CHAPTER SEVEN

THE CHALLENGE IN MEASURING CUSTOMER EMOTIONS

Successful organizations understand that quantitative feedback concerning customer judgments about service quality is essential for assessing whether customer needs are being met. Recent and improved technologies have made it relatively easy to measure tangible indices such as telephone hold times, the number of times a customer calls, numbers of abandoned calls, average talk times, and so on. However, because emotions also affect customers’ judgments, it would be advantageous to measure and understand their strength in the service equation.

Unfortunately, customer emotional indicators are difficult to quantify and measure. Consider the examples in column 2 in the following chart:

122

Obviously, it is a better idea to measure important customer data than to measure less important business data. Unfortunately, because column 2 factors are difficult to measure, even though they are important, companies tend to have limited data on these metrics. You may also note that they are primarily emotional in nature.

What are the behavioral implications connected to feeling pride in purchased products or services?

Marsha Richins, professor of marketing at the University of Missouri, after summarizing the literature on customer emotion measurements, states point-blank, “At present, consumer behavior scholars have scant information about the nature of emotions in the consumption environment or how best to measure them.”1 She believes that it would be useful, for example, to know “exactly what it means to feel pride in product ownership, the conditions that create feelings of pride, and the effects of these feelings on other consumer variables such as brand loyalty and word of mouth.”2 These are important factors and yet are not easy to quantify or evaluate.

123

Assessing the Emotional Reactions of Customers: The Obstacles

There are four challenges to assessing full customer reactions to service:

- Time

- Capturing customers’ overall assessments

- Proving results

- Defining satisfaction in the minds of customers

The first challenge of time is easy to describe, but it is, nonetheless, a huge obstacle. Fully understanding customer emotional reactions can require in-depth interviews requiring significant time to administer. These interviews also have to be scored and analyzed.

A second challenge is capturing the overall assessment of customers’ experiences. Customers tend to mentally evaluate service experiences as a whole, while few research approaches are capable of accurately capturing the total experience of the customer.3 Surveys are better at measuring component pieces of the service process. William Thomas, national director of human resources for Coopers and Lybrand, identifies the challenge in capturing the concerns that serve as the foundation for long-term customer relationships:

Real satisfaction, however, is based on much deeper values, which are developed and nurtured by ongoing relationships and experiences between a company and its customers. It is extremely difficult, if not impossible, to truly measure the degree to which customers’ experience of a product or service over time matches their dynamic expectations unless the customer is engaged in a way that transcends temporal customer-satisfaction surveys.4

Instead, what we get are measurements on survey forms, such as “perceives front desk clerks as polite” or “thinks medical staff cares for patients.” Marketing Professor Linda Price, at the University of South Florida, sees these types of measurements as “simplistic” indicators of how service providers are performing their jobs.5 Customers who have ever filled out such questionnaires do not need to be told by academic 124researchers that these measurements are inadequate. The authors’ experience is that every time we have been surveyed, only a small slice of our feelings about the service we just experienced was being reviewed.

The American Management Association cites research in which executives across the United States were asked what business measurements are most important to them. The executives listed financial performance, operating efficiency, customer satisfaction, employee performance, innovation/change, and community/environmental issues. Of these metrics, customer satisfaction was chosen as being of most value by the largest percentage of the executives surveyed. But how confident were the corporate executives in the data they received from their staff about customer satisfaction? Very few of them trusted it.6 We would agree that their skepticism is justified.

Most executives don’t have any proof that implemented customer satisfaction efforts have added economic value.

A related study by the Juran Institute, the consulting firm founded by quality guru Joseph M. Juran in 1975, suggests that less than 30 percent of executives have any concrete proof that implemented customer satisfaction efforts have added economic value to their bottom lines. Only 2 percent (Yes, that is correct—2 percent!) were able to precisely measure the bottom-line impact of improved customer satisfaction levels.7 Yet in a survey conducted by Minneapolis-based human resources consulting group Towers Perrin, 90 percent of executives agreed that if they could improve employee customer service performance, it would improve bottom-line results. These executives also recognize the role of staff in their overall business success: 73 percent said that their staffs were their most important investment.8

The reason why so few companies have proof that customer service programs impact economic results is that they are difficult to scientifically prove. Research on the impact of employee customer service training on customer retention exists, but most of the results point to indirect connections. Ryder Truck Rental, for example, found that employees 125who attended training programs had a 19 percent turnover rate; for the untrained employees, the rate was 41 percent. Based on other research, it is reasonable to conclude that if staff remain in their service positions longer, then better customer service is offered. But drawing direct cause-and-effect links is problematic.

