CHAPTER ten

Recording for Animated Features, Games, Theme Parks, Toys, and Narration

Other Areas of Animation

Up until now we have been discussing voice-over for animation more generally. Much of the work in animation is for animation television series. However, voice-over work is also available in animated features, games, toys (perhaps not animation, but closely related), theme parks, the Internet, and narration. These fields are often closely interrelated with characters going from one area to another. Actors who do voice work for animation may do voice work for any of these. This chapter covers many of the differences in these other areas. Practice copy is available at the end of the chapter.

Animated Features

Most animated features have bigger budgets than those for television. The voice-over work will probably be (SAG) union work in the United States and pay better than a session for television. As there is more time to cast and record the voice track, more care is taken with each line. More producers are apt to be involved. On a big budget feature there may be one editor just for dialogue, one for sound effects, and another for music. There may be a separate editor working on the picture plus a mixer. And all of these may be working at the same time. You may have a director, producers, and writers in the booth. You may have a local director from one country and a supervising director from the country that is producing the film.

Most films meant for the international market are recorded first in English, as english is still the language of international films. If the film is being animated in a country where the language is not English, then it may be dubbed into the local language early on for the animators there. Otherwise the film will probably be dubbed into other languages after the film is complete or nearly complete. Films made only for a local market may be recorded in the local language, although most Spanish films are recorded in English first by American actors living in Spain, just in case the film is very successful and the producers want to distribute the film outside the country later. Animated features in India will usually be recorded in Hindi for the domestic market; India has a unique problem in that the country has fourteen official languages and more than 1400 dialects.

Celebrities are usually cast in some of the principal roles in animated features produced in the United States. Tom Sito, who was animation director for the Warner Bros. film Osmosis Jones and many other animated projects, reminds us that celebrities are usually stars for a reason. They have a special something that they can add to a project. William Shatner can turn his emotions on a dime, which is part of the reason that he’s funny. Name recognition also helps draw in an audience. When the producers/directors were pitching Osmosis Jones, no one took them seriously until Will Smith was brought in on the project. Tom likes to have name actors in mind early rather than having auditions for the leads. Tom worked in New York and Canada before working in Los Angeles. He says that in New York and Canada, away from the stars and with smaller budget projects, the directors were unable to cast a big star and would look for someone like (insert name of star here). Raul Garcia, an independent director of animated films, feels that Robin Williams is responsible for the interest in using celebrities in animated films. Robin added a great deal to the Disney film Aladdin with his ability to improvise. Local celebrities may be used as well in dubbed films or animated films made for the local market in places such as Spain, Germany, and India. Name recognition helps, as the celebrities can make appearances on TV, publicizing the film. Because most local dubbing pools of actors are usually small, audiences may recognize the voices as those of other well-known characters. Local directors sometimes use this recognition in their gags.

Animated features are almost always recorded one actor at a time. It’s difficult to coordinate the schedules of the celebrity actors, and recording each actor separately has become standard. Tom Sito creates sides for his actors, numbering the lines. He takes out many of the stage directions, descriptions, and extra action. It’s been his experience that many actors prefer this. Sometimes he glues his scripts onto a shirt board so that there’s no paper rustling on the sound track. He likes to bring in the character designs. If he thinks it will help, he’ll also bring in the storyboard. He believes that a director should not tell his actors how to do their jobs. He likes to exchange ideas with his actors instead, and he will change something on the fly if he gets a better idea. He’s found that during the recording session, rephrasing dialogue and streamlining may be necessary.

Occasionally, a professional voice-over actor is brought in to record a scratch track for an animated film early on, so that the work can begin on character animation, but the scratch track is later replaced by a celebrity voice. Perhaps the star was unavailable when the track was needed. Perhaps the film is later reworked, and the celebrity is added at that time, as was the case when Harvey Weinstein added changes to Hoodwinked after the Weinstein Co. acquired the film. In cases like this the professional voice-over actor may have actually improvised some lines, during the original recording, to make it funnier. He was the one who gave life to the character, as the animation was done to the scratch track performance. Then the celebrity must come in later and loop his dialogue to the completed animation.

