CHAPTER three

Animation Voice-Over Techniques

Chapter Techniques

In this chapter you’ll learn more voice-over techniques. The last chapter concentrated on the body and the voice. In this chapter we’ll cover many other things that you need to master. First we’ll discuss different types of microphones and the techniques for using them. What do you need to know about your headphones and your copy stand? We’ll discuss marking up your copy and slating your name at the start of recording. What about the acting itself? We’ll look at improv techniques and comedy. We’ll cover things like human sound effects, laugh, cries, and animal sounds. We’ll talk about pacing, style, and energy level. Finally we’ll list some tips for reading your copy and some more tips for running your own voice-over business.

The Microphone

The microphone converts the sound waves into electrical impulses that can be mixed, equalized, and recorded. Microphones come in two basic directional pickup patterns:

1. Omnidirectional (or nondirectional). Sound can be picked up from all sides equally. These are rugged and least expensive.

2. Directional. Sound is most sensitive from one direction (or two in the case of bidirectional).

a. Bidirectional (or figure eight). Sound is picked up from front and back. It’s dead at the sides.

b. Supercardioid (or hypercardioid or shotgun). These have a very limited range and suppress sounds from the sides and rear. However, these are sensitive to ambient noise, reverberation, and echo. This microphone is ultradirectional and can pick up sound from a great distance, but it can pick up only a very narrow corridor of sound.

c. Cardioid. Most cardioids are highly sensitive within a 120 degree radius facing the mic (a heart-shaped pickup pattern). These are the mics used most often for voice-over work. When several voice-over artists are recording at once, technical considerations require as much separation of each artist as possible to avoid pickup from adjacent mics.

This condenser microphone is an AKG C 414. It’s a Super Mic with the ability to switch between five different directional (polar) pickup patterns: omnidirectional, cardioid, wide cardioid, hypercardioid, and figure eight. It’s covered with a pop filter.

The condenser microphone is an AKG Perception 400 blue mic with an external pop screen. It can switch from cardioid to omnidirectional to figure eight.

ADK 51 series condenser microphone. This is a cardioid mic. It has an external pop screen, as well.

There are several different types of hand or stand microphones, with the dynamic and condenser being the most popular for voice-over.

1. Dynamic (moving coil). These are pretty rugged and provide good-quality sound. They’re not easily overloaded by loud noises. The mics are classed as nondirectional, but do tend to be directional at higher frequencies (with lowerquality sound to the sides). Dynamic mics are relatively inexpensive, but of course, the more expensive models give the best-quality sound.

2. Condenser or electrostatic (fixed plates). These produce the highest-quality sound. They’re ideal for musical pickup. They usually have a clean, crisp sound. Relatively large in size, they need a special power supply. Condenser mics can be overloaded by loud noises nearby and are very fragile. These directional mics are also expensive.

3. Electret condenser. Directional cardioid. Wide frequency range for voice or music. Quality is pretty good, but it can deteriorate with time. Background hiss increases. It can fail due to high humidity, moisture, heat, and dust.

4. Ribbon microphone. Bidirectional pickup. High-quality sound. Large overloads with close loud sound.

Most often the microphone is hung from a boom. The mic may include a pop filter or pop stopper (a pop screen) or wind sock or wind screen (hollowed-out foam) positioned between the mic and the artist’s mouth to soften popping sounds. Not everyone uses the same terms for these. Some studios have a D-Esser, which helps control sibilance, although too much D-Esser can affect the quality of the sound, making it sound muffled and lispy. An engineer will set the microphone at the proper distance. Usually that position is to the side or in front of the artist above the copy stand at about forehead level. A music stand is normally used for copy. As the artist, you should position the stand so that you won’t have to tilt your head down and away from a hanging mic. Tilting your head down or up can also affect the quality of your sound by constricting your throat.

