5. The Role of Learning Styles in Innovation Team Design

Dr. Sara Beckman, CLO of the Institute for Design Innovation, teaches design and innovation at the University of California’s Haas School of Business, most recently initiating a course on problem framing and solving that integrates approaches from critical thinking, systems thinking, and creative problem solving that is taught to all incoming students. Her research focuses on the value of design to business and the ability to collaborate to innovate. She also has worked at Hewlett-Packard and Booz & Co., and actively consults with a variety of companies now. Sara has B.S., M.S., and Ph.D. degrees in Industrial Engineering and an M.S. in Statistics from Stanford University.

Innovation Process and Design Thinking

Innovation is a process of problem framing and problem solving. Elsewhere in this book, you’ll read about that process, about the tools and techniques that make that process work, about the highly iterative nature of that process, and about getting that process to yield implementable output and sustainable business models. It is a process that is executed by a team, sometimes large, sometimes small, but always by a team. That team has to navigate the process, leveraging at various points in the process the divergent skills, abilities, and styles of the members of the team. In this chapter, we link the phases or key activities of the innovation process directly to the specific skills and styles needed, providing guidance both for the design of innovation teams and for who should lead the activities of the team and when.

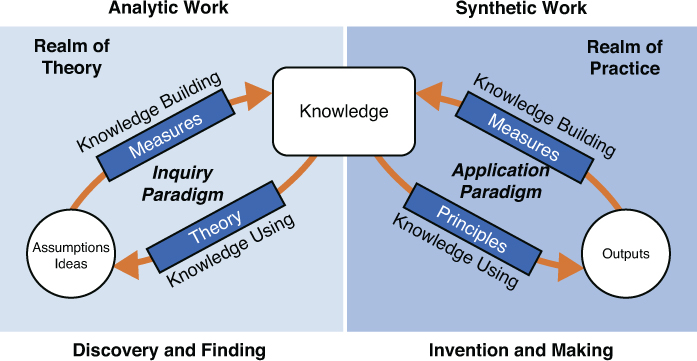

There is a wide variety of descriptions of the innovation or creative problem-solving process (today often called “design thinking”), a couple of which are presented in Chapters 8, “Design Process and Opportunity Development,” and 9, “Navigating Spaces—Tools for Discovery.” At a high level of abstraction, the process simply involves analysis, synthesis, and evaluation,1 key elements of a general problem-solving process.2 These abstract terms are made more concrete in the Illinois Institute of Design’s description of design (see Figure 5.1) as a process of building and using knowledge that has both analytic and synthetic elements, and operates in both the theoretical and the practical realms.3 In the analytic realm, the team focuses on discovery or finding, while in the synthetic phases, the team focuses on invention and making. Movement between the theoretical and the practical realms happens as teams draw insights from what they have observed in the world of practice, convert them to abstract ideas or theories, and then translate the resulting principles back into practice in the form of artifacts or institutions.

Learning Process

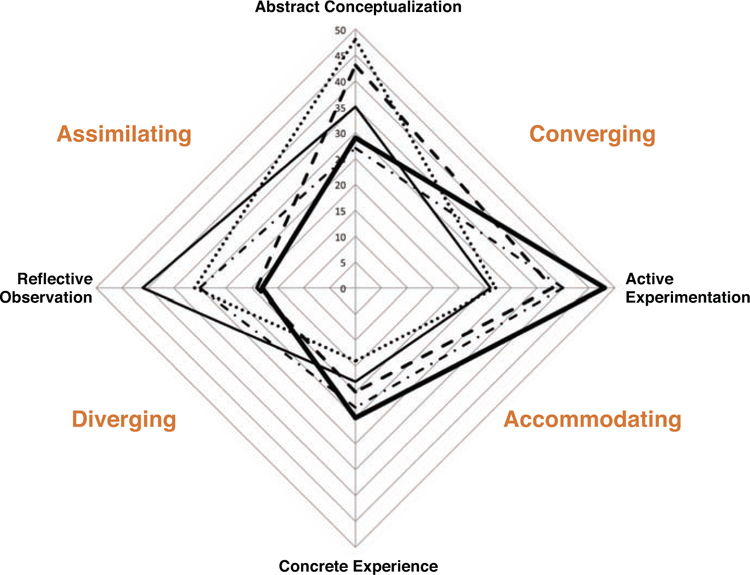

Interestingly, this knowledge-management view of the innovation process maps closely to descriptions of how we learn. In particular, Experiential Learning Theory5 defines the learning process as one in which “knowledge is created through the transformation of experience” and is characterized along two main axes: how we perceive things and how we process things. The spectrum along which we perceive things ranges from the abstract, where we are conceptualizing or thinking about them, to the concrete, where we are feeling them, from the brain to the gut. The spectrum along which we process things ranges from the more passive engagement in reflective observation to active experimentation or just doing. These two dimensions create a four-quadrant model (see Figure 5.2) that defines four learning styles:

1. Diverging learners, who live largely in the concrete world and spend time in reflective observation, are particularly able to view concrete situations from different perspectives.