In a more tightly controlled case study of a New England utility company, researcher Rosanne D’Ausilio found that after a four-hour conflict management training program, the length of complaint calls about bills that were judged to be too high by customers was reduced by 22.3 seconds, saving the utility company $335,000 per year.9 Nonetheless, we can’t say for sure if other operant variables impacted the length of these calls. For instance, the measurements may have taken place when customers were distracted by other issues, or the overbilling may have been significantly less complicated during the period the measurements took place.

A United States client we worked with was able to effectively reduce the size of its escalation service staff because the representatives who first talked with the customers were able to turn situations around before they reached the point where customers wanted to discontinue service. We would like to take some credit for this reduction in costs, but one of the realities we have to accept is that many aspects of business are so complicated that precise proof may be difficult to obtain. Donald Kirkpatrick, training evaluation expert, says to be satisfied with evidence because proof is usually impossible to get.10

Challenge number three is that customers tend to score satisfaction survey scales high. Statisticians know that most distributions of measurements will produce a bell-shaped curve. In such distributions, the majority of items measured will fall around the midpoint, with the high and low ends being considerably smaller and not looking much different from each other. Here’s how a perfect bell-shaped distribution on a one-to-five scale might look:

126

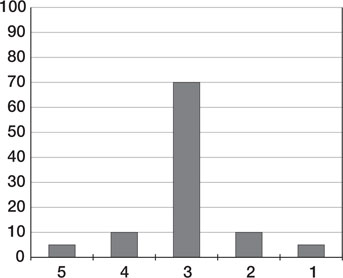

When customer satisfaction surveys are conducted by organizations themselves, however, it is common to find distributions that look like this:

When this happens over and over again, we have to ask ourselves, What exactly are we measuring? Academic researchers are seriously concerned about this skew. If I am a manager and being evaluated for my levels of customer service, I want scales with lots of high-end evaluations, but how useful is the information? What is a scale that looks like the above one really telling me, besides giving me bragging rights?11 Larry Keeley, president of a Chicago-based consulting firm, harshly judges these types of surveys as a way to find out about your customers: “These surveys are nothing more than tracking studies, designed to measure if customers are a little more or a little less pleased with you than they were last year.”12

Janelle took a vacation with her family to a famous resort. It was very nice, though there were some problems. A couple of months later she received a telephone call from J. D. Powers asking her to assess her stay. She gave the resort the highest rating on every dimension, even though she didn’t experience total satisfaction. All the while she was answering questions, Janelle was aware that she was contributing to this “skew.” Why? First, she genuinely likes this hotel chain, and she wanted to “reward” the company. Second, she was in a hurry; someone was waiting in her office to see her, and telling the interviewer to rate everything at the highest level saved considerable time. Finally, the questions were about a specific resort, and she didn’t want to get any of the staff there in trouble with their corporate offices. So she didn’t discuss any of the problems her family experienced.

Many organizations use feedback reports to gather compliments.

Many organizations use feedback reports to gather compliments. The results of many satisfaction scales are, in essence, public documents and extremely useful when companies want to advertise they have higher scores than their competitors. Unfortunately, if an organization uses its survey data this way, it becomes difficult to also use feedback scales as a means to improve. If this is the case, then you had better have another set of “books” that tell you what your customers 128really think of you. It is not a good idea to fool yourself about customer feedback.

In fact, the rosy picture that many companies have of customer satisfaction may lead them to an exaggerated sense of how their customers feel about them. James Morehouse, vice president for supply chain integration at A. T. Kearney, reports, “We have found from our research that most companies grossly overestimate the satisfaction levels they provide to their customers.”13 We wonder if airline personnel get taken in by the warm smiles of disembarking passengers who say “thank you” to the cabin crew and pilots. Realistically, how many passengers are going to stop at that moment and register complaints?

We have talked with representatives of a cruise line that consistently receives 97 to 99 percent satisfaction ratings on a 100 point scale. Those are exceptionally impressive numbers, but what is their message? High scores on that order probably mean that most customers circled the highest number, so the cruise line got a lot of 100s, which then pulled up the averages of those passengers who circled lower numbers.

Now don’t get us wrong. This is an exceptional cruise company; it offers a truly exciting, memorable—and expensive—product. If the next cruise, however, receives a 96 percent rating, how does this compare to a 97 or 98 percent rating? Is it possible that weather influenced the scores? The president of this cruise line, while obviously pleased, will also acknowledge his frustration with these scores. He sails on his ships with a yellow legal pad, and by the end of the cruise he has taken pages and pages of single-spaced notes listing items that didn’t meet his high quality standards. He says he doesn’t want to get lulled by high survey numbers. We like this attitude!

It is fairly easy to get customers to choose higher ratings by the way the questions are posed.