Ask the engineer to adjust your mic to the correct distance for you, if he hasn’t already done that. Your mouth should be roughly three to fourteen inches from the microphone. A softer voice should be closer to the mic; a stronger voice needs more space. Many actors use a standard test of spreading and extending the fingers of one hand. The thumb should be close to your chin and the pinky finger close to the mic. You will probably be speaking across the mic, talking either over or under. It doesn’t matter whether you’re directly in front or slightly to one side, but you should not be speaking directly into the microphone. This is better for sound quality, causes less breath pops, and allows less breath moisture damage to the microphone. When you’re working, you should keep your head in roughly the same place so that the quality of your voice doesn’t change. The rest of your body can move around. Heads bobbing closer and farther away will make the sound fade in and out. Even a few inches make a difference, and the changes will drive the sound engineer up the wall. If you need a lower pitched, more intimate sound, you can get that by moving closer to the mic before you begin to record. Being closer to the mic also produces a bigger and fuller sound. Use less volume as you go closer. Or you might try a sound that is more breathy (standing slightly to the side of the mic). Standing farther away lets in more room noise. If you need to whisper, draw closer to the mic. If you’re going to yell, back off to about twice the distance of your starting position or turn about forty-five degrees. As a general rule, the closer you are to the mic, the more problems you’ll have with sibilance. Keep your hands away from your mouth. A spread hand by the side of your mouth can cause an echo sound.

The engineer will test for sound levels before recording begins. Do this by reading your copy at the level you intend to use. This gives you a chance for rehearsal. The engineer may ask you to move in or out an inch or so. If you are making popping sounds, he may ask you to move more to the side of the mic.

In a session do not touch the equipment for any reason, except for the copy stand. In a class situation you may be asked to adjust the mic for your own height. If so, tighten it only to the point where the next person can loosen it easily. That goes for the music stand as well. Threads on equipment can be stripped easily. The equipment is expensive. Let the engineer adjust anything that needs adjusting. Never tap a microphone or blow into it. Blowing can seriously damage a microphone. Tapping is just annoying to the engineer. Don’t cough, sneeze, clear your throat, or make any other loud sounds directly into the microphone. You never want to get a microphone wet, drop it, or bump it. Most microphones are extra sensitive to sound. When recording, be careful not to wear clothing that makes noise. The microphone will pick up rustles, squeaks, and pops. Problems can come from nylon, leather, other synthetics, and jewelry. Loose change or keys in your pockets can also cause trouble. When you physicalize your acting, you want to refrain from stamping, clapping, hitting objects (or people), or making any other noise. Remember, too, to watch out for plosives that pop into the microphone. If the sound engineer has a problem with any of your plosives (b, c, d, g, k. p, or t), lower your chin just a bit as you say the offending sound. Another technique to avoid popping is to place your index finger in front of your mouth (as if to say, “Shh!”) or you can use a pencil instead of your finger.

Holding a Microphone

It’s unlikely you’ll be asked to hold a microphone, but it could happen during an audition. It should be held vertically or at a slight angle toward your mouth. The mic should be about an inch below your lips and away from the chin. Check to make sure that you’re not breathing directly into the mic by feeling for your breath with a finger. Keep away from the cord, as cord noises can sometimes cover up a reading.

Headphones or Earphones

You’ll probably be asked to wear headphones (or cans, as they’re sometimes called) so that you can monitor your own performance and sound quality. Headphones also allow the director, engineer, and others in the booth to communicate with you. These listening devices will always be provided, but it’s okay to take your own if you prefer. If you buy your own headphones, be careful that they don’t emphasize low frequencies. You want to hear the sound that is being recorded, not something that’s altered. Some studios have monitor speakers so that headphones might not be necessary.

Headphones are sometimes helpful in keeping your voice consistent and in character. They allow you to hear the music if you’re singing. They allow you to hear dialogue and sound effects if you’re dubbing or doing ADR.

Be careful that you don’t focus on your own vocal technique so much that the quality of your acting goes down. You need to be in the moment so that we still feel your emotions and believe you.

