Chapter seven

The roles of the coach

•••

In extending one’s vision, the role of the coach evolves. This chapter examines a spectrum of the contrasting roles we adopt when we coach in moving from the analytical to the appreciative and creative eyes, including clarifier, conductor and co-creator. The evolution of this role is limited only by the imagination of the masterful coach.

•••

The role of the coach is not fixed, but changes quite dramatically, depending on the viewpoint we take.

As the coach learns how to expand their vision, their role evolves

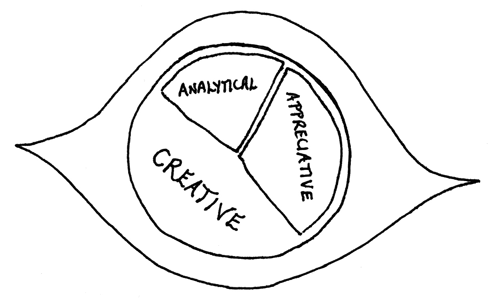

If we confine our vision or believe our role is fixed, then we can devalue the scope and possibility of coaching. When we discover the masterful coach we also find the exceptional vision of the creative eye. Let’s remind ourselves of the composite nature of this eye (see Figure 16, below) and how it informs the different roles that the masterful coach plays in practice.

Figure 16

• The analytical aspect of the creative eye •

I recently worked with a group of qualified counsellors and coaches who wished to explore and develop their coaching practice. I presented to the group concept of the three eyes of the coach and how these eyes combine to offer masterful practice. We discussed how they saw the role of the coach from the perspective of the analytical eye, and this was the list of possible roles that the group identified: trainer, instructor, problem-solver, controller, fixer, differentiator and clarifier.

Pause point

Which of these roles do you personally identify with and employ when you coach? How do they specifically serve your practice?

From the analytical perspective, the coach is seen to be a rational expert who imparts knowledge and information through instruction. We have already discussed how the analytical eye, when employed alone, can limit our potential to coach. This is because of the tendency of the instructor, for example, to want to fix rather than allowing the client the vital opportunity to find their own answers.

When the analytical aspect is combined and employed within the creative eye, it is much less reactive and more responsive. Here it provides a vital role to the work of the coach. Having helped the client to expand their awareness, the role of the clarifier is essential to the work of the coach. In every case study I have shared, you will note how, having employed the mirror to expand awareness, the lens of the creative eye is then vital to bring clarity and focus. Let me give you an example of the importance of the role of clarifier from a recent coaching conversation.

Philip is a senior physician within a major organisation. As he is being challenged by the complex matrix nature of his international role and the apparent lack of clarity around accountability, he sought help from a coach.

Philip: | In the matrix I’m not clear about who is accountable for what. |

Coach: | What is the result? |

I am using the mirror to expand awareness.

Confusion (pause). Things don’t get done. | |

Coach: | Anything more? |

Philip: | Fear, there’s a lot of fear. |

Coach: | Anything more? |

Philip: | Mmm (pause). A lot of protecting your own back, rather than getting the work done. |

Coach: | How does this affect you personally? |

Philip: | I’m frustrated and sometimes disappointed in myself. |

Coach: | How come? |

Philip: | I’ve begun to the play the game – to protect my back and not take accountability. |

Coach: | How does that affect you? |

Philip: | My motivation is dwindling. |

Coach: | You seem a little down. |

Philip: | I’ve taken the easy way out at times and it’s crossing me – my true values. |

Coach: | What values are being crossed? |

Philip: | My integrity, fairness and the importance of taking personal accountability for things. |

Having expanded awareness using the mirror, I now employ the analytical aspect of my vision – the lens – to help to clarify and determine the next steps.

