16. Opportunities in Branding—Benefits of Cross-Functional Collaboration in Driving Identity

Maryann Finiw has more than 20 years of experience managing innovation, research, and strategy programs. She is currently Senior Manager of Research and Marketing Strategy at SapientNitro and is also an Adjunct Professor at Philadelphia University, Emerson College, and Massachusetts College of Art and Design. In her previous position as a Principal at Continuum, she led innovation strategy projects for major corporate clients, including Ford Motor Company, Procter & Gamble, Coca-Cola, Andersen Windows, Master Lock, L.L.Bean, and American Express. With an M.B.A. from Harvard Business School and a Bachelor of Industrial Design from Pratt Institute, she thrives at the intersection of design and business; research and development; creativity and strategy.

Context

I began my education and career as an industrial designer, gaining experience in a field where the benefits of cross-functional teams for product innovation are now well known. Marketers, designers, and engineers working together on interdisciplinary teams have become the norm in new product development. In my professional evolution as a branding consultant and as a professor, I’ve found that applying those design-thinking principles and collaborative best practices to branding endeavors drives disruptive innovation and enables superior outcomes from the brand strategy process.

Why Use Innovation Teams? Four Key Benefits for Branding

Using truly collaborative teams that incorporate design thinking into their process can create brand strategies that are more relevant, holistic, impactful, and actionable. I call these cross-disciplinary collaborators innovation teams. To illustrate the effectiveness of this approach, I’ll share real-world case studies, my personal experiences, and interviews with key project collaborators that will reveal why these interdisciplinary teams create better brand strategies. I’ll include process examples that highlight some of the innovative methods that made these projects successful in order to illustrate how well-managed teams can create brands that consumers love, build brand loyalty, and increase profits.

More Holistic

Innovation teams create brand propositions that are more holistic and have a broader appeal

Market segmentation is a primary tool used by marketers. To create a sound brand strategy, marketers identify multiple customer segments within a market, select the segments to target, and then seek an understanding as to how their particular brand can uniquely meet the needs of, and resonate with, those specific customer groups. A common challenge that marketers face is how to speak to each segment without alienating the members of other segments. In companies that employ a more functionally siloed process, the segment and competitive perspective might also be more siloed and is likely to fail to elicit more innovative strategies. An interdisciplinary approach to brand strategy can uniquely facilitate identifying the glue that unifies one brand to meet the needs of seemingly disparate segments.

Employing a familiar term, a traditionally siloed marketing process employs a “left-brain” perspective. Left-brain thinking is seen as being primarily calculative—one plus two equals three—whereas right-brain thinking is considered to be more holistic—it sees the answer three and doesn’t care whether it was derived from one plus two, four minus one, or nine divided by three. In the past, a more functionally siloed brand strategy process would often fail to find the solution to making the entire brand greater than the sum of its parts because of its basis in quantitative analysis. By involving interdisciplinary teams in a brand strategy program, we can employ a “whole-brained” and holistic perspective, an approach that has become known as “design thinking.” Design thinking resolves the seemingly conflicting needs of diverse market segments to create a holistic brand image. By using interdisciplinary teams, we create a creative-process ecosystem that encourages and engages whole-brain thinking and enables the team to see the entirety of the brand value proposition.

