CHAPTER SIX

SATISFACTION ISN’T GOOD ENOUGH— ANYMORE

Setting goals to increase customer satisfaction is essentially meaningless.

It doesn’t take long before you realize that Michael Edwardson is saying something important, something different, something almost startling in the field of customer service. Yet as a listener, you find yourself accepting his thesis from the very beginning. Edwardson, a tall, articulate Australian on the faculty at the University of New South Wales, says point-blank that setting goals to increase customer satisfaction is essentially meaningless.

That, of course, is exactly what countless numbers of organizations do. This focus on customer satisfaction, according to Edwardson, “seriously limit[s]… our discovery and understanding of the total consumer experience.”1 In terms of creating loyalty, the most important aspect of customers’ experiences is emotional rather than satisfaction based. Harvard researchers Thomas Jones and Earl Sasser put it in operational terms: “ Customer satisfaction surveys cannot supply the breadth and depth of information about the customers needed 112to guide the company’s strategy and product innovation process.”2 This statement is pointedly relevant for the experience economy.

Edwardson reminds us that we don’t go skiing to get satisfied; we want to be thrilled, just as we do when we go to see the latest Hollywood blockbuster movie. If the only choice we are given is satisfaction or dissatisfaction, our judgment of the weekend of skiing might be high on the satisfaction questionnaire we were asked to fill in as we left the ski slopes, but our emotional state could be less than thrilled. And without the thrill factor, we might never go back to ski again at that resort, given the time, effort, and money it takes to spend a weekend on the slopes.

When we feel angry, using “dissatisfaction” to describe that emotion is completely inadequate. The last time Janelle’s luggage—containing all her work for a presentation she was to make in two hours to a critical client, and over which she had slaved for three full days—did not arrive at Chicago’s O’Hare airport, dissatisfaction would have been a pathetically weak description of the stinging rage she felt. After insisting Janelle check her suitcase, and all the while assuring her it would be in Chicago on her arrival, the agent sloppily tagged the luggage for a 6 P.M. departure, rather than the 6 A.M. flight Janelle actually took. And the O’Hare baggage assistant actually reprimanded Janelle in a scolding tone of voice, saying, “Now don’t get upset.” That might be good advice, but it was hardly an empathic comment at that moment.

There is disagreement as to whether satisfaction is an emotion.

Humans experience hundreds of emotions. Yet the service industry still relies mainly on one—satisfaction—to measure what customers feel. In fact, there is even disagreement as to whether satisfaction is an emotion. Some would argue that satisfaction is a judgment about emotions.

What if we used only one measurement of fitness, such as weight, for our indicator of physical health? It would tell us something, but as an overall measurement of health it would be inadequate and incomplete. In the same way, if organizations want to consider total customer experiences, satisfaction by itself is a weak measurement.

113While we do not have the final answer as to what is the best measurement of customer emotions, there are a number of interesting possibilities. In fact, there may be no single best measurement because the emotional connection between the service provider and customers is context dependent. Furthermore, this context is heavily laced with empathy, not one of the easiest emotional exchanges to quantify.

Emotional Accounts and Empathy

A vibrant and context-dependent metaphor of customer emotions that we think helps to explain a lot of customer behavior is that of emotional accounts. This idea, called “emotional bank accounts” by Steven Covey in his work on habits for families, paints an easily comprehensible picture of deposits and withdrawals. To a large degree, Covey’s emotional bank accounts metaphor refers to goodwill within our personal relationships. When the metaphor is applied to commercial relationships, its meaning is more demanding. Personal relationships come laden with social and family values that do not create the same constraints as in commerce. For example, a spouse who tolerates a roving partner may be considered a forgiving and courageous person willing to put the importance of maintaining the family above personal feelings. No one admires a customer who continues to go back to a supplier in the face of mistreatment.

Emotional accounts in commerce have to do with a reservoir of strong, positive feelings that are deposited and literally stored in customers’ memory banks. Each strong positive emotional experience (both material and personal) helps connect the customer to the organization until the customer reaches such a point of connectedness that it is a rare experience for that customer to purchase anyplace else.

As long as the total account is in the strong, positive range, there is a much better likelihood customers will stay where they are.

When there is a negative experience, a withdrawal is made against that reserve of positive emotions, and it must be repaid—with interest. Even neutral experiences probably make small withdrawals from long-term loyalty. At a minimum, they do nothing special, making it more likely that customers will at least be open to other suppliers. As long as 114the total account is in the strong, positive range, there is a much higher likelihood customers will stay where they are.

Emotional accounts is a useful metaphor for staff to use if they also see the purpose of business as “creating customers.” Every time they have a customer interaction they can ask themselves whether they added to or subtracted from a particular customer’s emotional account.