Coach: | What are you learning from today? |

Philip: | I think it’s important to have heard myself say what I have said. |

Coach: | Yes, you’ve been very honest with yourself and courageous to speak so openly. |

Philip: | Something has to change. |

Coach: | Ideally, what might that be? |

I’m going to discuss the real issue – accountability and fear – with some of my colleagues to see if we can put on the table how we might move this forward together. | |

Coach: | How and when might you do this? |

Philip: | I’m meeting some of my key colleagues this week. I think I’ll do it after the conference at the bar maybe. I need a comfortable, relaxed setting. I’ll speak to two or three people and get a measure of whether they are struggling with the same issues as I am. I think they must be. |

Coach: | What do you need to help you to make this happen? |

Philip: | (Pause) Nothing. I’ve realised today that I need to do something for myself. I’m ready to move this forward. I have to for myself. |

Coach: | What would your ultimate outcome be? |

Philip: | Erm (pause). A meeting where we put all our issues on the table, name our fears and put things in place that free us to do our jobs much better. |

Coach: | Are you committed to do this? |

Philip: | Yes – I’ve got my motivation back. |

In this example you can see the importance of the role of the clarifier. The key aspects having been brought into awareness are then refined and distilled. The outcomes and next steps are brought into clearer focus, grounded and crystallised. Note how, alone, the analytical eye can profoundly limit the work of the coach, whereas in combination it provides an essential aspect of all coaching practice. In my own experience the role of clarifier is essential to ground the new awareness of the client and determine the next key steps.

• The appreciative aspect of the creative eye •

Recall the nature of the appreciative eye, the work of the inner observer and the value of the mirror. Let me share with you how, having discussed the nature of the appreciative eye, the same group described the roles of the coach from this perspective as: enabler, awakener, wayfarer, catalyst, conductor, facilitator, integrator, harmoniser, energiser, carer and supporter.

Pause point

Which role or roles do you personally employ when you coach and how do these serve you?

From the list there are three roles that are prominent in my own mind when I coach with the perspective of the appreciative eye. These are the wayfarer, conductor and carer. Let me illustrate their particular value to my own practice.

The wayfarer

The wayfarer is an important aspect of my conscience, helping me to remember why I coach. The wayfarer in me is willing to enter into the journey and adventure of coaching. One of my favourite wayfarers is Jason, of Jason and the Argonauts fame. Like Jason, when I coach I employ an enterprising eye and a willingness to enter courageously into the unknown as an adventure. Coaching takes courage and resilience.

To boldly go

I often view the beginning of a new coaching relationship as an adventure. I remember the journey of the starship Enterprise. Its mission, you are likely to remember, is ‘to boldly go where no man has gone before’. This starship ventures into the undiscovered expanse of outer space. The coach faces a similar adventure and challenge – not into outer space but more into inner space. When I think of the wayfarer, I am reminded that an important part of the journey of the coach is to be willing to explore the interior world of subjective experience, a world that the rational and concrete mind labels and fears as ‘the unknown’.

The adventure of not knowing

The coach as a wayfarer is willing to enter into the unknown to help to guide their own and their client’s learning and growth. Commonly when I coach I find myself in a place of not knowing: not knowing what’s happening in the coaching relationship, not knowing what my client is truly wanting or needing, not knowing where to go next. It is important that we realise that the experience of not knowing is a vital aspect of the coaching process and does not reflect ineptitude in any way, quite the opposite.

It is in these moments I remember the coach is indeed a wayfarer.

I can choose not to know as a means of fostering the growth of my clients

When I do this, I am able to give my full attention to the needs of the client rather than become anxious or fear that I am lost. The coach needs to be willing and able to stand beside the clients at their most challenging times – at the crossroads – and to enter willingly into uncertainty with endless curiosity.

When I coach, I coach myself to remember the value of not knowing the answer, for here is the chance to relate more deeply with my clients and to help them to discover their own answers. If, when we coach, we can step into the place of not knowing then, in that moment, we create the possibility for our clients to remember their deeper desire, and motivation, to change. Maybe this is one of the most important gifts we can offer – to be willing to stay and walk beside our clients, not knowing the answer, but caring enough to stay present and attentive to their needs rather than our own. This capacity and quality of relationship is an essential part of the process of how we learn and develop. Once more, I am reminded of this when I think of the role of the wayfarer and my work as a coach.

Meeting the monsters

Might a key part of the coaching journey be a willingness to face and meet with our fears? We may often make monsters of ourselves. Let me explain.

