9. Navigating Spaces—Tools for Discovery

Photo credit: Janelle Wysock.

Natalie Nixon, Ph.D., is a hybrid thinker, synthesizing the creative and the analytical to arrive at innovative opportunities. A design-thinking researcher, she has 15-plus years’ experience as an educator and has worked in the fashion industry as an entrepreneurial hat designer and in sourcing for The Limited Brands in Sri Lanka and Portugal. Natalie’s consulting interests are in business design and in applying strategies from the fashion industry to other realms. Natalie earned her B.A. (cum laude) from Vassar College, Anthropology and Africana Studies; M.S. from Philadelphia University, Global Textile Marketing; and Ph.D. from the University of Westminster, London, Design Management.

Introduction: What Is the Discovery Process?

Problem solving has become a commodity activity; the real added value is in framing the problem, and being certain that you’ve even asked the right question. This chapter discusses the tools to frame the problem and navigate the innovation process, with emphasis on the phases of discovery and formulation, as mentioned in Chapter 3, “Framing the Vision for Engagement.” If we understand innovation as a discovery process, the best tools to navigate this process are ones that are adaptive, fluid, and accessible. Innovation is grounded in both inspiration and invention, and as such, it cannot be restricted by inflexible contraptions. Think of sailing, cooking, and jazz improvisation. In each of these endeavors, a concrete skill set, structures, and clear parameters are essential. However, those structures are meant to be fluid, meant for rebounding, to be played with and to be tweaked. Similarly, the best tools for innovation are those that allow for structure and flow. Diverse tools are needed, much like the parable of the six blind men and the elephant: Each man described completely different qualities of the elephant depending on whether he was touching the animal’s husk, ear, or foot. Using only one tool will only lead us to see a portion of the opportunity ahead of us.

This chapter is based on research and interviews with 12 diverse and distinctive practitioners from innovation firms and consumer products companies.

The Purpose of Tools

We typically think of tools applied to do physical tasks. In environments that are complex and ambiguous, it is important that tools are utilitarian, process-oriented, and also adaptive. Tim Brown has said, “The design process is best described metaphorically as a system of spaces rather than a predefined series of orderly steps” (“Design Thinking,” HBR, 2008). Extending that notion, innovative outcomes are a result of proceeding through a system of spaces, not linear steps.

We end with definitions of a tool by the 12 practitioners interviewed for this chapter. For simplicity’s purposes we’ll start by defining a tool as an adaptive device that provides a means to an end. That device could be a tangible object or a process.

The Repertory: An Adaptive Toolbox

What follows is a repertoire of seven foundational tools (see Figure 9.1) to assist you in sparking empathy and curiosity about who your user is, what his or her real needs are, and how you can discover new insights about the extension and capacity of your offering. By practicing and applying these tools to various situations (see Figure 9.2), you will develop and customize your own portfolio of methods that will enable you to adapt to the changing needs of your customer and allow for structure and flow.

Teaming

As you learned in Chapters 5, “The Role of Learning Styles in Innovation Team Design,” and 6, “Your Team Dynamics and the Dynamics of Your Team,” getting good at teaming requires an organization to view itself as an organic, evolving ecosystem. The formation and sustaining of teams involves setting up the right human dynamics and the correct problem definition. This is one of the most critical steps in any of the subsequent innovation techniques because the real value comes from the people in the organization. Developing a productive team could take six to eight weeks to allow for latency in conversations to emerge. One of the biggest mistakes in teaming is not allowing for the right diversity in the room. For example, the team should include people beyond the core team working the problem so that the process taps into naive eyes, who tend to help the discovery process. Include skeptics and early adopters on the same team because this causes creative abrasion, a friction between two seemingly opposing ideas that results in more innovative insights.

Lastly, an important part of teaming is tracking the team according to metrics such as safety, support, creative expression, value, and truth. These particular metrics come from the work of Mukara Meredith, whose consultancy, MatrixWorks, outlines a process to help groups view themselves as living systems. If one of those metrics is out of whack, there are corresponding activities to set new ground rules. This example points out the dynamic (not static) way to approach maintaining a team that is part of an ecosystem.

