7

Very Precious Memories: Digital Memories and Data Valorization

“We have more ‘old’ photos and content than ever before, yet most of the Internet focuses on the ‘new’”1. By introducing its application in this way, Timehop company disseminates something that was previously lacking and Internet users can organize and promote the ever-increasing mass of content of a dynamic. First, there is a lack of tools made available to Internet users to organize and value the ever-increasing mass of archived content. Second, there is a dynamic that claims to respond to this lack and of which Timehop would like to be the precursor: that of the development by the digital industry of a large number of tools to meet a need that it has largely contributed to producing.

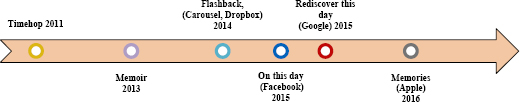

This contribution is part of my doctoral research work in which I questioned how these “digital memories” reflect a certain conception of individual memory and the role that the digitalization of user history plays in an environment often described as the present and the “instantaneous”. In recent years, however, we have seen an increase in the number of applications and functionalities that allow users to centralize, sort and organize their data in order to suggest the creation of “digital memories” (Figure 7.1). As early as 2010, Foursquare introduced the connection history of its users and Momento, a “smart diary”, but it was Timehop which, in 2011, popularized the principle of algorithmic suggestion of old content in the form of memories. Every day, the application offers its users the opportunity to rediscover content produced or published on the same day in previous years. In 2013, Memoir adopted this feature, completing an ambitious project of suggestions for sharing memories according to a place, a person associated with certain content or even annotations and indexing of content. Nevertheless, Memoir closed in 2017.

Figure 7.1. Timeline of the launch of the main applications and features for suggesting digital memories

This principle has been adopted by major players in the digital economy. At the end of 2014, Carousel (Dropbox’s photo application) included “Flashback”, its memory suggestion feature. Facebook’s launch of “On This Day” in 2015 was part of a series of features and changes to the interface, producing a temporal ordering of digital identities. Among these, as early as 2010, there was the “Photo memories” sidebar, followed in 2012 by the Timeline and the “Life Events”, which began the digitalization of the biographical elements preceding the very existence of the network. More recently, in 2018, the “Memories” sidebar was unveiled, bringing together most of the content (re)produced by these different features. For its part, in 2015 Google Photos proposed “Rediscover This Day” and, in 2016, Apple introduced its “Memories” feature.

There are of course different explanatory factors that can explain the adoption of these mechanisms of digital memory suggestion. While the strength of the conventions (Alloing and Pierre 2017) and the personalizing effect2 have probably had an important role in the development of these functionalities, it is above all the economic stake relating to the control of data flows that interests me here. Indeed, the decompartmentalization and access to pre-used data by platforms3 such as Facebook or Google by new players (applications such as Timehop and Memoir) are key issues to which all stakeholders have had to respond. By choosing to direct my investigation towards the practices of the actors who produce and promote these tools, it is a question of reporting on how their positions partly determine their conceptions of “digital memories” and, consequently, of memory. Among the determinations that work on the practices of the actors, economic stakes are of course at the forefront and therefore play a significant role in our daily practices of reminiscence: there is a majority view of memory and the value of memories that is played out in the economic competition that opposes, for example, Google to Facebook. It is also all the more legitimate to question the economic value of digital memories as the resurgence of old content relaunches the competition for the appropriation of user data. Indeed, the production of “digital memories”, and especially their algorithmic suggestion, involves a new circulation of data that has remained “dormant”4. These are therefore likely to escape the company that owns them. If we agree with the idea that “value comes not so much from data as from their circulation and combination in algorithms and mediation processes” (Henri 2018, p. 80), questioning the “path” that these digital memories take is particularly revealing of the economic stakes that mobilize the different actors involved. Therefore, in support of the interviews conducted in the United States with the employees of Timehop, Memoir, Facebook and Google Photos, I inquired about the types of channels used by the suggested content. These flows differ according to the companies that convert archived content into memories, which means that these data use different channels and this invites us to consider the various economic issues they respond to. In other words, it means asking where the content converted into memory comes from, where it goes according to the actors who grasp it and how they will, according to their divergent interests, try to influence these flows.

In this chapter, I will briefly report on the emergence of “digital memories” and the actors who produce them (section 7.1). This inventory is essential to understand how the trajectories initiated by the start-ups behind these tools (section 7.2) have generated a response from dominant players in the digital economy, consisting of limiting these trajectories to an internal circulation (section 7.3).

