13. Broad Thinking—Connecting Design and Innovation with What Women Want

Yvonne Lin is an expert at considering gender in developing compelling and functional solutions to complex design problems. She is one of the founding members of 4B and the Femme Den. She was a named a Master of Design by Fast Company. Previously, she was an Associate Director at Smart Design. She has a B.A. in Visual Art and a B.A. in Engineering from Brown University. She is the inventor on more than 20 patents and has designed products and experiences for companies like Nike, Johnson & Johnson, Hewlett-Packard, American Express, LEGO, Pyrex, Nissan, and Under Armour. She also spends a lot of time skiing, rock climbing, and putzing around her apartment making small art projects.

On writing projects, Yvonne frequently collaborates with Boris Itin, whom she would like to thank for his contributions to this chapter.

Every year, thousands of corporations invest billions of dollars into designing and making toothbrushes, flowerpots, cars, remote controls, and all the thousands of products that we interact with every day. As illustrated throughout this book, innovation is a complex process involving people with a wide range of skills. Designers, engineers, sales and marketing teams, advertisers, business strategists, and many other talented and hardworking people strive at the best of their abilities to satisfy the customers, male and female alike. And yet I know so many women who wonder:

“Do they have a clue about who I am?”

Women buy or influence 85% of all consumer purchases. Yet they feel that the majority of products are not meeting their needs. This is true across the vast majority of industries. Despite buying or influencing the purchase of 90% of all consumer electronics, only 15% of American women think that computing and mobile products are designed to be appealing. Despite making 69% of the household health decisions, 66% of American women feel misunderstood by healthcare marketers. Despite controlling 73% of household spending, 84% of American women feel let down by the level of quality and service they get from financial companies. Despite purchasing 60% of cars and heavily influencing the purchase of an additional 30%, 74% of American women feel like they are misunderstood by the automotive industry.

Most companies are aware of how important the women’s market is. They try very hard to appeal to women on all levels, from marketing to design to customer service. Yet they often admit that they fail. This is not a failure of intent or of lack of effort; this is a failure of understanding. Driven by misconceptions and adherence to stereotypes, many companies resort to a “pink it and shrink it” design strategy. Instead of appealing to women, they ended up insulting their customers.

To create a good product, a designer has to understand the user. This is also true if a user is a woman. Here comes the great challenge of design: While the majority of consumers are women, 85% of product designers and engineers are men (see Figure 13.1).

There are few things that men find as difficult to understand as women. The lack of understanding spills over into the design and innovation industry.

Five years ago, three of my female colleagues and I noticed this opportunity and we launched an experiment within Smart Design called the Femme Den. Today, we continue to design for the 4 billion women in the world with the design collective, 4B. We represent educational and professional expertise in industrial design, design engineering, design strategy, design research, and architecture. Between us we have over 35 years of professional design experience. The Femme Den achieved deep traction with early clients including major corporations in medical, consumer electronics, housewares, automotive, and sporting-goods industries, such as Johnson & Johnson, GE Medical, Hewlett-Packard, Proctor & Gamble, LEGO, Nissan, and Nike. Press coverage on this approach was given in Fast Company, ID Magazine, New York Times, and more. Our designs have won multiple awards, have become bestsellers, and have made women happy.

Four Key Insights into “Broad Thinking”

We take a holistic and interdisciplinary approach to understanding how women think and make decisions. Our path to understanding women has been long and full of unexpected discoveries. Like anthropologists, we studied women in their natural habitat. We followed them when they were driving, shopping, cooking, cleaning, talking, and playing. We observed them at their jobs, in their homes, and with their families. We studied trendsetters and more mainstream women. We analyzed how women interact with products and services at every stage. We listened carefully to what women said and, even more carefully, to what they didn’t say. We learned many things not mentioned in design literature or discussed at design conferences. Based on many years of design and research, we developed strategies and tools to analyze women’s needs and to make products and services that they appreciate. In particular, we have identified four issues that are important for women but are often ignored in the current world of innovation and design. We call our approach Broad Thinking. Understanding women and gender issues will enable designers to deliver better products and services. Gender can be and should be a part of any design project just as ergonomics, function, or aesthetics are. Following are four key broad thinking areas and some examples of how they work.