Brainstorming and Charrettes

Brainstorming is a synthetic act and its value is that it is a tool for reflection. The important thing to remember about brainstorming is, as Manoj Fenelon of PepsiCo reminds us, “Creativity needs constraints!” Constraints actually make the creative brainstorming process more fun and productive. For example, time limits are helpful constraints. Another constraint might be that you require a particular word (say, “rose,” for example) to be included in every proposed solution during the brainstorming session. Not everyone is a proponent of brainstorming because it can devolve into one huge divergent brain dump. The purpose of a brainstorming session is often less about the final idea and more about making people on the team feel as though they are part of the process. As you grow in your brainstorming capacity, it might be helpful to develop a library of exercises.

Brainstorming is an in-out process that speaks to the organizational culture, because it definitely requires an emotional readiness and willingness to expose oneself. Not all organizations are up to the task for brainstorming.

One of the wonderful outcomes of brainstorming is something John Heath, Senior Vice President of Innovation at Chobani, calls “wet paint”—because nothing should ever seem as though it is fully baked. Otherwise, it appears as if you are telling someone what to do, instead of valuing their engagement in a process.

The charrette is a structured brainstorming and consensus-building methodology used for problem solving among diverse stakeholders. It has been used traditionally in the architecture and urban-planning fields to unite stakeholders and engage in conflict resolution. Charrettes are a proven means for generating actionable opportunities for the purposes of innovation. The purpose of a charrette is to share ideas within a succinct time frame in an interdisciplinary setting. Teams are asked to produce multiple variations of an idea, in rapid succession, so that the larger group can review a large quantity of ideas. It is better to have 25 ideas with 3 potentially great ones than to spend many hours coming up with “the one good idea.” The structure of the charrette enables you to take advantage of the convergence-divergence process that is key in any creative process. Divergent thinking comes with the free-flow, fire-hose push of ideas outward. Convergent thinking is equally, essentially, for sorting and sifting through all of those ideas, identifying what bigger ideas begin to surface, and acting on particular ones.

A two-day charrette might be structured in the following way, as described by Nick Hahn of Vivaldi Partners: On day one there is lots of divergent, big-picture thinking. On day two convergent thinking occurs utilizing “dot-allocation”—that is, participants place dot stickers on the ideas that they believe are most actionable. Day two is more tactical and involves figuring out how your team will actually do what has surfaced. Cindy Tripp prefers to use dot-allocation to highlight the ideas that scare participants regardless of viability because those spaces tend to debunk preconceived notions and lead to innovative insights.

Teams should also ask, “What is the cost of failure if the idea does not work?” and, “Who else is doing this?” Teams need to produce many ideas very quickly in order to create a broad range of ideas that can be vetted by the larger group. Keep in mind that these identified opportunities can be small ideas, and result in subtle shifts that will have large implications for innovation in organizations of any size or scope. Ideally, the charrette consists of at least two sessions of two to three days each, with one- to three-month interims during which stakeholders are exploring the actionable ideas that have surfaced and conducting more research. In this way, the charrette is part of an iterative process.

Prototyping

Prototyping is the process of representing an idea in rough-draft form. As Chapter 8, “Design Process and Opportunity Development,” details, prototypes can be low fidelity or high resolution depending on your goals in creating the simulation. Pop-up retail is one way to prototype the tangible and the intangible; improvisation and role-playing are means to prototype new service delivery ideas, brand stories, or a customer journey. Prototyping places value on failing early and often, before millions of dollars have been invested in new hires or new technology. The reason to prototype is to learn things. A prototype gives tangible access to examine three parts of the discovery process: Here is what we are testing; here is our hypothesis; here is what we hope to learn. It is data that can be used to generate more data.

Proximity to the user and the conditions in which you do the prototyping are essential. For example, some companies take the Skunkworks approach and sequester the prototyping team away from the politics and business pressures of the daily work. Prototyping has different uses at different points in a project.