7.1. The high dependency of start-ups

Start-ups that create applications that offer memory suggestions are highly dependent on dominant platforms. This obvious dependence was expressed several times during my investigation. An employee occupying a high position in the hierarchy of one of these start-ups explained to me that its growth “depends on the other networks”. This dependence is mainly expressed in terms of content circulation, as these applications operate partly on content from “outside” (from platforms such as Facebook, Google and Dropbox) and, once converted into memories, enhance their distribution by or on these platforms (Facebook wall, Twitter, Google+, Gmail, etc.).

7.1.1. Capturing dormant content

Indeed, in order to work, these applications require a significant amount of data that can be regularly converted into memories: “Basically everything that your memory does, we can do if we have enough data being captured”, Memoir director Lee Hoffman told the press (quoted in Fiegerman 2013). The volume of data needed to suggest memories is indeed an aspect highlighted by a large number of actors I have met. Only if the application has allowed access to a large volume of data can it fulfill the promise made to the user to provide him/her with his/her regular stream of memories. However, a large part of this data is held by dominant players in the digital economy (Fabernovel, cited in Casado and Miguel 2016), who act as intermediaries between advertisers and users5. It is therefore with regard to data collection that this dependence of start-ups on these dominant actors is first established.

This dependence is also based on the acquisition of users that enables platforms to dominate. Indeed, one of the keys to the success of an application, according to the several stakeholders interviewed, consists of the rapid growth in the number of users, which makes it possible to engage with public revenues as soon as possible. The difficulties encountered following the reduction in the scope of “pages” on Facebook6 reflect the role that Facebook played in the visibility and acquisition of the users of these applications. Timehop and Memoir have therefore developed alternative strategies to win new users. Developing application-specific communication systems was one of these strategies. Hence, in 2014, Timehop proposed a system of sharing by email or SMS which, thanks to a widget, allowed the recipient to see the shared memory, accompanied by the company logo. Memoir also offered exchanges by email and internally through the application itself.

A true social network of memories, Memoir encouraged sharing by informing its users of the memories of their friends that might interest them. Developing “new forms of sociability based on the logic of monitoring” (Merzeau 2009, p. 76) was a strong response for the company to the obstacles posed by the dominant players in the digital economy.

7.1.2. Confirming their value

Each of these applications offers a simplified way to share content on digital social networks. Content originally published by a user on Facebook, once converted into a memory by Timehop, can be republished on Facebook. The trajectory of content is therefore not one-way (from a dominant platform to the application), but circular (from a dominant platform to the application, then to one of these platforms), because the return in the form of memory of the initial content on a platform, from which it is often derived, is a guarantee of value. It is indeed an important signal in terms of quality: “the strongest metric [of the quality of the suggested memory] is when they share it again”, explained a manager of one of these applications. The dominant platforms are therefore spaces where the value of these memories is negotiated and confirmed.

The publication of a memory in these spaces is also part of the company’s growth strategy. A user sharing a memory there offers an opportunity to acquire new users (personal pages that have, for example, a different scope from corporate pages on Facebook). Start-ups’ dependence on dominant players is therefore established both in terms of access to content and in terms of the visibility of their production. The trajectory that these contents processed by the applications follow is, therefore, circular and exogenous, with start-ups – and Timehop in particular, which does not offer any “social” function or profile page accessible to the user where memories could be saved – acting as “conversion” tools (converting various content into memories) that have not necessarily been produced to stay there.

Although they benefit from the activity and exchanges generated by applications, it is, therefore, the dominant platforms and their policies towards other stakeholders in their business ecosystems that determine attack strategies for application growth and monetization.

7.2. Tagging traffic: the response of dominant platforms

7.2.1. Limiting external traffic

This dependence on applications has resulted in a frontal difficulty: from 2014, the dominant platforms have produced similar functionalities, limiting the circulation of their data to the outside and thus avoiding their possible leakage to other important platforms. Indeed, Facebook content suggested as a memory by Timehop can for example be easily published on Twitter or shared by Gmail. Start-up actors seem to have experienced these limitations as barriers imposed by multinationals, with which they had sometimes been able to maintain collaborative relationships while contributing to their development. The development of such functionalities by players such as Facebook or Google has had the dual effect of strengthening their activities while limiting competition from applications seeking to monetize this data through the sale of advertising space.