Women Think About “We,” Not “Me”

To design a successful product, a designer should first ask himself or herself the following questions: “Who is the user?” and “What does this person want and need?”

A product doesn’t become successful just because it has high performance. It becomes successful because it fulfills people’s needs. Men and women might have different sets of needs from the same product. A source of these different needs comes from how the two genders define themselves differently. Men tend to think in terms of “I.” A man buys a product because he likes it and he is going to use it. Women tend to think about “we.” A woman buys a product because she likes it and she wants to use it; but she also wants her partner to enjoy it, her kids to understand it, and her parents to approve of it. She also wants the product to fit her lifestyle and her home.

When designers try to make a successful product for women, they should be very well aware of this difference. Our team didn’t recognize this immediately. It took years of design experience to fully appreciate how impactful this distinction is. We always start design projects with an in-depth qualitative research. One of the tools we use is a “chat.” A chat is a small informal single-gender conversation generously lubricated by wine, beer, and food. We couldn’t help but notice this mind-set difference between the groups of men and women. The women quickly introduce themselves, as well as their children, husbands, parents, and pets. They use the pronoun “we” throughout the chat. They are constantly referring to something their kids did or didn’t do, to what their husbands like or hate. They talk about their relatives and friends. They define themselves as a result of a social interaction matrix. They describe their homes and how much effort they invest in having their homes harmonious and happy. When the men describe themselves, they specify their age, work, and interests. They use the pronoun “I.” Often, it’s not until the second hour of the chat, when prompted directly, that they succinctly describe their families.

The problem is that numerous products are designed to please a single person. Designers consider the user an “I,” not a “we.” This approach does not reflect their female customer’s perspective. Women do 85% of the shopping and they judge products through the lens of “we,” not “I.” A woman buys for herself, her family, and her home. Her list of user requirements is much longer. This means that when the product is being judged through her eyes, it often falls short of her standards. To please her, designers need to think about “we.” They need to consider the complex web of user requirements from multiple viewpoints. Let us look at some examples.

A man needs a thermometer. He walks into a drugstore, walks to the corresponding section, and takes a look at the thermometers. His eyes fall on a classic stick thermometer. He sees that the temperature gauge looks easy to read. “I can use it,” the man thinks as he buys it.

A woman walks into a drugstore and she looks around. “I can use it,” she thinks about the classic stick thermometer, “but what about my kids? No, they are going to hate it.” The thermometer is pointy and it looks like a long, scary needle. Her six-year-old son hates needles and he will be upset.

Nearby are various Vicks thermometers. They look safe and comfortable—not intimidating at all (see Figure 13.2). They are interactive—her son can see how the temperature indicator changes as he keeps it under his armpit. “Wonderful,” his wife thinks, “we can all use it.”

A man buys a video game console to shoot monsters from outer space and drive tanks through the enemy’s defense lines. “I like playing these games,” a man thinks as he buys it. Naturally, most video game consoles were designed for young to middle-aged men. Except for one.

When the Wii came out, the female market literally exploded. The consoles were immediately sold out and it took months of patient waiting to get your hands on one. Why did women like the Wii so much? Amazon user reviews answer this question quite clearly:

“We had more fun, and more laughs, playing those games together than we did playing our individual games.”

“The Wii is the best way to go because there are more multiplayer games that are age-friendly from parent to child.”

“My father, who hates video games as a way of spending time and money, thinks that the Wii is great, and was like a little boy playing it. (He’s 55.)”

Numerous high-ranking reviews by women stress the same point. They think in terms of “we,” not “me”; they are looking for a product that everybody in the family can enjoy and play together. They are excited that all three generations—grandparents, parents, and children—and both genders can use it. The Wii console offered universality and a joint gaming experience.

To summarize this point, a man looks for a product that would make him happy whereas a woman looks for a product that would make her whole family, including men, happy. A man’s requirements for a product are a subset of a woman’s longer list of requirements. If a man is satisfied with a product, that doesn’t mean that a woman will be satisfied. But if a woman is satisfied with a product, a man is likely to also be satisfied.