Also, be aware of the danger of long-term hearing loss from loud sound piped directly into your ears. If you are working many hours, you may want to ask the engineer if he can turn down the sound a bit or wear an earphone on only one ear, with the other behind your ear.

Copy on the Music Stand

You never want to rustle your copy. A half-hour script is pretty long. If you have a mic and music stand to yourself, place the script on the left side of the stand and drag the page over to the right when you come close to the end of a page. That way the next page will be clearly visible when you need it. Be careful not to make a sound with the page. If you have to share a stand, you can slide the page down a bit to see the top of the next page and then drop the page quietly on the floor as you finish.

Marking Your Copy

Hopefully you’ll get your script a day ahead of recording so that you’ll have plenty of time to mark it up, although you may not get it until the recording session itself. There are about as many systems for marking your own copy as there are voice-over actors. You decide what markings are most important to you. Develop your own system so that it’s more meaningful to you, personally. Mel Blanc used a different color underline for each different character. Almost universal is a line drawn under words that should be emphasized. But maybe you want to draw a heavy line to emphasize a word by making it louder. Some people draw arrows above words and phrases indicating where the pitch is raised or lowered. Arrows above a word or syllable, stretching it outward, might indicate emphasis by lengthening, whereas arrows, meeting together, might indicate shortening. Dots or slashes can be used for pauses. Don’t be afraid to change the punctuation that’s there; punctuate for meaning, not grammar. Feel free to add noises such as snorts, laughs, and gurgles. Experiment with phrasing. If you find a word that’s difficult for you to pronounce, rewrite the word so that you’ll be able to read it easily (Kyoto = kee-oh-toh). You can use abbreviations, symbols, different colors of marker, or draw faces for emotions. You might write in every changing want or need in each scene or beat. You might want to mark in places where you want to take a breath. Plan on taking a breath at the end of each thought, but be sure that you’ve planned enough breaths to get you through without gulping for air. Do go easy on the markup, however. You don’t want your copy so completely covered that you have to concentrate on the markings rather than your character.

In marking your copy you’ll want to consider the following:

1. Phrasing

2. Emphasis

3. Volume

4. Pitch

5. Rhythm

6. Timing

7. Pacing

8. Duration of syllables and words

9. Pauses

10. Punctuation

11. Diction

12. Breaths

13. SFX

14. Emotions

15. Needs

Slating

When you’re ready to record, whether it be in a class or at an audition, you slate first. Slating generally means that you say your first and last name and the character and title of the project. If you’re recording more than one take, you may want to add the take number. In class your name and character are enough. Other times more information may be requested of you, such as the name of your agent or other contact information. You may slate in your natural voice or as your character. Most professionals suggest that you use your natural voice, as that gives the director a chance to hear what you really sound like. Remember that your voice, as you slate, is often the first chance that those in the booth have to hear you. It’s best to slate big and happy to make the best impression. Wait a couple of beats after you slate before you begin to read the copy.

Good Acting

The techniques you learn are for practice. You use good techniques over and over until they are second nature. Then when you’re auditioning and performing, you forget them and focus as your character on what is happening right then in the story.

When you first get a script, read it over and make choices. What happened just before the scene started? Who are you talking to? You should know almost as much about the people you’re talking to as you know about your own character in order to make them real to you. What do you want or need in each scene or beat? What are you trying to do? What is your goal? Does your character undergo a transformation during the course of the script? Find the emotional changes. Mark each changing want or need in your copy so that you won’t forget. How do you get what you want? How do you feel about what’s happening? How do you feel about the other characters? Try thinking each individual thought you make in trying to satisfy your needs. Emotions come into play. Mel Blanc felt that his job was to take emotions and interpret them differently through each character, translating them back in human terms. The thoughts you have will simmer underneath and give the performance subtext. People seldom say what they’re really thinking. The thoughts and emotions you have will change your performance. Feel what you say. Anime director Ellyn Stern advises actors to interject their persona into the performance almost like a spirit so that they can make the character breathe. Physically, feel and act on your responses. Use your face and your whole body. Stretching your arms high over your head or waving them around up there can give a big boost to your energy level as well. Try it when you’re recording and see the difference. Comedy most often requires exaggeration, but sometimes less is more. Allow those moving, quiet moments to come out as well. Above all, be sincere.