Raul Garcia is an American citizen who was born and worked in Spain. He explains the complicated process from an independent filmmaker’s point of view. Raul made The Missing Lynx, codirected by Manuel Sicilia, and they raised their own financing. The film was animated in Spain. They hired a group of American actors in Spain, who work as a package, and cast the film without celebrities. They made the final casting selections. Raul sent his actors a complete script prior to recording. He prefers this. (He tries to show his actors character designs and storyboards, if they’re done by then. His initial recording session may be a scratch track with only one to three actors doing all the parts.) He recorded his scratch track. He later recorded a Spanish (Castilian) version for distribution in Spanish-speaking countries. He recorded his English version celebrities after animation, wherever they happened to be at the time. Then the Spanish distributors decided that they needed some Spanish celebrities in the Spanish version, which was supposed to have been completed. He needed to go back and recast some of those voices, record, and edit them into the Spanish language version. During production of an animated feature, some gags and some dialogue are almost always reworked. So he does his final English language recording after animation has been completed, recording all his actors separately. Raul likes to replay what the other actors have already recorded in a scene, so that each actor can play off what the prior actor has already done. He tries to do about three different takes plus one take the way the actor sees it; this may be improvisation. So you see that the process can be complicated.

A major motion picture studio, such as Disney or DreamWorks, usually has the luxury of recording with the final cast before the film is animated because everything, including financing and staffing, is already in place. However, even major studios may have changes during production that will need to be recorded later.

Ruth Lambert, who has cast many Disney films, looks for good voice and speech training in her actors, and she feels that a background in improv is good as well. It’s also important to her to get actors who are easy to work with, as the feature process requires a long commitment of time. She starts casting early, and actor changes may be made up to six to nine months before the feature is released. She has always worked with resumes and headshots, and she still likes to have these in hand when she’s casting. Disney does not use scripts in the initial casting process as they are still a work in progress, so they mainly use sketches, synopses, and character descriptions. At Disney they redo a great deal. Directors there have a reputation for being perfectionists.

Tom Sito looks for actors who will take their job seriously and be professional. He expects them to read the script they have been given prior to the recording session. He looks for versatility in his actors. He looks for actors who can do impersonations and lots of different characters. He likes to hear a musical quality in their voices. Some of his best actors had radio training. They could quickly give him something three different ways. If Tom casts a celebrity, he wants to use the celebrity’s natural voice and not some cartoon voice. Tom doesn’t like to use actors who sound alike. He looks for chemistry between actors. He sometimes finds it interesting to hire two comics who will try to top each other as they work. He believes that some of the best lines come out of improvisation. He believes that audiences respond to that, to a kind of roughness that seems more real, perhaps because they’ve seen so much reality TV. He especially liked the spontaneity of a lot of the dialogue in Surfs Up. Tom records walla and sound effects at the end of each session. These are sounds that will be edited into the track later (“Ug!s,” pants, sighs, etc.). He prefers to create a library of sounds from his actors rather than bringing in a walla group later. He does this at the end of the session so that these sounds don’t tax the actor’s voices earlier in recording.

Director Raul Garcia believes that good acting skills are the most important thing an actor can bring. The actors that Raul works with are very versatile and are right on sync.

In the United States and London, Raul casts through talent agencies. The group he works with in Spain comes as a package, and they do their own casting. They are well known in Spain, as they do most of the English language work there.

Feature casting is often done outside the United States by local casting directors or local dubbing directors. They may be part of a package of director and actors. Usually for an American feature, an American director comes in for the recording session. He has probably had some input on casting, sometimes more, sometimes less. The local director will probably be directing the recording session, as he is more knowledgeable about his actors, and he speaks the local language. The two directors may not agree on everything, but the American director is probably in charge of the session overall. He may be directing the film or may have been hired by the motion picture company to supervise overseas recording and get what they want. It is hoped that the American director is sensitive to local cultural issues and ways of working. Most sincerely try to be. Some directors have said that the actors they’ve worked with abroad were better actors than the voice actors they worked with in the United States. Some have worried that the adaptations were less conversational than the English versions, whereas some have been concerned that in some countries getting the dubbing track to be in sync wasn’t taken as seriously as it is in the United States. The bottom line is that there are differences, and both directors and actors must work together to end up with the best finished project that they can.