Women Pay Attention to the Whole Experience, Not Just the Product

A whole user experience consists of many complex parts. It includes messaging and advertising, online experience, retail, packaging, first product use, storage, hundredth product use, customer service, and disposal. For women, all of these parts matter; they tend to judge the experience holistically. A product is only a fraction of the overall experience. To please women, companies need to consider and design the whole experience. However, this rarely happens. The root cause of this is that men tend to judge the product, not the whole user experience. They are more likely to overlook or forgive the bad parts of the whole experience and focus primarily on the quality of the product itself. In the male-dominated world of innovation, many companies reflect this mind-set and pour a disproportional part of their efforts into improving the product while paying less attention to the whole experience.

This approach frustrates women. If a woman has to spend several hours browsing a confusing company website, she will walk away before she has a chance to find out how good the product is. If she had an unpleasant warrantee experience, her overall feelings about the company will be negative, however outstanding the product might be. To make women happy, companies need to deliver a high-quality and cohesive whole experience. A good whole experience will also please men. Although men do prioritize, they still don’t like meaningless advertising, baffling websites, unopenable packaging, churlish salespeople, and indifferent service departments.

As designers, we often get project briefs from companies asking us to redesign a product. Quite often, we realize that this is not where the problem lies. We work with the client to redefine the project brief to include the design of the product and the design of whole experience. Our interdisciplinary team integrates needs from product to customer service to retail to brand; we design the whole customer experience.

For example, recently we were approached by a major car company—they were looking for ways to redesign their cars, making them more attractive for women. We found that although women had certain issues with the car design per se, the biggest challenges lay with the whole experience.

One of the primary questions we ended up with asking ourselves was, “Why is buying a $4 coffee in Starbucks a far better experience than buying a $30,000 car?”

First, it is difficult to research cars. Car company websites tend to describe the cars in terms best appreciated by car engineers and aficionados. Three out of the first five features describing the Nissan Versa are “Xtronic CVT,” “active grille shutter,” and “1.6L DOHC 4-cylinder engine.” To persuade consumers to buy the Chevy Cruze, the company has a large picture of “2.0L Turbocharged clean diesel engine” on the vehicle’s front page. The first thing that a prospective buyer learns about the Honda Crosstour is that its “new 3.5-liter i-VTEC V-6 engine delivers 278 hp and 252 lb-ft of torque.” What percentage of people will find this information relevant to their needs? Suppose that, in spite of this unwelcoming start, a woman learned from other sources that a Nissan Versa or Honda Crosstour or Chevy Cruze is a good car and decides to buy one. Then comes arguably the worst part of a woman’s experience. One of our users called it “car stealer-ships.” The overwhelming majority of women have very negative experiences with car dealerships. They can’t figure out what a fair price is for a car—Internet sources offer half a dozen different prices varying by as much as 10% to 15%. Women don’t like haggling; they feel cheated and ignored by car dealers. It’s so bad that most women try to bring a male friend or relative with them when they buy a car—they know that a man will get a better deal. After she passes the ordeal of buying a car, she drives it, she might have some issues with it, but generally she is not terribly unhappy. This is the high point of the whole experience. Then, the car breaks and she has to get it repaired. When the warranty runs out, the woman has to go to a repair shop. This experience is so frustrating that most women would rather delegate this unpleasant task to their male significant others. However, single women head 30% of American households and delegating is not an option for many of them.

If car companies are having such a hard time, why not innovate on the whole experience and improve women’s attitude toward them? If a car company made learning about and buying cars fun and interesting, instead of confusing and stressful, women would buy their cars. If a car company made it easy to take care of their cars, women would know that the company cares about them and would loyally return for their next car. Instead, many women use words “sleazy” and “disgusting” in describing their experience with the car industry.

It does not have to be this way, in the car industry or anywhere else. Recently a small company has been able to remove the “sleazy and disgusting” stigma from a much more questionable industry: the adult store. This small company’s adult stores deliver a satisfying whole experience. Ask anybody to imagine a typical adult store—it will be a small dirty place with a few creepy guys lurking around. In fact, it’s hard to imagine a place most women would less like to visit. At the same time, women and couples make up a large consumer segment of the adult toy industry. Enter Babeland (see Figure 13.3).

Screen comps © Aislinn Race/Website design © Babeland

Figure 13.3 Babeland website and marketing strategy.