Really listen to what the other characters are saying. In your mind picture the person or character you’re talking to standing in front of you and talk directly to him. Visualize your surroundings. Focus on that moment in time in that imaginary world. How do you feel about what they’re saying? React and let those reactions influence your performance. What you hear might take you in a different direction from what you expected. Go with the flow.

June Foray suggests that actors think about their emotions, “When you’re angry, when you’re happy, is your voice elevated? Is it lower? … Human emotion is extremely important.” Watch how other people react emotionally so that you understand what emotion does to your voice. When you react emotionally, stop and pay attention to how you feel and how that emotion is naturally expressed. Focus and listen to the other characters in a scene. Really feel the emotion in the script. If you’re supposed to be angry in the copy, get angry. If listening and reacting genuinely don’t make you angry, then think of something else that does make you angry and let the anger bubble to the surface. As an actor, you should be able to bring forth an emotion you need at will and then control it enough so that you can use it, but not let it overwhelm you. Practice until you can do that. The most convincing and believable acting happens when you truly believe what you’re saying and really experience the emotions as your character would in real life.

One other technique that can be used to breathe life into a long monologue is to insert a running commentary between the sentences, giving your character something to react to. Your character in the script says, “I’ve got to get to the Princess before that evil sorcerer does!” And the imaginary running commentary says, “You stupid jerk! Your horse is about to drop and you were up jousting all night. How on earth do you think you can do that?” Your character says, I’ll take the high road. It’s a shortcut.” The running commentary says, “Shortcut! snortcut! the evil sorcerer is going to get there simply by waving a wand.” And your character says, “First I’ll warn the Princess by blowing on my bugle.” You get the idea. The running commentary gives you something to react to and helps give you alternate possibilities for meaning in the script. In using the running commentary technique, however, remember that you still need to keep up the normal pace.

During your audition or during recording, use the choices that you made earlier. If your director wants different choices, then you’ll need to be flexible enough, versatile enough, and professional enough to make new choices on the spot and follow those through instead.

In the end, acting is all about truth. If we can believe that you really are the character you inhabit, then we get into the story and forget all the rest.

No matter how beautiful the quality of the sound, it’s really the acting that counts the most. Continue taking acting classes. Act whenever and wherever you can. Experience does help. Go over your copy beforehand. Analyze your character and your script. What does your character look like? How does he move? How does he sound? Why? What happened prior to the start of the script? What do you want in each scene? Mark up your script to help you read it. Then really get inside the character and believe what you’re saying. Who are you talking to? Picture them. What do you want? Focus on each need. Think each thought. Finally, have fun with it!

Practice Improvisational Techniques with Other Actors

If you get a chance to take a course in improvisation, take it. It’s great for learning more about comedy and even better for developing characters. It will help expand your creativity and make you more spontaneous. If you want to experiment with some friends, try these rules for your improvisations:

1. Say the very first thing that springs into your head.

2. Always say “Yes” to your acting partner. That means you agree with everything he suggests and run with it, adding more details. You never say “No.” You never start an argument. For the same reason, you want to stay away from “But.”

3. It’s your job to make your partner look good at all times.

Improv is supposed to be fun, not only for the audience, but also for the participants. It teaches you to take risks and to carry them through. The idea is to develop a sense of play. Don’t take yourself seriously. Feel free to make fun of ideas; if you’re having fun, the chances are your audience will be having fun as well.

Improv techniques are based on characterization. The techniques should not be based on funny lines or gags. What makes improv funny is the uniqueness of the characters and their relationships with each other. What makes it funny is each character’s passionate pursuit of his own goal and the uniqueness of how he does that.

Saying the first thing that comes into your head makes any scene unique. You are unique, and what you say will be a reflection of you and your experiences. The scene should not center around “what you think is expected of you.” It should be unique to your experiences.