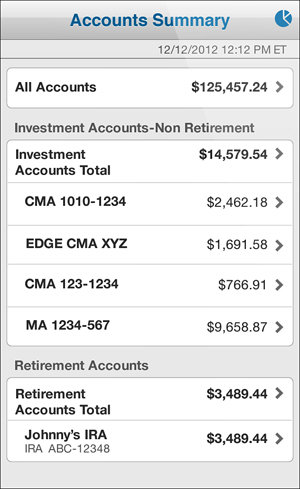

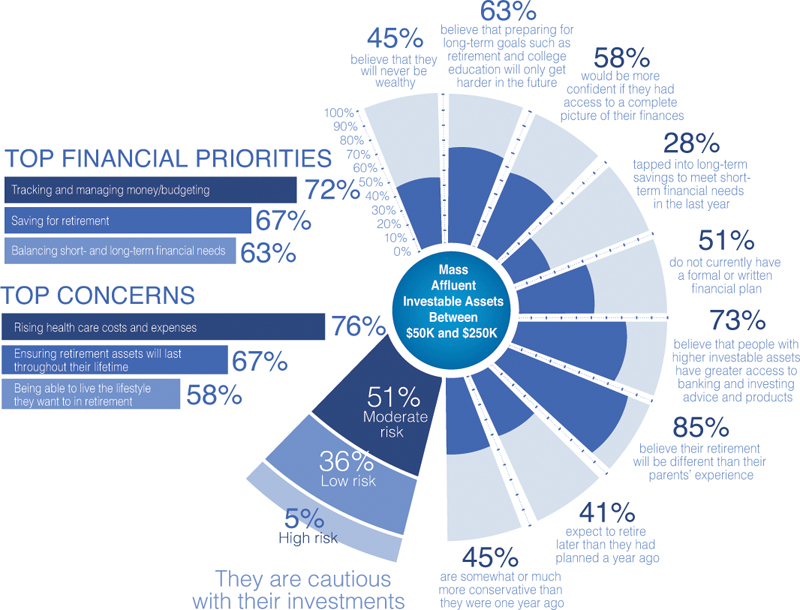

An example of a design-thinking approach to brand strategy is illustrated in the launch of Merrill Edge. Merrill Lynch is the world’s largest investment brokerage, with more than 15,000 financial advisors and $2.2 trillion in client assets.1 Bank of America is the second-largest bank holding company in the U.S. by assets, operating in all 50 states and in more than 40 countries around the globe.2 The merger of Bank of America and Merrill Lynch in January of 2009 created an opportunity for these two financial powerhouses to offer an integrated and uniquely powerful banking and investing capability. Complementing the Merrill Lynch Wealth Management business that serves affluent and high-net-worth individuals, there was an opportunity to broaden access to integrated banking and investing solutions for the next generation of affluent individuals, the mass affluent consumer. As shown in Figure 16.1, mass affluent is a marketing term that refers to investors who have household incomes over $75,000 per year and $50,000 to $250,000 in investable assets. The challenge for the cross-functional team developing the new integrated banking and investing solution from Bank of America/Merrill Lynch was how to appropriately marry the combined brand equities brought to the mass affluent target consumer by Bank of America and Merrill Lynch without alienating core Merrill Lynch Wealth Management clients.

http://newsroom.bankofamerica.com/files/press_kit/additional/WhoAreTheMassAffluent012411.pdf

Image courtesy of Bank of America Merrill Lynch.

Figure 16.1 Who are the mass affluent?

The team that developed the Merrill Edge name and offering included product, platform, and marketing representatives from Merrill Lynch and Bank of America, and from third-party agencies in strategy, branding, and digital design. My role was to focus on customer insights and innovation strategy as an embedded consultant on the internal team at Bank of America. Besides the typical challenges of managing an interdisciplinary team, this team faced additional integration challenges. Since the merger between Bank of America and Merrill Lynch was new, the team had to forge working relationships between two formerly separate corporate cultures. Additionally, because banking and investing are both highly regulated industries (each operating under different sets of rules), legal and compliance experts were also integral to the team.

Tony Hitchman, SVP, Head of Merrill Edge Marketing at Bank of America Merrill Lynch, describes the critical glue that would unify these disparate perspectives as, “Be true to the clients.” Our challenge was to balance the needs of the mass affluent prospects—for an offering that did not yet exist—against the brand perceptions of core Bank of America and Merrill Lynch clients. Our interdisciplinary team conducted multiple rounds of research with these diverse client constituencies to identify opportunities for naming, positioning, and differentiation.