If you visit their website, you will see a tasteful and well-organized space. The website aims to create a sense of community rather than just to sell products. Learning is fun through the blogs, videos, reviews by real people, and workshops. The message is clear: Here a woman can find a fun experience. The Babeland retail stores deliver the same message as the online space. They are clean, brightly colored, well lit, and spacious; they feel pleasant and safe. A woman can visit this store by herself, with friends, or with a partner and enjoy it. Each purchase comes with fun-to-read and informative care instructions written by Babeland. To sum it up, Babeland delivers a cohesive friendly and fun whole experience. The power of a great whole experience is that it’s able to transform an awkward product category into a shamelessly positive experience.

Women Want Real-Life Benefits, Not Potential Ones

Men and women perceive the relative value of potential and reality in products quite differently. Men tend to prioritize product potential—what a product is capable of—whereas women prioritize product reality—what they are going to do with a product. Potentially, a car can accelerate from 0 to 100 mph in four seconds; a camera can take 30MB picture for a wall-sized print; a TV can have facial recognition, voice control, and an Internet link to the refrigerator. But how relevant are these features in real life? What if a woman cares more that a car fits her two children, dog, and a cartload of groceries? What if she wants a camera that operates intuitively and does not need extra accessories to connect to a computer? What if she would rather have a TV that does not clash with her living room?

Often, companies, particularly in the consumer electronics and automotive industries, concentrate on potential—they find it more valuable and exciting. This approach drives technological innovation. Designers, engineers, and other technology fans constantly aim to improve product performance, particularly with respect to quantifiable specifications, like dpi, megabytes, gradation steps, and horsepower.

One of the reasons many women are unhappy with consumer electronics and cars is that they value reality more than potential. In the best-case scenario, both real-life and potential benefits should coexist in the product. However, if one needs to be sacrificed, women would rather see the potential benefits go. Since they don’t actually use it, the potential is less valuable to them. They choose simplicity, ease of operation, and other practical considerations over the ultimate potential.

Consumer electronics generously provides us with numerous examples that demonstrate the difference between potential and reality. Let us take a look at TVs and cameras.

If you walk into a Best Buy, you will see a long wall that carries several dozen TV sets that look identical, except for their size. To differentiate, the electronics companies invest an incredible amount of talent and effort to improve performance by a few percent. They are competing very hard on a narrow spectrum of easily quantifiable specifications. What if, instead, they took a closer look at what people, particularly women, want from a TV?

A major consumer electronics company asked us to find out what people wanted from a TV. We conducted ethnographic research on design-savvy women and couples. Our findings surprised the client quite a bit. Most women, and a large chunk of men, were less enticed by the electronic dream and more by the living reality. They didn’t care that a TV had 1% more resolution or that it was one-tenth of an inch thinner than its competitors. Instead, they cared about how it fit into their living rooms, how easy it was to install and operate, and how much effort it took to integrate the TV with their other devices.

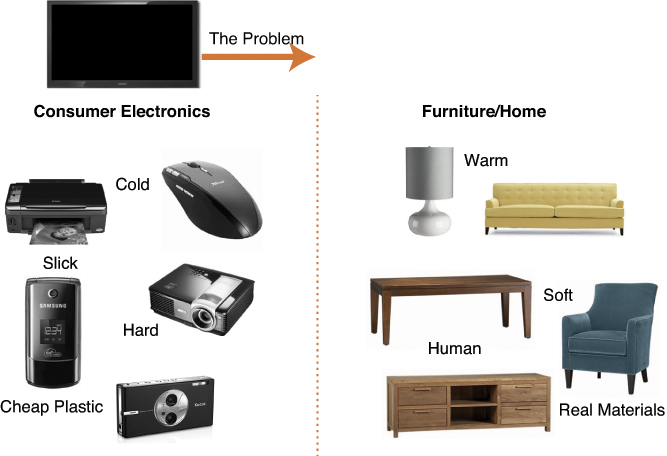

A woman doesn’t just buy a TV; she creates her home as a unique environment to reflect her taste and desires. The visual disconnect is depicted in Figure 13.4. Everything from a couch to a rug to the paint color should work together. A very large shiny black plastic box aesthetically fits perfectly into a Best Buy, but it doesn’t fit most home environments. One desperate woman painted a whole wall in her living room black in an attempt to make it work aesthetically. Another opted for all black furniture. Many just convince their husbands to buy smaller TVs so that they don’t stand out so much.

