place of business or dwelling (Yeschke, 2003).2 They tend to be more cooperative and open to answering questions even after being “Mirandized.” This cooperation can be critical in certain cases such as abductions, sexual predatory offenses, etc. What is crucial to the investigator during this initial time period is the knowledge of the full extent of the crime and/or involvement of the suspect and “triggers” that further increase the suspect’s willingness to talk and cooperate. These triggers may be found in the digital evidence located on the suspect’s system(s) (e.g., e-mail correspondence, digital maps, pictures, chat logs, etc.).

The CFFTPM uses phases derived from the integrated digital investigation process (IDIP) model of Carrier and Spafford (2003)3 and the digital crime scene analysis (DCSA) model developed by Rogers et al.4 The phases include planning, triage, usage/user profiles, chronology/timeline, Internet activity, and case-specific evidence. These six phases constitute a high level of categorization and each phase has several subtasks and considerations, which the Conference on Digital Forensics, Security and Law, 2006, classifies according to the specifics of the case, file system, operating system under investigation, etc.

The use of higher order categories allows the process model to be generalized across various types of investigations that deal with digital evidence. The need for a general model has been identified in several studies as a core component of a practical/pragmatic approach for law enforcement investigations (ISTS, 2004;5 Rogers and Seigfried, 2004;6 Stambaugh et al., 20017). Before discussing each of the model’s phases, it is important that qualifications be placed around the use of the CFFTPM, as the model is not appropriate for all investigative situations.

This CFFTPM model was the starting point that I used for the creation of the DTF model. The CFFTPM model does not take into consideration the challenges posed by the battlefield crime scene. Table 2.1 summarizes the differences.

Table 2.1 Comparison Table of All the Models

| Traditional | CFFTPM | DTF | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Planning | Planning | Planning | |||

| Identification | Triage | Identification | |||

| Collection | Identification | Collection | |||

| Preservation | Collection | Preservation | |||

| Examination | Preservation | Triage | |||

| Analysis | Examination | Examination | |||

| Report | Analysis | Analysis | |||

| Report | Report | ||||

All the models start out the same with the planning stage, which is critically important to successful operations. In the traditional and DTF models, the identification, collection, and preservation are done at the scene; in the CFFTPM model, the triage element is added, allowing the investigator to be able to perform some limited triage examinations at the scene. The CFFTPM model allows the investigator to be trained to gather and exploit data at the scene immediately. This triage process is a great improvement over the normal model, as the investigator is given the opportunity to gather immediate intelligence. The triage also allows the investigator to prioritize the evidence that he/she may send to the lab to aid it in not having to process junk data.

So, how is the DTF model different from the CFFTPM model? In the DTF model, the triage processing is not done at the scene; instead, it is done at the Forward Operating Base (FOB). Why was this necessary to move the triage step? The answer is simply safety and time. The triage processing was moved after watching the work-flow process of the investigator in a battlefield environment. To fully understand how the workflow of the battlefield investigator affects the placement of the triage process, we should fully define the DTF model.

DTF is defined as the process of identifying electronic evidence containers that can yield actionable intelligence for the battlefield commander while maintaining the integrity and pristine nature of evidence. Actionable intelligence is obviously the difference in the model. We defined actionable intelligence earlier as intelligence that can be acted upon within a 12–72 hour period. An example of using actionable intelligence with this model in a combat theater might be when a patrol moving down a supply route encounters a possible insurgent. The patrol, after detaining the individual, discovers a cell phone. The cell phone is sent back to the FOB and quickly analyzed by the team investigator. A review of the noninterpretable data from the cell phone reveals pictures of an intersection within close proximity to where the individual was detained. The pictures reveal photos showing wires protruding from the ground. The investigator immediately realizes that this individual has pictures of an IED. The investigator looks at the timestamp of the pictures and notes that the pictures were taken just 2 hour ago. No significant activity has occurred in that intersection in the last 5 hour. The patrol alerts an Explosive Ordinance Disposal (EOD) team that is dispatched to the scene. The EOD team successfully disarms the IED, preventing a serious event from occurring. In this instance, the actionable intelligence gathered from the cell phone was able to create a preblast event instead of a postblast event where soldiers may have been injured or killed.