By always going with the flow, saying “Yes” to your partner, and building on what your partner contributes, you and your partner work together to keep the scene moving. If you said no, it would be a competition, and the scene would stop moving forward in one direction.

Making your partner look good validates him, as he validates you. It allows the creativity to flow out without being shut down. It’s the juxtaposition of “what does not have time to be carefully thought out” as it flows from your brain, placed up against “what does not have time to be carefully thought out” from your partner’s brain. That’s what’s funny. It’s instant choices made confidently. It’s silliness. It’s unique. And it allows both of you to have fun.

It doesn’t really matter what you say. It’s the randomness of what you say and the confidence with which you say it that is funny.

When your partner asks you questions, answer confidently with the first thing that comes to mind. It’s a motormouth automatic response. If you get stuck, look at your partner and react to what you see and hear, “Does that green shirt help you in greening the environment?” “Does saying ‘Yes’ a lot get you clients?” You are reacting to your partner’s behavior to continue to move the scene along. Listen to what he has to say and continue to react.

When you use improv to develop your characters, let yourself be open and responsive. Make use of all your senses. Look, listen, touch, and smell. Let yourself be vulnerable so that you can react emotionally to what you experience. React instinctively and spontaneously without planning ahead. Do take things personally. You don’t have to follow society’s rules.

Although improv is not usually used in animation voice-overs, it is used occasionally. Robin Williams improvised much of his dialogue in Disney’s Aladdin. Jerry Seinfeld and Chris Rock improvised one whole scene in DreamWorks’ Bee Movie. Jerry (a bee) interviews the Chris Rock mosquito … all improvised. And Nickelodeon has been experimenting with improv as well.

Playing Comedy

In the medium of animation, the gags are often visual. There may be little dialogue involved in the gag. However, some television animation is more like a television sitcom, where the dialogue is important in the humor.

Most comedy is based on surprise. You lead the audience down the garden path (the setup) and then zap them with a surprise that seems to come from nowhere. That’s the sudden surprise, the twist, the punch line. The more unexpected the surprise, generally, the bigger laugh you’ll get, so you can’t telegraph the punch line. Typically, gags are set up with the basic information misleading the audience.

There is a rhythm to the gag … typically, dum, dum, de-dum. Setup, setup, payoff. Watch cartoons and situation comedy on television. Pay particular attention to the rhythm. You need to be able to feel that rhythm as you act. You need to know how fast to go and where to take the slightest beat to wait for the audience to catch up.

Comedy may be based on exaggeration, overstating the obvious. It can be based on discomfort, where tension from embarrassment explodes into laughter (bathroom humor, gross humor). It can be based on impersonation or disguise, multiple references, parody, funny sounds, misplaced emphasis, rhymes, and alliteration. Much of this comedy depends on the actor to make it funny. The comedy must be based in reality or it won’t be funny. Your character must believe what he is saying and doing. Judge when you need to underplay for the best effect. Comedy characters are often struggling to do something right and failing at it every step of the way. This is what makes Homer Simpson funny.

Comedy in animated features and in prime-time television is often multilayered to appeal to different age groups. The children get the obvious references, and the adults get the layer of humor that’s hidden to the kids.

Many people use their natural sense of timing to get the most from a gag. If you don’t have that yet, watch the old silent films and early comedies (Charlie Chaplin, Laurel and Hardy, etc.). The physical comedy of the early films is closer to that of animation. Listen to the old radio comedies such as “Jack Benny.” But also watch television sitcoms. Don’t forget to include the physical comedy of the old I Love Lucy shows, as well as the comedies that are on today. Study how the characters interact. Listen to how a joke or gag is set up and delivered. Listen to the rhythm and the timing.

Risk

Be willing to take risks. Voice-over is the process of trying something new. Sometimes it works right away, sometimes it works after a lot of practice, and sometimes it won’t seem to work at all. Be willing to try new things as you practice. Be more cautious in volunteering to try new things before a director, but do try them if asked.