Actors, who want to work in features in countries other than the United States, should look for groups of actors who work regularly in dubbing. Actors will probably get more work if they also speak English like a native, as well as their local language. Actors: Do you speak other languages and dialects as well? Are you a really good actor? Are you versatile? Are you good at dubbing? Can you work quickly? Does your country produce many animated features that are made for a local audience, or is most of the work in dubbing?

Games

Recording for games usually takes longer than features or TV, as there are more lines to record. “Final Fantasy” had 7000 lines. It took three months to record … every day. “Blue Dragon” also took three months to record. Because some games can continue to record for almost a year, a large commitment might be needed in time.

Scripts for games may look different. There may be no scenes. When you look at your copy, you’ll often see many one-sentence lines. “Look out!” “Here I come.” These lines may be used in a variety of situations during the game.

Each actor is normally recorded individually for original games (games that are being recorded in the original language). Usually, the recording sessions take place before the animation is done, but not always. Now there is software that can play the animation and then conform the dialogue to it, but many games are dubbed instead.

Play games yourself so that you’re familiar with the voices and how they’re used. As with cartoons, use the games to study what’s out there and the techniques used.

The voice work in games may be union, and most of the voice work in the Los Angeles area is now covered by SAG. That union has a special contract for games. It’s a media agreement that covers games and Web sites. The contract is different from the contracts for feature films and for television series.

Games may still provide some opportunities worldwide for new voice-over actors to get experience. The work for less experienced actors would not be union work and would pay less, and in the big animation markets more and more game work is now union work.

Games have come a long way since the early days. Actor/director Richard Epcar says, “Right now, to me, some of the greatest acting and writing is happening in games.” Richard believes that there are some incredible vignettes between the action that are a joy for actors, and that outside of the theatre, these sometimes heart-rending scenes are some of the most rewarding opportunities to be found for actors.

Although a few high-end games may use celebrity actors, sound-alike voices are also used sometimes on games. Many games have fights. If there is a lot of screaming on games, it can be hard on your voice.

A demo with a lot of funny voices may not help you get work in games, as most of the work is more dramatic. For games be sure that you have characters on your demo that are more action oriented and more realistic.

Casting directors look for variety when actors audition for games. Try to read each line differently (intense, calling out in the distance, quiet and in your face, with humor, etc.). Picture where you are and the circumstances of each line. Have a variety of grunts, groans, and other typical game noises in your repertoire.

MJ Lallo, who sometimes directs voice-over for games, in her studio at her editing console.

For preschool or educational games, directors usually suggest that you speak TO the player, picturing the child or adult as you do. In many of these games the listeners must listen, understand, and then act. Speak clearly. Use variety. Directors may prefer that you speak slightly slower for preschoolers, especially if you’re giving instructions. Some directors suggest that you give directions with a friendly voice, perhaps using some humor. You may be acting as the perky guide. Some directors suggest that voices for preschool games should be warm and encouraging, but the style really depends on the game and the role. Like all media, there are trends that change from time to time.

Dubbing Games

Original games are produced and recorded into the local language in many countries. The process is roughly the same. Adaptations are usually made by speakers of the foreign language in question (a native English speaker for an adaptation of Japanese into English). Japanese into English is often given to directors who specialize in dubbing and anime, such as Richard Epcar and Ellyn Stern in Hollywood, or it may be outsourced to cartoon casting directors, such as Michael Hack or Ginny McSwain. However, it is common to have the Japanese director or producer at the ADR session fully involved in the recording.

From English, games are most often translated into FIGS (French, Italian, German, and Spanish) in addition to Japanese. Games may be found in versions of Mandarin, Arabic, Korean, and Polish or other languages as well. Companies such as France’s La Marque Rose, England’s SideUK, and Germany’s Effective Media handle all aspects of translation, casting, and recording. Most of the European companies use experienced European ADR or dubbing actors. The actors may improvise some more colloquial versions of the original lines when they are rerecording from another language.