In the preceding example, we can see why we move the triage to after the scene collection. The proper triage of the evidence must occur quickly in all situations. As was stated earlier, the two defining differences from the CFFTPM model and the DTF model are safety and time.

- Safety for a combat investigator is the amount of exposure he/she must place himself/herself in to be able to gather evidence from the battlefield crime scene. While the investigator is exposed, he/she risks sniper attacks, indirect or direct fire, secondary IED, or mortar attacks.

- Time is defined as the time that an investigator has to conduct the battlefield investigation. Typically, the investigator will have from 10 to 60 min to collect and process the battlefield crime scene. This includes the collection of the digital evidence. Imagine telling a stateside investigator that he/she has 60 min to process and investigate a car bomb in a mall parking lot!

Battlefield forensics versus controlled crime environments

The battlefield crime scenes in Iraq brought these two new conditions clearly into focus. By no means does this suggest that the investigator is doing a poor job; however, the investigator must work more diligently to prioritize the evidence and move more quickly and proficiently. To their credit, the WITs in Iraq have become very proficient at conducting these types of investigations. In this situation triaging the evidence at the scene is just not practical.

So, do these new models alleviate the need for traditional forensic models and the further processing of the evidence by the lab? No, they absolutely do not do so. The CFFTPM and DTF models are not designed to do a complete review of the data containers. In the DTF model, specifically only those data containers that may reveal noninterpretive evidence such as pictures and video are reviewed completely unless an interpreter is available: then, maybe textual data will be reviewed. The triage process does not typically look for unallocated data storage or encrypted data. The triage analysis is looking to identify those containers producing actionable intelligence and to prioritize the digital device when it goes to the lab to assist in making the full analysis more effecient. For the DTF process to work, the investigator must employ a collection method or procedure that is fast and effective in all situations.

Today’s civilian investigators cannot even imagine what it would be like to collect evidence within the battlefield. Here, in the United States, investigators have as much time as needed to investigate their scenes as well as collect evidence in a controlled environment. Civilian investigators do not have to worry about secondary IEDs that may go off while on the scene. They do not have to worry about being attacked or shot at by snipers, and they do not have to wear body armor and carry a combat load of ammunition and weapons while trying to conduct their evidence-collection efforts.

WIT members have to learn to quickly assess their scene, prioritize in their mind what items of evidence are most crucial to collect, photograph the scene and surrounding area, and grab and bag the evidence, sometimes in as little as 5 min. To the civilian investigator, this would be mind boggling and he/she might ask how the WIT can be effective in its evidence-collection efforts. Through the WIT members’ training, seasoned law enforcement professionals guide them in sound evidence-collection methods that are geared to collect the best possible pieces of evidence in the quickest manner that still maintains the integrity of the evidence so that it can be properly exploited and used in a criminal court. Are pieces of evidence missed or contaminated during these hurried collection efforts? Sure, but considering the exigency of the situations WIT members face in their environment, the “good” evidence they do collect is used in Iraqi courts to successfully convict those IED makers who have killed or tried to kill U.S. forces and Iraqi civilians.

Consolidated discipline training

One of the issues in making the DTF model work is consolidation of training. There are many contract companies teaching the force today, and standardization of training is an ongoing problem. This would appear to be common sense, but in reality it is not widely practiced. In our experience with other contractors, we often find that companies are afraid of losing their intellectual property, and this prevents a fluid exchange of ideas. At times, this is a well-founded fear but one that must be overcome.