2. Assimilating learners, who also engage in reflective observation but in more abstract ways, are capable of synthesizing a wide range of information into a useful and logical form.

3. Converging learners, who are also abstract but prefer doing, excel at finding practical applications for ideas and theories.

4. Accommodating learners, who also like doing but back in the concrete world, are good at hands-on learning through practical experience and intuitively identifying risks to take.

We all cycle through this learning process throughout the day as we take in information (diverging), try to fit the new information with our existing mental models (assimilating), adjust those mental models (converging), and then change our behaviors accordingly (accommodating). Thus, we are all capable in all four quadrants, but have particular strength in or preference for one of them. It is these preferences that matter in assembling an innovation team.

Innovation Process and Learning Styles

Now, we can put the two models together to learn something about the ways of processing and perceiving that are needed for the different activities associated with the innovation process (see Figure 5.3). The four key activities are observations, frameworks, imperatives, and solutions.

The Observations phase entails learning in great detail about the lives of the customers targeted by the innovation as described in detail in Chapter 7, “Leveraging Ethnography to Predict Shifting Cultural Norms.” It also entails learning about the industry ecosystem in which the company competes; the core competencies the company can leverage; key discontinuities that might provide an opening for innovation; and industry orthodoxies that, if broken, might yield new ways of framing and solving the innovation challenge.8 All of this work requires empathy and curiosity, both traits of a diverging learner.

Take, for example, a project done for a quick-service restaurant chain that wanted to improve its customer’s experiences. Observation entailed spending time following customers through both drive-through and in-store dining experiences and capturing their stories. One observation, for example, followed a mom of three who had little time to feed her two kids between lacrosse practice and a soccer game. She purchased three meals at the drive-through, put the bag with all the meals in it on her lap along with her small dog, and then as she drove 50 miles per hour down the expressway tried to figure out what belonged to whom as she handed items into the back seat.

Observation also identified key trends such as increased emotional (rather than rational) eating behaviors, desire for healthier foods, and family meal opportunities. It identified core orthodoxies of the fast-food industry that, for example, put drink machines rather than human interaction at the center of the consumer experience. It recognized the core competences of the quick-service restaurant, such as its ability to integrate various elements required to provide excellent customer service and the potential competitive differentiation that might provide.

The Frameworks phase requires taking all the messy data captured in the observation phase and extracting key insights from the data. A wide variety of tools is used at this phase, including customer journey maps9 and perceptual maps10 that facilitate understanding customer needs; industry maps11 that help identify alternative bases for competition; and business model canvases12 that display core elements of a business and their interactions. This work requires the ability to see the big picture, find patterns in messy data, and organize data in ways that clearly communicate the findings to others, all abilities of an assimilating learner.

In our quick-service restaurant example, assimilation entailed identifying common themes across customers, such as the issue our mom had with figuring out what items went to which kid. More important, it required asking “why” enough times to get to the more interesting insight that parents feel guilty about feeding their kids fast food, but don’t feel they have any choice in the fast-paced world in which they live. The innovation team also drew customer journey maps for both the in-store experience and the drive-through, which enabled it to identify critical points of interaction and the highs and lows of the customer experience.

The Imperatives phase moves the team into synthesis work where choices are made as to which of the insights generated in the frameworks phase are most important, and then ideas are generated to respond to those insights. In short, the team goes from framing the problem to solving the problem, or as articulated in Chapter 3, “Framing the Vision for Engagement,” moving from opportunity recognition to value creation. This requires the ability to come up with multiple concepts that meet customer needs and leverage the other findings of the framing phase, and then choosing those concepts that will be built and tested in the market. Converging learners, who are quick to find solutions to defined problems, fit well at this phase.