This limitation of data flow to applications has proven to be very effective: Timehop, which had reached 6 million daily users at the end of 2014, had about 38% fewer downloads in the United States one year after the arrival of “On this day” which, during the same period, had reached 60 million daily users (Lunden 2017). There is no need, moreover, to offer similar services in their entirety. Benefiting from what Alloing and Pierre (2017) call “cognitive impregnation” (p. 38), and considering that this type of service was already known to a large number of users, these dominant platforms were able to settle for less-complete products that were sufficient to make the applications that were developed by independent companies (start-ups) less attractive. One respondent testified to this point, explaining that Facebook’s launch of “On this day”, although based on a limited amount of user information, had stopped the growth of her own application.

These dominant actors will in turn try to strengthen exchanges within their platform (Hutchinson 2017). However, these shares take different forms and the development of memory suggestion features seems above all to reflect the competition between the dominant players in the digital economy. Regarding Google Photos, where the sharing function is presented as one of the essential pillars of the service, the focus is on the different types of content: sharing a photo, an album or the entire library, or automatically sharing content filtered according to places, dates, faces, etc. Following the failure of Google+, it is a question of the company competing with Facebook in the field of digital social networks and, more particularly, in the field of content sharing. To achieve this, Google Photos intends to distinguish itself by the mode of relationships to which the proposed shares respond. Indeed, the actors of Google Photos are pleased to value relationships of proximity, with people “truly” close to themselves, suggesting the fictitious nature of relationships promoted by competitors like Facebook.

While this collaboration/competition relationship (Kelly, cited in Casado and Miguel 2016) is the hallmark of these ecosystems (between them and with all the actors that compose them (Casado and Miguel 2016)), the astonishment aroused by the rapid transition from collaboration to competition, mentioned by the actors of the start-ups I met7, seems to suggest that the adoption of these functionalities is driven by particular economic challenges. These issues relate to the object of “digital memory”, the initiator of a new type of data flow.

7.2.2. Introducing new types of data circulation

Indeed, unlike start-ups, mobilizing dormant content consists, for platforms such as Facebook and Google, of creating additional value from data that are already economically valued by making them use new channels.

First, it involves adding additional layers of information to pre-existing content on the platform, for example to features that were not available at the time of the first publication. This includes, as I have been told, taking advantage of technological developments on the platform to enrich content, for example by using “reactions”, “moods”, “stickers”, etc. or simply by adding information that we could not or did not bother to specify. The publication of a suggested memory is therefore an opportunity to obtain new data that can enrich the information companies have about their users. By “bringing content to the surface”, they recirculate the data that constitute them at new costs and generate new data.

“On this day” is sometimes presented by Facebook employees as a response to a large volume of information that is not sufficiently accurate. Paradoxically, it is by presenting their functionalities as functional solutions in relation to the surplus content that would affect users (overwhelmed by the amount of photos, videos and archived documents) that companies are encouraging them to divest themselves of an ever-increasing volume of data. It appears that, in return, this consideration of the temporal depth of digital content opens a new field of application of algorithmic power. It seems to offer an opportunity to work on new ways to “make the masses of data that make up user profiles speak” by closely identifying what, over time, constitutes them. This internal circulation becomes, when it comes to suggestions of memories, longitudinal and diachronic. Content flows through the same user at two points in his or her life, thus providing feedback through the data layers. Precise and increased, all the data constituting the memory, therefore, makes it possible to increase the income from the sale of advertising space.

7.3. Conclusion

The external circulation of personal content, necessary for the operation of applications, is limited by dominant platforms seeking to preserve and increase their databases. While the emotion and “personalization” produced by these applications and features are one of the recurring arguments of their promoters – to the point of designating “On this day” on Facebook as a “gift” (Weinberger 2017) – they play an important role in the challenges related to data flow and the appropriation of personal content. As such, they also refer to the issues described by Alloing and Pierre (2017) regarding “the production of value and [the] circulation of affects by digital devices” (p. 11). As it comes to the surface, the content of this personal and moving “gift” becomes, for dominant platforms, a valuable tool to specify profiles made up of an ever-increasing volume of data.

Thus, dominant platforms may have, at the same time, found a way to respond to the temporal break between the logic of the flow and that of the archive described by Coutant and Stenger (2010). In a new way, they involve users who are registered in a flow logic in their own archive logic and, consequently, in this strategy of diachronic profile enrichment.

7.4. References

Acquisti, A., Taylor, C.R., and Wagman, L. (2016). The economics of privacy. Journal of Economic Literature, 52(2), 442–492.