We often judge and reject parts of ourselves when trying to meet other people’s expectations. Some parts are labelled as bad and are banished to the edge of our awareness and beyond. In fearing these aspects of ourselves we make monsters of them. As we disown them, they appear alien and larger than life. The only option we seem to have is to fight them. I often recall how Jason always seemed to be fighting some larger-than-life monster on his journey.

But rather than fight, the coach is willing to meet with such monsters, to see them as rejected, lost and unwanted aspects of ourselves. If you are able to do this, then experiences find their true proportion. If allowed their rightful place, and we can meet with and accept them, then our apparent monsters no longer distort our self-perception or skew reality. This determination to face our fears and own our monsters is central to the work of the coach: in this way, we permit our clients the same prospect and possibility.

The conductor

When I coach it is valuable to remember the role of the conductor. The eye of the conductor tries to see and know all the parts of the orchestra. Although there can be solo instruments in an orchestra, the goal of the conductor is to harmonise. Generally, under the watchful eye of the conductor, there are no dominating divas. Through the work of the conductor the coach can begin to conceive of the orchestrated whole of which we are a part.

When I coach from the role of conductor, I remember my ability to stand apart and orchestrate. I have a clearer view of the different characters and instruments that comprise the orchestra (myself and my clients) and I can help to harmonise. The eye of the conductor is an integrative eye; it recognises and acknowledges the valuable contribution of each part and its relationship within the whole. Let me share an example of how the conductor can play a key role in coaching practice.

While I was demonstrating the possibilities of coaching to a group of new coaches, a client, David, presented a dilemma. David had checked into the group that morning having said that something quite wonderful had happened. He had returned from holiday where he had met some old friends. He had found himself working as a coach with two of these friends on separate occasions. Individually both had acknowledged how important and valuable conversations with David had been. Here is an excerpt from our coaching conversation:

David: | There are two parts to me. |

Coach: | Tell me more. |

One is a part that really needs to work hard.The other is a part that just wants to step back and take time out. | |

Coach: | How does that make you feel? |

David: | Caught, stuck. I have to work hard because that is what one has to do for a living. If I step back I feel guilty. |

Coach: | Recall what you checked in with this morning. |

David: | Mm (pause). Yes. |

Coach: | What I took from that, was that it seems that your real work is happening when you are on vacation, when you are relaxed and stepping back. |

David: | (Laughs) That’s true, I suppose. But that’s not hard work. I need to work hard. |

My conductor steps in to orchestrate the proceedings from here. David’s eyes see a further possibility other than the ‘either, or’ that is being played out.

Coach: | Maybe you can have it all? |

David: | How? |

Coach: | How can you meet the needs of both, rather than thinking you need to go ‘either, or’? |

David: | Mmm (pause). |

Coach: | Can you allow your good work to continue when you step back and also find a way of satisfying that part of you that needs to work hard? |

David: | Maybe (pause). Maybe I can – strange, I’d never thought of that possibility |

Coach: | Maybe you can have it all? |

When the conductor steps into the frame, I realise the value in orchestration. In this case there is a duet, rather than the dilemma of choosing between two soloists.

The carer

When I take the role of carer as a coach, I adopt a more relational and empathic position. This often makes me wonder if the appreciative eye is common to the caring professions. Is the role of carer employed in the professions of counselling, mentoring, psychotherapy and nursing practice, to mention but a few?

I have often heard it said that the higher one climbs the ladder of business success, the lonelier the experience. The capacity to care forms an essential part of coaching; it is fashioned through self-acceptance and demonstrated in how we encourage, support and guide others.

The carer reminds me of the importance of remembering ‘how we are’ in ‘what we do’

Caring and the capacity to empathise bring a vital quality to the coaching relationship. Such qualities often need no words to be deeply felt and can profoundly influence how we coach.

I feel privileged when a client is able to share and include their emotions in the coaching relationship. From my own experience, and from speaking with other coaches, the fear of feelings is often a fear of being overwhelmed by them and being unable to contain them. Remember, if we deny our emotions they can easily take super-human dimensions. We can unwittingly make monsters of what has normal human proportion.