The resulting name, Merrill Edge, successfully balances the equities of Bank of America and Merrill Lynch in ways that resonated with both client segments. Launched in 2010 on the heels of the 2008 financial service industry crisis, Merrill Edge was given important stability by Bank of America, so as shown in Figure 16.2, we used “Bank of America Corporation” in the logo as a visual foundational baseline. “Merrill” brought important investing credibility to the offering, but for the mass affluent customer, the full name of “Merrill Lynch Wealth Management” was perceived as being for someone wealthier than a member of the target demographic. To appeal to a more youthful mass affluent demographic, the name “Edge” was created to express an offering that was younger, hipper, and cooler. Merrill Edge was not their parents’ Merrill Lynch solution. For the core Merrill Lynch Wealth Management client, the word “Edge” reassured them that this was a new offering from the company that wouldn’t jeopardize their brand relationship with Merrill Lynch Wealth Management. As SVP Tony Hitchman explains, “Merrill Edge unites the banking strength of Bank of America with the insights of Merrill Lynch.”

By creating an integrated team that enlisted multiple disciplines across several agencies and that spanned the newly merged companies, Merrill Edge delivers a value proposition that is holistic and has broad appeal. As illustrated in the mobile app shown in Figure 16.3, Merrill Edge offers the ability to easily move money between banking and investing in one online platform and includes available investment guidance. As Justine Metz, head of Global Wealth Management Marketing at Bank of America, explains, “The potential benefits to the customer and the business, of providing better solutions to the client, far outweigh the team integration challenges. It may take longer, but you get to a better result.”

Merrill Edge successfully launched in June 2010 and continues to grow, both in customer awareness and in number of accounts added. By July 2013, Merrill Edge had more than 1.5 million accounts and over $87 billion in brokerage assets. The awareness of Merrill Edge has seen double-digit percentage increases each year from 2011 to 2013, adding to the brand’s potential growth.

More Relevant

Innovation teams help make brands more relevant to consumers by connecting on deeper values

In the preceding example, we discussed how teams can identify the glue that unifies one brand and leverage it to meet the needs of seemingly disparate market segments. Another key benefit of using interdisciplinary teams for branding is their ability to uncover and identify the glue that bonds consumers to a brand. Truly collaborative teams are better at identifying and embodying the brand core values that connect with consumers at multiple levels: functionally, emotionally, and culturally. By focusing on deeper brand values, they can build deep-seated brand loyalty.

Brand loyalty is strong when consumers are aware that some of the values they hold most dearly are shared by a brand whose products they buy. Examples of these brand values are the triple bottom line commitments at companies like Ben & Jerry’s or Newman’s Own. Having corporate values in common with values held by your customers is the ultimate glue that bonds a consumer to a brand. As Simon Sinek proposes in his TED Talk on “How Great Leaders Inspire Action,” “People don’t buy what you do; people buy why you do it—your purpose, your belief.”

L.L.Bean is one of the nation’s most respected and best-known manufacturers and distributors of outdoor clothing and equipment. L.L.Bean is headquartered in Freeport, Maine, and its legendary flagship store, shown in Figure 16.4, has no locks on the entry doors, since it is open 24 hours a day, all year long. As an outdoor lifestyle brand, L.L.Bean’s product lines and customers range from outdoor equipment for serious enthusiasts engaged in hunting and fishing, to selling, at the other end of the spectrum, outdoorsy home goods and apparel that are more likely to be used in backyards than in the backwoods. In a previous brand strategy project sponsored by L.L.Bean, a traditionally siloed brand consulting firm had recommended that L.L Bean split the company into two brands: one brand focused on equipment that would compete against companies like REI and North Face, and another brand focused on apparel that would compete against companies like Gap and Polo. L.L.Bean wisely rejected this recommendation, instinctively understanding that these seemingly incompatible segments had coexisted for almost a century within one of the most beloved companies in America. Its unifying brand attributes—although difficult to articulate—had given L.L.Bean a track record of deep consumer loyalty and unparalleled business longevity.

In 2005, as a Principal in the Design Strategy Group at Continuum, I led a project team tasked with the dual goals of understanding L.L.Bean’s deep brand heritage and identifying how to leverage its brand legacy and iconic products in ways that would be relevant to today’s consumers. We called it Project DNA. The internal core team for L.L.Bean’s brand DNA project included a diagonal slice across a matrix of disciplines and management levels from both the client and Continuum. We drew team members from middle to senior management, and from marketing, strategy, merchandising, product design, and communications design groups. Consequently, the most important stakeholders at L.L.Bean all had their interests represented. Beyond their involvement in the brand DNA project team, they were ultimately responsible for embodying the brand in the design and merchandising of products. When L.L.Bean used this highly collaborative interdisciplinary team to help articulate and leverage its brand heritage, they were able to find the common threads that strongly connected the brand to both the devout outdoor sportsmen and the casual outdoor apparel consumers.