Strong, positive emotional feelings are most likely to be created when the customer–service provider interface is empathic—when, in other words, emotions are shared and mutually understood. Consider the following example from the trust and estate business. An in-depth survey revealed that 84 percent of trust beneficiaries felt their trust professional did not understand the pain they were going through while handling financial arrangements necessitated by the death of someone close to them. Of that 84 percent, 78 percent (or a total of 65 out of 100!) expressed a desire to switch financial institutions, primarily motivated, as they said, because of the lack of compassion offered by their trust officer.3

Many trust professionals think their accountability ends with meeting fiduciary responsibilities, the collection and disbursement of financial assets. Yet it is not uncommon for trust officers to spend time with clients or relatives of clients who tell them, “I no longer feel like living now that my husband has died.” Still, trust experts Janine Smith and Gaylon Greer write that in most trust and estate offices, no one “acknowledges [client] death[s] as anything other than a business event.”4

As a result, they publicly express little emotional response at the death of their own clients, even though many of them get quite close to clients in the process of setting up trusts and wills. The power of empathy teaches us that customers are not best served solely by accurate dollar calculations, but as Smith and Greer put it, “if trust industry employees are to participate in the full experience of providing service to 115customers they must be willing to share those customers’ fears, weaknesses and pain associated with illness and loss.”5

Empathy does not mean that service providers become embroiled in their customers’ emotions. Empathy implies sympathetic listening, without becoming consumed with the problem. As a result, staff must learn not only how to feel genuine sorrow for their customers’ plights but also how not to take those feelings of concern as burdens on themselves, perhaps carrying them home in the evening, where they prevent restful sleep and rejuvenating interaction with family and friends.

Empathy necessitates a careful balancing act for service providers. We want our medical personnel to care about us, and yet we do not want them to be disabled by their caring. We expect firefighters, police officers, and medical personnel, among others, to be able to put aside strong emotions and cope with the emergencies at hand. Computer technologists must be able to cope with the frustration of a customer whose system has just crashed and yet provide accurate technical information. And a doctor’s office staff must manage lengthy physician delays, balancing the difficulty this creates for patients who show up on time for their appointments while being responsive to the reality of medical emergencies.

After staff grief training, customers reported they feel safer and expect good things will happen.

One branch of Barnett Banks Trust Company, in Clearwater, Florida, has taught staff how to manage patient grief without assuming their clients’ emotional burdens. As a result of this special training, staff no longer view spending time with grieving customers as a threat but as an opportunity to share support and knowledge. When customers open trust accounts, staff now give as much priority to personally getting to know their clients as they give to understanding their clients’ financial situations. These behavior changes have impacted Barnett Banks’ customers, who now report that they not only feel safer with the bank but also believe they will benefit from their relationships with trust officers.

Barnett’s training program puts flesh on its vision statement, which reads in part: “Barnett people are caring and proud. We improve the lives of our customers and the well-being of our communities. We help each 116other succeed, and make our customers feel like they belong.”6 This vision statement is not all that different from many company statements we have seen. But Barnett, through its training programs, helps staff understand how empathy resides in those words and in so doing maximizes customer experiences.

Timothy Firnstahl, owner of Satisfaction Guaranteed Eateries, Inc., understands the power of empathy. When his restaurant staff call customers and ask them to rate their recent dining experiences, they give the customers the following choices: lousy, OK, good, very good, or excellent. Firnstahl says, “If they said ‘OK,’ that meant ‘lousy’ to us, and they got a letter of apology, a certificate for a free meal, and a follow-up phone call.”7 Firnstahl, in the process of surveying his customers, demonstrates empathy by assuming “OK” is an inadequate emotion for someone who has paid to dine out. Through their survey process, Firnstahl’s staff puts something back into customers’ emotional accounts after a withdrawal has been made by an “OK” dining experience.

Even though they don’t use the phrase “emotional accounts,” a growing group of marketing experts, including Michael Edwardson, is among the first to address this tricky but important issue.8 As previously discussed, this group is charting new ground by combining concepts from social psychology, consumer behavior, and the study of emotions to better understand and measure customer experiences that are inadequately described simply as satisfied or dissatisfied.

If all we do is look for satisfaction, we won’t focus on understanding the emotional meaning of the service experience to them.

If all we do is look for satisfaction, we won’t focus on understanding why customers feel drawn to return to organizations or the emotional meaning of the service experience to them. Furthermore, if staff rely on customers to report when they have experienced negative emotional reactions, service providers won’t be looking for subtle emotional communications that may not be expressed verbally. If service providers understand, however, that customers are building emotional accounts, then they will more likely try to enhance service experiences 117when situations are going well and turn around negative emotions when service experiences go awry.

Emotional Reactions and Satisfaction

We have an opportunity to bury the widespread notion that satisfaction is by itself an adequate measurement of customer retention—even if it feels right on the surface. A high-tech client has a customer who buys a lot of the company’s equipment and then calls repeatedly with one problem after another. He is persistent. After several years of this, the company told the customer that perhaps he should consider buying products from another company because obviously our client wasn’t able to satisfy him. The customer declined this offer. “You’re too good a company to produce poor products. I like your products, and I want you to get better,” he argued. “I’m going to continue buying what you make, and I’ll keep calling when something goes wrong,” he concluded.

Isn’t it interesting that a dissatisfied customer can be a strongly loyal customer?