We have explored how, with the opening of the creative eye, the coach can learn how to simply witness, meet with and experience emotions. A strong, stable inner reference and guide fosters self-acceptance and deepens our awareness of our own psychology.

The following excerpt demonstrates the role of the coach as carer – accepting, managing and containing the emotions of the client.

Mandy is a manager and leader. In our first session, having set the coaching frame, Mandy checks in:

Client: |

I’m Mandy and I’m a manager and I have a number of staff and I find it challenging work as there is always something going on that I seem to miss and it’s important for me to have coaching right now and I want to explore quite a few things but I’m not sure where to begin and I’ve got some things going on in the group and … |

There were no full stops, no breathing spaces and I was feeling as though I couldn’t breathe. I checked in with myself and decided to playfully intervene and mirror my experience.

Coach: | Mandy, dear Mandy, I am feeling exhausted and I’ve only been with you a few minutes. Are you allowed to take a breath or use a full stop (smile)? Phew! (Mandy looks at me and smiles shyly.) When did you last take a break (smile)? |

Mandy: | Is it that bad? |

Coach: | It’s not bad at all. I just can’t keep up when you speak fast and without punctuation. I feel lost and a little exhausted (pause). Is this a good place for us to work? |

Yes, I think so. |

I still can’t get my breath back and so decide the following step.

Coach: | Mandy, would you be willing to stop with me for a moment, so that we can just breathe together? Is that OK? |

Mandy: | Yes. |

Mandy stops and we just take a few deep breaths together. As Mandy takes several deep breaths in and out she bursts into tears. My heart opens as I see what may be sitting beneath her activity.

Coach: | It’s OK Mandy, I am with you. |

We continue just to breathe together – while smiling and reassuring her that it’s fine just to be here.

Coach: | So, Mandy, share a little more if you’re willing about what’s going on for you. Help me to understand. |

Mandy: | I’m not sure. When I get here I feel so lost. I’m tired and exhausted. |

Note how this mirrors my own experience.

Coach: | I’m not surprised. I wonder when the last time was that you truly stopped and breathed. You may not have been here for a while, so it’s not surprising that you may at first feel lost. |

Mandy: | Mmm. It’s true (pause). |

Coach: | Just take what time you might need. |

Mandy: | Yes. |

Coach: | Are you OK to work here? Is this the right place for you? |

Reminding Mandy about her choice is important – it places the power to decide back in her hands.

Mandy: | Yes, I know this is important. But I don’t understand what’s going on when I get here and whenever I stop talking I become emotional and often cry. |

Coach: | Is that so? |

Mandy’s feelings are overwhelming her. It may have been a while since she was last in touch.

Mandy: | Yes. |

Coach: | Might there be something important here for you? |

Mandy: | Yes. I might remember something I’ve forgotten. |

Coach: | Maybe. |

Mandy: | I know this is important for me to work here – this does affect me so much in my work and home. Is there another way I can work with this to understand what’s happening a little more? |

I hear the request for help. I return to my inner compass and guide and reflect and realise that I am very much still aware of the lack of breath. I decide that this may be useful and a positive context to work with Mandy. I don’t want to take Mandy away from her feelings and emotions, but I also don’t want her to feel so overwhelmed at being here. Is there a way she may make more sense of this experience? So I decide to plant a seed.

Mandy seems to have forgotten her own inner compass and looks to others for direction.

Coach: | That’s an interesting realisation, isn’t it Mandy? If you’re forgetting to breathe, try to remember what inspires you. Be curious, explore and consider what you desire to do. Begin to set your own direction. Will you try this and practise? |

Mandy: | Yes I will. I think this is spot on. |

Coach: | This is our first session but might this be an interesting theme for our work, I wonder? |

Yes, definitely. | |

Coach: | Are you OK if I remind you of your speed and breathing when we work together so that we can pace things? |

Mandy: | Yes, that would be helpful. |

This turned out to be a very interesting theme to our work. This context provided a meaningful way in which Mandy could be in what seemed like a difficult place. Even after one session Mandy began more consciously to manage the pace of how she was speaking and her breathing. She explored what it was like to add pauses and punctuation to her working life and began to remember and realise what inspires. Gradually she moved from running away from her subjective experience – her feelings and inspiration – to being able to trust and rely on these for guidance and direction. This personal change impacted both her work and her personal life.