Mounting a TV is another major headache. Interior design magazines are full of photographs showing thin, flat TVs mounted on the walls and seamlessly integrated into the living space. People buy a flat TV only to discover that it’s either impossible or prohibitively expensive to mount it and to hide half a dozen cables in a wall.

The women complained about integrating the TVs with the other devices such as computers, cable boxes, speakers, DVD players, and other units. Interfacing these devices requires numerous cables and plug-ins that are often poorly marked. Each device is designed by a separate subdivision in a consumer electronics company. Each remote control to each device is designed by yet another subdivision. The engineers from the different groups often don’t interact and neither do their devices. This means that each remote control is unnecessarily complicated. A user has to invest significant time and effort into mastering interfaces that are not very intuitive. Men tend to fight their way through the process; some even enjoy the challenge. Women don’t see it as a challenge; rather, it is an annoyance and a distraction from other things that are important to them. All of it causes women to feel that the TV industry does not understand them and it does not address their real-life needs.

Video cameras tell a similar story. To understand how people decide which camera to buy, we spent a few hours observing shoppers in a Best Buy. Here, a couple of dozen of video cameras were attached with long cords to a table. A white card with specifications was attached next to each camera. Some people would start by reading the cards. The majority of people, particularly women, would pick up the cameras and start playing with them. A woman would turn on the camera, try to take pictures or videos, and play them back on the little screens. If she couldn’t figure out how to operate a camera in a few seconds, she would put it back on the stand and move to the next one. Our key conclusion is that despite whatever amazing technical performance a camera has to offer, a woman won’t buy it unless she can figure out how to use it in less than 30 seconds. And yet so many companies invest huge efforts in boosting performance while sacrificing this first interaction. A common innovation pitfall is getting excited about a “cool” new technological feature and deciding to highlight it. The problem is that most of the time these “cool” features are potential benefits, not real-life ones. The digital interfaces become needlessly cluttered, frustrating, and difficult to operate, exasperating users away.

GoPro chose an opposite approach. Instead of coming with more “cool features,” they identified an important real-life need that was not addressed by the video world. Then, they created a device precisely to fill this niche, to make action videos of extreme sports. They concentrated on delivering real-life benefits—how to enable users to take good-quality videos under real conditions from underwater to a snowstorm. They built a small rugged camera with a very simple interface that can be operated blindly in winter gloves. They designed a variety of reliable and practical attachments that enable users to fix the camera to a head, a helmet, a snowboard, a kayak, or a car. Interestingly, by offering real-life benefits instead of potential ones, GoPro conquered a young and mostly male customer base—extreme sport fans. But, as the general public realized the advantages of the cameras, the GoPro camcorders flooded the market; everybody wanted to easily record exciting moments in their lives. Now, the ubiquitous little boxes are everywhere and they are used by children, men, and women alike. The GoPro website also shows a shift in their consumer base—their large collection of videos starts with extreme sports and ends with a mother recording her 6-year-old son’s first ski turns. Even under the guise of extreme sports, women recognize and are happy to adopt the real-life benefits of the GoPro.

Women Appreciate Human Traits in Objects

This broad-thinking topic is the most difficult to describe, quantify, or measure. Many designers either are not aware of it or underestimate its significance. Based on many years of successfully designing products for women, we’ve learned that a woman can connect to products on an emotional level and that she is more likely to connect when the product possesses human traits and has an attractive personality.

Scientific studies (and our own design experience) demonstrate that women are better at observing, understanding, and relating to other people, whereas men are more comfortable with machines.