The success of any training program relies on a uniform training doctrine. One very successful approach to the training model is in the cluster strategy employed by the National Forensic Science Technology Center (NFSTC) in Largo, Florida. This innovative approach to training was the brainchild of Kevin Lothridge, the chief executive officer (CEO) at NFSTC. By working closely together with several companies, such as the High Tech Crime Institute, Inc., Ron Smith and Associates, Forensic Technologies, and other organizations with completely different skill sets, training options are widely expanded. These organizations keep but one goal in mind—to provide the absolute best training to clients. To that end, they work under teaming agreements to provide a wide variety of training specialties in an efficient environment. By combining the efforts of multiple specialists into a uniform model, this approach creates a training selection that offers the full view of battlefield scene collection and processing.

Participating in a cluster of complementary organizations requires intercompany exchange of training materials to ensure that everyone is teaching with a single voice and that no one will be trained with a different procedure no matter what class they are in. This one simple requirement has had a tremendous effect on the curriculum being offered. Other policies and procedures ensure that the student gets the highest level of effective training possible.

The second part to the success of the innovation center is the extensive investment that has been made in the infrastructure of the center. The student literally has a hands-on experience from day 1. Scenario sites at the center provide a real-world look and feel to what the student may encounter when at a battlefield scene.

The innovations center is going to be a model that many other centers are going to try and emulate in the future. Visit NFSTC at http://www.nfstc.org/training/state-of-the-art-training-lab/

How does evidence go from the battlefield to the lab?

As WITs collect evidence from IED scenes and caches, they warehouse it at their FOB in the most secure fashion available to them, maintaining a chain of custody. Once they have collected, processed, and exploited their evidence to the best of their abilities, the evidence is packaged and shipped to the Combined Explosives Exploitation Cell (CEXC) at Camp Victory in Baghdad. In the early days of WITs, team members used to hand-carry all evidence to CEXC via helicopter or convoy. Nowadays, WITs can package the evidence, sign over the chain of custody to the helicopter commander or the convoy commander, and, once the evidence arrives at Camp Victory, a member of the CEXC can sign for it and take the evidence to their lab.

The CEXC supports the operational units by conducting further exploitation of evidence in a state-of-the-art lab and controlled environment. Members of the lab are experts in their fields from federal agencies such as the Federal Bureau of Investigations (FBI); the Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives (ATFE); the EOD; and the Joint IED Defeat Organization (JIEDDO), to name a few, as well as lab technicians from all over the world.

The CEXC conducts investigations of significant events, updates electronic warfare frequencies, tests explosive residues, and identifies IED trends and bomb maker signatures. Methods used in their exploitation of evidence consist of triaging the evidence to determine the priority of processing the evidence, photography, technical exploitation, forensic exploitation, and biometric exploitation.

The Joint Expeditionary Forensic Facility (JEFF) is another lab where evidence can be sent for studying machinery and tool markings on IED evidence. This is especially important when explosively formed projectile (EFP) liners are discovered, as the lab technicians may be able to determine where the EFP was made and collect data as to how it was made. The JEFFs primarily exploit non-IED evidence such as firearms and they conduct tool mark analysis as well.

The Terrorist Explosive Device Analytical Center (TEDAC) is a lab ran by the FBI at Quantico, Virginia. The TEDAC’s mission is to manage exploitation of IEDs of interest to the U.S. Government and is the warehouse for IED evidence. TEDAC also coordinates with other government agencies to further exploit and research IED materials and components.

Five levels of exploitation of WTI materials

The above-mentioned labs all have their roles in exploiting IED evidence, but there are five levels of exploitation that you need to be aware of. Each level has its own unique mission and exploitation requirements that ultimately support the battlefield commanders. These commanders require feedback from exploitation efforts at all levels to remain offensive in their Area of Operations (AORs). The five levels of exploitation are the following:

- Level 1: Tactical

- Level 2: Operational

- Level 3: Strategic

- Level 4: National

- Level 5: Special Activities

An explanation of the five levels of exploitation as they relate to IED evidence follows. Level 1 exploitation involves collection of evidence at IED pre/post blast scenes and caches by WIT members and maneuver units in the field. This is the most basic and important collection level, as, without the evidence, no analysis or actionable intelligence could be obtained. WIT members are trained in Level 1 exploitation so they can garner any actionable intelligence from their evidence and report it within a 72-hour time frame. This is especially crucial when digital media are present. WIT members can image hard disk drives with Parabens Forensic Replicator and use triage forensic tools such as Parabens P2 Commander to conduct analysis of the hard disk drives. Cell phones can be analyzed with Parabens Device Seizure tool. There are other triage forensic tools available for use in the marketplace; however, WITs are supplied with Parabens products at this time.