In direct contradiction to the traditional branding firm’s previous attempt to split the company into “backyards” and “deep woods” market segments, our team was able to identify 16 shared values that emotionally connected the brand to both of those seemingly disparate segments within L.L.Bean’s customer base. For example, one of the shared values we identified is “reliable.” The L.L.Bean brand is valued as “reliable” across all varied segments, but the “reliable” brand attribute gets embodied differently to meet the needs of each segment. An outdoor enthusiast can rely on L.L.Bean’s outdoor equipment to keep them safe and warm even in harsh outdoor conditions, and an apparel customer can rely on L.L.Bean clothing to not fade, even after repeated washings. The company also reinforces reliability with its legendary 100% satisfaction guarantee.

By the end of the brand DNA project, we had provided L.L.Bean with a powerful tool. As Marcia Minter, VP Creative Director at L.L.Bean describes, “These are not just product attributes or brand values; they’re our corporate values. They’re what the company is all about—how we do things and why we do it.” Marcia says the level of clarity provided by these brand values is broadly applied within the company, and she routinely shares the core brand values with L.L.Bean’s outside collaborators—from large firms to individual contributors, and advertising agencies, design firms, and photo stylists. Marcia even refers to these values in job interviews and on a new hire’s first day. Minter concludes, “It fundamentally comes down to already having a moral position on how to engage with people.”

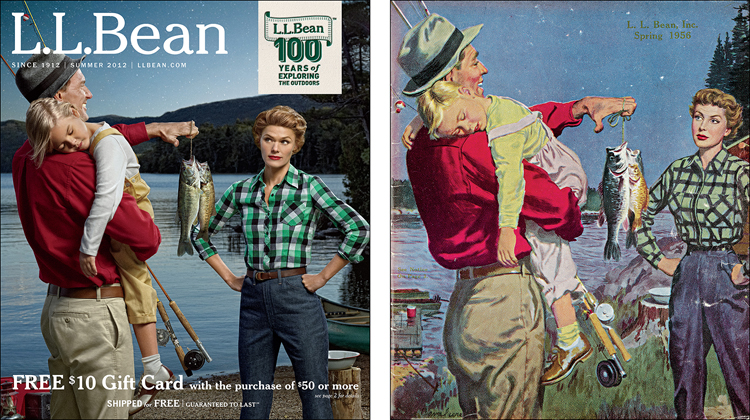

In 2012, L.L.Bean celebrated its centennial anniversary, a significant milestone in the life of a brand whose values continue to resonate with its diverse consumer segments. As illustrated in Figure 16.5, L.L.Bean reinterpreted some of the iconic catalog covers that helped define the company’s unique character to help commemorate this important anniversary. As Tom Armstrong, CMO of L.L.Bean, explains, “These shared values are customer-relevant and timeless. They ground us and act as a foundational touchstone that orients people to who we are.”

More Impactful

Innovation teams achieve superior business results by identifying more meaningful brand differentiation

Teams help achieve superior results for both the end user and the business. The multiple perspectives help identify meaningful attributes on which to differentiate that are more relevant to consumers and more impactful to the business. Emily Bowden, Brand Strategist at Sapient Nitro, explains it best: “Where mere cross-functional connections can be effective in working towards a common goal, a truly collaborative process invites disruptive innovation.”