Although redesigning packaging to make it easier for parents to deliver food to their kids was certainly among the ideas that came up at this phase, the more interesting imperative was around helping parents feel as though they are still good parents when they feed their kids at quick-service restaurants. Focusing on this meaning-based imperative enabled the team to generate a wider range of options—from more nutritious offerings to a chance for a parent to take a deep breath and relax while in line—around something that was truly important to the customer. These ideas leveraged the capability of the organization to provide friendly and warm customer service.

Finally, the Solutions phase takes the concepts generated in the abstract and makes them concrete, building prototypes—ranging from physical products to storyboards to simulations to business models—and taking them back to customers and users for testing.13 This requires the ability to make abstract ideas concrete, the willingness to take unfinished ideas out and share them, and the capacity to hear feedback on ideas, even when that feedback is unfavorable. These are areas in which accommodating learners best fit.

After generating hundreds of concepts, the quick-service restaurant design team chose a few representative ones, built prototypes and storyboards to bring them to life, and took them back out to customers to get feedback. They tested different store designs, including color schemes, furniture styles, and presentations of drinks and condiments. They experimented with different approaches to interacting with customers, serving their meals and refreshing their beverages. In a few quick sessions, they identified which of the insights identified in the frameworks stage were of most interest to the customers, and how to tweak the ideas to be even better solutions before rolling them out throughout the chain.

Building Innovation Teams

We have described four activities that are core to innovation, and matched those activities with the learning styles that are best suited to lead and execute them. This should make putting an innovation team together simple: Just find one person with each of the learning styles, put them on the team, let the right learning style lead at the right time in the process, and innovate away. Of course, it isn’t that simple. First, not surprisingly, people with different styles are likely to have conflicts. The converging learner, eager to find a solution, is likely to be impatient with the diverging learner who keeps asking questions in an attempt to explore the problem further. The accommodating learner, eager to just make something and see what happens, frustrates the assimilating learner who wants to “think about it” some more. Conflict and the other challenges of working with a diverse team can be dealt with in many ways, such as those described in Chapter 6, “Your Team Dynamics and the Dynamics of Your Team.”

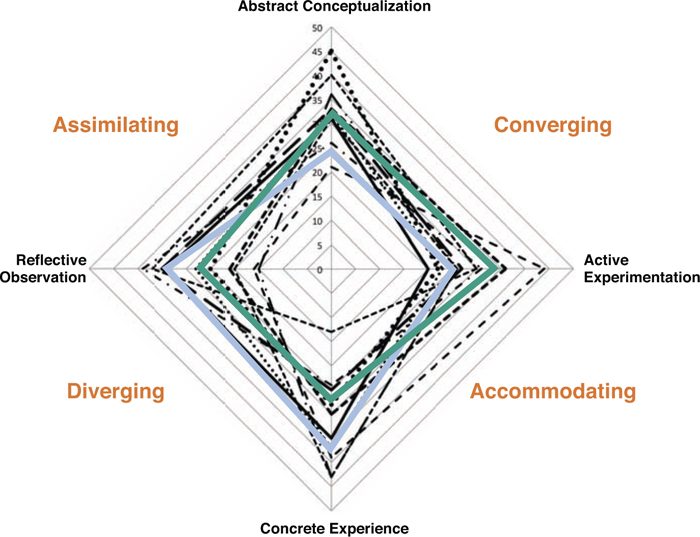

The bigger issue, as we’ve learned through our research in the past few years, is a significant imbalance in the availability of learning styles to construct innovation teams. We have administered Kolb’s Learning Style Inventory14 to more than 3,511 people, including 1,241 MBA students, 113 engineering students, and 1,198 product managers from industry. Table 5.1 vividly shows the challenges for creating diverse, balanced teams. Nearly 50% of the available people are likely to be converging learners, whereas only 3% are diverging learners. Over 70% of the learners are abstract conceptualizers, whereas less than 15% operate in the practical or concrete realm.