In one experiment, Diane McGuinness and John Symonds showed pairs of images of humans and mechanical objects, using a stereoscope, to men and women. The two images fall on the same part of the visual field and compete for attention. The women reported seeing more people and the men saw more machines. The Profile of Nonverbal Sensitivity (PONS) Test was developed in 1979 and has been studied in multiple experiments in the decades since. These studies have shown that women are significantly more sensitive to facial expressions than men. This gender difference holds up in areas as varied as New Guinea, Israel, Australia, and North America. Ruben and Raquel Gur, neuroscientists from the University of Pennsylvania, conducted experiments with Brain MRIs and found that women are capable of recognizing a facial expression before men even recognize it to be a face. Jennifer Connellan and Anna Ba’tki from the Autism Research Centre at Cambridge University ran an experiment in which they found one-day-old girls spend more time looking at faces whereas one-day-old boys spent more time looking at mobiles. And it doesn’t stop at humans. Melissa Hines of City University of London and Gerianne Alexander of Texas A&M University gave a large variety of toys to a group of baby velvet monkeys; girls preferred dolls, boys preferred cars and balls, and everybody equally liked stuffed dogs and picture books.

As designers, we have regularly observed similar preferences in our field. Women are instantly drawn toward products that project human traits, something they can relate to. They often see distinct personalities in products. At a first glance, a woman will see that a car is aggressive, a TV is boring, and a chair is cute. If a woman thinks that a product has a boring or unpleasant personality, she is far less likely to want it in her life.

Designers are very well aware that any product projects an image. They work hard on object aesthetics and they might aim to make their product look sleek, expensive, powerful, or rugged. They try to design products that project an image of a desirable product. But this is not enough. A woman might notice when a product looks sleek, expensive, powerful, or rugged. But she might not emotionally connect with it. To win her heart, the product needs desirable human traits.

One of the tools that we use to identify human traits is this set of questions: “What type of person would this object be? What gender would they be? What would be their hobbies and work? What car would they drive? Who would their friends be?”

Women pick up this game immediately and enthusiastically. It is surprising how similarly women describe an object. If a woman says that the person inside the object is boring and doesn’t have much personality, it’s like a kiss of death. If a woman finds that an object has an attractive personality, she immediately gets excited; she is likely to like the product more and to be more forgiving of any technical faults.

Breakup and love letters are another tool that we commonly use. This tool demonstrates how this personalization extends beyond the product to the whole experience. We ask women to write a breakup or love letter to a product as if it were a real person. They write touching and funny personal letters to TVs, cellphones, bras, and cars. They use such words and expressions as “cheat,” “love of my life,” “I’ve been having an affair,” “disappointed,” and “love at first glance.” We have found two points particularly important: It is a natural thing to do for all women, and everybody goes past the purely product experience and includes the whole experience.

This exercise has been integrated into the Philadelphia University core curriculum. In the “Glossary and Resources,” we offer links to one of the more amusing videos of this.

Advantageously for designers, human and object traits are not mutually exclusive in any way. A truly successful design is able to combine both object and human traits in a harmonious way. Then, both men and women can easily connect to the product. The most successful products manage to project different but equally positive images to both men and women.

Men describe the Mini Cooper as a former stunt car, with a large engine and a prominent air intake, and women describe the same car as their “friendly little sidekick.” The Mini Cooper, Fiat 500, HP Photosmart printer, Flip videocamera, and Method soap are very different products that are united by one design consideration: They have distinct personalities. On the other hand, the Toyota Corolla (see Figure 13.5), Panasonic TX-37LX75M 37-inch TV, and HP LaserJet Pro P1102w laser printer need a personality infusion.

Human traits are what make women look at this product and smile. This smile-generating capability might be difficult to measure and quantify. Nevertheless, it is key to designing for women.

Conclusions and Recommendations

In this chapter, we demonstrated how to design for women. Creating products and services for women is a challenging task that has confounded many talented designers. It has been a source of hard work and great satisfaction for my colleagues and me. Eventually, we found that truly interdisciplinary broad thinking is necessary to successfully identify, address, and solve the challenge. The main difference between men and women is that women have more angles, needs, and requirements than men do. A great solution has to address it all.

A good design will consider the needs of “we.” A successful product will be only a part of the enjoyable whole experience. Every stage of the experience—from marketing to retail to packaging to use to customer service to storage to disposal—needs to be considered by an interdisciplinary design team. The design team must addresses a woman’s real-life needs and design a product with a personality that she likes and relates to; then, a woman will be truly satisfied with not only the product but also the brand. She will know that the company likes her, understands her, and addresses her needs. A woman will forge a personal relationship with the brand and she will become loyal to it. Here comes the good news for the company: It will be a faithful, long-term relationship.