Observation and Fieldwork

Fieldwork is a critical methodology in anthropology and many organizations have begun to hire anthropologists. It requires people to immerse themselves in the environment of the user and utilize skills such as interviewing, observation, participant-observation, and a range of documentation techniques like note taking, photography, and video recording. Greater insight about the use of anthropology and ethnography and specifically fieldwork can be found in Chapter 7, “Leveraging Ethnography to Predict Shifting Cultural Norms.”

Mark Raheja of Undercurrent reminds us, “There is what people say, and then there is what people do!” Observation ends up being many innovative companies’ most accessed tools, and the most overlooked in run-of-the-mill organizations. Some organizations incorporate digital tools such as Evernote to tag and reference visual observations, and end up creating a bibliography. Observation is incredibly important and can deliver a tremendous amount of data if done properly; note that it’s what you see, not what you interpret. Noting that “a juvenile delinquent is standing around in the middle of the day looking suspicious” is interpreting; noting that “it is 2:15 on a Tuesday afternoon and a boy is sitting with an iPod, headphones, baggy jeans, a T-shirt, and a baseball cap on a corner at a bus stop” is seeing.

Fieldwork is a way to connect to the work at hand, to get to stories and then analyze those stories. It helps you learn the context in which an object, a service, or an experience lives. As Annie Chang of Jump Associates explained, “A lot of the work we do is emergent—when it comes to ambiguous challenges, we need to let those themes emerge over time.” Jordan Fischer of Gravity Tank points out that fieldwork allows for the ambiguity that is part of letting themes emerge over time.

Audits

An audit is a detailed cataloging of a product or service from various perspectives. Audits are used in the innovation discovery process by taking inventory of a brand, product, or service; one must conduct detailed observation, interviewing, and secondary research. For the purposes of innovation, “design audits” and “brand audits” are often helpful. Sometimes a good place to start is with what is commonly known as the 3C’s of the organization: the company itself, the customers of that product or service, and the competitors. Audits work well because they require narrow focus and detailed attention to aspects of the product or service that you typically might have ignored. For example, if auditing a product, you would note the color, textures, and form that are embedded in the design of the object. It is helpful to look broadly at related products. Additionally, one can use audits when exploring broader, higher-level topic areas that are helpful for business improvement. So, for example, if “convenience” is the topic at hand, an audit is helpful for taking stock of convenience in multiple areas and environments. What are all the ways to be convenient? You might look at fast-food restaurants, public restrooms, or luggage. Each of these is an on-ramp to the field of convenience.

Draw It: Visual Mapping and Diagramming

A component of the innovation process involves looking ahead, identifying what artists call “negative space” (that space in between the outlined contours), and attempting to see what is not yet visible to the masses. When done effectively, visual mapping builds consensus around a problem and explores possible solutions in order to articulate the final vision. “If I have a good designer that can draw pictures and articulate the right thing, then I can get people to really work well,” says John Heath at the Chobani offices in New York City. He points to a huge chalkboard full of beautiful illustrations of fruits and vegetables and container shapes that illustrate potential new flavor combinations for their yogurts. He explains that Chobani has begun to use this method of live chalkboard drawing to pitch new ideas; instead of using PowerPoint, one of their artists on staff draws the concept and they end up with live, nondigitized infographics: “Once we have identified the new product, story becomes important because that is the envisioning part.” Manoj Fenelon of PepsiCo recalls a colleague who presented a strategic plan to a CEO as a visual map, almost in cartoon form. It was effective because it caused people to lean in and engage.

When presented with a sketch or a drawing, people tend to lean in, and engage with the big ideas. Dan Roam, author of Back of the Napkin and Blah, Blah, Blah, reminds us that we are hard-wired to respond to visual representations, and that she who can draw it gets the negotiation done, gets the deal done, and receives the ultimate buy-in from the team. When clients participate in the pattern emergence, they own their business competencies and have a firm grasp of their own offering as well as those of their competitors. The business model canvas, presented in Chapters 10, “Value Creation through Shaping Opportunity—The Business Model,” and 11, “Developing Sustainable Business Models,” is an example of a visual mapping tool. Like most visual mapping tools, it is helpful in distilling complex ideas. The canvas helps people see each component of their business to help support their strategy. When you can finesse tools such as the business model canvas, it is easier to break the rules.