If, when we coach, we are unable to meet with our own feelings, then we do not permit our clients the chance to explore this possibility for themselves

Note the importance of being able to provide a context, when working with emotions, that gives the clients’ emotions value and place – particularly with difficult emotions. When I coach I like to remind myself of the importance of the role of the carer and the associated integrative and appreciative eye that is willing to include and accept all feelings – my own and those of my clients.

• The role of the coach as seen from the creative eye •

The group collectively identified the following descriptions of the role of the coach as seen from this viewpoint of the creative eye: guide, gardener, reframer, transformer, resolver, a mix of artist and scientist, negotiator, mediator, synthesiser and co-creator.

Pause point

Which role or roles do you personally employ when you coach and how does this serve you?

Let me share with you how I mindfully employ the work of the roles of the gardener, co-creator and resolver when I coach.

The gardener

I am a keen gardener and love to plant seeds. Before I do, I carefully prepare the ground and ask the questions: ‘Is it the right time to plant?’ and ‘Are the conditions ideal for growth?’ As a gardener I have to consider what is likely to nourish and encourage the growth of the seed. Is the soil fertile, are the weather and seasonal conditions good, and is the aspect right? The very best I can do is seek to lovingly nurture the growth of the seed. I cannot make the seed grow, as its actual growth is out of my hands and beyond my responsibility. No matter how much I might care and long for the seed to grow, which is my clear intention, the actual growth of the seed depends on its own resilience and inner resourcefulness and the impact and influence of wider nature.

This is an important lesson for the coach and something we need always to remember. The actual growth of your client is not your direct responsibility and is out of your hands.We can guide and help to facilitate growth but we are not responsible for our client’s actual growth.

The more we take responsibility, the less impact we can potentially make

This marks the true domain of influence of the coach.

When I coach, I do plant seeds and will openly say in my coaching conversations, ‘Might I plant a seed for you to consider?’ as you have seen in the case studies. The seeds I plant when coaching set the prospect and potential for the client to develop. Planting a seed often highlights a new way of looking at something, from which the client can learn and develop. If the client understands and learns from the value of this reframe, then the seed begins to grow.

Let me give you an example from a previous case study in Chapter 3. Susan, as you may recall, is an experienced coach who is struggling with an issue around the concepts of ‘doing’ and ‘being’. She loves the activity of doing. It is an integral part of her life. She has never felt able to work with the concept of being because she believes that to do so she would have to slow down and stop doing – which is something she feels she couldn’t do. I realise how doing and being have been split, and so I plant a seed.

I am not giving Susan the answer here, I am providing a reframe in which she can potentially learn and grow. The reframe gives her an opportunity to extend her awareness and understand beyond her current belief system. When planted, this seed continued to grow over the following month. Susan returned to the next coaching session having acknowledged her being in her doing and was applying this learning to her coaching practice. The seed was planted and, in this case, it grew quickly.

The seed does not always grow so quickly. If the seed does not grow it is not for you to worry – all we can do when we coach is decide the right time and conditions to plant the seed and nourish it to the best of our ability. It is important the coach does not feel responsible for the client’s growth. All we can do is plant seeds. Some may fall on stony ground. Let me share a short story that I read in a newspaper some years ago that I hope you will carry with you when you coach.

A team of gardeners from Kew, one of the main horticultural centres in the UK, were researching rare seeds. They had, according to the report, found such a seed within a burial ground and cave. They collected this seed and began to explore if they could nurture its germination and growth. With care and patience they did just that, and the seed began to germinate and grow. The seed that germinated was in fact 1,500 years old!

I find this a remarkable story and valuable to the coach. The seeds we plant may not germinate and grow immediately. They may remain latent until the conditions for growth are more ideal. The best you can do as a coach and gardener is to plant your seed well, with care, thought and intentionality: the rest is truly out of our hands. Conscious growth is a desire that the client chooses to fulfil. It cannot be forced; if it is, the potential for growth is immediately lost.