Some of the world’s strongest brands offer iconic products that would be recognized if even a fragment of that product were found by an archaeologist. Any industrial designer dreams of his professional legacy containing a product as iconic as Coca-Cola’s bottle, Apple’s iPod, L.L.Bean’s Maine Hunting Shoe, or Master Lock’s laminated padlock. Master Lock’s laminated padlock is so iconic that a graphic abstraction of a laminated lock is used as an onscreen symbol by many software developers to indicate whether a file is locked. Master Lock’s laminated padlock is one of the most successful products in history, though the patents on the laminated padlocks expired decades ago. In the mid-1990s, Master Lock was not innovating. Widely recalled for its Tough Under Fire “shot lock” commercials, as shown in Figure 16.6, the Master Lock name elicits an enviable 98% unaided brand awareness, but in the mid-1990s that brand recognition was not translating into sales, so mass merchant retailers were threatening to reduce Master Lock’s shelf space allocation. In addition, Master Lock wasn’t doing a good job of differentiating its products; mass merchant shoppers no longer perceived the added value of the Master Lock brand compared to the cheap Asian knockoffs displayed on the same shelves.

Traditional management consultants recommended that Master Lock had no choice but to compete on price in what was becoming a commodity market. John Heppner, CMO at the time (now CEO), rejected this recommendation and decided to employ an innovative design-thinking approach to identify differentiation opportunities that would allow the company to continue to command a premium market position and preserve shelf space. As a Principal at Continuum, I led the research and strategy project for Master Lock’s innovation and differentiation initiative.

Heppner summarizes his philosophy about investing in capacity-building and focusing on growing innovation capability: “It’s all about how you use the consulting relationship, whether you are expecting an answer from them, or using them as input, collaborating with them. Way too many just ask for the answer, but the company’s got to execute, so I want to learn what I don’t know. If you just delegate to consultants as a crutch, it falls apart. It’s an investment to gain a competency.”

During its previous product development programs, Master Lock had used a siloed research approach that primarily focused on getting feedback from locksmiths. To innovate on meaningful attributes, Master Lock needed to understand what mass merchant shoppers valued when shopping for padlocks. At mass merchants, it was particularly important to understand what women shoppers valued when shopping for security products, since 72% of shopping trips to mass merchandisers are made by women.3 Consistent with Yvonne Lin’s findings in Chapter 13, “Broad Thinking—Connecting Design and Innovation with What Women Want,” women, as the main purchasers of consumer products, care more about what a product or service will do for them and their families than they care about the technical features offered. Consequently, the multidisciplinary team needed to understand what would motivate women at Walmart to choose a Master Lock padlock over a cheap Asian knockoff. During ethnographic in-store shop-a-longs with consumers at mass merchants, our team experienced a key “ah-ha moment.” We discovered that shoppers expected bike locks to be in the bike aisle and luggage locks to be in the luggage aisle, but Master Lock’s padlocks were (at the time) merchandised exclusively in the hardware aisle. People are not emotionally connected to padlocks; they are emotionally connected to what they want to protect. This key consumer insight translated into a market segmentation plan and channel strategy for Master Lock that showed them how to look “beyond hardware” and broaden distribution beyond the hardware aisle and hardware store. A collateral piece from this segmentation plan is shown in Figure 16.7. The company even used “Beyond Hardware” as a campaign theme for Master Lock’s booth at that year’s annual industry trade show.

The new differentiation strategy created significant business growth opportunities. With innovative new designs targeting key users and applications, Master Lock successfully gained distribution not only in new aisles, but also in new channels such as Target, Pep Boys, and AutoZone. Heppner clarifies, “One of the ancillary benefits we achieved in looking ‘Beyond Hardware’ was the ability to better understand the full extendibility of our brand—where it could potentially play and be successful. The segmentation exercise, combined with ultimate acceptance of the brand outside hardware, provided not only a stronger foundation for organic growth, but also strategic direction for where we might make acquisitions and utilize the brand as a key differentiator in an underrepresented segment or category.”

More Actionable

Innovation teams gain greater consensus and buy-in from the client

The diversity of talent in interdisciplinary teams generates creative energy that fosters actionable brand strategies. These teams help gain stronger consensus, because they can offer a more richly layered set of reasons to support a position. Strategic directions are pressure-tested against multiple perspectives to manage trade-offs and reach compromises that create the strongest total system design. Core team members become evangelists throughout the client organization so that functional peers see that their perspectives were anticipated and addressed for greater buy-in and smoother implementation.