Gordon Hui and Mai Nguyen explain how, at Smart Design, “we like real consumers,” and because they are driven to put people first, they use “Consumer Snapshots” as a way to highlight key takeaways of a particular user group. These snapshots are three-dimensional thumbnails of real people, not personas that are composites of people, and thus tend to be a simplification of the user. The messiness of consumer snapshots shows the messiness and complexity of the issue as well. Annie Chang from Jump Associates explains how they frequently use the whiteboard and notebooks to visually record meetings; it grants assurance and makes people feel heard.

Another powerful tool is customer journey mapping, which visually charts the physical and emotional touch points a customer has through interacting with your service or product. A complete customer journey map starts before the need and ends after the solution has been consumed and discarded. For example, a user with a potential medical need could begin his journey prior to diagnosis of an illness, at the point of a preexisting condition, and it could flow all the way through the stages of disease progression with a textured noting of emotional and physical considerations for the user, his family, his medical community, and so on. A hotel would begin plotting their customer journey map at the point of awareness of the offering (the Web? word of mouth?), and incorporate the travel to the hotel (airport experience? cab or designated van service?), detail phases of the stay (welcome, room experience, walking through hallways, etc.), departure, and resonance of the stay in the user’s memory. Even traditional consumer product journey maps begin with research and awareness and extend through use to customer service when there is a post-purchase issue and on to disposal and reflection. Although many companies focus on product or service performance alone, full customer journey mapping highlights opportunities to meet latent needs in marketing, brand communications, the business model, customer service, and more.

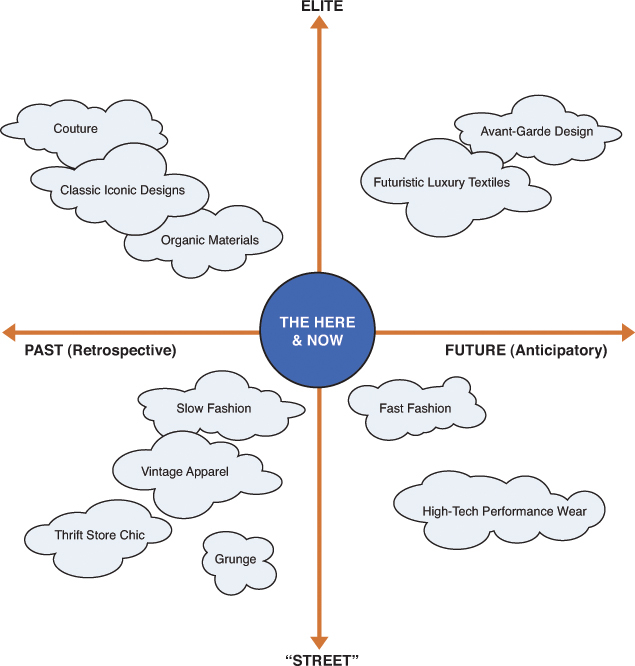

Adapted from the original by Natalie Nixon and Johanna Blakely, “Fashion Thinking—Towards an Actionable Methodology,” Fashion Practice, Vol. 4, issue 2, p. 159.

Figure 9.3 “Fashion Thinking Matrix” by Natalie Nixon and Johanna Blakley—an example of visually diagramming by using a 2×2 matrix.

Improvisation and Role-Playing

Improvisation is a tool that both sparks and helps reimagine an idea, a concept, a conversation, a way of seeing, and so forth. It is a collaborative discovery process that challenges the status quo through exploration and experimentation, and requires participants to make different choices than they typically would make. In this way, new and varied possibilities are created.