Isn’t it interesting that a customer beset with problems and dissatisfied with product performance is, in this case, a strongly loyal customer? How do we explain such behavior in terms of the satisfaction/dissatisfaction scale? Obviously we can’t. But the emotional account metaphor goes a long way in explaining how someone can have one bad experience after another and still feel loyal. Somewhere along the line, this customer experienced enough positive emotional deposits that he wants to continue doing business.

Edwardson has measured the emotional reactions of people who fill in customer satisfaction surveys. He correlates ratings on 1-to-7 satisfaction scales with emotional reactions that he ascertains through in-depth interviews. His findings should be enough to make all managers focus even closer attention on the limitations of satisfaction surveys.

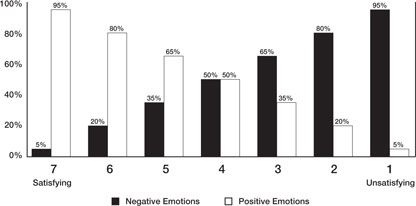

If customers’ statements of satisfaction were truly related to their emotional reactions, we might expect that customers who check “1” as their level of satisfaction (on a scale from 1 to 7) would have a lot of negative reactions to whatever happened. If they checked “7,” that would logically 118indicate mostly positive emotions. In fact, if satisfaction ratings and emotional reactions were exactly correlated, they would be related to each other as illustrated in the following graph, labeled “Logical Customers.”

Logical Customers

It is only at the highest levels of satisfaction that customers have more positive emotions than negative.

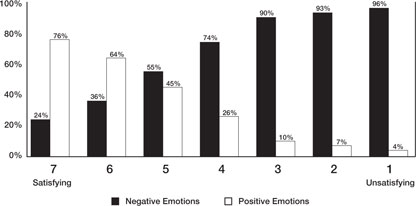

Based on his research, Edwardson has found that the emotional reactions of real customers, as they relate to satisfaction evaluations, look quite different from the “Logical Customers” graph.9 As illustrated in the graph below, at the low end of the rating scale (1, 2, and 3), negative emotions are consistently higher than expected. At the midpoint (4), negative emotions considerably outweigh positive emotional reactions. According to Edwardson’s research, customers who check the midpoint of satisfaction surveys still have almost three times (74 to 26 percent) as many negative reactions as positive emotional reactions. In fact, when someone checks “5” (in the upper half of the scale), the amount of negative emotions is still higher than the amount of positive emotions (55 to 45 percent). At “6,” the customer finally shows more positive emotions than negative. It is only at “7” that customers experience significantly more positive emotions than negative. Even at “7,” however, the negative emotions are still considerable (24 percent).119

Real Customers

Percentage of Positive and Negative Emotions for Different Levels of a Satisfaction Scale

Encounters - 325

Source: Michael Edwardson

University of New South Wales

Midline satisfaction survey ratings are not good indicators of intention to repurchase.

Many customer service managers we work with are extremely happy to receive “5” ratings from their customers on a 7-point satisfaction scale. It’s not enough. Based on Edwardson’s research, midline satisfaction survey ratings (4 and 5) suggest no intention to repurchase. There’s not even enough positive emotion stored in customers’ emotional accounts at “6” to create much loyalty because of the strength of negative emotions.

Professor Prashanth Nyer, at Chapman University’s School of Business and Economics, has demonstrated that the felt emotions of anger, sadness, and joy are the best predictors of consumers’ future behavior. Experiences of joy mean repurchasing is likely, while sadness and anger indicate repurchasing is unlikely. Dr. Nyer also found, as has Edwardson, that “emotional responses [are] distinct from the evaluations 120that subjects [make] about the product.”10 This research makes a lot of sense. A diner can have two meals, essentially identical from the standpoint of food quality, speed of seating, ambience, cleanliness, and price. Yet one dining experience could be pleasant and the other personally embarrassing or disappointing, depending on the behavior of restaurant staff.

Some organizations attempt to steer away from problems inherent in the satisfaction/dissatisfaction scales by choosing measurements they think are important and then asking their customers whether they delivered. Depending on the type of questions they ask, this approach can end up creating much the same situation as traditional types of satisfaction surveys. For example, we’ve seen hotel surveys that ask guests about the importance of items such as “service provider was polite” or “hotel room was clean” on one-to-five scales. Customers are then asked to judge how the hotel performed on each item. If you put any thought into it at all, you realize that of course hotel guests want politeness and cleanliness in their service experience.

Without a desire to return, customers are not long-term pieces of business on which organizations can count.

But such surveys don’t tell the story of what fills a customer’s emotional accounts. The check-in clerk may have been polite but didn’t make the customer feel welcome, didn’t recognize the customer even though this guest stays at the hotel several nights a year, and seemed to have a more intimate relationship with the computer than with the customer. Yes, customers may have been satisfied with the degree of politeness. They certainly would think its absence to be important. Customers might return to this hotel out of inertia, because the rates are good, or because of the hotel’s location. However, those customers may not feel an ounce of excitement about returning. Such customers are certainly not long-term, dedicated, loyal customers on which the hotel can count.