There are three main ways to record international dialogue:

1. Dubbing/ADR with the actors lip-syncing

2. Performing as written without being overly concerned about matching the mouth flaps

3. Performing with a possible variance of about 10% over or under the original timing

After a game is adapted and recorded, it is tested with native speakers playing the game to make sure that the adaptation works.

Toys

The same characters used in cartoons sometimes appear as toys. These are toys such as talking teddy bears and robots and interactive books such as the Leap Pad™.

Interactive books may use an audio cartridge, but the space is limited with perhaps only one or two megs. Sound files may be edited down to eight bit. Because resolution is low and clarity is an issue, actors must articulate well and put strong endings on their consonants. This is particularly important in books for preschoolers that teach phonics and spelling.

Normally, the toy company does the casting for toys. In the United States they contact talent agencies.

Theme Parks

The next time you go to a theme park, pay attention to the television screen as you wait in line. Often an animated character gives you directions and entertains you as you wait. Theme park copy tends to be more like narration. You will play a character, but you’ll most often be narrating as that character. See the section on narration later.

The Internet

The Internet is a growing opportunity for voice actors. Independent filmmakers and students often make an animated film, send it to film festivals around the world, and post it on the Internet. There are a few animated series running on the Internet, and there are humor sites that use cartoons. Voice-over artists voice animated greeting cards as well. Many of these opportunities are still in their infancy, but there is much promise here for the future.

Narration

Narration roles may be found in feature films or in theme park work. Even though these roles are narration, they are also character roles. These are not announcer jobs. It is some character who is narrating. It may be a character in the story or it may be someone you never see. This work is all about character and good acting. The acting may be more subtle.

Ask yourself the following questions. First of all who are you? Get in character. Who are you talking to? Another character? The audience? What are their ages? If it’s the audience, pick a special person in the audience. Visualize her. Talk directly to her. You’re telling a story. What’s your point of view? How do you feel about what you’re telling us? Are you giving us this information because you feel that it’s important for us to understand? Are you trying to impress us with your knowledge? Are you all seeing, all hearing, wise? Are you warning us? You may decide to make the narration “important,” like an old-fashioned radio news bulletin. Take an approach. Weave a spell. Now look at the copy. What are you saying? Where were you, and what were you doing just before the script begins? Make a choice. Break the copy down into beats or sections. There should be some change that makes each section different. Perhaps you’re describing the time period in the first beat, then you describe the castle, and then you focus on one of the characters. What makes you, as your character, change from one beat to another? What’s the thought process? What are you trying to do? How do you feel about that other character you’re discussing? Is she like one of your children, or do you dislike her intensely? We want to know who is good and who is evil from your voice. The script should flow as a whole, but we should hear changes from one beat to another so that there is variety and interest. We should learn something about you, the narrator, by your changing attitudes toward it all.

Other suggestions include keeping your energy up. We may want to see power, a person who commands. Resonate the words. Give it warmth. Use standard speech (unless you’re playing a character who does not speak that way). Say “uh,” not “A” (a girl, a clown). Elongate the vowels. Like the way you sound. Keep the words flowing and smooth. Refrain from using vocal highs or lows for no reason. Keep the volume consistent. Use your diaphragm and stay close to the microphone.