Sevanne Kassarjian of Performance of a Lifetime explains that improvisation starts with the “offer”—any new idea, situation, or dynamic that occurs in a scene—and these are the sparks for innovation. Although typically we might respond to new ideas with criticism (“I’ve got a better or different idea”), in improvisation, “offers” must be accepted and built upon—you say “yes, and....” Improvisation emphasizes the value of building the idea together rather than asserting one’s superiority through identifying weakness. And it requires keen and creative listening. This might be a new paradigm for your team. Improvising gets you invested in what others are thinking and feeling, and provides the creative impetus to build and create with their multiple offers.

Bodystorming is a kinesthetic form of brainstorming, in which participants imagine that the product or service actually exists and physically interact with the imaginary product; gaps in function and form come to light. For improv to be used as a tool in a work environment, the organizational culture must be one where employees’ emotional component is allowed to be visible.

Synthesizing the Repertory

There are five key themes that surfaced in interviews with practitioners about adaptive tools for innovation:

1. See the Latent Need: Be diligent and self-conscious about seeing emergent patterns that are right in front of you. Valerie Jacobs emphasizes to practice “seeing” to help you identify the unmet, latent need. Use recording mechanisms such as pen, paper, and your smartphone camera; keep a whiteboard in some area of your office. Pattern-finding tools, which facilitate structured, lateral thinking (making connections between multiple data points), and lateral inspiration, are key. The business model canvas, blue-ocean framework, and 2×2 matrices are helpful. For example, Michelle Miller’s “whole-system collaboration model,” shown in Figure 9.4, is a redesigned 2×2 matrix that helps you to map stakeholders in a holistic manner.

©2013 Michelle Miller

Figure 9.4 Example of a stakeholder map for whole-system engagement, developed by Michelle Miller (from “Everyone Has a Role: Whole System Engagement Maximizes Collaboration,” Michelle Miller, 2013, The XXIV ISPIM Conference).

2. People Are Essential: Harold Hambrose points out that Electronic Ink’s added value is in their skilled people, who are keen and focused observers. If you don’t have that internally, build out hub-and-spoke models consisting of a tribe of people who can give you that skill set. When you’re investigating users, attention has to be put on not only what Hambrose calls “the procedural truth” (planned processes) and “the mechanical truth” (how do I set up my physical space to support the procedural truth), but also the “human truth.” Cindy Tripp pointed out the need to get the right people in the room, allow for latency in conversations, and remember that healthy tension, also known as creative abrasion, is good. Have face-level interactions with your clients and your end users—they are who Mark Raheja calls “your co-conspirators.” Proximity and immersion into the process are essential. John Heath knows that Chobani’s advantage is in its people: “That is the only way you can explain the Chobani product versus some competitor product...we have access to the same machines and technology. Different choices are made about ingredients because a different staff of people are driving different values.” Heath refers to this as ecosystem of design where there are organic interdependencies among departments. Nick Hahn likes to reframe the question in human terms: “It is ‘outside-in’ beginning with the consumer.” Hahn also talks about the need for “strategic intuition”: “Intuition is how you get to something based on collective memory. With strategic intuition, you are getting to ‘that something’ in a more structured way, for example, by using a business model canvas.” Since everything has already been invented, one must appropriately scan all that has come before. Manoj Fenelon values ethnography, “even bastardized ones,” to help you get out into the real world, beyond the spreadsheet.

3. Agile Hybridity: There are layers of dual processes in tools for innovation. For example, it will always be structured by the constraint of time, so adapt by using both quantitative and qualitative data. It is important to balance the qualitative research of fieldwork with quantitative research so as to not get too far in the weeds. Quantitative research shows us the pattern and the “what”; qualitative research provides the deeper story and the “why.”

Gordon Hui points out the “internal-external” dynamic: Strategy’s legacy has been to focus internally, but this focus doesn’t stretch one’s capacity; design’s legacy has been to look externally, at the customer. When integrated, these two lenses become a dynamic duo. Alain Sylvain reflects that the main tool for his “nonprocess” is creativity, or organized chaos, in which simplicity needs complexity.