Alloing, C. and Pierre, J. (2017). Le Web affectif, une économie numérique des émotions. INA Éditions, Paris.

Casado, M.Á. and Miguel, J.C. (2016). GAFAnomy (Google, Amazon, Facebook and Apple): The Big Four and the b-Ecosystem. In Dynamics of Big Internet Industry Groups and Future Trends, Gómez-Uranga, M., Zabala-Iturriagagoitia, J., and Barrutia, J. (eds). Springer, Berlin, 127–148.

Cecere, G., Le Guel, F., and Rochelandet, F. (2015). Les modèles d’affaires numériques sontils trop indiscrets ? Une analyse empirique. Réseaux, 189(1), 77–101.

Coutant, A. and Stenger, T. (2010). Pratiques et temporalités des réseaux socionumériques : logique de flux et logique d’archive. MEI – Médiation et Information, 32, 125–136.

Denis, J. (2018). Le travail invisible des données : éléments pour une sociologie des infrastructures scripturales. Presses des Mines, Paris.

Fabernovel (2014). GAFAnomics: new economy, new rules. Available at: https://en.fabernovel.com/insights/economy/gafanomics-new-economy-new-rules.

Fiegerman, S. (2013). Memoir app aims to give everyone a perfect memory. Mashable, 18 September. Available at: https://mashable.com/2013/09/18/memoirapp/?europe=true#tfeuRRHICPqC.

Henri, I. (2018). La donnée numérique, bien public ou instrument de profit. Pouvoirs, 164(1), 75–86.

Hutchinson, A. (2017). Here’s how Facebook is automatically telling your good memories from your bad ones. SocialMediaToday, 26 August. Available at: https://www.socialmediatoday.com/social-networks/facebooks-adding-new-memories-reminders-prompt-more-sharing.

Laurent, A. (2016). Facebook, Apple, Google : mais qu’ont-ils tous avec nos souvenirs ? 20 minutes, 17 June. Available at: https://www.20minutes.fr/culture/1867291-20160617-facebook-apple-google-tous-souvenirs.

Lunden, I. (2017). Timehop founder Jon Wegener replaced as CEO by design lead Matt Raoul. Techcrunch, 14 January. Available at: https://techcrunch.com/2017/01/14/timehop-founder-jon-wegener-replaced-as-ceo-by-design-lead-matt-raoul/.

Merzeau, L. (2009). De la surveillance à la veille. Cités, 39(3), 67–80.

Weinberger, A. (2017). Here’s how Facebook is automatically telling your good memories from your bad ones. Business Insider, 25 August. Available at: http://www.businessinsider.fr/us/facebooks-updated-on-this-day-memory-feature-how-it-works-2017-8.

Chapter written by Rémi ROUGE.

- 1 www.timehop.com/about.

- 2 “The irruption of photo memories wants to invite us to inject subjectivity again”, Laurence Allard explained to Annabelle Laurent (2016).

- 3 I use the term platform here to refer to Google, Facebook and Apple, which, with their dominant position in the digital data economy, have undertaken to develop their own memory suggestion services. The term platform refers more generally to the digital spaces where the various actors brought together by the intermediation services offered by these companies converge. GAFA can also be described as “multi-platforms”, as they connect consumers with a variety of content (see Casado and Miguel (2016)).

- 4 The expression “dormant material” is used by Jérôme Denis (2018) in a critical perspective: “the data exist. Or rather, they are already there, ‘dormant’ material, hidden in public administrations and companies, that would simply have to be moved outside the boundaries of the institutions that house them to unleash their potential” (p. 154). Denis refers here to the assumptions of some calls for data opening. Although in digital memories, data are not usually presented as “immediately available”, content that can be converted into digital memories is nevertheless regularly presented by actors as “dormant materials” whose resurgence would reveal their potential.

- 5 On this subject, see, for example, Acquisti et al. (2016).

- 6 Unlike profiles, Facebook “pages” are public profiles for companies, organizations and celebrities, and allow for a lucrative use of the platform. The scope corresponds to the number of users to whom the publication was distributed. For several years, the “organic” (i.e. free) reach of these pages gradually decreased.

- 7 According to one of these managers, Memoir had a privileged relationship with Apple, benefiting greatly from the success of the applications available on its online store, as Cecere et al. (2015) have shown. Apple has developed “Memories” without any proposal to buy the start-up.