Using a Wrinkle

Wrinkles may be done with the mouth or they may be changes in phrasing. Wrinkles include things such as adding a lateral s, a trill, a stammer, a crack or break in the voice, a snort, or a distinctive laugh. For a lisp, try placing the top of the tongue on the left side of the mouth between your lips. Experiment with the exact placement of the tongue and the amount of air you use. Other wrinkles include talking out of the side of your mouth, jutting out your chin, dropping a consonant, clenching your teeth, a quiver in the voice, and using your teeth as gums (tongue comes out front between the teeth as you talk like a toothless old person). You can pull your cheeks as you talk for a droopy-cheeked sound. Experiment. Find your own wrinkles. Work with them until you can add them effortlessly to your speech. You must be able to do multiple characters, not necessarily multiple voices. (See more about wrinkles in chapter 5.)

Voice Placement

Practice placing your voice in different areas of your head and chest. Do exercises to raise and lower your voice. Actress/director Ellyn Stern recommends dropping into a Kubuki pose (knees bent) to lower your voice. Visualize where you want to place your voice before you try to change the placement. (There is more on voice placement in Chapter 5.)

Human Sound Effects

The following are some human sound effects that you should be able to do convincingly or in a funny way for different ages:

Fight noises, punching and receiving blows

Huh! (You punch)

Ooh! (You’re hit in the stomach)

Sneezes

Ah-choo (two parts)

Coughs

Sniffs

Nose blowing

Snores

Hiccups

Burps

Gasps (inhaled)

Gulps

Spitting

Retching

Moans and groans

Fainting

Whistling (amazement, hailing a cab, wolf-whistle, whistling a song)

Eating

Drinking

Do these sounds as a baby, as a ten year old, as a teen, as an adult, and as an old person. Try them in character as a hero or heroine, as an evil witch, etc. Experiment.

Laughs

There are many kinds of laughs. There’s a maniacal roar, a polite “tee hee,” or a cackle. Try these:

Tee hee

Haa haa

Ho ho

Hmm hmm hmm (closed lips)

Heh heh heh

Mwha haw haw

Whoo hoo hoo

A-huh (Goofy)

Aha ha ha (Phyllis Diller)

Snort

Witch’s cackle

Woody Woodpecker

You should have a wide range of laughs in your repertoire. Big laughs need plenty of air and should come from the diaphragm. You might want to let them spill out without much control. Sometimes a build is good: “a-ha-ha-ha.” Let your laughs range up and down the scale. Give them different sounds for variety. “Ha-ha-he-ho-ho-ho.” Build the laugh from small to large and then let the laugh die down. Laugh on words. Laugh between words. Laugh until you cry. Be careful not to scream into the mic. The sound of the laugh depends on the character himself and his mood. What is he laughing about? How does he feel about what he’s doing and the other characters that are with him?

Cries

Experiment with baby cries. There are little fussing cries and big howls. How old is the baby? What is he crying about? Is he just bored? Hungry? Hurt? Really angry because he’s been crying and crying, and nobody cares? A toddler may throw a tantrum.

Animal Sounds

Work on different barks and growls. Try them for small dogs and for big dogs. The bark of a big dog should come from your chest. Use your diaphragm. Remember not to bark loudly and directly into the mic. Use variety. Highs and lows are important. Barks may come in a pattern: “Ru. Ra. … ra. … raf.” Try “roof” and “rawf,” “rohf” and “ralf,” “reh” and “rer,” “ha” and “hawof,” or “ruf, rof, rawf, rolf, ralf.” The f will barely be heard in most cases. Experiment with other barking sounds. Give your bark a burst of energy. Barks have different meanings, and so different sounds. “Get out of here!” “Save the kids!” “Someone’s getting my food!” “It’s freezing out here. Puh-lease let me in (whimper, whimper).” “This is my turf!” A growl might have a cough quality, letting the uvula vibrate. Try an “er” sound far back in your throat. Make your uvula vibrate. Try a sloppy wet intake of air and saliva before the growl. Give your barks and growls texture. Actor Gary Gillett, who specializes in sound effects, reminds actors that animal sounds usually come in between the words, so you don’t want to separate them but make the sound (like a growl) an integral part of the sentence, almost as if it is a word. Listen to the following real animal sounds, try to duplicate them, and experiment with them:

Barks

Growls

Meows

Pig squeals and snorts

Cow moos

Horse whinnies

Snake hisses

Cricket sounds

Screeching hawks and dragons

A mourning dove and other bird calls

The buzz of a bee

Then there are mechanical sounds such as the ticking of a clock, the screeching brakes of a car, and so on. Can you make these sounds a part of your characterization? You never know when sound effects might be needed.

Pacing

In television animation, especially, pacing is extremely important. Whether it’s comedy or action adventure, animation travels along at a fast clip. There’s no time for long pauses. This is not a thinking man’s literature like a novel or play. The kids require a fast pace to keep up their interest. Animators require a fast pace for both action and gags. Actors, speed up the thinking processes of your characters. Listen to the pacing of a typical cartoon and be able to move the dialogue right along. Cartoons have an energy about them.

When a single actor is recording a feature, the director can help speed up the actor by directing a few lines at a time. However, when a group of actors is recording a television cartoon that’s not possible, one actor can drag down the pace for everyone.

Style

Cartoons go through different styles at different times. Sometimes the work is for more natural voices, moms and dads, kids at school, or more everyday situations that are relatable to all kids. At other times animation tends to become more cartoony and imaginative with wizards, aliens, talking animals, and monsters from nightmares. Different kinds of cartoons require different kinds of characters—some more realistic and others more broad.

During the more natural cycles there may be a need for actors who have a more definite personal style that comes out no matter what character is played. During the cycles when character is king, then a more noticeable style may get in the way. Does a personal style come naturally to you? Get advice from teachers and mentors about how important it is to develop a style of your own. In either case it’s the quality of the characters you do and your overall versatility that are important.

Some agents and casting directors suggest that voice-over talent focus especially on one type of voice at which they excel. Are you especially good at being a bully? Then see to it that when a casting director must cast a bully, he thinks of you!

Energy Level

In addition to good acting, animation voice-over actors need to keep a high energy level. When you physicalize your performance, the physical movement helps keep that energy high. That means using your face muscles, your hands, and your whole body to express what you’re saying. Feel the energy flowing through. Let it burst out through your voice. Breathe life into those words! Let those emotions spill out so that we can hear how you feel. Keep that energy level right up through the very last line.

Tips for Reading Copy

1. While you’re recording, never take your eyes off the copy. It’s too easy to lose your place.

2. Never judge yourself while you’re acting. If it’s a practice session, listen to the recording and make judgments later. You can’t give a good performance if your attention is not focused on the thought processes of the character you’ve become.

3. Be sure that your words are clear and easily understood. No one can laugh at a joke that they didn’t hear.

4. Unless this is a very realistic project, you probably want to exaggerate. Don’t be subtle.

5. Keep your energy level all the way through to the end. Use a sense of immediacy.

6. Try holding your arms up over your head if you need to get more energy into your performance.

7. Keep your sentences from dropping down in energy and pitch at the end of each one. Sentences do tend to drop down in pitch, but you need some variety.

8. Use intensity, not volume.

9. Move along, and keep the dialogue flowing. It needs a rhythm. No clutter. No choppiness. But don’t rush.

10. Be consistent.

11. Use variety. Range up and down. Vary your pace.

12. Paint a picture with your voice. Put colors into it.

13. Underline adjectives with your eyes … and your voice.

14. A smile gives warmth to your voice.

15. Don’t be afraid to change the punctuation if you feel you have a better read. Feel free to add um’s, oh’s, giggles, snorts, and other sounds to make it more natural.