4. Story: Each of the foundational tools described in this chapter can contribute to developing story for the product and service in order to give narrative, shape, and form and can be used as a helpful guide for the company. Story from the inside of the corporation out can also be effective in branding and messaging to the public. The increasingly popular use of transmedia storytelling utilizes multiple platforms to tell a brand’s story, annotated by the user: in a movie, a novel, a graphic novel, a website, and an animated short film. Think of the Batman franchise, Mike and Ike candy, and the Old Spice franchise, which allow for open-source additions.

5. What-If Money: One of the things that these tools point out is the need to budget for instinct and “latent ROI” or “not-asked-for money” in budget lines, enabling your team to play with resources, time, and the unexpected discoveries. This requires an acknowledgment for time and space to allow for failure of 99% of the ideas. How does one cultivate and get better at instinct? Some of it is about time on task and repeatedly allowing for structures in the work practice that enable people to engage in instinct. Instinct also comes from immersion in the right context and observing different ways of practice. As Mark Reheda says, “Are you a sponge or Teflon? Are you listening or hearing?” Instinct is a muscle that has to be developed.

Applications of the Adaptive Toolbox for Innovation

In sumary, we offer an overview of which tools to use when (see Figure 9.5). Frameworks are helpful to use alongside tools because they offer a snaphot at complexity that is otherwise difficult to articulate. Frameworks are descriptive, and tools are prescriptive. It is important to understand the intent behind the use of the tool.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to acknowledge the following practitioners for making the time to be interviewed for this chapter.

Here are their own definitions of a tool:

• Annie Chang, Strategist, Jump Associates: “A known/defined way to approach something.”

• Manoj Fenelon, Director of Foresight, PepsiCo: “A tool is anything you can use again and again, and that allows for the tool itself to change.”

• Jordan Fischer, Lead Strategist, Gravity Tank: “An artifact that performs a series of functions.”

• Nick Hahn, Senior Partner, Vivaldi Partner Group: “A thing, idea, or construct that accelerates your ability to accomplish something. I don’t like the word tool, because it isn’t about the tool, it’s about the builder!”

• Harold Hambrose, President, Electronic Ink: “A tool is anything we can leverage to move us a step forward. A tool might be a conversation, a technique, an object. But like any tool, these things are consciously used and we’ve got to demonstrate your ability to effectively manipulate them.”

• John Heath, Senior Vice President of Innovation, Chobani: “When used properly, a tool can help accelerate the process of identifying problems and solutions.”

• Gordon Hui, Global Director of Business Design and Strategy, Smart Design: “A tool is just a process, a framework, a deliverable output that allows you to enable a set of insights that are external or internal—allows you a lot of flexibility in thinking of a what a tool is.”

• Valerie Jacobs, Vice President, Managing Creative Director, Trends, LPK: “A tool is anything that helps somebody get their idea from their head into reality, or on paper.”

• Sevanne Kassarjian, Lead Trainer, Performance of a Lifetime: “We talk about improvisation as a tool that both results in innovation, and it’s an innovation in and of itself.”

• Michelle Miller, Organizational Architect, Synexe: “It’s like having a quiver full of different arrows. Like how a handyman has a box carried around, or a toolbox on their waist....You have to pick your favorites—a virtual but fairly lightweight tool kit!”

• Mai Nguyen, Business Development Director, Smart Design: “It is simply something that enables you to discover.”

• Mark Raheja, Strategy Director, Undercurrent: “A tool is something that you draw on to help you achieve a goal, and carry out an objective. Sometimes it’s a person, sometimes it’s a lens, sometimes it is specific, hard and tangible. There is a thrill for us in building the plane in midair, versus having a ‘research tool kit.’ There is a moment when every strategist invents their own tool.”

• Alain Sylvain, Founder and CEO, Sylvain Labs: “I don’t really believe in tools. Tools are more for the client than for the process. My un-process is my tool...creativity is my tool and validates my un-process.”

• Cindy Tripp, President, Cindy Tripp & Company, LLC: “A tool is something that is useful. Unlike gardening tools, which are specialized and rigid, a tool for discovering innovation can be created in the moment, for the moment. They are not static.”