The co-creator

The work of the gardener and the co-creator are quite closely related. Both offer valuable insights to the role of the coach. The gardener does not garden alone – growth involves the seed, the gardener and wider nature. Growth is quite an intimate and relational affair.

In Spain, my farmhouse is surrounded by cork oak forest. These trees are ancient, and some are many hundreds of years old. Every year they drop their acorns. Often I will pick up an acorn and wonder, how in heaven’s name does the acorn become an oak tree? How are our journeys encoded in something so small, and can yet create the beauty of something so large? Such questions mark the curiosity of the coach interested in the process of creativity and creation.

Are we like the acorn and dream of becoming an oak? Maybe we all long to be, and to become, something more. The self, as we have explored, is not fixed but an emerging concept. It is the work of the coach to create chances for the clients to move closer towards becoming the individuals they were born to be. Through the coaching relationship a client can discover, and in fact create, this person. The coach, culture and wider nature are all potential architects who can potentially help to affirm, define, discover and create identity, so we are co-creators.

Through the work of the coach we evoke and give form and expression to our deepest humanity – the universal and original being

Might this be the seed of our longing and the fruition of our journey, and indeed the masterful coach? When I coach I often remember the importance of co-creation and the chance this offers my clients for self-discovery.

The resolver

When I coach I also often remember the importance of my role as a resolver. Let’s explore how and why this role is particularly important to the coach and how this capacity develops together with the opening of the creative eye.

The analytical eye is keen to answer, the appreciative eye is curious to question, and the creative eye is simply free to respond. The creative eye can expand and question, contract and answer, and also simply contemplate the unanswered question. Let me explain and illustrate the importance of this a little more fully, for this enables the coach to truly resolve.

The vision of the creative eye is able to see and witness conflict – essentially how the analytical eye makes judgements and divides and splits. Rather than being drawn into the conflict of choosing one side or the other, the creative eye is able to consider both sides equally. This is the unconditional eye of the negotiator, it can see and accept both sides without being drawn into either. Rather than seeking to immediately solve, it looks beneath to discover the unanswered question. This unanswered question is to be found at the heart of conflict and division and has the potential to offer new insight and growth and a deeper, more creative resolution.

Another way of seeing this is that the creative eye is comfortable with paradox and dilemma. It is comfortable with its own paradoxical nature and can acknowledge the paradox of things. It is not tempted to reductively simplify or solve; it is able simply to observe, contemplate and reflect.

The example I gave earlier in the role of the gardener with Susan also offers insight into the role of the coach as a resolver. Susan was caught into believing that she had to choose either this or that. In essence, I am good at doing but can’t do being, because I love activity. The creative eye can weigh the value of both equally and provide the reframe. Rather than either being or doing, I explored whether Susan could discover her being in every moment of her activity – that is, in her doing. In this way the creative eye and its instrumentation provide the coach with the balance, patience and unconditional care to discover the unanswered question that sits beneath the conflict.

In discovering the masterful coach rather than seeking to reductively solve and simplify, we can sensitively explore a deeper and potentially more creative resolution.

Rather than seek an answer, the masterful coach seeks the unanswered question

Einstein once stated in essence that you can’t solve the problem by the same logic that created it. The coach as a resolver knows this to be true and is able to guide the client to look beyond the immediacy of the presented conflict to explore if there is a deeper resolution. When I coach and find myself facing conflict, I remember the role of the resolver and begin to weigh both sides, patiently looking deeper for the yet unanswered question and the chance of a more creative and peaceful resolution.

• The many roles of the coach •

Though we often speak of the role of the coach as if it were singular, we have explored how it has an innate plurality, as illustrated in Figure 17, below.

Figure 17

As we open different eyes, discover our inner instrumentation and adopt different identities – ultimately discovering the masterful coach – the roles of the coach evolve and emerge, giving us an insight into the true scope of our occupation. The next time you coach, keep a watchful eye on how many different roles you take on in each coaching session and those that predominate in your own practice. As we discover the imagination of the masterful coach, we continue to shape and evolve the role of the coach and the scope and field of coaching.