Satisfaction surveys in the health-care industry are particularly criticized for the way they superficially measure customer attitudes. Since these scales are published on the Internet, it is understandable that health-care corporations want the highest ratings possible. It is fairly easy to get customers to choose higher ratings, not only by the way the questions 129are posed but also by the choice of the scale itself. For example, if a company uses a four-point scale, instead of a five-point scale, respondents will more likely choose the higher rating off the midpoint, rather than the lower. The use of words to describe the categories can also skew results. If the choices customers have are poor, good, very good and excellent, they may be reluctant to choose poor because it seems in a different universe from good, very good, and excellent. Good is still in the lower half of the scale, but the company will be able to announce to the world that 85 percent of their customers rate their service as “good” or higher.14

Let’s go back to our “skewed” scale on page 126, where most of the customers rate the organization at the highest levels of satisfaction. Is it possible that useful information could be pulled from such a set of results to get a separate picture of just the highest raters?15 Of the highest raters, perhaps only 20 percent of these were truly “wowed” by the service they received. Maybe the rest were satisfied because they had no problems, but certainly nothing was added to their emotional accounts. They got problem-free service, perhaps somewhat better than the competitors’, but that was all. If this is the case, probably only 20 percent of the highest raters will likely form or deepen loyalty to the business or brand. If 30 percent of the total surveyed population rated service levels at “5,” that would mean that perhaps 5 or 6 percent of customers actually deepened their feelings of loyalty.16 This is a very different picture from that given by a first glance at such high satisfaction scores.

One might think that after all these years of studying customer satisfaction, we would know exactly what it means.

Challenge number four in capturing customer reactions to service is that we have no clear agreement as to the meaning of “satisfaction.” One might think that after all these years of studying customer satisfaction, we would know exactly what it means. Actually, there is little agreement about what it means operationally. The dictionary tells us that satisfaction “implies complete fulfillment of one’s wishes, needs, expectations, etc.”17 That’s not a bad definition, but we do not believe that “complete fulfillment” is what most people have 130in mind when taking a survey. We suspect most people see “satisfaction” as somehow the opposite of “dissatisfaction,” which commonly means “I wasn’t contented.” If I wasn’t not contented, then I must have been contented, hence “satisfied,” but not necessarily completely fulfilled. Complete fulfillment is actually quite a tall order.

To compound the problem, satisfaction scales have an assumption built into them that the very factors that produce satisfaction will cause dissatisfaction if they are not there. This isn’t always the case. Because of the high volume of miles Janelle flies, the flight attendants on her favorite carrier almost always discreetly approach her and ask her what she wants from the menu before anyone else gets to choose. This way, Janelle invariably gets her food selection. Ask Janelle about this, and she will tell you she thinks this is an excellent piece of customer service. But what if the airline didn’t have this practice? Would the absence of this benefit cause dissatisfaction in Janelle? No. At the same time, it is these kinds of extras that enhance loyalty, that make regular deposits in emotional accounts.

In an attempt to navigate around the problem of the vagueness of the satisfaction definition, many surveys use gradations of satisfaction, such as the following:

The definition of “extreme” in the dictionary includes phrases such as “at the end or outermost point… to an excessive degree… far from what is usual or conventional.” When one looks at a scale like the above, “extremely satisfied” is way beyond “fulfillment of wishes, needs, or expectations.” If it genuinely meant this to consumers, we suspect customers would be reluctant to circle “5” with the frequency they do.

Satisfaction to one person may have little to do with satisfaction to another.

Furthermore, satisfaction to one person may have little to do with satisfaction to another. One customer may walk into a place of business expecting little, get more than he or she expected, and give the company high marks on the satisfaction scale. Another customer may walk into this same establishment expecting a great deal more and give the company low marks on a satisfaction survey.131 It’s conceivable that both customers received the same level of service, but one thought it was great because he or she started out with lower expectations than the other customer.18

This raises yet another interesting question. What is the relationship between satisfaction and service quality? Experts in this area suggest “that consumer satisfaction exerts a stronger influence on purchase intentions than does service quality.”19 For this reason, a clearer picture of customer repurchase intentions will be obtained if both satisfaction and service quality are considered.20 (To read more about the elusive link between satisfaction and loyalty, see Appendix C.)

For example, research in health care suggests that customers’ judgments of satisfaction are not necessarily based on the quality of care they receive. Patients may like their doctors personally and never switch practitioners, even if a misdiagnosis is made. Satisfaction in health care is mainly a short-term judgment of the last office visit, which may not have a lot to do with the long-term quality of health care the patient receives. Bedside manner may be more important in creating emotionally happy patients and therefore loyalty, while “effective health care” may cause a patient to seek out another physician if it is delivered in a hostile, uncaring manner.21 This problem extends beyond health care and applies to most professionals—attorneys, accountants, financial advisers, architects, designers, psychologists, and consultants. If customers don’t understand how products could be better (computer neophytes, for example), they may judge themselves satisfied, while some other customers with more sophistication (computer specialists, for example) might be disappointed with the same product.