Level 2 exploitation is conducted by the forensic labs in theaters such as CEXC and JEFF. Both labs use many evidence exploitation methods that are very sophisticated and specialized. This level of exploitation is typically conducted in theater, so information gleaned from Level 2 exploitation can be used to immediately support the battlefield commanders.

Level 3 exploitation involves scientific examination and analysis of IED evidence and provides direct support to the attacking the enemy’s network.

Level 4 exploitation is managed by the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA). This level of exploitation combines collection, exploitation, and analysis with national policy and requests assistance from other national labs such as within the Department of Justice and the Department of Energy.

Level 5 Exploitation is collection, analysis, and research by government agencies and private research firms that focus on developing methods to enhance collection efforts in the field.

The benefit of using the DTF model is clear in the battlefield or combat situation. Current processing models are designed to be used in traditional investigative environments and do not take into consideration safety and time that must be evaluated when in a hostile environment. The benefits of the DTF process are the following:

- It returns actionable intelligence in a speedy reliable manner.

- It identifies devices that require further analysis by a true digital forensic lab.

- It permits timely coordinated processing that allows the investigator a minimal amount of time at the crime scene or objective.

It is important to remember that training without proper policy implementation will result in the failure of the DTF model. Training must also be uniform across the board, providing for a one-voice training effect. This can only be accomplished when contractors feel that they are a part of a team and that their intellectual property is going to be protected.

Controlled crime scenes cannot even compare to crime scenes on the battlefield, yet WIT members successfully conduct evidence collection that leads to prosecution of bomb makers and emplacers using sound battlefield evidence collection methods developed over the years.

Without the many layers and levels of exploitation and the laboratories that support the efforts of the evidence collectors, no progress would be made against our enemies as we take the fight back to them by analyzing and exploiting battlefield evidence to create new Tactical Training Plans (TTPs) for our battlefield commanders to use.

In the next few chapters, we are going to show the DTF model employed at the combat theater level. We will cover traditional storage containers such as laptops and thumb drives, etc., moving into the more complex processing of cellular devices. The programs and procedures that we will be using to illustrate the DTF process are currently being used in Iraq and Afghanistan to perform the DTF process.

1 Ross R. Criminal environmental extremists may be recruiting children. Posted in Environmental Extremists, Animal Rights and Environmental Extremists at 6:03 p.m. by Rick Ross. www.cultnews.com/?p=1404 2003

2 Yeschke C. The art of investigative interviewing –second edition 2003. Butterworth Heineman. Boston

3 Carrier B., Spafford E.. Getting Physical with the Digital Investigation Process. International Journal of Digital Evidence. 2003;2(2):20.

4 Rogers M., Goldman J., Mislan R., Wedge T., Debrota S. Computer forensics field triage process model, Paper presented at the Conference on Digital Forensics, Security and Law 2006. www.digitalforensics-conference.org/CFFTPM/CDFSL-proceedings2006-CFFTPM.pdf

5 Institute for Security Technology Studies Law enforcement tools and technologies for investigating cyber attacks: A national research and development agenda. Retrieved September 9, 2004 from http://www.ists.dartmouth.edu

6 Rogers M, Seigfried K. The future of computer forensics: A needs analysis survey. Computers and Security (Spring 2004)

7 Stambaugh H., Beaupre D., Icove D., Baker R., Cassaday W., Williams W. Electronic crime needs assessment for state and local law enforcement. Retrieved September 1, 2005 from http://www.ojp.usdoj.gov/nij/pubs-sum/186276.htm 2001