For Master Lock, the extended team even collaborated with retailers. Traditionally, if a product failed, retailers were stuck with liquidating inventory, so retailers might have been hesitant to embrace the innovative products and differentiation strategy that Master Lock was proposing. Master Lock reorganized its sales organization around the new segments, since it would be calling on buyers “Beyond Hardware.” Master Lock then previewed prototypes with retailers to bring in its point-of-sale perspective and tested sales by rolling out new products to a hundred stores to evaluate their success before executing nationwide.

If the category was becoming commoditized, Master Lock, as the category leader, wanted to lead the fix of the entire category. The goal was to change retailers’ brand perception—to see Master Lock as a fresh, innovative partner. Heppner explains the strategy: “Being first is good for the brand. Now, we continuously bring freshness to the brand with so many new products that customers turn some down, but then they don’t look elsewhere. That adds strength to the brand.”

Leveraging the foundational work of this innovation team, Master Lock has launched a steady stream of innovative new products that are selling well and winning awards. Master Lock’s Titanium series of padlocks was one of the first products launched from the product road map we envisioned. The Titanium series of padlocks, shown in Figure 16.8, won recognition in Business Week magazine’s annual Industrial Design Excellence Awards with a Gold IDEA in 2002 for product design and in 2007 as a finalist for a Catalyst IDEA, a competition that recognizes a product design’s impact on market success and business transformation. The CEO of Master Lock tied its sales goals to the project innovation goals with the objective of reaching 25% of current-year total sales to be generated by products introduced over the previous three years. Master Lock now consistently exceeds that 25% new product sales metric with a continuous stream of award-winning innovative new product launches, such as the Speed Dial combination padlock that won a silver Edison Award in 2011.

How to Drive Innovation Teams: Process Best Practices for Branding

The previous case studies have illustrated why interdisciplinary teams are better at achieving brand innovation. These teams create brand strategies that are more holistic, relevant, actionable, and impactful while generating meaningful results for both customers and the bottom line. It’s important now to share some of the behind-the-scenes details of the processes that made these project teams so successful.

Convene a matrixed team composition: The most effective cross-functional teams are taken from a “diagonal slice” through the management chart of the organization, and should include younger managers with fresher perspectives, as well as people with a greater stakeholder position who can execute on initiatives downstream. If possible, teams should include critical consumer and customer/retailer perspectives as well. As Mike Arney, Principal at Continuum, explains, “The challenge is to get people to live at both altitudes; to represent their function, and also to rise above it.”

Recruit pairs of research respondents: To evoke deeper and more interesting insights during the research phase, recruit teams of research respondents in pairs, such as couples or best friends. Conducting in-context ethnographic interviews with pairs of respondents elicits a more natural dialogue. These participant pairs keep each other honest and build on each other’s comments, guiding the conversations toward identifying a brand’s most significant emotional connections to the user. For our outdoor lifestyle brand research, we even included recruits from multiple generations of families. They gave us a layered perspective on interactions with the L.L.Bean brand, from holiday gift giving to using the brand’s outdoor equipment on family vacations.

Use immersive research techniques: Nothing is less interesting for a research subject than being shown pictures of products while seated at a table in a windowless office building. During our L.L.Bean consumer research phase, our team conducted immersive activities with research subjects that were often done either at the subject’s home or at a family cottage on a lake. We demonstrated tactile product interactions in a context designed to vividly express the core L.L.Bean brand values that consumers love, while tapping into memories and evoking stories that would elicit deeper insights into the unique qualities of the brand.

Create an immersive team space: Provide a dedicated war room that is a casual yet compelling environment that will help move the project forward. Office cubicles and conference rooms maintain hierarchy and status quo, but when people interact in a more casual environment, like a kitchen, a living room, or at the proverbial water cooler, they’re relaxed and more likely to exchange and embrace different perspectives. The immersive environment should also be an inviting space where team members can come to work and think critically about the project.