16. To give the effect of a character who has been running, take three breaths before reading the copy.

17. Don’t overlap the voice of another actor, as the sound will be edited. If overlaps are needed, the editor will do the overlap.

Tips for Running Your Voice-Over Business

1. Be sure that your attitude is friendly and pleasant at all times or you may not be hired again. Always be positive. The industry is small, and reputations for whining or bad behavior spread quickly.

2. Don’t dwell on mistakes. Move on. There will be bad times. Get through them. The good times will return. Keep your confidence during the bad times, and present yourself as a successful professional, always. Being an actor is much like being a salesman. But also remember to be humble during the good times. What’s that old saying about meeting the same people on the way down that you met on your way up?

3. Keep a small calendar or appointment book that you carry with you at all times. When you get a call for an audition or job, immediately write down the date, time, and location in the book. Keep track of your expenses in that book as well. You’ll need to jot down mileage, gas, parking, and so on for the tax man. Keep your receipts as well and file them by date in chronological order. Write on the back the business purpose of each.

4. Carry a cell phone or pager always. You must have a dependable voicemail number. Don’t change it. Check for messages frequently, and return business calls right away. Leave the room, if possible, to conduct your phone business. Keep the phone or pager turned completely off during a session.

5. Get a fax machine so that you can receive copy at home by fax, if necessary.

6. Keep good business records. Hire an experienced tax accountant. Check to see if you need a business license.

7. Keep a log of all animation classes, panel discussions, and other businessrelated activities. List everyone you meet professionally at these events. Keep cards or other contact information. What did you hear or learn? List any details that might help you in your business later. Try to make these notes immediately after each event so that you can remember everything easily. Many actors keep birthday lists and other important information about their agents, casting directors, and others they work with frequently to show a genuine interest in them.

8. Write thank you notes to helpful agents, casting people, directors, etc.

9. If your first language was not English, this may be a plus. Speaking another language like a native can get you work. Be sure to list fluent language skills on your resume.

10. Also, develop special skills such as imitating dogs or cats, babies, and sound effects.

11. Continue to take classes, go to panel discussions, and practice, practice, practice. Participate in local comedy improv classes and work when you can at local comedy clubs. Take part in local theatre. Network by joining local animation organizations and going to animation events.

12. Don’t let your agent price you out of the market. Continue to work for scale when you don’t have the opportunity to work for more.

Exercises

1. Play a DVD that you know well. Turn off the sound. Try improvising all the voices, duplicating the originals as well as you can.

2. Now play the DVD again, still improvising, but using your own original voices rather than the voices that were used on the DVD. Record what you do.

3. Read copy with a different twist each time:

4. Work with a microphone and copy stand, and experiment. Record the experiment, if you can, and listen to the results afterward. Change the placement of the mic. Read from the stand, experimenting with the height of the stand and the placement of the copy. Listen for the effect of your plosives. Raise and lower your voice without making much change to the sound level. Physicalize while keeping a consistent sound level, etc.

5. Find another actor to practice improvisational techniques. Use these techniques to make you more creative and spontaneous and to help you develop characters.

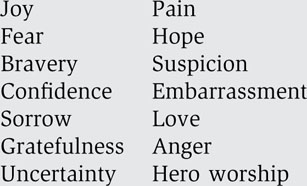

6. Work on expressing your emotions. Several emotions are listed below. Pick one at a time. Sit somewhere quiet, and plant the seed of your first emotion deep down in your heart. You can dwell on the emotion itself or think of an occasion in the past where you deeply felt the emotion so that you can re-create it. Let that emotion gradually spread into every cell of your body. When it fills you up completely and you can’t contain it any longer, let it spill out first into physical movement that grows in expressiveness and activity and then overflows into sounds and speech as well. Stop when you feel that you have peaked and fully expressed the emotion (but before you have harmed yourself, others, or the room around you). The goal is to really feel the emotion inside so that you can re-create that feeling whenever you need it.

7. Find some copy and record it, using a character voice. Wait three days and then evaluate your performance.