Practice Copy

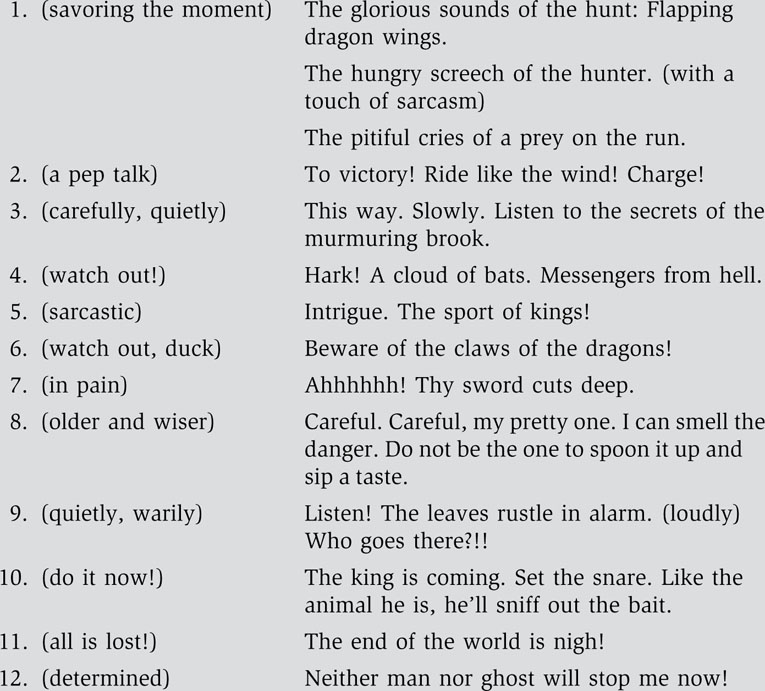

Dragon Wings (Game Copy)

Sir Henry: A knight, who’s been around awhile. Old enough to understand the realities of life, although he loves his country and feels strongly that it’s his calling in life to protect the people from their evil king.

Pip Goes to the Races (Preschool Game Copy)

Squeak: A yellow toy car. He’s called Squeak because of the way he suddenly brakes and squeaks to a stop. Full of energy and enthusiasm. He loves racing. His best friend is a red toy car named Pip.

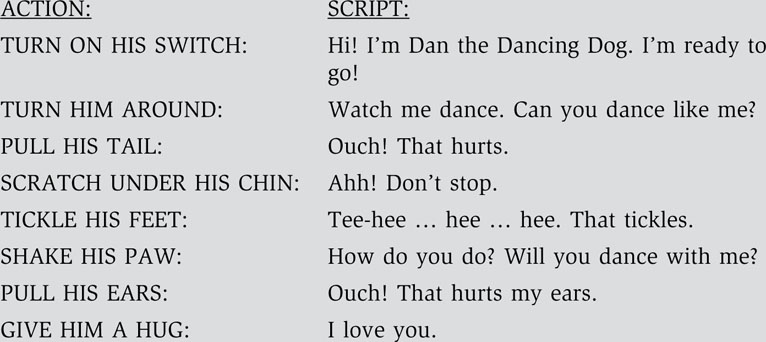

Dan the Dancing Dog (Toy Copy)

Dan the Dancing Dog: Dan can walk on two feet and dance around in a circle. He’s proud of his dancing ability. He acts like a three-year-old child. He loves everyone, especially young kids.

Garish the Gargoyle (Theme Park Narration)

Garish the Gargoyle: Garish is a fun-loving gargoyle on the roof of a theme park castle. He likes to gossip. He’s proud of the emeralds and rubies that decorate his neck.

| Garish | Garish the Gargoyle here! Look up. Over your head. Yes, that’s me fourth gargoyle from the end. Do you like my bling? Don’t you just love anything that’s shiny? It’s going to be a few minutes until the castle gates open again. The staff is busy tidying up after the last guests. Sir Henry’s pet dragon took a dislike to the sorceress’ cat, and they’re still putting out the fire. The wait won’t be long. Did you bring your brollies? No? Then just pray that it doesn’t rain before the gates open. They tell me that it’s not a good idea to stand under the gargoyles when it rains! |

Exercises

1. Take a script and cross out all the roles but the one you’re going to do. Leave in all the stage directions that affect you. Write in directions to yourself so that you know how you’re reacting to the others and why. Try reading the copy, reacting as if the other characters were there with you. Be sure to stay in character as you do. This is a good exercise to prepare yourself to record alone for feature animation.

2. Write some game copy for yourself. Practice each line. Try to give the lines immediacy and energy. Make us feel like we’re right there in the scene with your character. How should we, as the game player, feel? If the player is the main character, get inside his character and react to the action so that we the game player can react with you. If the player is there with you in the scene, think of him as another character. React as if he was there with you.

3. Borrow children’s books from the library to practice your narration. If the narrator in the book is not a character, then read that narration as if one of your own characters was the narrator. Record your reading. How can you make it better?

4. As a class, write a short script to post on an Internet Web site. Cast the script. Record it. Perhaps a storyboard class would do an animatic to go with it.