The L.L.Bean team created an immersive project war room that we called “Base Camp.” The goal was to “live” the brand and immerse ourselves in an outdoor lifestyle so that when we met as a team we would be closer to the mind-set of the outdoor enthusiast consumer. As shown in Figure 16.9, to immerse ourselves in the brand heritage, we surrounded ourselves with antique products and catalogs and collected the personal stories from sellers on eBay who were auctioning off their well-worn L.L.Bean heirlooms. The Base Camp war room was so effective a tool for collaborative meetings that when it came time to socialize the brand values and launch the training process throughout the L.L.Bean organization, the company moved the contents of the war room, as shown in Figure 16.10, from Newton, Massachusetts, to the Freeport, Maine, headquarters.

Photo courtesy of L.L.Bean.

Figure 16.10 L.L.Bean war room: a blend of archaeology and anthropology.

Prototype strategy: Prototyping isn’t just for products—it should also be used to envision, visualize, and test the entire brand strategy. Create experiential models so that you can simulate and evaluate the user experience. Incorporating prototyping into the brand development process improves quality and focus. As illustrated in Chapters 9, “Navigating Spaces—Tools for Discovery,” and 10, “Value Creation through Shaping Opportunity—The Business Model,” a key element of the design-thinking process is prototyping. In a traditional business process, people are rewarded for success, whereas prototyping, by definition, expects failure again and again until the design direction and details are fully vetted. It is important to note the difference between mistake and failure. Mistake is an error disconnected from theory. A failure includes theory. Each failure then represents learning, or “failing forward.” Prototypes are iterations in a design process that provide learning moments that improve results. Evaluation of prototypes focuses criticism on the prototype, not on individuals, so that all team members can align on making the best strategy for the consumer and build on each other’s ideas. When critiquing prototypes, team members are not in it for themselves; they are, ideally, advocates for the end user.

Master Lock and Continuum’s multidimensional team prototyped a ten-year road map for the product and package designs, and also envisioned what the business would look like if it pursued the market segmentation and channel strategy opportunities identified to move “Beyond Hardware.” Master Lock then enlarged the road map in order to refine and update product development and launch plans for each target segment and retail channel, and to make the segmentation strategy road map an actionable living prototype.

Encourage healthy debate: Foster true collaboration among team members by promoting vigorous, healthy debate. Debate pressure-tests ideas, exposing and resolving conflicts; it also creates a better experience for the end user and drives better outcomes for business. To refocus attention away from disparaging a teammate’s ideas and onto improving the user experience, direct the debate toward customer needs, data (including soft data such as consumer anecdotes and stories), and evaluating and improving prototypes.

Heppner explains, “Collaboration is a very intense exercise to get to the ‘ah-ha’ experience. It’s the rigor of the process to constantly iterate, honestly talk through issues, and collaboratively work through them together. People think and express themselves in different and unique ways. To get the full value of that input, you need to create creative tension. Not every team member contributes at the same level at first—you must yell, offend, and take no prisoners to achieve total collaboration and best thinking.”

Conclusions and Recommendations

This chapter examined several real-world case studies in which cross-functional teams developed powerful brand strategies for a range of industries, from outdoor apparel and security devices to financial services. A truly collaborative team can create a brand strategy that is more holistic, relevant, and actionable, offering more meaningful results for customers and improving a company’s financial health. We consistently saw these benefits across a range of brand challenges, from launching a new brand offering to articulating and leveraging the core DNA of existing brands. The reader is encouraged to recognize and leverage the unique capability of cross-functional teams and apply the process tips for effectively managing collaborative teams in a brand strategy program. The result can be the creation of a stronger brand that consumers will love, with increased brand loyalty and greater company profits. Specifically, in summary:

Why to Use Innovation Teams: Four Key Benefits of Teams for Branding

• More holistic

• More relevant

• More actionable

• More impactful

How to Drive Innovation Teams: Process Best Practices for Branding

• Convene a matrixed team composition

• Recruit pairs of research respondents

• Create immersive spaces and activities

• Prototype strategy

• Encourage healthy debate

Endnotes

1. Wikipedia, Merrill Lynch size.

2. Wikipedia, Bank of America size.

3. Nielsen, Share of U.S. Retail Channel Shopping Trips by Gender, 2012.