The results are striking, and in stark contrast with other findings. According to early reports by Kolb, young children show an even balance of all learning styles, but move toward more abstract thinking as they grow older.16 A study of the general population found that 33% of adults are converging learners, another 33% assimilating learners, 20% accommodating learners, and less than 10% diverging learners.17 A recent study of 179 freshman entering the design, engineering, and commerce (DEC) integrated design class at Philadelphia University found fewer converging (16%) and assimilating (15%) learners, and more accommodating (22%) learners, but still only 1% diverging learners. (The remaining 46% didn’t test into one of the four quadrants, and are what we term “balanced learners.”) In short, the employee populations in many companies, at least as represented by our data, lack the balance found in young children and in places such as the DEC program.18

What does all of this mean for doing innovation in your company? In short, it suggests that you are likely to be dealing with a sizable ratio of converging learners as you assemble your innovation team. The learning styles profile for such a team might look something like that shown in Figure 5.4a. Converging learners prefer problem solving to problem framing, and are thus likely to drive quickly to a solution, perhaps before the situation has been well understood. Our research also shows that having more than one converging learner on a team statistically significantly reduces satisfaction on the team.19 We hypothesize, supported by anecdotal evidence from teams with multiple converging learners, that this is due to the fact that each converging learner argues for a different solution, sometimes to different problems. Thus, your innovation teams are likely to be dominated by a problem-solving orientation and in many cases by conflict over alternative solutions as well.

The converse also holds, because you are highly unlikely to find a diverging learner on your team. This means you are missing someone who can meaningfully represent the customer (or any other stakeholders) with empathy and perspective. You are missing the person who asks, “What would so-and-so think?” as you process ideas. You are missing the person who brings stories20 to the innovation effort that create emotional resonance around which a team can rally and create. Arguably, you are missing the fundamental grounding required to successfully launch the innovation process with the required observation work, and thus the key element for properly framing the problem to be addressed.

Overall, your team is likely to operate primarily in the abstract realm, like the team shown in Figure 5.4b, with far less attention to the concrete. You will see much more talking than doing or making. You will see more theoretical conversations about the innovations you might make and less just trying things out. You will hear more abstractions about customer needs and fewer actual stories about real people whose lives you might transform were you to understand them better. Ideally, instead, you would have a more balanced team similar to that depicted in Figure 5.4c.

Suggestions

How might we remedy the imbalance in our organizations and in particular on our innovation teams? First, we need to recognize that we seemingly have a larger problem with how we are teaching students to learn in the first place. Converging learners “have the ability to solve problems and make decisions based on finding solutions to questions or problems,”22 and have been shown to excel on standardized tests. The U.S. education system is well-tuned to generate such learners23 with its focus on standardization and testing. There is recognition of these problems, and actions are being taken. Philadelphia University, for example, mindfully created a freshman course, Integrative Design Process, that involves a great deal of ambiguity and divergent thinking to introduce students to problem framing and propositional thinking in their first year. The course is required of all freshman in design, engineering, and commerce (DEC), which represents more than half of the university. More such curricula are likely to be developed as the demand for innovative thinking increases.

Meanwhile, here are some places your company can start to diversity the thinking on its innovation teams:

Acknowledge the learning styles that team members have today. When we launch our innovation teams, we show them their learning style profiles (like those shown in Figure 5.4) and discuss the implications for their ability to get through the innovation process as a team. We advise those teams that are dominated by converging learners to step back and ask what problem they are solving. We teach teams not to jump too quickly to solutions, but to examine a set of options. We encourage them to take options back to their customers and get feedback, which keeps them from focusing too much on their own ideas.

Seek diversity in learning styles when hiring and forming teams. It is likely that finding diverging and accommodating learners will require looking in different places than recruiters typically look, particularly companies in the technology space. Diverging learners, for example, often major in the arts, English, history, and psychology and then go into the social services sector or into the arts. Accommodating learners often specialize in education, communication, and nursing. It is thus possible that you have some of these types of learners in your organization, in the training department, the human resources management function, or maybe in the public relations group. But they are probably not finding their way onto your innovation teams. In the experimental spirit of the innovation process we’ve described, try putting one of them onto a team and see what happens.

Help the people you have learn the skills needed. Table 5.2 describes the attributes of people with each of the four learning styles, as well as ways of cultivating ability in those learning styles. More attention to the desired abilities in corporate training, team training, and indeed in corporate culture will help you develop the skills you need to innovate. A. G. Lafley, former CEO of Proctor & Gamble, for example, is famously known for his ability to listen with an open mind, not only to customers but also to his own employees. His sensitivity to the feelings and values of others enabled him to be both a lauded leader of innovation and a well-respected leader overall. In short, these innovation skills can help the organization in many ways.

Leverage the skills you have. After your innovation teams are aware of the learning styles available to them, they can leverage those skills at the appropriate point in the process. If the team is lucky enough to have a diverging learner, for example, it should let that person lead the team through the observation work of innovation. If, on the other hand, the team has no divergers, it might need additional support to learn and execute those skills. In some cases, the team might want to outsource the observation work to others. In other cases, it might simply have to pay more attention to engaging in observation, forcing itself, for example, to avoid jumping too quickly to single solutions.

In this chapter, we’ve introduced you to a model that integrates the innovation process with the learning styles needed to execute that process. We’ve warned you about the imbalance in learning styles available to today’s innovation teams, in particular the dominance of converging learners and the paucity of diverging learners. Finally, we’ve given you some actions you can take to provide your teams with the needed skills for each of the innovation activities. We hope this will lead to increased awareness of how to engage in observation, (re)framing, ideation, and experimentation as you strive to improve innovation in your organization.

Endnotes

1. The basics of design have been described in many ways over many years and across many disciplines. For some of the basics, see M. Asimow, Introduction to Design (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1962).

2. At some level, innovation simply entails framing problems or opportunities in different ways. It thus falls in the category of problem-solving processes such as described in, for example, H. A. Simon, The Sciences of the Artificial (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1969).

3. C. L. Owen, “Design Research: Building the Knowledge Base,” Design Studies, vol. 19, no. 1 (1998): 9–20.

4. Adapted from C. L. Owen, “Design Research.”

5. D. A. Kolb, Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1984).

6. Drawn from D. A. Kolb, Experiential Learning.

7. Adapted from M. Barry and S. L. Beckman, “Innovation as a Learning Process: Embedding Design Thinking,” California Management Review, vol. 50, no. 1 (2007): 25–56.

8. P. Skarzynski and R. Gibson, Innovation to the Core: A Blueprint for Transforming the Way Your Company Innovates (Boston, MA: Harvard Business Press, 2008) describes these areas of inquiry as the five lenses through which a situation can be viewed to generate innovation.

9. There are many good examples of customer journey maps online, one example of which is found at http://blogs.hbr.org/cs/2010/11/using_customer_journey_maps_to.html, July 15, 2013.

10. For more background on perceptual maps, see J. R. Hauser and F. S. Koppelman, “Alternative Perceptual Mapping Techniques: Relative Accuracy and Usefulness,” Journal of Marketing Research XVI (November 1979): 495–506.

11. Mapping the bases on which companies compete in an industry against the characteristics desired by customers yields new opportunities, or “blue oceans,” as described in W. C. Kim and R. Mauborgne, Blue Ocean Strategy: How to Create Uncontested Market Space and Make Competition Irrelevant (Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press, 2005).

12. A. Osterwalder and Y. Pigneur, Business Model Generation (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons, 2010).

13. For a detailed description of many ways of prototyping, see B. Buxton, Sketching User Experiences (San Francisco, CA: Elsevier, 2007).

14. D. A. Kolb, Experiential Learning.

15. K. Lau, A. Agogino, and S. L. Beckman, “Global Characterizations of Learning Styles among Students and Professionals” (proceedings of the International Design Forum, ASEE National Conference, Atlanta, GA, 2013).

16. A. Kolb and D. Kolb, “The Kolb Learning Style Inventory—Version 3.1, Technical Specifications” (HayGroup, 2005).

17. D. Kolb, “Learning Style Inventory Technical Manual” (Boston, MA: McBer and Co., 1976).

18. The DEC core curriculum comprises coursework in integrative design process, business model innovation, applied ethnographic research methods, and science-based systems thinking and was created to expose students regardless of major (design, engineering, or business) to all learning styles. One of the main hypotheses of the DEC core curriculum is that greater exposure to a variety of learning styles and experiences, coupled with exposure to the various discipline domains, will make for better prepared teams to integrate divergers, convergers, assimilators, accommodators, and balanced learning styles in practice.

19. K. Lau, A. Agogino, and S. L. Beckman, “Diversity in Design Teams: An Investigation of Learning Styles and their Impact on Team Performance” (proceedings of the Mudd Design Workshop VIII, Claremont, CA, 2011).

20. S. L. Beckman and M. Barry, “Design and Innovation through Storytelling,” International Journal of Innovation Science vol. 1, no. 4 (2009): 151–160.

21. Each line on the graph depicts the profile of an individual based on the results from the person’s Learning Style Inventory test. By plotting all the lines on one graph, you can see the overall profile of the team.

22. D. A. Kolb, Experiential Learning.

23. S. Khan, The One World Schoolhouse: Education Reimagined (Twelve, 2013).

24. Drawn from A. Kolb and D. Kolb, “The Kolb Learning Style Inventory.”